Chapter 4

Finding Your Feet

It was Carly who suggested the three of them get together. “Just like old times!” she’d said in her group text.

Funny to think that just four months ago was old times, but considering how much had changed, it did feel like old times. Four months ago they were The Bumps, three coworkers who’d found out they were pregnant at the same time. Amber was the sickest of all in her first trimester and couldn’t even walk into the office break room without throwing up. So, in solidarity, they all ate their lunches outside on a picnic table behind the building. It was true solidarity, considering it was December. They felt so lucky to have each other. They spent their lunches talking about everything (how often they peed, what smelled good, what smelled terrible) and asking each other all the questions: Are you going to circumcise if it’s a boy? Do you think you’ll co-sleep? Or nurse?

But then, after the babies were born, after the congratulatory “OMG! She’s beautiful!” texts, they lost touch.

Work was suddenly so distant for all of them. They worked at a women’s health nonprofit, where the benefits were good (in part because the pay was not), including six full months of maternity leave. They’d been busy with visits from parents and in-laws, baby-and-me exercise classes, and so on. They just hadn’t seen each other.

But then came Carly’s text: “Hey! We need to give this group a new name! Suggestions?”

Noelle was the first to text back. “How about The Lumps?”

That got everyone going, with lots of crying-laughing emojis and “I’ve missed you all!” and “OMG, do we need to talk!”

And so they made a date. The weather was still warm, and they decided that, in honor of their first-trimester alfresco lunches, they’d meet outside, at a park near their old office.

Carly arrived first, lay down a blanket, and plopped her baby, a round and cheerful girl, down on it.

Then Amber came, a baby boy strapped to her chest in a wrap. She threw her arms about Carly, and the baby promptly started to cry. “And here we go,” Amber said. “This kid has two speeds: crying and about to start crying.”

“You’re heeeerrrre!”

Carly and Amber turned to see Noelle running toward them—actually running—with a jogging stroller.

Carly and Amber waved, and Carly leaned over to Amber. “I thought you weren’t supposed to put a baby in one of those yet,” she whispered. “Isn’t it six months?”

“I have no idea,” Amber whispered back. “I can’t even get this boy to sit in a car seat without shrieking. At the rate I’m going, I’ll be taking him to kindergarten in this thing.” Amber was trying to sound laid back, but the truth was she was pretty close to losing her mind about how much her baby cried and how sad she was that she couldn’t just put him in a jogging stroller and take off for a run. Or even a walk. Anything, as long as the baby was quiet.

“This is such a treat!” Noelle said, then took a long swig from her water bottle.

Oh, water! thought Carly. Damn, I knew I’d forgotten something. Why was it still so impossible to get out of the house with everything she needed?

Wow, Noelle looks really good, thought Amber. You’ve really got to start exercising, she told herself. Last month she’d downloaded a whole slew of “Mommy and Me” workouts and told herself she’d do one every morning, but she hadn’t even done one. The most exercise she got was from bouncing the baby up and down on a yoga ball to get him to go to sleep.

“Sit, sit!” Carly said. “Let’s see these babies!” They all sat down on the blanket. “Wow,” Carly said, watching as Amber put her baby down on his stomach only for him to roll right over onto his back, then onto his stomach again. “That’s amazing.” Just this morning Carly had cried to her mom on the phone because her baby wasn’t rolling over yet. Now she was sure there was something really, really wrong with her.

“I think she’s hungry,” said Carly, scooping up her baby, afraid that one of the moms would comment on her inability to roll over. She lifted her shirt, and the baby started to nurse. The sight of Carly nursing made Noelle panic. After mastitis in both breasts and a week of thrush, she’d stopped nursing, and she felt terrible about it. And she also felt terrible, honestly, about how completely relieved she’d been. But she didn’t want her friends to know.

“So, Bumps,” Amber said, trying to sound cheerful, “how’s it going?”

“Great!” Noelle and Carly lied, in unison.

Don’t surrender all your joy for an idea you used to have about yourself that isn’t true anymore.

—Cheryl Strayed

The fourth trimester has come to a close. Your baby is still small, and your experience of motherhood is still new, but you are both different beings than you were in those early days after birth. You’ve figured out a few things. Your baby is more alert, more human.

This is a good time to talk about this idea of “getting your life back.” It’s a fraught concept and, we think, a misleading one. So much of the talk of life with a baby after the first three months is about what you can get back. What you can return to or regain. But birth and early motherhood alter us in such profound ways that we think it’s helpful to focus less on returning and more on moving forward. This isn’t to say that we don’t understand (or remember oh so well) the idea of wanting to get back our bodies, our minds, our good night’s sleep. We do! It’s just that birth and babies change everything, and in the face of that fact, we think it can be more satisfying, self-affirming, and—honestly—more fun to think about moving your body, mind, relationships, sleep patterns, and everything else forward. Forward into a new world, a new life, and new ideas about yourself and what you are capable of, what you need, and what really matters to you.

Of course, it can be just as important to connect with people and experiences from life before baby that are grounding. A silly (but important) example: When Erin’s first baby was three months old, she threw out her sensible black diaper bag and replaced it with an impractical hot-pink leather handbag because it made her feel like herself again. The straps didn’t fit over her shoulder, the bag had no good pockets, and she could never find anything in it, but that bag brought her back to herself. That bag made her happy.

So perhaps what we’re trying to say here is that this transition is a time of moving forward as well as bringing your most beloved parts of yourself from before birth forward with you, instead of trying to get your new reality to move “back” to before.

When You Feel Ready

In keeping with this idea of moving forward into the fifth trimester, our yoga practice this month will be a transition from floor to standing. Transitions bring feelings of uncertainty, loss, and excitement. They also lead to transformation.

In yoga, a teacher often moves the class into a new posture by saying, “And when you feel ready …” When you feel ready is an important cue in yoga and in life as a mother. The transitions of the fifth trimester—transitions to work, to more time away from your baby, to new sleeping arrangements—all start when you feel ready, not because you have now reached a particular postpartum month. You might want to stay where you are for a while longer; you might even need to take a step back. And if you do, know that it’s perfectly fine to scale back and rest if you’ve taken on more than you have energy for. In a yoga class, you can always move out of a straining pose right into child’s pose, and you can stay there as long as you need to. The same goes for life with a baby. You can adapt schedules, routines, or anything that’s putting too much of a strain on you right now. You can step back from trying to nurse your baby while taking a work call or squeezing a trip to the grocery store between two naps. If your transition is too much right now, if you need more time, remember that child’s pose, however you might define it, is always waiting.

Of course, it’s also possible that you were ready and eager to get back to work, activity, socializing, travel, and the adult world in general long before this time. Regardless of where you’re at, we think it’s fairly likely you feel some ambivalence. Which is why we think this is a good time to slow down, take a closer look at these transitions, and think about how you might want to move through them. Like transitions in our yoga practice, transitions in life go better if we move slowly, break it down, and tune in to the way we feel from the inside out.

You are moving out of what Alison likes to call the “mother-baby couple bubble” phase. Your attention is naturally beginning to turn outward as you take on more responsibilities and face new decisions about work, friends, and activities.

Step Away from the Instagram

It’s normal at this pivotal point to be asking, Who am I now? And in trying to answer that question, it’s tempting to create unrealistic expectations for you and your baby. These expectations are often fueled by comparisons with other mothers, both in person and on social media. When we compare our private self to someone else’s public self, we get a distorted comparison. Be especially wary of comparing yourself to anyone who is trying to manage the impression they are making. And, quite honestly, that’s every mother—celebrity moms, Instagram moms, the moms in your baby group, your sister-in-law who had a baby a few weeks before you did. New mothers are uncertain and vulnerable, and the world is filled with judgment toward them. So of course new moms are trying to manage the impression they’re making, trying to present a cohesive, capable self and a happy, content baby.

Which is what makes these comparisons especially harmful. As a friend of Erin’s once said, “The comparison game is the only game we play to lose.” And it’s true—we often seek images or ideas of motherhood that end up making us feel badly about ourselves.

A more gentle, nurturing way to compare your private mother self to another private self is to read literature about motherhood, written by mothers, like Operating Instructions by Anne Lamott and Things I Don’t Want to Know by Deborah Levy. Such books can give us a sense of connection and empathy with these authors, and they can also illuminate parts of our experience that perhaps we weren’t aware of.

Another way to feel connection is to be brave enough to share your own imperfections and vulnerability, to take a break from managing the impression you’re putting forward. In one of Alison’s workshops, a mother answered the question “What brought you here?” with a story of a recent morning at her home. She was in the kitchen, with her toddler on her hip, when her phone rang. She went to grab the phone, and her toddler’s foot knocked a dozen eggs onto the floor. She yelled something really satisfying yet crude, and the dog came rushing in the open door and slid into home base through the eggs. Starting to cry and laugh, she peed in her pants. This, she said, was the reason she had come to the workshop. She thought she could use some yoga.

One by one, through tears and laughter, every mother told the real story of her life, not the Instagram version, not the good impression. Sitting in that circle, with the truth shared and exposed to light, there was a collective sigh of relief. This was the first time some of these mothers had felt safe sharing the stories of their inner lives. Many mother-and-baby groups had felt more like a competition to these women, leaving them more isolated than ever. That one brave mother gave the rest of the group permission to relax and open up. And in that moment, all of the mothers felt connected and realized that they weren’t alone and weren’t the only ones feeling isolated, insecure, and overwhelmed.

Every Mother Needs a Friend Like Alison (Says Erin)

Our third suggestion is perhaps our favorite: befriend an older mother, someone whose children are grown or at least much older than yours. We know it isn’t easy to find a friend outside your demographic, but book groups, yoga classes, and spiritual communities can all be places to start. Erin and Alison’s friendship (which began when Alison joined a Peace and Justice study group with Erin’s then girlfriend, now wife) was a source of comfort, wisdom, and much hilarity for Erin in her early days of motherhood, and it continues to be that fifteen years later. When Alison came over to meet Erin’s baby for the first time, the baby was sleeping, and Erin couldn’t stop looking at the clock. “She needs to eat in five minutes,” Erin said. “I need to wake her up.” Alison peered over the side of the bassinette at the sleeping baby. “She looks pretty happy right now,” she said. “How about you just eat some of that cake I brought, and we wait for her to wake up?”

Every mother needs a friend like Alison, someone who can tell you not to wake your sleeping baby and also regale you with stories about the time she and her husband took their three-month-old to an island in Maine, and she rinsed her cloth diapers by hand and then boiled them. (True story! Alison boiled cloth diapers! Then hung them on a clothesline that she’d strung herself between two trees!) And together you can laugh; you can laugh so hard about boiling diapers in pursuit of perfect motherhood. Because if a friend your own age told you that same story, well, you might have a lot of feelings about her and her diapers, and she might have a lot of feelings about her and her diapers: jealousy, inadequacy, judgment, annoyance, and defensiveness, just to name a few. But when a woman a generation (or two) beyond tells a story of too-earnest maternal striving, you can laugh. And laughter is one of the most powerful forces we have to create the momentum we need to move forward into a meaningful and enjoyable life with a baby.

More specifically, your life with your baby. In your time.

Motherhood Is a Relationship

When we compare ourselves to others, we are looking away from ourselves and our babies. One of the keys to that sense of meaning and enjoyment we want to be moving toward in the fifth trimester is to think differently about what, exactly, motherhood is, and to claim your own motherhood experience. At this particular transition time, it’s helpful to move away from the idea of motherhood as an identity toward the idea of motherhood as a relationship. A rich, unique relationship between you and your baby, one that will continue to evolve as your child grows. And one that will move at your own pace, in your own time.

In earlier chapters, you started to become familiar with ways to calm and soothe your nervous system with your breath and self-compassion. Now we can go one step beyond those calming practices to a practice of gentle awareness and curiosity about yourself and your baby.

Start by gently observing your baby as she is now. It’s always easier to observe someone other than yourself at first. How much stimulation does your baby like? Does she like being outdoors or around lots of people, or does she prefer the quiet of home? Does she need routines, or is she adaptable to change? Does she feed quickly and efficiently or does she like to take her time, interacting with you? How does she do with other caregivers?

Now turn your attention to yourself, using the same nonjudgmental approach. Are you craving company, or does company wear you out? Are you aching to take on a project, or would a bath feel better? Are there moments when you feel content, capable, and expansive, and others when you feel confused, overwhelmed, and contracted? The more you can observe the ways in which you are responding to the demands of your relationship with your baby, the easier it will be to sort out what feels good and important, and what is causing you anxiety or creating a sense of dissonance. You can notice what gets you up and moving and what settles and grounds you. The more you listen to these messages within, the less distracted you will be by unrealistic expectations and comparisons.

Mothers Are Our Heroes, but They Are Not Superheroes

One Halloween, many years ago, a sweet little boy we knew dressed up as Superman. He’d been looking forward to the day for months, and his mother had made him a wonderful costume. On Halloween night he put it on, looked in the mirror, and was crestfallen. “What’s wrong?” his mother asked. “I thought I was going to be Superman,” he said, tears in his eyes, “but I’m just a jerk in a cape.”

No matter how old we are, sometimes it can feel like there’s an unbridgeable gap between who we are and who we think we should be. This sense that we aren’t enough leaves us anxious and disappointed. Often the expectations we have for ourselves and our babies far exceed what is realistic. This can be a good time to ask: What sort of superhero abilities do I expect of myself? To always meet my baby’s needs? To be at ease in the face of motherhood’s twin states of profound responsibility and deadening monotony? To be entirely confident in my baby’s attachment to me, never worried or anxious about the hours she spends in the care of others? And then, when you fail to perform at superhero levels, do you feel like a jerk in a cape? You’re not! You’re a mother trying to reconcile deeply held expectations with an unexpected new reality. This is one of the reasons so many new mothers feel anxious. When who you are and what you think you should be are pretty much the same thing, there’s peace. There’s contentment. But in the early months of motherhood, expectation and reality can exist on opposite sides of a canyon. The first step to narrowing that divide comes with shifting your gaze away from others and toward yourself and your baby. It comes with a close and affectionate look at your feelings.

Feelings Are Great Messengers

We can tune into sensations in the body that are associated with feelings. We can notice the stories we tell ourselves and the feelings they evoke. You may notice a whole new menu of feelings since becoming a mother. Feelings are pretty fleeting, but often without even knowing it, we are working overtime to avoid or resist certain feelings, especially boredom, anger, and anxiety. What would happen if you just allowed for anxiety from time to time? Or we might be chasing other feelings, like pleasure or connection. The more aware we are of the feelings that motivate us, the more freedom we have to choose our responses to those feelings. Read over the list of feelings below and notice what your response is to each one.

- acceptance

- anger

- anxiety

- boredom

- confidence

- connection

- contentment

- courage

- curiosity

- disappointment

- embarrassment

- empathy

- enthusiasm

- fear

- frustration

- generosity

- gratitude

- grief

- guilt

- jealousy

- joy

- loneliness

- love

- regret

- resilience

- sorrow

- vulnerability

Now, in real, moment-to-moment life, especially life with a baby, we experience many emotions at once, and they are often contradictory. As you most likely already know, it’s possible to feel both terribly bored and completely enamored with your baby. In chapter 5, we’ll talk about the intense ambivalence inherent in all mother-baby relationships and how to keep moving forward in the face of conflicting and confusing emotions. But first, it’s important to practice simply identifying those oft-conflicting feelings, a practice that will gently but firmly require you to shift your attention away from the compelling distraction of other mothers, both on social media and in real life, and focus on yourself and your baby. Your attentive, noticing mind can’t be in two places at once. Let us clarify that: your noticing mind can try to be in an endless number of places at once, but it can only succeed at being in one place at a time. And right now that place needs to be your own heart.

Because your motherhood is about you. You and your baby. In your own time.

Did You Know …

Accepting ambivalence can set you free. And it can free up energy that would otherwise go into denying feelings. We live in a world where ambivalence about motherhood is prohibited. Mother’s voices of regret are silenced. It is perfectly normal to feel ambivalent about everything from the pain of childbirth to breastfeeding to the constant and unrelenting demands of baby care. The less support we have, the more ambivalence we are likely to feel. When we don’t have adequate help, we have fewer resources to go around, and competition for our time and energy is more intense. Imagine how your feelings about breastfeeding would change if you had another person to do all the cooking and housework for you? Most of us, sadly, don’t have that kind of help, so we are usually exhausted and conflicted while loving our baby more than we could have imagined.

If we can accept ambivalent feelings as a normal part of motherhood, not something to be overcome, hidden, or denied, we can free ourselves. We free ourselves to simply feel what we feel. And then let it pass. It is normal. So you might want to come to your feet and move out into the world, and at the same time, you might want to just lie on the bed and stare at the miracle that is your baby. The more you allow yourself to feel both of these emotions compassionately, without fighting either, the sooner an impulse in one direction or the other will surface. In your own time.

One Minute Yoga 4

GRACE 4

In child’s pose:

- Gather your attention and energy inward in child’s pose, by feeling your shins and hands on the floor and your belly on your thighs.

- Rest and relax your shoulders, jaw, and belly as you breathe three slow, deep breaths.

- Ask “How do I feel right now?” “Where do I feel it in my body?” “What emotions am I feeling now?” “What emotions am I avoiding, wishing for?”

- Compassion is the ability to listen to the answers with curiosity, without judgment, the way you would listen to a dear friend.

- Engage with your life with more ease, curiosity, and acceptance. Begin again.

Breathing 4

In child’s pose or while moving, focus your attention on your inhale, without speeding it up or deepening it unless you want to. Feel fresh new oxygen filling your lungs. Allow the exhale to just happen. Repeat for three breaths.

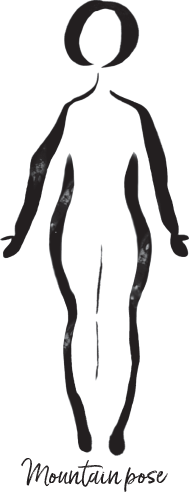

Asana 4

- Come into child’s pose.

- Take three slow, deep breaths, focusing more on the inhale, and allowing the exhale to just happen.

- If you're feeling ready to come to standing, then, on the next inhale, lift your hips to the sky into downward-facing dog. Bend your knees and lengthen your spine. Take three long, slow breaths in downward-facing dog. Let your heels drop a little toward the mat or peddle your feet gently.

- Walk your feet slowly toward your hands, knees bent, foreword fold, sway side to side for one or two breaths.

- On the next inhale, bring your hands to your thighs, flatten your back, engage your core and hinge from your waist like a clamshell, coming up to standing. Exhale. Take a long, deep breath and let your shoulders soften down. Feel your body standing up. Notice whatever you are feeling from your feet to your crown.