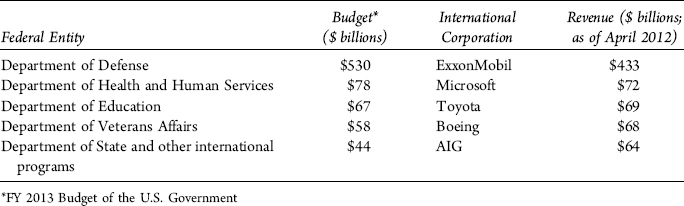

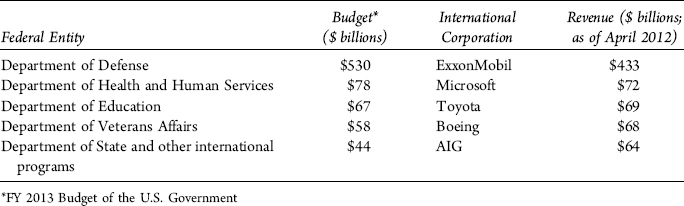

The Federal audit model has many similarities to its commercial counterpart; however, it has just as many significant differences. It is imperative that an auditor be properly trained in the Federal accounting and reporting environment in order to effectively execute a Federal audit. The size of Federal entities is equivalent to the largest of international corporations. No auditor without sufficient training would ever attempt to audit any of these corporate entities.

Second, the hierarchy of generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) is unique for Federal entities. The Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board (FASAB) was designated as the accounting standards-setting body for Federal entities under Rule 203 of the Code of Professional Conduct of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) in 1999. FASAB defined the hierarchy of GAAP in the Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards (SFFAS) 34, The Hierarchy of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles for Federal Entities, Including the Application of Standards Issued by the Financial Accounting Standards Board, in 2009. An auditor must be familiar with this hierarchy and all FASAB pronouncements in addition to laws, regulations, and Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and Government Accountability Office (GAO) guidance in order to audit in the Federal environment. Last, the unique and diverse missions of the Federal Government, its unique assets, and its budgetary accounting and reporting requirements all add additional layers of complexity to the Federal audit process. Auditors must become familiar with the unique characteristics of the specific entity they are auditing before they begin the audit process.

Over the years, virtually every accounting firm and Federal Agency involved in the execution of financial statement audits has developed an audit model along with supporting audit checklists and audit programs to guide the efforts of their staff. GAO, with the President’s Council on Integrity and Efficiency (PCIE), has compiled two manuals directly relevant to the conduct of Federal audits: the Financial Audit Manual (FAM) and the Federal Information System Controls Audit Manual (FISCAM) These documents, superbly researched and the labor of many months, are comprehensive (the three-part FAM is nearly 1,250 pages and FISCAM is another 600 pages) guides based on generally accepted auditing standards (GAAS) covering virtually every possible aspect of a Federal financial audit. The availability of such guidance may make auditors wonder why any planning must be done when such working models and well-defined audit procedures are readily available.

Every audit is unique. Applied audit procedures must be tailored to the conditions and circumstances encountered, which differ not only from agency to agency but within a single agency from one year to the next. Models are very useful in planning, but it does not follow that every audit consists of the execution of predetermined steps or procedures.

Audit manuals are not a substitute for audit judgment. Circumstances and conditions specific to a particular agency may make the application of the FAM guidance entirely appropriate. However, the FAM’s audit model notes that judgment must be exercised in applying the model. It is expected that the tasks and activities suggested will require modification, refinement, and/or supplementation.

The Federal audit model outlined in the FAM provides a framework for performing financial statement audits in accordance with the Government Auditing Standards (Yellow Book), integrating the requirements of the Federal accounting standards and assessing compliance with laws and regulations and internal controls. The Yellow Book incorporates, by reference, all of the generally accepted field auditing standards, audit reporting standards, and attestation standards established by the AICPA.

The methodology outlined in the government’s FAM audit model was also designed to meet compliance requirements prescribed by several other Federal-wide criteria and guidance, such as those prescribed by these organizations or acts:

At the outset of any audit, the auditor must have a clear idea of the objectives of the audit in order to identify an audit scope, audit process, and audit procedures that will achieve those objectives. Naturally, it helps to have a model.

For financial audits, several useful models exist. One such model, applied in the execution of financial audits of Federal Agencies, is the model jointly developed by GAO and the PCIE. Their audit model, as detailed in the FAM and FISCAM, describes an audit of a Federal Agency’s financial statements that is comprised of four phases:

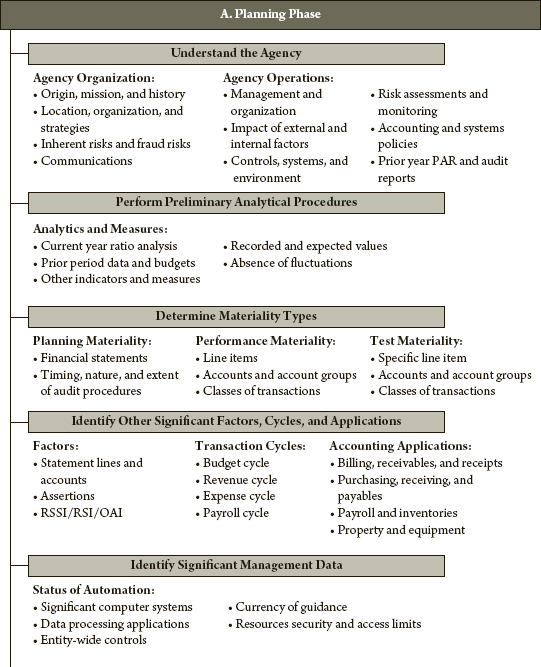

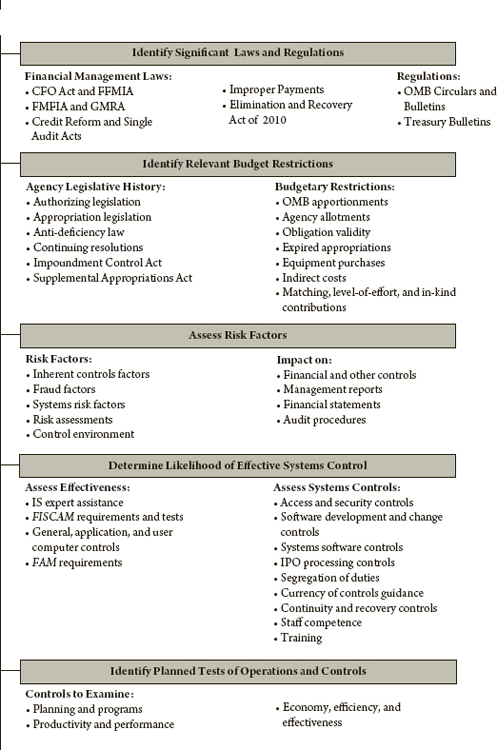

The purpose of Phase I is to develop a preliminary understanding of the operations of the auditee, the auditee’s internal controls and financial systems, including an initial review of the auditee’s computer-based support systems. The auditor’s initial understanding of these systems is augmented during each subsequent phase of the audit, as control systems are further evaluated and tested. It is important to realize that planning a financial audit is not a one-time-only task but rather an interactive process.

An objective of this initial phase of planning is to identify significant areas of risks and issues required by law and regulations to be examined and to design appropriate evaluative audit procedures. To accomplish this, the auditor must conduct a review early on to rapidly acquire an understanding the Federal Agency’s operations, organization, management style and systems, applied internal controls, and external factors that influence its operations. In this phase, it is imperative that the auditor also identify all significant accounts, accounting applications, key financial management systems, material appropriation restrictions, budget limitations, and provisions of applicable laws and regulations.

The planning phase is where the auditor must assess and acquire an understanding of the relative effectiveness of both an agency’s systems of internal financial controls and its information systems (IS) controls, with the objective of identifying high-risk areas, potential risks of fraud, and possible abuses of financial resources.

The purpose of Phase II is to assess and obtain a comprehensive working knowledge of the current state and design of the internal control systems and work flows of a Federal Agency’s significant systems. This includes such systems as budget, financial reporting, procurement, revenue/cash receipts, cash disbursements, payroll, and data processing. At this phase’s conclusion, the auditor should have evaluated the system’s design and related internal financial controls and identified the system’s design strengths and weaknesses and potential audit obstacles that will require refinement of the planned audit approach.

This phase requires internal controls to be assessed to support the auditor’s initial evaluations about the:

The AICPA’s attestation standards, incorporated by reference into the government’s auditing standards, permit an auditor to give an opinion on internal control or on management’s assertion about the effectiveness of internal control. There is an exception if material weaknesses are present; then the opinion must be limited to internal controls and not management’s assertion. Additionally, OMB’s audit guidance includes a third objective of internal control related to performance measures.

Thus, an evaluation of internal controls requires the auditor to identify and understand the relevant controls and assess the relative effectiveness of the controls, which will then be tested later in the audit. Where controls are considered effective, reliance may be placed on such controls, and the extent of later substantive testing (e.g., detailed tests of transactions and account groups) can be reduced. The FAM model methodology includes relevant guidance to:

During the internal control phase, the auditor should understand the entity’s significant financial management systems and test systems compliance with FFMIA requirements.

Phase III encompasses tests of controls and the performance of substantive testing (e.g., tests of the transactions and accounts and the conduct of analytic review procedures). Upon conclusion of internal control testing, the auditor will have either verified the initial control evaluation or identified conditions that require a revision of the initial evaluation.

Internal control testing will be followed by substantive testing. The extent of substantive testing will depend on the auditor’s (revised, if applicable) final evaluation of internal controls. Evidence acquired from performing substantive audit procedures, when considered in conjunction with the results of internal control testing, is a critical determinant as to whether an agency’s financial statements are free of material misstatements. Some important audit objectives of the testing phase are to:

To do this, the FAM model audit methodology includes guidance on the:

During Phase IV, the auditor considers the evidential result of testing tasks and other audit activities, completes a number of end-of-audit procedures, makes a final technical review of the audit procedures performed, and concludes whether sufficient evidential matter has been obtained to support the audit opinion and other assurances the auditor must provide on an agency’s financial statements and other information included in the auditor’s report.

Key audit tasks and procedures of this phase involve preparation of the auditor’s report on an agency’s:

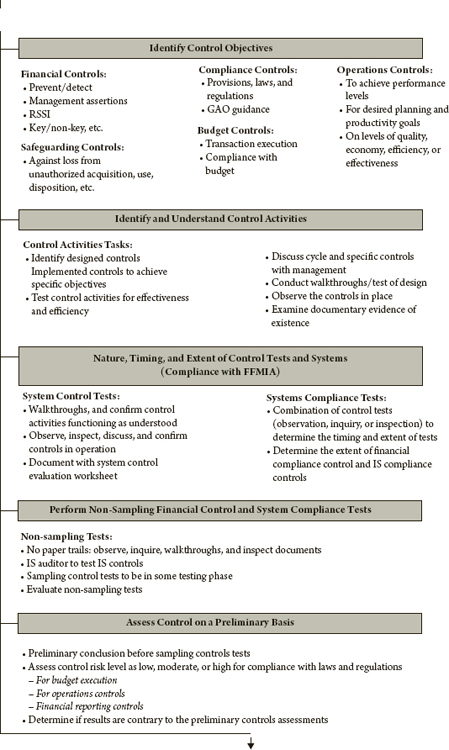

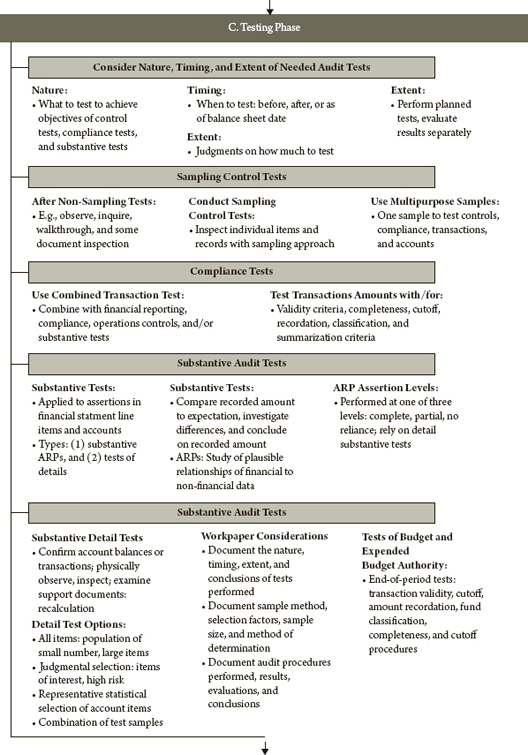

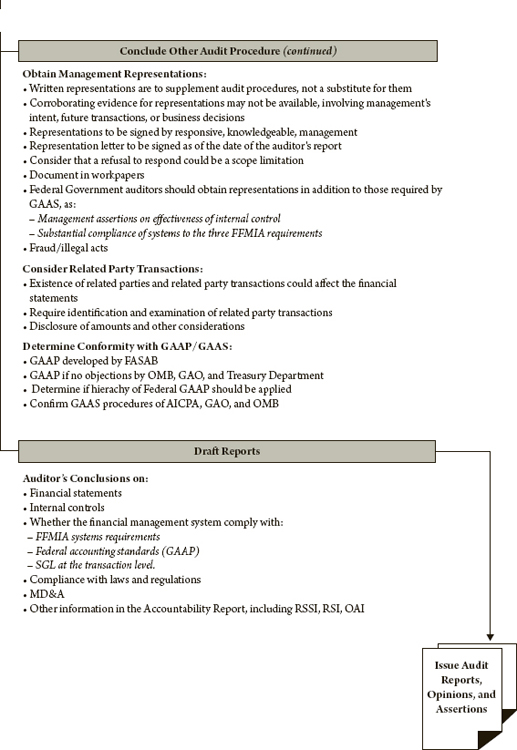

Exhibit 7.1 is an overview of the numerous audit tasks, activities, and audit procedures suggested by GAO and the PCIE in the FAM that should1 be performed for most Federal financial statement audits. Several of the following chapters contain additional discussions of some audit tasks and activities most often applied in practice. It is important to recognize that, in practice, an audit is a continuum of tasks and activities that must be completed within a finite budget and in a coordinated manner to permit the timely communication of the audit results to the government.

EXHIBIT 7.1 Federal Audit Model—Agency Financial Statements

The FAM and the execution of Federal audits are influenced by standards, concepts, guidelines, manuals, procedures, and techniques as well as specific circumstances encountered during the performance of the audit itself. These factors and their effect(s) on the audits of Federal entities are detailed in the following sections.

The Government Auditing Standards are not a stand-alone set of auditing standards. For prescribed audits, both GAGAS and GAAS of the AICPA must be applied for an audit to comply fully with the GAGAS criteria. Each revision of GAGAS contains references to the fact that GAGAS incorporates all of the AICPA’s GAAS and all the AICPA’s Statements on Auditing Standards, unless specifically exempted by GAO. Since the initial edition of GAGAS in 1972, GAO has not exempted an AICPA auditing standard. The beginnings of the Yellow Book can be traced to meetings as early as 1968 between state auditors and the Comptroller General at which the case was made to GAO that state and Federal auditing practices left much to be desired and that a unique body of auditing standards was needed to rectify this deficiency.

GAO’s audit and investigatory authority permitted audits and examinations to be made of Federal and non-Federal entities as well as Federal contractors, grantees, not-for-profits, educational institutions, and others receiving Federal financial assistance. Subsequent Federal legislation, particularly several laws passed in the 1990s, required that audits of Federal Agencies, programs, and activities conform to the Yellow Book. The standards are to be applied by any auditor, regardless of their employer, when these standards are required by Federal law, regulation, agreement, contract, grant, or Federal Governmental policy, including:

Further, GAGAS are not auditing standards imposed only on governmental entities. GAGAS are the auditing standards applied to audits of all Federal entities and non-Federal organizations that receive a designated level of Federal financial assistance, whether that assistance is obtained under a Federal contract or grant, loans or loan guarantees, Federal insurance programs, or Federal Government food commodity initiatives. With respect to the non-Federal entities, this universe of potential auditees includes organizations such as contractors, grantees, nonprofit organizations, colleges and universities, Indian tribal nations, public utilities and authorities, financial institutions, hospitals, and more.

The Yellow Book was initially promulgated by GAO in 1972 and has been revised and refined over the years. The December 2011 revision of the Yellow Book has incorporated all of the fieldwork audit and audit reporting standards and subsequent statements of auditing standards issued by the AICPA.

With the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in 2002 by Congress, the newly created Public Company Accounting and Oversight Board (PCAOB) became the legally empowered organization to set the auditing standards to be used by registered public accounting firms in preparing and issuing audit reports for publicly traded companies. When PCAOB promulgates these auditing standards, GAO has stated that it will monitor both the AICPA and PCAOB and clarify the GAGAS, as necessary.

Under the Federal audit model and its FAM, a condition precedent to forming an audit opinion on financial statements is that the auditor must first obtain and evaluate evidential matter concerning the fairness of several management assertions that are implicit or explicit in the agency’s financial statements and other reporting. Audits of financial statements, financial reports, and financial data provided by an agency’s management are a process of independently examining, assessing, and reporting on several assertions by that agency’s management with respect to evidence supporting underlying classes of financial transactions, individual accounts, account groupings, and line items in financial statements and other financial reports.

In presenting its financial statements, transactions, and accounts for audit, agency management explicitly and implicitly makes or warrants that several assertions are true with respect to the reported data. For example, an agency’s management assertions (as defined by the FAM) relate to:2

Thus, the auditor must determine, through the audit evidence obtained and examined for each class of financial transactions, individual accounts, account groupings, and line items in financial statement and other financial reports, whether these assertions are fair representations. Through audit tests and procedures, the auditor must examine evidence that supports or rebuts each of these assertions.

To obtain and evaluate evidential matter concerning the fairness of management assertions implicit or explicit in the agency’s financial statements and other reporting, the Federal audit model and its FAM require the auditor to employ or conduct a variety of audit procedures.

Some audit procedures are more appropriate for evaluating and testing controls; others are better suited to test the fairness of transactions, account balances, and account groupings. Also, various authorities have described and grouped audit procedures and tasks by different categories. A listing of commonly applied audit procedures, audit tasks, or audit activities, all of which are required at some time by the Federal audit model and its FAM, includes:

| Examine: | A reasonably detailed study by the auditor of documents or records to determine specific facts about the evidence |

| Scan: | A less detailed examination by the auditor of documents or records to determine whether there is something unusual that warrants further investigation |

| Read: | An examination by the auditor of written information to determine facts pertinent to the audit |

| Compute: | Calculation by the auditor, independent of the auditee |

| Recompute: | Recalculation by the auditor to determine the correctness of an auditee’s earlier calculation |

| Foot: | The addition of columns of numbers by the auditor to determine whether the total is the same as the client’s amounts |

| Trace: | The validation of details, as documents and transactions, in support of amounts recorded in ledger accounts and statements; a testing of details to summary data |

| Vouch: | The validation of transaction amounts recorded in ledger accounts and statements back to details, as underlying documents and supporting records; a testing of data from the summary back to details |

| Count: | A determination of assets or other items by the auditor through physical examination |

| Compare: | A comparison of information in two different locations by the auditor |

| Observe: | The personal witnessing of events, resources, or personnel behavior by the auditor |

| Inquiry: | Discussions or questioning by the auditor to obtain audit evidence |

| Confirm: | The receipt, by the auditor, of a written or oral response from an independent third party to verify information requested about the auditee by the auditor |

| Analytical review procedures: | The auditor’s evaluation of financial information by a study of plausible relationships among financial and nonfinancial data, involving comparison of recorded amounts to expectations developed by the auditor3 |

Generally, or with few exceptions, the auditor’s application or use of only one of these audit procedures to confirm or validate a particular management assertion would not be sufficient in itself. For the most part, more than one, and even several, of these procedures would be applied in a financial statement audit to confirm or validate a particular management assertion.

The determination of which audit procedure or combination of audit procedures should be employed by the auditor to most efficiently and effectively acquire necessary and sufficient audit evidence requires that decisions be made with respect to the timing, nature, and extent of the audit procedures required. These terms, used extensively throughout the FAM for a variety of testing and validation efforts, are generally defined in these ways:

In most instances, the FAM identifies the timing, nature, and type of audit procedures to be applied in the audit of a Federal financial statement. However, the Federal audit model and other models are somewhat less forthcoming with respect to prescribing the extent of, how much, or how many transactions, documents, actions, and events should be specifically tested. Decisions regarding the extent of testing are better left to the judgment of the auditor and the conditions and circumstances that the auditor encounters during the audit of a particular entity.

Audit evidence must pass several tests to be acceptable in support of an auditor’s conclusions and opinion. Such tests include relevance, validity, timeliness, lack of bias, objective compilation, and sufficiency. With respect to the sufficiency of audit evidence, this characteristic is judgmental and directly related to audit materiality, the adequacy of an agency’s systems of internal controls, and the conditions and circumstances encountered during the audit.

In large audit entities, such as Federal Agencies, evidence can be manually or electronically prepared or can be a combination of both data processes. Also, the evidence may have been compiled by the Federal Agency or outsourced to a contractor, or be a combination of both methods.

From an auditor’s perspective, the various types of audit evidence gathered can generally be categorized as:

The sheer size of Federal Agencies dictates that audit evidence be obtained through sampling in order to conduct an efficient audit. Thus, the Federal audit model and the Federal FAM describe both statistical and nonstatistical sampling, with considerable guidance being provided on statistical sampling approaches. Ultimately, the sampling approach must be dictated by the circumstances and conditions encountered in each audit. Both approaches do have their merits and demerits.

When performing the audit of an entity, examining a selected number of transactions, generally referred to as sampling, is by far the most common audit technique. Sampling can take any of several forms, including statistical, nonstatistical, and judgmental. These sampling forms are discussed in further detail in later chapters.

The scientific statistical approach, quantitatively based and premised on theory of probability, is best when applied to populations:

A subjective or judgmental sampling approach is premised on auditor expertise in relation to what may be considered an adequate or sufficient sample. Subjective sampling is most efficient when a relatively large portion of the universe can be tested through the review of a small number of transactions.

Materiality, a basic important audit concept, is a concern to an auditor from two viewpoints: (1) when assessing an auditee’s compliance with GAAP; and (2) when planning, conducting, and reporting the results of an audit made pursuant to generally accepted auditing standards and the Yellow Book.

Some standard setters have suggested specific dollar amounts, a percentage criteria, or specific conditions as being material. However, while these standards provide useful guidance, materiality remains a subjective concept requiring the exercise of auditor judgment in virtually every audit. Typically, these materiality issues warrant a separate examination, separate reporting, or different accounting and auditing emphasis, but these attempts to quantitatively proscribe materiality are admittedly arbitrary. In short, for accounting and auditing purposes, to be material, an item or issue must be significant, important, or big enough to make a difference.4

Financial statements can be materially misstated on two fronts: (1) for incorrect amounts and facts appearing in the statements, or (2) for amounts and facts that have been omitted from those statements. FASB’s definition of materiality (also cited by the AICPA, FASAB, and GAO) is:

Materiality: The magnitude of an omission or misstatement of an item in a financial report that in the light of surrounding circumstances, makes it probable that the judgment of a reasonable person relying on the information would have been changed or influenced by the inclusion or correction of the item. (FASB Concept Statement No. 2)

Materiality is not constant but relative, dependent on circumstances, and affected by the environment or industry within which the auditee operates. Amounts or factors material to the financial statements of one entity may not be material to another entity of a different size, with a different mission, or even for the same entity, but for two different fiscal periods. The concept of materiality is based on the premise that some amounts, matters, or issues, individually or in aggregate, are important enough to be fully disclosed and fairly presented in order for an entity’s statements to conform with GAAP. Implicit in this concept of materiality is that lesser amounts and other matters and issues are not as important and therefore are immaterial for the purpose of an audit.

The AICPA, in its guidance relating to materiality, states “the auditor’s determination of materiality is a matter of professional judgment and is affected by the auditor’s perception of the financial information needs of the users of the financial statements” (AU-C 320.4). Materiality, in this context, encompasses both a quantitative materiality (e.g., measured in absolute dollar amounts or percentage variances) and a qualitative materiality (e.g., an illegal payment, of minimal quantitative materiality, but that could have significant legal and ultimately large dollar consequences).

Materiality (of errors, misstatements, variances, changes, weak or overridden controls, etc.) is a concern in various phases of an audit and must be considered when:

For audits made in conformity with GAAS and audit opinions on whether the financial statements are presented fairly in accordance with GAAP, the auditor must consider the effects of material misstatements and material omissions, individually and in aggregate, that have not been corrected by the auditee.

References to when and to what preparers and auditors of financial statements must apply the materiality criteria permeate the Yellow Book. Some examples from the Yellow Book are listed next.

GAAS are rather specific in that auditors are instructed to conduct tests of controls, transactions, and account balances with the objective of detecting material quantitative misstatements. For audits involving governments and other public entities, often the qualitative issues emphasized by oversight boards and commissions create media focus.

Planning audit procedures with the objective of detecting material qualitative misstatements or material omissions in financial statements may not be cost beneficial or practical. Alternatively, GAAS instructs the auditor to consider qualitative factors that could cause seemingly quantitatively immaterial items to take on immense significance, or, in the language of GAAS, have qualitative materiality. Examples of qualitative issues having the potential to rise to a material quantitative matter might be noted or presumed instances of errors, illegal acts, fraud, thefts, misappropriation of funds and assets, defalcations, abuses, conflicts of interest, contract and grant terms, bond covenants, and the like.

AICPA members must justify departures from governmental GAAS, as defined and described in the AICPA’s auditing and accounting guidance for governmental entities. In the case of audits of governmental financial statements, Ethics Interpretation 501-3, Failure to Follow Standards and/or Procedures or Other Requirements in Governmental Audits, of the AICPA applies:

If a member [of the AICPA] . . . undertakes an obligation to follow specified government audit standards, guides, procedures, statutes, rules, and regulations in addition to generally accepted auditing standards, he or she is obligated to follow such requirements. Failure to do so is an act discreditable to the profession in violation of rule 501 [of the AICPA Code of Professional Conduct], unless the member discloses in his or her report the fact that such requirements were not followed and the reason therefore.

The AICPA’s GAAS describe measures of quality of audit performance, quality of exercised judgment during the audit, and the quality of audit objectives. In its many other promulgations for auditors, the AICPA continues to further define, describe, and illustrate these measures by delineating audit procedures, providing illustrations, suggesting audit programs, and offering guidance by many specific industries.

1 The Federal Financial Management Improvement Act of 1996 Congress required that “each agency shall implement and maintain financial management systems that comply substantially with 1) Federal financial management systems requirements, 2) applicable Federal accounting standards, and 3) the United States Government Standard General Ledger at the transaction level.”

2 The auditor may use these assertions or may express them differently, provided all the aspects of the assertions defined in AU-C 315.A114 are addressed (AU-C 315.A115).

3 Alvin Arens and James Loebbecke, Auditing: An Integrated Approach, 8th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1999).

4 See W. Holder, K. Shermann, and R. Wittington, “Materiality Considerations,” Journal of Accountancy (November 2003), for an excellent discussion of the importance of materiality considerations in financial reporting and auditing and the profound impact or complications arising from Financial Accounting Standards Board(FASB) 34, Capitalization of Interest Cost (issued 10/79) concerning the application of materiality to audits of governments.