In 1901, the British physician George Still first described a condition he’d observed in children that today is called attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). In a series of lectures he presented to the Royal College of Physicians in England, Still described the causes as being genetic or related to organic brain dysfunction rather than to poor parenting. Still described these children as suffering from what he called an abnormal defect of moral control. As an example, he described a girl who was wantonly mischievous and who threw cups, saucers, and knives at her mother, and screamed and kicked when disciplined (Iversen 2008, 50).

The inattention, excessive fidgeting and poor self-control, which Still initially observed in twenty children, has been called by many different names during the last century. These names are as varied as the many factors proposed as causes. Along with recent insights into the role of genetics and neurobiology in ADHD, today it’s known that ADHD is not exclusive to children and can easily persist into adulthood.

This chapter describes the history of ADHD along with genetic and environmental theories regarding its development; the evolution of its current diagnostic criteria and classifications; the many disorders that can be confused with ADHD; and the association of ADHD and attention deficit disorder (ADD) with other related conditions such as conduct disorders and drug abuse.

One of the most common childhood disorders, ADHD is a psychiatric behavioral disorder. A study evaluating the data of 3042 children ages 8–15 from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed that 8.6 percent of children in the U.S. have ADHD. Boys are diagnosed with ADHD three times more often than girls (Manos 2005). ADHD is characterized by persistent (symptoms lasting at least 6 months) inattention and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity in an individual that is observed more frequently and severely compared to the behavior of other individuals with similar levels of development. Symptoms in ADHD also appear early in life and should occur before age 7. For a diagnosis of ADHD, symptoms must also be present in more than two settings, such as home and school or home and the playground.

Individuals with ADHD have more trouble staying focused and paying attention, and they have difficulty controlling their behavior. Although there are no specific blood or imaging tests used to diagnose ADHD, there are specific diagnostic criteria, which are described later in this chapter. There are also certain genetic and biochemical tests that are used to support a diagnosis of ADHD. Because other medical conditions, such as hyperthyroidism, can cause impulsivity and other symptoms seen in ADHD, it’s important to rule out other metabolic causes before establishing a diagnosis of ADHD.

Hyper-reactivity is characterized by the tendency to be highly emotional and oversensitive. While boys with hyperactivity may become boisterous and show more aggressive and impulsive symptoms, girls with ADHD often have difficulty controlling their emotions in relationships. Girls are also more likely to take offense easily and instigate confrontations by making impulsive remarks. However, according to Dr. Michael Manos, the difference in the sexes isn’t in symptoms. The difference is in the varied expression of behavior in the daily life of men and women, and this is also seen in boys and girls. In general, girls with ADHD have a tendency to lose a sense of internal locus of control (feeling they’re in control of their actions; in external locus of control others are controlling their actions) sooner than boys do. Girls with ADHD also tend to lose their internal locus of control sooner than girls without ADHD (Manos 2005).

As mentioned, ADHD is characterized by inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. Some children may primarily show symptoms related to inattention and others may only show signs of hyperactivity or impulsivity. Symptoms of inattention are seen in individuals who are easily distracted, bored, forgetful and impulsive. Individuals with inattention often have trouble learning new tasks and they frequently have trouble with organization. Daydreaming is common and they may move slowly. Often individuals with inattention do not seem to be fully listening or comprehending what’s being said. Often, children with the inattention of ADHD lose homework or forget to bring assignments home and have difficulty keeping up with classroom work unless the subject is one they have a special interest in.

However, in some ADHD children, distractibility may be concealed by the ability to stick with a particular activity for extended periods. Typically, this happens when they’re involved in an activity of their choice, for instance computer games, in which they seem to play obsessively (Wender 2000, 12). However, not all experts agree with Dr. Wender’s views (Carson 2010, xv).

Individuals with ADHD who have symptoms of hyperactivity often fidget or squirm in their seats. They often talk nonstop and dash around, touching or playing with everything they encounter. Seemingly in perpetual motion, the have trouble sitting still during school and during meals, and they have difficulty participating in quiet tasks or activities.

Individuals with impulsivity symptoms in ADHD are often impatient, tend to blurt out inappropriate comments without restraint or forethought and act without regard to the consequences. They display impatience if having to wait in line or wait their turn in games, and they frequently interrupt conversations or others’ activities. Some children with ADHD have problems with bladder and bowel control. When younger, some ADHD children may wet or soil themselves during the day and not pay attention to their body’s needs. Bed-wetting, which occurs in about 10 percent of all 6-year-old boys, is seen more frequently in ADHD children (Wender 2000, 15). Other experts, such as Dr. Benjamin Carson, a professor of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins Medical School, writes that the ability to play video games without being distracted indicates that one does not have ADHD (Carson 2010, xv).

Heightened impulsivity is a risk factor for drug abuse. Individuals with high impulsivity may be more likely to experiment with drugs, more likely to continue using drug’s after initial exposure, and have more difficulty abstaining once they’ve used drugs on a regular basis (deWit and Richards 2001). Studies in ADHD show that children with impulsivity show more rapid discounting of the value of delayed consequences. The serotonin system is thought to be critically involved in the ability to inhibit or stop impulsive responses, whereas the dopamine system is involved in the valuation of delayed consequences. The direct experience of rewards and delays also affects impulsivity and is considered in behavioral therapies for ADHD.

The three subtypes of ADHD in use today include:

• Predominantly hyperactive-impulsive (HI)—in this subtype most symptoms (usually six or more) are in the hyperactivity-impulsivity categories; fewer than six symptoms of inattention are present, although inattention may be present to some degree.

• Predominantly inattentive (IN)—in this subtype the majority of symptoms (usually six or more) are in the inattention category and fewer than six symptoms are of the hyperactivity-impulsivity type, although hyperactivity-impulsivity may be present to some degree. Children with this subtype are less likely to act out or have difficulty getting along with other children. They may sit quietly but are usually not paying attention to what they’re doing or their surroundings.

• Combined hyperactive-impulsive and inattentive (CB)—in this subtype, which is the most common subtype seen in children, individuals have six or more symptoms of inattention and six or more symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder [ADHD] 2008, NIMH).

Individuals who predominantly have inattention and combined types are more likely to have academic deficits and school-related problems. Individuals with predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type tend to have more problems with peer rejection, social interactions and accidental injuries. Females are represented more in the predominantly inattentive type.

The pathology or causes of disease development in ADHD are unclear. The effective use of psychostimulant medications and noradrenergic tricyclic antidepressants in ADHD suggests that certain brain areas related to attention are deficient in neural transmission, particularly in regards to dopamine and norepinephrine in the frontal and prefrontal regions of the brain. The parietal lobe and cerebellum may also be involved, and right prefrontal neurochemical changes in adolescents with ADHD have also been found.

ADHD has been described as a disorder of the active inhibition of impulsive behavior. According to this hypothesis, the relative inability of ADHD patients to perform well in academic and social situations is a consequence of increased stimulus-control of behavior and reduced capacity for self-regulation at the cognitive level. Several researchers have suggested that dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex is fundamental to ADHD, considering the resemblance between patients with ADHD and patients with brain damage restricted to the frontal lobe (Taylor and Jentsch 2001, 121–2).

Stimulant drugs increase movement and motivation. These processes depend upon increases in dopamine transmission within the brain’s limbic system. Neurochemical actions within the frontal cortex may also contribute to the ability to modulate some of these basic motivational processes (Taylor and Jentsch 2001, 123). PET scan imaging studies indicate that methylphenidate and amphetamines act to increase dopamine (Soreff 2010). Stimulants also cause increased norepinephrine levels. However, the effect of norepinephrine on alterations in cognitive function in ADHD is unknown, although benefits of norepinephrine are presumed to be related to its arousal-enhancing actions (Berridge, 2001, 177).

In a paper presented at the 63rd Annual Scientific Meeting of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the psychiatrist R.D. Rogers showed how reduced central serotonin deficiency induced by tryptophan depletion causes symptoms of impulsivity. This study suggests that serotonin modulates the functions of the orbital prefrontal cortex, including modulation of the choices made between reward and resultant changes in mood in vulnerable individuals (Rogers 2001).

Dopamine pathways (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, NIDA).

Reports estimate that the prevalence of ADHD worldwide is 5.3 percent. In the United States, approximately 8.6 percent of children 4 to 17 years old have been diagnosed with ADHD at some point in their lives, and in 2010 the incidence in school-age children was reported to be 3–7 percent (Soreff 2010; Merikangas et al., 2010). In addition, about 4.4 percent of adults in the United States from ages 18 to 44 years are also affected (www.shire.com). Overall, about 4.4 million children and almost 10 million adults are estimated to have ADHD. Several studies show that ADHD runs in families. Parents with symptoms of ADHD have a 1 in 4 risk of having children with ADHD (Iversen 2008, 54). In adults with ADHD, males and females are equally affected, although in children more boys are affected than girls. While an increasing number of children have been diagnosed with ADHD in recent years, this is attributed to greater awareness of ADHD among medical professionals, knowledge that it may persist into adulthood, and the recognition of multiple subtypes. Differences in the incidence of ADHD in different states suggest that there may be differences in how ADHD is diagnosed in different parts of the country. Before the name ADHD came into use, disorders now termed ADHD went by a number of different names, including minimal brain dysfunction.

Minimal Brain Dysfunction

In the 1960s, Paul Wender, director of the Division of Psychiatric Research at the University of Utah, first coined the term “minimal brain dysfunction” to describe the behavioral condition first reported in children that’s now known as ADHD (Wender 1975). Wender chose this term to contrast it from psychiatric disorders related to brain injuries. Although early studies showed minimal brain dysfunction to be the most common psychiatric disorder in children, by 1972 Wender had proposed that this disorder had genetic origins and that it often persisted for life. For more than 35 years Dr. Wender has treated patients with ADHD and conducted research on this condition. He also developed the Wender-Utah scale (WUS) to help with the diagnosis of ADHD.

The second edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) published in 1968 referred to the condition now called ADHD as “hyperkinetic disorder of childhood.” The DSM is a publication of the American Psychiatric Association that describes and defines psychiatric disorders. DSM criteria are one of the major references used to help diagnose psychiatric disorders. In 2010, the DSM criteria in current use are those published as DSM-IV-TR, with TR indicating that there were later text revisions made to the original DSM-IV guidelines.

The criteria for hyperkinetic disorder listed in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) published by the World Health Organization (WHO), which is primarily used in Europe, is similar to the criteria listed in the 1994 DSM-IV guidelines for ADHD, although the ICD-10 guidelines refer to this condition as “hyperkinesis.” In both classifications, symptoms for both inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity are required for a diagnosis of ADHD or hyperkinesis and the child must have an IQ higher than 50.

Although other guidelines and criteria are sometimes used, the DSM and ICD-10 guidelines are the primary resources used by physicians, researchers, policy makers, insurance companies, and drug regulatory agencies.

The ICD-10 guidelines established in 1990 do not recognize subtypes of hyperkinesis. Children with subsets of symptoms are considered “subthreshold” cases. Also, the ICD-10 guidelines are more strict compared to the DSM guidelines regarding direct observation. Rather than using the parents’ or teachers’ words to establish diagnosis, symptoms must be directly observed by the clinician. Onset of symptoms must also have started by the age of 6 years.

In conditions of hyperkinesis, inattention is defined by an individual’s premature termination of tasks and the tendency to leave activities, schoolwork, and chores unfinished. Children with hyperkinesis bounce from one activity to another, seemingly losing interest in a particular task because of their limited attention span and tendency toward distraction. Overactivity, defined by these guidelines, is manifested by excessive restlessness, especially in situations requiring relative calm. For example, a child with hyperkinesis may be observed running and jumping around, not sitting still when required to do so, talking excessively and noisily or fidgeting. Hyperkinesis is diagnosed when the activity of the individual is excessive in the context of expected behavior and self-control, and by comparison with other children of the same age and IQ in structured, organized situations that require a high degree of behavioral self-control.

The following features aren’t necessary for the diagnosis of hyperkinesis, but their presence in individuals who have been previously diagnosed implies that a diagnosis of hyperkinesis still exists: disinhibition in social relationships, recklessness in situations involving some degree of danger, and impulsive flouting of social rules.

The third edition of the DSM published in 1980 referred to the condition now called ADHD as “attention deficit disorder (ADD).” This change in nomenclature reflected a significant shift toward recognizing the inattention that characterizes this disorder. Previously, the focus had been on motor activity and the inattention was considered a secondary feature. With the term ADD, the primary inattentiveness in ADHD, influenced by the work of the child psychiatrist Virginia Douglas, was recognized. The DSM-III classification also recognized for the first time that there were two major subtypes of ADD, one with and one without hyperactivity. In both subtypes, impulsivity was considered a necessary symptom for diagnosis.

However, in the revised DSM-III-R classification published in 1987 the subtypes were no longer recognized because of insufficient reporting evidence. The symptom of hyperactivity was restored to its status as a core symptom, along with inattention and impulsivity, for a diagnosis of the disorder now called attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

In the revised DSM-III-R diagnostic criteria published in 1987 behavioral criteria for a diagnosis of the disorder now referred to as ADHD included 14 symptoms spanning the core manifestations of hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity. For a diagnosis of ADHD, 8 symptoms needed to be present. Because the list of symptoms included fewer than 8 symptoms pertinent to inattention, children with inattention alone were relatively unlikely to be diagnosed (Solanto 2001, 4).

After these guidelines were published, research studies using factor analysis were presented that showed clearly that children with ADHD overwhelmingly had behavioral symptoms involving both hyperactivity and impulsivity. In field studies used to establish the DSM-IV guidelines, researchers verified that these clusters of symptoms can occur separately or together in individual children. Therefore, when the DSM-IV guidelines were introduced in 1994, three subtypes of ADHD were recognized, as described earlier in this chapter.

There is no single test available to diagnose ADHD. The diagnosis is based on observations by parents and teachers of past and current behavior. The behavior in ADHD must include a minimum of required symptoms listed in the various guidelines, such as those described in the ICD-10 or DSM-IV or in the numerous rating scales used to evaluate symptoms. In additions symptoms must have first occurred early in life and persisted for at least 6 months in more than one area (school, home, playground, social situations, etc). Before diagnosing ADHD, other conditions that could cause similar symptoms—such as depression, anxiety, learning disorders, and post-traumatic stress syndrome—must be ruled out. In some instances, children are also tested for food and environmental allergies, nutrient deficiencies, hearing and vision disorders and metabolic disturbances.

Symptoms may also be assessed by standardized psychological evaluations such as the comprehensive Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children and Adolescents (DISC), the Wender Utah Rating Scale (primarily used in adults), the Barkley Home Situations Questionnaire, or the Connners Parent and Teacher Rating Scales.

Tests by the National Institutes of Mental Health using monitoring devices show that activity is increased in children with ADHD during routine activities and also during sleep. Impulsivity has been evaluated using the continuous performance test (CPT) and the Test of Variable Attention (TOVA). Children with ADHD are shown to perform more errors of commission. However, CPT results haven’t been shown to correlate well with observations made by teachers. Attention deficits have been the most difficult for researchers to evaluate using clinical tests, although children with ADHD have been shown to have longer reaction times.

The American Psychiatric Association has prepared a set of guidelines that describe the characteristics of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity seen in ADHD. These guidelines help distinguish individuals who have predominant symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity from children who primarily have inattention or who have a combined type of ADHD with characteristics of both of the other subtypes (American Psychiatric Association 2000).

While there is no one imaging test that can diagnose ADHD, neuroimaging studies have been helpful in explaining the pathology seen in ADHD. Changes in brain anatomy were suspected early on in ADHD because of reports of changes in similar disorders. For instance, changes in neurotransmitter circuits, particularly in the cortico-striatal-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) circuits have been seen in obsessive-compulsive disorders, in most movement disorders, and in Tourette’s syndrome (Castellanos 2001). With the introduction of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques in the late 1980s and positron-emission tomography (PET) scans, researchers were given the means to explore the changes in ADHD.

Neuroimaging studies have contributed to the characterization of the ADHD phenotype. Anatomic MRI has shown smaller volume in the right prefrontal brain regions, caudate nucleus, globus pallidus and a subregulation of the cerebellar vermis. These volumes (with the exception of the cerebellum) were negatively correlated with inhibitory control in children with ADHD. However, MRI and PET studies haven’t always shown consistent findings. One study found greater frontal activation on an easy response-inhibition task, and lesser striatal activation in children forming a harder variation of the task. In conclusion, imaging studies suggest that ADHD reflects dysfunction and dysregulation of cerebellar-striatal/adrenergic-prefrontal circuitry. Psychostimulants are effective in modulating and regulating this circuitry (Castellanos 2001).

At his clinic in California, Daniel Amen, M.D., has used imaging studies of the brain to help diagnose and treat both children and adults with ADHD since 1991. Using single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging, Dr. Amen reports that he is able to differentiate classic attention deficit disorders from disorders primarily of inattention, primarily causing overfocus, primarily affecting the temporal lobe, primarily affecting the limbic system, or primarily causing moodiness or anger (“Ring of Fire” disorders). After determining the basic disorder from the patient’s imaging scans, Dr. Amen prescribes treatment individualized for the patient (http://www.amenclinics.com/clinics/information/ways-we-can-help/adhd-add/ accessed March 15, 2010). This procedure involves injecting the patient with a small amount of a radioactive tracer.

However, according to Russell Poldrack, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles, although brain images can provide solid evidence of alterations in brain structures and functions associated with psychiatric disorders, they cannot yet be used to diagnose psychiatric disorders or determine how treatment works. Poldrack writes that functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has revolutionized safe brain imaging techniques and allowed researchers worldwide to learn about the brain’s function. However, evidence from research shows that imaging is limited because the conclusions are based on groups of people with a specific disorder and not individual results. In addition, brain activity has many different causes and it’s impossible to pinpoint specific causes. Brain imaging is important because it can provide evidence of a biological basis for psychiatric disorders. It can also provide the means to reach beyond diagnostic categories to better understand how brain activity relates to psychological dysfunction.

Poldrack writes that Amen’s own research with SPECT imaging reports accuracy of less than 80 percent in predicting treatment outcomes. Poldrack feels that even this number could be exaggerated because the Ring of Fire study, for example, involved 157 children overall and excluded 120 patients who did not show activation in a particular brain region. Based on this evidence, Poldrack writes, “It seems unlikely that the potential benefits on treatment outcomes justifies exposing children to even the small amounts of radiation from SPECT scans” (Poldrack 2010).

In a 2005 report, the American Psychiatric Association affirmed this opinion in saying that the available evidence does not support the use of brain imaging for clinical diagnosis or the treatment of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents (The American Psychiatric Association 2005).

Ever since attention disorders were first described as a medical condition in children, there’s been concern that normal children were being diagnosed with psychiatric disorders. The huge increase in the number of children diagnosed with ADHD from 1970 to 2003 has interested more scientists in finding definitive causes. In 1970, 150,000 American children were diagnosed with ADHD. In 2003, this number rose to 4.5 million (Hershey 2010).

While no specific cause has been identified, a number of environmental and medical causes of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity exist. Food allergens, food additives, endocrine disorders, toxic chemicals, brain injuries, nutrient deficiencies and metabolic disorders have all been found to cause symptoms that might easily be mistaken for ADHD. It’s also suspected that some of these causes, particularly food additives and pesticides, are contributing to the biochemical changes seen in ADHD. Some of the other suspected causes of ADHD are described later in this chapter.

Several physicians, such as the child and adult neurologist Dr. Fred Baughmann, also believe that children who are more spirited or high-strung are being mistakenly diagnosed with ADHD, a disorder he feels was created by the pharmaceutical industry (http://www.adhdfraud.org). In 2000, Peter Breggin, M.D., testified before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations Committee on Education and the Workforce and criticized what he described as an excessive use of psychostimulants for ADHD (Breggin 2000). While questions regarding diagnostic criteria have arisen and are described in Chapter Nine, most experts worldwide are in agreement that ADHD is a psychiatric condition that responds well to psychostimulant medication. Studies showing a link to environmental agents and ADHD help to explain the increasing number of children affected by ADHD.

While the emphasis given to certain symptoms in ADHD, such as hyperactivity, has changed from time to time, the core description of ADHD has remained essentially the same regardless of the guidelines used. However, the causes of ADHD have remained elusive. The discovery that stimulants helped reduce symptoms in ADHD led to additional neuropsychiatric studies showing various genetic-induced biochemical changes as a definitive cause. In addition, several studies have also shown that stimulants improve behavior and attention in individuals, including children, with no signs of ADHD or any other mental disorder. As described in Chapter One, most people feel better and work more efficiently under the influence of low-dose stimulants.

Although researchers haven’t yet found one gene responsible for ADHD or one environmental trigger responsible for its development, certain genetic and environmental factors have been found to contribute to the development of ADHD. The possibility that the most common subtype of ADHD, the CB subtype, has different causes than the other subtypes also exists. The following section describes the causes of ADHD based on studies primarily involving the CB subtype of this disorder.

Humans are reported to carry at least 250 chemical contaminants in their bodies (Colborn et al., 1997). Recent studies suggest the number of chemical contaminants is closer to one thousand (Junger 2009). Some of the most pervasive of these environmental chemicals include the polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), DDT, and dioxin. Since the Toxic Substances Control Act became law in 1976, the number of chemicals in commercial products has risen from 60,000 to 80,000, yet the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has required testing on only 200 chemicals and restricted just five (DiNardo and Webber 2010). Of the chemicals tested, the EPA allowed the chemical manufacturers to run their own tests in many cases (Fagin and Lavelle 1999, 35–6). Although production of some of the most hazardous chemicals has declined in recent years, these chemicals are part of our chemical legacy, one that we pass on to our children. In their book Our Stolen Future, Theo Colborn and her colleagues report that long before concentrations of synthetic chemicals reach sufficient levels to cause obvious physical illness or abnormalities, they can impair learning ability and cause dramatic, permanent changes in behavior, such as hyperactivity (Colbon et al., 1997, 186). Both animal experiments and human studies report behavioral disorders and learning disabilities similar to those that parallel the current rise in ADHD.

Scientists don’t have a complete understanding of how PCBs impair neurological development in the womb and early in life, but emerging evidence suggests that the ability of PCBs to cause brain damage stems in part from disruption to another component of the endocrine system, thyroid hormones. Thyroid hormones are essential for normal brain development. Thyroid hormones stimulate the proliferation of neurons and later guide the orderly migration of neurons to appropriate areas of the brain. PCBs, dioxin and other chemicals disrupt the endocrine system by reacting with cell receptors intended only for thyroid hormone. As endocrine disruptors, the chemical toxins prevent thyroid and other hormones from activating cell receptors and assisting in normal fetal development.

The emerging evidence linking PCBs to thyroid disruption and neurological damage is especially worrisome because PCBs have held steady in recent years, despite initial drops in the 1970s related to bans in the United States. In the former Soviet Union, production of PCBs continued through 1990. Based on the concentrations in breast milk fat of PCBs, there are estimates that at least 5 percent of babies in the United States are exposed to sufficient levels of contaminants to cause neurological impairment. Laboratory animals exposed to PCBs in the womb and early in life show behavioral abnormalities as adults, including pacing, spinning, depressed reflexes, hyperactivity and learning deficits (Colborn 188–9). Thyroid hormone resistance, a disorder described later in this chapter, is considered a result of thyroid hormone receptors damaged by endocrine-disrupting chemicals. These endocrine-disrupting chemicals include, lead, PCBs, polybrominated biphenyls, dioxins, and hexachlorbenzene (Krimsky 2000, 45–7).

The organochlorine pesticides are environmentally persistent contaminants. Originally developed for warfare, organochlorines destroy the nervous system of insects. The evidence for organochlorine compounds causing neurodevelopmental effects in children continues to grow while studies on behavioral outcomes are now starting to emerge. In March 2010, Harvard researchers reported that prenatal exposure to organochlorine is associated with ADHD in school children (Sagiv et al., 2010). In a related study from the Harvard School of Public Health, researchers found that higher levels of organochlorines are seen in the urine of children with ADHD. While more studies are needed, scientists are recommending buying organic fruits and vegetables and rinsing fruit well before eating.

This theory of ADHD being related to organochlorine chemicals is supported by instances of rice oil contaminated with PCBs and other organochlorine compounds in Japan in 1968 and in Taiwan in 1978–79. People who consumed these oils became sick. Their offspring have been followed and been found to have small size and weight, hyper-pigmentation, nail deformities, cognitive disturbances, and behavioral problems. The detoxification systems of children are immature and this causes children to have significantly higher effects from environmental toxins. Studies at Wayne State University also discovered adverse cognitive effects of PCBs in children who otherwise appeared healthy (Krimsky 2000, 48).

Many investigators have attempted to describe ADHD in terms of fundamental behavioral or psychological characteristics. The most influential theory is one that suggests that a core deficit in inhibitory control impairs the normal development of executive functions that are necessary for internal self-regulatory mechanisms involving behavior, cognition, and emotions using the executive abilities of working memory, affect-motivation-arousal, speech internalization, and behavioral analysis (Barkley 1997). This theory, while promising, has not been confirmed.

Numerous studies have confirmed a significantly increased relative risk of ADHD occurring in siblings, children and parents of individuals with ADHD. Risk for ADHD has also been found to be higher in biological parents than adoptive parents. Identical twins also have more than double the concordance rate of ADHD compared to fraternal twins. In addition, studies show that a shared environment is not a significant factor. ADHD has also been shown to occur more often in families with major depressive disorders and bipolar disorders.

Children with ADHD who carry a particular version of a certain gene have been found to have thinner brain tissue in the area of the brain that’s associated with attention. This research, which was conducted by the NIMH, showed that the difference was not a permanent change. As children with this gene grow and mature, their brains develop to a normal level of thickness and their ADHD symptoms improve (Shaw et al., 2007).

Like other psychiatric disorders, ADHD is not likely to be caused by a single gene. Studies also suggest that the genes that contribute to inattentiveness are different from the genes responsible for hyperactivity-impulsivity.

Several different candidate genes that control dopamine have been proposed as contributing to ADHD because of the overwhelming consensus that dysregulation in dopamine production is the core underlying defect. Vulnerability to ADHD may be caused by many contributing genes. The following genes have been associated with this disorder: DRD4, DRD5, DAT, DBH, 5-HTT, and 5-HTR1B. ADHD risk has been shown to be significantly increased in the presence of one risk al-lele in genes DRD2, 5-HTT and DAT1.

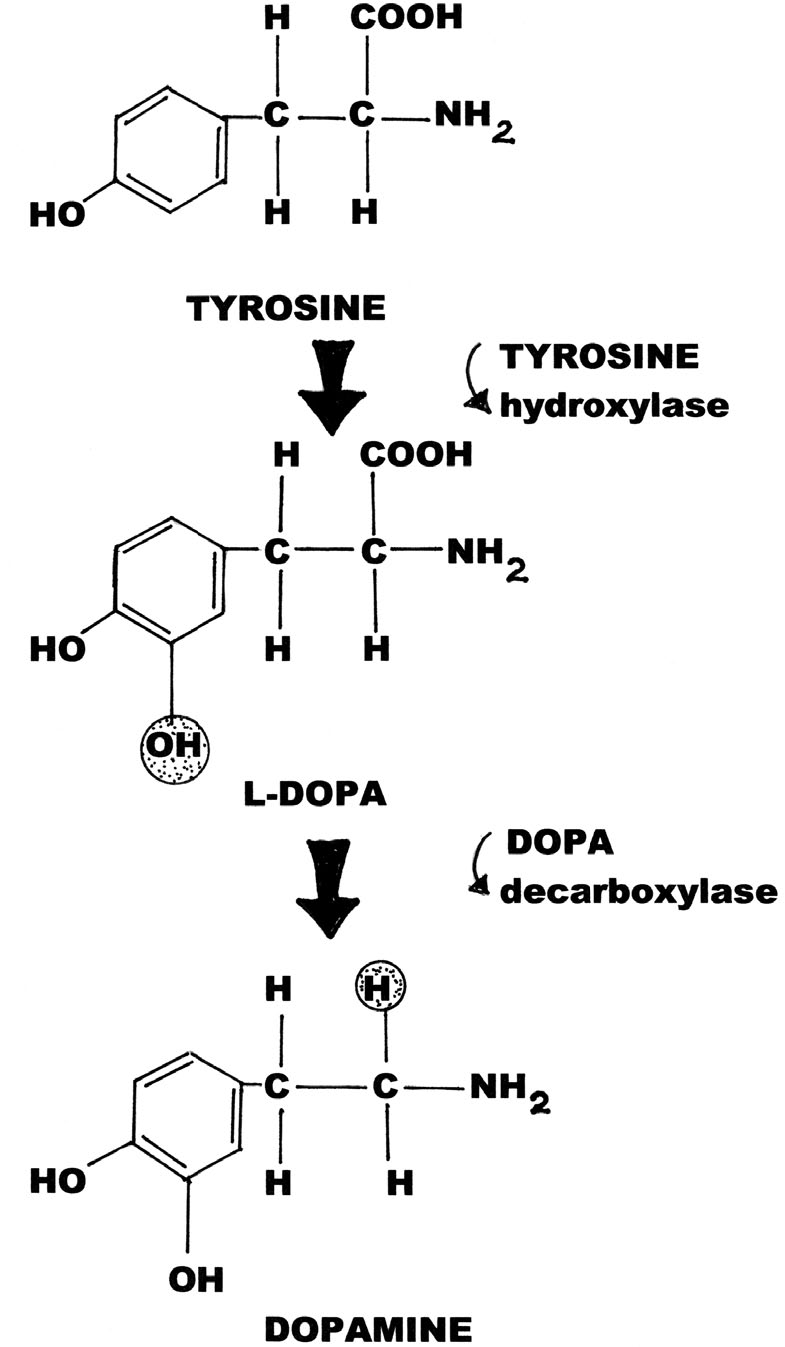

Production of dopamine from tyrosine (courtesy Marvin G. Miller).

Although most studies show low dopamine levels to be associated with ADHD, several studies show that higher levels of a dopamine metabolite, homovanillic acid (HVA), are associated with more severe forms of hyperactivity. This suggests that any imbalances or abnormalities in dopamine contribute to ADHD. Polymorphisms on the dopamine transporter (DAT) gene and variants of the dopamine 4 receptor are currently under investigation. The DRD4 variant associated with the psychological train of novelty seeking has been significantly associated with ADHD. These two gene candidates are thought to modestly contribute to ADHD, along with influences from genes that regulate norepinephrine.

A lower socioeconomic status has been linked to ADHD and it is seen in both biological and adoptive families. In adoptive families, ADHD is more likely to be seen in families with a lower socioeconomic standing. Several theories have proposed suggesting that ADHD is influence by in utero exposures to toxic substances, food additives or colorings or allergens. Children are at increased risk for ADHD if their mothers were exposed to toxins, smoked, drank or used alcohol during pregnancy. Children who were born prematurely or who were exposed to environmental toxins as children are also at increased risk.

Personality in combination with genetics is also thought to play a role. Personality traits that have been described in ADHD include high neuroticism, stubbornness and low conscientiousness. Of greater significance, several infectious agents have been proposed as causes. The first widespread description of an ADHD-like disorder followed the pandemic of encephalitis lethargica (von Economo’s encephalitis) that occurred during the late 1910s and early 1920s (Wender 1995, 79). Behavioral changes in children such as irritability and emotional instability occurred as after-effects of encephalitis in children. French researchers described these changes as deviations of moral character and included lying, temper tantrums, distractibility, violence and symptoms of conduct disorder. Von Economo, a physician, described the changes he observed in children following recovery from encephalitis as those of maniacal excitation. Researchers also found changes in gray matter and some researchers theorized that there was an organic basis for the behavioral changes.

Studies in the past few years have shown that boys with ADHD tend to have brains that are more symmetrical in shape. Three structures in the ADHD boys’ brains were smaller than in non–ADHD boys of the same age: prefrontal cortex, caudate nucleus, and the globus pallidus. The prefrontal cortex is thought to be the brain’s “command center”; the other two parts translate the commands into action. In addition, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have shown that some regions of the frontal lobes (anterior superior and inferior) and basal ganglia (caudate nucleus and globus pallidus) are about 10 percent smaller in ADHD groups than in control groups of children, and molecular genetic studies have shown that diagnosis of ADHD is associated with polymorphisms in some dopamine genes (the dopamine D4 receptor gene and the dopamine transporter gene) (http://faculty.washington.edu/chudler/adhd.html accessed March 1, 2010).

Numerous metabolic, sensory and endocrine disorders can cause symptoms similar to those of ADHD, including classic symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity and inattention. It’s important to rule out other causes before starting treatment for ADHD. At the minimum, a laboratory panel including a CBC, thyroid function tests, adrenal function tests, a comprehensive metabolic profile, a hemoglobin A1C, and a urinalysis should be ordered to rule out other causes along with sensory integration dysfunction testing, and with tests for hearing and vision.

Various endocrine disorders, including diabetes, thyroid and adrenal disorders can cause symptoms similar to those caused by ADHD. In children with diabetes, a low blood sugar can cause poor concentration, inattention and fatigue, whereas a high blood sugar can cause hyperactivity and jitteriness. Early-onset diabetes can cause symptoms of depression, aggression and anxiety.

Physicians at the University of Maryland School of Medicine have found a positive correlation between elevated levels of certain thyroid hormones and hyperactivity/impulsivity. In their study Peter Hauser and Bruce Weintraub studied 75 individuals diagnosed with resistance to thyroid hormone and 77 of their unaffected family members. They measured levels of the thyroid hormones T3 and T4 and also TSH, a pituitary hormone that regulates thyroid function, and evaluated symptoms of both inattention and hyperactivity. The researchers found that high concentrations of T3 and T4 were significantly and positively correlated with hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms but not with symptoms of inattention. They concluded that elevated thyroid hormone levels provide a physiologic basis for the dichotomy between symptoms of inattention and symptoms of hyperactivity that are sometimes seen (Donovan 1997).

Sensory integration dysfunction refers to the inefficient neurological processing of information received through the senses. This condition causes problems with learning, development and behavior. Affected children are over-sensitive or under-sensitive in regards to taste, touch, smell, sight or sound. Children with sensorineural disorders tend to crave fast and spinning movements and can often be seen swinging, rocking, and twirling without any signs of dizziness. Symptoms also include constant movement, constant fidgeting and risky behavior. Affected children may show signs of overexcitement and be inattentive in the classroom setting. These children also often act out due to inability to process sensory information. At the NeuroSensory Center in Austin, Texas, Dr. Kendall Stewart tests neurotransmitter levels and treats ADHD with peptides and nutrients (http://www.drkendalstewart.com/treatment_autism.html).

Impaired hearing or vision can also cause symptoms of ADHD. Children unable to see the blackboard clearly or who have dyslexia can show inattention and fidgeting.

Central Auditory Processing Disorder may sometimes occur in children who have a history of ear infections. Symptoms include distractibility, inability to follow instructions, and inattention.

Symptoms in ADHD and borderline personality disorder are very similar. In the Utah Criteria, researchers clearly distinguish the two disorders and exclude people with characteristic and unique traits of borderline personality disorder. The borderline attributes include impulsivity, angry outbursts, affective instability, and feelings of boredom. However, these attributes are of a different quality and intensity as those seen in ADHD. Impulsivity in ADHD is short-lived and situational, for instance running a traffic light or talking before thinking. In borderline personality behavior, impulsivity is more driven and compulsive and includes shoplifting and bingeing. Anger is also constant compared to the occasional outbursts seen in ADHD and certain features such as suicidal ideation, unstable, intense interpersonal relationships, and self-mutilation are more likely to be seen in borderline personality disorder (Wender 1995, 131).

Mild to high lead levels can cause attention deficits, hyperactivity and poor school performance. Elevated carbon monoxide levels from exposure to cigarette smoke and defective gas appliances can cause inattention and drowsiness. High mercury levels and high manganese levels can also cause symptoms of hyperactivity. Toxic doses of vitamins and the build-up of medications used for allergies can cause hyperactivity.

A study of 4,000 children in England has found that children eating a large amount of junk food and food additives are more likely to exhibit hyperactive behavior. Nicola Wiles and her colleagues at the University of Bristol assessed the dietary habits of children at age 4½ years. The mothers of the children completed a questionnaire relating their children’s consumption of 57 foods and beverages including ice cream, milk chocolate bars, pizza, pasta, soft drinks, and vegetables. The children were evaluated again at age 7 and their mothers completed the Strengths and Difficulties test. Children who consumed the most junk foods were more likely to be in the top 33 percent of scores indicating hyperactivity. Wiles recommends that a properly supervised trial eliminating colors and preservatives from the diet of hyperactive children should be considered a part of standard treatment (Wiles 2009). Previous research in 2007 showed that normal children without any symptoms of ADHD became significantly more hyperactive after eating a mixture of food colorings and the preservative sodium benzoate (McCann et al., 2007).

The link between artificial food additives and hyperactivity was first discovered by the late San Francisco allergist Ben Feingold. The Feingold diet was one of the first nutritional interventions used in ADHD. The link in additives is also suspect because consumption of food dyes has increased almost threefold since the 1980s, rising from about 6.4 million pounds in 1985 to more than 17.8 million pounds in 2005 (Hershey 2010). In the U.K., food manufacturers are removing most synthetic dyes from food products. In the United States, the American Academy of Pediatrics acknowledged that a trial of preservative-free, food coloring-free diet is a reasonable intervention for hyperactive children, and nineteen prominent scientists signed a letter urging Congress to ban these additives (Hershey 2010).

Children with gluten sensitivity may show symptoms of hyperactivity and inattention after eating foods with gluten. The Centers for Disease Prevention and Control reports that one in every 133 Americans has gluten sensitivity and only about 3 percent of individuals with this disorder are properly diagnosed. Children with milk allergies can also show symptoms of hyperactivity. It’s thought that the gluten and casein proteins in these disorders are not properly digested and form morphine-like compounds that lead to behavior problems.

Children who ingest foods and drinks with high levels of caffeine, including soda pops, can have symptoms of hyperactivity related to excess caffeine. Caffeine is also found in a number of medications, including analgesics and allergy medications. Some children are particularly sensitive to caffeine and react to even small amounts.

Although studies show that only a small percentage of children with symptoms of ADHD have suffered a traumatic brain injury (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, NIMH 2008), it’s important that a doctor check for possible injuries before a diagnosis is made. Brain cysts, post-concussion injuries and early stage brain tumors can all cause symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity. Post-concussion syndrome can damage brain cell pathways, leaving the individual poorly able to utilize higher brain cognitive and executive level thought processing abilities, leading to sensory input disorders. Positive emissions tomography (PET) scans can identify damage.

Both fetal alcohol syndrom (FAS) and fetal alcohol effects (FAE) are caused by mothers who drink heavily during pregnancy. While FAS can cause physical changes and overt mental retardation, it can also cause milder symptoms include those of hyperactivity. FAE is less likely to be diagnosed because physical changes aren’t apparent. However, FAE is highly associated with attention problems, learning disorders, hyperactivity, and conduct disorders.

Generalized anxiety can cause symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity. Mild forms of depression can cause irritability, attitude problems and inattention. Other symptoms may include sleepiness, insomnia, appetite changes, crying, lack of energy and poor self-esteem (http://www.drhuggiebear.com/information/whenitsnotadhd.htm accessed March 10, 2010).

A disorder known as the absence seizure, can cause children to stare excessively or jerk repetitively. Children with persistent absence seizures can have symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity. Some medications used for seizure disorders can cause drowsiness and inattention.

Experts report that 85 percent of children with child-like bipolar disorder have symptoms that meet the diagnostic criteria for ADHD. Unlike the symptoms seen in adults, children with the early onset disorder can have rapid cycling of mood swings. They move quickly from being calm to having full-fledged tantrums. Symptoms include distractibility, hyperactivity, impulsivity, separation anxiety, restlessness, depression and low self-esteem.

Parasitic, viral, and bacterial infections can all cause symptoms of distractibility, inattention, and hyperactivity.

Some mild genetic disorders can go undiagnosed in children and cause symptoms similar to those of ADHD. Mild forms of Turner’s syndrome, sickle-cell anemia and Fragile X syndrome can cause hyperactivity.

Tourette’s syndrome can cause children to be appear disruptive and hyperactive. The tics associated with Tourette’s and with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcus (PANDA) are often confused as symptoms of hyperactivity. PANDA syndrome is also associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and symptoms can be confused with those of inattention or impulsivity.

With a proper diagnosis and treatment, children with ADHD can do exceedingly well in school. Studies show that psychostimulant medical treatment is more effective than psychosocial programs for the treatment of ADHD. Without treatment, children with ADHD are more likely to have difficulties with school and other authorities and are more likely to have problems with drug abuse. In some cases drugs such as cocaine are used as a form of self-medication for ADHD. At the Florida Detoxification Center, about 70 percent of the drug addicts they treat are found to have undiagnosed and untreated ADHD (http://www.floridadetox.com/).

Children and adults with ADHD may have coexisting conduct disorders. In some cases individuals with conduct disorders are misdiagnosed as having ADHD. It’s estimated that about 20 to 30 percent of children with ADD have learning disorders. Based on studies in clinics—which may be higher than rates seen in ADHD in the general population—about 35 percent of ADHD children have oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and more than 25 percent have conduct disorder (CD) (Wender 2000, 11).

Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) is described as a recurrent pattern of negativistic, defiant, disobedient, and hostile behavior toward authority figures. Children with ODD often have trouble controlling their tempers and they tend to argue with adults, actively defy requests from authority figures, deliberately do things that annoy others and tend to be angry, resentful, spiteful and vindictive.

Although most children with ADHD do not have conduct disorder nearly all children with conduct disorders have ADHD. Children with conduct disorder (CD) show a repetitive and persistent pattern of behavior in which the basic rights of others or major societal norms or rules are ignored or violated. Children with CD are often aggressive, destructive of property, and they lie and steal. About half of children with CD show these same tendencies as adults. ADHD with CD (ADHD-CD) is more severe than ADHD alone. Therefore, most physicians feel it should be treated vigorously at an early age (Wender 2000, 33). For children with ADHD-CD who continue to have problems in adolescence and adulthood, studies show that a combination of treatments for ADHD may be more effective.

Studies show that untreated children with ADHD who are primarily hyperactive are less likely to finish high school or go on to earn higher degrees. Studies also show that children in the hyperactive group are more likely to own small businesses and work independently. In addition, children with primary hyperactivity had lower levels of social functioning, lower self-esteem, worse driving records and higher rates of police arrest (Solanto 2001, 22).

Early studies show a high rate of substance abuse (primarily marijuana) in individuals with ADHD compared to control subjects. Substance abuse was also higher in individuals who had comorbid conditions of antisocial personality disorder or conduct disorders. Follow-up studies by the National Institutes of Health show that children who are treated for ADHD with psychostimulant medications are less likely to abuse drugs in later life than children with ADHD who do not receive medical treatment (NIDA InfoFacts 2009).

Comorbidity refers to the co-existence of one or more disorders in addition to the original disorder. Many studies have documented high rates of other behavioral disorders in individuals with ADHD, especially among individuals in subtype CB. Studies show that 30–50 percent of individuals with ADHD have oppositional defiant disorder (ODD); 25 percent have comorbid anxiety; and 15–75 percent have mood disorders (Solanto 2001, 10). Many individuals with ADHD are reported to also have antisocial personality disorders (ASD), which causes a higher risk for self-injurious behavior (Soreff 2010). Some individuals with ADHD also have autism spectrum disorder.

Comorbid disruptive behavior disorders are less likely to be seen in individuals with the IN subtype of ADHD. Overall, children with ADHD are more likely to have learning disabilities although the specific rates show a great variance. Comorbid anxiety is also common in ADHD and may be related to chronic negative feedback and academic and social failures. Depression coexisting with ADHD appears to run its own independent course.

For many years, ADHD was thought to be a childhood disorder. In the early 1970s, the psychiatrist Paul Wender described ADHD as a chronic condition sometimes persisting through adulthood. The DSM-III recognized that ADD, as it was called then, might persist into adulthood as attention deficit disorder, residual type (ADD, RT). However, there was little data about adult ADHD disorder and no clear diagnostic criteria were given. Consequently thirty years ago, adult ADHD was considered rare and its existence was questioned. Today, adult ADHD is frequently seen and its diagnosis is based on both current behavior and childhood behavior.

In his 1995 book on ADHD in adults, Wender explains that although adults with ADHD may or may not have been diagnosed with ADHD as children, symptoms in adult ADHD always start at an early age (Wender 1995, 21). The most common symptoms of adult ADHD include depression, hot temper and inability to cope with everyday stresses. The Utah Criteria for ADHD in adulthood require the continued presence of hyperactivity and attention problems and 2 of 5 symptoms (affective lability, hot temper, disorganization, excessive sensitivity to stress, and impulsivity).

Studies of adult ADHD have shown that differences in the expression of symptoms are seen in men and women with adult ADHD. The loss of their sense of internal locus in girls with ADHD may cause symptoms that are magnified in adulthood by a sense of self-ineffectiveness and low self-regard. Some women may feel that circumstances regarding life choices are out of their control.

The expression of symptoms in women is also subject to differing, lingering cultural expectations that may be especially intrusive for middle-aged women. Despite changing societal mores, the demands of childcare still fall on mothers. These demands, which require a high level of organization, may be particularly difficult for women with ADHD and their symptoms may be exaggerated in the face of such demands (Manos 2005).

In recent years many reports in the medical literature and on Internet bulletin boards and forums describe adults diagnosed with ADHD in their 20s through their 60s who report that their lives have improved now that they have been diagnosed and are receiving medical treatment. At a number of detoxification centers around the country, physicians are reporting that a high number of their cocaine, heroin, and alcohol addicts have untreated ADHD for which they have been self-medicating.

In 2004, Dr. Olivier Ameisen, a French-American cardiologist from the Weill Cornell Medical College of Cornell University, discovered that his alcoholism was the result of a dopamine and gamma-amino-hydroxy-butyric acid (GABA) deficiency that responded to treatment with the anti-spasmodic drug baclofen. Baclofen is currently being studied in clinical trials for cocaine addiction. The psychostimulant drugs such as methylphenidate and Adderall used to treat ADHD work by increasing dopamine levels (Ameisen 2010). Off-label, baclofen has been used to treat ADHD. Clinical trials are needed, however, to determine if baclofen has the efficacy of stimulant drugs.

Symptoms in adult ADHD can lead to unstable relationships, poor work or school performance and low self-esteem. Common symptoms in adult ADHD include difficulty focusing or concentrating, restlessness, impulsivity, difficulty completing tasks, anxiety, disorganization, hot temper, mood swings, poor coping skills, short-lived, sudden anger, low stress tolerance and difficulty reacting to stress. Although adults with ADHD tend to have explosive tempers, they rarely nurse anger or brood. In explaining the temperament of adults with ADHD, Dr. Paul Wender writes that the ADHD adult has no desire to violate societal norms. Rather, he has trouble conforming to them (Wender 2000, 167–8). For instance, adults with ADHD can find it difficult to prioritize and they may show signs of impatience waiting in line or dealing with heavy traffic. Most adults can occasionally have symptoms of ADHD but they do not receive a diagnosis of ADHD unless symptoms are persistent and interfere with two or more areas of their life.

About one-third of children with ADHD outgrow their symptoms; another one-third go on to have mild symptoms; and another one-third go on to have significant symptoms through adulthood. About half of all adults with ADHD also have at least one other diagnosable mental health conditions, such as depression or anxiety (Mayo Clinic Staff 2010).