The people who cast the votes decide nothing.

The people who count the votes decide everything.[293]

Joseph Stalin

President Franklin Roosevelt saw the fragility of democracy. “The liberty of a democracy is not safe if the people tolerate the growth of private power to a point where it becomes stronger than their democratic state,” he said. “That, in its essence, is fascism.”[294] Democracy is valuable, delicate, and, throughout history, the rarest form of government. It is conceivable that a democratic ruler could implement the wishes of his people without holding elections, but that would be rarer still. In any case, voting and elections do not a democracy make; they are merely its trappings.

Today, most Western democracies are again at a critical juncture of improving their democracies or regressing further toward plutocratic fascism, as President Franklin Roosevelt had warned. Monopolies and oligopolies already dominate many industries and economic sectors, with the big banks visibly stronger than the state, the result of an insidious and sustained plutocratic encroachment on democracy. Restraining plutocratic power requires an acute public awareness of the need for regulating the political power of excessive plutocratic wealth.

Regardless of whether a system is tribal, autocratic, aristocratic, plutocratic, elitist, feudalist, monarchist, republican, or constitutional, it is typically a blend of democracy and autocracy, with all countries standing somewhere between the theoretical extremes of absolute democracy and autocracy. Even a country like Switzerland, where citizens are obligated to vote and decide important matters directly through frequent referendums, is not a perfect democracy. The most that any democracy can hope for is to strive to get closer to the democratic ideal. Similarly, there is no pure dictatorship; there are only relative ones. Even the most absolute dictators consult with their entourage, advisors, or astrologers. The main sources of autocratic power are military, religious, political, and economic, or a combination thereof.

In Western democracies, the blend between democracy and autocracy varies, with the latter taking the form of economic power or plutocracy. An intriguing question is the relative position of the various Western countries on the democracy-plutocracy scale. As the influence of plutocracy in the political process increases, economic policies tend to serve private interests instead of public interest and the economy becomes less efficient. Assessing the relative position of a country requires calibration of its democratization relative to a benchmark. It is also possible to calibrate the democratization of a country relative to itself over time, to assess whether it is drifting toward democracy or plutocracy.

Measuring Western Democratization

In a democracy, citizens exercise their collective free will in a competitive political marketplace, where voters act as political consumers, using their votes to purchase the promises of politicians and parties.[295] The unified theory of macroeconomic failure considers the erosion of democracy symptomatic of a failure of the political marketplace, due to dwindling political competition and increasing dominance by political monopolies, duopolies, or oligopolies. It also considers a failure of the political marketplace a negative externality that is rooted in moral failure.

As with other market failures, measures such as the adoption of political laissez-faire and deregulation of the political marketplace result in predatory political competition, providing a decisive advantage to political parties with abundant financial resources that serve the plutocratic establishment, permitting them to purchase democratic leadership and control. The result is an increase in the market share of the political parties representing the wealthy and loss of representation to everybody else, a negative externality that reflects a failing political marketplace, mirrored by a corresponding deterioration in the choice of public goods and taxes. Indeed, dismantling democratic checks is a path that culminates in the dismantling of democracy itself. To check this tendency, mass consciousness and political will are required to enforce regulation of the political marketplace.

Several notable research organizations have constructed freedom and democracy indexes, including the Fraser Institute in Canada, Reporters without Borders in France, Freedom House in the United States, and the Economist Intelligence Unit in Great Britain. They conduct annual country surveys to update their ratings. Each organization has adopted a set of criteria that it judged important for the evaluation of freedom and democracy, with their primary focus being emerging democracies. For instance, the Economist Intelligence Unit computes a democracy index based on an examination of civil liberties, the conduct of elections, media freedom, the functioning of the government, voter participation, public opinion, corruption, and stability.[296]

Those surveys use a broad-brush approach to compare emerging democracies relative to Western democracies. Such an approach does not serve our purpose because one needs to detect democratic trends within Western democracies relative to one another, rather than relative to emerging democracies, requiring a finer set of criteria and the construction of an index for Western democracies specifically.

Finally, the aforementioned organizations receive direct or indirect assistance from their respective governments, making them interested parties, inclined to elevate democratic ratings of their respective countries as well as those that are similar.

An analysis of the Western democracies revealed nine factors that seemed pertinent for inclusion in a Western Democratization Index, as follows:

1. Number of Representative Political Parties—a proxy for democratic choice

2. Voter Participation—a proxy for voters’ confidence in the political process

3. Economic Policy Determination—a proxy for democratically determined economic policies

4. Economic Inequality—a proxy for lack of economic democracy

5. Inclination for War—a proxy for corruption

6. Prison Population—a proxy for social tension

7. Concentration of Media Ownership—a proxy for press coverage of alternative political views

8. Limits on Political Contributions—a proxy for the fairness of the democratic process

9. Corporate Democracy—a proxy for economic democracy in the corporate sector

The resultant index has some similarities with the ones currently in use but also some distinct differences. For example, freedom of the press, a criterion used in the present indexes, is relevant for identifying an explicit autocracy. On the other hand, a free press is available in all Western democracies, making this factor redundant and the concentration of media ownership more relevant as a proxy for coverage of diverse political views. Similarly, although the pursuit of neoclassical macroeconomic policies suggests a failing democratic process, however, its near universal adoption by Western democracies has rendered it an undiscriminating indicator of relative democracy.

On further consideration, the last three factors (Concentration of Media Ownership, Limits on Political Contributions, and Corporate Democracy), although relevant, were excluded from the computation of the Western Democratization Index, because they did not seem as crucial as the first six factors. Hence, the factors actually used in the computation of the Western Democratization Index are the following:

1. Number of Representative Political Parties

2. Voters’ Participation

3. Democratically Determined Economic Policy

4. Wealth Concentration

5. Inclination for War

6. Prison Population

As stated previously, it is possible to use a democratization index in one of two ways: to compare a country’s democracy relative to that of another that serves as a benchmark, or relative to itself over time, measured in decades. Time constraint has restricted the current analysis to the benchmark version only. Thus, it is up to interested students of political science and other researchers to apply the concept more broadly.

As the largest Western democracy, the United States was a natural choice for illustrating the democratization index. There remained choosing a suitable benchmark.

Switzerland probably enjoys the highest democratic standards, but it was judged unsuitable as a benchmark for three reasons. First, it is too small relative to the United States. Second, unlike most countries, it is neutral and does not engage in wars. Third, its democratic standards are probably too lofty for most countries. On the other hand, some political science researchers might prefer it as a benchmark precisely because it has the highest democratic standards.

Canada is another candidate, but it is also small relative to the United States.

The final choice for a democratic benchmark was Germany because it is the second largest Western democracy and enjoys good democratic credentials. Specifically, in the aftermath of World War II, Germany adopted a constitution that protects individual liberties and civil rights. In addition, it distributes political power effectively between the different branches of the government as well as the federal and state levels, thereby making it a satisfactory reference country.[297]

Democracy is just a slogan if voters have no real political choice; hence, it deserves special attention. One proxy for political choice is the number of political parties. For instance, the Soviet Union’s Communist Party included millions of members from all over the country who elected the leadership of the party and the state, but it was not a democracy because it lacked political choice with voting restricted to party members. Having just one party is tantamount to a political monopoly and, therefore, undemocratic.

Generations ago, the political plutocracies of Great Britain and the United States devised voting systems that restricted political choice to just two political parties in their respective countries. As a result, contrary to democratic norms, these two countries have been ruled by one of two parties for centuries. Occasionally, the names of those parties changed, but never their number. A two-party system offers more choice than a political monopoly, but not by much, because it is a political duopoly. Economic theory tells us that a duopoly is very similar to a monopoly, giving consumers, political and otherwise, only marginally more choice than under a monopoly.

However, in the decades before the onset of the counter-revolution, the US two-party system was providing a reasonable level of political choice. Historically, political choice in the United States has been between centrist and right-wing economic agendas. The United States has never had a leftwing socialist leader and neither party has had a socialist agenda, although conservatives on the extreme right habitually accuse centrists of being leftwing socialists or communist. Moreover, both parties have had centrists and right-wing conservative leaders, and significant leaders have had a big role in setting the economic agendas of their parties.

Thus, Republican president Theodore Roosevelt was a reformer, trustbuster, centrist, and predictably hated by the conservative establishment of the Republican Party. Democratic president Franklin Roosevelt, the most popular American leader in history and elected four times, also had a centrist economic agenda and was just as hated by the conservative establishment of the Democratic Party. Republican president Dwight Eisenhower, elected twice and very popular, also had a centrist economic agenda. Similarly, Democratic president John F. Kennedy, who became extremely popular after his narrow election, also had a centrist economic agenda. His assassination indicated he was hated by some quarters. All four presidents supported the average person and opposed the agendas of large oligopolies and monopolies; hence, the conservative establishment on both sides opposed them. Their economic policies were the best available in their time, improving the environment for competition, business profits, economic growth and democracy.

Political choice in both the United States and Great Britain has suffered following the Thatcher-Reagan counter-revolution. It succeeded in shifting the Republican Party in the United States and the Conservative Party in Great Britain from right of center to the extreme right. Paradoxically, Bill Clinton, the leader of the Democratic Party in the United States, and Tony Blair, the leader of the Labor Party in Great Britain, instead of positioning their parties in the vacant political center, mimicked their competition by moving their parties to the far right as well. Thus, in both countries, the political agendas of the competing parties became almost identical, in effect, reducing political choice to the wings of extremist right-wing parties. This is reminiscent of a customer complaining about Ford cars having a limited choice of color, to which Henry Ford famously replied, “You can have any color you like, as long as it is black.” Indeed, when two parties dominate the political scene of a country and both adopt similar economic and political agendas their tiny number grossly overstates the extent of political choice available to voters.

President Ronald Reagan was very popular and elected twice in large measure because voters wrongly credited his conservative neoclassical economic policies with solving the problem of stagflation, whereas stagflation actually ended due to the collapse of the oil price, as discussed previously. The other popular leader with a distinct right-wing agenda was Democratic president Bill Clinton; his neoclassical policies sustained the Thatcher-Reagan counter-revolution in the economic sphere; he oversaw the dismantling of market regulations and the abolition of Glass-Steagall, expediting the rise of the banking plutocracy to supreme power. Right-wing Republican president George W. Bush was a disciple of President Ronald Reagan; he did his best to further the counter-revolution economically, domestically, and internationally. Democratic president Barack Obama ran on a platform of change but his most significant policies supported the counter-revolution. The test came early, in 2008-2009. He proved his allegiance to the banking plutocracy by his massive rescue package of the big zombie banks without extending aid to the millions of troubled mortgage borrowers, as detailed in the section titled “The Economic Efficiency of Morality” in Chapter 1. Slogans aside, his policies have been essentially a continuation of those of the Bush presidency by, for example, not repealing the Bush tax cuts for the ultra-rich. Less obvious is the right-wing economic policy of Democratic President Jimmy Carter, who was the first president to adopt extremist neoclassical monetary policy, by not blocking the Fed’s violation of the interest rate ceiling set by Glass-Steagall—an action which culminated in the abolition of that law two decades later.

Worse than the limited choice, the political process in United States has ceased producing leaders with profound minds and a moral authority to match. The Republican Party has not produced a leader comparable to Eisenhower in six decades. Similarly, the Democratic Party has not produced anyone of the stature of Franklin Roosevelt or John F. Kennedy. The assassinations of President John Kennedy and his brother, Democratic presidential candidate Robert Kennedy, seem to have shut off the spigot for great American leadership. Perhaps those two assassinations signaled that henceforth the US presidency is a mortal career choice for real leaders. There have also been notable assassinations of popular centrist European political leaders who were against extreme rightwing policies such as former Italian Prime Minister Aldo Moro in 1978 and Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme in 1986.

After President Kennedy, American leaders, despite their memorable speech making, have stayed clear of implementing a moral and centrist agenda. Indeed, most presidential candidates for the 2016 election present themselves as supporters of extreme right-wing policies to get the backing of the mainstream media and Wall Street. For example, Hillary Clinton, the favorite Democratic presidential hopeful as of early 2016, is positioning herself to the right of the Republican Party by backing Wall Street and the policies of the neocons and the counter-revolution. She is supported by the big banks, the media empire, and big business. Her past decisions of backing wars on Iraq, Libya, and Syria indicate she is a female version of George W. Bush under a Democratic label. It also shows that the Democratic Party elders supporting her, including union leaders, are continuing with the counter-revolution agenda, which her husband, President Bill Clinton, instituted in the Democratic Party two decades ago.

Meanwhile, the political center, holding the vast majority of voters is ready for the taking by a leader with a moral and centrist economic vision. Senator Bernie Sanders, a Democratic candidate, is offering economic and democratic reforms as a Social Democrat in the European meaning of the term (i.e. a centrist in American terminology). However, his reform agenda has allied the deep pockets, the media empires, and the Democratic Party establishment against him despite his mass popularity, thereby reducing his chances as the Democratic Party candidate.

In the other camp, Donald Trump, the most popular Republican Party presidential candidate is also rejected by his party establishment because he is against certain core economic and foreign policies of the neocons and the counter-revolution.

The popularity of Sanders among the Democrats and Trump among the Republicans marks the continued transformation in American public opinion: a large segment of American voters now recognizes that the policies of the counter-revolution have served the interests of a microscopic minority of billionaires and sacrificed the interests of the vast majority of Americans. Indeed, President Obama owes his success to capitalizing on this change in public mood and used “change” as his campaign slogan to gain popular support, but he reneged on his promises once he was in the Whitehouse, by supporting the big banks instead of homeowners, pursuing neocon’s foreign policy, not repealing Bush’s tax cuts for the rich, and generally, implementing the counter-revolution. It also shows that Hillary Clinton, several Republican candidates, and the political establishments of both parties are out of touch with the mood of American voters. The establishments running both parties are relying on party delegates to rig primary elections and, therefore, the democratic process.

It would be misleading to leave the reader with the impression that the Republicans and Democrats are the only political parties in the United States. Indeed, there are approximately thirty other political parties, but, as of January 2015, not one was represented in the House of Representatives or the Senate.[298] To improve the democratic representation in both America and Great Britain, the present electoral system needs scrapping and replacing by proportional representation to permit the emergence of multi-party democracies. Indeed, as far back as the 19th century, John Stuart Mill, the last of the classical economists, advocated proportional representation to improve the standards of British democracy. Germany and Italy adopted proportional representation following World War II to prevent an autocratic concentration of political power in the hands of a single party and to curb their tendency for wars of aggression. For the same reasons, the overhaul of the obsolete and unfair voting systems in the United States and Great Britain would likely have the added benefit of putting an end to their wars of aggression.

The risk of not having a resilient multi-party political process in the lead countries of the West is that Western democracy will progressively degenerate into a parasitic capitalist version of the enfeebled Soviet Union in its final years. Yet reform in the shadow of the counter-revolution and the still rising power of the banking plutocracy has meagre chances. Granted that plutocracies desire to perpetuate and extend their economic and political powers, but the present path of Western plutocracies is leading to their demise and the economies they govern. Puzzlingly, they seem unaware of the economic, social, and political ills they are seeding. One possible explanation is that the aging Western plutocracies, are losing their mental prowess. Napoleon Bonaparte had observed that, “In politics stupidity is not a handicap,” nevertheless, extreme stupidity is.[299]

Voter participation reflects the public’s perception of the responsiveness of the democratic process to their needs. To protect its democracy, Switzerland made voting mandatory to ensure 100 percent participation. Where it is not mandatory, democracies must be on the alert to falling voter turnouts to take timely remedial actions. Low and falling voter participation suggests that a significant and growing proportion of the population thinks that their democracy is dysfunctional. In other words, they are disillusioned with and lost faith in the relevance and effectiveness of their democratic process.

The United States has been experiencing extremely low and falling voter participation. In the November 2014 midterm elections, voter participation fell to a record low of 36.4 percent, down from 40.9 percent in the 2010 midterm elections.[300] The democratic credentials of any country become doubtful if a majority of its voters no longer sees any utility in voting. In other words, about two thirds of US voters do not approve of the existing political arrangements; by boycotting elections, they are casting a negative vote on the entire democratic process as it stands. It also strongly suggests that the vast majority of Americans desire a centrist government, to the left of the current extreme right-wing agendas of the Republican and Democratic parties. To enhance voter participation, the political process must offer genuine political choice and adopt economic policies that serve the interests of the majority instead of the agendas of the ultra-rich.

Under capitalism, the two principal economic policy tools are fiscal and monetary policies. Moreover, under a capitalist democracy, these ought to be firmly under the control of the elected government and parliament (e.g., Congress). The US Federal Reserve, a private central bank, has declared itself “an independent central bank because its monetary policy decisions do not have to be approved by the President or anyone else in the executive or legislative branches of government.”[301] This is a clear statement that monetary policy is outside any democratic process. Moreover, Chapter 10 illustrated that in dollar terms the majority of US fiscal resources now fall under the control of the Federal Reserve, not Congress. The Federal Reserve has allotted trillions of dollars to various banks and corporations, both domestically and internationally, without congressional approval, which demonstrates that democratic fiscal control is slipping too. These fundamental violations of democracy have left Congress with partial control over fiscal policy only, while the bulk of economic policy decisions have passed to the hands of unelected bankers.

Political democracy is meaningless without economic democracy. Moreover, a high degree of economic inequality is typically a consequence of undemocratic and regressive tax and public expenditure policies, which promote increasing income and wealth disparity. For our purposes, we shall use wealth concentration as a proxy for economic inequality.

The great American leaders saw wars as theft and corruption.[302] The vast majority of Americans suffer multiple setbacks because of wars of aggression. First, such wars are crimes against humanity and result in needless deaths, permanent incapacities, and tragedies on both sides. Second, those wars divert resources away from much needed social services. Third, the bigger a war’s cost is, the bigger the opportunity for theft from American taxpayers. Fourth, American taxpayers are required to pay for these wars with interest added. Hence, President Dwight Eisenhower famously warned against wars of aggression, which only serve the interest of the military-industrial complex and not the public’s. Since World War II, America has waged too many wars, practically all without just cause. Accordingly, the frequency of wars of aggression indicates that self-interest is overwhelming societal-interest in public policy, symptomatic of a failing democracy.

Chapter 13 presented crime as a major negative economic and democratic externality.[303] Crime is also a barometer of social tension. A public policy that is insensitive to the needs of the majority is undemocratic, precipitating poverty and a high incidence of crime, whereas a compassionate policy improves the standard of living of the impoverished and curbs crime. History confirms this. Decades ago, when America was gentler, it was safer, and the social cost of crime was demonstrably less. Today, however, the United States has the largest prison population in the world, which suggests it has become less compassionate and less democratic.

Computing the Western Democratization Index

The democratic factors of the benchmark country are set to 100 percent, by definition; however, this does not imply a perfect score. For any one factor, the score of a country relative to the benchmark country can be less than or greater than 100 percent, depending on whether that country under study achieves lower or higher scores than the benchmark. The total score is arrived at by adding the score of individual factors, instead of multiplying them, to prevent a very low score in one factor from overwhelming the overall rating. For the same reason all six factors were given equal weight. The final democratic score is arrived at by totaling the score of the country under study and dividing it by 600 percent, the total score of the benchmark, to arrive at a standardized figure where the benchmark country has a total score of 100 percent.

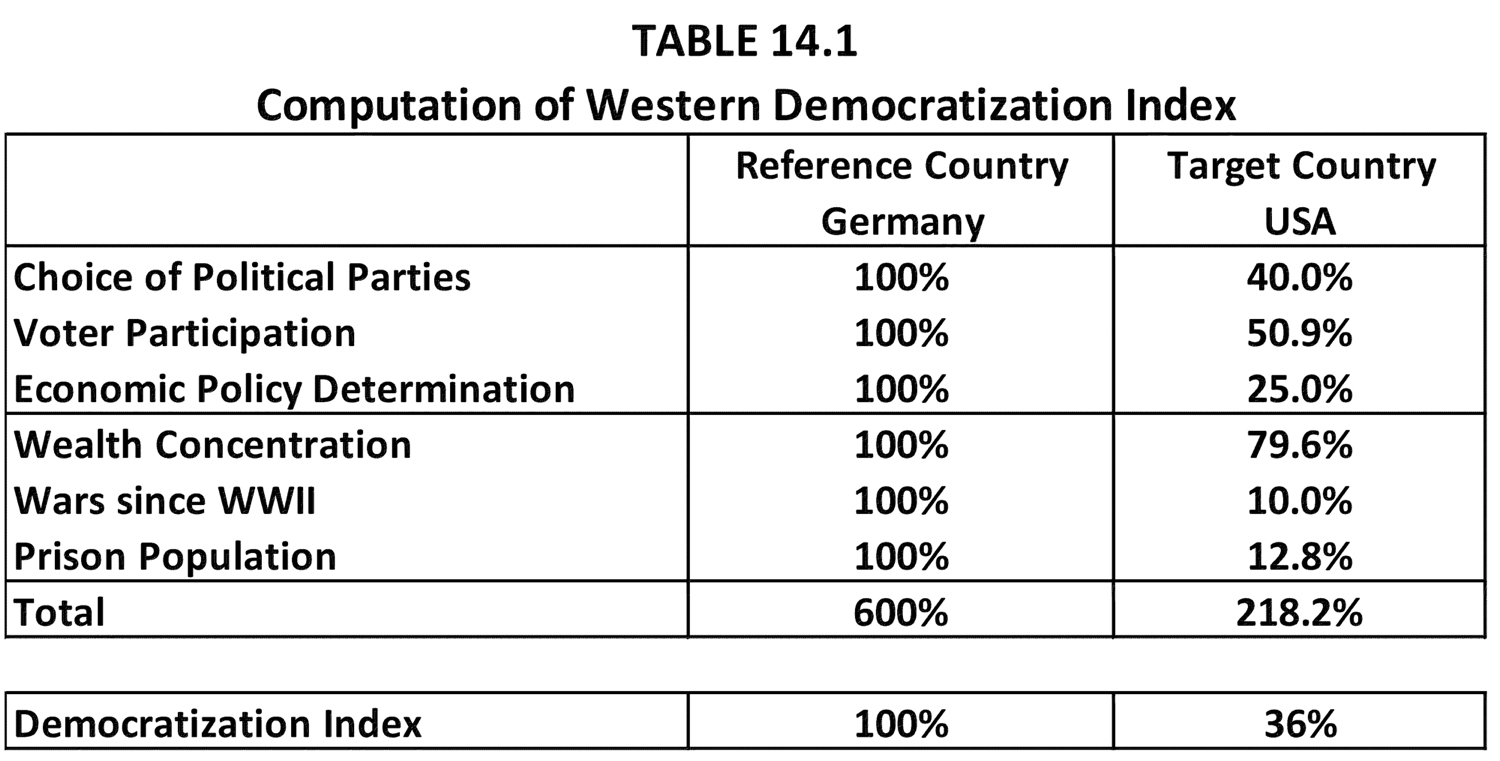

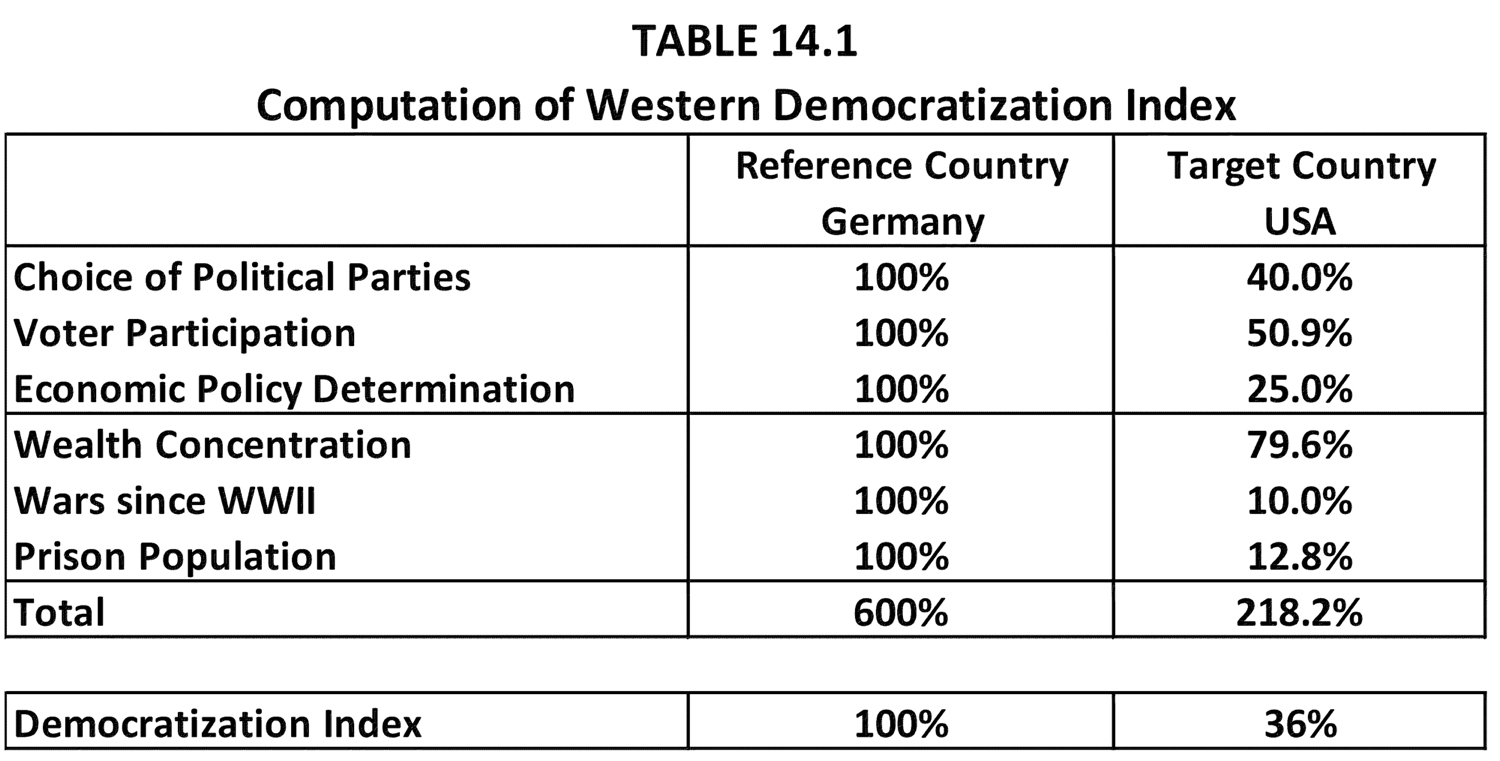

The following illustrates the computation of the Western Democratization Index:

1. Political Choice: Germany currently has five significant political parties represented in the German Federal Parliament (the Bundestag), while the United States only has two parties represented in the Congress.[304]

Accordingly, the score of the United States is: (2/5) = 40 percent.

2. Voter Participation: In Germany, 71.5 percent of the voters participated in the most recent election of the Bundestag, compared to 36.4 percent of American voters in the most recent congressional elections (in November 2014).

Therefore, the score of the United States is: (36.4/71.5) = 50.9 percent.

3. Economic Policy Determination: In the United States, a private central bank, the Federal Reserve, is in charge of the monetary policy; it has also appropriated massive fiscal powers without congressional approval. In contrast, the German central bank is publicly owned and controlled and elected officials approve all fiscal expenditure. Accordingly, the United States gets nil for a democratically determined monetary policy and only 1/2 for its fiscal policy, compared to 2 for Germany.

Hence, the US score is (0.5/2) = 25 percent.

4. Wealth Concentration: The richest 10 percent of the population in Germany and the United States owns 59.2 percent and 74.4 percent of all wealth, respectively.[305]

Thus, the score of the United States is (59.2/74.4) = 79.6 percent.

5. Wars of Aggression as Proxies for Corruption: Since World War II, the United States has been engaged in more than ten conflicts, while Germany has only participated in the War on Afghanistan at the insistence of the United States.[306]

Accordingly, the score of the United States is (1/10) = 10 percent.

6. Prison Population: Germany has 94 prisoners per 100,000 people, while the corresponding figure for the United States is 737 per 100,000.[307]

Therefore, the score of the United States is (94/737) = 12.8 percent.

Table 14.1 summarizes the scores of the United States relative to those of Germany, the benchmark country.

The fact that the overall Western Democratization Index rating of the United States is 36 percent (relative to Germany) shocked the author and may shock others too. It is still more shocking because German democracy itself has been waning, with the growing power of its own banking plutocracy. Stated simply, the United States has a serious democracy deficit.

The low democratic rating of the United States indicates that there is a clear need for reforming and improving American democracy as a prerequisite for improving American public sector efficiency. Improving democracy at home should take center stage, without the distraction of attempting to improve democracy in the rest of the world. In any case, it is vain for a country to try to instill in other countries what it lacks itself.

It would be interesting to know the scores of other Western democracies (e.g., Greece, Spain, Great Britain, France, Sweden, Switzerland), and those of emerging ones (e.g., Argentina, Brazil, India, Russia).

***

Parts III and IV identified several critical negative externalities. However, identifying a problem is only half the solution. Hence, the focus of Part V is finance and tax measures that can resolve or minimize the negative effects of said externalities.