We the people are the rightful masters of both Congress and the courts, not to overthrow the Constitution but to overthrow the men who pervert the Constitution.[194]

Abraham Lincoln

Chapter 8 explained that the economic revolutions resulted in shifts in plutocratic economic power. Moreover, each one of these powers, whether feudal, mercantilist, industrial, transport or technological, sought in some fashion and to some degree to increase its power so as to restrict competition in order to earn an incrementally higher return than obtainable by a competitive market, thereby earning an incremental parasitic profit. However, aside from their attempts to restrict competition, those plutocracies operated essentially sound business models. The banking plutocracy has had similar motives with a difference.

The banking plutocracy, although it provided a service required by the market place, financing, it used a defunct and chronically unstable financing model to do so, based on usury instead of equity financing. Hence, for the big banks gaining political power was not a just matter of earning an incremental parasitic profit as with the rest of the plutocracies, but a question of survival. The unified theory of macroeconomic failure diagnosed the intrinsic negative externality of banking as the prime cause of periodic waves of bank failures and economic crises. A large negative externality meant that banking was not economically viable and, therefore, could not survive on purely economic grounds; therefore, it needed a high degree of communist style government support to prop it up, which in turn required a correspondingly high degree of banking political power to enforce the absurd economic policies it called for. In other words, banking demanded large government subsidies to maintain its flawed and parasitic banking superstructure, which necessitated considerable banking power to enforce it. Moreover, as the usurious revolution developed and its range of usurious products expanded, the indebtedness of banking and the economy and with it the negative externality of usury grew exponentially, requiring the banks to have ever more power to ensure the ready availability of ever larger government bailouts Extending this trend further, one must inevitably conclude that at some point, the subsidy would become so massive that the big banks must assume absolute political power, making a banking dictatorship an absolute necessity for their continued survival. Indeed, many Western countries have already passed this mark. It is in this context that we must understand the birth of the Federal Reserve, its growing power, and its progressive assumption of the economic powers of the executive and legislative branches of government. This perspective also sheds additional light on the motives behind the counter-revolution discussed earlier.

The Birth of the Federal Reserve

The big banks orchestrated an intense lobbying effort, led by J. P. Morgan Bank, to establish a private central bank. They succeeded in getting a bill through the House of Representatives, but a majority of the senators repeatedly rejected it. Its advocates saw their opportunity on December 23, 1913, as the ranks of the opposing senators thinned, departing from Washington, DC, to join their far-flung families for Christmas celebrations. Thus, the resolution to establish the Federal Reserve passed on Christmas Eve. Establishing a safe harbor for usurious banks on the most sacred of nights was beyond ominous.

The Federal Reserve is a mediaeval concept. It mimicked the Bank of England, a privately owned central bank established centuries earlier in 1694. Back then, government and private interests overlapped, but times had changed. In 1858, the British Parliament passed the Government of India Act, which among other things, nationalized the operations of the East India Company, marking the beginning of the formal separation between private interests and the affairs of state in Great Britain. Alas, the formal divorce between the British government and its private central bank would take a while longer. Hence, for powerful American bankers to seek to encroach on and meddle in the economic affairs of the American state in the 20th century through a private central bank was a march against time toward a feudal past. It has been the most detrimental act to public interest.

The Bank of England used gold for its currency, with silver playing an auxiliary role. Hence, it could not create physical currency. By the late 19th century, the inflexibility of managing national economies under a gold standard was becoming clear. The Great Depression provided the impetus to make the switch to fiat currencies. Several countries, including Great Britain, abandoned the gold standard by 1931, but the United States only devalued the gold content of the dollar.

In July 1944, in the midst of World War II, forty-four allied countries held feverish talks in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in the United States, culminating in the signing of the Bretton Woods Agreement. It established a new international monetary system based on the US dollar, initially with fixed exchange rates; the US government promised member central banks dollar-gold convertibility if they so desired. The abandonment of the gold standard, despite a slender link remaining, was a game-changer because the dollar became a fiat currency. Money creation and monetary policy became key tools in conducting national economic policy, making it more essential than ever for central bank ownership and control to be in government hands—particularly in the United States, the center of the new international monetary order.

In 1946, after 252 years of private ownership, a British labor government nationalized the politically and economically powerful Bank of England. The new fiat currency regime dictated this measure to uphold the sovereignty of the British state by preventing the bankers from assuming economic powers of the state in violation of democratic principles.

There was another critical reason for nationalizing the Bank of England: to preempt conflicts between fiscal and monetary policies. The ease of creating and destroying fiat currency required monetary policy synchronization with fiscal policy to avoid catastrophic policy contradictions and to ensure maximum economic effectiveness. For the same reason no responsible insurance company insures an airplane or ship with two captains: two minds at the helm cause accidents. Hence, economic sanity requires one authority in charge of fiscal and monetary policies to avoid schizophrenic economic policies.

In the early 1970s, the US government discarded the last remaining straw of the gold standard by suspending the dollar-gold convertibility, which ended Bretton Woods. It was another opportunity to synchronize America’s fiscal and monetary policies under one roof. Alas, it was lost in the distractions of the Vietnam War, a Nixon presidency in crisis, and the oil shock of 1973. Banking interests saw the confusion as an opportunity to expand their authority by stripping away more powers from the government. They lobbied for and obtained complete Federal Reserve independence from the government. One consequence is today’s usurious capitalism.[195]

The Riddle of the Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve is an enigma. Many things about it are confusing. Most people presume the US federal government owns the Federal Reserve System, disbelieving that it is a private entity. To most people a privately owned central bank is a contradiction of terms—no less absurd than a square circle. Remarkably, more than a century after its establishment, the American public is still in the dark about the most basic facts concerning their private central bank.

This is principally the fault of the Fed itself and the confusing information it circulates. Let us take an example. On November 2, 2014, the Federal Reserve website carried a publication titled “Who Owns the Federal Reserve?”[196] It states, “…the Federal Reserve System fulfills its public mission as an independent entity within government. It is not owned by anyone and is not a private, profit-making institution.” The statement “not owned by anyone” is absurd because all corporations must have owners.

The same publication goes on to state that “dividends are, by law, 6 percent per year.” This refutes the earlier statement that “It is not owned by anyone…” because dividends are distributed to the owners (i.e., the shareholders). If the Fed is in fact “not owned by anyone,” then who has been receiving the billions of dollars in annual dividends?

By law, the shareholders of the twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks are banks; this means the statement “the Federal Reserve System…[is] not…a private [entity]” is misleading, because it is a private corporation owned by banks.

The statement “[it] is not a private, profit-making institution” is another yarn. Clearly, dividends are profit distributions; therefore, it takes “profit-making” to distribute dividends, whereas “not a private, profit-making institution” gives the impression that it is a charity, but charities do not distribute dividends to their shareholders.

In this age, high standards of transparency are expected, whereas this Fed publication is baffling and misleading. The Fed would serve public information better by withdrawing all such confusing publications and replacing them with ones that accurately present the facts, without a shade of vagueness. We will have more to say about this publication later.

Another riddle of the Federal Reserve—a private entity—is that it holds a monopoly over the creation of money and the conduct of monetary policy, despite the prevailing US antitrust statutes in 1913 specifically enacted to prevent and to break up monopolies and cartels. Moreover, bank representatives sit on the boards of the Regional Reserve Banks, with the power to decide which competitive bank to save or sink, entailing unbound conflict of interest—a flagrant violation of the principles of fair competition and a level playing field.

The complex structure of the Federal Reserve System is a yet another riddle. The mission of the twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks has no rational parallel in the annals of modern management because they are charged with supervising their shareholders. This is no less absurd than tasking a child with responsibility for supervising his (her) parents. More precisely, a regional Federal Reserve Bank must supervise the banks in its region, which are not only its shareholders but also appoint its board of directors with ultimate power for setting policy and appointing the top management. In other words, the management structure of a regional Federal Reserve Bank represents an infinite loop, whereby the member banks within a region supervise the operations of the regional Federal Reserve Bank and the latter in turn supervises the operations of those banks. This type of management structure is not common for good reason: it is preposterous. The failure of thousands of banks, despite Fed supervision, testifies to its absurdity. The way to cut this weird loop and improve the survival rate of the banks is to have government ownership of the Regional Reserve Banks, as in the rest of the world.

The Direct Cost of the Federal Reserve

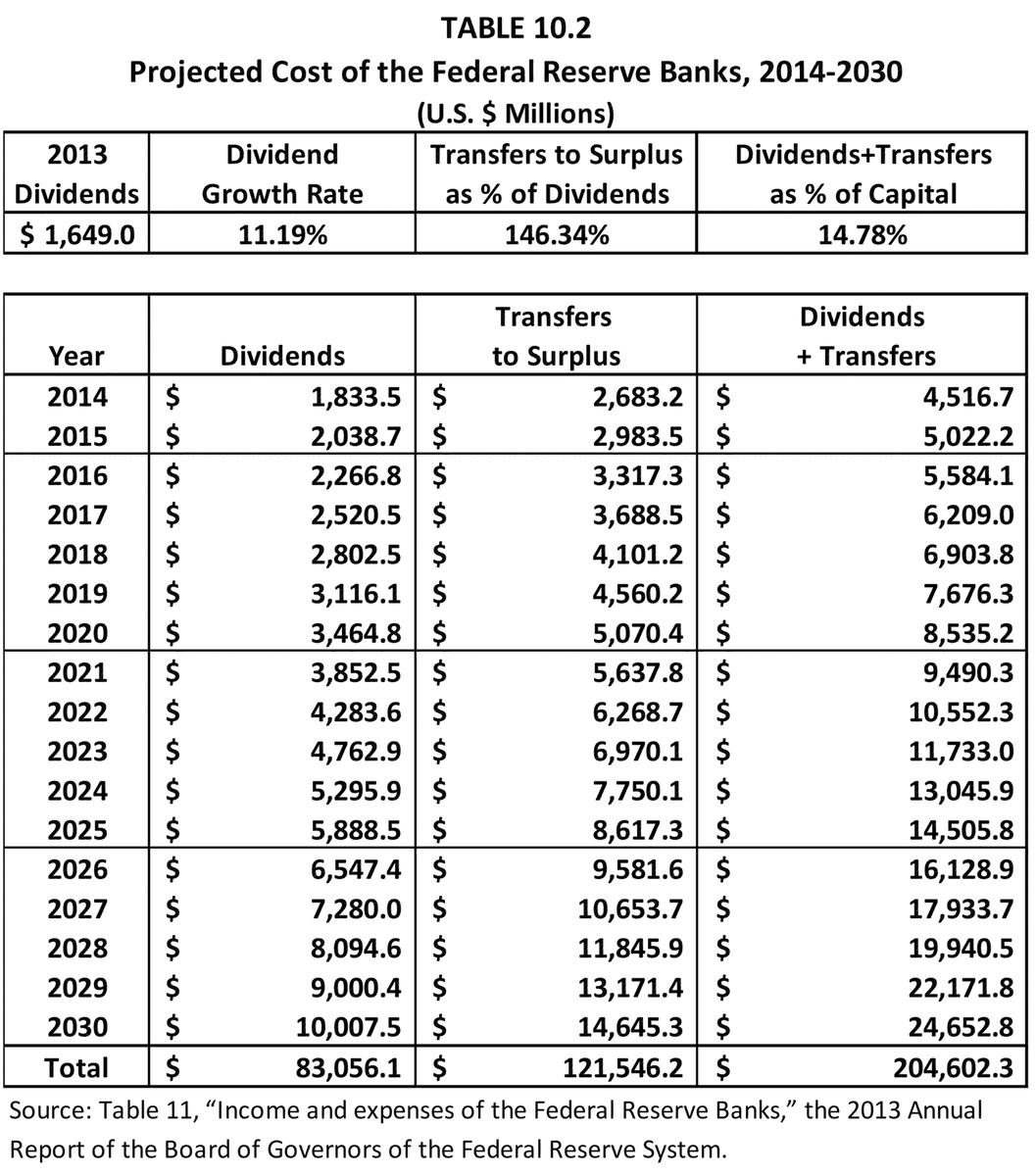

Another riddle of the Federal Reserve is its direct cost to taxpayers. The previously cited Fed publication “Who Owns the Federal Reserve?” gives the dividends as 6 percent of capital, but it makes no mention of a larger sum: “Net Transfers to Surplus.” The 2013 Annual Report of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System coincided with the Fed’s centennial; hence, it contains interesting facts about the financial history of the Fed.[197] The annual report shows that, since its inception, “Net Transfers to Surplus” have totaled more than $27,506.8 million compared to total dividends at $18,796.2 million, bringing the total direct cost to $46,303.1 million. In other words, “Net Transfers to Surplus” have averaged approximately 146.34 percent of dividends. Thus, a full disclosure of the direct cost of the Federal Reserve is 14.78 percent of the capital, not just 6 percent in dividends. The Federal Reserve does not distribute the “Net Transfers to Surplus” but uses it to increase its capital, which increases the dollar amount of its 6 percent dividend (see Table 10.1).

Table 10.1 provides a partial summary of Table 11 titled “Income and Expenses of the Federal Reserve Banks” in the Fed 2013 annual report. It shows that between 1917 and 2013, dividends increased from $1.7 million to $1,649.3 million, a 242-fold increase. The Federal Reserve’s direct cost to taxpayers has been rising much faster than the growth in gross domestic product (GDP) and it has accelerated following the dismantling of the banking regulations.

To assess the effect of the political shift to the right of the counter-revolution on the Fed’s dividend growth rate, we considered three periods: 1917-1982 (pre-deregulation), 1982-1999 (a period of progressive deregulation), and 1999-2013 (post-deregulation). Up to 1982, dividend growth was generous at 6.05 percent per annum. It accelerated to 9.54 percent per annum between 1983 and 1999. After 1999, dividend growth accelerated further to 11.19 percent per annum. Remarkably, dividends growth accelerated as inflation was falling. One possible explanation of the accelerating growth in dividends is the growing political power of the banks, making them unconcerned about any public outcry.

Thus, the total cost of the Federal Reserve is 14.78 percent of capital (6 percent dividends + 8.78 percent Net Transfers to Surplus). Some financial scholars might dispute the theoretical basis for this calculation because the Net Transfers to Surplus are not distributed to the shareholders. The generally accepted alternative calculation is the total return to the shareholders, representing the dividend yield plus its growth rate. Post-deregulation, the dividend growth rate reached 11.19 percent per annum, bringing the total returns to the shareholders to 17.19 percent (6 percent dividends + 11.19 percent growth). This is a phenomenally high reward for assuming practically no risk. Compared to the return on long-term Treasuries, a total return of 17.19 percent represents great extravagance with taxpayers’ money.

To grasp this degree of extravagance, one needs to project it into the future, say to 2030. Table 10.2 assumes dividends will continue to grow at 11.19 percent per annum and “Net Transfers to Surplus” continue to average 146.34 percent of dividends. Table 10.2 projects the cumulative direct cost of the Federal Reserve for the period 2014-2030 at $204,602.3 million, a prohibitive cost to taxpayers and tax exempt to boot.

Doubtless, the impoverished in America deserve this money more than the banks. Earmarking it for the needy is not only a moral choice, but also economically rational. The financial burden of supporting a private Federal Reserve System for the benefit of its shareholding banks and their wealthy shareholders is too onerous for a democracy. It is clearly more cost-effective to nationalize the Federal Reserve System. Alas, this is hardly the full economic cost of the Federal Reserve.

Theoretically, timely countercyclical monetary policies can smooth economic cycles; however, what are the odds of its success? Given a time lag of about one year between a monetary policy action and its effects taking hold, a central bank needs to forecast changes in the direction of the economy about a year in advance. Moreover, economic data, the raw material for decision-making, are only available several months in arears and are subject to several revisions, further extending the time horizon of the required forecast. Furthermore, forecasts are notoriously inaccurate, and forecasting economic turning points, although most useful, is also the most challenging. Monetary authorities’ use of a wrong or inaccurate forecast risks increasing instead of dampening cyclical fluctuations.

In addition to the requisite economic and forecasting skills, central bankers must be immune to the influence of third parties, especially the big banks, holding the prospect of future employment with lavish pay. Prolonging an expansion also requires walking a tightrope of applying monetary brakes early enough to abort speculative bubbles and to prevent the economy from overheating, yet lightly enough to avoid tipping it into a recession; this also demands psychological immunity from the pressures of the media and the public.

Thus, correct monetary policy requires the foresight of a sage, the nobility of an angel, and the courage of a lion. These are rare qualities indeed, and not just among central bankers. Hence, even under the most favorable assumptions, there can be no assurance a priori that monetary policy will be countercyclical and stabilizing, instead of pro-cyclical and destabilizing. In other words, we are expecting central bankers to perform feats that are beyond the abilities of most humans.

Professor Friedman understood the difficulties of implementing an effective countercyclical monetary policy.[198] Hence, he advised limiting monetary policy to a steady growth in the money supply throughout the cycle to achieve the more modest objective of accommodating economic growth and its associated frictional inflation. Such a policy is less demanding, but not without its own problems. It presumes that the velocity of the circulation of money is stable over an economic cycle, even though the evidence suggests that it fluctuates—widely.

Intuitively, one would expect the velocity of circulation to pick up during an economic expansion and to fall during a contraction. For example, rising interest rate during an expansion increases the opportunity cost of holding cash, inducing a reduction in idle balances and a corresponding increase in the velocity of circulation, and vice versa. Thus, a steady expansion in the money supply would be doubly expansionary during an expansion and ineffective during a contraction. Furthermore, the introduction of new technologies (e.g., credit cards, Internet transfers) tends to increase the velocity of circulation, further complicating the analysis.

Finally, the behavior of the economic actors can reinforce or neutralize a monetary policy. Thus, the Fed’s gigantic quantitative easing has had a minimal stimulative effect because many banks, fearing a rise in credit risk, have used the near-zero cost of funds to earn a spread on Treasury bonds instead of expanding credit.

The difficulties of conducting an effective monetary policy are clear. Yet, even allowing for this factor, the Federal Reserve monetary policy is an inexplicably consistent failure, unmitigated by any randomness. As a result, the cost of the Federal Reserve monetary policy to the US economy is phenomenally greater than its direct cost, as estimated in the previous section.

We can only speculate on the reasons behind the appalling performance of the Federal Reserve. For one thing, the representatives of the member banks sit on the boards of the Federal Reserve’s regional banks and participate in setting monetary policy. Yet, banks’ past performance demonstrates that they are incompetent in managing the affairs of their own banks, requiring constant Fed support and periodic government bailouts to survive. Hence, it is economically suicidal to have those same economic “wizards” responsible for running the monetary affairs of the United States, the largest economy in the world.

In 1963, Professor Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz published their treatise, A Monetary History of the United States. Their study showed that the Federal Reserve had pushed the US economy into the Great Depression by tightening monetary policy during a contraction—an unfathomable error. In a 2002 speech, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke stated, “Let me end my talk by abusing slightly my status as an official representative of the Federal Reserve. I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression. You’re right, we did it. We’re very sorry. But thanks to you, we won’t do it again.”[199] Based on his examination of the record of Fed monetary policy, Professor Friedman recommended abolishing the Federal Reserve altogether.

Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke stopped short of explaining why they “did it.” Neither did Professor Friedman dwell on other possible reasons for the Fed’s peculiar actions, besides gross incompetence. The Fed’s actions would seem to be perplexing to say the least. But it is even spookier to realize that the Fed has consistently repeated an irrational policy.

Table 11.1 in Chapter 11 presents the seven economic contractions in the twenty-nine years following the creation of the Fed in 1913 until 1942, the start of American mobilization for World War II. Of these, three major contractions in 1920-1921, 1929-1933 (the Great Depression), and 1937-1938 appear to have been caused by tight monetary policy. The Fed appears incapable of learning from the economic crises it seeds, but is that a plausible explanation?

We could speculate about other possible causes for Fed policy during the Great Depression for example. Did the Communist Party USA want the US economy to plunge in depression as a prelude to revolution? They almost certainly did, but it is unthinkable that the Fed had communist leanings, swelling the armies of the unemployed to bring about a communist takeover of America, even if the Fed’s actions increased that risk.

That aside, every US recession and depression thinned the number of US banks. The Great Depression alone bankrupted more than nine thousand banks.[200]The huge reduction in competition increased the market shares of the banks that survived. Conflict of interest was present then as now, but we have no evidence that the Fed purposely engineered those contractions to increase the market share of the big banks by shrinking their competition.

The Fed went back to its tight monetary policies during the recessions in 1973-1975, 1980, and 1981-1982.[201] In all three instances, a tight monetary policy was inappropriate for containing cost-push inflation and a neutral stance would have been more appropriate.

The Federal Reserve shifted its monetary policy from overly restrictive to overly expansionary in the 1990s. What prompted that dramatic reversal is a mystery. Artificially low interest rates launched an era of speculative bubbles and crashes. By the late 1990s, easy monetary policy helped lift NASDAQ to a highly inflated level. The Fed then reversed course, precipitating a recession. The dot-com crash of 2000, as measured by NASDAQ, was comparable to the Dow’s crash during the Great Depression, only sharper.

Following that crash, the Fed went back to lowering interest rates; its effect on the United States was modest growth, while fueling another speculative bubble—this time in housing. With the Fed’s oversight, banks raised hundreds of billions of dollars in collateralized mortgage debt (CMD), pumping the housing bubble further. In the face of public concern over a housing bubble, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke assured the public that a crash in housing had never happened across the United States, overlooking the fact that there is always a first time. The Fed kept pumping cheap money and inflating housing prices to exhilarating heights. It then abruptly reversed course by raising interest rates, which helped precipitate the housing crash in late 2007. The stock market crashed in sympathy, falling by almost as much as it did during the 1973-1975 recession.

In the fourth quarter of 2008, the Fed dramatically reversed course yet again, this time to save the big banks from bankruptcy. Its monetary policy was far easier than ever before. US growth remained anemic; however, by 2015, the Fed succeeded in inflating a gargantuan bond bubble—far bigger than any past stock market or real estate bubbles. Thus, before the debris from the previous crash had settled, the Fed was back to priming the American economy for another cataclysm.

At best, the Fed’s monetary policy appears naïve: fast forward followed by sharp braking and reversing, then fast forward again. Nothing could be simpler. In less than two decades, two renowned Fed chairs with superb academic credentials used easy monetary policies to inflate giant asset bubbles in all three major asset classes: stocks, real estate, and bonds, respectively.

Alan Greenspan’s reign as Fed chair lasted almost two decades, from August 11, 1987, until January 31, 2006. He is credited with overseeing the comprehensive dismantling of banking regulations in America. His other major accomplishments included pumping the Internet bubble then bursting it, followed by pumping the housing bubble. His term ended before he could burst the second bubble.

The bubble baton passed to his successor, Ben Bernanke, whose reign as Fed chairman lasted eight years, from February 1, 2006, to January 31, 2014. Bernanke’s monetary policy was a continuation of his predecessor’s: pumping two asset bubbles and bursting one in nearly as many years. After fully inflating and bursting the housing bubble, he proceeded to pump the bond bubble, which he too could not finish pumping it before the end of his term. Both men were great bubble makers and blasters—perhaps the most outstanding in history. The bubble baton passed to the current Fed Chair Janet Yellen. The odds are that this pattern in Fed monetary policy of bubble pumping and bursting will continue.

Reasonable men, armed with common sense, must conclude that the Fed monetary policies are harmful to American prosperity. It will puzzle researchers for decades to come, as it has puzzled many economists for almost a century. When the next bubble bursts, it will reconfirm that the Federal Reserve’s policies are damaging to the US economy. This concern prompted Congressman Ron Paul, chair of the House of Representatives Monetary Policy Subcommittee in 2011, to propose nationalizing the Federal Reserve, which too few politicians have dared to support so far.

After four decades of relative banking sanity imposed by the Glass-Steagall Act, the big banks were eager to go back to their old ways of doing as they pleased. Stagflation in the 1970s presented the opportunity. The opening gambit began with the Federal Reserve raising interest rates, prompting the big banks to circumvent Regulation Q, which had placed a ceiling on interest rates following Glass-Steagall; they did so by establishing and expanding the so-called euro banks in offshore banking centers without limit on interest rates. In 1974, higher interest rates abroad began draining liquidity out of the United States, aggravating the US recession. Thus, the scrapping of Regulation Q began tentatively in New England in 1974, the first step in the progressive dismantling of Glass-Steagall.

The sweeping blow to Regulation Q came when the Federal Reserve, under Paul Volker, raised interest rates to absurd levels, with fed funds peaking at 20 percent and the prime rate at 21.5 percent in June 1981.[202] Even before March 1981 when President Carter signed into law the liberalization of interest rates, Volker’s high interest rate policy already made Regulation Q unsustainable. At a minimum, the Federal Reserve should have asked Congress for a temporary lifting of the interest rate ceiling, pending the return to interest rate normality. Today, one consequence of the scrapping of Regulation Q is that it legalized the punitive interest rates charged by payday loan sharks and credit card issuers.[203]

Between 1981 and 1986, the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 phased out the interest rate ceiling on all bank accounts, save demand deposits. This resulted in commercial banks biding funds away from savings and loan institutions (S&Ls), which had traditionally provided low-cost mortgage financing to the real estate sector. It precipitated a liquidity crisis for S&Ls, prompting them to call for extending the lifting of Regulation Q to them as well. However, the subsequent lifting of the interest rate ceiling was a death blow to S&Ls because it also removed the restrictions on commercial banks engaging in the mortgage business, permitting the big banks, with their lower costs of funds, to enjoy a decisive competitive advantage.

These measures produced the S&L crisis in the early 1990s, which wiped out the whole of the S&L sector, permanently extinguishing this source of competition to commercial banks.

Between 1984 and 1991, 1,400 S&Ls and 1,300 banks failed, mostly due to high interest rates and the progressive dismantling of banking regulations.[204] This rate of bank failure was alarming given it occurred in the absence of a depression and the number of banks was a fraction of their number in the 1930s. The Federal Reserve, despite playing a key role in the S&L debacle, did not extend a hand to the victims of its policies.

This bad experiment demonstrated that banking deregulation dramatically increased competition at first, followed by extensive bank failures and, ultimately, less competition and greater market concentration. Yet, the loss of all those financial institutions hardly dented the Federal Reserve’s enthusiasm for more deregulation with predicable results: smaller banks folded while the big banks increased their market shares.

By 1999, a quarter-century of lobbying by the big banks and Fed support, culminated in Congress repealing what was left of Glass-Steagall. That same year, the Federal Reserve supported the passage of the Commodities Futures Modernization Act, ensuring that derivatives remained unregulated and setting the stage for devastating future predicaments.

Democracy and the Federal Reserve

As the elected representatives of the people, members of Congress are entrusted with powers that they should not surrender to private interests. Abraham Lincoln echoed this in his famous Gettysburg Address by saying “government of the people, by the people, for the people.”[205] It is the foundation of democracy. Congress probably did not intend to break Lincoln’s promise to the people by abdicating its financial powers to the Fed, but lost those powers gradually and covertly. The colossal monetary size of this congressional oversight and its constitutional violation is manifest proof that it should not continue.

The Federal Reserve System today, supported by the big banks, is sure of its economic supremacy. The Fed publication cited earlier spells out its powers: “It is considered an independent central bank because its monetary policy decisions do not have to be approved by the President or anyone else in the executive or legislative branches of government.”[206] It does not take a constitutional lawyer to conclude this is a violation of democratic principles because it implies the Fed has unlimited powers and operates without democratic oversight. The Fed’s mission statement, as it were, also circumvents the much-touted system of checks and balances in American democracy.

Ashvin Pandurangi warns about the Fed’s considerable powers in his Business Insider article, “How Did a Single Unconstitutional Agency Become the Most Powerful Organization in America.” Pandurangi notes that the President appoints the Fed’s Board of Governors by choosing from a list of candidates provided by banks; the banks also get to choose the remaining five members of the Board of Governors.[207] He notes that “the members of the Fed’s Board of Governors cannot be impeached by Congress” whereas even the President of the United States can be impeached for “high crimes and misdemeanors.”[208] In effect, the Fed’s Board of Governors have been given supreme immunity above everybody in the land. Without legal consequences, there is no legal assurance of the reliability of their testimonies before Congress, eliminating any residual effectiveness of congressional oversight of Federal Reserve activities.

Moreover, the Federal Reserve has blatantly kept Congress in the dark, making even any presumption of oversight hollow. An accident revealed the extent of Congressional marginalization. An amendment by Senator Bernie Sanders to the Wall Street reform law directed the Government Accountability Office (GAO to conduct an audit of the Federal Reserve for the first time ever.[209]

A year later, Senator Sanders’ exceptional dedication and diligence paid off. On July 21, 2011, Senator Sanders published a landmark article titled “The Fed Audit.” It stated that the first top-to-bottom audit of the Federal Reserve “uncovered eye-popping new details about how the United States provided a whopping $16 trillion in secret loans to bail out American and foreign banks and businesses during the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression.”[210]

Senator Sanders cited a July 2011 “Report to Congressional Addressees” by the GAO: “Among the investigation’s key findings is that the Fed unilaterally provided trillions of dollars in financial assistance to foreign banks and corporations…”[211]

Senator Sanders further cited that the investigative arm of Congress determined, “…that the Fed lacks a comprehensive system to deal with conflicts of interest, despite the serious potential for abuse… For example, the CEO (chief executive officer) of JP Morgan Chase served on the New York Fed’s board of directors at the same time that his bank received more than $390 billion in financial assistance from the Fed.”

Senator Sanders further stated, “JP Morgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, and Wells Fargo also received trillions of dollars in Fed loans at near-zero interest rates.” Senator Sanders further declared, “The Federal Reserve must be reformed to serve the needs of working families, not just CEOs on Wall Street.”

This astronomical sum, $16 trillion in secret loans, is bewildering. It makes one wonder whether the Fed dwells in a world of alternative reality, where it presumes there is no government, or whether we are the dwellers of that world by presuming there is. Sixteen trillion dollars in 2011 is equivalent to several years of US government tax revenue; it is more than the output of the entire United States economy. It raises important questions, such as:

• Is this gargantuan sum recoverable?

• Will Congress pass an act to recover this money?

• Has any of this money been repaid and how much?

Lending $16 trillion at a negligible interest rate—below the interest that the Fed charges the Treasury on its bonds—is a colossal subsidy to the recipients and, as such, falls within the jurisdiction of fiscal policy, which, presumably, is still outside the scope of the Federal Reserve. Giant subsidies to foreign entities are tantamount to enormous gifts, allowing them to earn trillions of dollars effortlessly, without attracting US corporate income taxes. This is extraordinary Fed generosity with US taxpayers’ money without the knowledge of Congress, the President, or the people.

A fraction of this sum would have been sufficient to solve all the problems of the mortgage borrowers and homelessness in the United States; but alas, critical social issues are not on the agenda of the Federal Reserve.

Prior to this government audit, the Federal Reserve’s annual reports had made no mention of any $16 trillion, bringing into question the relevance of the Federal Reserve annual reports and the dependability of its auditors. Predictably, the new Fed Chair Janet Yellen has reportedly objected to a new audit of the Fed.[212]

Those covert subsidies aside, the Federal Reserve’s charter does not authorize it to grant subsidies, however small, to anyone, yet it has been openly providing giant subsidies to its shareholders, the banks. The trillions of dollars in so-called “quantitative easing” are, in reality, hundreds of billions of dollars in annual interest subsidies to the big banks, without the requisite congressional vote on the matter, thereby bypassing Congress altogether. Yet, fiscal matters such as subsidies are still the responsibility of Congress, at least in appearance.

The banks, not satisfied that the Federal Reserve has acquired unlimited monetary powers, have stealthily crossed the Rubicon to assume unlimited powers over the fiscal purse strings as well. Congress, having lost its monetary powers, has discovered by sheer chance that a private central bank, controlled by the banks, has been exercising sweeping fiscal powers. Unelected bankers in charge of the Federal Reserve have been appropriating the economic powers of Congress, dwarfing the power of the state to become the supreme economic power in the United States, a problem compounded by their demonstrable economic incompetence and extreme egotism. In other words, the banks, through the Fed, are now more powerful than the combined power of the President and Congress, a sad development for democracy. The future may yet hold worse surprises.

Thus, the independence of the Federal Reserve, in addition to the damage it has been inflicting on the US economy, has been undermining democracy in the United States of America. Clearly, democracy and a private central bank cannot coexist. The prime threat to democracy is no longer the military-industrial complex, as President Eisenhower famously warned, but rather the Federal Reserve-banking complex. Senator Bernie Sanders’s conclusion that “[the] Federal Reserve must be reformed” is a watershed. As the epicenter of usury, it is remarkable how what started as a usurious immorality has initiated a chain of immoral finance, immoral economics, and immoral politics, culminating in the hijacking of democracy itself. It is high time Congress heeded the advice of Professor Milton Friedman by abolishing the Federal Reserve. The alternative is to accept the current political system of the United States: a banking dictatorship with democratic paraphernalia. The United States desperately needs a revitalized economy, which is not going to happen without reforming its democracy, which in turn requires restricting the power of the ultra-rich to the economic sphere.

Looking back, we realize that the birth of the Federal Reserve on Christmas Eve, 1913, was more ominous than anyone could have imagined.