At dawn on August 8, 1444, Infante Henrique—Prince Henry of Portugal, the Navigator—sat on horseback at the port of Lagos patiently awaiting the disembarkation of cargo that had arrived from Cape Blanco. Spectators assembled to witness the portentous ritual that was about to occur. People from town and countryside lined the streets and crowded together on boats, all hoping to catch sight of this sign of Portugal’s arrival as a world power. The day before this staged event, Lançarote de Freitas, the man who had led the very successful expedition in search of this cargo, had suggested to his lord, Prince Henry, that it be taken from the ship and herded to a suitable place for auction and distribution.

Lançarote’s suggestion pleased the Infante. The place of auction and distribution would be a field just outside the city gates. The early-morning unloading time, also suggested by Lançarote, would catch the cargo during a lull in their lament. His rationale for these suggestions arose from the source of the lament: “Because of the long time we have been at sea as well as for the great sorrow that you must consider they have at heart, at seeing themselves away from the land of their birth, and placed in captivity, without having any understanding of what their end is to be.”1 Carefully planned and perfectly executed, the disembarkation and movement from port to field, from hostile sea to Portuguese interior, had the effect Prince Henry desired. These actions announced boldly that under his leadership Portugal would stand beside the Muslims, Valencians, Catalans, and Genoese as peoples with power over black flesh. They now emerged as bearers of black gold, slave traders.2

This event did not mark the first time slaves had appeared at the port of Lagos. The newness of the event lay in the number of slaves, 235, in their place of origin, parts of Africa theretofore unvisited by the Portuguese, and, most important, in the ritual that surrounded their sale. This ritual was deeply Christian, Christian in ways that were obvious to those who looked on that day and in ways that are probably even more obvious to people today. Once the slaves arrived at the field, Prince Henry, following his deepest Christian instincts, ordered a tithe be given to God through the church. Two black boys were given, one to the principal church in Lagos and another to the Franciscan convent on Cape Saint Vincent. This act of praise and thanksgiving to God for allowing Portugal’s successful entrance into maritime power also served to justify the royal rhetoric by which Prince Henry claimed his motivation was the salvation of the soul of the heathen.3

The immediate focus in this story, however, is not the famed Prince Henry the Navigator, although he is a central actor and, as will become apparent later in this chapter, an incredibly important part of my concern. Nor is the immediate focus the African slaves, though they are the point of the matter. The immediate focus is the person who was charged to record, narrate, and interpret this ritual, Henry’s royal chronicler, Gomes Eanes de Azurara (or Zurara). It was Zurara who pronounced the moods and motivations of royalty. It was Zurara who set in texts the theological vision Prince Henry performed by his actions. Zurara did not share in Henry’s power, but he shared the stage with Henry, and in that sense he manifested his own power, the power of the storyteller. Zurara might be described accurately as a pre-Enlightenment historian, but that would be a soulless description. Zurara was a Christian intellectual at the dawn of the age of European colonialism, charged with offering the only real account of official history, a theological account.

At this time in the history of late medieval Christendom all accounts of events, royal or common, were theological accounts; that is, Christian accounts. Zurara, however, draws one’s attention precisely because of what begins to happen to theological vision and Christian voice at this moment in history. He was not an official theologian of the church. Born in the ever-widening echo of Thomas Aquinas’s thinking on the church and well before the epic-making theologians of Salamanca and Alcalá, Gomes Eanes (as he signed his name) did not rub shoulders with the keenest theological minds of the time, although he received enviable scholastic training. He was apprenticed to his predecessor as chronicler, Fernão Lopes, and given complete access to the library of the royal court, one of the strongest collections in Europe. There Zurara followed a Renaissance pattern of reading, both in scope and character. He read much—from Christian Scripture to theology to philosophy to astrology (science), from Aristotle to Dante to Averroes to Augustine, Aquinas, and Peter Lombard to medieval epics and romances. This serious intellectual work prepared him to assume the mantle laid down by Lopes.4

Zurara’s ascension to the position of royal chronicler implied no small secretarial post. In addition to being the chronicler, he was in charge of the royal library and all its records. He had also been appointed a commander in the elite military Order of Christ, in which the vows of celibacy, poverty, and obedience structured the ordered existence of nobles, knights, and squires, an order under the leadership of Prince Henry himself. Zurara writes as one seated next to power, and from that position he wrote the important accounts of the Navigator’s successes. His Chronicle of the Capture of Ceuta (1450) and his Chronicle of the Deeds of Arms Involved in the Conquest of Guinea (1457) remain crucial narratives of a founding moment in Christendom’s colonialism.5

Zurara narrates this ritual of slave capture and auction on August 8, 1444, in his Guinean chronicle, showing himself to be a royal chronicler in beautiful form, telling the story of Portugal’s rise by means of the chivalric genius of Prince Henry, the bravado of his loyal men, and the divine blessing of God. One could call this narrative royal religious ideology or pious propaganda, but by the time modern readers arrive at his account of this moment they see something different, even prophetic. As Zurara describes the event planned by Prince Henry and his assistant Lançarote, the triumphal coherence of his narrative starts to crack open. It is the only time in the entire chronicle that he set a chapter in a penitent prayer:

O, Thou heavenly Father—who with thy powerful hand, without alteration of thy divine essence, governest all the infinite company of thy Holy City, and controllest all the revolutions of higher worlds, divided into nine spheres, making the duration of ages long or short according as it pleaseth Thee—I pray Thee that my tears may not wrong my conscience; for it is not their religion but their humanity that maketh mine to weep in pity for their sufferings. And if the brute animals, with their bestial feelings, by a natural instinct understand the suffering of their own kind, what wouldst Thou have my human nature to do on seeing before my eyes that miserable company, and remembering that they too are of the generation of the sons of Adam?6

Zurara has not changed. This is still the story of Prince Henry. But at this moment the story of Portugal and its leader has been displaced by the suffering presence of these Africans. The power of Zurara’s description draws life from the pathos of these slaves. He invokes the idea of divine providence, of which he is a firm believer, and as he does so he locates a question that will from this time forward shadow this doctrinal theme: How should I understand the suffering of these Africans?7 Even when not speaking of Africans, every articulation of providence by colonial masters and their subjects will carry the echo of Zurara’s question. Zurara recognizes their humanity, their common ancestry with Adam. One should not, however, read moral disgust into his words. Zurara asks God in this prayer to grant him access to the divine design to help him interpret this clear sign of God-ordained Portuguese preeminence over black flesh. He seeks from God the kind of interpretation that would ease his conscience and make the event unfolding in front of him more morally palatable. His question seeds a problem of theodicy born out of the colonialist question bound to the colonialist project.

The irony that this question is posed in a Christian prayer that grasps the divine immutability must not go unnoticed. The idea of divine immutability anchors humans in the actions of a God who does not repent, change, or get caught by surprise but who works out without failure the divine will in space and time. That idea, even with the Scholastic incrustations of Zurara’s time, still carried the strong flavor of intimacy and trust in a God who is faithful and loving, even if mysterious. It makes sense that Zurara invokes it in the context of prayer. To do so exhibits his spiritual schooling in the Psalms, which show that the proper questioning of God should indeed take place inside prayer to God. Divine immutability rightly understood holds humans and their questioning of God inside knowledge of a loving and faithful God who hears their pained inquiries. The problem here is that Zurara will put divine immutability to strange new use. He employs providence, making it work at the slave auction. He then offers the famous account that has often been partially quoted:8

On the next day, which was the 8th of the month of August, very early in the morning, by reason of the heat, the seamen began to make ready their boats, and to take out those captives, and carry them on shore, as they were commanded. And these, placed all together in that field, were a marvelous sight; for amongst them were some white enough, fair to look upon, and well proportioned; others were less white like mulattoes; others again were as black as Ethiops [Ethiopians], and so ugly, both in features and in body, as almost to appear (to those who saw them) the images of a lower hemisphere. But what heart could be so hard as not to be pierced with piteous feeling to see that company? For some kept their heads low and their faces bathed in tears, looking one upon another; others stood groaning very dolorously, looking up to the height of heaven, fixing their eyes upon it, crying out loudly, as if asking help of the Father of Nature; others struck their faces with the palms of their hands, throwing themselves at full length upon the ground; others made their lamentations in the manner of a dirge, after the custom of their country. And though we could not understand the words of their language, the sound of it right well accorded with the measure of their sadness.9

Few places in the chronicle touch the intricacy of this account. Zurura slows the story down to give us sight of this suffering as well as to express a racial calculation. He goes through the differences in flesh and spirit, body and beauty that will become an abiding scale of existence:

But to increase their sufferings still more, there now arrived those who had charge of the division of the captives, and who began to separate one from another, in order to make an equal partition of the fifths; and then was it needful to part fathers from sons, husbands from wives, brothers from brothers. No respect was shown either to friends or relations, but each fell where his lot took him. O powerful fortune, that with thy wheels doest and undoest, compassing the matters of this world as pleaseth thee, do thou at least put before the eyes of that miserable race some understanding of matters to come; that they may receive some consolation in the midst of their great sorrow. And you who are so busy in making that division of the captives, look with pity upon so much misery; and see how they cling one to the other, so that you can hardly separate them. And who could finish that partition without very great toil? For as often as they had placed them in one part the sons, seeing their fathers in another, rose with great energy and rushed over to them; the mothers clasped their other children in their arms, and threw themselves flat on the ground with them; receiving blows with little pity for their own flesh, if only they might not be torn from them. And so troublously they finished the partition.10

Zurara ends this chapter and this important episode in the chronicle with Prince Henry bringing a holy coherence to the whole matter:

The Infante was there, mounted upon a powerful steed, and accompanied by his retinue, making distribution of his favours, as a man who sought to gain but small treasure from his share; for of the forty-six souls that fell to him as his fifth, he made a very speedy partition of these for his chief riches lay in his purpose; for he reflected with great pleasure upon the salvation of those souls that before were lost. And certainly his expectation was not in vain; for, as we said before, as soon as they understood our language they turned Christians with very little ado; and I who put together this history into this volume, saw in the town of Lagos boys and girls (the children and grandchildren of those first captives, born in this land) as good and true Christians as if they had directly descended, from the beginnings of the dispensation of Christ, from those who were first baptized.11

Zurara deploys a rhetorical strategy of containment, holding slave suffering inside a Christian story that will be recycled by countless theologians and intellectuals of every colonialist nation. The telos and the denouement of the event will be enacted as an order of salvation, an ordo salutis—African captivity leads to African salvation and to black bodies that show the disciplining power of the faith. Zurara clearly intends the text to be read in this way. But his narrative inadvertently exposes a deeper point of coherence that betrays his idealized vision of Prince Henry. That point of coherence counteracts his placement of the Infante and his actions as the point of salvific coherence. The deeper point of coherence is the suffering Christ image, the paradigmatic image of suffering carried in the body of Jesus of Nazareth. Zurara’s rhetoric moves inexplicably near biblical allusions and accounts of Jesus’ suffering: “Therefore, to consecrate the people by his own blood, Jesus also suffered outside the gate. Let us then go to him outside the camp, bearing the stigma that he bore” (Hebrews 13:12–13 NEB).

Zurara wrote a passion narrative, one that reads the gestures of slave suffering inside the suffering of the Christ.12 The christological architecture his words fall into is inescapable, words tracing out the actual frame of Jesus’ own march of suffering, separation, and death. Both Jesus and the slaves suffer outside the city gates. Outside the city gate for Jesus meant suffering in a place designated by the Roman state for displaying its considerable power over bodies. The parallel with the slaves is remarkable. They too stand outside the city gates and mark the orchestration of the Portuguese state over their lives. This christological architecture of the sale of slaves like the Christ event signifies a similar instrumentality, a similar use of the body for the sake of the state. As Zurara articulates the exercise of church and state power over bodies he echoes some of the deepest realities of Jesus’ agony and in effect triggers misapprehension and reversal similar to those found in the condemnation of Jesus. The innocent suffer the penalty of the guilty. Like Jesus, these peoples of distant lands are brought to a place where a crucifying identity, slave identity, will be forever fastened like a cross to their bodies: “They brought Jesus to the place called Golgotha, which means ‘Place of a Skull,’ and they offered him drugged wine, but he did not take it. Then they fastened him to the cross” (Mark 15:22–24a NEB).

The crucifixion portrays Christ’s powerlessness, a powerlessness shared by the chronicler, who is helpless to do anything other than remember the scene and tell the story. Zurara places himself in his story in the position of one who watches helplessly as horror unfolds. His position in the chronicle does not align with the positions of Pilate and the women who wept at the suffering of Jesus of Nazareth. Zurara takes a position like that of the writers of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, who recall Jesus’ torture-induced agony. His language here does not claim a connection between the two agonies, of slave and savior. But his language cannot prevent it. Jesus prostrated on the ground at Gethsemane and contorted on the cross personifies tribulation through his groans, tears, and loud cries, his eyes steadfastly on heaven seeking paternal consolation. In comparison, slave flesh throws itself to the ground, groans, fixes its eyes on heaven, and cries loudly, “as if asking help of the Father of Nature.” Holy body and slave body act the same, but Zurara will not allow himself to see a Jesus-like cry of dereliction in the slaves’ cries. That would be to see too much. The Father of Nature will not be fully identified with the Father of Jesus Christ. But Zurara comes close to it. He joins two forms of indecipherability, the screams of Jesus and the screams of the slaves. The words of the slaves expose a chasm between perception and right interpretation. In like manner the following passage from Mark’s gospel shows Christ’s words being misunderstood. Those pitiful words mark for the hearers their inability to join perceived pain to true interpretation: “At midday a darkness fell over the whole land, which lasted till three in the afternoon; and at three Jesus cried aloud, ‘Eloï, Eloï, lema sabachthani?’ which means ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’ Hearing this, some of the bystanders said, ‘Listen! He is calling Elijah.’ Then Jesus gave a loud cry and died” (Mark 15:33–34, 37 NEB).”

While the listeners in this passage misinterpret Christ’s words Mark does not. Yet in Zurara’s narrative neither listener nor writer can translate the words uttered by this soon-to-be chattel. The action of church and state power, however, was not thwarted by linguistic boundaries. The languages of the newly formed slaves required no hope of a Pentecostal miracle, no need to pray for interpretation, because the imperial reflex on display captured strange tongues and drowned them in the familiar sound of Portuguese. Indeed, one may discern an evil prophecy created and soon to be fulfilled in this burial of native tongues beneath the loud sound of Portuguese: The languages of the enslaved will be bound to the languages of the Europeans, as peasant to royalty, as the lesser to the greater. Unknown tongues will be overcome not by a surprising linguistic act of God, but by the energies of market and nation-state.

Another crucial parallel between these two narratives is the central role of death. Christ takes on death to overcome it, while slaves are bound to death by being killed and through its use as a threat in order to subdue them. This is a reversal of the reversal, a christological deformation. That is, the body of Jesus will ultimately indicate the victory of God over death, but in this horrific scene the African’s body indicates the ultimate victory of death. The holy use of Jesus’ body—the one who became a slave to die as a sinner for humankind—parallels the separation of slaves into lots for Portuguese servitude. Echoing the merciless beating of Jesus, mothers are beaten, Zurara observes, “with little pity for their own flesh,” as they cling hopelessly to their children, attempting to prevent the tearing away. At the end, all that remains is the dividing of the slaves into equal lots, just as all that was left was the dividing of the Savior’s garments. What Mark writes, “They shared out his clothes, casting lots to decide what each should have,” reveals the telos of the captured body, consumption (Mark 15:24b NEB).

Prince Henry emerges from this segment of the chronicle as the stabilizing focal point, moving the reader out of the chaos of this first auction. His powerful presence overcomes the screams, cries, beatings, and noise of the captives as well as the horrified cries of some of the onlookers. He will lead them into the light of salvation for untold generations. Yet Zurara gave too much in this story. It will not all fit easily into the account. From this point forward this account haunts his constant justification of the slave trade—we, the Portuguese, will save them. They will become Christians. Yet inadvertently, in telling the story of Portugal’s rise, Zurara joins the slave body to the body of Jesus. He would not have done this on purpose, as he seems unaware of the immense tragedy of the moment he has entered. But Zurara also reveals he is not innocent. He knows—behold the man! Zurara prays, he cries, he speaks to those who do the dirty work of mutilating the black body.

The christological pattern of his narrative illumines the cosmic horror of this moment and also helps the reader recognize the unfolding of a catastrophic theological tragedy. Long before one would give this event a sterile, lifeless label such as “one of the beginning moments of the Atlantic slave trade,” something more urgent and more life altering is taking place in the Christian world, namely, the auctioning of bodies without regard to any form of human connection. This act is carried out inside Christian society, as part of the communitas fidelium. This auction will draw ritual power from Christianity itself while mangling the narratives it evokes, establishing a distorted pattern of displacement.

Christianity will assimilate this pattern of displacement. Not just slave bodies, but displaced slave bodies, will come to represent a natural state. From this position they will be relocated into Christian identity. The backdrop of their existence will be, from this moment forward, the market. Zurara narrates this horror of displacement within a strange new soteriological orientation. Divine immutability yields Christian character—an unchanging God wills to create Christians out of slaves and slaves out of those black bodies that will someday, the Portuguese hope, claim to be Christian.

Slave society was not the new reality appearing here. Zurara understood enough Scripture, Christian tradition, and ecclesial and state polities to articulate a hermeneutics of forced servitude. The new creation here begins with Zurara’s simple articulation of racial difference: “And these, placed all together in that field, were a marvelous sight; for amongst them were some white enough, fair to look upon, and well proportioned; others were less white like mulattoes; others again were as black as Ethiops [Ethiopians], and so ugly, both in features and in body, as almost to appear (to those who saw them) the images of a lower hemisphere.”13 Through comparison, he describes aesthetically and thereby fundamentally identifies his subjects. There are those who are almost white—fair to look upon and well-proportioned; there are those who are in between—almost white like mulattoes; and there are those who are as black as Ethiopians, whose existence is deformed. Their existence suggests bodies come from the farthest reaches of hell itself.14 Zurara invokes, in this passage, a scale of existence, with white at one end and black at the other end and all others placed in between.

This is not the first time the words white and black indicate something like identity. Their anthropological use in the Iberian and North African regions has an episodic history that extends well before Zurara’s utterances.15 Zurara, however, exhibits an aesthetic that is growing in power and reach as the Portuguese and Spanish begin to join the world they imagined with the world they encounter through travel and discovery. In the fourteenth-century geographical novel The Book of Knowledge of All Kingdoms (also known as The Book of Knowledge), these two worlds, the imaginary and the real, are joined.16 It is fundamentally a Christian text, beginning with its invocation of the triune identity of God in proper orthodox form. At the beginning of the book the author situates his own history within multiple accounts of time—Jewish, Christian, pagan, Muslim—in a way that could, with appropriate qualifications, be seen as quite culturally generous, if not downright pluralist. This work, known to Prince Henry and Zurara, does not offer a straightforwardly derogatory view of black flesh.17 Rather its comparison is subtle. Black is the result of environmental harm. Such harmed flesh, burnt flesh is not present among whites.

The author, in recounting his travels to different places, notes several times that the people are black, or black as pitch. They are Christian, yet they are black. As the author draws near the land of Prester John, the priest-king believed to govern a holy realm and a great army of African warriors, he again notes the people’s particulars: “But they are as black as pitch and they burn themselves with fire on their foreheads with the sign of the cross in recognition of their baptism. And although these people are black, they are men of good understanding and good mind.”18 Christian and black are juxtaposed—the one overcoming the other. The land is hot but Christian, so the people are black yet in a condition of grace. This graced but harmed condition of black bodies stands in stark contrast to the bodies of those from the land the author describes as India. That land is equally hot as the land of the blacks, but the towns are close to the sea, and the moist air tempers the heat. The result is a different body: “And in this way they derived beautiful bodies and elegant forms and fine hair, and the heat does nothing else to them except make them brown in color.”19 Few of Zurara’s or Prince Henry’s contemporaries seemed to question the veracity of the author’s accounts of people, places, and routes. Prince Henry in fact considers The Book of Knowledge one of his indispensable guides as he envisions further conquest of Africa. These accounts faltered as Iberian travelers pressed the real world against this imaginary one. Yet land and body are connected at the intersection of European imagination and expansion. The imagined geography diminished in strength as a more authentic and accurate geography emerged. The scale of existence, however, with white (unharmed) flesh at one end and black (harmed) flesh at the other, grew in power precisely in the space created by Portuguese expansion into new lands.

The often-used term European expansion fails to capture the spatial disruption taking place at this moment, a moment beautifully captured by Zurara. This Portuguese chronicler is watching and participating in the reconfiguration of space and bodies, land and identity. This is the newness present in Zurara’s simple observation. Again, land and body are connected at the intersection of European imagination and expansion, but what must be underscored is the point of connection—the Portuguese and the Spanish, that is, the European. He is the point of connection. He stands now between bodies and land, and he adjudicates, identifies, determines. The position of the agent is equal in importance to the actions. Zurara is capturing the twin operations of discovery and consumption. With those twin operations, four things are happening at the same time: first, people are being seized (stolen); second, land is being seized (stolen); third, people are being stripped from their space, their place; and fourth, Europeans are describing themselves and these Africans at the same time. There is a density of effects at work here far beyond a notion of expansion.

In this chapter I register that density of effects, especially as it relates to the formation of human identity in modernity.20 Centrally, I register the effects of the reconfiguration of bodies and space as a theological operation. That theological operation, heretical in nature, binds spatial displacement to the formation of an abiding scale of existence.

The ordering of existence from white to black signifies much more than the beginnings of racial formation on a global scale: it is an architecture that signals displacement. Herein lies the deepest theological problem. Zurara brings into view the crossing of a threshold into a distorting vision of creation. This distorting vision of creation will lodge itself deeply in Christian thought, damaging doctrinal trajectories. My use of the word distortion does not imply a prior coherent, healthy, and happy vision of creation that will be lost in the age of discovery. The newness of the world was unanticipated by all. That newness coupled with European power, greed-filled ambition, and discursive priority drew distorting form out of Christian theology.

The royal chronicler’s account of the slave auction, intended to immortalize the exploits of the Navigator, collapses into the crucifixion narrative in which the Son is subjected to evil powers. In Zurara’s narrative, these evil powers find their parallel in Prince Henry, who, of course, would never have understood himself as such.21 Instead, the Infante understood himself and Zurara described him as the good son sent for the sake of the nation. In his Chronicle of the Capture of Ceuta Zurara masterfully ascribes to the prince the trappings of anointed sonship. His mother, Queen Philippa, is described in theotokos-like ways. Her deathbed imperial oration to her sons, especially to Henry, prophesies and commands him to lead the elite of the nation to the glory that is their due. This holy beginning of his reign is further established by the appearance of the Virgin Mary next to Philippa as she lay dying. On her deathbed Philippa contemplates the divine, transfigured in the Holy Virgin’s presence.22 The religious reality of Prince Henry approximates that of the chronicle. A very pious and theologically astute man, he was known to quote Scripture to strengthen his arguments and had even considered taking religious vows. In his latter years, he established a chair of theology at Lisbon University and had at hand when he died a copy of Peter Lombard’s Libri sententiarum quatuor.

Henry thus dually represents Christ and Christ’s executioners. This contradiction is made possible by a Christianity contorting through travel and discovery. Zurara’s aesthetic judgments move with the Iberian and other colonial empires, refine through contact with other peoples, and merge into what will come to be believed as obvious. Slowly, out of these actions, whiteness emerges, not simply as a marker of the European but as the rarely spoken but always understood organizing conceptual frame. And blackness appears as the fundamental tool of that organizing conceptuality. Black bodies are the ever-visible counterweight of a usually invisible white identity. My use of the term scale should not be conflated with what will later develop as racial hierarchy, intellectual, cultural, or religious, although there are present at this time profoundly hierarchical elements. The explanatory power of the notion of racial hierarchy does not capture the density of the operation of this scale. Scale here refers to the possibility realized from the legacy of Prince Henry onward of seeing and touching multiple peoples and their lands at once and thinking them together. This process will be theological.

The process is theological because it is ecclesial. This kind of comparative thinking was not simply the child of burgeoning colonial nation-states. Church and state, popes and kings and queens enfold each other in bringing forth new ways of interfacing with their world. This is truly an inter-course. However, in this joining the church establishes the framework within which the nations will interpret not only their statecraft but also the peoples they encounter through exploration and conquest. In his bull Romanus Pontifex of January 8, 1455, Pope Nicholas V displays the power of ecclesial dictum by summarily awarding regions of the known world to Portugal. This papal power over space, which will be exercised repeatedly, rested on an abiding christological and ecclesiological principle—that the church exists for the sake of the world. It is the fount of salvation, and the pope, servant of the servants of God, for the sake of Christ and through Christ, lays claim to the entire world. Romanus Pontifex rehearses this central power of Christ’s successor:

The Roman pontiff, successor of the key-bearer of the heavenly kingdom and vicar of Jesus Christ, contemplating with a father’s mind all the several climes of the world and the characteristics of all the nations dwelling in them and seeking and desiring the salvation of all, wholesomely ordains and disposes upon careful deliberation those things which he sees will be agreeable to the Divine Majesty and by which he may bring the sheep entrusted to him by God into the single divine fold, and may acquire for them the reward of eternal felicity, and obtain pardon for their souls. This we believe will more certainly come to pass, through the aid of the Lord, if we bestow suitable favors and special graces on those Catholic kings and princes, who like athletes and intrepid champions of the Christian faith … not only restrain the savage excesses of the Saracens and of other infidels, enemies of the Christian name, but also for the defense and increase of the faith vanquish them and their kingdoms and habitations.23

The contemplation of the Vicar of Jesus Christ is a beautifully sublime and incredibly powerful action described here. It captures the central soteriological action of the church; seeking and desiring the salvation of all peoples. The position of the church in relation to the nations echoes the original constituting relation, that between Israel and the world. Here Israel has been superseded and the framework reconstituted through the Vicar of Christ so that the whole world is viewed through boundless desire. This presents the deepest theological problem and the greatest theological possibility. This boundary-less desire is to “bring the sheep entrusted to him by God into the single divine fold,” presenting a totalizing vision that activates a thoroughgoing antiessentialist rendering of peoples. Through this rendering all peoples become simply sheep bound under paternalecclesial care.

This salvific concern is at the heart of the Christian gospel, its radicalism breathtaking, but, placed by the pope in the hands of those whom the pope called the “athletes and intrepid champions of the Christian faith,” it becomes a different kind of radicalism. This radical concern becomes, through the pope’s own official narration, embodied in the energy, efforts, and exploits of Prince Henry:

And so it came to pass that when a number of ships of this kind [caravels] had explored and taken possession of very many harbors, islands, and seas, they at length came to the province of Guinea, and having taken possession of some islands and harbors and the sea adjacent to that province, sailing farther they came to the mouth of a certain great river commonly supposed to be the Nile, and war was waged for some years against the people of those parts in the name of the said King Alfonso and of the infante; and in it very many islands in that neighborhood were subdued and peacefully possessed, as they are still possessed together with the adjacent sea. Thence also many Guineamen and other negroes, taken by force, and some by barter of unprohibited articles, or by other lawful contracts of purchase, have been sent to the said kingdoms. A large number of these have been converted to the Catholic faith, and it is hoped by the help of divine mercy, that if such progress be continued with them, either those peoples will be converted to the faith or at least the souls of many of them will be gained for Christ.24

It would be a mistake to conclude that Prince Henry’s commercial interests are hidden inside the pope’s theological interests. Both concerns are joined and in the open. Indeed, it is precisely the joining of these concerns, commercial and theological, that enables the translation of soteriological radicalism into a racial radicalism. As the pope narrates Henry’s holy exploits, including the taking of “many Guineamen and other negroes,” a large number of whom, he notes, have been converted to the Catholic faith, he inscribes a new reality for black flesh. He never mentions their tribal, linguistic, or geographic specifics; these aspects of their identities are rendered irrelevant.25

Nicholas V’s description is a superficial reading of human communities that ignores their intimately particular characteristics, a descriptive practice that will be used by many explorers and priests. Yet one should not simply excuse this description as naïve anthropology or harmless generalization. Nicholas V offers insight into the power of a theological account of peoples that draws life from the doctrine of creatio ex nihilo, the creation by the Creator of all things out of nothing.

Envisioning the world as created out of nothing yields two bedrock hermeneutical principles. First, there is a fundamental instability to all things. Nothing is sure in itself. All things are contingent and held together by God. Rather than rendered through a godlike stability, the world ex nihilo means that all things carry inherent possibilities of continuity or discontinuity. Indeed, the fragility of human existence marks humans’ inherent instability.

When viewed through this hermeneutical horizon, peoples exist without a necessary permanence either of place or of identity. This kind of antiessentialist vision facilitates a different way of viewing human communities. The essential characteristic of people is their need—for pardon and life, that is, for salvation from God. Nicholas V notes in hope that people may “acquire … the reward of eternal felicity, and obtain pardon for their souls.”26

The second hermeneutical principle is the identity of the Creator. Christ is the creator of all things. Locating the Creator in space and time establishes the most important aspect of the incarnation. God has come and fully entered the reality of the creation. In space and time, into the instability of the world came a new point of stability and life. Equally important is the arche, the beginning. Jesus Christ is the beginning of all things. All things belong to him as text to author. The doctrine of divine enfleshment yields both the idea of divine ownership and that of salvation embodied in the here and now. This special sense of embodiment undergirds Nicholas V’s sense of geographic authority over all peoples and all lands. God in Christ allows humans to participate in his life, and within that participation there exists a transferability of his authority to humans. As the central point of transferability, the representative of Christ, Nicholas V, may delegate Prince Henry and his cohort to act on his behalf. It is precisely this point of delegation that establishes a trajectory reaching from Henry through the pope back to the incarnation itself—a trajectory of ownership and salvation. Nicholas V states that the Infante from his youth geared his entire life to “cause the most glorious name of the … Creator to be published, extolled, and revered throughout the whole world, even in the most remote and undiscovered places.”27

I have not entered fully into the intricacies of a Christian doctrine of creation or the doctrine of the incarnation. However, the use of those doctrinal logics can be seen working to frame the concepts that will enable the thinking of peoples together with regard to race. These doctrinal logics help one understand the oft-quoted and equally theologically underinterpreted papal permission given to King Alfonso and Prince Henry:

To invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue all Saracens and pagans whatsoever, and other enemies of Christ wheresoever placed, and the kingdoms, dukedoms, principalities, dominions, possessions, and all movable and immovable goods whatsoever held and possessed by them and to reduce their persons to perpetual slavery, and to apply and appropriate to himself and his successors the kingdoms, dukedoms, counties, principalities, dominions, possessions, and goods, and to convert them to his and their use and profit … the said King Alfonso or by his authority, the aforesaid infante, justly and lawfully has acquired and possessed, and doth possess, these islands, lands, harbors, seas, and they do of right belong and pertain to the said King Alfonso and his successors.28

Repeating in part the permissions given in Dum diversas, his bull of June 18, 1452, Nicholas V granted this request of King Alfonso in light of the ongoing military struggle against Islam.29 But there is more at work here than the vicissitudes of church-statecraft. The pope granted Portuguese royalty the right to reshape the discovered landscapes, their peoples and their places, as they wished. These actions inscribe the contingency of creation itself within the will and desire of church and the colonial powers. The inherent instability of creation means that all things may be altered in order to bring them to proper order toward saved existence. Church and realm, represented in this moment by Nicholas V and Prince Henry (and King Alfonso), stand between peoples and lands and determine a new relationship between them, dislodging particular identities from particular places. Through a soteriological vision, church and realm discern all peoples to exist on the horizon of theological identities.

Displacement is the central operation at work here. The subtleties of its operation move in two directions, both of which one must see in order to understand the depth of this theological mistake. One direction is detectable from the early moments of New World discoveries. Consider the words of Christopher Columbus from the account of his third voyage to the New World. He has dropped anchor at the southeastern tip of Venezuela, near Trinidad, a place he named Punta del Arenal: “The next day there came from the east a large canoe with 24 men in it, all of them young and bearing many weapons…. As I said, they were all young and fine looking and not negroes but rather the whitest of all those that I had seen in the Indies, and they were graceful and had fine bodies and long, smooth hair cut in the Castilian manner.”30 This is simply a description intended to help Ferdinand and Isabella grasp the details of Spain’s New World, especially the lucrative new find of a continent. But it is also a down payment on things to come. The logic of Columbus’s description is obvious—the comparison begins with the known, the self. Thus the whiteness he names is reflective, even reflexive of their European bodies—graceful, fine, with long, smooth hair, even cut like theirs. Rotem Kowner writes that for European explorers at this time “the color white, did not carry explicit racial connotations but signified culture, refinement, and a ‘just like us’ designation.”31 However, its origins or originators are not what make this point of comparison critical for us.

The power of Columbus’s description lies in its comparative range. It connects the bodies of the new land (Africa) to the bodies of the other new land (the Americas), through the exercise of an aesthetic with breathtaking geographic flexibility. The aesthetic is of the land but not of the land, of the people but not of the people. It is of the land and the people in the sense that Columbus, like his intellectual predecessors, speculates that specific environs cause the specific characteristics of people. It is not of land and people because these specific characteristics become a racial transcendental, present among completely different peoples with supposedly similar climates. Again, as Columbus reflected on his discovery of a new continent and offered his famous observation that the earth is pear-shaped or like a “woman’s nipple on a round ball,” he substantiates his hemispheric theory by drawing on this aesthetic: “I find myself 20 degrees north of the equinoctial line, right of Arguin and those lands, where the men are black and the land very burnt. And when I went to the Cape Verde Islands I discovered that the people there are much darker, and the farther south one goes the more extreme their color becomes so that, at the same latitude on which I was, namely, that of Sierra Leone, where the North Star at nightfall was five degrees above the horizon, the negroes are the blackest.”32 Columbus, however, believes that, given the true shape of the earth, conditions at the island of Trinidad and the land of Gracia (his name for modern-day Venezuela) create a different result in people: “I found the mildest temperatures and lands and trees as green and beautiful as the orchards of Valencia in April, and the people there have beautiful bodies and are whiter than the others I was able to see in the Indies and have very long and smooth hair; they have greater ingenuity, show more intelligence, and are not cowardly.”33 Columbus with great precision exhibits the power of the racial scale. One sees that power in its mobility and its flexibility. It is of the world but not of any specific world. It is tied to specific flesh, but it also joins all flesh. Such identity markers do not establish racial essences as their first work. They quietly, beneath the surface, join human beings and in effect uncouple their identities from specific places. Yet the first point of uncoupling is the European himself. Consider the famous statement of Garcia de Escalante Alvarado (1548), the Spaniard who provided the first actual account of Japan and the Japanese: “It is a very cold country…. The inhabitants of these islands are good-looking, white, and bearded, with shaved heads…. They read and write in the same manner as do the Chinese; their language is similar to German…. The superior classes are dressed in silk, brocade, satin, and taffeta; the women have mostly very white complexions and are very beautiful; they are dressed in the same manner as the women of Castile.”34 His vision of the Japanese draws them into a reality that is physical yet without spatial boundary, a reality signaled by whiteness. Escalante and his compatriots are by no means singular in this operation. As all the European empires draw on the flexibility of the racial scale, they pull themselves into this boundary-less reality. This is nothing less than a theological operation. Like the designations of sinner and saint, convert and heretic, believer and unbeliever, faithful and apostate, this linguistic deployment alters reality, blowing by and through the specifics of identity bound to land, space, and place and narrating a new world that binds bodies to unrelenting aesthetic judgments. The European himself is the key to this theological act of displacement. It is not incidental that Columbus, like so many who follow in his footsteps, envisions a soteriological motive for his exploration and colonialism: “The Holy Trinity inspired Your Highnesses to undertake this enterprise of the Indies and through His infinite goodness made me His envoy on account of which I came with this plan into your royal presence, you being the most noble Christian princes toiling for the faith and its propagation.”35 The gospel is always embodied in the acts of faithful Christians, and yet the gospel is without constrictors of space. It is quintessentially movable, elastically stable over vastly different locations. The age of discovery entails that the European body will take on these exact characteristics. But not simply the European body but also, equally important, the African body will take on similar characteristics. These body differences will be articulated through white and black in such a powerful way that their similitude will extend to all peoples. These bodies, black and white, become almost spectral, more precisely, conceptually able to be superimposed over all other bodies. These bodies become visible and invisible in different ways with different purposes. That performed visibility and invisibility shows itself in the constant turnings and evolutions of comparative thinking.

The brilliant Jesuit Alessandro Valignano (1539–1606) shows this incredible ability to capture all flesh within the logic of white and black existence. Born of an elite Neapolitan family and quickly moved through the Jesuit ordination process and ranks, he arrived as vicar-general and visitor to Japan in 1579. In his famous Sumario of 1580 he offers his studied reflections on the Japanese and the viability of the mission to Japan: “These people are all white, courteous and highly civilized, so much so that they surpass all the other known races of the world. They are naturally very intelligent, although they have no knowledge of sciences, because they are the most warlike and bellicose race yet discovered on the earth.”36 Later on in the Sumario one of his points of comparison appears: here he reflects on the superiority of Japanese conversion based on their supposed racial difference:

There is this difference between the Indian and Japanese Christians, which in itself proves that there is really no room for comparison between them, for each one of the former was converted from some individual ulterior motive, and since they are blacks, and of small sense, they are subsequently very difficult to improve and turn into good Christians; whereas the Japanese usually become converted, not on some whimsical individual ulterior move (since it is their suzerains who expect to benefit thereby and not they themselves) but only in obedience to their lord’s command; and since they are white and of good understanding and behavior, and greatly given to outward show, they readily frequent the churches and sermons, and when they are instructed they become very good Christians.37

Valignano’s use of black in this derogatory fashion was not unusual. As the historian C. R. Boxer noted, it was not at all strange to hear the Indians, Chinese, or even Japanese referred to as “niggers.” Francisco Cabral, the Portuguese superior of the mission to Japan (1570-81) who resisted developing an indigenous clergy, stated that “the Japanese are Niggers and their customs barbarous.”38 In order to understand the elastic power of the term black in its derogatory form one must remember the nature of the comparative thinking that is in operation.

Because Valignano’s concern as vicar-general and visitor was to evaluate the possibilities of an authentic Christian existence and identity in the new lands—Africa, India, China, and Japan—his comparative analysis was driven by a deeply ecclesial concern. The concern was whether the performance of Christian practices was rooted in a saving effect in the individual or was merely a façade covering disingenuous behavior or impenetrable ignorance. The questions at stake were not only who could become a true Christian, but also who might ascend the heights of Christian identity and become a lay leader, priest, or even possibly a Jesuit brother. Valignano understood himself to be engaged in nothing less than an act of spiritual discernment.

What informed Valignano’s powerful spiritual discernment of the salvific possibilities of alien flesh was the presence of the most decisive and central theological distortion that exists in the church, a distortion that was growing in power and extension with each new generation. That distortion was the replacement of Israel, or, in its proper theological term, supersessionism. Crudely put, in supersessionist thinking the church replaces Israel in the mind and heart of God. It will take my entire treatment, each chapter adding layers to my account of this decisive distortion, to describe the awesome effects of this way of thinking on the imagination of Christians. At this point one can begin to glimpse the supersessionist effect in Valignano’s comparative thinking. This effect begins with positioning Christian identity fully within European (white) identity and fully outside the identities of Jews and Muslims. The space between these identities, Christian on the one side and Jews and Muslims on the other, became the space within which one could discern authentic conversion. This discernment constituted an ecclesial logic applicable to the evaluation of all peoples.

The comparative work built from this ecclesial logic and its most important precedent. In the medieval Iberian world two groups of Christians were already seen as deeply suspect in regard to the veracity of their Christian identity: moriscos (converted Muslims or Christian Moors) and conversos (converted Jews or New Christians), sometimes referred to with the derogatory term marranos (meaning swine in Spanish). It did not matter whether the conversion of Jew or Muslim was forced or chosen; their Christian identity was troubled. It was a dangerous Christian identity owing to the possibility of their return to Judaism or Islam. There was also the frightening possibility that they might be secretly practicing Jews or Muslims, lodged deep in the Christian body. This fear and suspicion had an Augustinian-like multigenerational effect so that anyone with Jewish or Moorish “blood” must be ferreted out and barred from leadership in the church.39

Such suspicion and fear, though common in Christian Spain and Portugal as well as in other parts of medieval Europe, indicated a profound theological distortion. Here was a process of discerning Christian identity that, because it had jettisoned Israel from its calculus of the formation of Christian life, created a conceptual vacuum that was filled by the European. But not simply qua European; rather the very process of becoming Christian took on new ontic markers. Those markers of being were aesthetic and racial. This was not a straightforward matter of replacement (European for Jew) but, as I have suggested, of displacement and now theological reconfiguration. European Christians reconfigured the vision of God’s attention and love for Israel, that is, they reconfigured a vision of Israel’s election. If Israel had been the visibly elect of God, then that visibility in the European imagination migrated without return to a new home shaped now by new visual markers. If Israel’s election had been the compass around which Christian identity gained its bearings and found its trajectory, now with this reconfiguration the body of the European would be the compass marking divine election. More importantly, that new elected body, the white body, would be a discerning body, able to detect holy effects and saving grace. Valignano performs this new reconfigured vision of election precisely in the discernment of racial being.

The mobility and flexibility of the racial scale carried with it a doubtfulness of being, a strong suspicion of instability precisely at the point of embodied Christian commitment. Without Israel as the point of elected stability, the idea of an elected people became an idea without its authentic compass and thereby subject to strange new human discernment. Valignano discerns in two ways—those capable of salvation and those capable of the ministry, priesthood, and ecclesial leadership. At the bottom, chained to the deepest suspicion of incapability, are the conversos (or marranos) and moriscos. Valignano locates Africans with these New Christians and Christian Moors as those he strongly doubts capable of gospel life: “They are a very untalented race … incapable of grasping our holy religion or practicing it; because of their naturally low intelligence they cannot rise above the level of the senses …; they lack any culture and are given to savage ways and vices, and as a consequence they live like brute beasts…. In fine, they are a race born to serve, with no natural aptitude for governing…. But through a just though hidden judgment of God, they are left in that state of impotence and regarded as a sterile reprobate land which gives no hope of yielding fruit for a long time to come.”40 This astounding statement, reflecting on the people of Monomotapa in Mozambique, shows Valignano drawing the logical conclusion of black incapacity—reprobation. Reprobation is not simply the state of existence opposite election; it is also a judgment upon the trajectory of a life, gauging its destiny from what can be known in the moment. Reprobation joins the black body to the Moor body and both to the Jewish body. All are in the sphere of Christian rejection and therefore of divine rejection. At the other end of capability are the Japanese (and possibly the Chinese). As is apparent in the quotation given above, Valignano believed that as a white race the Japanese showed potential to enter the depths of Christian formation. The Indians, as also noted above, fell short of the Japanese and Chinese. A sense of reprobation lies with them as well: “A trait common to all these people (I am not speaking now of the so-called white races of China or Japan) is a lack of distinction and talent. As Aristotle would say, they are born to serve rather than to command. They are miserable and poor beyond measure and are given to low and mean tasks…. Most of them are very poor, but even the rich tradesmen have to hide their wealth from their tyrannical rulers. They go half-naked and live unpretentiously. More, they are all of a very low standard of intelligence.”41

A Japanese convert, in Valignano’s view, could become as good a Christian as a purebred European or an even better one. Their intelligence and cultural superiority made Japan a fertile, attractive ground for Christian growth. Valignano knew that the work in China and especially in Japan was the most sought-after assignment for Jesuits because of they could identify with intelligent and affable “white” Asians. Thus only the very best workers were allowed on that ground.42 His comparative analysis also informed his classification of the people appropriate for ecclesial service. Most appropriate were purebred Portuguese (that is, Europeans). Second in terms of appropriateness but regarded with significant reservations were those of pure European parentage but who had been born in India or elsewhere “outside.” After these groups, the so-called half-born were quite dubious: mestiços (or Mestizos), also called Eurasian, those born of Portuguese fathers and native mothers; and castiços (or Castizos), those born of European fathers or mothers and Eurasian or mestiço mothers or fathers. Clearly beyond the veil of possibility for service were those whom Valignano termed the “dusky races, [as they are] stupid and vicious,” and those of Jewish blood. Valignano’s analysis proved decisive, as Rome agreed with all his recommendations for recruitment and the formation of priests in and for mission lands, especially Jesuits.43

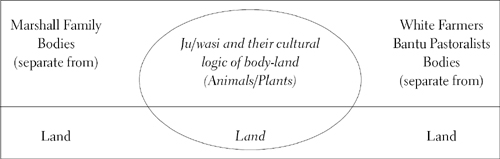

It would, however, be a mistake to summarize this comparative performance as simply a particular historical characteristic of the Jesuit. Alessandro Valignano was not an innovator in either the theological or historical sense. His orthodoxy was without question, his spirituality and political ability of the first order. He spoke with the mind of the church and with the church in mind. What makes his comparative work so crucial is that in him one sees Christian formation being reconfigured around white bodies. A schematic of this reconfiguration might begin with the constellation shown in figure 1.

As may be seen from the arrows of the schematic, black and white add precision and definition in discerning peoples’ salvific possibilities. Technically, doctrines of election first refer to peoples, not individuals. However, individuals may be configured within the overall assessment of a people’s salvific viability. Black indicates doubt, uncertainty, and opacity of saving effects. Salvation in black bodies is doubtful, as it was in (Christian) Jews and Moors. White indicates high salvific probability, rooted in the signs of movement toward God (for example, cleanliness, intelligence, obedience, social hierarchy, and advancement in civilization). Europeans reconfigured Christian social space around white and black bodies. If existence between Christian and non-Christian, saved and lost, elect and reprobate was a fluid reality that could be grasped only by detecting the spiritual and material marks, then the racial scale aided this complex optical operation. For example, Valignano notes that Africans, like other reprobates, show the following characteristics: they go around half naked, they have dirty food, practice polygamy, show avarice, and display “marked stupidity.”44 The stability within this fluid reality is white and black. The racial scale signifies not only a point of exchange—white European election for Jewish election—but also a process of becoming.

Figure 1. A Trajectory of Salvific Possibilities

Valignano inherited his supersessionist thinking. His use of that thinking, however, brilliantly exhibits its development at this pivotal moment. Through a racial calculus, comparative analysis becomes the new inner logic of how one deploys supersessionist thinking. Supersessionist thinking depends on acts of discernment, that is, of reading the observable for its actualization. Valignano actualizes not simply a way of reading native bodies but a way of inscribing native bodies in the drama of redemption’s journey, a journey marked by easy paths (white bodies) and rough terrain (black bodies).

I examine this new inner logic of supersessionist thinking in the next chapter as I consider the thought of José de Acosta. But one important implication of this development stands out: in the age of discovery and conquest supersessionist thinking burrowed deeply inside the logic of evangelism and emerged joined to whiteness in a new, more sophisticated, concealed form. Indeed, supersessionist thinking is the womb in which whiteness will mature. Any attempt to address supersessionism must carefully attend to the formation of the racial scale and the advent of a new vision of Christian social space. Valignano’s inherited derogatory vision of black flesh was also present among Muslims.45 Indeed, one would be hard-pressed to find a positive view of the sub-Saharan African in this time, especially given the attractiveness of the black slave trade. Muslim slave traders drew aesthetic distinctions between white European slaves and black sub-Saharan African slaves, not only because white slaves could potentially bring more money in their sale to Christians, but also because black slaves were considered inferior in body and mind to whites.46 The fifteenth-century Islamic historian Ibn Khaldun noted that “[Negroes] have little that is (essentially) human and possess attributes that are quite similar to those of dumb animals.”47 Like Christianity, Islam held a comparative sensibility that distinguished, in the words of the tenth-century Persian Islamic historian Tabari, all blacks from the Arabs and Persians, who have “beautiful faces and beautiful hair.”48 However, my concern is not simply with the operation of a derogatory view of black bodies, but also with how Europeans reconfigured Christian social space and in turn entered into their own act of displacement.

Displacement operates within the expansion of worlds. In time the Iberian world will extend from South America to Africa to India to China to Japan to Australia.49 These nations will not be alone in reach or remain preeminent in power. But the reach of the Iberian nations or any other nation existed within the wider vision of the church. As I have shown, the world of the church was coextensive with that of these young colonialist powers and worked in and through them as well, providing a theological framework that extended their identities onto a spiritual plane and enabled them to articulate their forms of life in their encounters with other peoples. This extending of worlds deeply affected the African as well. In fact, mercantile and theological interests conversed and converged on the African at this moment, not only vivifying the idea of perpetual slavery, but also drawing African bodies onto a plane of existence that involved constant spiritual and material comparison with white bodies.

The subtleties of this displacement moved simultaneously in two directions. The first was conceptual, exhibited in a comparative habit of mind that was facilitated by the racial scale and that was organized within a theological matrix. The second was material, activated by the joining of European and African bodies within an economic arrangement that indicated a fundamental transforming of space. Europeans were willingly leaving their homes. Newly discovered natives were unwillingly being taken from their lands. Historically, this is so obvious as to seem trite, but the parallelism at work here, while almost imperceptible, was earth shattering. With this leaving, this exiting, one approaches the depths of this theological mistake. It will not be easy to articulate the material reality of displacement because it is the articulation of a loss from within the loss itself. To fully tell it requires the very thing that is lacking, indigenous voices telling their own stories of transformation through current concepts of space, identity, and land. Equally difficult is the attempt to peer into a theological mistake so wide, so comprehensive that it has disappeared, having expanded to cover the horizon of modernity itself.

I must now engage in an act of fragment thinking in hopes of seeing the new order that emerged during the age of discovery and conquest. In “gather[ing] up the fragments that remain that nothing may be lost” (John 6:12), I want first to examine another episode in the life of Alessandro Valignano that will help uncover the reality of loss inside the movement of displacement.

Approaching Holy Week in March of 1581, two years after his arrival in Japan, Valignano and his retinue set out on horseback to the city of Miyako (now Kyoto) to visit the Azuchi castle, home of the most powerful leader in Japan, the ruler of Tenka, Oda Nobunaga. Valignano, as was customary, was bringing gifts for the dignitaries: sets of vestments, small oil paintings, musical instruments, books, rosaries, and other things. However, the most interesting thing Valignano brought along with him for that eventful visit was his slave, a dark-skinned African. The intricate route to the castle, past Yao, Wakae, Sanga, and Okayama (Kawachi), crossing the river Yodogawa, and on to Takatsuki, took several days, right into Tuesday of Holy Week, and en route, as the historian Josef Franz Schütte relates, the party drew special attention: “All along the way the people gathered in crowds curious to catch a glimpse of the party; the giant figure of the visitor and the dark-skinned Negro who accompanied him as servant were objects of special interest.”50 Arriving in Takatsuki, Valignano performed that most sacred of liturgies, of Holy Week and Easter, celebrating the body of Christ, in suffering, death, and resurrection. He then proceeded to Miyako to prepare his own body for formal presentation and audience with the ruler. The parallel of presentation of bodies here is striking. Valignano was an usually tall man (over six feet), but as he and his black slave stood in the presence of Oda Nobunaga, the ruler’s interest turned to the African. Nobunaga was not alone in showing utter fascination with the African. A large, excited crowd had gathered outside the place where Valignano and his attendants were housed, hoping to catch sight of this black body. Some people had come to blows jostling for position. As he stood before Nobunaga, just a few days after Easter, the body of this African came under careful scrutiny. The astonished and puzzled ruler ordered that the upper body of this black man be uncovered, and then he proceeded to have him washed over and over again to see if the blackness would disappear.51

Valignano and his black slave standing there together before the ruler are instructive. Two bodies are in presentation with a third body in the background. For Valignano, it is the third body, that of Christ crucified and resurrected, that has brought him to these shores. Yet the crucial body at this moment is not the body of Jesus, but the body of an African enslaved—Hoc est enim corpus meum (This is my body). Nobunaga performs another liturgy after Holy Week, an anti-liturgy, as it were, in which the stripping and repeated washing of the dark African confirms his identity as black and slave. This moment of visitation represented the joining of the white body to the black body—together they appear. Valignano stood before the ruler and presented the new world of the “southern barbarians,” as they were called by the Japanese. He showed European mastery over lands and peoples by having this black body in servitude. Though he spoke and presented himself and his church in friendship, this was also a moment of closure, as the African was not permitted to speak for himself. Indeed, even if he had spoken his native language he would probably not have been understood. Standing there half-naked, he had been taken from his home and given a new identity calibrated to his body and articulated by his Christian master. There in that new space the slave had no name, unless it was given by Valignano. For Ruler Nobunaga, whoever this African was would issue out of an examination of his black body and the words of the visitor.

Valignano entered this moment of dislocation by choice, the slave by force. In this new space, Japan, Valignano is a white man among “white people,” established in the knowledge that being there was not a disruption of his identity, but an expansion of it into a spiritual and quasi-national network. That new space, however, meant utter disruption for the African. Gone was the earth, the ground, spaces, and places that facilitated his identity, and what remained, embodied in his master, was a signified and signifying reality of whiteness, not simply by his master’s speech but by the very location of the master’s body operating in power next to his.

This episode exemplifies a spatial disruption that the European Christian would enact and to which he would be almost oblivious, but never innocent. The age of discovery and conquest began a process of transformation of land and identity. And while worlds were being transformed, not every world was changed in the same way. Peoples different in geography, in life, in different worlds of European designation—Africa, the Americas, Europe—will lose the earth only to find it again in a strange new way. The deepest theological distortion taking place is that the earth, the ground, spaces, and places are being removed as living organizers of identity and as facilitators of identity.

What if your skin was inextricably bound to “the skin of the world,” to borrow that marvelous phrase from Calvin Luther Martin’s text The Way of the Human Being.52 What if it seemed strange, odd, and even impossible for you to conceive of your identity apart from a specific order of space—specific land, specific animals, trees, mountains, waters, and arrangements of days and nights? Martin, a historian and quasi-theologian who spent years among the Yup’ik Eskimos on the Alaskan tundra and significant time in the Navajo nation, suggests an order of things present among the indigenous peoples of the New World that a mind detached from deep participation with the earth cannot easily appreciate. In contrast Martin points to a different identity form: “People who can define themselves as cardinal points, primary colors, segments of the day, the seasons, even the journey of life itself—people such as this are clearly engaging a reality different from the usual western points of reference.”53

It is a truism to say that humans are all bound to the earth. However, that articulated connection to the earth comes under profound and devastating alteration with the age of discovery and colonialism.54 A central overlooked implication of that sense of connection is the articulation of place-bound identity, a form of existence before or “below” race, within place itself. In Martin’s account, “Native Americans universally maintain that human and animals were made to occupy the same skin—the skin of shared personhood. Here at creation’s origin, there was nothing really to distinguish humans from animals: one lived in human shape and yet was still groundhog, rabbit, tortoise, or what have you. In the native world, men and women existed more broadly as plenipotential people, people who ‘are themselves—a Clam, a Dog, a Birch Person—yet they take human shape as well. Each form contains the other. In some ways, they are seen as being both at once.’”55 Before reading this as a form of ethnographic essentializing (Martin, remember, is a historian, not an anthropologist), one should see the important claim Martin makes, a claim that joins many peoples who remember that they are tribes or peoples. Identity here requires spatial realities endowed with irreducible, even irreplaceable points of reference. What Martin invokes is difficult to capture because it must be read in light of the complex history of the social construction of Indianness and the very real politics of Indian identity in America.56 Like the African, the Indian is a necessary fiction, a pothole-filled pathway made through discursive practice that allows one to move toward understanding what is at stake in the loss of ways of life and the troubled yet admirable attempts to gather the fragments that remain.57 In this regard, one should not stumble at the usage of Indian or African or of invoking what I understand as an aspect of tribal reality for fear of falling into mind-numbing essentialism.

The greater trap is the failure to see the specifics of the loss for indigenes that includes but is not completely captured by European discursive hegemony. As Philip Deloria points out, identity construction must be understood in the context of land appropriation: “The indeterminacy of American identities stems, in part, from the nation’s inability to deal with Indian people. Americans wanted to feel a natural affinity with the continent, and it was Indians who could teach them such aboriginal closeness. Yet, in order to control the landscape they had to destroy the original inhabitants.”58 Deloria correctly notes a history of Indian-use which, like African-use, bolsters a sense of freedom and independence from the trappings of the old European world, connection to land as private property, and the possibilities of being self-made in America. The sense of connection Martin seizes upon is bound neither to nobility myths nor to European Indian invention. It is not “imperialist nostalgia.”59 Martin echoes the words of native peoples, creatively using language to capture that which is beyond the sight of many. He tells the story of an Eskimo from a tiny village by the Bering Sea, Charlie Kilangak, whose Yup’ik name means Puffin. He explained to Martin exactly what it means to be Puffin:

I am a puffin.

I live on the cliffs or on the steep hillsides.

I know and choose to live where my family will be safe.

I love to fish, and know which fish to ingest for my children.

I could both fly in the skies or under sea and master the winds and the currents.

I know where to go by looking at the world around me.

I am a puffin … from … my ancestral tree, and in blood.

I choose to dress in black and white so my children will know who they are too.

I have this wonderful colorful beak. It helps me identify my own kind, so others would know who I am.

I am a puffin, and I am what my creator has made me to be.

I am a puffin, and my son is too.60

Martin tells another story of a young Iroquois man who had an argument with his Iroquois uncle about Indian identity. The uncle asked the young man, who had just graduated from college, who he (the young man) was?

When the nephew matter-of-factly replied that he was who his name said he was, the older man was not impressed. “Yeah, that’s who you are, I guess.” Pause. “Is that all?” Sensing he was being set up for something, the young man expertly traced his parentage on both sides and then ran back through his clan. [Seeing that he was not giving the answer the uncle wanted, he conceded, angrily asking the uncle,] “Well, who the hell am I then?” The older man calmly replied, “I think you know but I will tell you. If you sit here, and look out right over there; look at that. The rocks: the way they are. The trees and the hills all around you. Right where you’re on, it’s water…. You’re just like that rock…. You’re the same as the water, this water…. You are the ridge, this ridge. You were here in the beginning. You’re as strong as they are. As long as you believe in that … that’s who you are. That’s your mother, and that’s you. Don’t forget.”61

Martin is not romanticizing Native Americans, claiming for them some essentialized ecological genius, but instead is simply noting the remnants of a sensibility concerning identity. We are the very things we may invoke spatially.62 His recounting of part of a Navajo hymn illustrates this:

The mountains, I become part of it …

The herbs, the fir tree, I become part of it.

The morning mists, the clouds, the gathering waters.

I become part of it.

The wilderness, the dew drops, the pollen …

I become part of it.63

This Native American insight draws one into a self-description built within a vision of creation bound to specific locations. This union with the world through “unbounded kinship,” as Martin calls it, turns on geographic specificity64 and on a kinship with plants, places, and animals.65 Martin isn’t noting a recalcitrant “primitivism” heroically standing against the tides of modernity. Rather, he has come upon ancient ways of articulating existence. That articulation was rooted in an ongoing conversation with the world in a “reciprocal aesthetic that announces kinship.”66

Martin suggests, unsympathetically, that those first Christians who came to the new worlds “were at the furthest limit of their conception of the real and though utterly unaware of it were fingering the ‘skin of the world.’” Those Christians went unknowingly beyond geography into identity.67 They entered what for them was a frontier of strangeness. Already fearful and angled toward isolationist practices, they enacted a spatial vertigo, renaming places, peoples, and animals and reconfiguring life.68

Christian faith and theology carry within them the possibilities of knowing and renarrating identity with geography. The Greek Orthodox theologian S. A. Mousalimas tells the story of an Orthodox Yup’ik hunter whose way of life articulates his Christian identity through his familial oneness with animals and land.69 But these were possibilities of self-articulation never to be fully realized, never to be truly explored.