CHAPTER 14

BATTLE FOR CARROCETO

Anzio Beachhead, February 8–10, 1944

For the 5th Grenadier Guards and H Company the night seemed to last forever. “The most encouraging stutter of the H Coy’s Browning was heard all night,” mentions their War Diary, “but the few weapon pits on the top of the gully; that is to say on the West bank—and some others on a large mound in the middle of the gully were evacuated, since the Spandaus were higher up and almost drilled the occupants out of them.”337

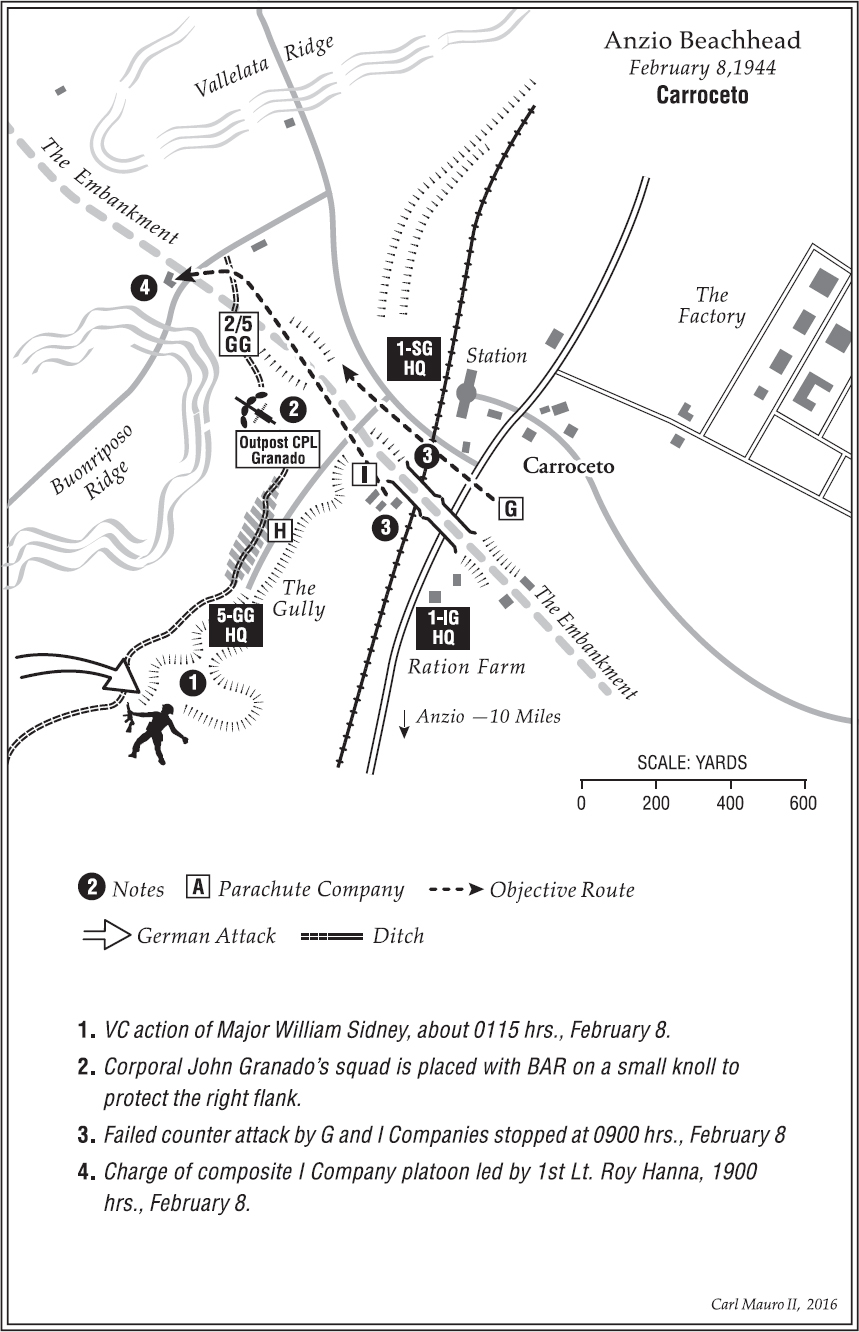

The stretched ditch north of the Gully in the direction of the Embankment was now defended by H Company and the Gully itself by the remnants of the Grenadier Guards Headquarters Company and their Support Company, led by Maj. William P. Sidney. “Because we found not friendly units on our right, our flank was vulnerable,” recalled 2nd Lt. Megellas. “I placed the Browning automatic rifle (BAR) man, Corporal John Granado [and his squad], on the high ground to our right with orders to dig in and shoot anything that approached from the direction of the enemy.”338

These positions were to give the Germans the impression of a strong defensive position west of the Via Anziate, but it was pure bluff. “If the enemy had broken through at this point,” according to the 1st Scots Guards history, “they would have cut off not only the remnants of the Grenadiers, but the American parachutists, the Scots Guards in Carroceto, and the London Irish Rifles in the Factory, as well as opening a passage to the tanks, which had been heard moving up in readiness behind the German infantry.”339

This left the Grenadiers at the climax of the battle with Capt. Martin’s No. 2 Company withdrawn to an enfilade position on the Embankment; the few men of Headquarters Company and Battalion Headquarters in the Gully, who now occupied the center of their position; and H Company, which had been hurriedly brought up on the right of Battalion Headquarters. Between their thin defensive line and the Via Anziate, nothing remained to stop the attack of the German 147th Grenadier Regiment.

Major Sidney and a handful of men of his Support Company held the crucial part of the Gully opposite a place in the Ditch from where the German infantry could easily enter the Gully. He moved forward on his own, armed with his tommy gun, and stood upright in the face of intense fire. Sidney held off the Germans of Leutnant Heinrich Wunn’s 7th Company, 147th Grenadier Regiment, until his gun jammed. He moved back to the edge of the ramp leading down into the Gully and started to throw grenades at any Germans who came in view. Two of his Guardsmen were priming these grenades as quickly as possible and then passed them on to him.

Suddenly one of the grenades exploded prematurely and killed one of the two Guardsmen and wounded Maj. Sidney in the legs and forehead. Again Sidney was wounded in the face by a German stick-grenade just as his men came forward to his assistance and prevented a German break through. Sidney was later awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest British medal, “for superb courage and utter disregard of danger.”340

At 0330 hours on February 8, the Germans carried out another all-effort infantry assault on the dwindling group of H Company troopers and Grenadier Guards in the Gully. The adjutant of the Grenadier Guards, Capt. The Lord Stanley, sent the following message to Brig. Murray in 24th Guards Brigade Headquarters: “Nothing heard of No. 1 Company for forty-five minutes. Nos. 3 and 4 Companies believed overrun. Ourselves surrounded, and there is a German on the ridge above me throwing grenades.”341

The second German attack to cut the Via Anziate south of Carroceto was repulsed by well-aimed, close-range small-arms fire, grenades, and the precisely aimed requests for fire support of the artillery officer attached to the Grenadier Guards. Their Regimental History continues: “As the light strengthened, the German attacks died down. Looking around them at dawn, the Grenadiers saw the ground in front of them littered with German corpses; and over on their right the men of No. 2 Company moving unconcernedly about the Embankment. The latter had passed a difficult night repelling the central German column; being cut-off from their own headquarters, they had drawn food and ammunition from the Scots Guards on their right. The North Staffordshires had been completely overrun, and the Irish Guards had taken their place.

“Of the Germans immediately facing the Grenadiers there was little sign. Whenever a head appeared on the Buonriposo Ridge a British or American rifle would open fire at once, but during the hours of daylight there was no renewal of the attack.”342

The attack of HQ and G companies stalled as they ran into intense Germans small-arms and machine-gun fire from the Buonriposo Ridge. Lieutenant Colonel Freeman decided to consolidate his position around 0900 hours and wait for the evening, before trying again.343 He had meanwhile to decide the officer to whom he would assign the command of I Company, as 2nd Lt. Blankenship had been wounded late on February 7.

The writer of the 5th Grenadier Guards War Diary recorded that “during the day [1st] Lieutenant La Riviere, the Commander of H Company of the parachutists reported to us that two other companies of his Battalion were between the road and the ridge just to the west of us, but that they found it impossible to move nearer down the forward slope because of the heavy small arms fire … After a time the telephone cable was cut between these two companies and H Company and was never repaired.

“Whilst there were no actual attacks by the hours of daylight there was a considerable exchange of small arms fire. Drill Sergeant Armstrong spent most of the day shooting at odd Germans and shot, if anything, a little better with his own Short Lee Enfield rifle than did the two American snipers, who were blessed with extremely good sniper’s sights.

“If anything, the battle during the day was conducted a good deal more intelligently on our side than that of the Germans who left a sort of outpost screen of riflemen and snipers all across the front. People could be seen examining us through binoculars, but even so they must have been grossly deceived as to our actual strength which was 29 Grenadiers, 4 of whom had been wounded during the previous night, and about 45 Americans … However any movement here or in the bottom of the gully was visited with an unpleasant volume of small arms fire, and it proved impossible to get on top of the gully in daylight to secure any identifications …

“It had been a cold and clear day, but towards the evening the clouds began to roll up and by six o’clock it had begun to rain. Our ditch speedily became a running stream and in view of this the Commanding Officer decided—before he slipped away to see Brigade—to move the [wireless] 22-set back into the IP tent where it would at least be possible to write messages in the dry.

“At the same time our defences were reorganized. The top of the gully and both entries to it had to be held, to avoid a repetition of the German grenade throwing. Accordingly Lieutenant J.A. Lyttleton and Drill Sergeant Armstrong and six men were stationed on the floor of the southern end; Lieutenant W.S. Dugdale, MC, and Lieutenant C.C.P. Hodson with seven men and the only workable Brengun held the entry at the northern end; and Lieutenant G.W. Chaplin with two Guardsmen and six Americans [Sergeant Clement A. Haas’ squad] were placed along the top.

“Just before these positions were taken up there was a considerable and mystifying 25-pounder smoke screen on the ridge in front of us. It was a very good one. When it cleared we beheld the Germans again in force all along the top and the Spandaus began once again to search our positions. The American Browning replied in just as definite terms and while the enemy appeared to be preoccupied with this, the defenders got into position. There was one unhappy incident. One of the group of Americans [Pfc. Harry L. Seitz] on top of the gully stood on the edge and looked down. In the half darkness a guardsman below took him for a German and at once shot him with a Tommy gun, wounding him severely in the stomach. The group of Americans was changed for four more, and two signallers from our Signal Platoon made up the numbers again.”344

Sergeant Haas recalled that he, Cpl. William Eberhart, Pfc. Seitz, and Pvt. Louis Holt were sent “to a position on a small knoll to the left and front of H Company. As soon as we started digging in we came under German artillery and small ammo fire. While were digging, Seitz who was between Eberhart and me, was hit by fire from a German [British] automatic weapon. He was hit badly in the stomach and chest. Eberhart and I pulled him behind the knoll and laid him on a blanket and managed to carry him back to H Company and from there to the [3rd Battalion aid station]. The Battalion doctor said that Seitz would be sent back to the evacuation hospital and then to Naples. He told me he thought Seitz would make it. We later learned that Seitz died of complications from his wounds on February 20.”345

At dusk lieutenants La Riviere and Megellas left the ditch and moved to the Buonriposo Ridge. “Rivers and I crawled up the high ground to our left to recover Sergeant Radika’s body. With Rivers lying on one side of the body and me on the other, we dragged it facedown by the harness straps to our position.”346

“By the time everyone was in position it had already been raining hard for an hour,” the Grenadier Guards War Diary continues, “and the cold was dreadful. It was impossible to keep dry or warm, and the rain turned to sleet. To cap this the Germans launched another attack on the gully. It was preceded by five minutes very intense shelling which fell unto the cliff and into the gully without inflicting a single casualty.”347

Meanwhile 1st Lt. Roy M. Hanna was summoned to Freeman’s command post for a briefing about a new counterattack: “At the time I was in command of the 3rd Battalion Machine Gun Platoon that was in support of Company G that was engaged with the enemy on another flank. Lieutenant Colonel Leslie G. Freeman transferred me to Company I as the temporary commander. Company I normally had eight officers and about 130 enlisted men. When I was ordered to take over Company I all eight officers had either been killed or wounded and taken to rear hospitals and about 45 enlisted men remained on the line.

“I had 1st Sergeant [Curtis] Odom withdraw about 20 men from their front line position and have them lined up behind a railroad embankment, while I went to the second floor of the headquarters building and, with field glasses, surveyed the situation and made my general plan of attack.”348

Odom decided to pull back the 3rd Platoon, led by S/Sgt. Louis E. Orvin, Jr., and sent a runner to the 1st Platoon. Private Francis Keefe and two of his buddies were in a foxhole “when [1st] Lieutenant Hanna sent out the runner to contact everyone in different foxholes. We all met Lieutenant Hanna and he told us the situation that H Company had been cut off and we were going to attack the enemy positions and make contact with them.”349

While I Company prepared to attack astride the left side of the Embankment, G Company prepared to attack on the right side, closer to Carroceto. First Lieutenant Hanna found I Company assembled near the railroad track around 1900 hours when the attack started: “When I joined the men along the railroad track I had them ‘Fix Bayonets.’ This, because I thought we might have some hand to hand contact. I don’t believe any use of bayonets was necessary during this mission.”350 First Sergeant Odom was instructed to remain at the company CP to supervise the twenty or so men who did not participate in the assault.351

Private Keefe recalled that Pfc. John J. Gallagher and Sgt. Marvin C. Porter were wounded when they reached a German outpost: “The ground had sloped up and it got much higher as we hit the German outpost. The two Germans that were at the outpost threw their hand grenades and two of our men were wounded … The opposition was eliminated; their position was near what looked to me to be a large brick oven that the Italians used for baking outdoors. I was towards the rear when we got close to it, the men in the front went around it and started around the left of the oven. It was at that time that all hell broke loose.

“This all occurred in a matter of seconds. On the right hand side an enemy machine gun opened up. The machine gunners position was about 50 yards from the oven’s position. It was firing where the attack was taking place. I told ‘the Greek’ [Sgt.] George Leoleis that I was going to go up and fire a grenade at him …

“The enemy gun went silent. I turned around and started running back and I yelled ‘Greek, I am coming back in.’ The enemy must have heard me even with all the firing that was going on, because most the firing was on the left, when I got back behind the oven the enemy’s machine gun came back to life. It started firing and the bullets were hitting the oven and they were bouncing off the oven. You could see the tracers going up in the air, lucky me.

“The enemy must have realized they were wasting bullets on a large object because they turned their gun from their position to the left more away from the oven and the bullets were going off away from where the attack was taking place. I know I didn’t silence the machine gun for good with my grenade but was successful to have them firing at none of us.”352

Unknown to Keefe, 1st Lt. Hanna had been hit: “At the time I was wounded I was running in a crouched position out a hedgerow. The bullet entered between two ribs on the upper right side of my rib cage into the top part of my lung. From here it passed down through the lung through the diaphragm and out between two ribs of the lower back. It didn’t touch a bone and missed several arteries. The lung collapsed and filled up with fluid causing oxygen starvation resulting in me passing out. I never felt myself getting light headed I just simply woke up on the ground. This happened three, maybe four times during the attack.”353

On May 10, 1944, Headquarters Fifth Army acknowledged the award of “a Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism in action” to 1st Lt. Hanna. The citation reads as follows: “During a long and sustained attack against strong enemy positions a company suffered heavy casualties and lost its combat effectiveness. Because of the critical nature of the situation, First Lieutenant Hanna was ordered to reorganize the company and launch a diversionary attack to lessen pressure on another unit attacking the objective from the opposite direction.

“First Lieutenant Hanna successfully withdrew the elements of the company still in contact with the enemy, reorganized the unit and led his men in an assault against overwhelming enemy odds. While exposing himself to heavy enemy fire in order to lead his unit, he received a rifle bullet through the chest. In spite of his wound, First Lieutenant Hanna personally led the attack until he collapsed unconscious on the field. His courageous performance and his gallant leadership inspired his men to press the attack and to complete the mission successfully.”354

The Italian Government awarded 1st Lt. Hanna the Croce di Guerra al Valor Militare [Military Valor Cross] in September 1945. Although no citation was sent along with the medal, it must be assumed that it was given in recognition of his action near Carroceto. According to 1st Lt. Hanna, he “was awarded the Purple Heart, and given the citation of the Distinguished Service Cross that was actually earned by about 20 brave men.”355 Hanna was meanwhile carried on a stretcher to the road: “By the time the men got me back to the road on a stretcher ready to be loaded on the British ambulance it was just getting dark. I remember zipping my jacket open and enjoying the feel of the cold rain on my hot chest. The ambulance trip back to the British tent hospital was during pitch dark conditions. It traveled with black-out lights and kept slamming on the breaks as they came to holes in the road from artillery shells. This is the first pain I remember having as the fluid shifted back and forth in my lung.”356

Private Keefe rejoined Sgt. Leoleis and noticed that while “the firing continued, [1st] Lieutenant Hanna was put on a stretcher and we started to move back toward our original positions. At that time [Pvt. Robert L.] Fetzer had been seriously wounded by a mine. I was part of the stretcher bearing that had Lieutenant Hanna on it. He was talking but only he knows what he was saying. We were glad he was awake. We also got Fetzer’s body out.”357

There was still radio contact between the 5th Grenadier Guards and the 24th Guards Brigade Headquarters, where Lt. Col. Huntington had stayed. The War Diary sums up what followed: “At 0210 the Commanding Offficer spoke from Brigade and gave us the by no means unwelcome orders to re-establish Battalion Headquarters on the railway embankment, saying that as many vehicles as possible were to be evacuated. The bed of the gully was by now a sort of lake and the track down into it (or up out of it) was as slippery as a piece of ice. Lieutenant J.A. Lyttleton made a recce of the vehicles and reported that the only ones which could possibly get out were one carrier, one jeep and Major Greig’s scout car. These vehicles were marshalled at the entrance to the gully and the Americans warned of the forthcoming manoevre. All men were withdrawn from the defence position and at about 0315 the whole of Battalion Headquarters filed out of the southern end of the gully, across the muddy fields on to the main road, and then north again to the railroad embankment.”358

To their amazement the British moved to the Embankment without receiving any enemy fire and arrived at the culvert where they joined their Regimental Aid Post. For the Grenadier Guards the ordeal had ended—for H Company it had not. A messenger from G Company appeared in the ditch and told 1st Lt. La Riviere that I Company had successfully carried out a diversionary attack. H Company was ordered to fall back across the Via Anziate road while I Company would provide overhead fire. Word was being passed to pull back when a runner reported Cpl. Granado’s outpost on the small knoll was empty. What had happened?

Private First Class Neil A. Nilson recalled that “I had thrown all my grenades. It was night. There were flares all around us. We ran out of ammunition. [You] can’t fight without firearms.”359 Around 0300 hours an American voice called up to them from the Gully: “Is anybody alive?” They answered, “Come on up and find out!” But the runner disappeared and then the Germans ordered them to surrender. Nilson raised his hands from his foxhole.360 A few days later he was placed with forty-five POWs in a boxcar that moved to Germany: “There was a barbed wire across an open window in our car. Some of the men removed the barbed wire. Three men escaped! So we were moved into another boxcar that had 47 guys. Now we were with more than 80 in one boxcar. A nail keg was our latrine. A fourth of a loaf of bread was our food for six days. It was cold. We went through the Alps.”361

His mother first received a notification from the War Department on April 13 that her son was missing and shortly afterwards a regimental report that he was believed to have been killed: “Private Nilson, at approximately 0300 on February 9, 1944 in the vicinity of Carroceto, Italy was a member of a Machine Gun Squad situated on the Company’s right flank. A heavy concentration of enemy fire necessitated the Company’s withdrawal, a runner was sent to determine the delay of Private Nilson’s squad. In moving to the rear position, the runner attested all members of the squad had been hit by an enemy shell and did not answer when called. Removal of the bodies during the barrage was impracticable and it is believed that Private Nilson was killed.”362

Mrs. Nilson refused to believe Neil was dead and thirteen days later a telegram from the Foreign Broadcast Intelligence Service was delivered: “The name of Neil Nilson has been mentioned in an enemy broadcast as a prisoner in German hands. The purpose of those broadcasts is to gain listeners for the enemy propaganda which they contain but the army is checking the accuracy of this information and will advise you as soon as possible.”363

Corporal Granado and privates Richard R. Ranney, William W. Reiley, and Paul J. Trujillo also ended up in Stalag IIB. Granado remembered they were manning their machine gun when suddenly “the Germans appeared to be everywhere, infiltrating all around us. We had no contact with the Company and were unaware that we were pulling back. We never got the word. The Germans overran the outpost and took us prisoners. We were taken back through the attacking forces and German lines. We passed through what had been the British lines where we saw a lot of dead British soldiers. A lot of them were killed in their foxholes. The Germans took us back to a big farmhouse and from there to a POW camp.”364

He later received the Distinguished Service Cross: “Corporal Granado, with an automatic rifle team was manning an outpost on a high knoll approximately 50 yards to the right of his company’s right flank, when an enemy counterattack isolated his company from the rest of the battalion. His company received the order for withdrawal to a new defensive position.

“Corporal Granado elected to remain in his outpost position by himself, continuing to fire on the onrushing enemy with his Browning Automatic Rifle. In doing so, he drew heavy enemy fire on his position, thereby enabling his company to withdraw to its new defensive position without the loss of a man. Corporal Granado’s decision to remain in his perilous position, in utter disregard for his own life, was heroic and contributed materially to the later success of his unit.”365

Private George T. Wells was wounded when an enemy shell exploded nearby his foxhole and shrapnel broke his right elbow and knee. Wells “got up to walk and my leg wouldn’t work so good, so I lay down. I had no pain after I was hit and I went to sleep for a few minutes. Then I crawled about 75 yards up a hill, almost to the crest and then dropped off to sleep again. The Jerries just over the hill were watching me.

“About 0200 or 0400 two Jerries came up carrying a blanket. One looked down, smiled, and patted me on the cheek like a kid. I had expected to be kicked around a little. ‘Vare are you wounded?’ the Jerry asked and I pointed to my leg and side. They put me on the blanket and carried me back to their Command Post and then on back to an aid station where I was placed under an arch. I sweated it out for about an hour as our artillery was blasting all around me. They took care of the Germans first and I laid out there and about froze to death for about an hour. Finally they took me in the house, looked at the bandages that had been put on a few minutes after I had been wounded, but didn’t do anything for me and sent me farther back.

“At a hospital, the Germans put me to sleep, got out some of the scrap iron, and put a cast on my arm and leg, and then I was sent to a beautiful hospital in Rome where I remained for about three days. A young German in the room with me in Rome paid for having me shaved and also gave me cigarettes as I had no money … They were good to me. I was surprised.”366

Wells was fortunate in late January 1945 when he was repatriated on the Swedish MS Gripsholm after a major prisoner exchange on the German–Swiss border. He arrived in Jersey City on February 25.

Three men of Granado’s squad were killed: privates Marvin K. McMillen (February 7—although this date could be wrong), Malverne N. Moyer (February 9), and Vincent V. DeNard (still missing in action). Moyer was killed by a German grenade in his foxhole—probably the same that wounded Wells. Daniel Marvin McMillen was born on February 11, 1944, in Cincinatti, Ohio, and would never get to know his father.

Corporal Samuel J. Cleckner was awarded the Bronze Star for his actions during a strong German attack where he “voluntarily and without regard for his personal safety, remained in an exposed position to cover the withdrawal.” With his rifle, “Cleckner repelled every attempt by the enemy to advance. Even after being seriously wounded … Cleckner, with heroic tenacity, continued fighting until every man had reached new positions. As a result of his brave determination and heroic conduct, the gravity of his company’s position was relieved and the lives of many of his comrades saved.”367

Second Lieutenant Megellas had been wounded in his arm and after a stop at the battalion aid station was evacuated by ambulance to a field hospital. At “Hell’s Half Acre” hospital tents, like the entire beachhead, remained under constant German shelling. Eventually he was loaded on an LST [Landing Ship, Tank] bound for the 45th General Hospital in Naples, far behind the frontlines. While talking to the wounded soldier who lay next to him, Megellas suddenly learned that he was a German: “My first impulse was to grab him by the throat and change his status from WIA to KIA, but my better judgment prevailed. He and I were both in the same boat: survivors of a bloody battle. There was a difference, however; the war was over for him, but I would return to the battlefield when I recovered.”368

After H Company had been reported safe, I Company started to withdraw, having lost Pfc. Walter Komula killed. “There were quite a few flares going off from the German positions,” recalled Keefe. “It’s a wonder we didn’t have more casualties. The medics took over the task of getting [1st] Lieutenant Hanna to Captain Kitchin. The rest of us were around the I Company CP. We were going back to our old foxholes, and of course it started to rain again.”369

Lieutenant Colonel Huntington was tragically killed later on February 9 standing in the culvert under the Embankment. German machine-gun fire hit him through the chest and he died instantly. But despite the death of Huntington, the effort of H Company had not been in vain. Their timely arrival at the Gully prevented the Germans from reaching the Via Anziate and destroying the Grenadier Guards. For his bravery and leadership, 1st Lt. La Riviere was awarded the British Military Cross: “During the night 7/8 February the 5th Battalion Grenadier Guards were heavily attacked by the Germans. Lt. Riviere and his Company were sent to reinforce the Grenadiers and on his arrival he found only one Company and 27 of Battalion HQs still in existence. During that night and throughout the next day there were several more attacks by the enemy and it was largely due to the assistance given by Lt. La Riviere and his Company that the attacks were withstood.

“At 2000 hrs on the next night Lt. La Riviere was told that he might withdraw his Company but knowing that the enemy were still in close proximity and realizing that the Battalion would be unable to withstand further attacks on their own, he voluntarily remained with the Grenadier Guards. Later that night the position was again heavily attacked but all attacks were beaten off.

“At 0300 hrs the Grenadier Guards were ordered to withdraw and, although the enemy were within 20 yds of the position, the covering party provided by Lt. La Riviere enabled the Battalion to withdraw without loss and to extricate a considerable quantity of valuable equipment. Throughout the action the soldierly bearing and courage of Lt. Riviere and his company were a source of constant admiration to all ranks of the Grenadier Guards.”370

On February 10 around 1000 hours the H Company CP just east of the underpass was suddenly shelled. First Lieutenant Sims, S/Sgt. William C. Kossman, and Pfc. John A. Bahan dove into a slit trench next to the building. “When the shelling started I scrambled out the back door of the CP and dove into a foxhole,” recalled Sgt. Clement Haas. “I was about 10 yards away from the slit trench that Lieutenant Sims, Sergeant Kossman and Bahan were in. About a minute or two later a German artillery shell hit the corner of the roof and sent shell fragments into the slit trench. I was not hit. I ran over to the slit trench to get them out. I went with them in a jeep to the Battalion Aid Station. Not long after we got to the aid station Kossman died. Bahan died the next day.”371

For another week the 3rd Battalion would remain attached to the British 1st Infantry Division. By the time they—and the remnants of the British battalions—were withdrawn on February 16, only 1st Lt. Elbert F. Smith and twenty-five men of G Company, lieutenants La Riviere and Sims and 40 enlisted men in H Company, and a similar number in I Company were left. Headquarters Company had about fifty officers and men left. The entire 3rd Battalion numbered little more than a rifle company in total, but had been instrumental in stopping the German counteroffensive.