EXHIBIT 3.1 OMB Circular A-123, Management’s Assessment of Internal Controls, Appendix A

Since the enactment of the Chief Financial Officers Act (CFO Act) and later laws, annual financial statements are now compiled department- and agency-wide and are independently audited. This section provides context for understanding Federal financial statements and discusses the implementation of this reporting requirement. It also discusses internal controls generally and specifically assessing internal control over financial reporting.

Since the Constitution was written, Congress has desired that sounder, more effective internal controls be designed, implemented, and used by Federal Agencies. Congress has held hearings, commissioned studies, and heard speeches and presentations before its committees about the importance of internal controls over financial reporting. Congress’s attempts to address the historically weak and deteriorated controls of the Federal Government are unmistakable and based on the trail of laws addressing the installation and strengthening of controls.

In the single decade of the 1990s, a number of laws were enacted with respect to Federal financial management systems. With few exceptions, parts of each law emphasized the need for strengthened controls. But until 2002 and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX), no law required that any entity, in either the private or the public sector, have a management assessment and public reporting of internal controls over financial reporting and to also have an independent audit of those controls simultaneously with the audit of the entity’s financial statement. In July 2002, Congress sent a clear, simple message to public corporations: “Assess internal controls over financial reporting; audit internal controls over financial reporting.” Similarly, in December of 2004, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) issued revisions to OMB Circular A-123, Management’s Responsibility for Internal Control, subjecting Federal Agencies to similar requirements, but stopping short of requiring a separate audit opinion on internal control over financial reporting.

Federal accounting and reporting today have largely been defined by the CFO Act, Government Management Reform Act (GMRA), and related requirements contained in Federal generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) issued by the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board (FASAB). Since the enactment of the CFO Act, agencies have focused on improving accounting disciplines and financial controls to the point where they can prepare financial statements and receive an unqualified opinion from an independent auditor on an accelerated reporting schedule. This has been no easy task. To varying degrees, the relative size and complexity of Federal Agencies along with the variety of nonintegrated financial-related systems that have arisen over many years have added to the challenge.

However, the annual focus on preparing and auditing financial statements has resulted in improvements in internal control and steady progress toward more reliable budgetary and financial information. A recent report developed by the Federal Chief Financial Officers Council found that:

[A]nnual preparation and audit of agency and Government-wide financial statements, have contributed to the evolution of reliable, timely, and useful financial information in the Federal Government.1

For fiscal year (FY) 2012, 21 of the 24 major Federal Agencies were able to achieve the milestone of an unqualified audit opinion. The results of all agency audits are reflected in Table 3.1.

TABLE 3.1 Summary of FY 2012 Financial Statement Audit Results by Agency

Source: 2012 Financial Report of the U.S. Government, Department of the Treasury, p. 5.

| CFO Act Agency | Audit Results |

| Department of Agriculture | Unqualified |

| Department of Commerce | Unqualified |

| Department of Defense | Disclaimer |

| Department of Education | Unqualified |

| Department of Energy | Unqualified |

| Department of Health and Human Services | Unqualified |

| Department of Homeland Security | Qualified |

| Department of Housing and Urban Development | Unqualified |

| Department of Interior | Unqualified |

| Department of Labor | Unqualified |

| Department of Justice | Unqualified |

| Department of State | Unqualified |

| Department of Transportation | Unqualified |

| Department of Treasury | Unqualified |

| Department of Veterans Affairs | Unqualified |

| Agency for International Development | Qualified |

| Environmental Protection Agency | Unqualified |

| General Services Administration | Unqualified |

| National Aeronautics and Space Administration | Unqualified |

| National Science Foundation | Unqualified |

| Nuclear Regulatory Commission | Unqualified |

| Office of Personnel Management | Unqualified |

| Small Business Administration | Unqualified |

| Social Security Administration | Unqualified |

In 2005, the OMB required agencies to begin reporting their audited financial statements within 45 days after the end of the fiscal year. The accelerated reporting schedule has placed an increased emphasis on internal controls to produce reliable information. Prior to the accelerated reporting requirements, agencies took six months or more to produce audited financial statements. Accelerated financial reporting has transformed Federal accounting operations, financial reporting, and auditing within the Federal Government, elevating the importance of sound internal controls to produce reliable information from quarter to quarter.

For example, key reconciliations could no longer be delayed until the end of the year; there simply was not enough time. Internal controls needed to be improved to the point where reliable quarterly, and even monthly, information could be produced and audited in a timely fashion. The approach auditors took to auditing Federal financial statements also shifted. Audits became more focused on internal controls to determine if they could be relied on to produce accurate financial statements. Purely substantive audits could not be successfully completed in the new accelerated timeline. Producing and auditing financial statements on an accelerated schedule are now routine for most Federal Agencies, representing a significant milestone in Federal financial management.

Also contributing to the shape of the current landscape of Federal financial management is OMB Circular A-123, Management’s Responsibility for Internal Control, Appendix A, Internal Control over Financial Reporting (Circular A-123, Appendix A), which became effective in 2006. OMB Circular A-123 serves as the implementing regulation for the Federal Managers’ Financial Integrity Act (FMFIA). While it has existed since 1982 providing guidance on how Federal Agencies should assess and assert over internal controls, it has not specifically addressed internal control over financial reporting.

SOX, while not applicable to Federal entities, served as an impetus for revisions to Circular A-123 and the development of Circular A-123, Appendix A, requirements specifically related to assessing and reporting on internal control over financial reporting. OMB imposed control assessment and reporting responsibilities, similar to those contained in SOX, on the management of Federal departments and agencies with respect to Federal Agency financial controls. Specifically, it introduced the requirement that management must annually assess and assert to the effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting. Of note is one important difference between this circular and the SOX law: Circular A-123, Appendix A, does not require a separate audit of internal controls over financial reporting. This was determined to not be cost beneficial since Federal audits required internal control testing and reporting.

However, one agency, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), is required by the DHS Financial Accountability Act to have a separate audit opinion on internal control over financial reporting. Other agencies, such as the Social Security Administration, have also routinely sought a separate audit opinion on internal controls but have done so voluntarily.

The effect of OMB Circular A-123, Appendix A, has been significant. It has raised awareness and understanding across the Federal Government in regard to the importance of financial reporting and internal controls. Major Federal Agencies now have in place a structured and consistent process that can be used to provide management with evidence to support its assertion over internal control.

OMB Circular A-123, Appendix A, has also served as an overarching requirement within which other financial management improvement efforts can be integrated and leveraged. For example, opportunities exist for independent financial statement auditors to leverage documentation and testing performed by A-123 assessment teams within Federal Agencies. This would be similar to the way corporate financial statement auditors utilize internal audit resources. Further, the process documentation and testing work performed as part of the A-123 assessment serve as leverage points for streamlining controls and for validating corrective actions. Similarly, the internal control assessment process can be used to conduct related assessments in targeted areas of concern, such as improper payments and detailed financial spending reports. This type of integration and efficiency has yet to be fully realized.

In 1999, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) developed internal control standards for the Federal Government with the publication of what is informally known as the GAO Green Book. The GAO Green Book is based on the Internal Control—Integrated Framework developed by the Consortium of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) of the Treadway Commission in 1992. These standards are incorporated by reference in OMB Circular A-123.

Since its release in 1992, COSO’s Internal Control—Integrated Framework (or the COSO Framework) has become the controls standard for much of the business world. The COSO control concepts have been tested by many and applied in thousands of audits, and have also been adopted by numerous private and public sector organizations as their own controls framework. Efforts are currently underway to update the COSO Framework with an Exposure Draft issued in September 2012 and subsequently, the GAO Green Book.

In the COSO Framework,2 internal controls are broadly defined as:

a process, effected by the governing board, management, and other personnel of an audited entity, that is designed to provide reasonable assurance regarding the achievement of objectives in the following categories:

Under the COSO definition, internal controls encompass or consist of five interrelated structural components:

With respect to information technology-related controls, COSO identified two types:

In 2004, OMB issued revisions to OMB Circular A-123, emphasizing internal control over financial reporting. The revised circular required a separate management assurance statement on internal control over financial reporting and a separate Appendix A, with requirements for assessing financial control effectiveness. The Appendix A guidance was further supplemented in June of 2005 with specific “hands on” guidance for conducting assessments issued by the Federal CFO Council.

Similar to COSO, OMB in Circular, A-123 (2004), described two groupings of internal controls:

Today, Federal Agencies report on internal controls to the President, Congress, and the interested public in two principal formats:

The genesis of the Federal Government’s Performance and Accountability Report is Section 4 of the FMFIA of 1982, which requires an annual statement on whether the agency’s financial management systems conform to government-wide requirements presented in OMB Circular A-127, Financial Management Systems. OMB Circular A-123 is a consolidating policy statement blending financial management requirements of laws, earlier OMB regulations, positions of Federal Inspectors General (IGs), and guidance promulgated over the years by the GAO.

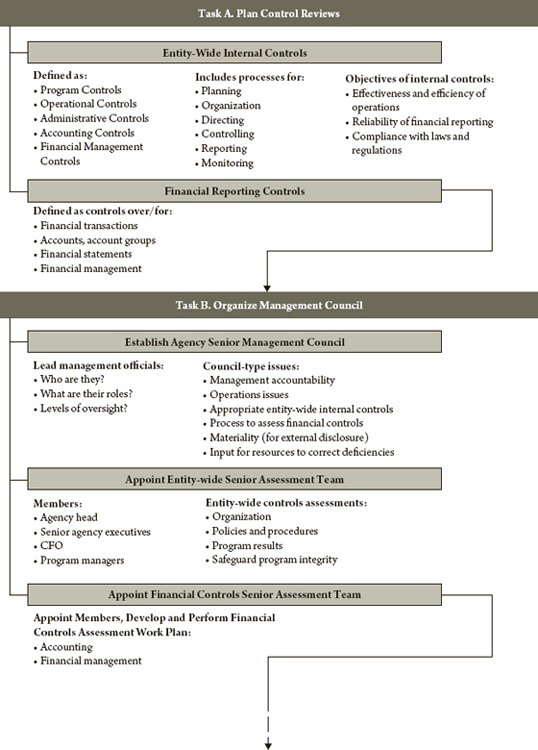

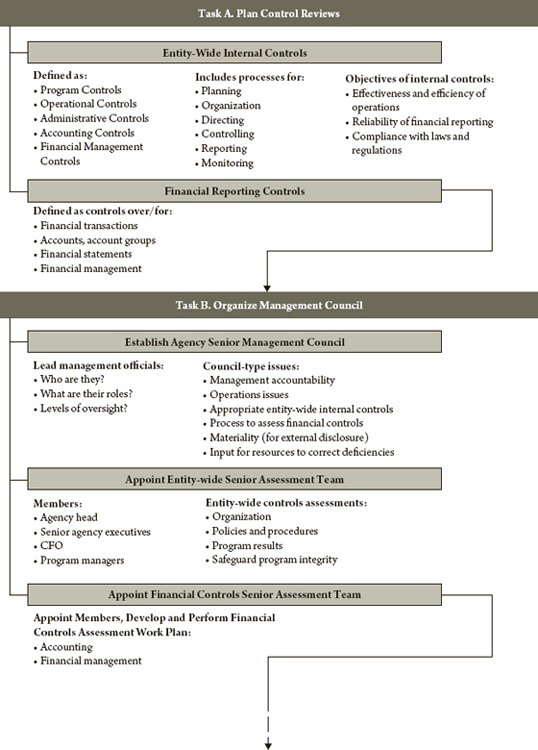

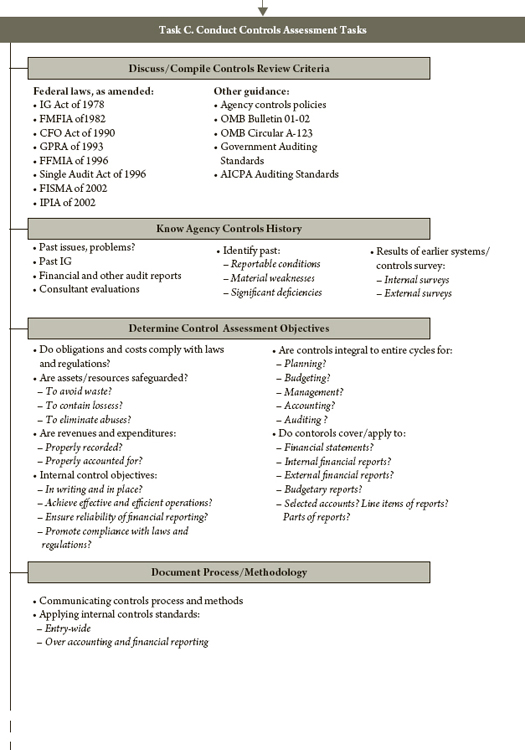

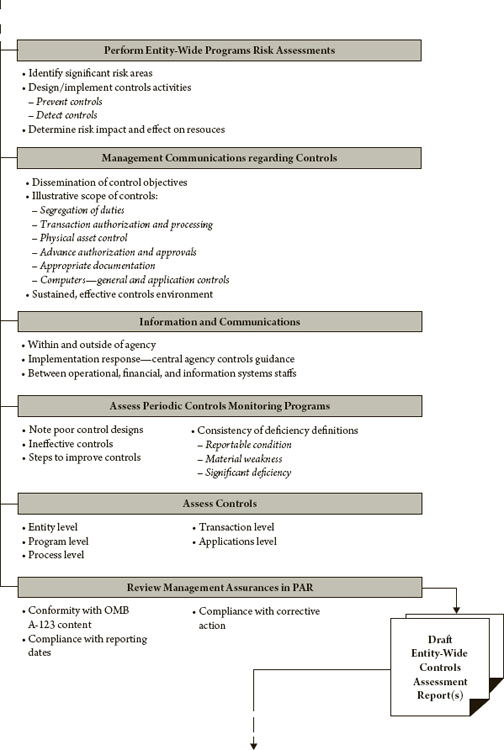

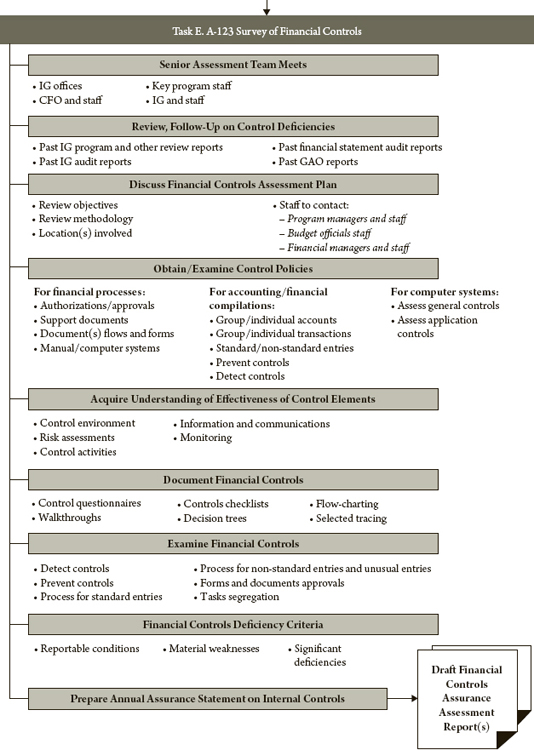

Exhibit 3.1 highlights several tasks required to assess and render an annual statement regarding the effectiveness of an agency’s internal controls to comply with OMB Circular A-123.

EXHIBIT 3.1 OMB Circular A-123, Management’s Assessment of Internal Controls, Appendix A

For Performance and Accountability reporting, the circular states that an agency’s entity-wide internal controls include an agency’s processes for planning, organizing, directing, controlling, and reporting on agency operations. The overall objectives include the effectiveness and efficiency of operations, reliability of financial reporting, and compliance with applicable laws and regulations. The specific statutory guidance considered by OMB in its deliberations on Circular A-123 emanates from:

To comply with the previous statutes and OMB’s consolidating Circular A-123, agency managers must identify and report deficiencies in internal control. While materiality determinations may vary between audits and internal control assessments, the definitions of a control deficiency and material weakness are the same.

A deficiency in internal control exists when the design or operation of a control does not allow management or employees, in the normal course of performing their assigned functions, to prevent or detect and correct misstatements on a timely basis. A significant deficiency is a deficiency, or combination of deficiencies, in internal control that is less severe than a material weakness yet important enough to merit attention by those charged with governance.

A material weakness is a deficiency, or combination of deficiencies, in internal control such that there is a reasonable possibility that a material misstatement of the entity’s financial statements will not be prevented or detected and corrected on a timely basis. At times, the applied definitions related to these circumstances have varied among Congress (in its laws), OMB (in its circulars and bulletins relating to Federal audits), GAO (in its guidance and auditing standards), and the COSO Framework, which has been adopted by the Federal Government as guidance for its practices.

For years, numerous laws and several OMB circulars and bulletins have required audits involving Federal monies to be conducted in accordance with the Government Auditing Standards. However, these auditing standards, issued by GAO, do not require that a Federal Agency’s internal controls be audited. Instead, these standards require only that the internal controls be tested by auditors of Federal financial statements and that the results of those tests be reported. Specifically, the fieldwork and reporting standards for financial audits for generally accepted auditing standards (GAAS) require:

A sufficient understanding of internal control is to be obtained to plan the audit and to determine the nature, timing, and extent of tests to be performed.

This field work standard has been further refined by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants’ (AICPA) Statements on Auditing Standards (SAS), which direct certified public accountants (CPAs) to obtain an understanding of (1) the design of a client’s internal control policies and procedures and (2) whether the control policies and procedures have been placed in operation. This understanding of the controls structure must be documented (e.g., internal control questionnaires, checklists, flowcharts, decision tables, memoranda) by the auditor.

The second and third government auditing report standards require:

As Federal financial management and auditing continues to evolve, issues, and challenges continue to emerge. All of the emerging issues discussed in this section are currently cast in the shadow of the Federal budget. Addressing the uncertainties surrounding the Federal budget is the most prominent financial management emerging issue. It is during these times that the value that disciplined financial management and auditing bring in the form of greater accountability, financial integrity, and credibility is even more important. Accurately accounting for and monitoring Federal spending, maintaining sound internal controls, developing useful information to ensure that funds are spent wisely, and maintaining regular independent auditing and oversight are important for promoting confidence in Federal Government finances. Other emerging issues are discussed next.

The most visible indicator of the foundation of internal controls and accounting disciplines in place today within the Federal Government is the number of agencies with both an unqualified audit opinion and no material internal control weaknesses reported by their independent auditors. Achieving this goal on a government-wide basis is a sign of the financial integrity and credibility of the U.S. government.

At the agency level, achieving this goal requires incremental improvements in financial management operations and a sustained multiyear commitment by agency management and their auditors. Where success has been achieved, management and auditors have worked collaboratively year to year to resolve issues and improve accounting processes and internal controls.

Today, challenges still remain in some agencies to achieve auditable financial statements. The Department of Defense (DOD) has an annual budget of more than $600 billion, more than 3 million civilian and military personnel, and worldwide operations. Its sheer size, complexity, and number of nonintegrated systems processing financial-related information make achieving auditability within the DOD challenging. The National Defense Authorization Act of 2010 has set a requirement for the DOD to be auditable by 2017; recently DOD leadership has accelerated this goal for certain financial statements.

Other large agencies face similar challenges; for example, DHS has the added complexity of being a relatively new Federal Agency that has merged, acquired, and started up new operations. Achieving the milestone of an unqualified audit opinion for DHS and other similar agencies will pave the way for an audit opinion on the financial statements of the U.S. government.

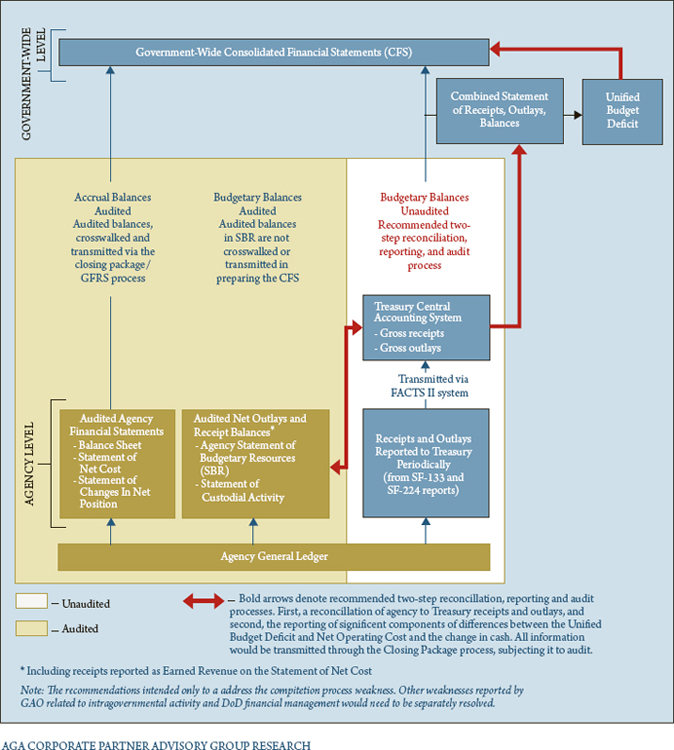

In addition, Treasury is focusing on the compilation process itself. Since 1997, material weaknesses over its compilation process have been reported by GAO, its independent financial auditor. Resolving this weakness entails correcting flaws in the flow and design of information gathered in support of the government-wide statements, mainly budgetary information accounted for in separate general ledger accounts at the Treasury and reported and audited at an aggregate level in agency financial statements. In a recent research report on the topic prepared by the Association of Government Accountants (AGA), the problem was described in these words:

Over the past 15 years, much time and effort have been placed on improving the quality of financial information reported in both agency financial statements and the CFS [consolidated financial statement]. It is fair to say that the majority of the focus to date has been on the accrual basis accounts within an agency. Only one of an agency’s financial statements—the Statement of Budgetary Resources (SBR)—is derived solely from an agency’s budgetary accounts, which are primarily on a cash basis. Information reported in the SBR is aggregated at the agency level, and final audited numbers are not reported further to or used by Treasury. Arguably, budgetary information is the most useful financial information within an agency, yet the lack of a transparent reconciliation process between agency and Government-wide balances has had the effect of inhibiting the audit of probably the most quoted and used number published by the Federal Government—the Unified Budget Deficit.

Exhibit 3.2 illustrates the audited and unaudited data flows supporting the government-wide financial report or CFS. Solving the internal control weakness in the compilation process will entail developing a process to compile and audit the unaudited flow. This flow consists of primarily budgetary information and reconciling items linking budgetary and accrual information reported. Adding transparency and the credibility of an independent audit assurance to this flow of information will add greater integrity to the CFS and other financial information reported by the Federal Government.

EXHIBIT 3.2 Data Flows Supporting Government-Wide CFS

Fully accomplishing the intent of the CFO Act entails evolving Federal financial management beyond a compliance-focused activity to a more value-added program where decision-useful information is routinely developed. Most agencies have achieved the first step toward this goal: having established a foundation of accounting disciplines and internal controls that routinely produce reliable financial statements. The next step is to leverage the foundation to generate information to better meet the needs of agency leadership and program managers to support budget and program management decisions.

To this end, program cost information is noticeably absent from Federal financial management. The development of reliable cost information has been largely centered in agencies where a separate statutory requirement exists or where the agency operates an internal service type fund where fees need to cover the full cost of operations. This pattern continues to hold true today, with only limited areas where cost information is being developed and used. The pressure for this type of information is increasing as the Federal budget tightens. Clear and consistently reported cost and performance information can inform better budget and program decision-making, rather than often used arbitrary, across-the-board approaches where efficient and high performing programs are treated the same as inefficient non-performing programs. Understanding program costs and the relationship of these costs to performance results is essential to achieving the ultimate goals of the CFO Act and to monitoring operational efficiency.

In 2009, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (Recovery Act) became law with the intent to stimulate the nation’s economy. The Recovery Act provided $787 billion, most of which to be spent over a two-year period. To oversee the spending of these funds, a special Recovery and Transparency Oversight Board (RATB) was established to work closely with the Vice President, agency IGs, and the GAO. In implementing the Recovery Act, a number of practices emerged that could potentially shape the future of Federal financial management. According to the AGA Research Report titled Redefining Accountability: Recovery Act Practices and Opportunities:

In implementing the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 [Recovery Act], Federal Agencies have introduced more aggressive risk management, strengthened oversight, incorporated more detailed financial reporting, and implemented other practices to enhance transparency and accountability over Government financial management . . . . [T]hese practices are innovative—and in some cases unprecedented—and have the potential to shape future Government financial management and reporting.3

Advances in technology along with greater sharing of information helped management and auditors meet these challenges. Comprehensive risk assessments were performed to pinpoint trouble areas, sometimes before a financial transaction occurred. One of the best examples of this is within the RATB operations, where the RATB utilized enhanced data mining, management, and sharing techniques to identify high-risk indicators and patterns. Other early-warning assessments, sometimes referred to as flash reports, were issued by agency IGs in an effort to shift their oversight forward to assist in the early identification of risk, supplementing a more traditional after-the-fact audit approach.

Similar risk-based, prevention-oriented approaches are being assessed to reduce Federal improper payments, estimated to be in excess of $100 billion government-wide for FY 2012.4 (The practice of leveraging technology to more proactively address program and financial risk areas is an approach being used more and more in the Federal audit community to prevent fraud, waste, and abuse.)

Today, the realm of Federal financial information publicly reported is broad. It ranges from detailed transaction-level information reported on multiple government-sponsored Web sites to audited financial statements. As access to information becomes easier, reporting financial information meeting user needs becomes more challenging. Public satisfaction with government financial management information continues to be low. According to an AGA survey titled Public Attitudes toward Government Accountability and Transparency conducted in February 2010, the majority of those surveyed were not very satisfied or not at all satisfied with Federal financial management information reported. In addition, Congress frequently requests financial information arrayed in ways specific to meet its immediate needs.

Challenges exist in addressing the variety of user needs while balancing costs and benefits and maintaining consistency and integrity of the information being reported. Addressing this challenge will entail leveraging new technologies to improve access and understanding, while maintaining the internal control, data quality, and credibility benefits that are the hallmarks of the audited financial statement process.

1 Association of Government Accountants, The Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990—20 Years Later, July 2011.

2 Based on a 1992 report by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations, a consortium of cooperating organizations that includes the Financial Executives Institute, American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, American Accounting Association, Institute of Internal Auditors, and Institute of Management Accountants.

3 AGA Research Report, Redefining Accountability: Recovery Act Practices and Opportunities, July 2010, p. 4.

4 Office of Management and Budget, Memorandum M 11-16, April 14, 2011.