2

Home Caregiving

At one time or another, most families need to provide home care for a family member who is ill, aging, disabled, or recovering from surgery. Caring for a person at home can improve his or her sense of well-being, which can lead to a quicker, more complete recovery.

Preparing for Home Care

Home caregiving requires a well-thought-out care plan, which must be flexible enough to meet the continually changing needs of the person who is being cared for. Discussing expectations and potential problems in advance with all members of the caregiving team—such as doctors, nurses, therapists, social workers, and family members—will help you to develop a support network and the best care plan possible. The members of the caregiving team will consider the following factors when developing the care plan:

• How long the illness is expected to last

• How the person’s condition might improve or worsen

• Whether it is possible for the person to fully recover

• Whether rehabilitation therapies—such as physical, occupational, or speech therapy—will be needed to promote recovery, and who will provide these services

• The specific medical emergencies that might occur and how these emergencies should be handled

• Caregiving adjustments you will need to make

Setting Priorities and Goals

The best time to begin planning the transition from hospital care to home care is shortly after a person has been admitted to the hospital. A hospital social worker, primary care nurse, or case manager can guide you through this transition and help you plan successful home care strategies so you can concentrate on providing the best possible care for a person, once he or she leaves the hospital. Consider the following questions when developing your care plan:

• What types of care are needed, and what is the best way to provide them? Can you provide this care at home?

• Will the person require 24-hour care?

• If you need to monitor health indicators such as blood pressure or blood glucose levels, or administer and adjust medications, who will train you to perform these tasks? Who can you call for advice and help?

• Who will be part of your caregiving team, and what roles will they play? You may need the services of a variety of people, such as doctors, specialists, visiting nurses, therapists, and home health aides.

• What type of care is available, and from which agencies? Is the care effective and dependable, and what are the costs?

• Will you need any special equipment, such as that used to provide oxygen or intravenous feeding? Who will train you to operate it, what type of maintenance does it require, and who will provide the maintenance?

• Will physical changes have to be made to the person’s home to enhance his or her mobility and safety? For example, you may need to have ramps, railings, or electric stair lifts installed on stairways, or grab bars and handrails installed in bathrooms to help make it safer to use the toilet or bathtub.

• Will the person need specialized equipment to help him or her perform daily tasks? Various useful devices, such as a handheld device called a grabber that can help a person grasp objects that otherwise would be out of reach, are available from drugstores and medical supply companies.

• Will pets in the home create any problems? Some pet-related routines and behaviors may need to be adjusted to prevent accidents. For example, you might install a child safety gate to keep a dog from getting in the way of a person who is learning to use a walker.

• What are the person’s likely transportation needs? You may be able to use your own car or van, or you may need to use a specially equipped van. Transportation services are available at reasonable cost in many communities; ask a hospital social worker for recommendations, or check your phone book.

In most families, a spouse, parents, siblings, or children provide most of the routine care, with assistance from various health care professionals and under the supervision of a doctor. To provide quality care, learn as much as you can about the person’s illness or condition:

• Talk with designated contact members of the health care team about the person’s condition. Write down questions and take notes or tape record sessions with care instructors. If you feel your questions are not being addressed in these meetings, schedule a separate meeting to resolve them.

• Consult a private clinical social worker, gerontologist (aging specialist), or other appropriate care provider. These people are trained to evaluate your family’s needs and can help you find a qualified physical therapist or household helper, as well as supplies you may need such as a hospital bed. They also can help you find a nursing home in your community that meets your loved one’s needs.

• Use the services offered by local and national support groups and organizations, community out-reach programs at nearby hospitals, and help hot lines. Consult your local public library, bookstores, and the Internet for additional information and resources.

Caregiving Skills

Once the person is home, your daily routine will focus on meeting his or her needs. In some cases, the person needs the expertise and training of a registered nurse or other professional caregiver.

But with proper training and guidance, you will learn to perform the required tasks on your own. Always call on the experience of professionals whenever you need to.

Giving Medications

Learn all you can about the person’s medications, starting with the names of the drugs. If he or she is taking several medications, keep a list of their names and a written schedule of the daily doses of each so that you can check off each dose as you give it. Get the instructions about each prescribed medication from your doctor or pharmacist, and make sure you understand them. Read the package insert that comes with each medication. You may want to ask the doctor or pharmacist the following questions:

• When should the medication be taken (with meals, first thing in the morning, at bedtime, or two or more times a day)?

• How long should the medication be taken? Will refills be necessary?

• What are the possible side effects? What should be done about them?

• Does the medication interact with any other drugs that the person is taking?

• Should the person avoid certain foods?

• Does the medication have lasting effects?

• Does the medication have any warnings?

• Does the medication come in various forms? For example, if the person has problems swallowing pills, ask if the medication is available as a liquid.

Remember that all medications must be taken exactly as prescribed by the doctor. Never stop giving medication without the doctor’s permission.

WARNING!

Allergic Reactions and Unpleasant Side Effects

Some medications can cause an allergic reaction (producing symptoms such as hives, itching, a rash, or wheezing) or side effects (such as nausea or dizziness). If the person develops any of these symptoms, call the doctor immediately to find out if you should stop giving the medication. The doctor may need to adjust the dosage or change medications.

Providing a Healthy Diet

Healthy eating is essential for maintaining the person’s health and well-being and also can promote successful recovery. If the doctor has not prescribed a special diet for the person, you can provide the foods that he or she normally eats.

Adequate fluid intake also is an important part of a healthy diet. Most people should drink at least eight glasses of fluid every day, including water, milk, juice, broth, or caffeine-free coffee, tea, or soft drinks. If the doctor limits the person’s daily fluid intake, follow the doctor’s instructions.

The following tips can make it easier for the person to consume a healthful diet. Adapt them to the person’s needs:

• Slice, dice, chop, mash, or purée foods to make them easier to chew and swallow.

• Look for ways to add calories and nutrients to the diet of a person who is at risk for weight loss. For example, fortified milk shakes can be tasty and nutritious. Ask your doctor if the person you are caring for could benefit from nutritional supplements that provide added nutrients and calories.

• People with decreased appetites may consume more calories by eating five or six smaller meals throughout the day rather than three large meals.

• Ask the person what foods he or she likes or dislikes.

• Make meals look attractive.

• Eat meals together whenever possible. Mealtime rituals can be comforting and can help restore a sense of normalcy to a person’s life.

• If a stroke has paralyzed one side of a person’s body, food may tend to collect in the paralyzed cheek. If this occurs, gently knead the cheek with your finger while the person is chewing, to help move the food along.

• If the person is able to exercise, encourage and help him or her to do so. Regular exercise stimulates the appetite and helps prevent constipation. Ask the doctor which exercises are best.

Assisting With Eating

If the person cannot feed himself or herself, you must feed him or her. Cut food into small, bite-size pieces, or purée it to make it easy to chew and swallow. Before feeding the person, be sure he or she is sitting upright in a comfortable position. Tuck a napkin or hand towel under the chin to catch any spills. Taste the food to be sure it is not too hot. Because feeding someone can be a lengthy process, keep the food warm in a warming dish.

If the person cannot chew or swallow—because of oral radiation treatments, jaw injury, or stroke, for example—you may need to provide nutrition through a feeding tube or intravenously (directly into a vein). The doctor or nurse will teach you how to do this correctly and safely. Watch closely for any signs of infection: pain, redness, or swelling at the insertion site of the intravenous needle or feeding tube, or fever.

Good oral hygiene is essential for maintaining a healthy diet. Make sure that the person practices good oral hygiene (daily brushing and flossing) and that he or she sees the dentist regularly.

Special Diets

If the person needs to follow a special diet, your doctor can recommend a nurse or registered dietitian who can teach you how to prepare the food. A registered dietitian can assess the person’s dietary needs, provide guidance, and answer any questions you may have. Common special diets include low-sodium, low-protein, and liquid diets.

Low-sodium diet

You can easily reduce the amount of sodium in a person’s diet by not adding salt to food when you cook or serve it. Avoid serving foods—such as cured or tenderized meat (including ham, bacon, and cold cuts), smoked fish or meat, cheese, pickles, canned foods other than fruit, processed and prepared foods, and salted butter or margarine—that are high in sodium. Always check package labels for the sodium content of canned, prepared, and processed foods. Buy canned foods labeled “no salt added.”

If you need to further restrict the person’s salt intake, your doctor can tell you how to cut down on or eliminate foods that contain even small amounts of sodium. To add flavor to foods without adding salt, season them with spices, herbs, or lemon juice. Ask your doctor if it is all right to use a salt substitute. Most people find that after several salt-free weeks, they do not miss the salt.

Low-protein diet

To reduce the amount of protein in the person’s diet, cut down on protein-rich foods such as eggs, meat, fish, and dairy products. Because protein supplies much of the body’s energy requirements, you will need to compensate by adding extra carbohydrates to the diet. If your loved one needs to cut back on protein, ask the doctor or dietitian for guidance.

Liquid diet

Sometimes doctors prescribe a liquid diet, in which the person cannot eat any solid food. In this case, ask the doctor to recommend a dietitian who can plan an appropriately balanced diet. You also may want to ask the doctor about giving the person liquid nutritional supplements, which are widely available in single-serving cans.

When giving liquids, always elevate the person’s head slightly to help prevent choking and spilling. The best way to do this is to hold the cup or glass while the person drinks through a flexible drinking straw. Keep the person’s head elevated for at least 20 minutes after eating to help prevent choking or regurgitation.

Meal Services

Special meal services such as Meals-On-Wheels provide home delivery of nutritionally balanced hot and cold meals for older or disabled people who are not able to prepare their own meals. Fees for this service are based on a person’s ability to pay. Because the demand for such services is high in some communities, preference may be given to people with limited income. In other communities, anyone who can pay the full fee is eligible. Special diets require a written order from a doctor.

Preventing Pressure Sores

A person who is confined to bed is at risk of developing pressure sores, especially if his or her movement is restricted or sensation impaired. Pressure sores develop on the parts of the body that bear weight or rub against bedding. They are the result of continuous pressure that interferes with blood circulation to the tissue in the surrounding area. Poor nutrition and incontinence also can contribute to the development of pressure sores.

A pressure sore begins as a patch of tender, reddened, inflamed skin. Gradually the skin turns purple, breaks down, and forms an open sore. The sore gradually grows larger and deeper, and can become infected. Pressure sores are usually very slow to heal. They will not heal at all unless pressure on the affected area is greatly reduced or eliminated.

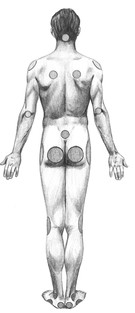

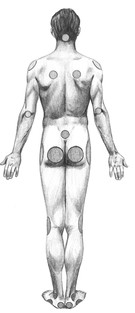

Pressure sores

The most common sites for pressure sores are the base of the skull, shoulders, shoulder blades, elbows, lower back, hips, buttocks, sides of the knees, ankles, sides of the feet, and heels.

The best way to prevent pressure sores is to change the person’s position every 2 hours during waking hours. Gently move the person from one side onto his or her back, then to the other side; rotate positions throughout the day. Never drag the person from one position to another in bed—you could damage the skin, increasing the risk of developing pressure sores.

About once every hour, have the person stimulate circulation and prevent joint stiffening by wiggling his or her toes, rotating the ankles, flexing the arms and legs, tightening and relaxing the muscles, and stretching the entire body. If the person is immobile or very weak, you can perform passive exercises by gently bending and straightening his or her joints several times a day.

Help the person out of bed as often as possible (see page 191). Moving around also will help prevent fluid from collecting in his or her lungs, a major risk factor for pneumonia. If the person cannot get out of bed, encourage him or her to move around in bed frequently.

Place cushions and pillows between the person’s knees and under his or her shoulders to help relieve pressure. Alternating pressure mattresses, synthetic sheepskin mattress pads, and heel protectors allows air to circulate around the person’s skin and helps reduce pressure and friction against the bedding. A bed or foot cradle (a tentlike device placed at the foot of the bed) helps to keep the weight of blankets and other coverings off the person’s feet. You can rent or purchase these items from drugstores and medical supply companies. Remember that, even when you use them, you still need to turn the person frequently to prevent pressure sores.

Keep the person’s skin clean and dry, especially in areas most vulnerable to pressure sores. Bathe the person frequently (see right). Ask the doctor or nurse to recommend an alcohol-free skin cream. Apply the cream using a circular motion. Check the person’s skin each day for signs of pressure sores such as reddening. If you see any changes in the skin, tell the doctor; a pressure sore may be forming.

Remove soiled underwear (including disposable briefs) promptly. Be sure to keep sheets pulled tight to prevent wrinkles, and keep them clean, dry, and free of crumbs.

Provide a healthy diet (see page 183) and plenty of fluids to help keep the person’s skin healthy. Eating high-protein foods (such as lean meat, fish, dried peas and beans, and whole grains) and taking nutritional supplements also can help prevent and treat pressure sores.

Bathing

Unless a person is extremely ill, he or she usually can bathe independently with minimal help. Place a large towel under the person to protect the bedding before bringing him or her a basin of warm water, mild soap, and a washcloth. Be sure that the room is warm, and provide another large towel to drape over the person for warmth and privacy. The person should give himself or herself a sponge bath once a day.

If the person you are caring for is unable to bathe without help, you can give him or her a bath in bed. Although giving a bed bath presents its own challenges, it is not a difficult task to perform once you have mastered the routine. Make sure that the room is warm before undressing the person, taking care to provide as much privacy as possible. Cover him or her with a large towel and place another towel underneath to protect the bedding. Before you begin, check the water to make sure it is at a comfortable temperature. When you use soap, make sure it is a mild soap that will not dry out or irritate the person’s skin.

As you bathe the person, look carefully for sores, rashes, or other skin problems. If the person is recovering from surgery, be sure to examine the incision carefully to make sure it is healing properly. Some indications of possible infection include fever; redness, pain, and swelling around the incision; and pus. It is important to report any of these signs to the doctor or nurse immediately.

When giving a bed bath, wash and dry one area of the person’s body at a time, uncovering only the part of the body you are washing. This helps keep the person warm and maintains a sense of privacy.

Follow these steps:

1. Use plain water to bathe the person, starting at the head. Use soap only in sweaty areas (such as the armpits, groin, and buttocks); wash between skin folds. Be thorough but gentle. Change the water as needed.

2. Gently pat the person dry with a fresh, soft towel; don’t rub.

3. Roll the person onto one side to wash and dry his or her back.

4. Let the person dip his or her hands into a basin of fresh water. This is more refreshing than having the hands wiped with a washcloth.

5. Before helping the person dress, make sure that every area of his or her body is thoroughly dry. Provide or apply deodorant, lotion, or body powder as needed.

Helping With Toileting Needs

Bladder and bowel movements can be difficult for people who cannot use the toilet. A person who is confined to bed will need to use a bedpan or commode; a man may be able to use a handheld urinal. If a person cannot use these devices, he or she may need to wear absorbent disposable briefs. Always give the person complete privacy.

If the person cannot wipe after urinating or having a bowel movement, you will need to do it for him or her. Keeping the genital and anal areas clean helps prevent the skin from breaking down. Always wipe a woman or girl gently from front to back (from the vagina to the anus) to ensure that bacteria do not enter the vagina or urinary tract and cause infection.

Some caregivers need to give an enema (by injecting a liquid into the rectum) to relieve constipation (see page 769) or an accumulation of hardened feces in the rectum (fecal impaction). If the person has an indwelling catheter (a plastic tube inserted directly into the bladder) that drains urine into a bag, you will need to empty and clean the bag regularly. (A doctor or other health care professional will change the catheter periodically.) Learn to perform these tasks correctly from a trained health care professional. Ask for clear, precise instructions.

Using a Commode

If the person is able to get out of bed for brief periods, using a bedside commode may be easiest. Assist the person out of bed and onto the commode. If necessary, help the person wipe himself or herself, and then help him or her back into bed. Empty the removable pan into the toilet. Rinse the pan out, clean it thoroughly with a household disinfectant diluted with water, and return it to the commode.

Using a Bedpan

A person who is confined to bed will need to use a bedpan, which can be awkward. In addition to giving the person privacy, be sure to give him or her plenty of time. A person who is embarrassed about using a bedpan or who feels pressured while using one may be reluctant to ask for it when he or she needs it. Resisting the urge to have a bowel movement can lead to constipation and fecal impaction. Remember to ask the person frequently if he or she needs to use the bedpan—and keep it within easy reach and in the same place so it can be found quickly when needed.

Before giving the person a bedpan, sprinkle a small amount of body powder on the rim of the bedpan to make it easier to slip under the buttocks. The open end of the bedpan should always be toward the person’s feet. Keep toilet paper and moist towelettes within easy reach and help the person with cleanup if necessary. After use, empty the contents of the bedpan into a toilet and rinse and wash the bedpan with a household disinfectant diluted with water.

A person who cannot lift himself or herself up may be able to use a bedpan with assistance. If possible, have someone help you. Lift the person’s hips while the other caregiver places the bedpan beneath the person’s buttocks. If another caregiver is not available, roll the immobile person away from you onto his or her side. Gently position the bedpan against his or her buttocks and press the bedpan firmly into the mattress while rolling the person back on top of it. To remove the bedpan without spilling its contents, hold it firmly in place and gently roll the person away from you, and off the bedpan. Thoroughly clean and dry the genital and anal areas.

Using a Handheld Urinal

Always keep a handheld urinal in the same place and within the man’s easy reach. Have him put the urinal in a large bowl or bucket to prevent and contain spills until you can empty it. Empty the urinal into a toilet after each use, rinse the urinal, and wash it thoroughly with a household disinfectant diluted with water.

Monitoring Symptoms

As a person’s main caregiver, you are in the best position to observe any changes in his or her condition that may indicate an improvement or decline in health. What you need to watch for depends on the person’s illness or injury. In general, it is important to closely watch his or her alertness, memory, mobility, vision, hearing, emotions, sleep patterns, eating habits, personal interactions, and sensory responses such as touch. Even small, seemingly insignificant changes can indicate a serious underlying health problem and should be reported to the doctor or nurse as soon as possible. Common signs to watch for include:

• Changes in breathing patterns, including shallow breathing, hyperventilation (abnormally deep, rapid, or prolonged breathing), raspy breathing, gurgling noises in the throat, temporary cessation of breathing (including during sleep), difficulty breathing, or wheezing

• Changes in mobility such as limping, problems maintaining balance, restricted use of arms or legs, or paralysis

• Tremors, shaking, facial tics, twitching, drooping eyelids or mouth, or facial paralysis

• Unusual sneezing or coughing

• Discharge, such as through a bandage; a bloody nose or leaking eye; or pus oozing from an open sore

• Fever, chills, or sweating

• Insomnia (difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep) or fatigue

• Constipation, diarrhea, loss of bladder or bowel control, or vomiting

• Changes in urination or bowel movements, including frequency, smell, appearance, and quantity, and pain or difficulty urinating or moving the bowels

• Changes in skin appearance, including rashes, sores, tenderness, dryness, moistness, itchiness, pallor (paleness), jaundice (yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes), or swelling

• Unexplained weight loss or gain

• Changes in appetite

Incontinence

Incontinence, the inability to control the passage of urine (urinary incontinence) or stool (fecal incontinence), usually is caused by an underlying disease or condition. Urinary and fecal incontinence can occur separately or together. Do not accept incontinence as a normal part of aging. An older person who is experiencing problems with incontinence should be examined by a doctor as soon as possible.

Incontinence can be a major problem when caring for a person at home. One way to deal with incontinence is to establish a toilet routine: encourage the person to go to the bathroom at frequent, regular intervals (for example, every 2 to 3 hours). Provide help promptly to prevent accidents. Make sure that the toilet facilities are readily accessible and easy to use. If the person is confined to bed, make sure that a commode, bedpan, or handheld urinal is within easy reach.

A number of incontinence aids, such as absorbent incontinence pads, disposable briefs, and condom catheters are available from drugstores and medical supply companies. Ask your doctor about them.

If a person has both urinary and fecal incontinence, loss of bladder control usually occurs before loss of bowel control. His or her doctor will examine the person to find the underlying cause.

Depression

A person who is ill or disabled is at high risk for depression. In older people, early detection and treatment of depression are extremely important because of the high risk of suicide. If you notice that the person you are caring for has any of the following signs or symptoms for more than a few days, talk to his or her doctor immediately:

• Changes in appetite (decrease or increase)

• Weight loss or weight gain

• Changes in mood or emotions

• Lack of responsiveness or attentiveness

• Loss of interest in favorite activities

• Feelings of hopelessness or helplessness

Some people incorrectly assume that symptoms of depression are a normal part of aging or mistake symptoms of depression for Alzheimer’s disease (see page 688), dementia (see page 689), or another illness. If the diagnosis is depression, it can be successfully treated with medication, psychotherapy, or a combination of both, at any age.

Fever

Although a fever is not usually dangerous, notify the person’s doctor if the person you are caring for has a fever. Always check with the person’s doctor before giving aspirin or an aspirin substitute. The doctor may prescribe a medication to reduce the fever. If the person’s temperature continues to rise after he or she has been given medication to reduce it, call his or her doctor immediately. Never try to raise the temperature of a person who has a fever (such as by turning up the heat or putting extra blankets or other coverings on him or her). Raising a person’s temperature abnormally high can cause seizures or loss of consciousness.

To help reduce the person’s temperature, sponge his or her face, neck, trunk, arms, and legs with lukewarm water and let it evaporate on the skin. Evaporation brings down the temperature of the skin. Encourage the person to drink plenty of water, a sports drink, fruit juice, or broth to replace the fluids that will be lost through the excessive perspiration that accompanies a fever.

Vomiting

Medications and treatments such as radiation therapy can cause nausea and vomiting. However, because vomiting can also be a sign of an illness or underlying health problem, tell the doctor if the person you are caring for is vomiting, especially if he or she is vomiting repeatedly. The doctor may tell you to watch for signs of dehydration such as thirst, dry lips and mouth, dizziness, headache, confusion, muscle weakness, shakiness, and a reduced output of urine. Dehydration is a potentially dangerous condition that can lead to coma and death.

If the person is confined to bed or cannot get to a bathroom quickly, leave a container (such as a bowl or dishpan) at the bedside for him or her to vomit into. Some people want to be left alone when vomiting, while others find it comforting to have someone with them. If the person finds it reassuring, hold his or her forehead while he or she is vomiting. After the person has vomited, offer some water to rinse out his or her mouth and a bowl to spit into. Then gently wipe off his or her face using cool or lukewarm water.

As soon as the nausea ends, give sips of water, tea, ginger ale, broth, or fruit drinks to replace lost body fluids. Unless told to do so by the doctor, do not give the person solid food for several hours after he or she has stopped vomiting, and then give something that won’t upset his or her stomach (such as gelatin).

Memory Problems

People of all ages can forget to call a relative on his or her birthday or leave some of the ingredients out of a favorite recipe. These types of memory problems are normal and do not interfere with the ability to function. More serious memory problems sometimes accompany aging. When an older person realizes that his or her memory is not as good as it once was, he or she may begin to feel apprehensive, fearful, and anxious. Forgetfulness may cause an older person to assume that he or she is developing dementia (see page 689) or Alzheimer’s disease (see page 688). Reassure the person, and try the following strategies to help him or her remember better:

• Make signs to remind the person to do things such as take medication, turn off the stove, or lock the doors. Place the signs in a visible location. Put signs along the way to the bathroom, with a sign that reads “BATHROOM” attached to the bathroom door.

• Give the person a large calendar with large numbers to help him or her keep track of dates and events by checking off each day of the week.

• Circle dates on the calendar as a reminder of important appointments and dates.

• Provide clocks with large, easy-to-read numbers to help the person stay time-oriented.

• Follow a regular mealtime schedule; people with memory problems often forget to eat.

• Post a daily checklist on the refrigerator door to remind the person of the things he or she needs to do.

• Place items to bring upstairs near the foot of the stairs (but never on the stairs).

• Place items to be taken along on outings near the front door.

• Label boxes with their contents so the person will know at a glance what is inside.

• Store items such as keys, eyeglasses, and medications in the same place (and be sure to always return them to their proper place) so they are easy to find when needed.

• If the person is disoriented, have him or her wear an identification bracelet at all times. It should list the person’s name, address, and telephone number. This identification will be helpful if he or she wanders away or becomes lost.

If the person’s memory problems begin to interfere with day-to-day living, he or she should be examined by a doctor who has experience diagnosing and treating people with Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia.

Reducing the Risks of Immobility

Many people who are confined to bed develop health problems from immobility. Because of the potential risk of problems with circulation, breathing, and muscle stiffness, a person who can get out of bed needs to do so regularly.

Increasing Circulation

Immobility decreases a person’s heart output, or circulation, increasing his or her chances of developing blood clots. A person’s heart rate, or pulse, is a good indicator of how well his or her cardiovascular system can handle being out of bed.

If the person’s heart rate is between 50 and 100 beats per minute when out of bed and sitting in a chair, it may be OK for him or her to stay up. If the person’s heart rate is higher than 100 beats per minute when sitting in a chair, sitting up may be too strenuous; ask his or her doctor if the person should stay in bed.

The person’s doctor may suggest that the person start exercising in bed to increase his or her strength and endurance enough to get out of bed. Always check with the person’s doctor first before starting an exercise program. These simple exercises may include range-of-motion exercises (see next page), turning from side to side in bed, and sitting on the edge of the bed for short periods of time. If the person’s heart rate goes below 50 beats per minute or above 110 beats per minute, call his or her doctor right away. A heart rate below 50 beats per minute could indicate problems such as dehydration, anemia (see page 610), or heart failure (see page 570). A heart rate above 110 beats per minute could indicate problems such as an arrhythmia (see page 580) or high blood pressure (see page 574).

In the carotid artery

In the radial artery

Checking a pulse

To check a person’s heart rate, place your index and middle fingers on the artery inside his or her wrist or along the artery at the side of the neck. (Do not use one of your thumbs to take a person’s pulse because you could mistake your own pulse in an artery in your thumb for the person’s pulse.) You should be able to feel blood pulsing in the person’s artery as his or her heart beats. Count the number of beats that occur in exactly 20 seconds and multiply this number by 3. The resulting number is the person’s heart rate.

Maintaining Lung Function

Being immobile reduces lung function and increases the risk of pneumonia, so it is important to maintain lung function in a person who is confined to bed. If the person’s doctor has recommended it, encourage the person to cough and do deep breathing exercises every hour while awake to expand his or her lungs. Encourage the person to breathe through his or her nose as deeply as possible and then breathe out through the mouth slowly but forcibly.

If possible, obtain a device called a spirometer (which is used to measure air expulsion) from a respiratory therapist and have him or her show you how to help the person use it.

WARNING!

Difficulty Breathing

Call the person’s doctor immediately if the person you are caring for has difficulty breathing or coughs up green, gray, yellow, or brown phlegm. He or she may have pneumonia.

Preventing Deep Vein Thrombosis

Blood clots are another potential complication of immobility. They usually develop in the veins of the legs. If the person cannot bear his or her own weight or walk, ask the doctor if the person should move his or her legs while in bed to prevent blood clots. Also, ask the doctor about using special elastic stockings that can help prevent blood clots from forming in the legs. Don’t massage the person’s legs unless told to do so by the doctor.

WARNING!

Pulmonary Embolism

Never massage the legs of a person who is confined to bed. Massaging an immobile person’s legs (especially the calves) can dislodge a blood clot, which can then travel through the bloodstream to the lungs, causing a life-threatening blockage of an artery (pulmonary embolism; see page 606). Symptoms of pulmonary embolism include difficulty breathing, pain in the chest, rapid pulse, sweating, slight fever, and a cough that produces blood-tinged phlegm. If these symptoms occur, call 911 or your local emergency number, or take the person to the nearest hospital emergency department right away.

Keeping the Arms and Legs Strong

A person begins to lose muscle strength after being confined to bed for just 1 day; after 1 week in bed, he or she may be too weak to stand up. A period of bed rest often is required after surgery or a major illness. A person who is confined to bed for any reason must be encouraged to change positions frequently to prevent joint stiffness, loss of muscle tone, and contraction of the limbs from prolonged inactivity.

To help prevent joint stiffness, carefully place the person’s arms and legs in comfortable, natural, strain-free positions and support them on pillows, cushions, or pads. Rest the person’s elbows on pillows, and keep his or her legs from turning outward with foam-rubber cushions or pillows. Support the person’s feet with a footboard to prevent footdrop (a condition in which the foot hangs limply from the ankle). Place the person’s hands around small rolls of foam-rubber padding.

Supporting the feet with a footboard

Supporting the hand with foam-rubber padding

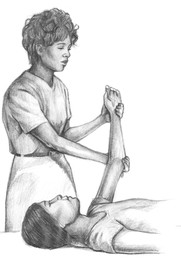

Range-of-motion exercises will help prevent a bedridden person’s hands, arms, and legs from stiffening and contracting. The person should move each limb up and down and away from and toward the middle of the body. This process is called active range of motion. If the person cannot move a limb, the caregiver should perform passive range-of-motion exercises. Gently hold the person’s limb at each joint and move the limb in all the directions in which it can move normally. These exercises also help stimulate blood circulation and help prevent blood clots from forming in the legs. A visiting nurse can teach you how to correctly perform range-of-motion exercises.

Exercising the leg

Range-of-motion exercises

If the person you are caring for is immobile or has difficulty moving, help him or her to perform range-of-motion exercises to prevent the hands and limbs from contracting. Gently bend and straighten each elbow and wrist, and the fingers and thumb of each hand. Raise each leg, bending and straightening the hip, knee, and ankle.

Straightening the elbow and wrist

Bending the elbow and wrist

Encourage the person to move each joint through its entire range of motion several times a day. To prevent injury, do not try to move any joint that resists motion. Never move any limb beyond the point at which it causes discomfort or pain. If resistance or pain occurs, tell the doctor as soon as possible.

Helping the Person Get Out of Bed

A person who has been confined to bed for a long time is likely to feel weak and dizzy when getting out of bed for the first time. To prevent a fall, have the person sit up slowly and rest on the edge of the bed for a few minutes before trying to stand up. Place a sturdy chair beside the bed. When the person feels steady, stand directly in front of him or her so he or she can lean on you for support. Hold the person under the arms. Then help the person turn slowly, and gently and carefully lower him or her into the chair. As the person begins to feel stronger, have him or her try to take a few steps, using your arms for support.

Positioning an Immobile Person in Bed

A person who is confined to bed often tends to slide toward the foot of the bed. To move an immobile person toward the head of the bed, you first need to help him or her to a sitting position.

An immobile person’s body should always be properly positioned to help prevent deformities. Proper positioning can be achieved using pillows and bolsters. For example, when a person is lying on his or her side, instead of elevating the head of the bed, place a pillow under the upper leg and arm. And place a pillow or bolster behind the person’s back to prevent him or her from rolling backward. A person who has little fat on the hips should not be positioned fully on his or her side. Instead, position him or her in a 30-degree side-lying position to help prevent the development of pressure sores in the hip area.

Moving a Person in Bed

1. To help the person sit up in bed, first arrange the pillows so that his or her shoulders are elevated. Cross the person’s arms at his or her waist. Place your hands over the person’s shoulders and place your knee on the bed, next to his or her hip. Place your other foot firmly on the floor next to the bed, slightly ahead of your knee and even with the person’s waist.

2. Firmly grasp the person’s shoulders, keeping your arms straight, and slowly move back, using your weight to pull him or her up toward you.

3. If you want to move the person toward the head of the bed, keep your hand on the shoulder closer to you and get in position behind him or her. Place your knee on the bed behind the person and place your other foot firmly on the floor. Cross the person’s forearms in front of his or her waist and hold them firmly from behind. Slowly move back, using your weight to pull the person toward you.

An immobile person who is confined to bed should not remain in the same position for longer than 2 hours while the caregiver is awake. Move the person from his or her side, onto his or her back, and onto the other side every 2 hours. When the immobile person is on his or her back, position a pillow under each arm and on the side of each thigh to prevent outward hip rotation. Also, place a small pillow under the knees and a footboard at the foot of the bed to keep the person’s feet positioned at a right angle to the mattress. This positioning will prevent the development of footdrop (a condition in which the foot hangs limply from the ankle) and keep the person from sliding down the bed.

Do not tuck sheets and blankets tightly around the person’s feet and legs; keep blankets and other coverings elevated with a bed or foot cradle (a tentlike device placed at the foot of the bed). Keep bottom sheets taut to prevent them from wrinkling or gathering under the person’s body, which could cause pressure sores.

When feeding a person in bed, elevate the head of the bed at least 30 degrees to prevent choking, and keep the bed raised for at least an hour after eating. This positioning helps prevent the person from regurgitating food, which can cause him or her to accidentally breathe food into the lungs and choke. Breathing foreign particles into the lungs can lead to pneumonia.

Moving an Immobile Person

When moving an immobile person to a chair, wheelchair, or commode, wear sturdy shoes with nonskid soles, and make sure that the person you are moving is also wearing sturdy, nonskid shoes or slippers. To prevent falls, do not attempt to move a person who is barefoot or wearing only socks. You may need to use a transfer belt, a specially designed belt that is placed around the person’s waist. The belt provides leverage and makes it easier to firmly grip the person when you help him or her to a standing or sitting position. Your doctor, nurse, or home health aide can teach you how to use a transfer belt properly. You can purchase one from a medical supply company.

WARNING!

Transfer Belts

Never use a regular belt as a transfer belt when moving an immobile person or you could cause serious injury to the person.

Before you move the person:

• Talk about each step with the person.

• If you are moving the person from a hospital bed, lock the bed’s brakes.

• If you are moving the person to a wheelchair, lock the wheelchair’s brakes.

• If needed, put a transfer belt on the person.

To move an immobile person:

1. Carefully help the person to a sitting position on the side of the bed, with his or her feet on the floor. If the person has been confined to bed for a long time, allow him or her to rest on the edge of the bed until he or she feels secure. Stand directly in front of the person, and brace his or her knees with your knees. Carefully slide the person’s hips toward you.

2. Help the person to a standing position, using the transfer belt if necessary, to firmly hold him or her around the waist.

3. Slowly pivot the person around until his or her back is directly in front of the chair, wheelchair, or commode; have the person feel the seat of the chair or commode with the back of his or her legs before attempting to sit.

4. Slowly lower the person to a sitting position. Once he or she is securely seated, remove the transfer belt.

To help the person back into bed, perform the steps described above in reverse order. Be sure to lock the brakes on the bed and wheelchair before you begin, and use the transfer belt. If you are using a hospital bed, don’t forget to raise the bed rails after the person is back in bed.

Modifying the Home Environment

A safe environment is often the most immediate concern when an older or disabled person lives alone. Take a careful look around the home and take the following steps to make the home safe:

• Modify the home as needed to help prevent falls (see below right).

• Install smoke alarms (especially near bedrooms and the kitchen) and a carbon monoxide detector. Check the batteries frequently and replace them on the same day every year, whether they need it or not.

• Plan an escape route in case of fire. Have regular fire drills.

• Keep a clear path to all doors that lead outside.

• Set the temperature of the water heater below 110°F to prevent burns.

• Keep a fire extinguisher in the kitchen, and learn how to use and maintain it properly.

• Repair or replace any electrical appliances that have frayed wires or damaged plugs.

• Do not overload electrical outlets.

• Remove electrical cords from under rugs or carpets.

• Install deadbolt locks on outside doors, sturdy locks on all windows, and motion-detector lights on the grounds of the home.

• Have the furnace and thermostat inspected by a qualified professional.

Organizing the Room

When organizing the person’s room, think about his or her needs. Consider how ill he or she is and how long you are likely to be caring for him or her. Arrange the room to make it as comfortable and convenient as possible for the person who is being cared for and the caregivers. Here are some helpful tips:

• In a two-story house, it is better for the person to stay on the first floor. He or she will feel less isolated, you will eliminate a lot of trips up and down the stairs, and you can prevent falls.

• Provide a single bed, positioned so it is accessible from both sides. If you need a hospital bed, you can rent one from a medical supply company.

• Provide a bedside table stocked with medications, water, tissues, a whistle or bell (to call for help), and any other important items.

• If the person can get out of bed but cannot get to the bathroom easily, you will need to get a commode (a portable chair that contains a removable bedpan). You can rent or buy one from a drugstore or medical supply company or, in some communities, borrow one from a local health agency or volunteer organization. If the person is confined to bed, keep a bedpan (and a handheld urinal for a man or boy) near the bed at all times.

• Keep the temperature in the room comfortable and the air circulation adequate, but keep the room free of drafts.

Preventing Falls

Carefully and thoroughly inspect the house or apartment of the person you are caring for and make all necessary changes to help prevent falls. Here are some things you can do:

• Make sure that light switches are within easy reach of doorways so the person does not have to cross a dark room to turn on a light. Lighting that is too dim can make it difficult to see. Use high-watt bulbs but make sure they are frosted to reduce glare.

• Place a lamp within reach of the person’s bed. Put night-lights along the pathways between the bedrooms and the bathroom and a night-light in the bathroom.

• Remove loose rugs, mats, and runners. Make sure that all other carpets and rugs have slip-resistant backing or that they are tacked down to prevent trips and slips.

• Arrange furniture so the person has a clear, unobstructed path from one place to another. Keep hallways and stairs clear and uncluttered. Take special care with placement of furniture that has sharp or pointed corners or that is easy to bump into or fall over such as ottomans and coffee tables. Remove any furniture that is not being used. Provide a remote control for the television.

• Keep telephone and electrical cords out of pathways.

• Provide sturdy handrails on both sides of all stairways, 30 inches above the steps. Use nonskid treads on all bare steps. If a stairway is carpeted, make sure that the carpeting is tacked down securely on every step. Do not put loose rugs at the top or bottom of stairways. All stairways should be well lit. Do not keep toys or other items on stairs. Have an electric stair lift installed if the person can no longer climb the stairs. If there is a bathroom on the first floor, move the person’s bedroom there.

• Make sure chairs and tables are sturdy, stable, and balanced in case the person leans on them for support.

• Set the thermostat at a warm temperature (at least 72°F) to help keep an older person’s joints from stiffening. Stiff joints can lead to falls.

• Place guardrails on the bed or a sturdy chair bedside to help the person get in and out of bed. Place a telephone with volume control and a lighted dial next to the bed.

• Place a nonslip rubber mat on the floor in front of the sink. Clean up spills on the floor and countertops immediately. Keep frequently used items within easy reach to avoid having to bend or climb up on a chair or stepladder to reach them. Be sure that the person wears low-heeled, slip-resistant shoes that fit properly.

• Put a nonslip rubber mat or nonslip adhesive strips on the floor of the tub or shower. Install handrails and grab bars that are attached to underlying studs on the walls around the toilet and along the bathtub. Tell the person you are caring for never to use towel bars for support—they are not strong enough. Place a nonslip bath mat on the floor outside the tub or shower. Some people find an elevated toilet seat easier to use.

• Do not lock the bathroom door. It may be necessary to remove locks to prevent the person from accidentally locking himself or herself in the bathroom.

• Have all medications reviewed by the person’s doctor to be sure that they are necessary, especially drugs with possible side effects such as drowsiness, dizziness, or fainting.

• When going outdoors, have the person wear comfortable, sturdy walking shoes with soles that grip the pavement. If he or she uses a cane or walker, make sure it is sturdy and in good condition. Encourage the person to stay indoors, if possible, when the weather is bad, especially when the pavement is wet or icy. During the winter, keep porches, steps, sidewalks, and driveways clear of snow and ice. Always spread sand or salt on icy surfaces.

• A person who has difficulty walking may benefit from working with a physical therapist, either as an outpatient or through a home health care agency. If walking is a problem, talk to your doctor about having a gait evaluation and starting an exercise program to improve the person’s ability to walk and increase his or her strength.

In spite of the best preventive measures, falls still may occur. If the person you are caring for falls, don’t move him or her; try to determine the nature and extent of any injuries, and call for emergency medical assistance immediately.

Regulating Home Temperature

As you age, your body becomes less able to regulate temperature. A life-threatening drop in body temperature (hypothermia; see page 165) can develop quickly in an older person if the room temperature is lower than 65°F. Make sure that the heating system in your loved one’s home is in proper working order and that there is enough heat throughout the day, especially if the person lives in an apartment building, where tenants usually do not have control over the heat. It also is vital to have the furnace checked regularly for carbon monoxide leaks.

Older people also are vulnerable to the effects of high temperatures, which can lead to life-threatening conditions such as heat exhaustion and heatstroke (see page 166). Experts strongly recommend that room temperature be maintained at a constant 72°F, if possible. In the summer, fans may be helpful, but in many parts of the United States, air-conditioning is the only way to keep the temperature at a comfortable level. However, many older people do not own an air conditioner or cannot afford to pay high electric bills. Watch the person carefully for signs of heat exhaustion and heatstroke. In some communities, social service agencies provide air conditioners free to older people on limited incomes. Check with your local area agency on aging for more information.

Personal Emergency Response Systems

Personal emergency response systems (PERS) provide an easy way for a disabled person to call for help in an emergency. The system includes an electronic monitor (about the size of a small radio or answering machine) that can be placed on a bedside table. The monitor is plugged into an electrical outlet and connected to the person’s telephone line. Most systems require the person to push a help button to activate the system. There is a button on the monitor and also on a wristband or pendant that the person wears at all times. Some systems also may be voice-activated or use motion detectors.

When the system is activated, the signal goes to a monitoring center, where a response is set into motion. First, the center attempts to contact the person. Depending on the situation (or if the person does not respond), the center then attempts to contact a designated person or people (such as a relative, friend, or neighbor), or calls for emergency assistance (from emergency medical services, the fire department, or the police).

Personal emergency response systems are available by subscription in many communities, usually with a one-time installation charge and a monthly fee. In some communities, local hospitals, fire departments, and various community organizations provide this service. If the person has limited income and assets, the service may have a reduced fee or be free. In any case, you should not have to purchase any equipment or sign a long-term contract. Ask your doctor or contact your local hospital for information about these systems.

Telephone Check-in and Reassurance

Telephone check-in and reassurance services provide a way of monitoring the health and safety of an older person who lives alone. Paid staff or trained volunteers call the person at home at prearranged times throughout the day. If there is a problem or if the person does not answer the phone, the caller will follow specific procedures such as contacting a doctor or a designated family member, or calling for emergency assistance. These services also can provide older people with companionship and a sense of security. Contact your doctor, nurse, social worker, or local hospital for information about the availability of telephone check-in and reassurance services in your area.

Care for the Caregiver

Taking good care of yourself is an essential part of good caregiving. Because successful caregiving requires an enormous amount of time and energy, it is vital that you remain physically and emotionally healthy. Don’t be shy about asking for and accepting help from others.

Taking Care of Yourself

Keeping yourself healthy physically, mentally, and emotionally will enable you to provide the best care possible to a person who is ill. Here are some guidelines that will help you cope with the demands of caregiving:

• Set realistic goals and limits. Educate yourself about your loved one’s condition so that you know what to expect, now and in the future. Knowing what to expect will help you to adjust your care plan as time passes. Decide under what conditions you will no longer be able to care for your loved one at home, and begin planning for that possibility well in advance. For example, if your loved one has a terminal illness, find out about hospice programs.

• Learn all you can about caregiving. There are many sources of useful information, including libraries, hospitals, agencies, and associations. Ask your doctor, a nurse, or a hospital social worker for information sources.

• Do not confuse doing with caring. Let your loved one remain as independent as possible for as long as possible. Resist the urge to do everything, and encourage your loved one to participate in his or her daily care routine.

• Get plenty of rest every day. Every caregiver needs some uninterrupted sleep during the day, every day. Most people need about 8 hours of sleep each day. If possible, sleep at the same time your loved one is sleeping, or try to get some sleep while another caregiver takes over for you.

• Be sure to keep all of your own medical and dental appointments. It is important that you stay as healthy as possible. Arrange to have a dependable family member, friend, or neighbor stay with your loved one while you visit your doctor or dentist.

• Maintain a healthy diet so you have enough energy to get through all of the day’s activities. Eat lots of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and be sure you are getting a sufficient amount of calcium every day. Consider taking a daily multivitamin/ mineral supplement.

• Try to exercise every day. Choose a type of exercise you enjoy. For example, 30 minutes of brisk walking each day will tone your muscles and stimulate your circulation. It also will get you out of the house.

• Do not neglect your personal life. Regularly take time away from caregiving to enjoy yourself and take care of personal business. Continue to participate in the activities you have always enjoyed. Having fun is a good way to relieve stress and take your mind off of caregiving.

• Take advantage of respite care when you need a break. A responsible family member or friend may be able to take over your caregiving responsibilities for several hours each week. Adult day care programs are often available at senior citizen centers and community service organizations, either free or for a modest fee. Some hospitals and nursing facilities provide respite care services for longer periods (from several days to several weeks) for a fee. Your doctor can recommend appropriate respite care services in your area.

• Keep a diary throughout the caregiving process. Writing things down at the end of the day can help you organize your thoughts, express your feelings, and find solutions to problems.

• Try to stay in touch with your feelings and find positive ways to deal with them. It is common for caregivers to experience feelings of guilt, anger, resentment, or depression. When these feelings are not addressed, they can interfere with the caregiving process and have adverse effects on your health. Discussing your feelings with family, friends, and other members of the caregiving team may be helpful. Joining a support group for caregivers can reduce your sense of isolation, help you find ways to cope with your feelings, and solve caregiving-related problems. Watch for symptoms of depression (see page 187); if you are depressed, get professional help as soon as possible.

Asking for and Accepting Help From Others

Share your caregiving responsibilities with others whenever possible to ensure the health and well-being of the person being cared for, and your own health and well-being. Get in the habit of asking for help as soon as you need it. Do not wait until a situation becomes unmanageable. Every member of the household should participate or contribute in some way—doing chores, running errands, preparing meals, making telephone calls, or providing company.

Be ready to ask for help by keeping a list handy of all the things that need to be done. For example, ask friends or family to come over and stay with the person so you can go out. To get time on your own at home, ask them to go shopping for you or to accompany the person to the doctor’s office. And do not hesitate to accept help when it’s offered.

If you cannot rely on friends, neighbors, or family members, ask your doctor for a referral to a visiting nurse association, which can send a nurse to evaluate the situation and provide some needed help. Consider hiring a household helper, home health aide, or companion to help you with day-today tasks. If family members cannot give their time, perhaps they can offer financial support for help you need. Some hospitals and nursing homes have respite facilities where you can bring your loved one for a short period while you go away on a trip, make up the needed sleep you might have lost, or just stay home and enjoy the solitude. Inquire about the governmental services the person may be entitled to that could help you with required tasks—meal delivery service, homemaker service, respite care, shopping service, case management, transportation service, or taxi service. You may want to attend a support group in your community. Ask your doctor to recommend one.

Caregiver Self-Assessment Questionnaire

Caregivers often are so concerned with caring for another person’s needs that they lose sight of their own well-being. If you are a caregiver, answer the following questions and then do the self-evaluation to determine your level of stress.

Self-Evaluation

To determine your score:

1. For questions 5 and 15, count a No response as a Yes, and a Yes response as a No.

2. Total the number of Yes responses.

Interpreting Your Score

Chances are that you are experiencing a high degree of stress if:

• You answered Yes to question 4 or 11; or

• Your score on question 17 is 6 or higher; or

• Your score on question 18 is 6 or higher; or

• Your total score is 10 or higher

What Should You Do Now?

If you are experiencing a high degree of stress:

• Consider seeing your doctor for a checkup.

• Consider having some relief from caregiving. Ask the doctor or a social worker about caregiving resources in your community. Contact the National Family Caregivers Association (800-896-3650) and Eldercare Locator (800-677-1116), which can also direct you to caregiving resources in your area.

• Consider joining a support group in which you can learn from and share experiences with other caregivers.

Stress Relief for Caregivers

Caring for a loved one at home can be a major cause of stress for the entire household, but it is especially stressful for the caregiver. The person you are caring for may be confused, angry, or depressed. He or she may be demanding or difficult to please, making you feel inadequate, frustrated, angry, and trapped. You may feel guilty for having negative feelings. Such feelings are understandable, but you need to cope with them so you can go on. Take steps early in your caregiving to arrange for respite care.

Preventing Burnout

Caregiver burnout is physical or emotional exhaustion resulting from the prolonged stress of caregiving. The condition usually occurs gradually; the first signs and symptoms may not appear until long after you have settled into a daily caregiving routine. Burnout affects your ability to provide good quality care. Because different people have different coping abilities, burnout levels vary from person to person. Common signs and symptoms of caregiver burnout include:

• Anger or irritability

• Feeling frustrated or overwhelmed

• Lack of energy; tiring easily

• Feeling isolated

• Crying regularly

• Difficulty handling minor problems or making minor decisions

• Frequent headaches or colds

• Change in appetite

• Sleeping problems

• Skin problems such as acne or rashes

• Inability to concentrate

• Feeling anxious, depressed, or resentful

• Nervous habits (such as nail-biting, chain smoking, or overeating)

To help prevent burnout, have a dependable support system consisting of people you can talk to or visit regularly to express your feelings and discuss concerns. Many caregivers are relieved just to have someone to talk to. If nothing is done to relieve it, burnout can quickly lead to depression. If you have any symptoms of caregiver burnout, seek help from a social worker, doctor, nurse, psychologist, or professional counselor as soon as possible. A visit with your clergyperson also may help.

Relieving Stress

If you are a caregiver, respite can take a variety of forms. It may be something simple, such as enjoying a hot bath at the end of the day or watching a favorite TV show. It can be an organized program, such as adult day care, or a respite care program in which the person you are caring for goes to a health care facility for care or treatment. Or it may take the form of a respite worker or volunteer who comes to stay with the person at home. Either way, you can get away or spend some time at home alone.

Maintain your activities and relationships outside the home as much as possible. If you are employed outside the home, for example, try to keep your job if at all possible. Continue to participate in the leisure activities you enjoyed before your loved one became ill. Accept offers of help from others, including family members, friends, respite workers, and volunteers.

What You Can Do to Help a Caregiver

As a friend or relative of a caregiver, you can do many things to help make the person’s job easier. Although the following actions are relatively simple, they can have a profound, positive impact on a caregiver’s day.

• Keep in touch. Call or visit the caregiver as often as you can. Caregivers often feel isolated, and it can be a great relief to talk with friends or relatives.

• Offer to help. Ask the caregiver what he or she would like you to do. Because many caregivers are reluctant to ask others for help, you may need to be persistent.

• Be a good listener. It is important for caregivers to discuss their feelings and concerns, and doing so can often help relieve stress and anxiety. Let the caregiver know that you are available if he or she needs to talk.

Many people find comfort in sharing their experiences with others in support groups. In such groups, people share their concerns about caregiving or about a specific illness such as diabetes, cancer, or Alzheimer’s disease. Consult your local hospital for information about groups in your area. Your doctor or other members of your health care team also may be able to recommend a support group. The Internet also is a good place to look for a support group that will meet your needs. If you cannot find a support group in your area, consider starting your own.