EXHIBIT 14.1 Overview of Performance Audit Process

Performance audits generally assess the efficiency and effectiveness of operations and programs. The objectives, purposes, and scope of such audits vary with the parties desiring a performance audit. Financial audits have the support of over 100 years of uniformity, documented precedent, precise guidance, and general acceptance. Performance audits, however, lack uniformity, have little precedent, minimal guidance, and, at times, lack auditee acceptance. Nonetheless, performance audits are valuable and are often demanded to answer important questions left unanswered by annual financial statement audits, particularly in the public sector.

While many assume that accountants “invented” performance auditing, this method of evaluation and analysis is practiced possibly to a greater degree in the social sciences and other disciplines. For years, nonaccountants have conducted scores of successful performance audits that blend the scientific research method (who, what, when, where, why, and how) with rigorous social research techniques and rather different data-gathering and documentation practices. Such approaches merge cross-disciplinary skills and practices, placing greater emphasis on current or contemplated activity and performance, in contrast to the historical emphasis of an accountant’s audit of financial statements.1

Observers not known for their public sector involvement have, without qualification, concluded that service institutions, such as governments, periodically need an organized audit of objectives and results in order to identify those entities no longer serving a purpose or that have proven the desired objectives are not attainable.2

For at least 100 years, formal recognition has concluded that audits of financial statements validating historical data have left unanswered questions about quality of operations, competitive status, competence of management and staff, and overall effectiveness of operations. Robert Montgomery, a leader in financial auditing (and founding partner of an original Big 8 accounting firm, Lybrand, Ross Brothers & Montgomery), called attention to the need for audits with considerably different scopes than standard financial statement audits of the early 1900s. He noted that other investigations or examinations were necessary to obtain information about the affairs of and to learn the truth about alleged fraudulent transactions, infringements, rights, arbitration, or values.3 In the 1980s, some attempted to distinguish between shades of performance-type audits. One separately defined management audits, operational audits, and performance audits in this manner:

In the 2000s, members of academe offered slightly different views of performance auditing. Operational auditing was defined as a subset of internal auditing (the other subsets being financial auditing, compliance auditing, and fraud auditing). Further, management auditing was cataloged as a subset of operational auditing, which attempted to measure the effectiveness and efficiency of an entity.4

Another contemporary view is that an operational audit is one that emphasizes effectiveness and efficiency and is concerned with operating performance oriented toward the future; financial audits, in contrast, are oriented to the past, with the emphasis on historical information. While operational audits are generally understood to deal with effectiveness and efficiency, there is less agreement with the use of the term than one might expect. Many prefer to use terms such as management auditing and performance auditing, while others do not distinguish between operational auditing, management auditing, and performance auditing.5

Of more relevance to managing and overseeing the activities of public bodies, especially those of the Federal Government, is the recent definition of performance auditing by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), appearing in the 2011 edition of its Government Auditing Standards (Yellow Book):

Performance audits provide findings or conclusions based on an evaluation of sufficient, appropriate evidence against criteria. Performance audits provide objective analysis to assist management and those charged with governance and oversight in using the information to improve program performance and operations, reduce costs, facilitate decision making by parties with responsibility to oversee or initiate corrective action, and contribute to public accountability.6

Because each performance audit has unique objectives, the scopes of such audits must be tailored to achieve those specific desires. Thus, these audits must be conducted in conformance with criteria other than those employed for financial audits. This flexibility makes performance audits powerful accountability and evaluation tools since audits can be structured in many different ways, depending on the need. For the most part, performance audits are the province of GAO, Federal Inspectors General, state and local auditors general, and governmental internal auditors. At times, however, independent accounting firms are retained under contract by a governmental entity to conduct performance audits.

More than any organization, GAO should be credited with broadening the focus of audits applied to governments, particularly the Federal Government. The need for an expanded audit focus was formalized in 1972, after extensive research, by GAO in its Yellow Book. The foreword of the 1981 edition of the Yellow Book noted:

Public officials, legislators, and private citizens want and need to know, not only whether Government funds are handled properly and in compliance with laws and regulations, but also whether Government organizations are achieving the purposes for which programs are authorized and funded, and are doing so economically and efficiently.

The foreword to the 2011 Yellow Book stated that the Federal Government’s audit standards “provide a framework for performing high-quality audit work with competence, integrity, objectivity, and independence to provide accountability to help improve Government operations and services.”

To this day, the Yellow Book provides the most definitive standards for the conduct of performance audits. These auditing standards appear in the 2011 edition:

The unique nature of performance audits dictates that each must be planned individually. By definition, each performance audit has different objectives, warranting different scopes of inquiry, requiring different audit skills, and resulting in a specially formatted report that is responsive to the specific audit objectives of only that performance audit.

Adherence to Government Auditing Standards is essential to ensure the credibility of individual auditors, the competence of the audit team, and the professionalism of their audit organization. Compliance with the general audit standards described in the Yellow Book is critical to the success of any audit. These general standards speak to topics such as these:

The general standards applicable to performance auditing are described next.

The first general standard Government Auditing Standards (GAS 3.02–3.59) pertains to independence:

In all matters relating to the audit work, the audit organization and the individual auditor, whether Government or public, must be independent.

This standard on independence is more specific than the comparable American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) standard. However, Statements on Auditing Standards (SAS), and additional AICPA guidance issued over the years require that members conform to essentially these same requirements. The 2011 GAO Yellow Book update also provides an extensive framework for assessing independence. Where a nongovernment auditor suffers from one or more of the cited independence impairments—personal, financial, external, or organizational—that auditor must decline to perform the work.

An auditor who is an employee of a government may not, due to legislative or other requirements, be able to decline to perform the audit. In this instance, the government employee must report the impairment(s) in the scope section of the audit report.

The second general standard (GAS 3.60−3.68) concerns professional judgment:

Professional judgment should be used in planning and performing audits and in reporting the results.

GAO requires the exercise of reasonable care and diligence, the highest degree of integrity, and objectivity in applying professional judgment. This standard imposes a responsibility on performance auditors to observe Government Auditing Standards and to describe, justify, and disclose any departures from these standards.

The third general standard (GAS 3.69–3.81) pertains to the collective competence of the audit team:

The staff assigned to perform the audit or attestation engagement should collectively possess adequate professional competence needed to address the audit objectives and perform the work in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards (GAGAS).

By this standard, the audit organization is responsible for ensuring that, collectively, the audit team has the knowledge, skills, and experience necessary to successfully complete the performance audit. Compliance with this standard requires audit organizations to have a process for recruiting, hiring, continuous development, and evaluation of staff to ensure a continuing workforce with adequate professional competence. For performance auditing, professional competence refers to the knowledge, skills, and experience of the assigned audit team, and not necessarily an individual auditor.

To conduct a performance audit, an audit organization may need to employ specialists, other than auditors, who are knowledgeable, skilled, or experienced in such areas as accounting, statistics, law, engineering, health and the medicines, information technology (IT), public administration, economics, social sciences, or actuarial science. Since performance audits often involve assessing program effectiveness, it is particularly important that the audit team include program experts. This standard ensures that auditors and their organizations are aware that training and proficiency as an auditor only will not be adequate for performance audits requiring knowledge and skills in other fields.

GAO’s interpretative guidance requires an audit staff to collectively possess the necessary technical knowledge, skills, and experience and be competent for the type of work being performed before beginning the audit.

The fourth general standard (GAS 3.82−3.107) pertains to quality control and assurance:

Each audit organization performing audits and/or attestation engagements in accordance with GAGAS must 1) establish and maintain a system of quality control that is designed to provide the audit organization with reasonable assurance that the organization and its personnel comply with professional standards and applicable legal and regulatory requirements, and 2) have an external peer review performed by reviewers independent of the audit organization being reviewed at least once every three years.

An appropriate internal quality control system encompasses the structure, operating policies, and procedures for monitoring, on an ongoing basis, whether the policies and procedures of an audit organization are suitably designed and are being effectively applied during each audit. The internal quality control system must be documented to permit evaluation and review to assess compliance.

To conform to this standard, audit organizations, both government and nongovernment, must have an external peer review of their auditing and attestation practice at least once every three years by reviewers independent of the audit organization.

Fieldwork audit standards provide guidance for the conduct of a performance audit in conformity with Government Auditing Standards and are discussed next.

The first fieldwork performance audit standard (GAS 6.0–6.12) pertains to planning performance audits:

Auditors must adequately plan and document the planning of the work necessary to address the audit objectives.

The plan for a performance audit should define, to the best detail possible, the audit objectives, scope, program performance criteria, and anticipated methodologies to be employed. Planning for a performance audit, even moreso than for a financial audit, is an iterative process that will continue to evolve over the duration of the audit. Planning for a performance audit is not a once-and-done task. The audit plan should be reduced to writing, becoming a part of the working papers and the audit evidence record.

The second fieldwork performance audit standard (GAS 6.53−6.55) pertains to supervision of performance audits:

Audit supervisors or those designated to supervise auditors must properly supervise audit staff.

The level and extent of supervision expected will vary in relation to the experience of individual team members. Those with less experience or who are new to the audit team would require more frequent monitoring. Evidence of supervision and review of teamwork should be documented in audit work papers.

The third fieldwork performance audit standard (GAS 6.56–6.59) concerns obtaining sufficient, appropriate evidence:

Auditors must obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for their findings and conclusions.

The quality, quantity, type, reliability, and validity of evidence are all relevant to the objectives of the specific performance audit and dependent on the judgment of the auditor. Categories of evidence suggested by GAO and considered in most performance audits include:

Evidence must be competent (i.e., valid, reliable, and consistent) with the facts reported by the audit team, which requires that the evidence be accurate, authoritative, timely, and authentic.

The fourth fieldwork performance audit standard (GAS 6.79−6.85) pertains to performance audit documentation:

Auditors must prepare audit documentation related to planning, conducting, and reporting for each audit. Auditors should prepare audit documentation in sufficient detail to enable an experienced auditor, having no previous connection to the audit, to understand from the audit documentation the nature, timing, extent, and results of audit procedures performed, the audit evidence obtained and its source and the conclusions reached, including evidence that supports the auditor’s significant judgments and conclusions.

The form, content, quantity, and type of documentation constitute the principal record of the work performed for the audit; aid auditors in conducting and supervising the audit; and allow for a review of audit quality. Evidence of supervisory review must exist in the audit’s work papers before the audit report is issued.

The reporting standards for a performance audit provide guidance to the auditor on reporting on performance in accordance with Government Auditing Standards. These reporting standards are discussed next.

The first reporting standard for performance (GAS 7.03–7.07) pertains to written audit reports:

Auditors must issue audit reports communicating the results of each completed performance audit.

A performance audit report must be written and appropriate for the report’s intended use.

The second reporting standard for performance (GAS 7.08−7.43) pertains to the content of audit reports:

Auditors should prepare audit reports that contain 1) the objectives, scope, and methodology of the audit; 2) the audit results, including findings, conclusions, and recommendations, as appropriate; 3) a statement about the auditors’ compliance with GAGAS; 4) a summary of the views of responsible officials; and 5) if applicable, the nature of any confidential or sensitive information omitted.

The auditor should ask legal counsel if publicly reporting certain information about potential fraud, illegal acts, violations of provisions or grant agreements, or abuse would compromise investigative or legal proceedings. Auditors should limit the extent of any public reporting to matters that would not compromise such proceedings, such as to information that is already part of the public record.

The third reporting standard for performance (GAS 7.44) concerns distributing audit reports:

Audit organizations in Government entities should distribute audit reports to those charged with governance, to the appropriate audited entity officials, and the appropriate oversight bodies or organizations requiring or arranging for the audits. The head of internal audit organization should communicate results to parties who can ensure that the results are given due consideration (in accordance with GAS and Institute of Internal Auditors’ Internal Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing). Public accounting firms contracted to perform an audit in accordance with GAGAS should clarify report distribution responsibilities with the engaging organization.

Internal auditors employed by governments should follow their audit entity’s own arrangements and statutory requirements for distribution.

In the Federal Government, GAO describes program (or performance) audits in two general categories:

This distinction of types of performance audits is clearer in the literature than in practice, wherein the relative economy, efficiency, and effectiveness are relative, interconnected, and at times not clearly distinguishable.

The uniform audit criteria and audit risks for financial statement audits are related to dollar significance or materiality. The criteria for performance audits is not nearly as simple. At times, those arranging for a performance audit are reluctant to, cannot, or will not define or formalize measurable criteria usable in planning a performance audit, yet a performance audit is demanded. The risk of defining acceptable performance often devolves to the audit organization.

Over the years, the AICPA and GAO, in their literature relating to performance auditing, have highlighted risks and other conditions that must be addressed in planning these types of audits. Some of these are listed next.

As is evident, the listed conditions and circumstances require that the auditor gains an understanding of audit expectations from the arranger(s) of the audit before commencing work. Failure to do so would result in the auditor assuming considerable risk. Arranger(s) of performance audits should examine, comment upon, and agree to the evaluation criteria to apply throughout the performance audit. This cautionary measure could potentially preclude the auditee from later protesting that the performance criteria and achievement factors evaluated were made up by the auditor and are neither relevant nor intended by the program’s legislation.

Chapter 6 of Government Auditing Standards contains advice and guidance to assist in the development of program performance criteria, a methodology for implying or inferring creditable, appropriate, and relevant performance criteria when possibly none was identified in law. This source should be consulted when drafting the audit program and determining the audit procedures to be applied.

Over 40 years ago, GAO, in its earliest guidance, noted that performance audits may be conducted in uncertain environments, can have different scopes of examination, and may require audit procedures different from those used in the more common financial audits, and that the audit report may require unique tailoring to each specific audit.7 It is important to keep in mind that because of the flexibility in the way performance audits can be planned, they are powerful tools that provide constructive oversight to improve overall management. Nonetheless, GAO outlined a process that could be applied to a performance audit, review, evaluation, or whatever title is used to describe an examination process to assure that the audit is properly planned, professionally performed, and objectively reported.

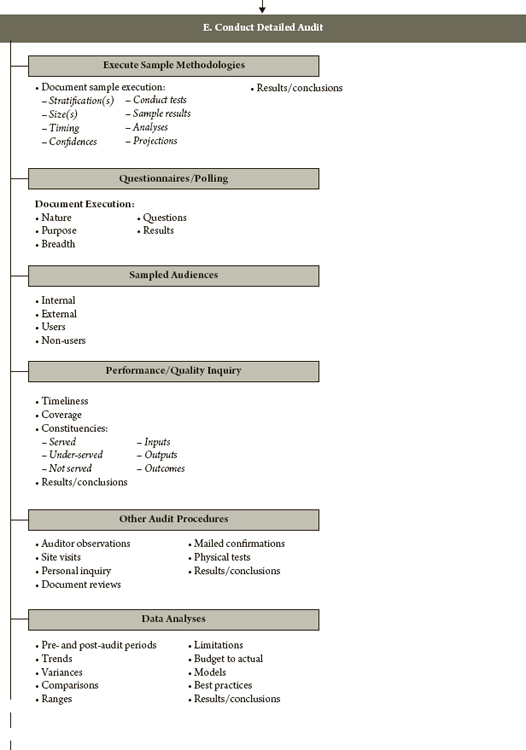

Exhibit 14.1 is a partial listing of considerations to take into account when planning a performance audit that must conform to criteria of Government Auditing Standards.

EXHIBIT 14.1 Overview of Performance Audit Process

The appropriateness, sequencing, and listed phases and tasks must be assessed in relation to the conditions or circumstances of each auditee and program to be audited. Note that there is a general scope of audit work that must be completed, a methodology that must be applied, and an objective, factually based report that must be submitted to the arrangers of the audit.

The following sections provide an overview of that GAO guidance, some of which exists in GAO’s current edition of Government Auditing Standards.

Performance audits should not be viewed as necessarily critical or negative. These audits could be beneficially made to identify issues of increased staffing, modernize the equipment plant, or design new management approaches that might be required to significantly expand services and benefits to multiple locations or to several other programs. As early as practicable, the auditor should convene separate orientation conferences with (1) arranger(s) of the audit and (2) auditee management and key staff. The purpose, process, timing, and operating protocols to be applied in the audit must be discussed. The nature of the performance that is to be examined or reviewed should be described to the auditee and alternatives and critical comments seriously examined, before the auditor proceeds to the detailed planning phase.

GAO’s suggested approach is to conduct a survey at the outset to assess, on a preliminary basis, whether the facts appear consistent with opinions, views, and comments provided earlier by the arranger(s) of the audit and auditee management. The tasks in this phase are directed toward acquiring, as quickly as possible, a historical perspective about the program; its constituents, issues, and accomplishments; extent of computerization; and knowledge of the financial, operational, and other data systems designed to support the program’s management and accountability needs.

GAO described the survey as a short-duration, fast information-gathering phase; no real attempt is made to assess or audit the veracity of information provided by the auditee. While problem exploration or deficiency identification may occur, the emphasis is not on doing this. Alternatively, the purpose of the survey is to further enhance background provided to the auditor and assist him or her in understanding the program activities, services, functions, and constituents, each of which will be examined in greater detail as the audit progresses.

Depending on the nature of the desired performance audit, data needs could arise relative to these areas and more:

The typical historical accounting system will not be fully responsive to the data needs of a performance audit. While a management information system might have some of these data, almost no governmental program’s system can address the full range of potential questions that could arise or be of concern.

The creation of an ad hoc database(s) is a precedent condition to planning a performance audit. As early as possible, efforts should be made to identify where there is a shortage of information with respect to the questions and inquiries to be made in the audit. To a greater or lesser extent, an ad hoc database(s) must be implemented, and will include design, drafting, and printing of data collection forms (e.g., form for surveys, polls, auditee-completed questionnaires, mailed confirmations, auditor-prepared inquiry forms, spreadsheets, etc.). In addition, software programs will be needed to input, process, and assist in analyzing collected data. Time devoted at the outset of the audit to brainstorming will be well spent.

GAO contrasts its suggested review phase with the preceding survey phase by the depth and specificity of inquiries. Also, the perceived program issues, problems, deficiencies, and levels of achievement may turn out to be incorrect or not relatively significant, but other more serious matters may arise or be disclosed that require a change of audit focus. Further, no budget would ever permit a comprehensive audit of everything. Choices must be made regarding what is to be examined, and audit focus must change as gathered facts change perceptions. Substantial, high-risk issues may require an audit of considerably greater depth than earlier planned; lesser, lower-risk issues may need to be dropped from further examination.

For these reasons and others, the objective of the preliminary review phase is to permit an informed basis for winnowing down the audit scope and focusing on the most essential, important, critical, or problematic matters and those of highest priority. Early tests must be made of known or derived performance indicators, with recognition that some known indicators may be inadequate and that other, better indicators may be needed. During the review phase, a more complete inventory will be made to confirm the skills and experiences required to competently examine the key issues and complete an assessment of the program. This phase is where more definitive conclusions must be reached concerning the relevancy, currency, accuracy, adequacy, and effectiveness of the auditee’s systems controls, accounting, and reporting (e.g., financial, operations, and management information systems). The development of specific audit programs and listing of detailed procedures that must be completed to gather, examine, compile, synthesize, and analyze evidentiary materials should also be completed during this phase. A concluding effort of the review phase must be the refinement or revision of the preliminary audit plan.

The detailed audit phase is concerned with obtaining facts to confirm or refute earlier hypotheses, perceptions relative to program achievement, outputs and outcomes, and issues or problems and to gather evidence to permit conclusions on the operational economy, efficiency, effectiveness, and “faithfulness” of program performance and attainment of reported program results.

Getting the facts results from applying a variety of survey and auditing techniques, which GAO suggests could include, among others:

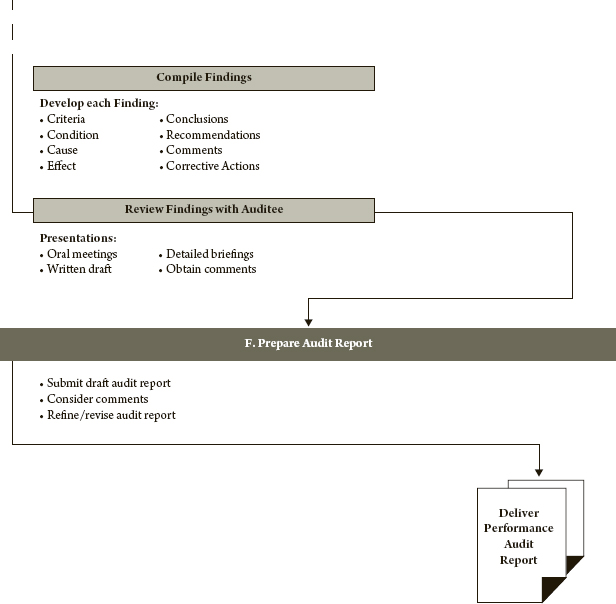

The end game of the performance audit is to identify, develop, document, and report audit findings. A finding is defined in the Yellow Book as:

The result of information development—a logical pulling together of information to arrive at conclusions about an organization, program, activity, function, condition, or other matter that was analyzed or evaluated.

Care must be taken in any audit to ensure that the audit team does not fall victim to the perfect vision of hindsight. The Yellow Book includes a technique requiring critical examination of the audit evidence gathered in support of what is described by GAO as the several elements of each or any audit finding:

The performance audit report should clearly and objectively report or comment on each of these elements for each reported finding.

Government Auditing Standards do not prescribe a specific form for the audit report but require that the audit report include:

a description of audit objectives and the scope and methodology used for addressing the audit objectives.

As soon as practicable, and if permitted by those arranging for the performance audit, information on these report content items should be provided to the auditee:

The protocol for presenting audit findings to the auditee will vary and may even be defined by the arranger(s) of the audit. If permitted by the arrangers, the reporting of results of a performance audit might include an overview oral, written, or PowerPoint presentation. A written draft of each finding may be provided to the auditee with a request for auditee comments, preferably in writing. Following assessment of auditee comments and reconsideration of certain contested issues, a final audit report should be prepared and submitted to the auditee, and the final written views of the auditee will be considered.

Auditors cannot ignore the axiom: Facts not reported cannot be evaluated by readers or users of the audit report. Performance audit reports should provide sufficient information and facts to stand alone, unaided by additional oral or written supplemental testimony or explanations. A performance audit report should be sufficiently complete, in and of itself, to permit a user or reader of the report to audit the auditor.

1 Frank L. Greathouse and Mark Funkhouser, “Audit Standards and Performance Auditing in State Government,” Government Accountants Journal (Winter 1987–1988): 56–60.

2 Peter F. Drucker, Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices (New York: Harper & Row, 1973), Chapter 14.

3 Robert Montgomery, Auditing Theory and Practice (New York: Ronald Press Company, 1934), p. 647.

4 Larry F. Konrath, Auditing: A Risk Analysis Approach, 5th ed. (Independence, KY: Southwestern, 2001), p. 669.

5 Alvin Arens and James Loebbbecke, Auditing: An Integrated Approach, 8th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2000), p. 797.

6 Government Accountability Office, Government Auditing Standards, 2011.

7 Government Accountability Office, Comprehensive Approach for Planning and Conducting a Program Results Review, 1973.