YOU MAY LOVE TO BAKE, can or cook up a storm in the kitchen. That’s a great foundation for a cottage food enterprise. But there are a few steps to go through, transitioning from being a “home cook” to being a “food entrepreneur.” This chapter examines some of your options and opportunities as a CFO, defined by the cottage food law where you live.

Cottage food laws vary a lot by state. The reason for this current patchwork of laws dates back to one of the underlying principles our country was founded upon: states’ rights. In the US, the founding fathers believed in giving independence and governing authority to the states on many issues.

The way that works today regarding food is the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) publishes the Food Code, a model for the states to base their food regulation on — all 700-plus pages of it. The Food Code provides a scientifically sound technical and legal basis for the food industry as a whole, and states generally abide by it. Another way to look at this is to think of state regulations as cars: there are lots of makes and models, but everything is pretty much the same under the hood. Because cottage food laws don’t cross state lines, only concern yourself with what’s required in your state. That’s simple enough, right?

There are four key questions you need answered in your state’s cottage food law before you get started:

• What products can you sell?

• Where can you sell your products?

• How are you allowed to sell your products?

• How much can you sell of your products?

Once you’ve answered these questions and understand how the cottage food law operates in your state, you’ll then need to figure out whether what you love to make is worth selling. If people are clamoring for your pretzels, that’s an excellent sign. In the end, your ability to sell products is based on creating items your customers want, need and are willing to buy at a fair price that they, not you, determine. That’s where marketing — covered in several chapters of this book — comes in.

Fresh-baked pretzels can be a hit, especially if you make your own high-acid mustard to go with them. JOHN D. IVANKO

![]()

“While everyone from the media to Capitol Hill keeps spinning wheels trying to find the perfect panacea for job creation, especially in rural areas, they really need to look no further than our nation’s kitchens. Our American history has roots in this idea of cottage businesses, from the butcher to the baker and other food artisans who create things at home that service their local community.”

— PATTY CANTRELL, FOUNDER OF REGIONAL FOOD SOLUTIONS LLC

![]()

Question 1: What Products Can You Sell?

There’s a reason for you to first see what types of products you can produce under your state’s cottage food law. It’s the classic glass-half-full versus glass-half-empty scenario: focus on what you can legally make and don’t waste time, energy and money spinning your wheels on what you can’t. Don’t complain, just cook.

Your state’s legislation will specifically outline those “non-hazardous” food items you can produce under cottage food law. In the simplest terms, the conventions used to define such food are low-moisture and high-acid. Sometimes the legislation will itemize what you can or can’t sell.

Non-hazardous is the key word. You don’t see that term used in recipes, right? By scientific definition, it refers to an item, usually a baked good, that has a low moisture level, measured as a water activity value of 0.85 or less. Or it can be a high-acid food, measured by an equilibrium pH value of 4.6 or lower. Some state legislation includes this exact verbiage about moisture levels and pH values. Your state may also define other non-hazardous food items you’re welcome to sell.

The two types of foods most widely approved under cottage food laws are low-moisture baked goods and high-acid canned foods like pickles or preserves, each explored next.

Baked Goods

Nearly every state that has cottage food legislation on the books includes baked goods, so this is probably the most accessible category for launching your business. Baked goods are so prevalent in cottage food legislation because it’s hard to mess up a loaf of bread or a chocolate chip cookie from a food safety perspective. Politicians, if nothing else, are mostly risk-adverse and conservative. Freshly baked, non-hazardous baked goods are in a different food “safety zone” than something like canned green beans, a low-acid canned item you’ll never see on an approved list.

A simple way to understand non-hazardous baked goods is by asking this question: Does your item require refrigeration? If, like a custard pie, it does, then you can’t sell it in nearly all states with cottage food laws.

Some common examples of items you can bake and sell to the public:

• Bread loaves

• Muffins

• Cookies

• Biscuits

• Crackers

Your items do, in fact, need to be baked to qualify as baked goods. Obvious, eh? But this also means you can’t just combine items such as rolled oats, nuts and peanut butter to make an energy bar or trail mix. Nor can you add an ingredient to something already baked, like dipping graham crackers in chocolate. Depending on your state, these types of products may be covered separately in other categories (read on!), but they wouldn’t be defined as a baked goods type product that has to meet the low moisture level requirement.

Missing from the approved non-hazardous baked goods list are any items filled with something that needs refrigeration. Moist fillings increase the moisture level and thereby increase the potential for harmful bacteria to thrive. There are a lot of variations on what a “filled” baked good can mean. Again, some states give specific guidelines while others may require you to contact the agency for clarification. A basic sugar frosting filling made with sugar, water and butter should be fine, but add in other refrigerated ingredients, such as cream cheese, and you’ll likely be out of luck.

Pumpkin bread, baked with pumpkins grown on-site. JOHN D. IVANKO

![]()

“I started my cookie business in 2008, from my home with eight hundred dollars. By my second year, I barely broke even. My business nearly quadrupled during my third year, bringing me from approximately 7 to about 28 orders per week. And last year, I averaged about 47 orders per week. Admittedly, I am an optimist, but if you had told me ten years ago that I would be able to build a cookie business from my home, doing what I am absolutely passionate about and grossing six figures into my fifth year in business, I would have certainly told you, ‘You are NUTS!’”

— AYMEE VANDYKE, ALSO KNOWN AS COOKIEPRENEUR AND OWNER OF WACKY COOKIES, VIRGINIA (WACKYCOOKIES.COM)

![]()

![]()

“There is so much untapped business opportunity to showcase each state’s baking heritage; in Wisconsin we have everything from from Swiss bratzeli cookies to Norwegian lefse to a multitude of other cultural specialties. In my work chronicling the state’s culinary legacy, I’ve meet many amazing home bakers who carry on Wisconsin food traditions. However, many of their baked goods can’t be mass produced, and therefore you can’t purchase them anywhere.”

— TERESE ALLEN, WISCONSIN’S LEADING FOOD AUTHORITY AND HISTORIAN

![]()

Low Moisture Means Baked Goods that are Safe

Don’t panic if you see a slew of technical detail and numbers in your state’s law defining non-hazardous baked goods. You don’t need to be a scientist; you do need to ensure the baked product for sale is safe by following your state’s guidelines. These definitions generally follow the FDA’s Food Code of a “water activity value of 0.85 or less.”

These definitions describe baked goods with a low moisture content, which inhibits mold growth and means they can be kept at room temperature. They’re shelf-stable. If an item is too moist, pathogens — the bad bacteria that can cause disease — grow. In such cases, these items need to be refrigerated to prevent the growth of harmful bacteria. The lower the water activity level number, the drier the food item and therefore the safer it is, because it is less prone to bacteria growth.

A state’s law may list specifically what is allowed, such as breads and cookies, and what is not, like cream pies or churros that contain a moist filling. Anything made with meat is always a definite no. What about frostings? A traditional butter cream frosting would be too moist to qualify, but some non-hazardous recipes exist that involve frosting made with a vegetable shortening base.

If you have a specific recipe you want to make and sell and are unsure where it fits on the water activity scale, your best first step is to e-mail it to the state agency administering your cottage food law. If they’re unsure, the agency may ask you to conduct an official water test, which involves sending a sample to a professional laboratory for analysis. There is no universal definition of what baked goods qualify under cottage food laws.

High-Acid Canned Goods (Preserves, Pickles and Salsa)

Second to baked goods, many cottage food laws permit high-acid canned items made in home kitchens. The “high-acid” refers to fruits and vegetables that are either naturally high in acid, such as tomatoes, or that become acidified through pickling or fermenting. To be considered high-acid, these products must have an equilibrium pH of 4.6 or less. If your memory of tenth-grade science is a bit hazy, this pH number measures acidity; the lower the number, the more acidic the food item.

Examples of high-acid canned products include:

• Jams and jellies

• Salsa

• Chutneys

• Pickled vegetables and fruits

• Sauerkraut

• Kimche

• Applesauce

Cottage food laws only refer to canned items processed with university extension-approved methods such as a hot water bath. High-acid items that don’t qualify in the legislation are refrigerator pickles or pickles made in a crock. Again, for the purposes of nearly all cottage food laws, if your product requires refrigeration, you can’t sell it.

Unlike water activity level, pH can be measured at home if permitted by your state. You can use a pH meter, which needs to be properly calibrated on the day it is used. More common are paper pH test strips, also known as litmus paper; you simply dip these in a sample jar, and the color will turn based on the acidity level and related pH number. Paper strips work best if a product has a pH of 4.0 or less; the strip’s range should go up to a pH of 4.6. Depending on your state’s rules, you may need to do a pH test on each batch or over a state-defined time frame. While more pricey, a pH meter can provide a more exacting measurement of acidity.

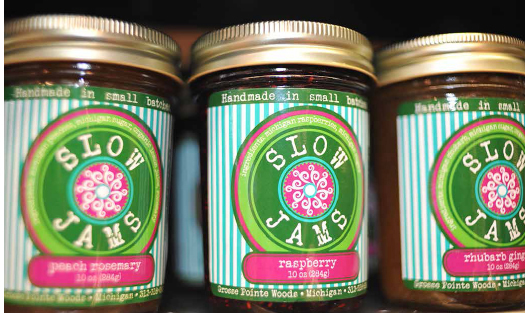

Jars of Slow Jams jam (facebook.com/slowjamsjam), handcrafted and featuring Michigan produce and sugar. Based in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, the business was originally started under cottage food legislation by Shannon Byrne. JOHN D. IVANKO

Canning and creating high-acid products are very different processes than baking. Canned items, whether high-acid or not, are more science than culinary art. While you can alter, experiment with and personalize your biscotti recipe until it is uniquely your own, this isn’t the case with canning recipes. At best, you’ll be able to adjust your spices and ratios of vegetables.

There are plenty of university extension-sanctioned recipes that have been thoroughly tested, from classic items like basic strawberry jam to more modern delicacies such as garden chutney and sweet pepper relish. Some states allow specific canning recipes from sources like the current edition of the Ball Blue Book Guide to Preserving. But note that just because a recipe is in a canning cookbook doesn’t mean it will qualify under the state law. Just follow the state-mandated recipes and protocol, and you’re good to go.

What if you want to use your great-grandma’s special family recipe for blackberry preserves? Some states will allow you to alter and create your own recipes after you complete the Master Food Preserver course. This is similar in format to the Master Gardeners program, also through university extension. There seems to be a revival with this new home-canning movement. The Master Food Preserver is a one-day intensive class that goes into the nitty-gritty science of pH and food safety procedures. Like the Master Gardeners, once you complete it, you can serve as a community education resource for local folks with canning questions.

Building Your High-Acid Knowledge Base

While home canning goes back generations, remember it’s a traditional art that has become safer over time thanks to our increasing scientific understanding of the process. Great-grandma’s tomato sauce recipe based on yesterday’s practices — which often did not include adequate water bath times or sanitation procedures — could potentially do more harm than good. So stick with current recipes from reliable and state-approved sources.

Another reason to steer clear of old recipes: some of the vegetables used today have changed in composition. Garden tomatoes, for example, have been bred to become less acidic to appease our taste preferences, a change that could significantly alter the results of the canning process and, therefore, the safety of grandma’s original recipe.

So go through a reputable source for high-acid canned recipes, such as:

• Ball Blue Book Guide to Preserving, by Alltrista Consumer Products (current edition)

• Ball Complete Book of Home Preserving, edited by Judi Kingry and Lauren Devine (current edition)

• Cooperative Extension Offices in US: csrees.usda. gov/extension

• Home Food Preservation from Penn State University: foodsafety.psu.edu/preserve.html

• National Center for Home Food Preservation: nchfp. uga.edu

• The National Center for Home Food Preservation offers a free, self-paced online course, “Preserving Food at Home: A Self-Study,” for those who want to learn more about home canning.

Name: Erin Schneider and Rob McClure

Business: Hilltop Community Farm (LaValle, Wisconsin)

Website: hilltopcommunityfarm.org

Products: sweet pickle relish, salsa and jam made with farm-grown produce

Sales venues: winter holiday market, community supported agriculture (CSA) shares, member sales

Annual sales: $2,000

Erin Schneider in front of her farm stand that features her jam, salsa, sweet pickle relish made from her farm-grown produce. COURTESY OF HILLTOP COMMUNITY FARM

Beginning Farmer Pickles Profits

Dedicated to growing food sustainably and building community, Erin Schneider and her husband, Rob McClure, own Hilltop Community Farm, a small-scale diversified community supported agriculture (CSA) farm and orchard in LaValle, Wisconsin. Exemplifying how beginning farmers can use cottage food laws, they’ve increased and diversified their farm income one home-filled canning jar at a time.

“Thanks to our state’s cottage food law covering high-acid foods, I was able to quickly and easily increase and diversify my farm income stream,” explains Schneider. We generate more than two thousand dollars annually by selling sweet pickle relish, salsas and jams at local farmers’ markets and community events.”

Not only did Schneider increase her farm income, these value-added goods showcase the farm’s fruits and vegetables in new ways and put any surplus to profitable use. “Every farmer or gardener ends up with a lot of extra something at the end of a harvest,” Schneider laments. “You could give it away or add it to the compost pile. Why not make some extra money off the labor you already invested?”

Schneider focuses on recipes that showcase their farm’s bounty and specialty items, such as jam made from black and red currants. Along with classic pickle recipes — dill, bread and butter and relish — she makes tomato-based red salsa and salsa verde, a green sauce made with tomatillos, all appealing to the spicy crowd. The jars retail between five dollars for a four-ounce jam jar to eight dollars for a pickle quart, with volume discounts of 5 percent off purchases over thirty dollars.

Schneider has two primary sales outlets:

• Direct orders from CSA members Hilltop Community Farm gives their CSA members an order form for her relish, salsas and jams so they can stock up and easily add it to their weekly delivery.

“Producing and selling these canned goods is a win-win for us: we have an added income source that keeps us diversified, and it helps support our bigger mission of helping our members and community eat seasonally year-round.”

• Winter holiday market

Schneider and McClure attend one key holiday market to sell their canned items, the Fair Trade Holiday Festival each December in Madison, Wisconsin. The gathering attracts an affluent, gift-giving crowd supportive of local agriculture. Best of all: it’s the holidays and everyone comes wanting to shop and spend.

“It’s a super busy day, but this is a prime sales venue for us where we usually sell over 120 jars and can gross over six hundred dollars at one market. The folks coming are perfectly on-target for buying what we’re making.” Booth fees for these types of venues range from fifty to a hundred dollars.

Erin Schneider selling at the Fair Trade Holiday Festival in Madison, Wisconsin. COURTESY OF HILLTOP COMMUNITY FARM

“Bundling similar items together as a suggested gift package helps move sales,” recommends Schneider. She groups similar pickled items as a “spicy sampler” and clusters the colors of the jars together on the display table in ways that place complementary colors alongside each other.

Schneider discovered that sampling plays a key role in closing the sale and garnering a premium price for her products, especially for some of her more unusual fruits like currants. “If people can taste something, I find they will spend up to two dollars more per jar because they feel confident in what they buy.” Her recipes come from family classics like her grandma’s relish, making sure all the pH levels and processing procedures are accurate by today’s modern standards.

Such high-acid canned food ventures come with a distinct seasonal work schedule: lots of processing time during peak summer, especially if you grow and harvest your own fruits and vegetables, but then your labor completely ends and you only need to sell your inventory. Schneider advises beginning business start-ups to practice recipes in small batches until they perfect their canning technique.

“It takes us about one day a week from about mid-July through September to process our lines of canned products. This can add up to some long summer days,” Schneider explains. “It takes two to four hours to harvest the produce. Then we’ll crank in the kitchen for about six hours at night.” An organized kitchen helps tremendously, developing a system for organizing and sterilizing all their equipment.

“There’s always a couple of weeks of summer harvest overload when we need to get things processed right away, but a perk is quality family bonding time in the kitchen,” laughs Schneider. Her mom will come over and help chop produce, and husband McClure holds the title of Resident Pickle Master. “Who needs date night when you can hang out over a steamy water bath canner together?”

Erin Schneider teaching a canning workshop at the Reedsburg Fermentation Fest: A Live Culture Convergence in Reedsburg, Wisconsin. COURTESY OF HILLTOP COMMUNITY FARM

Mixed Bag: Other Possible Cottage Food Products

Depending on your state, you may have an additional, mixed bag of products you can sell that may include dried mixes, herbal blends, chocolates, butters, condiments, dried pasta, roasted products — even cotton candy! There’s no rhyme or reason to the list. Some of the items could just be things some person in that state really wanted to make in their home kitchen to sell to the public. Don’t be surprised if your state allows one product while a neighboring state does not.

Rice Krispies “sandwiches” sold at the International Chocolate Festival at the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Coral Gables, Florida. JOHN D. IVANKO

Check your state laws to see if any of the following items are possible:

• Candy, such as brittle and toffee

• Chocolate-covered nonperishable foods, such as nuts and dried fruit

• Chocolate-covered pretzels, marshmallows, Rice Krispie treats and graham crackers

• Cotton candy

• Dried fruit

• Dried pasta

• Dry baking mixes

• Granola, cereals and trail mixes

• Herb blends and dried mole paste

• Honey and sweet sorghum syrup

• Nut mixes and nut butters

• Popcorn

• Vinegar and mustard

• Roasted coffee

• Dried tea and dried tea blends

• Waffle cones and pizelles

Handmade chocolates sold at the International Chocolate Festival at the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Coral Gables, Florida. JOHN D. IVANKO

Question 2: Where Can You Sell Your Products?

Each cottage food law will dictate where you can sell your product directly to the public. In Montana and Nebraska currently, two of the states with the most restrictive cottage food laws, you can only sell your approved products at a farmers’ market. That’s it.

Even if your state’s law allows sales at a farmers’ market, that doesn’t mean this venue must allow you to sell there. Some farmers’ markets have bylaws or rules that exclude cottage food enterprises. For example, the Dane County Farmers’ Market held in Madison, Wisconsin — one of the largest in the nation — requires that canned products be made in a licensed commercial kitchen.

Many states, however, offer a lot more flexibility in terms of the sales venues. The more options the better, in terms of reaching potential customers. The states with the greatest sales venue options often include direct delivery, home pickup and mail order.

Question 3: How Are You Allowed to Sell Your Products?

Regardless of the state, all cottage food laws permit direct sales to the public. Some of the more restrictive states, however, only allow sales that are direct-to-customer. Read: no indirect sales to other businesses that resell your product. But in more than a dozen states, products can be sold through indirect or wholesale channels, to restaurants, specialty food shops, the local food cooperative or even Whole Foods Market.

If, or when, the time comes to scale up and turn your micro-enterprise into a macro-business and offer your products through a wider assortment of channels than are permitted by your cottage food law, you may have to rent a licensed food production facility, or build a second on-site, commercial kitchen if allowed in your state. Expanding along a continuum, your business may either scale up modestly to serve a few small retailers or become an all-hands-on-deck, full-time endeavor with employees, production in a commercially licensed facility, huge financial demands and plenty of governmental red tape to keep you busy seven days a week. At that point, it’s no longer for a casual baker or pickle-maker.

Under no circumstances are you ever “catering.” Cottage food laws do not permit food service. You may deliver your products to a customer, but not display or serve them. You can produce certain foods in your home kitchen and have them consumed off premises — just don’t slice, plate or otherwise be involved in serving your product.

With rare exceptions, your cottage food-approved products must, in fact, be made in your home kitchen. If you decide to scale up to sell via indirect channels (covered in the final section of this book), you’ll be renting a commercial kitchen somewhere or building one in your home. If in doubt, check the section of your state’s law related to the “workplace.”

Question 4: How Much Can You Sell of Your Products?

Most states have a gross sales cap on the products you’re selling. This refers to the maximum gross sales your operations can reach per year, and range from $5,000 to $45,000. More than twelve states with cottage food laws allow unlimited sales with no gross sales caps.

What Products do You Want to Sell, and Which are Worth Selling?

Now that you have an idea of what you can legally sell in your state, what can you make that’s worth selling?

Here’s where the fun starts with testing out your food product ideas. If you already have a popular product, at least with the in-laws and co-workers, then jump to the next chapter and proceed. Otherwise you’ll need to sort out some details, including determining your products, checking your recipes and figuring out your market niche. As we’ll cover in the forthcoming marketing chapters, these considerations play an important role in the story about your product and business.

Product Selection

At this stage of your evaluation, what products did you have in mind? There are several approaches you might take to selecting your product.

• Ingredients: are the ingredients or products going to be organic, made with whole grain, kosher, allergen-free, without preservatives or artificial ingredients or gluten-free?

• Recipe focused: are the recipes unique or rare family recipes that are popular with family and friends? Is the recipe an all-from-scratch item or do you take shortcuts with pre-made crusts or fillings? Is your focus on ethnic cuisine, cultural food items or a seasonal specialty item?

• Sourcing of ingredients: will your products come from your neighbor’s fruit trees, your backyard, farmers’ market, the supermarket, Costco? How local are your local ingredients? Depending on your products, some of the ingredients may come from a combination of these sources.

Market Niche

When you break down your ingredient list, what most of us are selling is nothing more than the following:

• Pickles: cucumbers, plus vinegar, salt, sugar and spices

• Bread: flour, salt, yeast and water

• Preserves: fruit, sugar and water

• Cupcakes: sugar, butter, eggs, flour

In many cases, there may be similar products available where you live. What makes yours different — and better? In some cases, if your ingredients are from a neighbor’s fruit trees, a cherished ethnic recipe passed down several generations or a unique product you’ve developed and perfected yourself, these may be reason enough for a successful launch in your neighborhood. A market niche is a defined segment of a larger market you’ve identified as a potentially financially rewarding opportunity; more on this in Chapter 4, when we dig in and define your product from a marketing perspective.

Follow the Trends

Your business might be small, but you can still take advantage of emerging food trends, creating products that target what shoppers currently seek. Some market niches to explore might be the following:

• Gluten-free

Only 1 in 133 Americans are diagnosed with celiac disease, unable to tolerate gluten in their diet, according to the National Foundation for Celiac Awareness. But gluten-free appears to be the hot health trend with more than 30 percent of Americans claiming to avoid gluten, reveals the consumer research firm NPD Group. According to Mintel, another market research firm, the gluten-free product category will grow 48 percent from 2013 to 2015, reaching sales of $15.6 billion in 2016. Bakery items such as bread products, cookies and snacks hold the largest market share at nearly 24 percent.

• Allergy-free

According to the Mayo Clinic, eight foods account for 90 percent of all food allergies, five of which are common in baked goods: peanuts, tree nuts, milk, eggs and wheat (soy, fish and shellfish also made the list). More of us are being diagnosed as lactose-intolerant, so consumption of milk and other dairy products is out.

• Organic

Total organic sales in the United States continue to rise, up nearly 10 percent annually and growing from $1 billion in 1990 to more than $26 billion in 2010, according to the Organic Trade Association.

• Local

Research from Sullivan Higdon & Sink’s FoodThink, “A Fresh Look at Organic and Local” 2012, finds that “70 percent of consumers would like to know more about where food comes from.” They found that local was hot: “The vast majority of consumers (79 percent) would like to buy more local food, and almost 6 in 10 (59%) consumers say it’s important when buying food that it be locally sourced, grown or made.” Additionally, the National Restaurant Association’s 2014 Culinary Forecast included locally grown produce, hyper-local restaurant sourcing of fresh items and farm/estate branded products on their Top 10 Trends list.

• Ethnic flavors

Does your own family heritage offer unique specialty items folks can’t purchase elsewhere? Ethnic flavors continue to increase in popularity, particularly from Mexico and Latin American countries, according to the Flavor Forecast from McCormick & Co.

Getting the spices just right for your pumpkin cookies may involve plenty of trial and error, mixing and matching and lots of tasting. Besides taste and flavor, you’ll want consistency, since you’ll get a bad reputation quickly if the delicious muffins you made one week are too sweet or flavorless the following week. McDonald’s has built its quick-service restaurant empire around this idea of consistency — anywhere on planet Earth. It may not be the healthiest food in the world, but their Big Mac tastes exactly the same in Monroe, Wisconsin, as it does in Moscow, Russia. Customers expect this.

When you make your product with your recipe, does it turn out the same every time, day in and day out? Or does humidity, temperature or other factors create havoc with either your process or the ingredients?

Size is also an issue in consistency. Your cookies, bread or other baked items should be about the same size for the same price.

Carrot cake. JOHN D. IVANKO

Product Testing

After nailing your recipes, it’s time to test the product, since we’re talking about something perishable. Your criteria might include taste, flavor, texture, shelf life (fresh, day old, best eaten fresh, longer term), labor involved, waste, space needs, speed of preparation and consistency.

It’s important to have an honest and objective audience to help in your product testing. Are your pineapple salsa, pickled dilly beans or magical muffins as good as everyone says? Many people, as well-meaning as they may seem, will tell you what they think you want to hear. As you develop your products or product lines, it’s important to find honest and objective testers who can provide practical feedback. Don’t forget to “hire” your son or granddaughter as marketing consultants; kids can offer incredibly honest and fresh perspectives on your products and how they taste.

Product testing at this phase is different than completing a market feasibility study, where you examine a host of other variables, many having to do as much with marketing considerations and customer needs as taste. More on this in Chapter 9, after you’ve pulled together your ideas on marketing.

Authors’ son Liam… savoring a sweet treat. Kids can be great taste-testers. JOHN D. IVANKO