chapter 14

Jim Fell and I built a barn on Ginty’s place. It must have been thirty years ago now. We were in her house only once. We stayed in that cabin on the knoll. It isn’t there any more? It seemed a pretty decent cabin when we were there. It had two rooms. One was mostly used for storage and was full of books. When I asked Ginty if I could look at them, she came and locked that part of the cabin up.

She had this pig. She called it “Peggy.” It might have been “Piggy” but Ginty had this strong English accent and it sounded like “Peggy” to me. She doted on this pig. She was going to eat it anyway but she was nuts about it and it ran everywhere. Ginty gave us some preservative to put on the bottoms of the barn posts to stop them rotting. The pig came up and started to lick it. Ginty panicked. “Will it die? Will it die?” she cried. Then she wanted to know if the meat would taste of creosote.

—Joe Cortese

I visited while Jim was working there. We were invited in for tea. I had three kids then, so Kary, who was the eldest, must have been five or six. She was amazed at the goat poop all over the floor. We lived in a tiny rough cabin with no running water and we kept goats, but we never had them in the house. The thing that fascinated my daughter most, however, was on a shelf at her eye level. It was a sealed canning jar full of pickled mice.

—Jeanie Fell

It was actually quite a cold winter. The temperature reached forty below (or close to it) on four different occasions. It was also comparatively sunny. I’ve never minded cold as long as the sun shines. There was very little snow and I didn’t need to have my road ploughed at all. Snowploughs still cruised up and down the highway though, even at night. I could recognize the particular timbre of their motors. There is a point, as they turn a corner at the top of a hill, where their headlights shine through the bay window into the cabin. Try as I might, when I am driving this same stretch of highway, I can see nothing of my dwelling—only bush and the dunes both north and south. I was aghast at first to hear that the ploughs continued to drive up and down when there had been no fresh snow, but it is a safety thing. In this land of no cell phones, scattered habitations and potentially dangerous winter conditions, the road maintenance service patrols every four hours. Between the telegraph road and Nimpo a small cabin stands beside the road. The roof has long gone—it had probably been made of sod—but the walls are still straight and true. It was built by Batiste Dester. It was commissioned as a shelter for road emergencies. This was when it took days to drive to Anahim from Williams Lake. If your vehicle died between Kleena Kleene and Nimpo Lake in the winter, it was an awful long walk to anywhere.

Because there was so little snow I was able to wade through it quite easily and burn most of the brush piles on the building site. I did not want ash pits all over the place so spent a lot of time dragging branches quite a distance. I had some humungous fires. I had fallen several more trees before I left on the book tour, and these were now also limbed and bucked up. It was surprising how many of the bottom branches were solidly frozen to the ground—and how long it took before they could be removed.

One day while working up there, I heard the distant putter of a snowmobile from near the house across the river. Next thing there was a blood-curdling scream. It sounded like a chainsaw about to burn itself out (been there; done that) but much louder. The distance would be at least a kilometre but it cut through my eardrums like a knife. Periodically the sound dropped to a normal snowmobile whine. Then this horrific howl would happen again.

A few days later I was in the cabin enjoying lunch after an invigorating snowshoe trip in gorgeous sunshine. It was a Sunday; soon various snowmobiles fired up across the river and the riders started to zoom round and round the fields. Interspersed with the normal whines was this sudden excessive scream. The machines came to within a hundred metres of the cabin but even when they were at the far end of the property the screaming pierced my brain. The noise, apparently, was deliberate. It came from a racing machine that had been specially tuned. I sat in the cabin with ear protectors on and tears streaming down my face. Was this now to be my destiny? Having these hideous machines destroying every beautiful winter weekend? Later I was talking to the woman of the house on the phone. She didn’t like the noise, either, she said, but her grandson liked to play with it. It was her husband, however, who owned it.

Fortunately, it did not happen as often as I had feared, probably because the snow conditions were so poor; they must have been riding on bare dirt much of the time. Then I learned that these people had been finding homes for their dogs and cats because they were going away. They loved the property but were having a problem finding the money for it. She had found a nursing job in Cape Dorset. They would be leaving shortly and be gone two, maybe three years. They would have no caretakers. Their kids might be up once in a while but the scream machine was to be stored with another neighbour across the road. In the meantime, though, I was to have a respite from it. By the time the couple came back, I would be in my new house. I would still be able to hear it, but it would be that much further away.

It is hard for me to explain to most people why I don’t like living within sight or earshot of neighbours. It is difficult to describe the freedom of spirit that I experience when I cannot see or hear another living soul. I enjoy people when I choose to socialize, but in between I need space. I don’t know why; but without doses of this kind of solitude I cannot be myself.

One day I was trudging along the riverbank, enjoying the delicious emptiness on the other side. The new owners were actually quite pleasant people. She was certainly a conscientious nurse; he was easygoing and friendly. If only they weren’t so noisy with their snowmobiles, barking dogs, and guns. Yes, recreational shooting was another pastime; at one point the grandchildren were actually firing across the river at a silt cliff on my property. At least the owners put a stop to that. My dogs and I walked up there all the time. The youngsters of course thought that all “wilderness” was simply a big playground for them to abuse as they wished.

I tried to imagine what it would be like when Vodka and Lime moved in. They would cut off my access to the river. It would be a while; they had all sorts of other plans they wanted to complete first. By then, perhaps, I would be more inured to the idea of having neighbours. I told myself that it would be good to have a mechanic next door, and someone who would feed my dogs on occasion and help plough the road. Compromise, compromise. Everyone else seems to be able to do it, why not me?

At the beginning of April, Vodka phoned from Vancouver. They were en route back north from Mexico and expected to be home in a week or so. The low snow cover meant that the bush roads were already opening up. I was pleased to see Vodka and Lime planning on an early start in the Chilcotin. They would be in good time to build my house. “Oh we won’t start that right away,” said Vodka. “I have some trucking to do. And the excavator is at Edgar’s. I’ll be doing some work up there with it first. It is too awkward to take it back and forth. We probably won’t start on your place until August.” My heart sank. Did they really think they could begin a house with a full basement in August and have it ready for me to move in before the snow flew? And do all the things they wanted to do with their own place? Was there any real guarantee that the excavator would continue to work? If his truck broke down would he have to attend to that first? They had never built a basement before: Would they be able to do the concrete work properly? I put the phone down and went down to stand beside the river. It was so peaceful having nobody close by. No machinery, no dogs.

And I suddenly thought: Why am I doing this? I would be crazy to trade or sell this place. But what about money? How would I be able to pay for a new house? I would not be able to make enough as a writer; that income paid the bills and that was about it. The mountain business had never made any money at all. It barely paid for itself. I had always run it in a very low-key way as I could not have handled a major tourist business. I don’t have that kind of temperament. It had given me a fabulous place to live and write about but the fibromyalgia and lack of available planes on skis made it difficult to go there in winter. I was now there only in the summer and these months were full of people. I spent all my energies catering to them and had no time to visit many of my favourite places any more, or to enjoy the place alone. Nuk Tessli was no longer the same. I would not be able to keep the mountain business indefinitely, and I was finding it difficult to operate in two different locations. I don’t know why it took so long to come to that conclusion, but it was Nuk Tessli that I would have to sell, not the other title at Ginty Creek.

When I told Vodka and Lime my decision after they arrived home about ten days later, they were livid. “We’ve even spent a lot of money on this fantastic building program for the computer,” they raged, but I no longer knew how much to believe them. Their record was hardly one I could rely on. They now told me they had never liked Gin and I could not blame them for introducing him. We bitched back and forth like that for a while and I agreed to pay them $1,500 for the work they had done trucking stuff to the dump and moving the trailer: they had also taken the steel roof off one of the barns for their extension (without consulting me first) so I figured they were well compensated. Letting people down is not something I am happy doing, but having made that decision I felt as though a great weight had been lifted from my shoulders.

So it looked as though I was going to have to do my own building again. I had no idea when I would be able to complete the house. Putting Nuk Tessli up for sale was one thing. It did not mean that it would be sold in any great hurry. Half the properties on the Chilcotin had For Sale signs at the ends of their driveways; some had been sitting there for years. And Nuk Tessli was not the kind of place most people would be looking for.

There was enough money left from my inheritance to build a basement. I hunted around the property to see if there were any other building materials that I could scrounge. One of the barns was by far the most promising. It was the best made of all the standing buildings and the lumber in it was of good quality. This was the one from which Vodka had removed the steel roofing the previous summer. He was welcome to it: I didn’t want shiny metal on my buildings and would have had to take it off anyway. I found my ladder and a claw hammer half hidden in the long grass beside the barn. They must have borrowed them and left them there. I had not missed the hammer yet but had been wondering where the ladder had got to.

All of Ginty’s barns had feeding areas below and large hay storage spaces above. They had been designed to house goats and the bottom storeys were too low for a human to stand up in. The floor of the barn I wanted to demolish was covered in dried cow poop so presumably Ken had fed his cows in there. The manure would be great for a garden if I ever managed to get one started, but for now it was the upper part of the building that interested me.

It had been built by Jim Fell and Joe Cortese, husbands of Jeanie Fell, the librarian at Tatla Lake, and Deborah Kannegiesser, whom I had also met at the library book club. When speaking to Jim on the phone it was obvious that at least two log buildings that had been on the property thirty years before had disappeared, and the Packrat Palace had not existed then. One warm, slightly hazy spring morning, the four of them came for a visit.

Unlike a lot of the lumber on the place, the material for the barn had come from a sawmill out of the area. Joe had brought a trailer load with him, and this explained its superior quality. Jim remembers that Ginty had just come back from a visit in Fiji. One time she brought to their cabin a brown powder that she made into a tea. It was supposed to produce some kind of effect. It seemed to Jim that Ginty looked at them intently while they drank it but Jim can’t remember feeling anything special. Joe has no recollection of the incident at all.

We trailed over to the Packrat Palace. Few artifacts of interest had been left anywhere on the property, but in a closed-in porch there was an old trunk and a sagging cardboard carton full of much-chewed books and magazines. I had already rescued quite a few volumes—The Thirty-nine Steps, a Maigret, a book of haiku, George Orwell’s Keep the Aspidistra Flying—and I thought I’d found all the good ones, but Deborah started fishing and found all sorts of treasures. First there was a much faded colour photograph of a tall white woman in a white skirt, accompanied by a Fijian woman and several children. A large leaf hid the white woman’s head and there was no indication if it was Ginty or if it was she who had taken the photograph. With it was a curled and stained sepia postcard of an outrigger canoe in full sail. No date, but the canoe was obviously genuine and not something set up for a tourist picture. Then there was a damp-warped hardcover book entitled Life of John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, with portrait, maps and plans. This John Churchill had been born in 1650. The “new edition” of the book had been published in 1904. The book had W.A.B. Paul’s name inscribed in it, and it must have been a prized possession because several lines on every page were underscored with pencil. It looked to be monstrously dull to me—mostly battle tactics as far as I could see. Several mouldy Nature magazines, to which Mr. Paul occasionally contributed, were of more interest but they were published in such an academic way that they were only slightly more attractive. More intriguing was a volume of Working Instructions WIRELESS SET (CANADIAN) No. 19 Mark 111 published by the National Defence (no date), containing strict printed orders that “the information given in this document is not to be communicated either directly, or indirectly, to the Press or to any person not holding an official position in His Majesty’s Service.”

The real gems were a couple of items that Ginty had made. A scrapbook with a red cover bearing a drawing in black ink of a collage of classical architecture boasted the label:

History of Fine Arts

Nedra Jane Paul

January 19, 1954

Book 1

Inside were magazine pictures supplemented by a penned text in Ginty’s large, clear handwriting. The pen used was thick-nibbed, the kind you dipped in ink. A word would fade out, and the following one would start thick and darker until the pen ran out again. Whether she had made this book for herself or her students was unclear. She had selected some very wide-ranging and interesting art pieces. The text was poorly written.

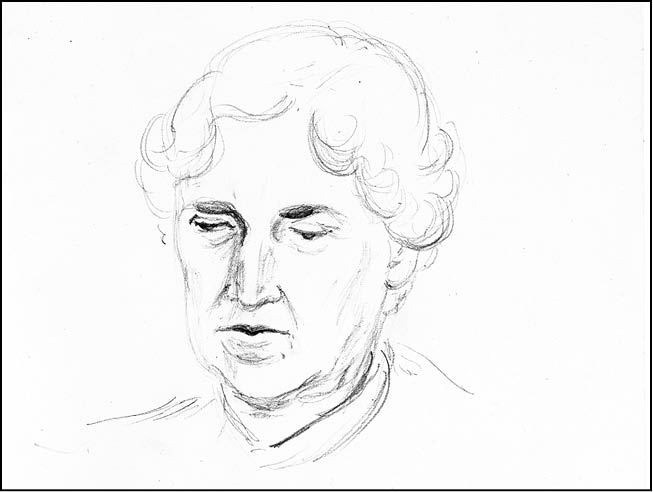

Finally, there was a Public Schools Drawing Book, made in England by Reeves and Sons, Ltd., London. Only a few of the yellowing pages had been used. The drawings had been made with a hard, fine pencil. Two small sketches were of the same man, who had a somewhat nondescript face—he looked too young to have been her father unless she had done the drawings at a much earlier date. There was a stiff and awkward portrait of a young boy sitting on the floor. Four larger drawings were of the face of a woman who could only have been Ginty herself. Self-portraits are always revealing. The face was strong and long, the nose slightly hooked. The eyes were calm.

Self-portrait of Ginty Paul.

When I had pulled the first barn down with Stephanie and Katherine, it had taken maybe half an hour. Jim and Joe’s barn took me five days. The siding had been taken off by wwoofers two years before. Now I ripped the diagonals off the sides and attached the come-along to a tree on a nearby slope. I cranked it so tight I thought the rope might break, but there was not so much as a creak from the barn’s timbers. The rope was very difficult to loosen. I went into the building to cut off more supports. I was scared that the whole thing would come crashing down onto my head, but I climbed out unscathed and when I ratcheted up the come-along again, the barn still wouldn’t budge. Every day I cut more supports. At first I used the chainsaw but in the end I had to perch on top of a ladder that was sitting on a steeply sloping bank. If either the ladder or the building gave way I did not want to be falling with a working chainsaw in my hands, so I hacked away with a handsaw. The remains of the bull were close by and the aroma often wafted over. It was bear season already and sometimes the dogs barked as if something was there. At one point I went to see how the carcass was disintegrating. It had been a slow job because the greater part of the bull had been wedged in the ditch and this had taken a long time to thaw. The ice must have finally loosened its grip, however, because the carcass was now in pieces and pulled up onto a patch of grass. There was little left except the heavy bones and ragged chunks of stiffened, red-haired hide.

Finally the barn came down. I had disconnected the homemade phone extension while I worked as I was worried that the barn might hit it, so that had to be put together again. Now all I had to do was pry apart the useful timber, ferry it over to the building site and start to build my house.