Chapter 3 Character

When I find a well-drawn character in fiction or biography, I generally take a warm personal interest in him, for the reason that I have known him before — met him on the river.

Character is essential to plot. Without characters, Grace Paley’s “Wants” would be a list of the cost of overdue library books and Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily” little more than a faded history of a sleepy town in the South. If stories were depopulated, the plots would disappear because characters and plots are interrelated. A library fee is important only because we care what effect it has on a character. Characters are influenced by events just as events are shaped by characters. The protagonist of Paley’s story is someone who is intellectually curious and often unwilling to conform to society’s guidelines: the facts that she has kept library books for a very long time and that she returns them and cheerfully pays what she owes, comprise the basic plot of “Wants,” but they are also strong indications of the type of person she is.

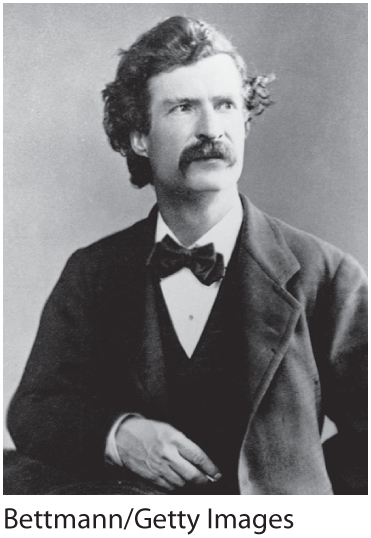

The methods by which a writer creates people in a story so that they seem actually to exist are called characterization. Huck Finn never lived, yet those who have read Mark Twain’s novel about Huck’s adventures along the Mississippi River feel as if they know him. A good writer gives us the illusion that a character is real, but we should also remember that a character is not an actual person but instead has been created by the author. Though we might walk out of a room in which Huck Finn’s Pap talks racist nonsense, we would not throw away the book in a similar fit of anger. This illusion of reality is the magic that allows us to move beyond the circumstances of our own lives into a writer’s fictional world, where we can encounter everyone from royalty to paupers, murderers, lovers, cheaters, martyrs, artists, destroyers, and, nearly always, some part of ourselves. The life that a writer breathes into a character adds to our own experiences and enlarges our view of the world.

A character is usually but not always a person. In Jack London’s Call of the Wild, the protagonist is a devoted sled dog; in Ernest Hemingway’s “The Short, Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” the story’s point of view occasionally enters the mind of a wounded lion. Perhaps the only possible qualification to be placed on character is that whatever it is — whether an animal or even an inanimate object, such as a robot — it must have some recognizable human qualities. The action of the plot interests us primarily because we care about what happens to people and what they do. We may identify with a character’s desires and aspirations, or we may be disgusted by his or her viciousness and selfishness. To understand our response to a story, we should be able to recognize the methods of characterization the author uses.