The pleasure of words

The impulse to create and appreciate poetry is as basic to human experience as language itself. Although no one can point to the precise origins of poetry, it is one of the most ancient of the arts, because it has existed ever since human beings discovered pleasure in language. The tribal ceremonies of peoples without written languages suggest that the earliest primitive cultures incorporated rhythmic patterns of words into their rituals. These chants, very likely accompanied by the music of a simple beat and the dance of a measured step, expressed what people regarded as significant and memorable in their lives. They echoed the concerns of the chanters and the listeners by chronicling acts of bravery, fearsome foes, natural disasters, mysterious events, births, deaths, and whatever else brought people pain or pleasure, bewilderment or revelation. Later cultures, such as the ancient Greeks, made poetry an integral part of religion.

Thus, from its very beginnings, poetry has been associated with what has mattered most to people. These concerns — whether natural or supernatural — can, of course, be expressed without vivid images, rhythmic patterns, and pleasing sounds, but human beings have always sensed a magic in words that goes beyond rational, logical understanding. Poetry is not simply a method of communication; it is a unique experience in itself.

What is special about poetry? What makes it valuable? Why should we read it? How is reading it different from reading prose? To begin with, poetry pervades our world in a variety of forms, ranging from advertising jingles to song lyrics. These may seem to be a long way from the chants heard around a primitive campfire, but they serve some of the same purposes. Like poems printed in a magazine or book, primitive chants, catchy jingles, and popular songs attempt to stir the imagination through the carefully measured use of words.

Although reading poetry usually makes more demands than does the kind of reading we use to skim a magazine or newspaper, the appreciation of poetry comes naturally enough to anyone who enjoys playing with words. Play is an important element of poetry. Consider, for example, how the following words appeal to the children who gleefully chant them in playgrounds:

I scream, you scream

We all scream

For ice cream.

These lines are an exuberant evocation of the joy of ice cream. Indeed, chanting the words turns out to be as pleasurable as eating ice cream. In poetry, the expression of the idea is as important as the idea expressed.

But is “I scream…” poetry? Some poets and literary critics would say that it certainly is one kind of poem because the children who chant it experience some of the pleasures of poetry in its measured beat and repeated sounds. However, other poets and critics would define poetry more narrowly and insist, for a variety of reasons, that this isn’t true poetry but merely doggerel, a term used for lines whose subject matter is trite and whose rhythm and sounds are monotonously heavy-handed.

Although probably no one would argue that “I scream…” is a great poem, it does contain some poetic elements that appeal, at the very least, to children. Does that make it poetry? The answer depends on one’s definition, but poetry has a way of breaking loose from definitions. Because there are nearly as many definitions of poetry as there are poets, Edwin Arlington Robinson’s succinct observations are useful: “[P]oetry has two outstanding characteristics. One is that it is undefinable. The other is that it is eventually unmistakable.”

This comment places more emphasis on how a poem affects a reader than on how a poem is defined. By characterizing poetry as “undefinable,” Robinson acknowledges that it can include many different purposes, subjects, emotions, styles, and forms. What effect does the following poem have on you?

I am 25 1955

With a love a madness for Shelley

Chatterton Rimbaud

and the needy-yap of my youth

has gone from ear to ear:

I HATE OLD POETMEN!

Especially old poetmen who retract

who consult other old poetmen

who speak their youth in whispers,

saying:—I did those then

but that was then

that was then—

O I would quiet old men

say to them:—I am your friend

what you once were, thru me

you’ll be again—

then at night in the confidence of their homes

rip out their apology-tongues

and steal their poems.

All of this careful unpacking is what the poem demands. You could accurately say, “Gregory Corso’s ‘I am 25’ is about a young poet who struggles to assert his voice in a world dominated by old poets.” As you can see, reading a description of what happens in a poem is not the same as experiencing a poem. The exuberance of “I scream (for ice cream)” and the somewhat sinister promise of violence in “I am 25” are in the hearing or reading rather than in the retelling. A paraphrase is a prose restatement of the central ideas of a poem in your own language. Consider the difference between the following poem and the paraphrase that follows it. What is missing from the paraphrase?

Catch 1950

Two boys uncoached are tossing a poem together,

Overhand, underhand, backhand, sleight of hand, every hand,

Teasing with attitudes, latitudes, interludes, altitudes,

High, make him fly off the ground for it, low, make him stoop,

Make him scoop it up, make him as-almost-as-possible miss it,

Fast, let him sting from it, now, now fool him slowly,

Anything, everything tricky, risky, nonchalant,

Anything under the sun to outwit the prosy,

Over the tree and the long sweet cadence down,

Over his head, make him scramble to pick up the meaning,

And now, like a posy, a pretty one plump in his hands.

Paraphrase: A poet’s relationship to a reader is similar to a game of catch. The poem, like a ball, should be pitched in a variety of ways to challenge and create interest. Boredom and predictability must be avoided if the game is to be engaging and satisfying.

A paraphrase can help us achieve a clearer understanding of a poem, but, unlike a poem, it misses all the sport and fun. It is the poem that “outwit[s] the prosy” because the poem serves as an example of what it suggests poetry should be. Moreover, the two players — the poet and the reader — are “uncoached.” They know how the game is played, but their expectations do not preclude spontaneity and creativity or their ability to surprise and be surprised. The solid pleasure of the workout — of reading poetry — is the satisfaction derived from exercising your imagination and intellect.

That pleasure is worth emphasizing. Poetry uses language to move and delight even when it threatens to rip out the tongues of old men. The pleasure is in having the poem work its spell on us. For that to happen, it is best to relax and enjoy poetry rather than worry about definitions of it. Pay attention to what the poet throws you. We read poems for emotional and intellectual discovery — to feel and to experience something about the world and ourselves. The ideas in poetry — what can be paraphrased in prose — are important, but the real value of a poem consists in the words that work their magic by allowing us to feel, see, and be more than we were before. Perhaps the best way to approach a poem is similar to what Francis’s “Catch” implies: expect to be surprised, stay on your toes, and concentrate on the delivery.

A sample student analysis

Tossing Metaphors Together in Robert Francis’s “Catch”

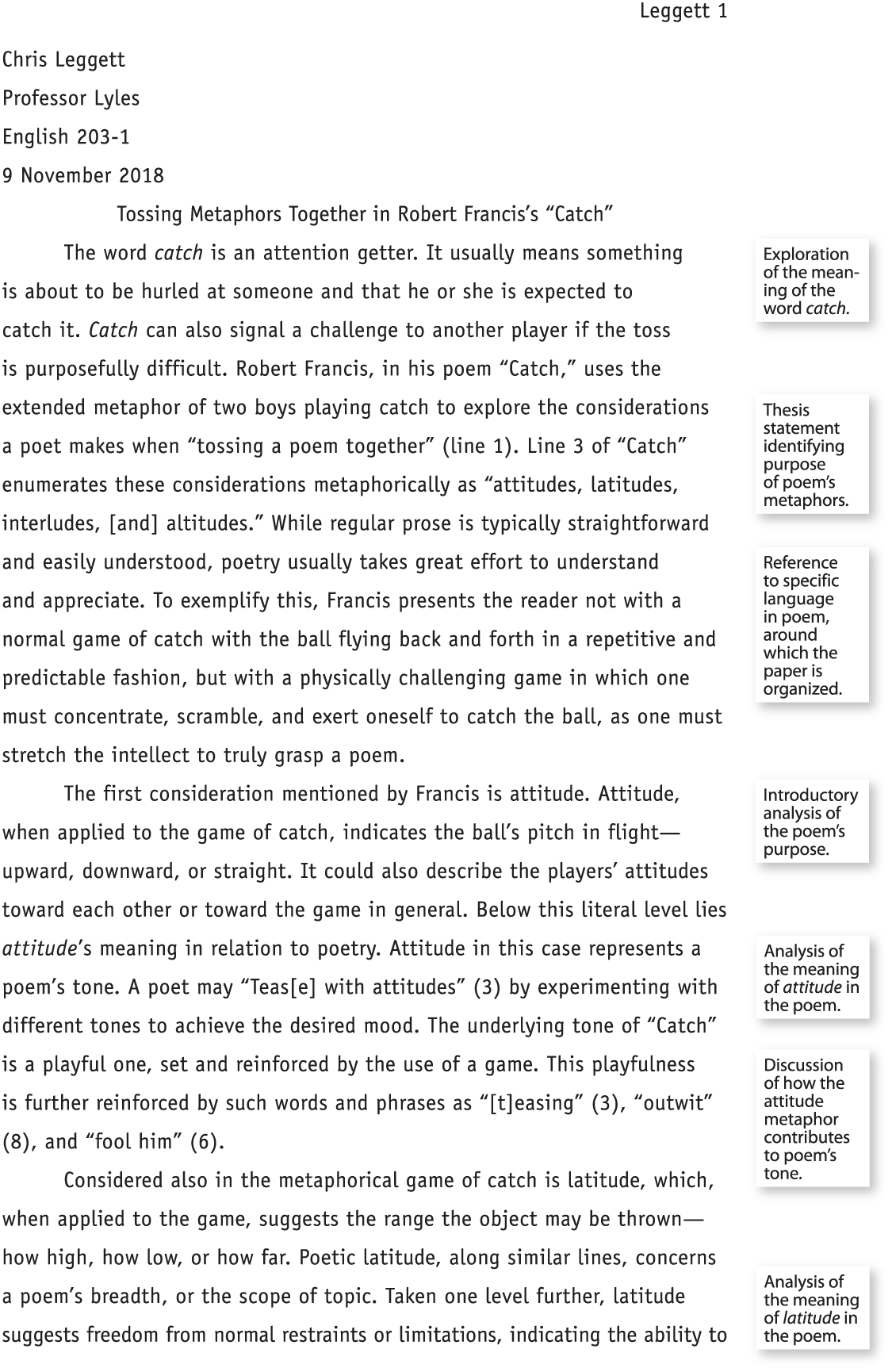

The following sample paper on Robert Francis’s “Catch” was written in response to an assignment that asked students to discuss the use of metaphor in the poem. Notice that Chris Leggett’s paper is clearly focused and well organized. His discussion of the use of metaphor in the poem stays on track from beginning to end without any detours concerning unrelated topics (for a definition of metaphor). His title draws on the central metaphor of the poem, and he organizes the paper around four key words used in the poem: “attitudes, latitudes, interludes, altitudes.” These constitute the heart of the paper’s four substantive paragraphs, and they are effectively framed by introductory and concluding paragraphs. Moreover, the transitions between paragraphs clearly indicate that the author was not merely tossing a paper together.

Text on the top left portion of the page reads,

Chris Leggett

Professor Lyles

English 2 0 3 dash 1

9 November 2018

Tossing Metaphors Together in Robert Francis’s open quotes Catch close quotes.

Paragraph 1. The word catch is an attention getter. It usually means something is about to be hurled at someone and that he or she is expected to catch it. Catch can also signal a challenge to another player if the toss is purposefully difficult. Robert Francis, in his poem open quotes Catch, close quotes uses the extended metaphor of two boys playing catch to explore the considerations a poet makes when open quotes tossing a poem together close quotes. [A corresponding margin note reads, Exploration of the meaning of the word catch]. Line 3 of open quotes Catch close quotes enumerates these considerations metaphorically as open quotes attitudes, latitudes, interludes, [and] altitudes close quotes. While regular prose is typically straightforward and easily understood, poetry usually takes great effort to understand and appreciate. [A margin note reads, Thesis statement identifying purpose of poem’s metaphors.] To exemplify this, Francis presents the reader not with a normal game of catch with the ball flying back and forth in a repetitive and predictable fashion, but with a physically challenging game in which one must concentrate, scramble, and exert oneself to catch the ball, as one must stretch the intellect to truly grasp a poem. [A corresponding margin note reads, Reference to specific language in poem, around which the paper is organized].

Paragraph 2. The first consideration mentioned by Francis is attitude. Attitude, when applied to the game of catch, indicates the ball’s pitch in flight (hyphen) upward, downward, or straight. It could also describe the players’ attitudes toward each other or toward the game in general. Below this literal level lies attitude’s meaning in relation to poetry. [A margin note reads, Introductory analysis of the poem’s purpose.]

Attitude in this case represents a poem’s tone. A poet may open quotes Teas[e] with attitudes close quotes (3) by experimenting with different tones to achieve the desired mood. [A corresponding margin note reads, Analysis of the meaning of attitude in the poem.] The underlying tone of open quotes Catch close quotes is a playful one, set and reinforced by the use of a game. This playfulness is further reinforced by such words and phrases as open quotes [t]easing close quotes (3), open quotes outwit close quotes (8), and open quotes fool him close quotes (6). [A corresponding margin note reads, Discussion of how the attitude metaphor contributes to poem’s tone.]

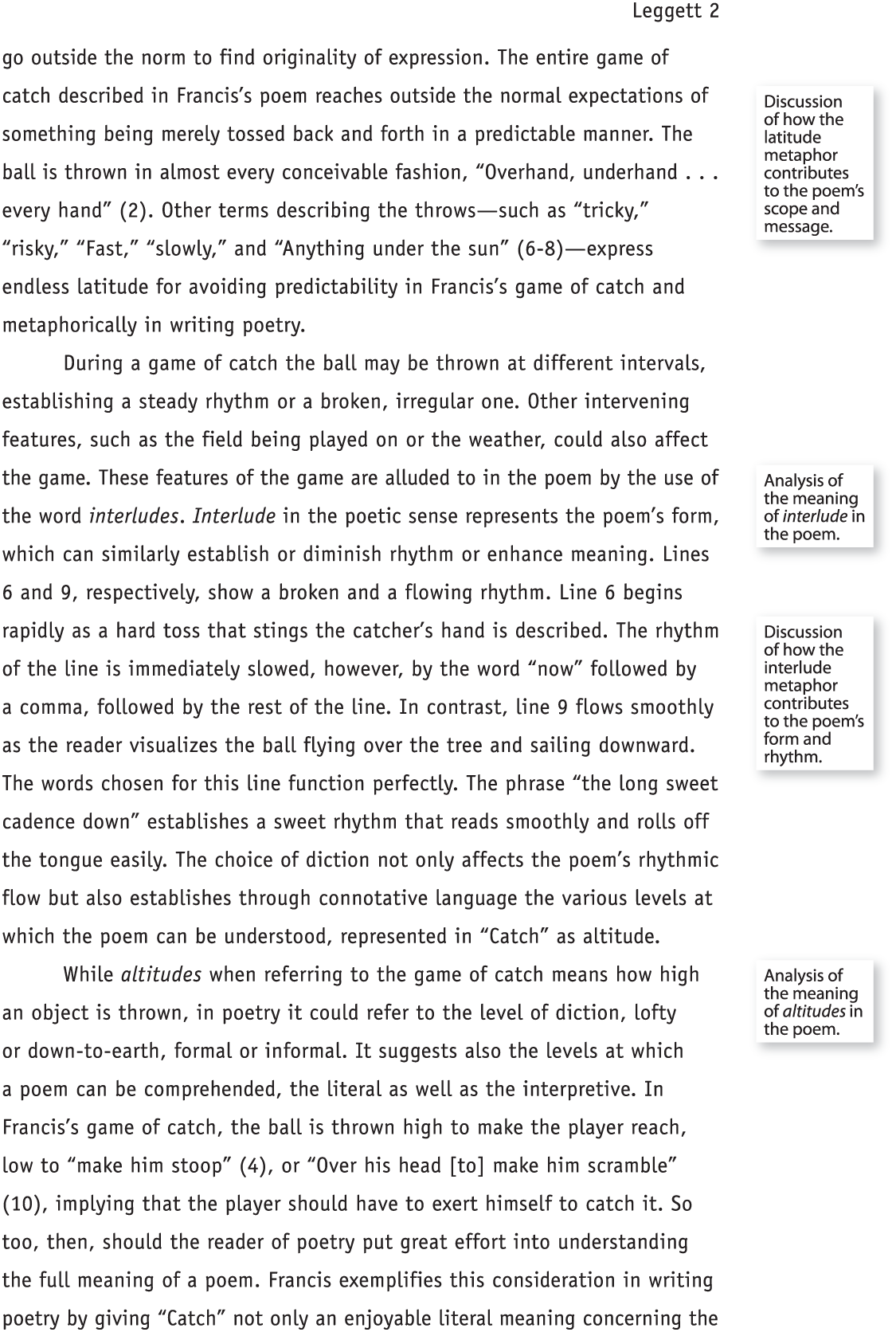

Paragraph 3. Considered also in the metaphorical game of catch is latitude, which, when applied to the game, suggests the range the object may be thrown (hyphen) how high, how low, or how far. Poetic latitude, along similar lines, concerns a poem’s breadth, or the scope of topic. Taken one level further, latitude suggests freedom from normal restraints or limitations, indicating the ability to (ellipsis) [A corresponding margin note reads, Analysis of the meaning of latitude in the poem.]

Text continues as follows:

(Ellipsis) go outside the norm to find originality of expression. The entire game of catch described in Francis’s poem reaches outside the normal expectations of something being merely tossed back and forth in a predictable manner. The ball is thrown in almost every conceivable fashion, open quotes Overhand, underhand (ellipsis) every hand close quotes (2). Other terms describing the throws(hyphen) such as open quotes tricky, close quotes open quotes risky, close quotes open quotes Fast, close quotes open quotes slowly, close quotes and open quotes Anything under the sun close quotes (6-8)(hyphen) express endless latitude for avoiding predictability in Francis’s game of catch and metaphorically in writing poetry. [A corresponding margin note reads, Discussion of how the latitude metaphor contributes to the poem’s scope and message.]

Paragraph 4. During a game of catch the ball may be thrown at different intervals, establishing a steady rhythm or a broken, irregular one. Other intervening features, such as the field being played on or the weather, could also affect the game. These features of the game are alluded to in the poem by the use of the word interludes. [The word ‘interlude’ is italicised and a corresponding margin note reads, Analysis of the meaning of interlude in the poem.] Interlude in the poetic sense represents the poem’s form, which can similarly establish or diminish rhythm or enhance meaning. Lines 6 and 9, respectively, show a broken and a flowing rhythm. Line 6 begins rapidly as a hard toss that stings the catcher’s hand is described. The rhythm of the line is immediately slowed, however, by the word open quotes now close quotes followed by a comma, followed by the rest of the line. In contrast, line 9 flows smoothly as the reader visualizes the ball flying over the tree and sailing downward. The words chosen for this line function perfectly. The phrase open quotes the long sweet cadence down close quotes establishes a sweet rhythm that reads smoothly and rolls off the tongue easily. The choice of diction not only affects the poem’s rhythmic flow but also establishes through connotative language the various levels at which the poem can be understood, represented in open quotes Catch close quotes as altitude.

[A corresponding margin note reads, Discussion of how the interlude metaphor contributes to the poem’s form and rhythm.]

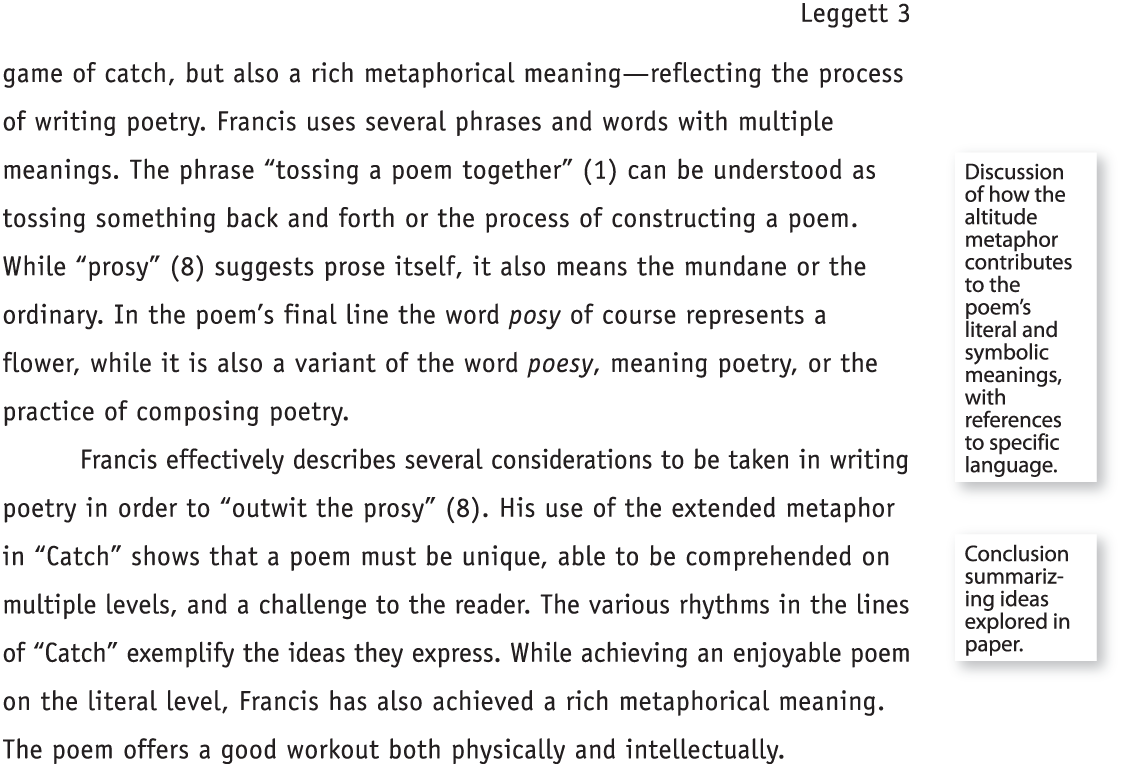

Paragraph 5. While altitudes when referring to the game of catch means how high an object is thrown, in poetry it could refer to the level of diction, lofty or down-to-earth, formal or informal. It suggests also the levels at which a poem can be comprehended, the literal as well as the interpretive. In Francis’s game of catch, the ball is thrown high to make the player reach, low to open quotes make him stoop close quotes (4), or open quotes Over his head [to] make him scramble close quotes (10), implying that the player should have to exert himself to catch it. So too, then, should the reader of poetry put great effort into understanding the full meaning of a poem. Francis exemplifies this consideration in writing poetry by giving open quotes Catch close quotes not only an enjoyable literal meaning concerning the (ellipsis) [A corresponding margin note reads, Analysis of the meaning of altitudes in the poem.] [The word,’ altitude’ is italicised.]

Text continues as follows:

(Ellipsis) game of catch, but also a rich metaphorical meaning—reflecting the process of writing poetry. Francis uses several phrases and words with multiple meanings. The phrase open quotes tossing a poem together close quotes (1) can be understood as tossing something back and forth or the process of constructing a poem. While open quotes prosy close quotes (8) suggest prose itself, it also means the mundane or the ordinary. In the poem’s final line the word (begin italics) posy (end italics) of course represents a flower, while it is also a variant of the word (begin italics) poesy (end italics), meaning poetry, or the practice of composing poetry. [A corresponding margin note reads, Discussion of how the altitude metaphor contributes to the poem’s literal and symbolic meanings, with references to specific language.]

Paragraph 6. Francis effectively describes several considerations to be taken in writing poetry in order to open quotes outwit the prosy close quotes (8). His use of the extended metaphor in open quotes Catch close quotes shows that a poem must be unique, able to be comprehended on multiple levels, and a challenge to the reader. The various rhythms in the lines of open quotes Catch close quotes exemplify the ideas they express. While achieving an enjoyable poem on the literal level, Francis has also achieved a rich metaphorical meaning. The poem offers a good workout both physically and intellectually. [A corresponding margin note reads, Conclusion summarizing ideas explored in paper.]

The line reads as follows:

Francis, Robert. Open quotes Catch close quotes. [Italics] The Compact Bedford Introduction to Literature [end Italics], edited by Michael Meyer and D. Quentin Miller, 12th ed., Bedford forward slash St. Martin’s, 2019, p. 513 hyphen 14.

[The book name is italicised.]

Before beginning your own writing assignment on poetry, you should review Chapter 43, “Reading and the Writing Process,” which provides a step-by-step overview of how to choose a topic, develop a thesis, and organize various types of writing assignments. If you are using outside sources in your paper, you should make sure that you are familiar with the conventional documentation procedures described in Chapter 44, “The Literary Research Paper.”

How does the speaker’s description in Francis’s “Catch” of what readers might expect from reading poetry compare with the speaker’s expectations concerning fiction in the next poem by Philip Larkin?

Philip Larkin (1922–1985)

A Study of Reading Habits 1964

When getting my nose in a book

Cured most things short of school,

It was worth ruining my eyes

To know I could still keep cool,

And deal out the old right hook

To dirty dogs twice my size.

Later, with inch-thick specs,

Evil was just my lark:

Me and my cloak and fangs

Had ripping times in the dark.

The women I clubbed with sex!

I broke them up like meringues.

Don’t read much now: the dude

Who lets the girl down before

The hero arrives, the chap

Who’s yellow and keeps the store,

Seem far too familiar. Get stewed:

Books are a load of crap.

In “A Study of Reading Habits,” Larkin distances himself from a speaker whose sensibilities he does not wholly share. The poet — and many readers — might identify with the reading habits described by the speaker in the first twelve lines, but Larkin uses the last six lines to criticize the speaker’s attitude toward life as well as reading. The speaker recalls in lines 1–6 how as a schoolboy he identified with the hero, whose virtuous strength always triumphed over “dirty dogs,” and in lines 7–12 he recounts how his schoolboy fantasies were transformed by adolescence into a fascination with violence and sex. This description of early reading habits is pleasantly amusing, because many readers of popular fiction will probably recall having moved through similar stages, but at the end of the poem the speaker provides more information about himself than he intends to.

As an adult the speaker has lost interest in reading because it is no longer an escape from his own disappointed life. Instead of identifying with heroes or villains, he finds himself identifying with minor characters who are irresponsible and cowardly. Reading is now a reminder of his failures, so he turns to alcohol. His solution, to “Get stewed” because “Books are a load of crap,” is obviously self-destructive. The speaker is ultimately exposed by Larkin as someone who never grew beyond fantasies. Getting drunk is consistent with the speaker’s immature reading habits. Unlike the speaker, the poet understands that life is often distorted by escapist fantasies, whether through a steady diet of popular fiction or through alcohol. The speaker in this poem, then, is not Larkin but a created identity whose voice is filled with disillusionment and delusion.

The problem with Larkin’s speaker is that he misreads books as well as his own life. Reading means nothing to him unless it serves as an escape from himself. It is not surprising that Larkin has him read fiction rather than poetry because poetry places an especially heavy emphasis on language. Fiction, indeed any kind of writing, including essays and drama, relies on carefully chosen and arranged words, but poetry does so to an even greater extent. Notice, for example, how Larkin’s deft use of trite expressions and slang characterizes the speaker so that his language reveals nearly as much about his dreary life as what he says. Larkin’s speaker would have no use for poetry.

What is “unmistakable” in poetry (to use Robinson’s term again) is its intense, concentrated use of language — its emphasis on individual words to convey meanings, experiences, emotions, and effects. Poets never simply process words; they savor them. Words in poems frequently create their own tastes, textures, scents, sounds, and shapes. They often seem more sensuous than ordinary language, and readers usually sense that a word has been hefted before making its way into a poem. Although poems are crafted differently from the ways a painting, sculpture, or musical composition is created, in each form of art the creator delights in the medium. Poetry is carefully orchestrated so that the words work together as elements in a structure to sustain close, repeated readings. The words are chosen to interact with one another to create the maximum desired effect, whether the purpose is to capture a mood or feeling, create a vivid experience, express a point of view, narrate a story, or portray a character.

Here is a poem that looks quite different from most verse, a term used for lines composed in a measured rhythmical pattern, which are often, but not necessarily, rhymed.

Mountain Graveyard 1979

for the author of “Slow Owls”

Spore Prose

stone |

notes |

slate |

tales |

sacred |

cedars |

heart |

earth |

asleep |

please |

hated |

death |

Though unconventional in its appearance, this is unmistakably poetry because of its concentrated use of language. The poem demonstrates how serious play with words can lead to some remarkable discoveries. At first glance “Mountain Graveyard” may seem intimidating. What, after all, does this list of words add up to? How is it in any sense a poetic use of language? But if the words are examined closely, it is not difficult to see how they work. The wordplay here is literally in the form of a game. Morgan uses a series of anagrams (words made from the letters of other words, such as read and dare) to evoke feelings about death. “Mountain Graveyard” is one of several poems that Morgan has called “Spore Prose” (another anagram) because he finds in individual words the seeds of poetry. He wrote the poem in honor of the fiftieth birthday of another poet, Jonathan Williams, the author of “Slow Owls,” whose title is also an anagram.

The title, “Mountain Graveyard,” indicates the poem’s setting, which is also the context in which the individual words in the poem interact to provide a larger meaning. Morgan’s discovery of the words on the stones of a graveyard is more than just clever. The observations he makes among the silent graves go beyond the curious pleasure a reader experiences in finding that the words sacred cedars, referring to evergreens common in cemeteries, consist of the same letters. The surprise and delight of realizing the connection between heart and earth are tempered by the more sober recognition that everyone’s story ultimately ends in the ground. The hope that the dead are merely asleep is expressed with a plea that is answered grimly by a hatred of death’s finality.

Little is told in this poem. There is no way of knowing who is buried or who is looking at the graves, but the emotions of sadness, hope, and pain are unmistakable — and are conveyed in fewer than half the words of this sentence. Morgan takes words that initially appear to be a dead, prosaic list and energizes their meanings through imaginative juxtapositions.

The following poem also involves a startling discovery about words. With the peculiar title “l(a,” the poem cannot be read aloud, so there is no sound, but is there sense, a theme — a central idea or meaning — in the poem?

l(a 1958

l(a

le

af

fa

ll

s)

one

l

iness

Considerations for Critical Thinking and Writing

- FIRST RESPONSE. Discuss the connection between what appears inside and outside the parentheses in this poem.

- What does Cummings draw attention to by breaking up the words? How do this strategy and the poem’s overall shape contribute to its theme?

- Which seems more important in this poem — what is expressed or the way it is expressed?

Although “Mountain Graveyard” and “l(a” do not resemble the kind of verse that readers might recognize immediately as poetry on a page, both are actually a very common type of poem, called the lyric, usually a brief poem that expresses the personal emotions and thoughts of a single speaker. Lyrics are often written in the first person, but sometimes — as in “Mountain Graveyard” and “l(a” — no speaker is specified. Lyrics present a subjective mood, emotion, or idea. Very often they are about love or death, but almost any subject or experience that evokes some intense emotional response can be found in lyrics. In addition to brevity and emotional intensity, lyrics are also frequently characterized by their musical qualities. The word lyric derives from the Greek word lyre, meaning a musical instrument that originally accompanied the singing of a lyric. Lyric poems can be organized in a variety of ways, such as the sonnet, elegy, and ode (see Chapter 24), but it is enough to point out here that lyrics are an extremely popular kind of poetry with writers and readers.

The following anonymous lyric was found in a sixteenth-century manuscript.

Western Wind ca. 1500

Western wind, when wilt thou blow,

The small rain down can rain?

Christ, if my love were in my arms,

And I in my bed again!

This speaker’s intense longing for his lover is characteristic of lyric poetry. He impatiently addresses the western wind that brings spring to England and could make it possible for him to be reunited with the woman he loves. We do not know the details of these lovers’ lives because this poem focuses on the speaker’s emotion. We do not learn why the lovers are apart or if they will be together again. We don’t even know if the speaker is a man. But those issues are not really important. The poem gives us a feeling rather than a story.

A poem that tells a story is called a narrative poem. Narrative poetry may be short or very long. An epic, for example, is a long narrative poem on a serious subject chronicling heroic deeds and important events. Among the most famous epics are Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, the Old English Beowulf, Dante’s Divine Comedy, and John Milton’s Paradise Lost. More typically, however, narrative poems are considerably shorter, as is the case with the following poem, which tells the story of a child’s memory of her father.

When I Write

“There are lots of things that are going on in the world, in your room, or in that book you didn’t read for class that could set you on fire if you gave them a chance. Poetry isn’t only about what you feel, it’s about what you think, and about capturing the way the world exists in one particular moment.”

— REGINA BARRECA

Nighttime Fires 1986

When I was five in Louisville

we drove to see nighttime fires. Piled seven of us,

all pajamas and running noses, into the Olds,

drove fast toward smoke. It was after my father

lost his job, so not getting up in the morning

gave him time: awake past midnight, he read old newspapers

with no news, tried crosswords until he split the pencil

between his teeth, mad. When he heard

the wolf whine of the siren, he woke my mother,

and she pushed and shoved us all into waking. Once roused we longed for burnt wood

and a smell of flames high into the pines. My old man liked

driving to rich neighborhoods best, swearing in a good mood

as he followed fire engines that snaked like dragons

and split the silent streets. It was festival, carnival.

If there were a Cadillac or any car

in a curved driveway, my father smiled a smile

from a secret, brittle heart.

His face lit up in the heat given off by destruction

like something was being made, or was being set right.

I bent my head back to see where sparks

ate up the sky. My father who never held us

would take my hand and point to falling cinders that

covered the ground like snow, or, excited, show us

the swollen collapse of a staircase. My mother

watched my father, not the house. She was happy

only when we were ready to go, when it was finally over

and nothing else could burn.

Driving home, she would sleep in the front seat

as we huddled behind. I could see his quiet face in the

rearview mirror, eyes like hallways filled with smoke.

This narrative poem could have been a short story if the poet had wanted to say more about the “brittle heart” of this unemployed man whose daughter so vividly remembers the desperate pleasure he took in watching fire consume other people’s property. Indeed, a reading of William Faulkner’s famous short story “Barn Burning” (available in Selected Short Stories of William Faulkner, Modern Library, 1993) suggests how such a character can be further developed and how his child responds to him. The similarities between Faulkner’s angry character and the poem’s father, whose “eyes [are] like hallways filled with smoke,” are coincidental, but the characters’ sense of “something … being set right” by flames is worth comparing. Although we do not know everything about this man and his family, we have a much firmer sense of their story than we do of the story of the couple in “Western Wind.”

Although narrative poetry is still written, short stories and novels have largely replaced the long narrative poem. Lyric poems tend to be the predominant type of poetry today. Regardless of whether a poem is a narrative or a lyric, however, the strategies for reading it are somewhat different from those for reading prose. Try these suggestions for approaching poetry.

Suggestions for Approaching Poetry

- Assume that it will be necessary to read a poem more than once. Give yourself a chance to become familiar with what the poem has to offer. Like a piece of music, a poem becomes more pleasurable with each encounter.

- Pay attention to the title; it will often provide a helpful context for the poem and serve as an introduction to it. Larkin’s “A Study of Reading Habits” is precisely what its title describes.

- As you read the poem for the first time, avoid becoming entangled in words or lines that you don’t understand. Instead, give yourself a chance to take in the entire poem before attempting to resolve problems encountered along the way.

- On a second reading, identify any words or passages that you don’t understand. Look up words you don’t know; these might include names, places, historical and mythical references, or anything else that is unfamiliar to you.

- Read the poem aloud (or perhaps have a friend read it to you). You’ll probably discover that some puzzling passages suddenly fall into place when you hear them. You’ll find that nothing helps, though, if the poem is read in an artificial, exaggerated manner. Read in as natural a voice as possible, with slight pauses at line breaks. Silent reading is preferable to imposing a te-tumpty-te-tum reading on a good poem.

- Read the punctuation. Poems use punctuation marks — in addition to the space on the page — as signals for readers. Be especially careful not to assume that the end of a line marks the end of a sentence, unless it is concluded by punctuation.

- Paraphrase the poem to determine whether you understand what happens in it. As you work through each line of the poem, a paraphrase will help you to see which words or passages need further attention.

- Try to get a sense of who is speaking and what the setting or situation is. Don’t assume that the speaker is the author; often it is a created character.

- Assume that each element in the poem has a purpose. Try to explain how the elements of the poem work together.

- Be generous. Be willing to entertain perspectives, values, experiences, and subjects that you might not agree with or approve of. Even if baseball bores you, you should be able to comprehend its imaginative use in Francis’s “Catch.”

- Try developing a coherent approach to the poem that helps you to shape a discussion of the text. See Chapter 42, “Critical Strategies for Reading,” to review formalist, biographical, historical, psychological, feminist, and other possible critical approaches.

- Don’t expect to produce a definitive reading. Many poems do not resolve all the ideas, issues, or tensions in them, and so it is not always possible to drive their meaning into an absolute corner. Your reading will explore rather than define the poem. Poems are not trophies to be stuffed and mounted. They’re usually more elusive. And don’t be afraid that a close reading will damage the poem. Poems aren’t hurt when we analyze them; instead, they come alive as we experience them and put into words what we discover through them.

A list of more specific questions using the literary terms and concepts discussed in the following chapters begins in “Writing about Poetry.” That list, like the suggestions just made, raises issues and questions that can help you read just about any poem closely. These strategies should be a useful means for getting inside poems to understand how they work. Furthermore, because reading poetry inevitably increases sensitivity to language, you’re likely to find yourself a better reader of words in any form — whether in a novel, a newspaper editorial, an advertisement, a political speech, or a conversation — after having studied poetry. In short, many of the reading skills that make poetry accessible also open up the world you inhabit.

You’ll probably find some poems amusing or sad, some fierce or tender, and some fascinating or dull. You may find, too, some poems that will get inside you. Their kinds of insights — the poet’s and yours — are what Emily Dickinson had in mind when she defined poetry this way: “If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me, I know that it is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that it is poetry.” Dickinson’s response may be more intense than most — poetry was, after all, at the center of her life — but you, too, might find yourself moved by poems in unexpected ways. In any case, as Edwin Arlington Robinson knew, poetry is, to an alert and sensitive reader, “eventually unmistakable.”