In the last chapter we saw that residential mobility between neighborhoods formed a connective structure, a weblike flow of movement that could not be reduced to the compositional characteristics of individuals. This chapter pursues a conceptually related claim on the idea of the interlocking city. I propose that ties among key institutional leaders form systematic connections of influence within and across communities, and that the emergent structure of these networks bears on our understanding of how cities work. Information exchange and institutional ties among decision makers are a crucial mechanism for getting things done, even if on an everyday basis they might be invisible to the casual observer. My goal is thus to uncover this otherwise hidden structure of elite social action and then connect it back to both internal community characteristics and interneighborhood networks of residential exchange.

To do so, I exploit another original effort of the Chicago Project that I briefly introduced in chapter 4. The Chicago Key Informant Networks Study (hereafter KeyNet) advances the comparative study of social networks by directly probing the ties between community elites and other influential actors. Unlike the vast majority of network studies in single settings, the KeyNet’s design is uniquely tailored to an analysis of how leadership structures vary across different communities. Although a pioneering set of community studies has investigated in rich detail the patterning of elite social influence, prior efforts were constrained by a focus on a single community or network or, at most, on a handful of areas.1 More generally, there is an irony in the literature on social networks—for all the emphasis on “structure,” most of the empirical research has focused on interpersonal influences and individual outcomes. That is, the behavior or attitudes of individuals are seen as influenced by others in one’s network, what is known as the social influence model. A number of network approaches to social structure makes inferences to the network as a whole (e.g., a classroom or an organization), but rarely are multiple contexts or variability across network structures at issue and almost never in concert with direct measures of social processes and mechanisms.2

The KeyNet design addresses these concerns and permits a continuation of our bird’s-eye view of the relative position of neighborhoods in the overall social structure. As noted in chapter 2, the overwhelming legacy of the Chicago School has been the community study, with its attendant focus on intracommunity dynamics and the between-neighborhood study of variations in local social controls and other internal neighborhood processes in the social disorganization tradition.3 Across the years, urban scholars have proposed but never fully realized an alternative program of research whereby neighborhoods are regarded as pieces of a larger whole of an interlocking city or metropolis. In this chapter I meet this challenge by studying how social networks link leaders representing the institutional fields that organize much of contemporary social life. My approach to realizing a more holistic vision includes the study of relations both within and across neighborhoods—not merely as a function of geographical distance but of the interlocking and cross-cutting networks that connect elites, organizations, and ultimately communities throughout (and beyond) Chicago.

The KeyNet study is a large-scale and complex effort that was motivated by a host of questions that could sustain a standalone book. I hope to build on the findings in this chapter to write such a book in the future, with a focus on the social context of governance. For now, however, I strive to be parsimonious by subjecting the KeyNet study to a focused set of five analyses that are directly motivated by the present book’s theoretical framework and the results of preceding chapters. My strategy is to first highlight four basic aspects of Chicago’s leadership connections: (1) how institutional domains of leadership are interconnected, (2) how the structure of elite networks—such as the density of ties and the centrality of communities in the overall network of ties—varies across communities, (3) the nature of stability and change in network properties of leadership over time, and (4) whether leadership network structures are explained primarily by the demographic and economic makeup of the community or instead are more fundamentally related to social processes like collective efficacy and a community’s organizational life. These four questions cut to the core of our understanding of the community-level context and dynamics of leadership and influence.

Fifth, and perhaps most important, I take a look at how the structure of leadership is related to community wellbeing, and I pursue further the relational approach of the previous chapter by hypothesizing that interneighborhood migration flows are directly related to network flows defined by leadership ties. I argue that if such a link exists and cannot be explained by spatial proximity, demography, or economic status, it would support the ongoing thesis of a higher-order social ordering of the city that simultaneously takes into account individual actions and the composition of each community. Overall I argue that despite the very different empirical terrain, the realization of individual choice—in this case, by elites—is governed by the same systematic properties of the social structure that govern migration flows.

KeyNet-Chicago

The KeyNet was designed to examine community leaders or experts who, based on their position, have specialized knowledge of, and responsibility for, community social action. In a real sense the key informants I study are elite, a group of persons who by virtue of their position exercise power or influence in the community. They are also considerably more educated and make more money than the average citizen; for example, almost half (46 percent) of the key leaders in 1995 had a college or graduate degree, compared to less than 20 percent of the representative sample of adults in Chicago in the same year. We tend to think of elites or leaders only at the very top (presidents, mayors, corporate chieftains), missing the layers of action just below the surface that often do the heavy lifting. Not everybody can be a Mayor Daley, for example, and he is certainly powerful. But his power is nothing without a connective structure that reaches deep into multiple communities and that depends on people who can command action. It is not just the famous aldermen that are at issue, but police captains, school principals, business leaders, ministers, and more. It is these sorts of actors that I study and without whom the workings of Chicago’s social order would stall.

The key informant method draws on a distinguished history in cultural anthropology and organizational sociology of using key informants to report on the social and cultural structure of collectivities.4 The use of positional informants to gather quantitative data on context has also proven to be a reliable, although underutilized, methodology in the social sciences.5 In the present chapter, I focus on the connections of community leaders within and between communities from a positional perspective, using informants to define, through both nominations of key actors in their network and through snowball sampling, the communitywide context of social organization. KeyNet is a panel-based study that had two major components.

Panel I. The initial design was based on a systematic sampling plan that targeted six institutional domains. We began with the eighty neighborhood clusters in the PHDCN that have been studied throughout this book. These clusters are representative of the city by design and are located in forty-seven of the city’s community areas. Because of the sampling design, these forty-seven areas are in effect representative of the city’s seventy-seven areas. Targeted domains included education, religion, business, politics, law enforcement, and community organizations. In most cases the jurisdictions of these domains extend beyond the neighborhood clusters, and so the KeyNet sampling design targeted the larger community area within which the clusters were embedded. As described in earlier chapters, in Chicago most leaders and organizations representing the six institutional domains recognize the boundaries of the city’s community areas, which average about thirty-seven thousand residents, and many rely on them to provide services.6 The sampled communities ranged from ethnically diverse Rogers Park on the Far North Side to black working-class Roseland on the far south, from exclusive Lincoln Park to the extreme poverty of West Garfield Park, from Mexican American (Little Village/South Lawndale) to Puerto Rican (Humboldt Park), and from white middle class (Clearing) to black middle class (Avalon Park). The Loop was also included.

The design required the construction of a geocoded list of over ten thousand positional leaders in Chicago from public sources of information (e.g., phonebooks, directories of businesses and services). Of these, 5,716 were located in the forty-seven sampled community areas. Target informants were defined by the nature of who they were, what they did, and where they were located. Examples of key informants by domain include:

• Education: public/private school principal; local school council (LSC) president

• Business: community reinvestment officer (banking); realty company owner

• Religion: Catholic priest; Protestant pastor; mosque imam; synagogue rabbi

• Law enforcement: district commander; neighborhood relations sergeant

• Politics: alderman; ward committeeman; state representative; state senator

• Community organization: tenant association president; health agency director; community social service manager

Approximately 2,500 cases were sampled, stratified by community and domain before random release for study, with 10 percent turning out to be ineligible (e.g., moved, business closed). NORC at the University of Chicago carried out data collection in 1995, completing 1,717 interviews with sampled leaders in official positions. As seen in the list above, key informants are highly visible actors in the community and easily identifiable, so extreme cautions were taken to protect the confidentiality of data. Occupation alone could identify an alderman, for example.

Following the research tradition established in cultural anthropology and social-network analyses of community influence structures, a “snowball sample” was incorporated as an addition to the original design. We suspected that many of the key actors in a community were new to the position or did not appear on official lists and hence were not sampled. Moreover, some of the influential actors in a community may hold nontraditional positions. To capture the full range of community informants, our interview asked respondents to nominate knowledgeable or influential persons in each of the six core domains of business, law enforcement, religion, education, politics, and community organizations. For the more nontraditional persons who might be able to report on the community, we asked each respondent: “Now, other than the people and organizations that we’ve already discussed, is there anyone else in [COMMUNITY NAME] that we should speak with, to really understand this community? This could include a longtime resident, a leader of a youth club or gang, a mentor of youth in the community, and so on. Who else would you recommend we talk to?” The sampled positional leaders generated 7,340 reputational nominees, about 3,500 of whom were duplicate nominations—the same individual nominated more than once, or a nominee already in the sample. This finding in itself serves as an important validation of the design.

In all, 1,105 reputational interviews were completed, which, when combined with the positional interviews, brings the final sample size to 2,822. The interviews averaged just under an hour in length, and the overall completion rate was a surprisingly high 87 percent of eligible cases.

Panel II. Just as it is not sufficient to study individual development at one point in time, so it is misleading to rely on snapshots of community-level processes—communities and networks change. A panel-based positional approach to the study of community dynamics allows for the measurement of changes in community leadership (e.g., is there a new leader in the same position?), organizational change (e.g., did the institution itself survive?), changes in the dimensions of social-network structure (e.g., the density of ties), and changes in the content of action (e.g., crime prevention, health promotion). I thus designed the KeyNet panel study to capture (a) reinterviews of 1995 leaders still in the same position, (b) new leaders in the same position or organization as in 1995, (c) leaders in newly formed organizations and positions, and (d) where leaders who exited from 1995 positions went. Organizational and positional sampling frames were updated in 2000 and pretest interviews conducted with fifty-two leaders.

The final sample was constructed in 2002 as a random selection of original positional leaders in 1995, stratified by institutional domain, plus snowball sample nominations designed to capture both new organizations and new leaders. To contain costs, a representative subsample of thirty of the original forty-seven communities was selected for the panel sampling frame. NORC at the University of Chicago was selected to carry out all aspects of contacting respondents and conducting interviews. Over one thousand (N = 1,113) interviews were completed over the summer and fall of 2002 at a response rate of 76 percent of eligibles. Approximately 60 percent of the interviews in 2002 were conducted with new respondents holding the same or similar position as the 1995 respondents, indicating considerable personal turnover in a fairly stable network of positions. The final sample yielded an average of almost forty interviews per community, permitting rigorous examination of how leadership network structures vary across communities.

Assessing Elite Networks

I begin by defining a connection (a tie or an “edge,” as it is known in network science) as a nomination that an institutional representative or key informant within a community makes to another individual (“alter”). These ties can be to others within the same community (what I call an “internal alter”) or another Chicago community (“external alter”). Ties can and do extend beyond Chicago as well, as, for example, when a leader of a community organization reaches out to a state senator in Springfield, Illinois—yet another kind of external tie. To establish these kinds of leadership ties, the original KeyNet study developed a modified version of Ronald Burt’s “name generator,” revised by focus groups and then formal pretests in both the 1995 and 2002 studies.7 In our modified instrument each respondent was asked to identify by name the people they went to in order to “get things done” in the community. Up to five names were allowed. We pretested multiple name generators, but this wording seemed to capture for respondents concrete situations when they formed social ties. Also, by not specifying the type of contact (e.g., asking about a “friend” or “well-known acquaintance”) and by not asking for a preset number of contacts (as in, “tell us your three contacts”), we avoided criticisms of commonly used name generators that artificially induce only strong ties or force pseudo-contacts.8 In fact, many of our respondents were isolates and did not name any contacts, information that is directly relevant to the theoretical problem at hand. The names and addresses of each key contact up to five were recorded, along with their position and organizational affiliation.

In 1995, community leaders nominated almost 5,600 alters as key contacts, but, as theoretically expected, there was overlap in these citations—only about 2,050 of the alters were unique individuals. Respondents nominated 2.5 alters on average, and each distinct alter in 1995 was nominated by 2.72 leaders. The pattern of concentration in 2002 was similar, even though the sample size was smaller—for example, the average number of alter citations was a bit higher, at 3 (over 3,000 nominations and 1,275 distinct alters), and each alter was nominated by 2.4 different respondents on average.

Figure 14.1 shows the flow of ties among respondents and nominated contacts in 2002 for the entire city and without reference to geographic location. Arrows denote direct ties and circles represent individuals with size proportional to “indegree,” or the number of distinct ties each person received. The data from 1995 show a similar pattern, but I set that aside in favor of the more recent assessment. At the level of the entire network of individuals, we find a large number of isolated or weakly connected contacts around the periphery (for example, some respondents did not have any contacts) along with a relatively small number of “connectors” in the center who mediate or control much of the action along with a number of cliques radiating outward. There are a number of major players both at the center and in subgroups, including what we might jokingly call “Mr. Big” in the absolute center, but who in fact is big, receiving a disproportionate share of network ties (and who shall remain anonymous, like all leaders).9

Although networks like those in figure 14.1 are usually the main story, my major concern is the community-level and temporal variability of ties. Recall the stark differences between the community of Hegewisch and South Shore introduced in chapter 1 (see fig. 1.4). The former appeared much more “cohesive” than the latter in the picture. I describe here how I capture these differences more formally and for all communities. Because of the systematic and replicable sampling procedures, the KeyNet design allows me to construct network measures for each of Chicago’s communities in parallel fashion for both the 1995 and 2002 studies, permitting both comparative and temporal analysis of network structures over time. For simplicity and on grounds of parsimony, I first focus on the density of elite ties and the centralization of the leadership network.10 Density captures the idea of cohesion among ties, specifically the proportion of all possible ties that actually exist among key informants. The opposite of cohesion is fragmentation of ties into cliques. In his seminal paper on weak ties, Mark Granovetter trained his analytic sights on Boston’s West End neighborhood, which was unable to fight off urban renewal in the 1950s. Herbert Gans attributed its failure to mobilize mainly to subcultural and political forces, but Granovetter suggested that the ties in the West End lacked structural cohesiveness, a network phenomenon that could only be viewed from what he called the “aerial” perspective—“the local phenomenon is cohesion.”11 In other words, there might be strong ties within interpersonal cliques, as displayed in figure 14.1 or perhaps as in the “urban village” ideal of tight-knit neighborhood groups, but little cross-group or extralocal ties and thus fragmentation at the level of the city’s political or social structure.12 These important ideas have not been systematically investigated at the aerial level across multiple communities over time.

FIGURE 14.1. The structure of ties among leaders in Chicago, 2002

To do this, I first generated a respondent-by-respondent matrix for each community area in which the entries in off-diagonal cells register the number of times respondent i and respondent j cited the same key contact. Density is calculated as the sum of these off-diagonal cells divided by the total possible common cites.13 Three features of this connectivity measure are worthy of note. First, all leader respondents are included—those who failed to make a single citation are not excluded. This course is taken because the fact of not making a citation is meaningful structurally; the respondent is an isolate. On the assumption that the sampling procedure produces a comparable “stain” of networks in different communities, the tendency to pick up peripheral actors will then reflect real differences in the cohesion of these neighborhoods. Second, instead of normalizing by the total possible number of citations, one could normalize based on the actual citations made. This, however, would also mean a loss of information because the fact that someone did not make the full five nominations is meaningful. Across neighborhoods, the tendency to make fewer nominations is an important conceptual component of what we mean by “density.”

Third, an important insight of network analysis is that cohesion may not simply be a matter of direct ties. Rather, chains of indirect ties may bridge actors, getting closer to the idea that Granovetter originally raised about the West End. The density measure is based on a “path-distance” matrix—the tendency of Chicago’s leaders to cite common alters, a two-step tie. Some of these ties can be in the community and others not. If an alderman in Lakeview is connected to a business leader in the Loop that a Lakeview minister is also connected to, for example, they share an indirect tie. The more ties that are overlapping, the more we can say that, in a connectivity sense, the community leadership structure is cohesive. Looking even further at path distances allows us to get a sense of the larger structure of relations in a network. That is, while one- or two-step connections may indicate a relatively sparse network, a look at three-step or four-step or higher-step ties might show that the structure is ultimately quite dense. To the extent that a structure does not appear denser when multisteps are considered, that network is composed of isolated cliques. To capture this idea a higher-order path-distance matrix was generated by taking the density matrix to successive powers, allowing construction of indirect density.14 A revealing finding is that densely connected communities tend also to be characterized by chains of higher-order indirect ties, suggesting that they are tapping the same phenomenon. For example, the multistep measure correlated with the two-step density measure at 0.87 (p < 0.01), and Hyde Park came out on top in both. I thus focus in this chapter primarily on the simpler indicator of two-step ties.

A related network measure that I examine captures more directly the centralization or “agreement” in how key informant ties extend to individual alters. Here the focus is more on the distribution among the cited alters (where the action is going) than on the nominators. At one end of the spectrum we can imagine the unusual situation of a community in which all leaders go to the same and only alter (again, inside or outside the community), which would indicate perfect agreement and overlap. At the other end we might imagine a situation in which leaders are isolated and each nominates a unique individual. To capture these variations, I examine the tendency for a few alters to receive most of the nominating action. For the overall index of centralization, I count all alters, those within the community of interest or outside it, although the nominations can only come from respondents within a given community.15 The index is based on the Herfindahl formula, a widely used measure of concentration, which in the present case is equal to the sum of the squares of each alter’s share of nominations coming from a given community. The centralization index captures the extent to which nominations go to a smaller rather than larger numbers of alters, as well as the variation in the degree of inequality in the number of citations received by all alters nominated by respondents in a community.16

A more modern rendering of the ideas that Granovetter raised about Boston’s West End is the distinction between what Robert Putnam calls “bonding” ties (strong ties within communities) and “bridging” ties (weak ties among communities).17 The density and centralization measures capture a bit of both, depending on where alters are located. Alters outside or external to the community are by definition bridging ties at the community level. Another strategy is to measure the indegree and outdegree of each community similar to the residential migration analysis of the last chapter. A community that receives leadership nominations from more distinct communities (indegree) is in a real sense more central to the structure of interlocking ties. A community that sends ties to more distinct communities (outdegree) is also connected externally but in a very different way.

Another and perhaps more satisfying indicator of bridging ties at the macro level is the extent to which a community serves as a connector or mediator of ties in the citywide structure. For the sampled network of forty-seven communities in 1995 and again in the thirty communities in 2002, I examined the extent to which leaders were connected to pairs of alters who are not directly connected to each other, putting them in a position to control information and resource flows between leaders with no direct ties. I then extended this concept to the contextual level to derive the number of shortest paths between pairs of communities that were generated by Chicago’s leaders and that were mediated by a given community. We can think of this type of connection as the brokerage or mediation of intercommunity ties—specifically, the measure taps the extent to which any given community serves as a hub through which leadership connections are flowing, commonly known as “centrality.”18

Results

The church cannot be an island.

Author interview with the pastor of a leading church on the South Side of

Chicago, April 5, 2007

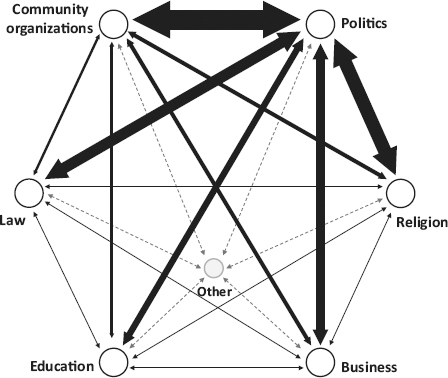

Figure 14.2 recasts the individual connections in figure 14.1 to show how institutional domains in Chicago are interrelated. Recall that six institutional domains were sampled, and a seventh “other” was derived from the snowball sampling. Leaders of community organizations and educational institutions represented about a quarter of all respondents. Leaders in law enforcement, religion, and business represented between about 12 and 17 percent of respondents. By far the smallest domain in absolute number came from politics, representing just 6 percent of the sample. This makes sense, as there are not that many political actors to go around—this domain was quickly “saturated” such that it can be thought of not as a sample from communities but the full population.19

It may come as something of a surprise, then, to see how the action among leaders in Chicago is manifested in terms of interdomain connections. Although small in original numbers, the institutional domain of politics looms large in terms of interdomain connectivity and the frequency with which leaders of all organizational affiliations turn to politicians. Indeed, we see in figure 14.2 that of all the domains, politics is the most embedded institutionally. The arrows are proportional to the volume of interinstitutional connections, with politics disproportionately linked across the board. It is perhaps expected that community organizations and politicians are deeply tied, and they are, but politics is nearly as intertwined with religious institutions. The influential pastor quoted above was expressing an apparent reality of how much religion is interconnected with the practical workings of everyday life, which go well beyond matters of faith. The church he led was deeply enmeshed not just with politics and politicians but community organizations, business leaders, educational reformers, and local economic development. Community organizations, which might be thought to be more widely connected, are relatively weakly tied (perhaps unfortunately) to key leaders in education and law. The “other” category is weakly tied to all dimensions, although clearly each kind of institutional domain is connected to this more nontraditional community actor.

FIGURE 14.2. Interinstitutional connections

In short, figure 14.2 reveals a number of connections that are not part of typical organizational charts. Religious leaders do not do only religion—one of their biggest influences concern politics. Education leaders are not just about education, and the influential leaders in community organizations have relatively more ties to business than they do to education or law enforcement. Isolated institutional domains would appear to be at a significant disadvantage in the same way that isolated individual leaders are.

Community and Temporal Context

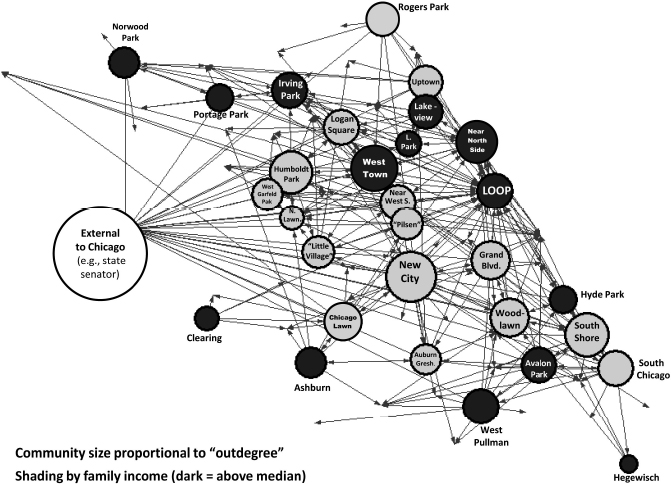

A major goal of this chapter is to explore intercommunity ties, and so I focus for the remainder of analysis on the multiple ways that communities are differentially tied together or isolated as a result of the concrete ties among individual leaders. One of the most helpful strategies is to view the nature of ties at Granovetter’s “aerial level,” which I present in figure 14.3.20 Here we see the emergent consequences of individual leader ties for the community social structure of Chicago. Nodes are the sampled community areas, and arrows reflect ties. The size of the nodes is in proportion to outdegree, or the number of distinct communities to which a community sends ties. Only sampled communities can be senders, and so I graph the full network of senders (N = 30 communities). Any community area in Chicago can and does receive ties, as noted by the arrows, but for parsimony the circles and labels are limited to the representative set of sending communities, with the major exception on the left of a non-Chicago type of receiver—the governor, state senators, and other “external” actors who are outside the original sample but nonetheless of considerable substantive interest. Because of the central role that economic status plays in most discussions of social networks and community power, I also classify these communities according to whether they are above or below the median in family income as of 2000.

The results show that certain areas of the city are hubs of activity in terms of connectivity, most noticeably the Loop and Near North Side. But there are regional nodes that are actively connected too on the South Side and Near West Side. There is also a considerable degree of connectivity in the overall citywide network—few communities are islands, although communities do vary in their degree of isolation. It is important to note that while not a large association, income is negatively related to outdegree when further standardized by the number of respondents in each sending community (correlation = –0.22). A number of poorer communities thus seem to stand out in terms of its leaders actively reaching outside and making contacts with leaders in many different communities around the city. While this finding goes against a prominent belief that poor communities are isolated in terms of connections to the outside world or the “mainstream,” it makes sense to the extent that communities are resource dependent and need to establish external linkages to perceived movers and shakers.

FIGURE 14.3. Community-level structure of influence ties: outdegree of sending communities by income status

The natural question that arises is how cohesive these patterns are by community. It might be, for example, that a community is resource dependent and its leaders reach out and send a lot of ties to other communities but with virtually no agreement or connections among themselves. Likewise, a community can send a lot of ties but not broker or mediate ties from other communities, another sign of dependence rather than active intervention in the city’s web of connections. The data suggest that the density of leadership contacts and the concentration of alter nominations are tapping a similar dimension of cohesive leadership structure, correlating significantly and substantially at 0.73 (p < 0.01) in 2002. “Betweenness,” which I have defined as a kind of community brokerage indicator, is uncorrelated with the outdegree measure graphed in figure 14.3 and significantly negatively correlated with the centralization of nominations within a community (–0.41) despite the relatively small number of cases. Therefore we find two distinct dimensions, one a cohesive internal leadership structure and the other a mediating role in which a given community serves as a junction that ties together otherwise disconnected communities. The Loop, for example, has a high number of external contacts relative to its size and a high number of connections that mediate between other communities but at the same time its leaders are not terribly coherent internally in their mutual or overlapping contacts.

Another key finding concerns temporal stability. The KeyNet study was designed to measure turnover among leadership positions, and in fact turnover was fairly intense, with some 60 percent of respondents in 2002 new to the position relative to 1995. This raises a simple but consequential question: If there is individual turnover, how stable is the overall structure of contacts? It is not inevitable that the churning of individual leaders means fundamental change in the pattern of relations. As I have shown throughout the book, there is often a durability of inequality, social climate, and organizational life, all while the social structure is dynamic. In chapter 8, for example, I showed a high degree of relative stability in the density of nonprofit organizations extending well over a decade. Similarly, there is lots of residential mobility by individuals but a strong inertial quality to neighborhood inequality. This means that any individual leader new to a position is stepping into an ongoing history and structure of relations going well beyond his or her particular background, organizational affiliation, or community.

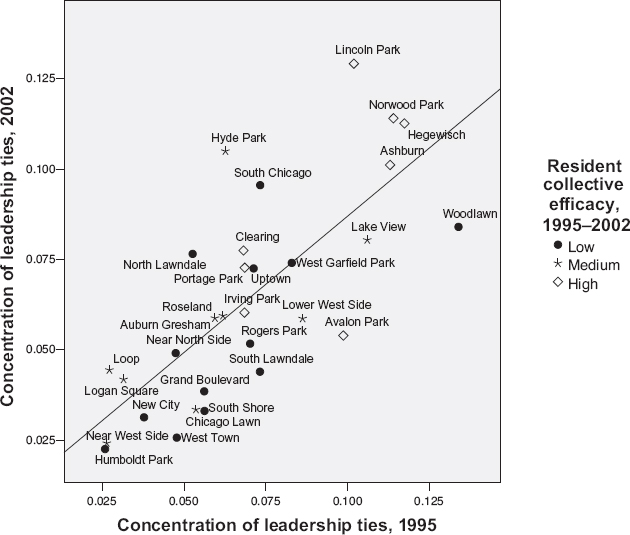

I directly examine this hypothesis in figure 14.4 by displaying the concentration or cohesiveness of leadership influence by community across time. I also denote each community by whether it is low, medium, or high in resident-level collective efficacy. Two patterns are clearly evident. First, network properties of social organization among elites are quite stable over time (1995–2002) despite considerable turnover in the individuals who occupy the positions. Communities that tend to have a high density of overlap in the contact networks of their leaders— whether internal or external to the community—remain densely interconnected even as the individual leaders are replaced. The centrality measure also correlates positively over time (0.54, p < .01). Analogous to residential migration, despite considerable change at the individual level, the underlying structure of relations across communities is remarkably persistent.

FIGURE 14.4. Persistence of network cohesiveness despite leadership turnover

Second, figure 14.4 shows that those communities that sit at the upper end of a stable cohesive leadership structure also tend to be high in collective efficacy. A partial exception is Woodlawn, which is low in collective efficacy but saw a significant drop in its relative leadership cohesion over the period. South Chicago is another exception, similarly low in collective efficacy but seeing an increase in its leadership connectivity. Hyde Park and Lincoln Park are medium to high in collective efficacy and saw unexpected increases to the point that they are among the highest in the city in 2002 leadership concentration. Overall, though, communities characterized by fragmentary leadership or low concentration of tie nominations, such as the Near West Side, Grand Boulevard, and New City, are low in collective efficacy, and several, consistent with the story of the West End told by Gans, have seen radical interventions by the city in the form of new urban renewal (or displacement) that they were unable to stop.

It is instructive to recall again the network structure of the communities introduced in chapter 1, Hegewisch and South Shore (fig. 1.4). These two communities stand at the opposite poles of leadership centralization, further illustrating the range of variation in the density of internal network structures across Chicago communities. The leadership network structure of South Shore is characterized by more external contacts and a larger number of isolated key informants than Hegewisch. Moreover, the few respondents who are tied to others tend to form isolated cliques rather than a dense, well-connected network as in Hegewisch. Interestingly, South Shore is disadvantaged on a number of social dimensions compared to Hegewisch, even though both are not high-income communities. South Shore has a low-birth-weight score that is a full one standard deviation above the citywide average, for example, whereas Hegewisch has a low-birth-weight score that is one standard deviation below the average. This pattern suggests that wellbeing is connected to leader networks.

Taking the larger bird’s-eye view suggests an even more general pattern. Where leadership connections are concentrated or less fragmented, we find better health and lower violence across the city. The correlation of the network concentration scores in 2002 with infant mortality rates, percentage of births to teenagers, and homicide rates in 2002–6 is –0.406, –0.309, and –0.527, respectively, across Chicago communities. A concern is that these correlations may be artifically induced by the compositional characteristics of these same communities. But as we saw earlier, economic status is weakly related to leadership network structure. More important, the centralization of leadership ties is a significant predictor of lower homicide and teen birth rates in future years after controlling for the potentially confounding factors of concentrated disadvantage, residential stability, organizational density, and the number of communities to which a focal community is tied (outdegree).21 Thus the level of connectivity of leadership ties in a community is directly related to core outcomes of this book, especially wellbeing in the form of lower violence.

Composition or Social Processes?

The question remains as to what kinds of community characteristics produce variations in leadership connectivity. Is collective efficacy spuriously associated with the density of elite ties in a community? What about concentrated disadvantage and racial composition? And what about the internal versus external nature of community ties? The data tell a simple but powerful story. Namely, the sociodemographic and poverty composition of communities does not determine the kinds of leadership configurations I have charted thus far. Concentrated disadvantage in particular is rather weakly connected to the cohesiveness of leadership and is only modestly predictive of the centrality of a community’s position in mediating elite ties. Residential stability, median income, and percent black are weakly correlated as well. But, as we have seen, the cohesiveness and shared expectations of residents is linked to the nature of leadership ties. Because leaders are in a fundamental sense dependent on the residents and organizations they serve, it follows that communities with high shared expectations for social control among their residents would expect or at least help shape a more integrated rather than fragmented leadership style, regardless of the compositional makeup of the community.

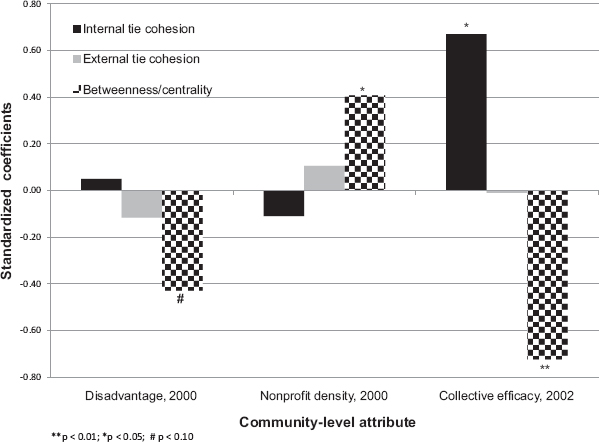

I assess these relationships as a whole by examining simultaneous influences. Because of the small number of cases, however, my statistical power is limited. So I examine a parsimonious model that examines those factors highlighted in previous chapters and specified by the theoretical framework I have built up—sociodemographic composition, organizational density, and collective efficacy (see especially chapters 7 and 8). In separate analysis I examined a series of alternative models (e.g., with income and racial composition as controls), but the basic findings were similar. My outcomes of interest are the centrality of communities in mediating leadership contacts and the concentration or density of agreement within communities. To get at the idea of internal versus external ties, I disaggregate the concentration measure into two indices. One taps the concentration or agreement among leaders about alters in the same community. The second restricts the concentration (or Herfindahl index) to shared elite ties outside the community. In other words, I ask the question: Do the leaders of a particular community agree or cohere around a set of “go-to” contacts even if those contacts are externally located? I then examine variations in this purely external kind of tie.

The results in figure 14.5 show that disadvantage is modestly connected to lower centrality but not the concentration of leadership ties. Both residential stability and a community’s outdegree were insignificant across all three outcomes. For the sake of parsimony, these two factors are thus controlled but not shown in the figure. Once disadvantage, residential stability, and the number of sending communities are taken into account, we see that collective efficacy is significantly and positively related to a more cohesive leadership structure but only among those alters who share the same community. Moreover, collective efficacy is negatively related to centrality and unrelated to the external concentration of alter nominations.

The picture seems to be that cohesive communities defined by resident collective efficacy and internally shared alter-elites are not the same ones serving as the largest hubs of intercommunity activity, even though they are not particularly isolated in this regard. What seems to matter most for explaining the centrality of a community in mediating intercommunity ties is the density of its nonprofit organizations, an internal attribute. In further analysis I replicated this finding with the centralization of elite ties in 1995 and the density of organizations in 1994 as the predictor, along with 1990 census data and 1995 outdegree. Consistent with but building on the findings of chapter 8, then, where there is greater organizational density we see more “outreach” and a higher degree of centrality of the community in its city-wide pattern of leadership ties. Organizational effects apparently reverberate within and beyond the borders of any given community.

The bottom line is that community social processes—collective efficacy and organizational density—and not demography or income are doing the major work in fostering connective network structures. This finding reinforces a central claim of the book and also the argument in this section that local and extralocal factors are not necessarily in competition but are mutually contributing to the social organization of the city. More generally, much of the impetus for social network research seems to be in pursuit of the idea that only relational connections matter (i.e., the “structure”) as opposed to the social or cultural attributes of the lower-order units—in this case, communities. I believe this impetus is mistaken—the present theoretical framework argues that both kinds of factors are simultaneously at work and are associated in systematic and mutually reinforcing ways.

FIGURE 14.5. Community sources of variability in three types of leadership connectivity. (Internal cohesion, R2 = 0.34, p < 0.10; External cohesion R2 = 0.13, n.s; Betweenness centrality R2 = 0.48, p < 0.01.)

Linking Migrations Flows and Elite Connections

In an age of modern communication and asserted placelessness, a dominant view is that elite networks are weakly constrained by the local environment and unlikely to be enabled by mere spatial proximity. Communication, especially among elites, is not seen as limited by geography. Even less attention is typically paid to how the attributes of network actors may play an important role in understanding relational properties of the network dynamics.

To address this gap, I examined the pairwise ties among a representative set of Chicago communities in a manner directly analogous to chapter 13, but here with the tie defined by leadership contact. In addition to the characteristics considered in chapter 13 (see fig. 13.3), I examine pairwise ties previously formed by migration from 1995 to 2002. In other words, the outcome now is the volume of key informant network ties between pairs of communities in 2002 as a function of spatial distance, structural distance, social climate difference, and residential migration pathways up to that point in time.

The results suggest that once again the placelessness critique does not describe how people act, in this case among elites with enhanced options. The effect of spatial distance is highly significant (p < .01) as it was for residential mobility and second largest in magnitude, attenuating intercommunity connections. The standard structural characteristics, such as income and racial composition, do not explain patterns of intercommunity leadership ties once spatial distance is accounted for. Neither does similarity in collectively perceived disorder or friendship ties explain key-informant ties between different communities unlike they did for migration ties. Most important, there is a clear and substantial finding that speaks to the importance of intercommunity dynamic flows. Communities that experienced a higher volume of residential exchange in the late 1990s and into 2000 are much more likely to have increased connections among their leaders, controlling for demographic similarities and other social factors. In fact, after alternative explanations are taken into account, the magnitude of the estimated effect of migration networks is larger than all others (p < 0.01). It appears that migration flows are tapping the exchanges of people between communities that are productive of informational channels and ultimately elite influence ties. Moreover, similarity in the level of organizational participation generates intercommunity ties as well (p < .05). Although smaller in magnitude than spatial proximity or migration ties, the organizational link makes sense based on the findings and theoretical expectations set by chapter 8 and chapter 13.

The mechanism of residential sorting identified in chapter 13 thus appears to be general in nature, reaching all the way to between-community elite variations in influence ties. Although unobserved on an everyday basis, I posit that there is an undercurrent of social interactions connecting communities, residents, and leaders alike across the city, producing a structure that is not immediately apparent or visible from inside a single community.

Conclusion

This chapter has only scratched the surface of the nature of elite connections in Chicago. There are a number of questions to be pursued further and a rich set of analyses that can be imagined.22 But my present concern is theoretically focused on how leadership ties connect to the broader arguments of this book. I thus pursued a limited set of analyses that followed logically and theoretically from the previous chapters. I believe the results tell a clear story.

First and foremost, the structure of elite network ties varies considerably across communities, as previewed in chapter 1 (fig. 1.4). Networks can in theory go anywhere, but they go to a somewhere very regularly—there is little that is random or nonstructured about the networks we have observed. Second, network properties of social organization among elites are highly persistent over time (1995–2002), despite considerable turnover of the individuals who occupy the positions. For example, communities that tend to have a high density of overlap in the contact networks of their leaders remain this way even as the individual leaders are frequently replaced. Analogous to migration, the underlying structure is enduring despite considerable change, lending a further layer of empirical support to the conceptual framework of this book. Awareness of this pattern was also uncovered in my personal interviews with a set of leaders from different domains, including the pastor quoted earlier, the vice president of a major university charged with community affairs, a housing development executive, a law enforcement official involved with crime prevention, and the president of a major philanthropic foundation, among others. The cognitive perception of the stability of key leadership structures over time suggests that reciprocity norms un-dergird much of the elite influence structure in Chicago.

A third finding is that the variability in leadership network structure by community is not determined solely or even in large measure by the demographic and economic makeup of the community. This is an important point and one not anticipated by standard accounts. Instead of the usual urban suspects, social properties like collective efficacy and organizational density independently predict network structure. Moreover, these vary depending on whether the ties are local or extralocal in nature. Granovetter was right in his intuition that the aerial view produces a different picture, but what is also clear is that the internal view is not irrelevant either—including the kinds of factors that Gans highlighted. Both internal factors, like collective efficacy and a community’s organizational infrastructure, bear on the network structures that link communities.

Fourth, there is evidence that the social nature of leadership network structures has independent explanatory power in our understanding of the wellbeing of communities. Controlling for key sociodemographic factors, for example, cohesive leadership structures are directly related to lower rates of violence and teenage births. Because wellbeing along these dimensions is not simply about residents but organizations and leaders, this result is a hopeful signal that, when combined with results of earlier chapters, suggests possible points of intervention. I take this point up in the concluding chapter.

Finally, and perhaps most important for this section of the book, I have shown that migration flows among communities are directly related to the network flows defined by leadership ties. These are radically different behaviors or choices—residents deciding where to move and elites making a connection with other elites. The link between the two is not explained by demography or economic status and thus supports the thesis of a structural sorting that simultaneously takes into account individual actions and social composition. Taken together, the chapters in this section strongly suggest that the higher-order structure of Chicago—or its interdependent social fabric—has an underlying “neighborhood network” logic.