John William Colenso set foot on the shores of Durban at Port Natal, in what is now South Africa, on Monday, January 30, 1854. This newly minted bishop of the Anglican Church was about to begin one of the most important odysseys of a missionary bishop in the history of the Christian church. The world of Bishop Colenso was far removed from that of José de Acosta. Colenso was an Anglican bishop of the nineteenth century, shaped by a Protestant church and an England still feeling the effects of the French Revolution, immersed in the industrial revolution and in the intellectual revolution that was the Enlightenment. Acosta was a Jesuit of the late fifteenth century, shaped by a Roman Catholic Church and a Spain being transformed by the discoveries of new worlds and troubled by the overturning of ecclesial life brought about under the Protestant Reformation. Yet both were missionaries at the emergence of two nation-states, successive global world powers, and both entered new worlds as those worlds were being radically transformed.

The forty-year-old man who came to Natal as its first Anglican bishop in 1854 had not had an easy life. The untimely death of his mother and the financial collapse of his father’s business meant that young John had been largely responsible for raising his younger siblings. His early life was defined by unrelenting hard work, but also by an innate intelligence and abiding academic ambition. At St. John’s College, Cambridge, he distinguished himself as a brilliant student, particularly in mathematics, and as an extremely overworked student owing to his chronic financial situation. Yet John was from the beginning a very serious Christian, and his commitment to his faith and the church deepened as he progressed through his education.1

Colenso’s intellectual vision was shaped by the theological romanticism of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Frederick Denison Maurice. These two thinkers, introduced to him by the young woman who would become his lifelong companion, Sarah Frances Colenso (née Bunyon), drew his vision out from the Protestant evangelicalism of his early years into a wider theological imagination characterized by Enlightenment sensibilities.

Coleridge introduced him to the idea of a universal religious consciousness that only needs to be accessed inwardly to establish its validity. In this regard, Coleridge’s views had much in common with the thought of the great German Romantic theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher. The Christian God articulated by Coleridge was not dependent on proofs, evidence, or demonstrations. As Coleridge says in his famous text Aids to Reflection, “All the (so called) demonstrations of a God either prove too little, as that from the order and apparent purpose in Nature; or too much, namely, that the World is itself God.”2 Coleridge offered Colenso an intuitive faith that gently but firmly drew space between itself and the Scriptures, releasing the Bible from service as the basis of Christian faith itself.3

In a telling passage that presages much of Colenso’s intellectual journey, Coleridge comments on the meaning of the well-known text “There is no other name under heaven by which a man can be saved, but the name of Jesus” and offers a view of the moral Bible, a Bible freed from literalist interpretation and drawn into a wider pedagogical vision:

It is true and obligatory for every Christian community and for every individual believer, wherever the opportunity is afforded of spreading the Light of the Gospel, and making known the name of the only Saviour and Redeemer. For even though the uninformed Heathens should not perish, the guilt of their perishing will attach to those who not only had no certainty of their safety, but who are commanded to act on the supposition of the contrary. But if, on the other hand, a theological dogmatist should attempt to persuade me, that this text was intended to give us an historical knowledge of God’s future actions and dealings—and for the gratification of our curiosity to inform us, that Socrates and Phocion, together with all the savages in the woods and wilds of Africa and America, will be sent to keep company with the Devil and his angels in everlasting torments—I should remind him, that the purpose of Scripture was to teach us our duty, not to enable us to sit in judgment on the souls of our fellow creatures.4

Coleridge inserts the peoples of Africa and America as tropes for those at the farthest edge of soteriological possibility. They are the “uninformed Heathens” who, along with Socrates and Phocion, had been relegated in the dominant theological systems of his day to damnation and tormenting hell. Coleridge had little patience for such an inadequate idea of the reality of the divine. His compelling intellectual vision grew out of his deep and abiding involvement with the thought of Immanuel Kant and the German Idealist tradition articulated in the works of Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Friedrich Schelling, and Schleiermacher. Kant’s profound reformulation of what constituted adequate theological speech found exciting articulation in Coleridge, who channeled the sensibilities of German Romanticism into English. Most notably, Coleridge not only enabled religious consciousness and Enlightenment reason to happily coexist but also suggested that reason properly understood manifests religious consciousness. Unlike pre-Kantian visions of religious truth based on objective metaphysical truth, Coleridge echoed Kant’s critique of such thinking and invited people to turn inward in order to locate the source of the truth of religion. Colenso will carry forward this Coleridgean critique of the older (pre-Kantian) theological vision as well as the deployment of Africans as tropes of damnation to indicate a kind of theological vulgarity.

Maurice offered Colenso a breathtaking vision of a loving Father-God, one whose power flows through indefatigable love. For Maurice, the divine presence in the world was already a saving presence: “The truth is that every man is in Christ; the condemnation of every man is, that he will not own the truth; he will not act as if this were true, he will not believe that which is the truth, that, except he were joined to Christ, he could not think, breath, live a single hour.”5 From Maurice, Colenso inherited this christological universalism, which greatly shaped his powerful humanitarian sensibilities. He also gained from Maurice, himself a disciple of Coleridge, a vision of theology and Christian doctrines driven by an overarching moralist hermeneutic. All theological statements and doctrinal axioms, if they are rooted in universal truth, issue really only in lessons for the moral life.6 The goal of theological statements is to deepen one’s understanding of the moral structure of human existence. In this way, doctrinal statements in the powerful construal of Maurice drew attention to humans’ life together and the formation of their character. Much in line with German Romanticism, Maurice envisioned religion and religious language’s central purpose to more clearly express the authentic human person in his or her individuality and universality. Thus Christian doctrine functioned inside a kind of circularity. That is, theology and doctrine, as the articulations of universal moral truth, only completed what was already possible to know, even if in embryonic form, through nature. Colenso seized on this moralist hermeneutic and explicated a vision of God that did not require doctrine with any metaphysical density for the formation of Christian identity.

Colenso, however, arrived in Natal not simply a budding theologian; he was also a translator come to Africa to convert and educate. He came to the colony of Natal, nestled on the eastern seaboard of southern Africa between the majestic Drakensberg Mountains to the west and the Indian Ocean to the east and between the Thukela River to the north and the Mzimkhulu River to the south. It was home to many peoples, including the Zulu people. In the face of the ubiquitous presence of Europeans, the many peoples that traditionally inhabited that region had seen and were seeing their ancient worlds collapse and reemerge fundamentally changed.

The peoples of this region were being squeezed on all sides by Europeans. The Portuguese presence to the northeast and especially at Delagoa Bay had for decades before Colenso’s arrival disrupted life by drawing native peoples into detrimental trading practices involving ivory, hides, maize, and slaves. The Portuguese inserted their hunting and trading practices into an already fragile ecological system that saw, in the years prior to Colenso’s arrival, environmental strain through drought and famine. Portuguese hunting and trading also affected sociopolitical systems easily manipulated through trade. These capitalist operations resulted in stimulation of tribal conflict and reconfiguration and ultimately in the disruption and displacement of peoples.7 The British presence in the southeast and the Boer/Voortrekker presence in the south-southwest created an unrelenting appetite for land and laborers that drove ever-increasing patterns of deception, subterfuge, manipulation, injustice, and violence. Armed with weapons given to them by the British and Dutch, and often in collusion with them, the Griqua, Kora peoples and other armed horsemen based on the southwest middle Orange and lower Vaal rivers descended upon unsuspecting peoples, raiding and killing and taking prisoners who would become laborers for the British and Boer colonialists.8 Chiefs, tribes, and individuals were also being placed in a moral universe controlled by white opinion displayed in print media. The morality or immorality of every African was determined by how much he supported white interests, accepted European culture, and yielded land, labor, and life to European control.9

Furthermore, by the time of Colenso’s arrival, settler and merchant interests were beginning to narrate their presence as salvific, bringing order to chaos and cultivation to empty, uninhabited lands. They attributed the chaos to the legacy of a Zulu chief, Shaka Senzangakhona, and his terrorist behavior. What would soon come to be designated as the Mfecane, “the crushing, the destroying,” in which Shaka and the Zulus were interpreted as the central cause of disruption, disorder, displacement, and death in the region, had its beginning in European discursive control of the multiple narratives Africans themselves told of intertribal conflict and war. Shaka was only one of many excuses used by the white settlers for aggressively seizing lands and pulling peoples from the hands of “despotic chiefs” and into labor systems.10 African agency was intact; there were intertribal conflicts, war, violence, and death as chiefs constantly sought to consolidate power, establish stability, and ensure the peace and prosperity of their peoples. However, African agency was always articulated ultimately by settlers and settler-merchants, who made sure that the grand narrative performed in England and in other communication centers of the Old World juxtaposed African despotism to white benevolence.

The colony of Natal was saturated with two interrelated forms of desire: the merchant and the missionary. Settler existence began in 1824 with the entrepreneurial interests of traders from the Cape colony to the southwest. Francis Farewell and Henry Francis Fynn, along with other merchants, came in search of trade agreements with Shaka, the Zulu king. The Boer gained control of the colony and the surrounding area after a bloody conflict with the Zulu and the defeat of the Zulu king, Dingane kaSenzangakhona, son of Shaka. They had named the spoils of their war the Republic of Natalia. But the Boer victory was short-lived. The colony became property of the British crown in 1842 after the British pushed out the Boer/Voortrekker. British involvement in this area was at first less than enthusiastic because Natal was not considered an area brimming with lucrative possibilities. But the British believed that Boer expansion was a threat that merited their military intervention. Natal, however, struggled to fully integrate itself into the imperial economy.11

Caught in the middle of all this were the many native peoples. The attempt to reestablish and refashion themselves became a permanent characteristic of their existence. On the one hand people were trying to maintain precolonial African institutions with chiefs, indunas, headmen or chiefly councilors, and ibutho, age-grouped men or women who served the chief by carrying out various duties. Indigenes, who functioned without that kind of institution, wished to remain free of chiefs while maintaining common traditions and practices. On the other hand, the white settler presence had brought the entire region into a capitalist system such that no native agricultural practice or tradition involving the land would go untouched or unaltered. All the land and animals, especially the cattle, came steadily under settler influence or control.

The settlers exploited Natal as a significant entrepôt. Because of the linkages between farming efforts and trade, native inhabitants’ lives were steadily woven into ever-expanding commercial networks. White settlers’ aggressive desire to make life profitable in Natal was matched only by their impatience with indigenous landowners as their direct competition in trade and farming. Moreover, white settlers’ need for laborers was feverish, and Africans outside of their control were a source of deep frustration. These Africans, for their part, were increasingly displaced even on their own ancestral lands. Pursued by land speculation companies such as the London-based Natal and Colonization Company, which allegedly owned hundreds of thousands of acres, many displaced peoples found themselves living the lives of squatters and tenants. Many contracted as labor tenants for white farmers, or they rented land and were subject to arbitrary rules, laws, and evictions.12

The land and native life were also steadily woven into missionary networks. Between 1835 and 1880, there were at least seventy-five mission stations covering the Natal, Zululand, and Mpondoland, missions representing a host of denominations, including Methodist, Scottish Presbyterian, Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Church of England, Congregational, and American Presbyterian. German, Swedish, Portuguese, English, Dutch, and American missionaries spread across the Natal landscape building churches and schools and proselytizing Africans.13 Some societies worked closely with colonization and land companies such as the Joseph Byrne Emigration and Colonization Company, establishing enterprising settlers and planting missionaries in one single operation. This is the world that John Colenso, bishop and translator, entered.

It would be impossible to understand the life and actions of Bishop Colenso in his new world without considering the one man who had the single greatest effect on his life and that world, Theophilus Shepstone. There were others who were important in Colenso’s life—his fiercely intelligent wife, Frances Colenso; the presiding bishop of Cape Town, Robert Gray, with whom Colenso was to wage the theological struggle that was to define his public image in England; and William Ngidi, with whom he studied the Zulu language and who was to become a crucial figure in Colenso’s theological program. All were crucial, yet in truth, Shepstone is the necessary hermeneutical horizon upon which to grasp the theological vision Colenso enacted in the new world of Africa. Indeed it would be quite appropriate to characterize the young bishop’s early years in Natal as the Colenso-Shepstone years. Upon Colenso’s arrival in Natal, the two men quickly became close and began what looked to be a deep and abiding friendship.

Shepstone was in many ways the ideal companion for a missionary translator come to a strange new world. He was the son of a Wesleyan missionary, John William Shepstone, who shared the same first and middle names as his new-found friend. Theophilus grew up in Methodist itinerancy in the Cape colony. This meant that home for him and his siblings had been in Bathurst, Theopolis, Grahamstown, Wesleyville, Morley, and a host of other places on the Cape. It also meant that Theophilus’s gift of language acquisition was to become quite useful as he mastered the Nguni languages, that family of languages spoken by the many groups that inhabit what is now southern Africa. By the age of fourteen, Theophilus was already aiding missionaries in translation work.14 He was also to serve with distinction as an interpreter for colonial officials and the military. A deeply devout Christian man, Shepstone understood missionary life and what was necessary for it to thrive. Moreover, he had gained intimate knowledge of native practices, cultural logics, and belief systems that he used to great effect. So when Colenso found Shepstone in Pietermaritzburg at the beginning of his first visit to Natal in 1854, he thought he had discovered a gift set in place for him by God.

One must understand Colenso and Shepstone as two translators. Although it would be several years before Colenso gained mastery of the Zulu language and Nguni language systems, the work of translation was mirrored in the lives of these two men, with one significant difference: Shepstone translated much more than Christianity into native worlds. He stood at the center of the translation of native worlds into European hegemony. Shepstone was in charge in Natal. Colenso’s early years in Natal were just the opposite of the period of very strained relationship between the theologian Acosta and the Christian colonial ruling agent Viceroy Toledo. Colenso and Shepstone were two sides of the same coin, joined in the same process, translation. Colenso brought Christianity into vernacular languages, and Shepstone used vernacular languages to bring the natives into colonial existence. Colenso had willingly and with great joy stepped into the Shepstone system.

In 1846, at the age of twenty-eight, Theophilus Shepstone (whose first name means “lover of God” in Greek) became the diplomatic agent to the native tribes of Natal. Later named secretary for native affairs, Shepstone ruled the colony for thirty years. His Nguni name, Somtsewu, means “Father of Whiteness.”15 And as the great white power, Shepstone put in place a system of control, masterful in its use of native logics. The historian Jeff Guy suggests that the reason Colenso and Shepstone became fast friends was not only because they were close in age and personality, but also because they shared a vision of how to move African society forward:

Shepstone and Colenso held that the proper answers to the challenges created in a rapidly changing social situation should be found in the utilisation of older social forms. Shepstone argued that it was necessary to retain and develop those aspects of African life which did not conflict with civilised standards and that care had to be taken not to provoke the African into resistance by violently changing his way of life. From Maurice, Colenso had learnt that the good worked by the presence of God could be discovered in all men, and that the missionary had to identify this and build upon it—not destroy everything in an attempt to rout that which was abominable.16

Guy surmises that Colenso and Shepstone shared a native anthropology: “Colenso had rejected the idea of hopelessly fallen man, Shepstone the totally barbarous one. It was upon this that their friendship was founded.”17 While this sunny summation of their comparable conceptual dispositions may be true, it also points toward the deeper strategies of paternalistic manipulation that will characterize the Shepstone system and mark South African life right up to and through the apartheid years.

Shepstone bore a reputation as an expert on the native mind, a reputation he endlessly cultivated through his administrative machinations. One sees in Shepstone the outcome of linking language mastery to whiteness. In one way, his mastery of native dialects joined the work of the missionary and that of the colonial agent in the colonization of language. Yet in another way, his language mastery shows the growth of colonialist operations from missionary roots. It would certainly be unfair to paint these missionaries as nothing more than colonialists. However, one must not miss the point of the unintended consequences of language acquisition and the cultivation of intimate relations. Personal (missionary) knowledge is put to colonialist use. As he transitioned from a missionary translator and helper to colonial interpreter to colonial agent to the central power running the colony, Shepstone was poised to build the colonialist system on top of existing native networks. This was the heart of his system.

Shepstone’s deepest impulse was to gain full control of the African. His initial plan, which was rejected by the colonial office for its cost, was to place all Africans on reservations under the strict control of white magistrates.18 What Shepstone ultimately managed to do was place a canopy of British administrative and judicial structure on top of precolonial African institutions.19 What this meant was that Shepstone himself would become the (operational) chief of chiefs, with everyone under him—resident magistrates, administrators of native law, chiefs, indunas, and headmen. On the surface this system appeared to respect context, indigenous life and custom. In truth it was a system of profound control. Africans would be governed by native law administered by indunas, under the guidance of chiefs. Above the chiefs, overseeing the administration of native law, were the white magistrates and administrators, and over them all was Shepstone, the lieutenant-governor (the supreme chief), and the Legislative Council. Shepstone ensured loyalty throughout the system by returning a portion of the fees, fines, and in-kind penalties (for example, cattle) to chiefs and indunas as payment for administering justice. But the demonic genius of the system lay in its taxation schema.

Many white settlers and farmers, especially those from inland farms and villages, despised Shepstone and his system of distributing land to Africans. They believed he favored the Africans by granting land rights, allowing them to live on tribal lands as well as on land owned by land companies, and by allowing them to participate in the emerging market economy. All of which meant that Shepstone’s policies created a small, stagnant pool of black labor. On the surface, his policies did give the appearance of leaving the Africans’ ways of life intact, but in truth Shepstone had chained African ways of life tightly to capitalism. He taxed almost everything associated with the everyday practices of indigenous life. Chiefs had to pay a hut tax calibrated to the number of huts in their villages; an increase in the number of huts through population growth meant increased taxes. There were fees for marriage and divorce, and fines for violations of policies and laws. But the greatest revenue scheme involved the custom duties on imported goods. Through the Legislative Council, Shepstone was able to place charges on goods that were used exclusively by Africans, while goods used by white settlers carried slight charges or were duty free. Goods bound for inland Africans also were priced higher.

On the one hand, Africans earned money by supplying food to the markets through backbreaking labor on their land, by trading within a trading system unfair to them, and by working for white employers under conditions that matched and exceeded the harshness of life in England during the emergence of industrial capitalism. Furthermore, they were taxed far more than the white settlers. As the historian Norman Etherington notes, “Whenever more revenue was needed, new charges were levied on African consumer goods.”20 Indeed, the government was paid for on the backs of Africans.21

The powerful coastal farmers and merchants, overseas businessmen, and colonial companies in England all appreciated Shepstone and his policies. They understood he had achieved a remarkable level of social stability and financial solvency through his operations. Indeed, Shepstone ambitiously promoted his system as a model transferable to other parts of Africa.

It is not clear whether Bishop Colenso could see at the beginning of his life in Natal the devil in the details of the Shepstone system. What is clear is that Colenso agreed in principle with Shepstone’s policies because he was at heart, like Shepstone, a British citizen deeply committed to the colonialist civilizing project in Africa, and he was shaped to read African societies through white paternalism. Yet from the very beginning of his time in Natal, Colenso demonstrated that he was not perfectly aligned with the Shepstone way of treating the native peoples. During his first ten-week journey in Natal, Bishop Colenso recounted the events of February 10. On that day he went with Shepstone and his aide to survey the land a few miles outside of Pietermaritzburg where he would build his episcopal residence, Bishopstowe. Upon his return to the city, he learned that a native worker had been crushed by a stone. Bishop Colenso was moved as he observed the grief of the dead man’s brother and found the bond between himself and the Africans growing closer. It was after this event that Ngoza, one of Shepstone’s native headmen, wanted to pay his respects to Colenso. The event of their meeting typifies the colonial operation as well as Colenso’s ambiguous relationship to it. Colenso had been advised to “keep the Kafir waiting.” After he dressed, he stepped into the courtyard where Ngoza was waiting:

In due time, I stepped out to him, and there stood Ngoza, dressed neatly enough as an European, with his attendant Kafir waiting beside him. I said nothing (as I was advised) until he spoke, and, in answer to a question from Mr. Green, said that he was come to salute the in Kos’. “Sakubona,” I said; and with all my heart would have grasped the great black hand, and given it a good brotherly shake: but my dignity would have been essentially compromised in his own eyes by any such proceeding. I confess it went very much against the grain; but the advice of all true Philo-Kafirs, Mr. Shepstone among the rest, was to the same effect—viz. that too ready familiarity, and especially shaking hands with them upon slight acquaintance … did great mischief in making them pert and presuming. Accordingly, I looked aside with a grand indifference as long as I could, (which was not very long,) and talked to Mr. G., instead of paying attention to the Kafir’s presence.22

Colenso entered the courtyard in the colonialist persona. Ngoza in European dress stood in front of Colenso, while Colenso, by instruction, minimized his presence by ignoring him. Silence, indifference, and indirect speech all performed the colonialist relation, and the bishop enacted it perfectly, except that the actions did not quite fit him. He wanted to shake Ngoza’s hand, he could not sustain the look of indifference for long, and in the end he spoke directly to him, in benediction, as he left, “hamba kahle—walk pleasantly,” to which Ngoza replied, “tsala kahle—sit pleasantly.”23

After his initial reconnaissance tour of Natal, Colenso returned to England to gather his mission party. In May of 1855, Bishop John William Colenso returned to his new home. He made his way to Pietermaritzburg and then to Bishopstowe, where his historic tenure officially began. The colony held about six thousand whites and over one hundred thousand Africans. Given that the colony had two major cities, the port city of Durban and, fifty miles away, Pietermaritzburg, the seat of the government, and comprised thousands of square miles, the bishop had his work cut out for him. At Bishopstowe, Colenso began his ambitious project to establish the mission station, Ekukhanyeni (meaning the Place or Home of Light or Enlightenment). He envisioned that Ekukhanyeni would impart the best of European civilization. It would offer training in agriculture and mechanics, which would form farmers and artisans with skills vital to the colony. It would teach reading and writing and cultivate intellectual excellence.24

It was no accident that Bishopstowe stood in the shadow of the magnificent Table Mountain. John and Frances Colenso fell deeply in love with the area, the view of the mountain, the slopes and hills of the land, the sounds of the land, and the breathtaking beauty of its sunrises and sunsets. The beauty and power of Bishopstowe and the view of the mountain, which Frances called “that majestic altar,” centered Colenso’s dreams and work.25 Also central to the bishop’s dreams and work was the translation of the Bible into the language of the people. To this he turned considerable energy. One of the first structures erected at Bishopstowe was a hexagonal summer house, which was lined inside with bookshelves. There Colenso would sit with his native informants, that is, his language teachers, and do the difficult, painstaking work of learning the language and translating. The bishop carried on a full slate of pastoral duties: teaching, preaching every Sunday, visiting, church administration, missionary fundraising, and looking for and cultivating priests. But he understood the center of his mission to be translation.

Colenso strongly believed that the gospel must be preached and presented to the natives in their own language. This was the hallmark of the Protestant Reformation and the central energy behind the translation endeavor of every Protestant mission. Ministry must be in the vernacular of the common people. Everything revolved around understanding native words and presenting a Christian world in those words. Colenso’s insight was far deeper than he realized. Indeed, his intuition was going to place him in unimaginable difficulty and unanticipated suffering. Yet his work of translation exposed an unbroken thread that tied his life together, from his early days as the principal caretaker of his younger siblings, through his years of struggle at Cambridge, to the summer house: unrelenting hard work.26

Showing frustration with those who did not understand the hard work, necessary patience, and great urgency of translating, Colenso wrote, “I have no special gift for languages, but what is shared by most educated men of fair ability. What I have done, I have done by hard work—by sitting with my natives day after day …—conversing with them as well as I could, and listening to them conversing,—writing down what I could of their talk from their own lips…. [P]icture to yourself what it is to have the whole Diocese waiting for books in the Native Language, which I must personally not only make and write, but make as correct as possible in the minutest detail, and be as careful to the printing as I must to the writing, (to say nothing of the cares of a household of some 70 souls).”27 Colenso gained through struggle what Shepstone had through birth, namely, access to the everyday speech of the native peoples. Colenso also gained access to a space in which his nascent theological vision would encounter the thoughts and hopes, the pain and suffering of Africans. This was a place where the possibilities of “resistance and new consciousness may emerge.”28 It was also a place where the subterranean cracks in his synthesis of the British colonial project, his theological vision, his ecclesial identity and commitments, and his commitment to the implementation of Shepstone’s colonial system began to show.

As he began his work of translation, Colenso was still greatly enamored of Shepstone’s vision of managing African flesh. He was wholly convinced that Shepstone’s pipe dream of setting up an African colony in Zululand with himself as chief and Colenso as spiritual director was an urgently needed plan of action to address the “overcrowding” of Natal with native refugees. This “black kingdom” would be a model city displaying the civilizing and Christianizing effects of careful planning and engineering of native lives.29 If the massive contradictions in the Shepstone system were concealed to Colenso when he began his translation work, it is because his mind was preoccupied with the theological revolution that was forming in his thinking. As he shared space with black bodies, space born in speaking and listening, the theological seeds planted by Coleridge and Maurice began to grow and take new shape. Fully a man of his time, he was also in many ways ahead of his time.

Colenso’s time was not a great one for Christian missions in southern Africa. Most missionaries in the colony were moving inextricably toward supporting full-blown British imperialism and the stark segregation of the races. Such movement was due to the fact that few denominations were having overwhelming success in converting large numbers of natives. Most mission stations were modest affairs, and the people who usually came to and inhabited mission stations were the outcasts of African societies—homeless, displaced natives and those seeking refuge from chiefs or clans. Mission stations stood between worlds—Christian and non-Christian, European and African—and created tensions between those worlds. Those Africans who became ikholwa or kholw, Christian converts, were caught between two worlds.

These Christians converts were estranged from and resisted by both worlds, but especially by the white settler world, which saw them as one of their greatest threats. They represented the success of strategies of Western domesticity. Increasingly educated, economically able and savvy, socially and politically ambitious, the kholwa represented the possibility of full inclusion, biracial community, and equality. For the many chiefs within the Shepstone system, the kholwa presented subversive elements, people who resisted the old ways, especially the authority of chiefs to guide their lives. By whites, they were denied full citizenship in the colony, especially the right to vote and freedom from the jurisdiction and demands of chiefdoms. By blacks, they were shunned, ostracized, and held in suspicion.30 The kholwa consequently failed to prosper in the colonial world of Natal, their lives witnessing a system set to deny the very thing it claimed to promote: Christian civilization. If the kholwa exposed the deepest contradiction of the colonialist Christian vision, it was not a contradiction that factored into the missional or pedagogical vision of Bishop Colenso.

For Colenso, Ekukhanyeni was a place of vision. He approached his Zulu students as people who were to be prepared to lead their nation and participate in a universal human society. Drawn to this school were John and William Ngidi and Magema Magwaza Fuze. John and William Ngidi had been converted by an American missionary who employed them as assistants. When that missionary died, John and William looked for new employment and came to Colenso and Ekukhanyeni. William Ngidi and Magema Fuze became Bishop Colenso’s primary assistants, but the term assistant does not capture the impact of their lives on Colenso. He enlisted them as conversation partners who not only were learning how to read and write in both English and isiZulu but who were also publishing their own work.

Bishop Colenso began the education of Africans on a footing that was unprecedented. On a trip to visit the Zulu king, Mpande, Colenso encouraged the students who were accompanying him—Magema Fuze, Ndiane Ngubane, and now assistant teacher William Ngidi—to keep journals of the visitation. Those journals, published in 1860 as Three Native Accounts of the Visit of the Bishop of Natal in September and October, 1859, to Umpande, King of the Zulus, were among the first English/isiZulu texts written by natives.31 Another important text published at Ekukhanyeni was Magema Fuze’s Abantu Abamnyama, Lapa Bavela Ngakona (The Black People and Whence They Came), considered the first book written by a Zulu in his native dialect.32 These fruits of mission labor are crucial because they indicate that the trajectory Colenso’s Africans students were on was toward self-articulation.

Colenso granted the students access to a workbench in the building of European discursive operations, to the literary weapons of warfare and defense, to the tools for engaging in emancipatory politics, and to the building blocks of nationalist existence. Indeed, Colenso could be appropriately construed as the spiritual father of a particular moment and region of African literary consciousness. However, all his efforts were under the canopy of preparing proper colonial subjects. The central plan shaping the educational mission of Ekukhanyeni was Shepstonian in nature. Shepstone convinced him that success at the mission required a top-down approach, which meant that Colenso would seek to educate the first sons (and a few daughters) of chiefs. The philosophy was straightforward: where the British-educated head goes, the native bodies will follow. British education, in the hands of Colenso and Shepstone in these early years, never lost sight of this hegemonic overlay.

Colenso’s missionary vision, however, led him into the ecclesial tensions and theological conflicts that ultimately defined his life. The historic struggles among Bishop Colenso, Metropolitan Robert Gray (bishop of Cape Town), and the Anglican Church, which led to charges of heresy against Colenso and his excommunication, have been well documented, and their complex details need not be recited here.33 However, of crucial import is the theological vision that surfaced through Colenso’s work and his historic struggle for his ecclesial-professional life. For it is precisely that theological vision, along with the full development of the white supremacist state, that destroyed the spectacular trajectory of the Bishopstowe mission station. That theological vision also exposes much of the conceptual architecture of modern-day white, Western theological engagements with non-Western Christians. Equally important, Colenso’s reflections show the ambiguous inner logic of strategies of contextuality. With Colenso one gains a vision strongly rooted in the European Enlightenment, in frustrations with industrial capitalism, and in the exhaustion of an orthodox imagination. Together they created in Colenso a flight to the universal, a flight that illumines both the great riches and tragic dimensions of his theology. Yet most centrally, Bishop Colenso’s thought reveals the deeply contorted ground on which translation of the Christian world had been forced to proceed.

It would be difficult to find a more productive Christian intellectual in the mission field than John William Colenso. His translation output was simply breathtaking. Less than three months after his mission party’s arrival, he produced a massive Zulu dictionary, a Zulu grammar, and a revised Zulu version of the Gospel of St. Matthew. By the end of his first seven years in Natal, he would add the entire New Testament, Genesis, Exodus, and Samuel, all translated into isiZulu. He would also publish a Zulu liturgy, a treatise on the Decalogue, and Zulu readers in astronomy, geography, geology, and history.34 This list does not include the other publications Colenso oversaw through the operation of the station’s printing press. By his side, along with other assistants, was William Ngidi, constantly asking questions, probing Colenso’s theological responses, and suggesting alternative readings and interpretations. In this context one can see both the maturation and alteration of his theology since his arrival in Natal and entry into the everyday practices of translation and mission work. At the heart of that thinking was his commentary on Romans, entitled St. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans: Newly Translated, and Explained from a Missionary Point of View, published at Bishopstowe in June of 1861 and republished in 1863.35

The commentary on Romans, not his more famous and more widely disseminated work The Pentateuch and the Book of Joshua: Critically Examined, led to the charges of heresy brought against Colenso.36 In fact, the text on the Pentateuch only enacts a portion of the theological agenda outlined in the Romans commentary. In writing a Romans commentary, Colenso stands in a historical line of theologians that extends before him to Luther and after him to Karl Barth. Like them, Colenso was compelled to return to the text that elaborates the foundations of the Christian life in order to reestablish Christian existence in this new world, not only the British world but the world of Natal. As Andrew Walls notes, the book of Romans, especially Rom 1 and 2, has played a crucial role in the theological imaginations of missionaries. The Romans epistle was their strongest ally as they sought to articulate a theological vision of their efforts. Missionaries saw in Romans 1 a corrective to Christian arrogance.37

If, as Colenso believed, “the great work of the Christian Teacher of to-day is to translate the language of the devout men of former ages into that of our own,” then he understood his commentary work to read the fundamental aspects of faith from the standpoint of the missionary situation and thereby articulate more precisely the very nature of Christianity.38 Colenso’s commentary comes in the midst of two historic developments. First, he writes within the continuation of the comparativist hermeneutic that we have seen modeled in Acosta. That hermeneutic drew historical and immediate comparison between Christianity and other religions. In contrast to that of the Renaissance Catholic Acosta, Colenso’s work stands in the midst of the modern Protestant recapitulation of that theological operation. That is, Colenso’s thinking reflects the new conceptual arrangement of being able to compare the religious practices of different indigenes from multiple colonialist sites by analyzing side by side the different native religious subjects and their different religious systems. However, in Colenso’s time comparative procedures were being decoupled from their theological moorings and were in effect reinventing the religions of the world through racial and cultural taxonomies.39 This meant that by Colenso’s time native religions were increasingly read outside of such Christian theological frameworks as, for example, manifestations of the demonic. Rather, native religions were read as affirmations of racial character and indicators of civilization and human development.

The modern invention of religion again is, first, a reinvention of the trajectory taken by the Portuguese and the Spanish, who, as we have seen, first drew up the possibilities of (theological) anthropological reflection through descriptions of body differences (for example, skin color, hair texture, manner of dress, and so forth). The need to explain unforeseen, exotic peoples invoked through descriptive practices new ways of creating knowledge. The same questions regarding the status of a religious consciousness among the natives who were present with Acosta and his colleagues were also at work in Colenso’s epoch. That is, these questions grew out of descriptive procedures that bound assessment of religious consciousness to the assessment of the body. It had been argued in Colenso’s time that the tribes of southern Africa lacked religion because they were developmentally deficient. As David Chidester notes in Savage Systems: Colonialism and Comparative Religion in Southern Africa, the comparativist strategy was calibrated to the desire for land accumulation: “Such total denial [of African religions] was a comparative strategy particularly suited for the conditions of a contested frontier. On the battlefield, the enemy had no religion. At the front lines of a contest of religions, Christian missionaries adopted this strategy of denial. However, denial was also a strategy that suited the interests of European settlers who during the 1820s and 1830s had increasingly established their presence, and their claims on land, in the Eastern Cape. In addition to missionary accounts, therefore, the frontier also produced settler theories of religion.”40

Such logic is not new. From the beginning of the age of discovery, Europeans perceived Africans as having the most bestial, debased forms of religious practice. Colenso’s time also saw the continuation of another aspect of the vision of deficient black religion: that lack of religion was bound to a lack of any inherent claim on the land. The designation of native religious practices as superstition rather than religion became an important discursive practice within this stratagem of denial. But the stratagem fell out of direct use in Natal at the time of the Shepstone system. With the land safely in the hands of the colonialists, “the Zulu lost political autonomy but gained the recognition by Europeans commentators that they had an indigenous religious system.”41 Such recognition resulted from the growing awareness that earlier assessments of the religious status of the Zulu were fundamentally incorrect as well as from the fact that such an acknowledgment had no effect on the seizing and transformation of the land. Thus, religion became a signifier within the loss of land control. Religion as a signifier for African identity grew in direct proportion to African alienation from their land, so that by the beginning of the twentieth century African life in Natal reflected a long history of geographic displacement and loss.42

These spatial dimensions are subtextual in Colenso’s commentaries and an important, albeit unrealized, aspect of his critique of the arrogance of the settlers and missionaries. Colenso will draw Zulu religious practice into a positive theological vision. This in and of itself is a powerful and revolutionary act given the prevailing missionary and theological sentiments of his day. Yet he will operate within the emerging ideological use of religion and African religious consciousness displaced from specific claims on space and place. Equally important, Colenso’s theological vision will form yet another strategy of land displacement. This is not to say that Colenso and his European colleagues failed to see Africans’ connection to the land. They simply dismissed that connection as nonessential except in the most basic form of use-value.

The other historic development that intersects with Colenso’s commentary work is the advent of what Jonathan Sheehan has termed the Enlightenment Bible.43 By this Sheehan refers to the transformation of the Bible in modernity through “a complex set of practices whose most sophisticated instruments were scholarship—philological, literary, and historical—and translation.”44 Sheehan’s insightful reading of this history accurately lodges its beginning in the Protestant Reformation (as well as the Renaissance and scientific revolution). Protestantism was from its beginning a movement shaped by the desire for a vernacular Bible in the hands of the people, the Reformation motto of sola scriptura capturing Protestants’ hopes to restore the Bible to its central place in understanding divine authority. As Sheehan notes, however, “If Protestant vernacular translation bridged the gap, once again, between heaven and earth, it also revealed the very human side of the biblical text that the doctrine of sola scriptura could never admit.”45 Protestants encountered the real dilemma of articulating the divine authority of Scripture without the benefit of a magisterium or a canonical process vivified by ecclesial oversight or the proliferation of vernacular translation checked by any overarching priestly authority. The reformers, Sheehan argues, established “a new vernacular biblical canon” as a way to stabilize the authoritative texts and lodge Christian tradition into a single text, the Bible itself, but this process also gave birth to the “tools of biblical decanonization.”46 Thus the “sixteenth-century vernacular Bible represented…both a successful break with tradition and a successful consolidation of a new tradition.”47

That new tradition as it was articulated especially in Germany and England would give rise on the one hand to an explosion of textual scholarship and on the other hand to “the vernacular translation project.”48 As Sheehan notes, both of these endeavors would move the Bible beyond theology. Biblical scholars and translators (often one and the same) perceived theology (here understood as doctrinally disciplined and traditioned reflection on Scripture) as nonessential commentary on the Bible. Sheehan is not suggesting that this development is antitheological in its inception; rather, it established a steady and fundamental distancing from theology.49 Sheehan’s account of the complex, rich history of Reformation and post-Reformation biblical development is sparse but effective. His central point is crucial: “If the Bible had always functioned in Christian Europe as an essentially unified text—indeed, its theological importance depended on this unity—the post-theological Enlightenment Bible would build its authority across a diverse set of domains and disciplines. Its authority had no essential center, but instead coalesced around four fundamental nuclei. Philology, pedagogy, poetry, and history: each offered its own answer to the question of biblical authority, answers that were given literary form in the guise of new translations.”50

The Enlightenment Bible comprised four emanations. The textual emanation, the Bible understood as a set of documents, allowed philological investigation to circumvent theological questions and controversies by cultivating textual criticism. Textual criticism inserted and consequently hid (theological) commentary inside the criticism itself, within the marginalia of textual display, apparatus, and translation. The pedagogical emanation presented the Bible as a distillation of moral truths. The pedagogical Bible instilled a timeless moral vision for all humanity. It was this vision of a morally compelling thrust at the hermeneutic center of the Bible (as well as of other crucial texts) that fueled nineteenth-century romanticism. The poetic emanation viewed the Bible through the lens of the historical and timeless reality of poetic expression that is present among every people. The poetic Bible exhibited the literary heritage of humanity and revealed the Bible’s complete translatability, which makes possible its utter rebirth into diverse national literatures.51 The historical emanation drove the Bible deeply within the historiographic imagination, and it issued as a historical archive. As archive, the Bible became “an infinitely variegated library of human customs and origins. And in this historical Bible, the ideal of a familiar text was abandoned for one perpetually in [historical] translation.”52 The historical Bible was a powerful emanation of Enlightenment mentality in its ability to police theology by enfolding theological reflection with the Bible itself into a broader search for common human imaginings and knowledge.

These Enlightenment emanations converge and coalesce around what Sheehan calls the cultural Bible. In Germany and England, the cultural Bible becomes the sacred text of a nation and a people. The cultural Bible is fruitful for the cultivation of society and the formation of civilization; the Bible becomes, especially in Germany, the Ur-text of civilization. Central to the creation of a cultural Bible was the dismissal of Judaism and Jewish people from any claim, not only to the Bible, but to any cultural heritage which might undermine the articulation of the Bible as Christian literature. The presence of Jewish people was hermeneutically sealed off from the vision of the Bible as a national treasure, as the cultural expression of the national spirit, and, in the case of Germany, the German soul.

There was great fear in England over the transformation of the Bible into the Enlightenment Bible. As Sheehan puts it, “English theologians and critics abandoned the thorny paths of historical criticism for the smooth highways of orthodoxy.”53 Yet the transformation was happening with the increasing intellectual concourse between Germany and England. The publication in 1860 of Essays and Reviews (one year before Colenso published his Romans commentary), a collection of seven essays, six of which were written by Anglican churchmen, acknowledged the demand for a new Enlightenment vision of the Bible.54 That demand also presented the Bible as foundational to civilization; that is to say, the Bible emerged in England, as in Germany, as culture-constituting. The idea of culture evolved as an abstraction and as an absolute.55 As Raymond Williams notes in his powerful account of the development of the idea in England in the nineteenth century, the idea of culture was turned against the dehumanizing effects of the Industrial Revolution.56 This is not the idea of culture as it will be articulated within the social sciences and modern anthropology and ethnography, that is, as a descriptor of particular ways of life, rooted in language, rituals, and everyday practices. Rather, this is a vision of culture which captures the humanizing, spiritual essence of a people; here “culture represented that ‘heritage of an accumulated ineluctable racial memory’ that undergirded the essential qualities of ‘western civilization.’”57

The Bible thus emerged in England in Colenso’s time as the epicenter of two points of crisis and conflict. On the one hand, the Bible stood between the forces of Enlightenment change and a recalcitrant and fearful orthodoxy. On the other hand, the Bible stood between unrelenting forces of societal change bound to the Industrial Revolution and capitalism and the romanticist voices pressing for cultivation of the cultural and national spirit of a people in order to assert or reestablish as an imaginative act its moral center. The Industrial Revolution was reducing human beings to elements in the mechanization and routinization of processes of production. The romantic impulse responded to these reductive processes by proclaiming the infinite worth of the human spirit and the need to attend to exaltation through education. A third point of crisis and conflict, though lacking the Bible as its epicenter, informs Colenso’s life and work: the conflict between low church and high church, between a Protestantism pushing further away from its Roman Catholic past and a Protestantism that was retrieving a catholic identity rooted in Christian antiquity and turned toward the formation of a national church. Colenso for his part thought near the epicenter of these points of crisis and conflict. He was an evangelical Pietist who became a centrist Anglican bishop influenced by intellectual figures deeply implicated in his country’s Enlightenment movement. He was in many ways an expression of the Enlightenment Bible; yet Colenso was unable to grasp the dangers of thinking near this epicenter.

Sheehan’s account does not map cleanly onto Colenso because Colenso carries forward a genuinely theological agenda, though that theology exists under strained conditions articulated through the Enlightenment Bible. One must, however, hold together the Enlightenment markings of Colenso’s scholarship and his normalization of the spatial disruptions of Africans in his thought. The transformation of the Bible and the transformation of space play against each other in his thought. Neither becomes an articulated theme, yet each enables the other. Together they display the modern abandonment of place-centered identity, an abandonment rooted in a particular theological vision. Colenso offers a highly refined vision of the whiteness hermeneutic, the interpretative practice of dislodging particular identities from particular places by means of a soteriological vision that discerns all people on the horizon of theological identities. This discernment in and of itself is not the problem. The problem is the racialization of that soteriological vision such that racial existence is enfolded inside the displacement operation and emerges as a parasite on theological identity. But here that hermeneutic is in service, he believes, to the greater good of the African and the integrity of the mission church.

Colenso’s commentary opens quite tellingly with heartfelt dedicatory thanks to Shepstone. Colenso conversed with Shepstone about the very ideas he works out in the commentary. In fact, Colenso hoped a commentary on Romans written from the perspective of “some questions, which daily arise in Missionary labours among the heathen” would serve as the theological foundation for the great work Shepstone planned in Zululand.58 The Zululand project, as noted, was Shepstone’s plan to move tens of thousands of so-called surplus Africans from Natal to another place, where he would reside as their chief. Colenso’s commentary on Romans would serve as a kind of theological charter for the governmental operations in this new site. Even as he wrote his commentary, he was still convinced of the symmetry between his work and Shepstone’s efforts at “advancing the civilisation of [native] tribes” of the colony.59 He would match his theological reflections to Shepstone’s God-given ability “for influencing the native mind.”60 He envisioned that they would together create a humane, Christianized domesticity for the Africans. In this way, Colenso joins theological work to the advancement of civilization. He was, however, unaware that the theological vision outlined in his commentary would be at great odds with both that civilizing vision and the Shepstone system.

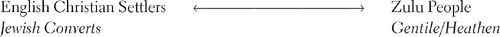

Colenso’s Romans commentary is in some ways a conventional nineteenth-century work. He situates the text in its historical setting, and, as a New Testament scholar would, he posits the identity of the audience for the epistle and then displays his evidence for his contention. Colenso understood the letter to be written to Jewish believers. But unlike conventional New Testament scholars, Colenso has a more pivotal concern in mind than establishing Paul’s audience when he posits Jewish believers as the central addressees in Romans. The Jews in the text stand in for arrogant English Christian settlers in the new world of Africa. The Zulu, by contrast, do not simply stand in for the Gentile/heathen; they are in fact the Gentile/heathen. In schematic form his analogy would look like this:

Colenso is not engaged in straightforward anti-Semitism in his commentary, although he does have a very denigrating vision of Jewish identity.61 What he puts forward is much more complex than a simple derogatory deployment of biblical Jewish identity. Colenso is reading salvation history inside settler-Zulu relations and attempting to render the particularities of identity inconsequential to Christian existence. In order to do this, Colenso must racialize those identities to then transcend them. Key to this interpretive move is the slow construction of the divine character based on his reading of Romans in such a way as to make Jewish particularity of no importance to God. Indeed, God will quickly appear in Colenso’s commentary as being fundamentally opposed to Jewish priority and election. God is ultimately opposed to that priority because God takes no stock in particular (racial) Jewish identity. In this regard, Colenso suggests Nicodemus as a Jewish archetype:

Nicodemus also had no doubt as to his own right, not merely as a true believer in God, but as a true born Jew, a child of Abraham, to have a share in it. What he wanted to know was…how he might best attain a worthy place in that kingdom…. Our Lord throws him back at once in His reply to the only true ground of hope. It is as if He had said,…“You are come to me very confident of your concern in this Kingdom. You are sure, you think, of a place in it. But why are you sure? What ground have you for thinking that you have any place at all in it? Do you imagine that, because you are born of Abraham, your claim will be allowed? But I tell you this will avail you for nothing. Your mere natural descent is no ground at all for any such expectation…. This, then, was an instance of a devout Jew, fully prepossessed with the infatuation of his people, and requiring to have this false ground of hope struck away from under his feet at the very outset, if he would heartily embrace the faith of Jesus.62

Colenso imagines the conversation between Nicodemus and Jesus as a deconstructive one. Jesus removes from Nicodemus any presumption of divine privilege, any connection of divine life with particular human flesh. This statement as an implicit critique of English settler mentality would be a powerful word against that form of Christian hegemony. But it already exposes the problematic equation of white (English) Christian with Jew. That equation demands a deep commitment to a moment of transition, a supersessionism that enables the analogy itself. The transition for Colenso allows one to move from an ethnocentrism to a theocentrism, from imperfect Christian doctrine yet trapped in “Jewish sentiments” to the true spirit of the gospel. That spirit is a universal spirit. Colenso’s first major hermeneutic move is to place all peoples under the fundamental problem, ethnocentrism. The Jews of Paul’s day, like the Romans and Greeks before them, like the settlers and the Zulu, all read the world as being composed of one people with the rest of the world as “foreigners, men of the nations” (for example, Jews and Gentiles, Greeks and barbarians).63

It is precisely this assumed racial supremacy of a people that is “a worm lying at the root of all [the] Christian profession” of so many pious believers in Rome.64 For Colenso, Israel reveals this original mistake. One finds three primary errors in Jewish believers in Rome: birth, messianic expectation, and law. He writes,

1. The Jew said, “I am a favoured creature—a child of Abraham, and therefore a child of God, and an heir of His kingdom, whatever my life may be. What have I to do with a message of salvation? Perhaps, for the heathen it may be needed. But the Kingdom of God is mine, by virtue of the promise made to my great forefather. I have a right to enter it. I claim it as mine.” This error St. Paul must correct by showing that he had no such right, that he, the Jew, needed the free gift of Righteousness, as well as all others of the human race—that he too was “concluded under sin” like others, and had no claim whatever, because of God’s promises to Abraham….65

2. But the Jew might say, “Suppose that I admit this, yet, at all events, the Messiah is to come specially for us. He is to be the carrying out and realization of those promises to our forefathers, which made us the favoured people above others. You do not surely mean to say that we, Jews, the children of Abraham, the chosen family of God, are to be put on an equality with the common Gentile in this respect?” “Yes!” St. Paul would say, “you are to be put on a perfect equality with the meanest Gentile. You will stand no better than they in this respect—not a whit more safe from God’s wrath—not a whit more sure of entering the Kingdom….

3. Still, however, the Jew might persevere and say: “But surely our Law is not to be done way with. At all events, the Gentiles, if they are to partake of the Gospel, and even to be admitted to share on equal terms with us, must conform to our religion, and practise those observances, which have come down to us through fifteen hundred years on the authority of Moses, with the Divine Seal upon them….” “No!” says the Apostle again, “Faith, simple faith, a true, living, childlike faith and trust, that worketh by love, this is all that God seeks of all—no circumcision—no Jewish practices or peculiarities…. These are all now done away in Christ Jesus.

These theological points not only reflect nineteenth-century Protestant theology but also in essence reflect some of the strongest interpretive tendencies in Christian accounts of Israel’s identity in relation to Christian identity. Colenso’s Paul negates any soteriological character to Jewish identity. This also means that messianic expectations geared to the concrete salvation of their people are also meaningless. Israel loses any historic trajectory of liberation, any political hope born in the past that should shape the present. In addition, the negation of the law means that their salvific future requires them to abandon the very practices that have defined them. Colenso thus offered up through his reading of the early chapters of Romans a Jewish people that has nothing of saving importance to offer the world of the Gentiles. They are quite literally the foil to faith, the carrier pigeon of the gospel. Moreover, any attempt to offer anything of particular communal or “racial” substance to the Gentiles that would be in any way binding on the Gentiles would be an exercise in sinful futility. This, according to Colenso, is the heart of Paul’s critique of his Jewish family.

The analogy with the settlers breaks down rather quickly at this point. Unlike Colenso’s Roman Jews, English settlers did indeed believe they had something of saving importance to offer the heathen, even if Colenso’s exegetical reflections denied that belief. Indeed Colenso’s own vision of civilization grants to Britannia what he refuses Israel, namely, the refashioning of a people’s way of life for theological reasons.

The entire commentary builds from this logic and this massive blind spot, but the heart of Colenso’s Romans commentary, the central image he powerfully develops, is that of God the loving and merciful father. In his use of this brilliant image lie both the riches and the poverty of Colenso’s theological vision. If Israel serves any purpose, it is to expose to humankind the God who loves them. Colenso’s twist on the “righteousness of God” exemplifies how a specific history within which righteousness becomes intelligible disappears and becomes a universal sense of divine righteousness: “This ‘righteousness of God,’—this righteousness which comes from God—which is the free gift of God—which…God has given to the whole human race, before and after the coming of Christ,—is being ‘revealed,’ he says, that is, unveiled, in the Gospel. It is there already, in the mind of our Faithful Creator, in the heart of our Loving Father. The whole human race was redeemed from the curse of the Fall, in the counsels of Almighty Wisdom, from all eternity—the Lamb was slain ‘from before the foundations of the world.’…[T]he whole family of man, in the ages gone by…were yet ‘justified,’ made just or righteous, dealt with as children, before any clear revelation was made of the way in which that righteousness was given to them.”66 Colenso here draws on an extremely powerful theological position that will be performed in countless ways by a variety of theologians in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It discerns the saving work of God as a completed act that must govern the ways one thinks about the material enactments of that accomplished work. Colenso came to this radical position from seeing its opposite in the missionary field. Colenso was painfully familiar with the theological position propounded by many missionaries that placed those who had died without Christian faith under damnation in hell and eternally punished. Colenso, in his book describing his first visit to the Natal colony, Ten Weeks in Natal, tells the story of sitting by the Tongaat River having lunch and reading in the Missionary Intelligencer something that greatly disturbed him. He had a section from the paper that an American missionary had used to wrap Colenso’s lunch. He read stories in which natives were told that everyone who dies without the gospel is burning in hell from the moment of death: “I quote these passages, not for a moment wishing it to be supposed, that the good American Missionaries of Natal hold and preach, as a body, these fearful doctrines—God forbid!—but to enter my own solemn protest against them, as utterly contrary to the whole spirit of the Gospel,—as obscuring the Grace of God, and perverting His message of Love and ‘Goodwill to man,’ and operating, with most injurious and deadening effect, both on those who teach, and on those who are taught.”67

A few years after the publication of his Romans commentary, in a speech before the Anthropological Society of London, Bishop Colenso recalled with revulsion a prayer he had seen published by a missionary institution associated with his church. The prayer included the words, “O Eternal God, Creator of all things, mercifully remember that the souls of unbelievers are the work of Thy hands, and that they are created in Thy resemblance. Behold, O Lord, how hell is filled with them, to the dishonor of Thy Holy Name.”68 Colenso rightly discerned a presumption lodged deeply in this position: the ideas of sin, damnation, and punishment are collapsed into divine enactment.

According to this skewed logic, to believe in these tenets is to also believe that they are now temporally in effect. Moreover, the strength of that belief is bound to the surety of one’s ability to discern its realities in humanity, especially in and among the Africans. While the roots of this flawed theological vision were ancient by Colenso’s day, they carry an intensely imperialist character. Essentially, it inserts humanity, and in this case Europeans, in a God-position vis-à-vis decisions of eternal significance. It draws colonialist hubris deeply inside a constellation of theological ideas. It is that hubris that triggers what would become in the late nineteenth century and twentieth a formulaic way of articulating the relation between sin, damnation, and eternal punishment. What is concealed in that formulaic articulation is the centered white subject who discerns moral deficiency, salvific absence, and the eternal state after death. Colonialism is not the cause of this theological problem but, bound to Enlightenment reconfigurations of theological knowledge, surely is its refinement.

Colenso presses against this constricted vision of salvation that says, once I see that you believe in Jesus you are saved, but if I discern disbelief or the absence of belief in you, then upon your death you will be eternally punished in hell. However, he cannot escape its imperialist presumptions. Colenso will offer up its mirror image, an image that will carry an inverted constriction:

Already, side by side with this revelation of God’s wrath for willful sin in the heart of man, there is a revelation of His Mercy—a secret sense that there is forgiveness with our Father in Heaven, in some way or other, possible or actual. The Jews, before the coming of Christ, had their system of sacrifices given them, to remind and assure them of this. The heathen had their various modes of quieting their hearts, with what served to them as a pledge of Divine forgiveness. But all men, everywhere, have had all along, and still have, a belief in such Divine Forgiveness, as well as in such Divine Wrath upon willful sin; they have a feeling that it must exist, it must somehow be provided for them. Nay, coupled with the very sense of sin, there is a dim sense of a righteousness which they already possess.69

Colenso folds all humanity into righteousness, not damnation. Central to this universal affirmation is the leveling of all peoples through their particular religious experiences. Divine righteousness enables religious ethnography, an ability to discern a theological sameness in all people. As Jonathan Draper notes, for Colenso, “God has simply provided a righteousness to the whole human race in Christ, whether they knew it and accepted it by an act of faith on their part or not…. All of us, Christians, Jews, heathen, were dealt with by Creator God as righteous creatures, not only now, but ‘from all eternity’. This was the reason for the universality of human religious experience, which impels people to live moral lives.”70 One can discern the German Idealist tradition in this method of articulating the relation of revelation to salvation. This way of grasping the religious subject enables a benign, even generous posture toward different peoples. Colenso puts the Enlightenment romanticist ideas to powerful use.

Colenso’s way of describing the religious subject, especially the Zulu, is elegant. All people operate in the moral and spiritual light they have been given. Punishment is calibrated by their moral failure or integrity in operating in their inherent sense of sin or righteousness. Christian faith is the revelation of this very fact—that is, of inherent righteousness—and the Zulus are a perfect example. As he says, “We know that they exhibit certain virtues, and are capable of brave and kind and just and generous actions. But we know also that they practise habitually, without any restraint, a certain gross form of vice, that they kill for trivial causes, sometimes, apparently, for none at all.”71 Colenso goes on to say that sin is the disregard for the light they do have. In this way Colenso, like many nineteenth-century theological figures, naturalizes Christianity, domesticating it by making Christianity the architecture of religious experience. What is also crucial is the way he does this in the colonialist mission theater.

Colenso rewrites salvation history as the history of religious consciousness. In this way he is able to name Christian arrogance and misbehavior as a great impediment to the flourishing of that religious consciousness and its possible, but not necessary, movement toward Christianity. In a passage astonishing for its level of insight, given the virulent forms of anti-Semitism of his era, Colenso recognizes that Jewish resistance to Christian faith in his day was due not to a Jewish “reprobate mind” but to Christian behavior: “It is far more likely that the acts of abominable cruelty, injustice, and contemptuous bigotry, with which, in Christian lands and by Christian people—too often, alas! by Christian ministers—they have been so frequently, and are even now, treated, have gone far to fix them in holy and righteous horror of a religion, which taught that such outrages were right. All, surely, that an humble-minded Christian can allow himself to say of the present state of the Jews generally, is that they are not actually incurring great moral guilt—(he cannot judge of that,)—but suffering great moral and spiritual loss from the acts of their forefathers.”72 Colenso makes religious consciousness the given reality within which God is already working out a drama of salvation and conversion. Romans, Jews, and other Gentiles each follow their inherent moral light and will be judged accordingly. So, too, for Zulu and settler alike God has graciously forgiven them and wants them to hear “by means of any one of Earth’s ten thousand voices” the Father’s declaration of righteousness.73 In Colenso’s hands, the message of the gospel becomes one of acceptance and awareness: acceptance of the gracious gift of God’s righteousness and awareness of God’s fatherly love, ultimately revealed in Jesus. Colenso’s theology draws a straight line from biblical Jews and Gentiles/heathen to Christian settlers and Zulu/heathen. What holds them all together in his vision is the fatherly love of the Creator God who has shed light “into their very hearts.”74 Their moral duty—white settler, Zulu, Gentile, Jew—is to move toward the inward light that is also reflected in the Son: “The Apostle does not say that God is reconciled to us by the Death of His Son, but that we are reconciled to God. The difference in the meaning of these two expressions is infinite. It is our unwillingness, fear, distrust, that is taken away by the revelation of God’s Love to us in His Son. There is nothing now to prevent our going, with the prodigal of old, and throwing ourselves at His Feet, and saying, ‘Father, I have sinned; but Thou art Love.’”75

The bishop drew on the biblical story to fill in his description of God the Father and thereby render at times an exquisite picture of divine love. But at the same time, Colenso’s vision evacuated Christian identity of any real substance. All theological identity is essentially the same, Jewish, Christian, or Zulu—an internalized struggle of the religious consciousness to hear the word of love and acceptance from God the Creator-Father and his son, Jesus, and to follow the dictates of the moral universal inherent in all people. What looks like a radical antiracist, antiethnocentric vision of Christian faith is in fact profoundly imperialist. Colenso’s universalism undermines all forms of identity except that of the colonialist.

This reading of Colenso’s theological position in his Romans commentary may seem counterintuitive. It was Colenso who, among others, reversed the idea that the Zulu had no religion and no knowledge of God. He pressed the position that among the Zulus God was known and had been called uNkulunkulu, the Great-Great One, or umVelinqangi, the Supreme Creator. Indeed, Colenso’s deep commitment to recognizing Zulu religious consciousness helped fuel Zulu cultural nationalism. Moreover, Colenso, like Shepstone, believed in building Christian civilization on top of existing native logics, such practices as cattle or property exchange as part of arranged marriages and polygamous family life. Yet in Colenso’s hands, the (religious) cultural particular says nothing productive. In fact, he already knows what is the telos of all religious consciousness. Jeff Guy summarizes Colenso’s geographic teleology:

Colenso’s role as a missionary bishop in Natal was to promote commodity production and capital accumulation through the propagation of the standards and expectations of the Christian way of life—the Christian way of life as perceived by the Victorian middle class, of course. The purpose of his mission was to produce the scrubbed, well-dressed, properly trained African family, living in a square house, separated from other households, faithful to the precepts of individualism, hard work and the Bible, the husband selling his labour, spending his income wisely, and thereby advancing the economic progress of the colony and his own social status, his wife in the home, his daughters in service, and his sons in training and preparing to marry monogamously, to reinforce and repeat the process.76