chapter 5

She was a funny woman [always cheerful and laughing]. I laugh with her. I walked across one time. “I got some news for you,” she said. “What news?” “My bedroom is now delivery room,” she tol’ me. “All animals go in there to have babies.”

—Elaine Dester

The goats did fairly well. The buck I got last year is related to so many of my does he will be used on his non-relatives and then get turned into feed for the mutts and chooks. I had two singles, one quads, three triplets and three twins. The quads are three does and a buck. They are all so comical and all characters. The buck . . . father of the quads . . . came from the local judge—C.C. Barnett. Locally the buck is called “Judge, you stinker.”

The neighbour hauls our mail and groceries etc. My truck is visible but unmoveable; besides we’re snowed in . . .

—Extract from a letter

from Ginty to Hilda Thomas

We would bring Ginty’s mail from the Kleena Kleene post office. Ginty accused us of damaging it. She told the post man to initial any tears on the envelopes. At that time you could cross the river on a logjam. People with good balance could walk. People like me had to crawl.

—Leslie Lamb

It would not take a lot more snow to block the telegraph road again and I wanted to ask Ken and Leslie if I could leave my vehicle parked across the river in their yard. Ken would keep his road open with his tractor. Rather than drive around, I thought I would try and cross the river on skis. It was pretty much frozen over although very lumpy and bumpy. It shouldn’t be that deep even if I did fall in, but the current was swift and there would likely be ice along the bottom. If I broke through, there would be a good chance that I would lose my footing.

The dogs had been visiting back and forth across the ice. There was a snow-covered lump of something on a gravel bar—probably a bit of fallen bank—and this was completely yellow. My dogs would go and pee on it; then Ken’s dogs would come and pee on the other side. A well-packed trail of paw prints crossed the river nearby. When I approached, I could hear water gurgling below but it seemed to be as good a place as any and I shuffled across. I floundered through a belt of cottonwoods and alders, followed moose tracks to a low place in the fence, then trudged through the field to Ken and Leslie’s house. “Sure,” Ken said. “No problem leaving the van here. Ginty used to put her vehicle in our yard in the winter. She had her mail delivered here when they used to drop it off at the end of our driveway.”

I retraced my tracks and just as the tip of my skis touched the spot where water ran below the ice, there was a crack and a long hiss, and a whole section of river caved in. That had happened to me once before near Nuk Tessli. There, I had been on snowshoes; I had crossed the river with some concern but no problem, had gone to a nearby trap cabin where I was going to spend the night, then came back with a billycan to fetch water. The minute my snowshoes had touched the edge of the river, even though all my weight was still on the shore, in crashed the ice. There, I could avoid crossing the river again. Here the only alternative was an eight-kilometre walk. With my heart in my mouth I chose a different spot and crept over. Perhaps the river would be safer later in the winter, but leaving my van at Ken and Leslie’s was not going to be an option at this time.

The new year had been ushered in by rain. The sky cleared for the night of January 3 and the full moon was profoundly brilliant, shining on my face through the bay window and making the snowy landscape glow with ethereal light. For a day or two we had blinding sunshine but it was very mild and the snow was glazed in the morning and wet and sticky by the afternoon. More snow fell. I thought I had better see if I could still drive the telegraph road. Thirty centimetres of snow had fallen on it since it had been ploughed, almost half of that since I had last driven on it. I threw an axe, shovel, rope, come-along, toboggan and snowshoes into the van just in case. Once again the vehicle amazed me. It slithered and slewed and bottomed out the whole distance but kept clawing its way along. And it didn’t even have chains or winter tires. But on January 8 it snowed another five centimetres. I doubted I would be able to drive the road again.

About two-thirds of the way along the telegraph road is a Y-shaped junction. A further four kilometres along the other branch is a property owned by a man who lives in the Bella Coola Valley. The cabin on this property burned down but he still runs horses there and likes to visit once or twice in winter to bring bales of hay. His road had never been ploughed at all and Rosemary, in our email correspondence, told me that Neil Griffith was going to plough him out and we could share the cost as far as the Y. This seemed an attractive proposition.

I had met Edgar a couple of times on the telegraph road. He was a shortish man, around my age, who wore his straggling greying hair shoulder length and sported thickly knitted handspun sweaters and hats somewhat the worst for wear. He had a strong US accent. It was not in his nature to make friends, but I rarely saw him and he smiled at me as much as he scowled. Rumours abounded about him, the most common of which was that he was actually very wealthy, was the black sheep of the family, and that when his family company in Silicon Valley required a signature on a document they flew up in a helicopter to get him to sign it. I took all this with a grain of salt: I was once told that when I first came into the country to start Nuk Tessli, some locals (men of course) decided that as I was a single female, I was building the remote resort in the mountains to have wilderness sex orgies. Anyone who is a little different . . . and yet everyone who lives on the Chilcotin develops individualistic traits. Whether they are odd because the country has shaped them or gravitate here because they were misfits elsewhere is a moot point.

Rosemary kept in touch with Neil by phone and passed the information to me by email. She first told me to expect Neil on January 10 but his Cat broke down. This was fortuitous, because later that day it started to snow in earnest and it continued for twenty-four hours. Everything was drowned in snow. My van was a white mound with two black wing mirrors sticking out like ears.

The van and the cabin in the Big Snow.

Belly-deep moose track.

Through the kitchen window the wall of snow that had dumped off the roof had nearly joined the eaves. I took the tape measure to the chopping block, which had been bare before this latest dump started. The tape recorded another fifty fresh centimetres. I slogged outside on skis and snowshoes. The total pack would have been chest high if I could have stood on the ground. This was more than triple the usual fall for the area. Moose were plentiful; their belly-deep tracks ploughed ditches through the snow. They could step over the fences without knocking snow off the top rails. The little trailer by the river was half buried. That night, the sky cleared and the temperature bombed to -36°C.

I was put to the bottom of the ploughing list. First Neil had to dig himself out. Then there was a score of people whose pickups and tractors could make no headway in this; they had to wait until a bigger machine was available. There was so much work to do but the snow was so beautiful I allowed myself some time off to explore. I broke ski trails to the south and the north, finding myself both times on high bluffs with gorgeous views of the mountains and the wild, snow-clogged river below. I skied to the upper place. The creek through the ponds and fields was roaring within its cocoon of ice. It was officially called after Ginty but using her real name, Nedra. I know that is how she was christened because there was an abandoned credit card in the Packrat Palace. Nedra Jane Paul. No one can tell me why she was called Ginty.

During this time, Ken and Leslie emailed me an invitation for lunch. They had a buyer for their place and were preparing to leave; there would not be many more chances for me to get details of their relationship with Ginty. I was still waiting to be ploughed out, so the only way I was going to get there was by crossing the river again. The ice would likely be a little more stable by now. Still, it was with great trepidation that I shuffled my way across. The new deep snow was soft and fluffy. On the far side, in the bush, even with skis on, it was thigh deep. Latching onto a convenient moose track, I found the best way to cross Ken’s fence—like the moose I could step over easily. I did not have to take off the skis.

When I first bought the place, Ken and Leslie had given me documents pertaining to the land. The first was the initial survey, whose scale was twenty chains to one inch. The part I now inhabited, the triangle fronted by the river, had once been the northeast corner of a quarter section whose opposite corner was buried in the lake on the far side of the highway from me, but when I looked at the document I was confused. There was the river, although its course had changed a bit, and two branches were indicated instead of one, and there was the lake, but the highway in between did not seem to be marked. Then I saw the date below the backward-sloping copperplate signature of the surveyor in the bottom right corner: “Dec 1909.” Highway 20 did not exist in this part of the Chilcotin then. It was not completed until 1953, although the section past the lake would have been driveable (more or less) by the 1930s. A finely dotted line wavered up from the south corner of the map and ended in the middle of the plan. The line was labelled Chilcotin Trail. A later hand had added crude dashes further west and written Approximate Bella Coola Highway and added an arrow at the top: “Bella Coola Approx 100 MI,” and at the bottom: “Williams Lake Approx 165 MI.”

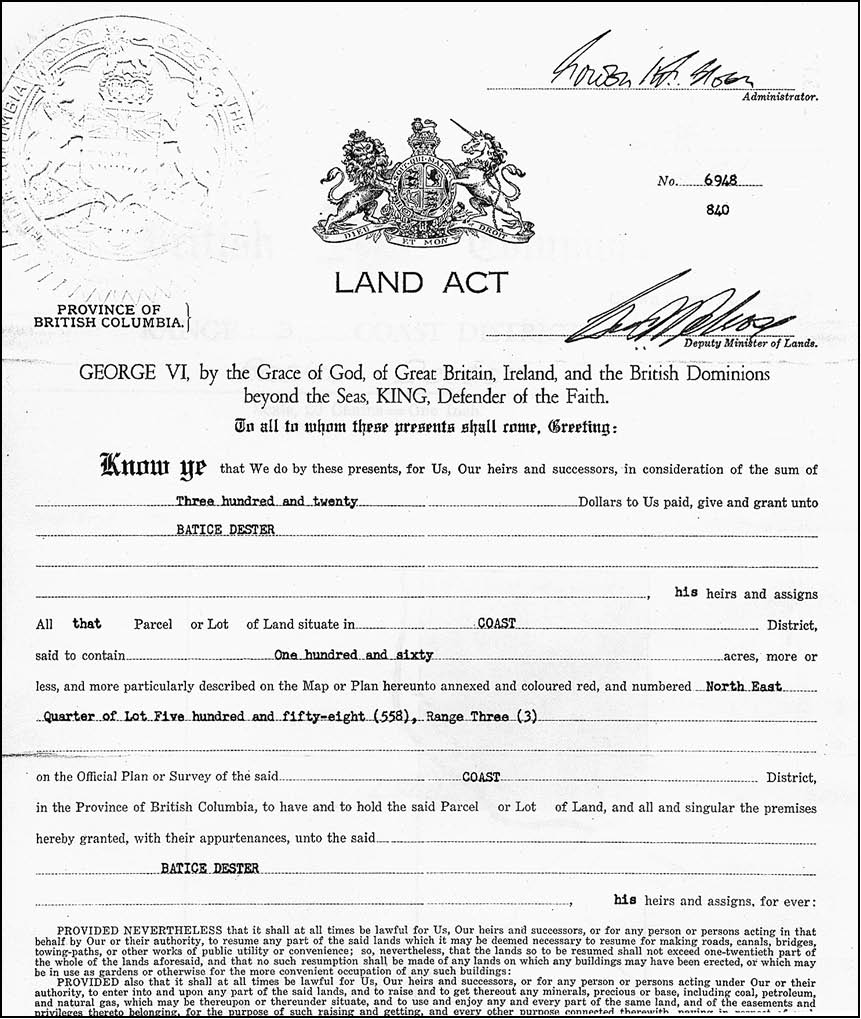

The second dated document was part of the Land Act.

GEORGE VI, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, Ireland, and the British Dominions

beyond the Seas, KING, Defender of the Faith

On all to whom these presents shall come, Greeting:

Know ye that We do by these presents, for Us, Our heirs and successors, in consideration of the sum of Three hundred and twenty Dollars to Us paid, give and grant unto

BATICE* DESTER, his heirs and assigns

All that Parcel of Lot of Land situated in COAST District, said to contain One hundred and sixty acres, more or less, and more particularly described . . . and numbered North East Quarter of Lot Five hundred and fifty-eight (558), Range Three (3) . . . hereby granted, with their appurtenances, unto the said BATICE DESTER, his heirs and assigns for ever: . . .

It was signed on

this Eighth day of November, in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and Forty Nine and in the Thirteenth year of Our Reign.

The map accompanying this piece of paper showed only the west branch of the river, which is now no more than a slough, thanks to the heaps of gravel that have been bulldozed to block it off. (This, of course, is why the river is eating into my property.) Adrian Paul took over the tract north of the river on March 1, 1951. For whatever reason, it is his daughter’s name that appeared on the deed. In 1959, Ginty signed another land agreement, this time with “Elizabeth the Second, in the sixth year of her Reign, for the adjoining Lot One Thousand Six Hundred and Eighty-Eight (1688), said to contain Forty acres more or less, in consideration of the sum of Sixty dollars.” She wanted this property solely for the water rights. Even then it was cheap. It was probably considered useless to anyone else. Surrounding both properties were “Vacant Crown Lands.”

Part of the original deed to Ginty Creek.

This was a notice in the Victoria Colonist of November 21, 1919:

Lt WAB Paul, together w/wife and infant child returned to Victoria from Eng. He left here w/30th Bn 1915, served in Fra and was given a commission in Imperial Forces. WIA twice, the 2nd time, in 1917, he was taken POW and it was not until 1918 that he was repatriated. Mrs. Paul, formerly Miss RA Thomas of Victoria, went overseas to offer her services as VAD, and served at St Thomas Hosp, London.

The infant child was most likely Ginty’s brother. Ginty herself was born in Victoria, probably in 1920. Like so many pensioned ex-service men, Mr. Paul became a chicken farmer. This was on Vancouver Island near Comox.

Ten years later, the government asked those who did not need their army pension to forgo it. Adrian was well enough off and did so; he sold his farm, left his wife and children in Victoria, and came north along the coast as a surveyor. He worked inland from Bella Coola first (there was no road to the interior then) but eventually came up to the Chilcotin. He built a rough cabin in the bush somewhere, but then moved to the stone pump house, which is now one of the few remaining buildings at Puntzi Mountain Air Base. He phoned the weather in every day but also got a job as a linesman for the telegraph line.

Puntzi had been built in 1953 for the US Air Force as a radar site to track invading aircraft. It was turned over to the Canadian Air Force in the early 1960s, then closed a few years later. There is not much left of it now, but the long runway is used for fighter aircraft practice for a few weeks each year, and for water bombers if they are needed during the fire season. The weather station has been maintained, although all the data are recorded automatically now. Puntzi is a high, bleak place, with little protection from the north, and has on more than one occasion reported the coldest temperature in Canada.

Although Ginty Creek had been surveyed in 1906, no one had lived there until Adrian arrived. Ginty would come up for visits during her school vacations. After she became a teacher, she mostly lived where she worked, which was all over BC. She was never in one place for more than a year or two. Adrian was already an old man when Ginty inherited money and came to stay. “That wasn’t too long before we arrived,” said Ken. “When we were looking for property I stayed the night in a cabin that was on the knoll next to where you have built. That was in 1976. The cabin had been built by some awfully English friends of Ginty’s. It was in a disgusting mess when we took over the place in the early ’90s, missing half the roof, full of junk, and riddled with packrats. So we pulled it down and hauled everything to the dump.

“Ginty and her father were living in a tarpaper shack when I stayed there. There was no Packrat Palace then. The cabin was tinier than yours but had three rooms—an entryway, a living room and kitchen, and a bedroom. When Ginty moved in full time she got the bedroom and Adrian slept on a cot in the kitchen. On one occasion I went over for lunch. Some people arrived and Ginty and her father went outside to talk to them. While I was sitting there, a goat ran in and slurped the dregs in all the teacups.

“They planned to build a bigger cabin and got hold of Batiste and his son Mack Dester to do it. They were both pretty good builders. A lot of their structures are still standing. The new house of Ginty’s was supposed to be two stories—a basement and a log upper floor—but in the morning Adrian would tell them one thing and in the afternoon Ginty would say something else so the Desters quit. When Adrian died, Ginty destroyed what there was of that building and found someone else to build the wannabe lodge.”

“We started our own house in 1977,” Leslie told me. “I was also a teacher by then. While we were building, we had relatives come and help us. Ginty crossed the river on the logjam and told us I was not feeding everyone properly. She went back and brought us a chicken. Only problem was, it was still alive. Just what I needed, having to pluck and gut a chicken when I was so busy.

“It was not long before we were in Ginty’s bad books,” Leslie added. “I asked a neighbour why she thought that would be. She said Ginty was like that with everyone. ‘You were getting the brunt of it because you were the closest,’ she said.”

“Email me when you get home,” Leslie admonished as I set off back across the river. Should I use the same crossing or would it collapse? I decided to try a different route and got over without mishap, but it was too nerve-wracking for me to continue doing it. Either the winters used to be colder or Ginty was built of sterner stuff than me. Leaving my vehicle in Ken and Leslie’s yard was not going to be an option as far as I was concerned.

Rosemary emailed me and told me to expect Neil, the man with the snowplough, to come on January 16. It was -22°C. I warmed up the motor of the van so I could move it easily when he came. I waited all day. On the morning of the 17th I thought I heard voices and a car door slam, but nothing happened so I figured it must have been people on the highway. It was -25°C. I switched on the van again for a while. And then it came. A huge, beat-up old Cat that had once been a colour I had heard a farmer describe very aptly as “calf-shit yellow.” The big blade on front pushed a mountain of snow. I once spent a summer in Cambridge Bay in Canada’s central Arctic. At the end of August the icebreaker came, forging a way for the barge bringing the community’s supplies for the year. That’s what it felt like when Neil’s ponderous behemoth hove into view.

It had taken him six hours to reach the Y the day before. Edgar had followed him but Neil had been unable to go further. Edgar had spent the night in his truck at the Y. “Why didn’t he come here?” I asked. Neil shrugged. Edgar was like that.

Slowly the yard was cleared and I dug out the van and moved it. Neil came in for coffee. He was a squat, strong man with icicles in his beard. The Cat had an open cab with no weather protection. His handshake was icy and, once indoors, his face turned such a vivid red I was alarmed for his health.

By early afternoon I could drive out between the walls of snow to the post office and store. I had not picked up mail since before Christmas and I had been reduced, for several days, to reading by the light of a single candle. For some years friends have been sending me The Globe and Mail’s cryptic crosswords. The print is small and I was having a hard time reading the clues. At Nimpo and Anahim I stripped the stores of their emergency candle supply.

It was dark when I returned. Neil’s flatdeck was parked at the turnoff from the highway and I hoped I would not meet him on the telegraph road as there would be no room to pass. As I slowed to turn, I was surprised to see someone materialize out of the darkness. Neil flagged me down. “You can’t get through,” he said. “But how do I get home?” I wailed. “Just temporary,” he explained. “I ran out of fuel about a kilometre in. A friend’s bringing some. Should only be about fifteen minutes.” We stood outside in the cold and waited. Neil’s cigarette glowed red in the dark.

A pickup arrived and the two men disappeared. They seemed to be gone a long time. Eventually an alien light began to pick out the trees, and the machine lumbered into view like a yellow-eyed dinosaur. Neil still hadn’t got all the way to Edgar’s. He would finish the job the following day; presumably Edgar was spending another night in his truck. By the time I reached my cabin, it was snowing again.

* Although the name “Batice” is on the official document, most people knew him as Batiste.