The third standard of fieldwork states: “The auditor must obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence by performing audit procedures to afford a reasonable basis for an opinion regarding the financial statements under audit.”

Consistent with the audit model introduced earlier, during the internal control phase, the auditor must determine whether controls appear to be in place to provide reasonable assurance that the financial data to be reported on is fairly stated.1 Depending on the results of this evaluation, the auditor decides the extent to which controls are to be tested to provide the “sufficient appropriate audit evidence.”

This chapter expands on the internal control evaluation process introduced earlier and provides a controls risk assessment model that has proved useful in the execution of audits. This chapter concludes the discussion of the control phase of an audit that began in Chapter 9. An important output of this phase of the audit is expanding on the audit planning and programs developed earlier and deciding on an audit approach supported by detailed audit programs. The detailed audit programs guide the execution of both tests of internal control and the substantive testing of accounts balances.

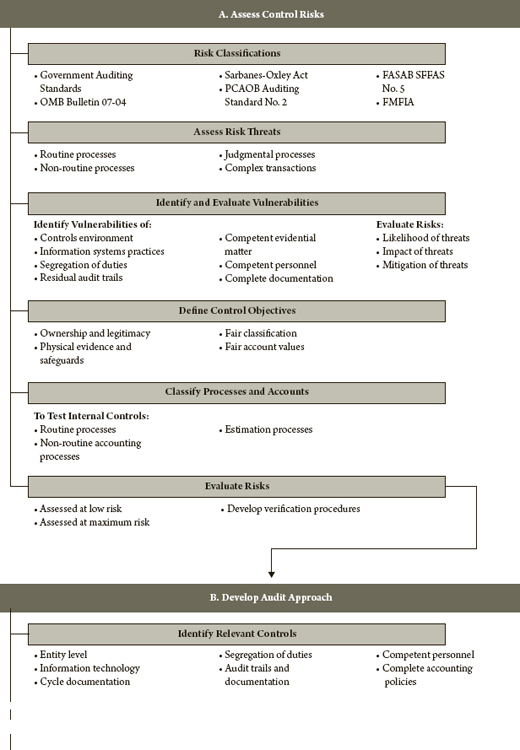

The auditor must formally assess control risks, that is, the risks that a material misstatement could occur in a financial statement assertion and not be prevented or detected on a timely basis by the system of internal control. In assessing control risks, the auditor is making an estimate of the relative effectiveness of the existing internal control system.

In assessing control risks, the auditor’s interest must be focused on the extent to which the government’s control system is preventing or detecting incomplete, inaccurate, or invalid transactions.

The Government Accountability Office’s (GAO’s) Financial Audit Manual (FAM) provides a practical template for assessing control risks by identifying three levels of such risks. The level of control risk is based on the auditor’s preliminary evaluation of internal control for each assertion, significant line item, and significant account. Based on his or her evaluation/belief, the auditor classifies control risks as:

Both GAO and American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) guidance provide that the auditor must document conclusions regarding assessed levels of control risks for each relevant system/cycle, group of transactions, and/or account balance. For audits in accordance with Government Auditing Standards (Yellow Book) standards, the auditor’s assessment should be documented in his or her planning documents and specifically the account risk analysis (ARA).

As a practical matter, a low risk determination usually requires more audit evidence supporting the presence of mitigating factors such as internal controls. This is not to say that a high risk determination need not be documented. In most, if not all, instances, a high risk determination relates to a control deficiency that must be reported to management and possibly to individuals charged with governance. Thus, a determination of high risk should not be arrived at lightly. The auditor must have facts well documented/verified to ensure not only audit efficiency but the avoidance of needless embarrassment.

Finally, during the execution of this phase, the auditor must remember that prior to testing, his or her assessment of risk is a preliminary estimate and subject to change if later tests disclose circumstances, conditions, and events indicating that the assessed level of risk was too low or that control deficiencies may have led to misstated financial statements.

In some circumstances, internal control deficiencies may be substantial, requiring the auditor to classify them as significant deficiencies or material weaknesses.

A deficiency in internal control exists when there is a condition in the design or operation of an agency’s system of internal control that allows misstatements to occur (e.g., allows transaction errors that cannot be prevented or detected by operating personnel in a timely manner). Substantial deficiencies are classified as significant deficiencies or material weaknesses depending on the magnitude of the deficiency.

The AICPA’s definitions for these conditions as set forth in. U.S. Auditing Standards—AICPA (Clarified) (AU-C) 265.07 appear next.

A material weakness is a deficiency or combination of deficiencies in internal control, such that there is a reasonable possibility that a material misstatement of the entity’s financial statements will not be prevented or detected and corrected on a timely basis.

A significant deficiency is a deficiency or a combination of deficiencies in internal control that is less severe than a material weakness, yet important enough to merit attention by those charged with governance.

GAO’s FAM (Section 580.32) adopts the AICPA’s concepts just discussed but provides for somewhat different definitions:

A material weakness is a significant deficiency, or combination of significant deficiencies, that results in more than a remote likelihood that a material misstatement of the financial statements will not be prevented or detected

A significant deficiency is a control deficiency, or combination of control deficiencies, that adversely affects the entity’s ability to initiate, authorize, record, process, or report financial data reliably in accordance with U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) such that there is more than a remote likelihood that a misstatement of the entity’s financial statements that is more than inconsequential will not be prevented or detected.

Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Bulletin 07-04, Audit Requirements for Federal Financial Statements (as amended in 2008), provides yet another variation on the same themes:

Material weakness is a significant deficiency, or combination of significant deficiencies, that result in a more than remote likelihood that a material misstatement of the financial statements will not be prevented or detected. This material weakness definition aligns with the same material weakness definition used by management to prepare an agency’s FMFIA [Federal Managers’ Financial Integrity Act of 1982] assurance statement. (Paragraph 2.11)

Significant deficiency is a deficiency in internal control, or a combination of deficiencies, that adversely affects the entity’s ability to initiate, authorize, record, process, or report financial data reliably in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles such that there is more than a remote likelihood that a misstatement of the entity’s financial statements that is more than inconsequential will not be prevented or detected. (Paragraph 2.13)

Auditors may choose which definition is easier to follow. Arguably, GAO and OMB definitions are easier to follow than the AICPA’s definitions. In more practical terms, if your audit conforms to any of the definitions just cited, you will be in compliance with all three standard-setting bodies.

OMB’s definition of internal control, as it relates to financial reporting, essentially parallels the AICPA’s definition. However, OMB adds as a specific objective of internal controls these details:

Compliance with Applicable Laws, Regulations, and Government-Wide Policies: Transactions are executed in accordance with laws governing the use of budget authority, Government-wide policies, laws identified by OMB, . . . and other laws and regulations that could have a direct and material effect on the Basic Statements.

The need to comply with laws and regulations, when noncompliance could materially affect the financial statements, is implied in the AICPA’s definition of internal control over financial reporting. However, OMB expands on the definition, in essence, by reserving the right to identify specific laws and regulations that should be supported by effective controls, thus removing the option for auditor judgment as to which laws and regulations will be tested.

A risk assessment is a thought-intensive judgment process requiring a careful consideration of documentation gathered earlier and the potential implications/effects of the processes, cycles, systems, or activities documented on internal control risks.

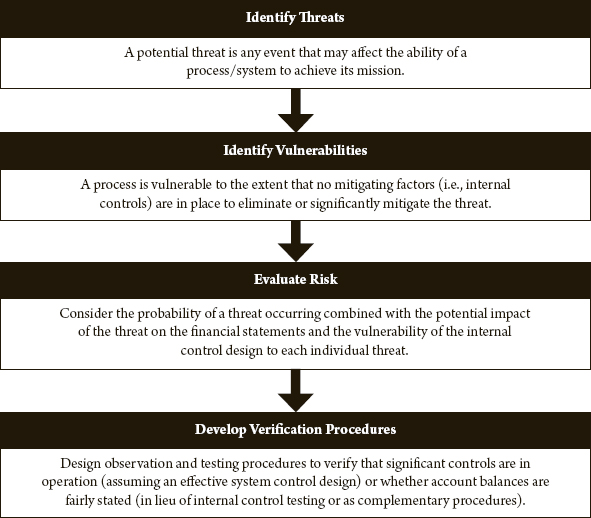

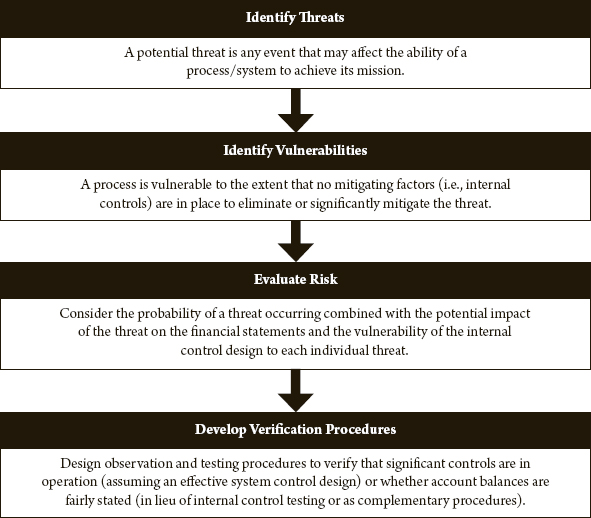

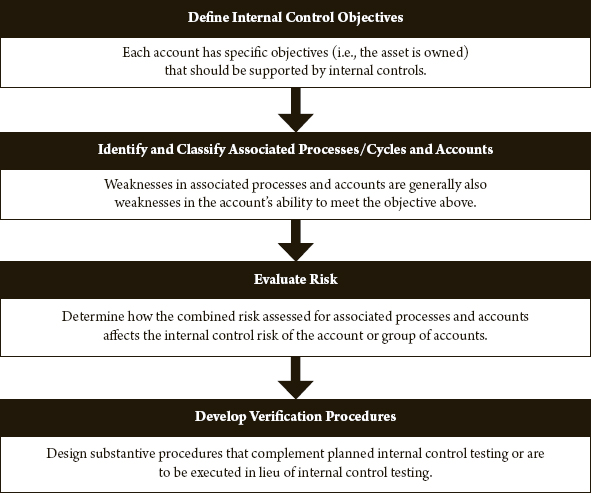

The risk assessment methodology discussed in this section is summarized in the following illustration.

The first three activities depicted in the graphic enable the auditor to define and document existing internal control risks, as required by AICPA and GAO guidance, and to develop an efficient audit approach that, where possible, capitalizes on existing system strengths (e.g., by testing controls) while focusing the auditor’s efforts on those areas that may not be supported by strong controls.

The model departs from a more traditional audit approach by addressing process or system threats instead of internal control objectives. This approach is strictly a judgment call. Experience dictates that the identification of threats (the flip side of objectives) focuses the auditor’s attention on the specific characteristics of the process/system being audited. All too often, identification of objectives becomes a recitation of good characteristics of any system that is the result of memorization and not the critical evaluation of the process or system. The model does not preclude the identification of objectives. As will be seen in connection with the audit of account balances where objectives are typically more diverse, our recommended approach combines the identification of threats and objectives.

The next discussion illustrates how risk assessments may be executed and includes techniques that have been found useful in the execution of financial statement audits.

Risk can never be eliminated, but with proper controls it can be reduced to a reasonable level. The initial effort in our assessment is to identify what can go wrong in the operation of a given process or system. It is important that threats be identified initially without considering whether controls are already in place. This practice reduces the possibility of threats being prematurely eliminated from consideration without a full evaluation of mitigating controls and knowing the full implications of the threat on the financial statements. Further, it enables a reevaluation of the threat when subsequent testing indicates that the mitigating control is not fully operational or effective.

The identification of threats requires equal parts imagination and experience. Extreme flights of fancy are not very productive, but neither is rigidity of thought. Risk assessments should be supervised by more senior members of the audit team but should also include contributions from more junior personnel. Experience is invaluable when it comes to the identification of threats, but sometimes it also hinders original thought. The identification of threats is facilitated by interactive discussions among audit team members with different levels of experience and assorted specializations. In identifying threats, the auditor will find the concepts of routine, nonroutine, and judgmental processes very useful. In general, the less routine and more judgmental the process is, the higher the level of risk and the number of possible threatening events.

The audit team meetings required by AU-C 315.11, Understanding the Entity and Its Environment, and AU-C 240.15, Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit, provide a good starting point regarding the identification of threats.

Having identified possible threats, the auditor considers whether the process includes procedures that eliminate or mitigate the threats (i.e., whether internal controls are in place that effectively reduce internal control risks to a reasonable or tolerable level). Representative general internal controls that the auditor considers include these:

In identifying internal controls, the auditor often refers to “best practices” as documented in formal checklists and other guidance. Virtually every auditing firm or agency has developed (or adopted) an internal control guide or checklist in one form or another. In addition, accounting and auditing literature is filled with such checklists. Some of the most comprehensive checklists can be found in GAO publications, including systems requirements checklists and the Internal Control Management and Evaluation Tool GAO-01-1008G (August 2001). There is, however, no substitute for audit judgment. As GAO stresses in every checklist or guidance issued, its documents are intended to serve as aids to auditors and managers, not as substitutes for independent judgment.

Auditors are cautioned to consider the real impact of each control. Too often, auditors assume that strong controls exist simply because of the existence of a procedure indicative of best practices. For example, a time sheet is one such best practice; however, its mere existence does not lessen the threat of phantom or nonexistent employees or prove that an employee actually worked the hours stated on the time sheet. Auditors must recognize that time sheets are but sheets of paper that anyone can complete. Without a requirement that time sheets be approved and/or reviewed by an appropriate member of management, there is no added assurance that an employee actually worked the hours stated on the time sheet. Further, without proper controls over authorization for the addition of new employees, including adequate segregation of duties of the approving manager, there is no assurance that the employee actually exists. In addition, without proper audit trails (i.e., approving signatures, properly controlled time stamps), auditors cannot test the control, although they may be able to observe compliance as part of a number of tests. Finally, in a poor internal control environment, the use of time sheets and the accompanying approval and audit trails could quite possibly provide no assurance that the threat has been mitigated.

By contrast, a process that is not supported by time sheets but that issues periodic and timely reports of payroll expense, including payee and hours worked, could be a significantly better internal control. This would be the case if the report were issued to a well-motivated manager operating in a strong internal control environment with proper segregation of duties.

The final determination of risk is generally based on the auditor’s assessment of these factors affecting each threat:

The combined consideration of the threat’s probability of occurrence, its potential impact, and the vulnerability of the process provides the basis for the auditor’s assessment of internal control risks (i.e., high, moderate, or low, following GAO’s classification).

During planning and the early activities of the internal control phase, the auditor identifies significant accounts or groups of accounts. As was the case with accounting processes/cycles, the auditor analyzes these accounts and evaluates the internal controls being applied by the agency. These accounts and groups of account evaluations are an extension of the risk assessment discussed earlier. Accounting cycles produce account balances by processing transactions, and the reliability of the account balance is affected by the internal controls associated with the accounting process/cycle or system.

Financial statements present data taken from account balances. Obviously, extending the risk assessment to include account balances is essential to obtaining competent evidential matter to support the auditor’s assertions. The account-level risk assessment typically follows the pattern shown next:

The first step in the evaluation consists of identifying the objectives (from a financial reporting perspective) of each account. The use of objectives to initiate the process instead of threats (as we did for processes/cycles) is a purely subjective one, but we believe that it is easier to relate an account objective to a financial statement assertion. In identifying objectives, the auditor may find it helpful to consider:

In this step of the assessment, the auditor identifies processes and accounts that affect the specific account being evaluated. In general, the auditor considers:

The auditor will have already identified and documented most processes/cycles associated with the account; however, each general ledger account is subject to other (usually nonroutine or estimation) procedures designed to ensure the fair presentation of the account balance. Typical examples of nonroutine and estimation procedures that are unique to an account or group of accounts are listed next.

It is possible that these processes were not identified with the more routine accounting cycles during the planning and early stages of the internal control phases. Thus, this step in the risk assessment process should ensure that all relevant processes are identified.

Finally, the auditor should be aware of the relationships between accounts, as weaknesses or misstatements in an associated account may impact the account under evaluation. Thus, for example, a loss loan reserve (usually the result of an estimation process) is affected by the accuracy of data related to the associated loans (e.g., account balance, aging, terms, etc.). Similarly, an accrued interest payable account is affected by the details of the associated debt payable account (e.g., balance, interest rate, maturities).

After defining the internal control objectives of the audited account and the related processes, the auditor will be in a position to establish whether these processes support the accomplishment of objectives identified. To the extent that the internal control risks of the associated processes were assessed as low, it may be possible simply to test relevant internal controls to support the auditor’s assertions without executing any complementary substantive procedures (or by performing only minimal substantive procedures, such as selected analytical procedures).

Conversely, where controls of the supporting processes were assessed as high, internal control testing may serve no purpose, and the audit of the account will require substantive auditing procedures to validate the account balance (or to ascertain the correct balance and propose audit adjustments). The development of an appropriate testing approach is discussed next.

Having completed the risk assessment, the auditor is in a position to develop audit testing procedures. As addressed next, the optimal testing approach must consider specific Federal requirements as well as audit efficiency.

The AICPA requires that an auditor obtain an understanding of internal control. It does not, however, require that the auditor test internal controls regardless of his or her evaluation of internal control risks. GAO requirements in this regard are similar. However, OMB Bulletin 07-04 guidance (not GAO Yellow Book standards) is more specific than either AICPA or GAO guidance. OMB guidance in Bulletin 07-04, paragraph 6.8, states, “For those internal controls that have been properly designed and placed in operation, the auditor will perform sufficient tests to support a low assessed level of control risks.”

Traditionally, AICPA guidance has stressed audit efficiency and allowed auditors to bypass internal control testing if other procedures were more practical or efficient in the auditors’ judgment. By contrast, both GAO and OMB have always emphasized the importance of internal controls because of the fiduciary nature of government operations.

In requiring the testing of internal controls even when internal control risks are below the maximum, OMB is simply asserting its belief that the public deserves reassurance that assets entrusted to Federal Agencies are properly safeguarded. Therefore, verifying that Federal systems are free of significant internal control deficiencies is an important consideration in the execution of annual audits of Federal Agencies.

It is interesting to note that while current AICPA guidance still does not require audit opinions on internal controls, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) of 2002 does require issuance of an auditor’s opinion on internal controls (as well as one on management’s representation on the adequacy of internal controls). Thus, in effect, at least for public companies, there is a requirement for control testing.

In developing the types of tests, an auditor must consider representative general internal controls, such as these:

General controls are important because, without them, there is little to be gained by testing more specific controls associated with each process/cycle. Although some general controls can be tested as part of a test of transactions (e.g., segregation of duties, presence of effective audit trails), many of the key controls, such as adequacy of documentation and availability of competent personnel, can be tested only through observation and the exercise of audit judgment.

After considering the effectiveness of general controls, the auditor proceeds to evaluate the individual controls affecting each subsystem/cycle and relevant to the audit assertions and significant accounts or groups of accounts. Auditors generally address these controls within each major process/cycle or application:

In addition, auditors look for the existence of more specific controls that meet the requirements of any given cycle. Thus, by way of example, in the case of processes and procedures related to accounts payable, auditors also determine whether sufficient controls are in place to achieve objectives such as:

In the case of revenue-related activities, auditors determine whether sufficient controls are in place to achieve objectives such as:

With the completion of these procedures, auditors are in a position to determine:

Based on the risk assessment, and within the constraints imposed by guidance, auditors develop an audit approach. Such an approach typically includes some or all of these tests:

Additional testing characteristics are discussed in the next chapter.

Upon completing the audit approach, auditors update, as necessary, update ARA and the audit strategy/audit plan developed in Phase II (i.e., the understanding of controls and evaluation of controls phase). In addition, the more senior members of the audit team must develop or update audit programs covering the tests of controls and substantive procedures to be performed in the testing phase of the audit. The design of an effective audit program is essential to the execution of an effective and efficient audit. A well-designed audit program enables the effective utilization of more junior personnel, supports the development of relevant audit documentation, and facilitates the monitoring of audit team members.

Exhibit 10.1 depicts the control risks process.

EXHIBIT 10.1 Assessing and Evaluating Internal Controls

1 The Government Accountability Office’s guide, Federal Information System Controls Audit Manual, is not an audit standard; its purpose is to: (1) inform financial auditors about computer-related controls and related audit issues so that they can better plan their work and integrate the work of information systems (IS) auditors with other aspects of the financial audit; and (2) provide guidance to IS auditors on the scope of issues that generally should be considered in any review of computer-related controls.