Chapter 3

Child’s Pose

“Well, good night,” Melanie said, pausing at the bedroom door after she’d finished brushing her teeth. Her husband, Joe, was already in bed.

“Good night,” he said, leaning over to turn out the light. “And good luck.”

At first, it had seemed funny, this thing that they said to each other every night before one of them went to sleep in their bed and the other went into the living room to bounce, cajole, sing, hum, and chant their newborn baby into a maddeningly brief few hours of sleep. In the beginning, this arrangement had seemed manageable, but now that Joe was back to work, he only did a few shifts a week. Most nights it was Melanie, who was still on maternity leave. And “the beginning” was starting to seem like a long time ago. The baby was almost three months old, which meant it had been almost three months since Melanie and Joe had slept in the same bed. But this was what it took to keep the baby happy and, more importantly, quiet.

Melanie and Joe lived in an apartment building, with neighbors on every side. In the first two weeks of the baby’s life, they made daily batches of “Sorry about the Crying!” cookies. Everyone had been pretty nice about it, but Melanie had lived in apartment buildings most of her life, and she knew that the sound of a crying baby could get very annoying, very fast. So it was important that the baby, once it was nighttime, not cry. This wasn’t easy. This baby was a real crier. What they’d discovered, about a week after they’d come home from the hospital, was that the only way he’d sleep was when he was actually on someone’s body. In the beginning this was okay. Her husband was off work for a week, and then Melanie’s mom came for a few days. They all traded off, and that was nice. It worked. But that was a long time ago now. Her mom had gone home, and her husband had been back at work for months. And this was what they’d figured out: Melanie would sleep on the couch, with the baby in a Bjorn.

They’d tried everything. And this was what worked: she fed the baby in very small doses, always burped him, and never put him horizontal for the first half hour after a feeding. The doctor had suggested a swing, but he hadn’t liked it, and they really had too small of an apartment to use something that took up that much space. After a week they’d put it on Craigslist.

“Babies cry,” said her mother-in-law, who had raised her own babies on a farm in upstate New York, with only the horses and chickens to bother. “You can’t let it upset you so much.”

But it did upset Melanie, and not just because of the neighbors. She wanted some quiet too. She wanted to stop living this way. She wanted—and was this too much to ask?—to just sleep, for one night, next to her husband in her own bed.

Yoga teaches us to cure what need not be endured and endure what cannot be cured.

—B. K. S. Iyengar

Are you doing something that is starting to feel crazy and unsustainable? It could be nursing a baby every two hours around the clock or driving around town to get your baby to fall asleep, only to have her wake up as soon as you bring her into the house. Or maybe you’ve given up on bringing her into the house, so, like Audrey and Jeremy in “The Letdown,” you’re having sex in the car, because it’s the only place the baby will stay asleep—that is, if you’re having sex at all. And maybe, right about now, it feels like things are never going to change, like you’ll be driving and soothing and swaddling this tiny baby forever. But you won’t. Right about now it’s so important to remind yourself that it’s temporary.

Alison studied anthropology in graduate school and decided she would soothe her third baby the way hunter-gatherers did: by keeping him in physical contact with her all the time. What she’d forgotten was that those hunter-gatherers she’d once studied live communally, with lots of “alloparents”: relatives, friends, and neighbors who share in the care of the young. No mother is isolated and in constant physical contact with her child. Not surprisingly, Alison’s cross-cultural approach to infant care was exhausting. And, also not surprisingly, her son became accustomed to on-demand night nursings that lasted more than a year.

Accumulated sleep deprivation and crying are the hallmarks of the third month of motherhood. We exhaust ourselves trying to get a baby to stop crying and go to sleep. When our baby cries, alarms go off. Our vigilant new-mother brain believes there is something wrong with our baby and—especially when we can’t get the crying to stop—wrong with us. This is not entirely rational.

And you know what else isn’t exactly rational? The immense love we feel for a small being who cries long and often and sleeps only in spurts, bringing us to our knees and disabling that part of our brain that can think clearly and creatively.

Even in the case of the easiest of babies, there are moments when you’ve tried everything and your baby is still crying, and you realize there is nothing more you can do. And for many mothers, that time comes around quite often, especially in the third month of babyhood.

You Can’t Take the Credit for a Happy Baby …

Some babies cry more and sleep less than others. And there are some who cry less and sleep more. We’re here to tell you that neither scenario has much to do with what sort of mother you are. We’d love to say that you can take credit for a cheerful baby, but you can’t. Gratitude and humility are the only honest paths for the mothers of good sleepers. You might think it’s the swaddling or that special way of rocking him, but most likely it’s just his temperament. It’s just who he is. And it will change! Fussy babies become self-soothing toddlers. And, by the same token, easygoing babies become irritable preschoolers. It’s just the way of human development. Everything—the good and the bad—is temporary. It’s essential to take on this reality, to internalize it, and to make it your own. It’s essential to know that the baby in your arms is every bit as dynamic and evolving as you are, and that the two of you are in motion, that this moment is only a moment. This moment is temporary. There’s another one—an entirely different one—on the horizon.

We live in a culture that holds mothers responsible for a baby’s behavior and habits, when in truth, a baby affects a mother just as profoundly as a mother influences her baby, if not more so. A baby with an easy temperament is very rewarding to care for. They settle easily and quickly and are more predictable with eating, sleeping, and pooping. They can leave a mother feeling pretty good, feeling capable. They can make a new mother think, I’ve got this. And the more often a mother feels this way, the more confident she becomes. It’s a positive feedback loop. And it’s a feedback loop that a mother’s brain is wired for. Postpartum brain changes have made you more vigilant and sensitive to your baby’s cries, more intent in your desire to care for her. And those brain changes also make you feel deeply rewarded by being able to quiet and soothe your infant. Over time, this positive feedback leads to a sense of accomplishment, of a growing mastery.

… And You Can’t Take the Blame for a Fussy One

Mothers of babies who are harder (or impossible) to soothe don’t get that same brain feedback, that sense of deep accomplishment, even if they are working just as hard (or harder!) than mothers whose babies are easily calmed. Instead, they feel unraveled, exhausted, and lonely. They feel like failures.

If your baby is one of the many babies who cry a lot, you are not a failure.

Let’s say it again: you are not a failure.

If you can let this sink in, it can begin to set you free. Free from embarrassment, guilt, and isolation. It can set you free you from rushing around ceaselessly searching for reasons why your baby cries more than other babies. Searching for what you are doing wrong.

We know how hard it can be to accept the fact that you aren’t doing anything wrong. It’s so hard to let ourselves off the hook and to admit that we might not be able to do much about the crying. And then there’s that new-mother brain to contend with, the one that is built to crave the reward feelings we get when we quiet a baby. If your baby isn’t so responsive to your marvelously attentive, creative, and loving care, then your brain isn’t doing much in the confidence-building department. When you think about it, it seems terribly unfair.

And then, as if all that isn’t enough, there’s grief, too. The grief over what your baby’s infancy, that once-in-a-lifetime experience, maybe just isn’t going to be.

Erin’s first baby was a real crier. We mean a real crier. Hours and hours of crying. She and her wife tried everything: car naps, hours of bouncing her on a yoga ball, putting her car seat on top of the dryer, wearing her in a sling, in a Bjorn, in an Ergo. Erin danced; her wife did deep knee bends. Nothing really worked. All the hours of crying were hard. But the hardest part was that Erin had to let go of the idea she had about what motherhood would be for her. She wanted—all she wanted—was to push her baby in a stroller into a coffee shop, order a coffee, and sit and drink the coffee while her baby slept in the stroller. She didn’t need to do it every day, or even that often. She just wanted to do it once. But her baby was not a sit-in-the-stroller kind of a baby. For months she mourned that cup of coffee. And, mourning that cup of coffee, she was really mourning the ideas she had about what kind of mother she would be.

One of the many complicated things about early motherhood—these months when you are existing in the world as a very different person (and also very much the same person) as you were before your baby was born—is that the sort of mother that you are is so relative to the sort of baby you have. Or, to be more accurate, the sort of mother that you feel that you are, that you perceive yourself to be.

If you have a baby who’s not so easy to soothe, you’re up against a lot right now: your own ideas about what motherhood would be like, along with a society that’s telling you it’s time to get things “back to normal”—whatever that means. And, as if that’s not enough, you have a nervous system on high alert (mostly unnecessarily) and a brain that really, really wants you to get that baby to stop crying.

Erin has a habit (and she might not be alone in this) of driving far out of her way to avoid traffic. She doesn’t necessarily get to where she’s going any faster—and she definitely uses more gas—but it feels better than sitting in traffic. She likes to keep moving. This is often how new mothers approach time with a fussy baby. We cajole, shush, dance, nurse, and bounce, when maybe, just maybe, the baby is going to quiet and fall asleep on her own time, no matter what we do. A fussy baby who is sated and dry really might just need your company. Can you offer her that? And can you free up some of your heroic caretaking/troubleshooting/consoling energy so that you can offer it to yourself?

Can you sit in the psychic traffic with your crying baby so there’s some gas left in the tank for you? Can you remember that it’s temporary?

Did You Know …

Infant crying from two weeks to twelve weeks is so common that it has been dubbed the “Period of PURPLE Crying,” PURPLE being an acronym for crying that Peaks around two months and comes on Unexpectedly. Your baby is Resistant to soothing and looks to be in Pain, even though she likely is not. The crying Lasts for a long time, mostly in the Evening. All this might sound familiar to you.

There are 1.5 million search results when you Google “persistent infant crying,” but very few are about the impact crying has on mothers. Christy Clancy, in her story “Colicky Residue,” from the anthology So Glad They Told Me: Women Get Real about Motherhood, describes her experience of living through colic: “Colic is three months of root canals, jack hammers, metal music, nails on chalkboard, forks scraping against teeth, tea kettle whistles, horns honking, alarms blaring, raging seas. Colic is extreme parenting when you’re least ready for it—you’re sleep deprived, sagging, leaking, bleeding, engorged, insecure. It was an experience that penetrated every border of patience and sanity that I thought I could maintain.”

Our baby’s cries are designed to get us to respond, and respond we do! Because we don’t often know why our babies are crying, we exhaust ourselves trying everything to soothe and quiet them. And when we can’t find a way to soothe them, we’re sure there is something wrong—with them, or us. And if we are one of the one in five mothers with a baby who cries for hours a day, every day, for weeks on end, we are sure the world will judge us as a bad mother. Or dole out unsolicited advice.

One of the few interview studies of mothers with so-called colicky babies showed that pediatricians often told them it wouldn’t last forever and showed them the door, yet everyone on the street and in restaurants and grocery stores had admonitions and advice. These mothers ended up hiding from all this advice and judgment, further exacerbating the situation by making them isolated and lonely. All they wanted was support and empathy, not advice. They felt they had lost something precious: the quiet baby they had for the first week after birth, the still-sleepy baby who slept and fed, then slept again. And equally as precious, they felt they’d lost the mother they’d thought they’d be.

Crying Baby Tonglen

When a break from a crying baby just isn’t possible, crying baby tonglen is a practice that works on the spot to help you feel better, something that can sidestep the brain’s desire for that feeling of reward and accomplishment, something that helps your nervous system to rest a little, to move your consciousness outside its ardent yet arbitrary ideas of failure and success and into the present moment.

Crying baby tonglen is adapted from the ancient Tibetan practice of tonglen, which means “receiving and sending.” Because it’s a breathing practice, it can help you get out of your rushing mind and into your body. Because your instinct is to flee or get the crying to stop, at first it might feel strange to just be with the exhaustion and crying.

As you inhale slowly, allow the situation to be what it is. Acknowledge it all: the crying, the exhaustion, the disappointment, and the annoyance. Breathe it all in. Soften the front of your body. As you exhale, send compassion to you and your baby. Imagine, as if from a small distance, the two of you doing the best you can under the circumstances, knowing that it’s temporary.

Repeat this two more times.

As you repeat the practice, visualize all the other mothers in the world who are caring for a crying baby and send them some compassion too. You are not alone.

One Minute Yoga 3

GRACE 3

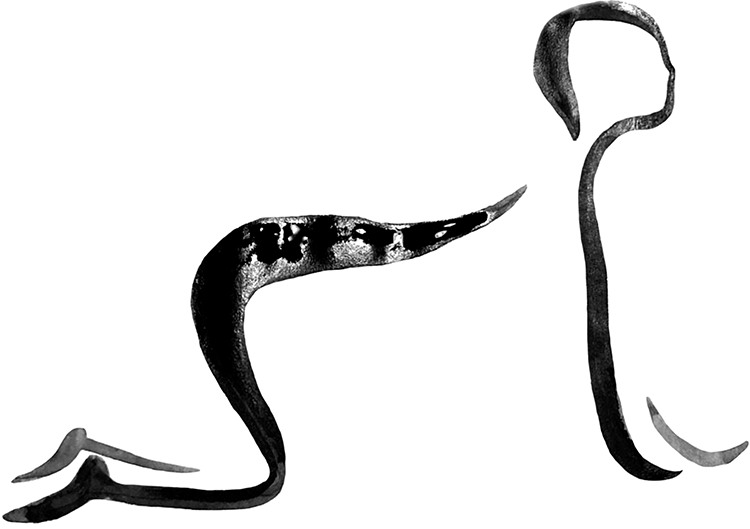

- Gather yourself in child’s pose (shown below) or sitting or lying down. Bring your awareness inward to the sensation of ground, feel yourself connecting to the steadiness of it.

- Rest by rolling your shoulders in circles three times in each direction, shake out arms and hands, then just let them sink down while you breathe slower and deeper.

- Ask “How am I right now?”

- Compassion can take many forms. This month, ask for what you need. Protect yourself from unnecessary obligations.

- Engage in your day, knowing that this is temporary. Begin again.

Breathing 3

Continue with tonglen.

Use the three-part breath while breathing in any discomfort or anxiety, breathing out ease and peace. Visualize yourself in a large circle of other mothers faced with challenges, all wishing you and each other ease, peace, and happiness.

Asana 3

If you are a mother whose baby is crying most of the time, and you can’t find quiet moments, simply practice crying baby tonglen in child’s pose and slow down your movements as you care for your baby. Next month, when things are easier, you can continue with the asana practices. We are sending you a big hug.

If you do have a few minutes while your baby is asleep or happy, cat/cow warm up gives you a chance to reconnect with your body, breath, and movement—with pleasure and a sense of playfulness.

- Start in child’s pose.

- Kneel and sit back on your heels, then place hands on the floor in front of you and slowly slide them forward until your forehead is on the mat or blanket. You can keep your hands under your forehead or straighten your arms down by your sides. Feel your belly expanding and emptying against your thighs as you breathe.

- Bring yourself up onto hands and knees: hands under shoulders, knees under hips for cat/cow.

- Inhale and soften your belly as you lift the tailbone and crown of your head, gently looking upward.

- Allow your lower back to gently arch downward as your chest opens.

- On a nice long exhale, tuck the tailbone under, round your spine toward the ceiling and engage your belly button toward the spine, and lower your head.

- After a few rounds, slow the movements down a lot. Slow is nourishing, slow feels good.

- Move your hips and shoulders very slowly in any way that feels good right now. Play around with your breath, stretch, yawn, and sigh.

- Come back into child’s pose and notice how you feel. Before returning to engage with your life, take a moment to repeat this mantra: “It’s temporary.”

This practice is a way to begin experimenting with slowing down. When you start thinking about your baby’s crying as something that isn’t your fault, something you can’t always fix, you can work on slowing down. And if you can’t slow your mind down right away, try consciously slowing down your body, noticing what it feels like to rush. Ask yourself: What am I rushing toward? Try moving more slowly. Change a diaper half as fast; wash your face slowly. Walk—don’t run—back into the house when you forget your keys. And then notice how it makes you feel.

Maybe you’ve heard of the slow food movement, so how about slow motherhood?