If the Restoration musician Daniel Henstridge (ca. 1650–1736) is remembered for anything today, it is for the collection of sacred-music manuscripts he acquired during his long career as a cathedral organist at Gloucester (from 1666), Rochester (from 1674), and Canterbury (from 1698).1 Recent research has shown that Henstridge was an unusually significant copyist of liturgical repertory not so much because of the quantity of music he produced but for its content (see the first section of table 11.1). Robert Shay and Robert Thompson have demonstrated, for example, that Henstridge copied a number of unique works by Purcell, as well as early versions of pieces that do not always survive in the main London sources of the composer’s music.2 Indeed, the extensive Flackton collection shows Henstridge to have been an important collector of music, both in terms of his own copying and in his acquisition of works from other musicians, which again include rare and unique material.

While the significance of Henstridge’s manuscripts of sacred music has been acknowledged by several scholars, his copying of music in other genres has attracted little interest, a tendency that has obscured the richness and diversity of the musical interactions and collaborations he experienced during his career. As section 2 of table 11.1 shows, he may have taught members of two Kent families: the Filmers, employers of Frances Forcer and William Turner, whose hands appear alongside that of Henstridge in US-NH Filmer MS 17,3 and the Delaunes, who owned GB-Lbl MS Mus. 1625.4 Additionally, Henstridge was almost certainly responsible for educating the choristers at Canterbury, implied by his copy of passages on canon by Elway Bevin and Giovanni Coperario’s composition rules and solmization exercises, both later stored in GB-Lbl Add. MS 31403 among teaching materials associated with Canterbury.5

Table 11.1 Daniel Henstridge’s Autograph and Partial Autograph Manuscripts.

Shelfmark |

Description |

1. Liturgical Music |

|

GB-CA MSS 9–11 |

Canterbury organbooks |

GB-GL MSS 106–7, 109–12 |

Gloucester partbooks |

GB-CA MSS 1a and GB-Lbl MS K.7.e.2 |

Canterbury copies of Barnard, First Book of Selected Church Musick, with manuscript additions including some by Henstridge |

US-NH Filmer MS 21 |

Rochester countertenor partbook fragment |

GB-Lbl Add. MSS 30931–3 |

Large group of loose-leaf manuscripts, mainly sacred repertory, including many in the hand of Henstridge and others apparently collected by him |

US-LAuc MS fC6966/M4/A627/1700 |

Folio scorebook of sacred music, with some instrumental repertory at reverse end |

2. Keyboard music GB-Lbl Add. MS 31403 |

Folio manuscript of keyboard music and pedagogical materials linked to Canterbury, started by Elway Bevin, and continued by Henstridge and eighteenth-century hands |

GB-Lbl MS Mus. 1625 |

Small oblong volume of harpsichord music, mainly settings, copied by Henstridge c. 1705; rudimentary notation instructions on opening pages |

US-NH Filmer MS 17 |

Miscellaneous oblong manuscript including vocal and keyboard music in several hands, including those of Frances Forcer and William Turner as well as Henstridge, who copied a keyboard piece and incomplete songs |

3. St. Cecilia’s Day odes GB-Lbl Add. MS 33240, fols 1–6 |

Henry Purcell, Welcome to All the Pleasures, organ part |

GB-Ob T MS 1309 |

Henry Purcell, Hail! Bright Cecilia, performing parts |

4. Secular songs and catches |

|

GB-Cfm Mu MS 118 |

Folio manuscript of secular songs and catches, mainly copied by Henstridge; one other copyist |

GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397 |

Oblong duodecimo manuscript containing secular songs and catches in Henstridge’s hand; one piece in another hand |

The third group of sources in the table, comprising performing parts for Henry Purcell’s two best-known St. Cecilia’s Day odes, suggests another type of music making altogether: Ford has argued convincingly that they demonstrate Henstridge’s involvement in the creation of a musical society at Canterbury that predated the group that certainly did exist there from the 1720s.6 This organization probably included a broad mix of professional musicians and members of the civic community, like the equivalent “Musical Society” in London described by Bryan White in his contribution to this volume.7 However, it is the final pair of manuscripts, containing a large quantity of simple songs, catches, and drinking songs, that has received the least attention in the scholarly literature. They confirm Henstridge’s participation in informal music making in the home and tavern, where amateur music lovers and professional musicians alike regularly gathered together to sing and play at their leisure.

Taken together, the surviving manuscripts to which Henstridge contributed provide a representative cross-section of his regular musical activities. They depict vividly the fluid boundaries within which musicians operated in the early modern period, providing material evidence not only of his activities as a cathedral musician and as an employee of private aristocratic patrons like the Filmers and Delaunes, but also showing him to have worked alongside people of the merchant classes who were involved with St. Cecilia’s Day celebrations, and in all probability to have mixed with people from across all these backgrounds in the social music making implied by the contents of GB-Cfm Mu MS 118 and GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397. The neglect of these two song manuscripts in particular provides a useful parallel to the keyboard manuscripts explored by Candace Bailey in this volume, because the type of repertory they contain has consistently been dismissed for precisely the same reasons—that much of it appears to be musically undemanding and that it is associated with low-level so-called “amateur” and “domestic” performance8—modern categorizations which, as we shall see, are as inappropriate here as they are for Bailey’s keyboard collections, and equally likely to set up false boundaries leading to misinterpretation of their contents.

Indeed, just as Bailey suggests that the notation of the keyboard manuscripts can be deceptively simple—hiding the fact that it was designed to allow an experienced player brought up in the art of improvisation the freedom to add to and adapt what was written down9—Henstridge’s song manuscripts also mask a wealth of information on the often-intricate and highly creative performing practices of this apparently “simple” repertory, even as it was performed in the most informal of contexts.

The limited scholarly interest in GB-Cfm Mu MS 118 and GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397 seems at first entirely understandable because both manuscripts seem to have been copied from readily available contemporary printed music.10

Closer inspection of both volumes, however, demonstrates not only that Henstridge’s main sources were not printed volumes but also that his song transcriptions include unusual and unique versions of some pieces that have hitherto gone unnoticed. Indeed, Henstridge’s copying preserves strong traces of the performing traditions for which the songs were created and therefore has significant implications for our understanding of the way in which this repertory was performed in the taverns and other informal settings where it thrived. In this respect, a further parallel presents itself, this time with aural transmission cultures reflected in the early modern pedagogical lute manuscripts explored in Graham Freeman’s essay in this volume. Here, too, we find transcriptions by Henstridge that blur the boundaries between music as heard and music as notated, and that challenge our assumptions about the functions and interpretation of musical notation in this period. These footprints of aural transmission are strongest in GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397, and it is on this fascinating manuscript, and the tantalizing glimpses it provides of a little-understood side of everyday musical life in seventeenth-century England, that this essay concentrates.

Even before considering its contents, GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397 is a striking source: in an unusual oblong duodecimo format, it measures just 62 mm x 156 mm. Each of the book’s ninety-six main leaves is ruled with four five-line staves, which are thus only slightly smaller than those in standard quarto or even folio manuscripts. Henstridge’s writing is nevertheless frequently tiny, aided by his use of a very thin nib for some entries. Many pieces contain alterations or corrections, and the copying is often untidy, giving the impression that it was completed quickly; figure 11.1, showing Robert Smith’s “How Bonny and Brisk,” is typical. Frequent changes of ink color and hand size additionally suggest that this was a book into which Henstridge added music gradually. This is also implied by the lack of organization of its contents, which comprise seventy pieces, including solo songs and dialogues—usually only their melody lines—as well as catches and drinking songs. Taken together, the physical characteristics of the manuscript point toward it having been Henstridge’s personal musical notebook. It would appear from its repertory that the manuscript was used by Henstridge throughout most of the 1680s.11

Figure 11.1 Robert Smith, “How Bonny and Brisk;” GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397, fols. 11v–12r, © The British Library Board.

There are no annotations in the book to identify either its function or its relationship to other manuscripts used by Henstridge, but remarks included in a songbook by Edward Lowe (ca. 1610–82) may well provide some clues: GB-Lbl Add. MS 29396 is a large folio manuscript containing precisely the same sort of repertory as Henstridge’s book but copied over four decades from the 1640s.12 Like GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397, Lowe’s manuscript contains copies of music that differ from those in contemporary print publications, and his copying includes a number of other similarities to Henstridge’s, as we shall see.13 Significantly, Lowe twice included an annotation at the end of songs for which he had copied only the first verse of text, to indicate that “The rest of ye words are in my pocket Manuscript.”14 The implication is that Lowe had a small notebook like Henstridge’s, in which he jotted down music that he later transcribed into this scorebook.

Lowe’s “pocket Manuscript” no longer survives, so we cannot tell if it was similar to GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397, but Henstridge’s notebook seems to have been designed precisely to fit into a deep pocket—indeed its duodecimo format is shared with other types of book that were often intended to be portable, such as psalters. For example, the 1673 edition of Sternhold and Hopkins’s Whole Book of Psalms measures 80 x 155 mm, and US-NH Filmer MS 32, a personal psalm manuscript entitled “Robert Filmer His Booke: of psalmes,” is a similar sort of duodecimo.15 Presumably, then, Henstridge carried this pocket book with him when he went to the tavern, or to music meetings, as a ready-made source of songs and catches. Whether he also transcribed them into a larger book equivalent to Lowe’s manuscript is more difficult to judge: his large songbook, GB-Cfm Mu MS 118, would seem the obvious candidate, but it was not personal to Henstridge—another hand is present throughout—and the ten pieces it shares with the pocket book have a complex textual relationship to GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397. If there was a companion folio volume, it appears to have been lost.

For our purposes, the more interesting question is where and how Henstridge acquired the pieces in his pocket book. Some of his exemplars do seem to have been printed sources. About eight of the songs, and many of the catches, are sufficiently similar to the versions given in contemporary print publications to make this feasible, and one of these—his copy of Purcell’s Mad Bess of Bedlam, “From Silent Shades”—certainly shows signs of a direct link with Playford’s printed copy of the song published in the fourth book of Choice Ayres, Songs and Dialogues in 1683.16 As Laurie notes, a misprint in Playford’s edition at “Did’st thou not see my love as he pass’d by you?” (from m. 57) results in rhythmic values that do not add up.17 The problem measure is adjusted in different ways in a number of contemporary manuscripts, including in Henstridge’s pocket book, where his apparent deletion and correction of the area around the rests suggests some indecision about which possible solution to adopt.18

Elsewhere, it is sometimes implied strongly that Henstridge had access to versions of songs that were circulating in manuscript, independent of printed copies of the same repertory. This is likely where significant differences between his copies and the printed sources are concordant with readings in other manuscripts. For instance, Henstridge’s copy of Blow’s song “Alexis, Dear Alexis” matches exactly the version of the piece in the Oxford source GB-Lbl Add. MS 33235, but these manuscripts’ readings differ from the song as it was printed in the 1684 edition of Choice Ayres, both in the patterns of repetition given for each section, and more especially in the continuo accompaniment part.19 Another example is John Abell’s ostinato song “High State and Honours,” which is unusual for having a ground bass of varying lengths, sometimes five bars, sometimes six, depending on whether the closing note of the ostinato is elided with the first note of the next statement. These changing patterns of repetition differ between Henstridge’s copy in GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397 and the song as it was printed in the 1683 Choice Ayres, with corresponding variants in the vocal line.20 However, the structure of Henstridge’s version is followed precisely in GB-Lbl Add. MS 19759, a songbook owned by Charles Campelman and dated 1681.

Thus far, Henstridge’s copying in GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397 does not appear exceptional: the above examples suggest that he was collecting music through notated sources, including both print publications and manuscripts. Henstridge’s versions are rarely exactly the same as other surviving notated copies, but this is not out of the ordinary: it was normal for English scribes in this period to incorporate small changes into the music they copied—features for which Alan Howard coined the useful term background variation, which include minor differences of rhythm, ornamentation, the register of notes in the continuo part, and so on.21 The patterns of variants across sources of songs in particular indicate a general flexibility in the textual transmission of the repertory. But in some of the pieces in GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397, the differences between what Henstridge notated and what can be found in other surviving sources are considerably more extreme than those seen in other situations, and they hint at an entirely different method of dissemination.

One example that is particularly illuminating in this regard is Pietro Reggio’s “Arise Ye Subterranean Winds” (The Tempest, 1674 production), which Henstridge entered on fols. 78v–77v at the reverse end of his pocket book. This transcription stands out because of the unusual nature of the text Henstridge entered below the stave (see figure 11.2).22 Although Henstridge’s thick nib and evidently hasty writing makes the text difficult to read, it can clearly be seen that he copied the text twice. His initial copying includes not only unorthodox spelling, even for the seventeenth century—such as “Aureise” for “Arise” in the opening phrase—but also many words to which an additional syllable “a” appears to have been appended. Thus he originally copied the phrase “more to distract their guilty minds” as “more-a to-a de-a-stract dear-a gilty moing.” The presence of these extra syllables, together with the spelling used for particular words—“moing” for “mind,” “vicha” for “which,” “owl” for “howl”—imply strongly that Henstridge’s first version of the text was a pseudo-phonetic transcription of a performance he had heard of a piece with which he was not already familiar, and that the singer was not a native English speaker. Indeed, the apparent mispronunciation he recorded makes it likely that the singer was Italian; it could even have been Reggio himself, despite the use of the treble clef for the melodic line.23 Henstridge apparently entered the second set of words in order to provide a correct copy, but it is not clear from where he acquired this text: there is one variant line that I have been unable to find in any other surviving sources, including the printed playbook.24 What is more significant is the fact that the music Henstridge copied fits with the pseudo-phonetic words, not the “corrected” text: each of the extra syllables has a note underlaid. Consequently, this version of the melodic line differs substantially from the song as Reggio himself published it in his Songs of 1680, in addition to which Henstridge’s copy includes extensive notated ornamentation not found in other sources. It is therefore difficult to interpret his version of the piece as anything other than a literal transcription of a specific performance Henstridge had recently (just?) heard and wanted to preserve in his personal musical notebook, made without reference to a notated exemplar. It therefore reveals a good deal about the creative role of the performer.

Figure 11.2 Pietro Reggio, “Arise, Ye Subterranean Winds,” Opening; GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397, fol. 78V (inv.), © The British Library Board.

Henstridge’s copy suggests that the performer’s interpretation resulted in radical transformation of the music in relation to the composer’s authorized publication. Musical example 11.1 shows the opening three phrases of the song as notated in GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397 and in Reggio’s 1680 book of songs, which was almost certainly already published by the time Henstridge copied his version.25 Apart from the large number of repeated notes included in the pocketbook version to accommodate the extra syllables, the manuscript suggests that phrases were elongated and contracted relative to the published song: two beats are added after the initial rising arpeggio on “arise,” but in the second phrase, “more to distract” enters a beat early. Substantial ornamentation results in an extra half measure on “subterranean” and one further quarter note added for a pictorial slide up to “rise” at the end of the extract. There is no accompaniment part to indicate how the continuo might have fitted against this elaboration, but it is implied in both cases that the penultimate note before each cadence resolution would have been sustained.26 Obviously, some allowance has to be made here for the possibility that Henstridge might have transcribed either inaccurately or approximately, and he does seem to have had some difficulty fitting the music he remembered into conventional measures, because his short second measure has two-and-a-half beats. Nevertheless, the impression given is that the singer incorporated considerably more elaborate melodic ornamentation into the music than is suggested in Reggio’s own singing treatise, The Art of Singing, published in 1677—which included an example from “Arise Ye Subterranean Winds” for which Reggio only recommended the addition of a simple trillo27—or than would be common in a modern historically informed performance based on the printed score. Even if it was the particular context in which this copy was made that caused the singer to give an exceptionally elaborate interpretation (or even led Henstridge to exaggerate in his copying), the performance-practice implications of this copy are startling.

Musical Example 11.1 Opening of Reggio’s “Arise Ye Subterranean Winds;” (a) as copied by Daniel Henstridge in GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397, fol. 78v (inv); (b) as printed in Songs Set by Signior Pietro Reggio (London, 1680), 12.

Although it may be difficult for us to conceive of this kind of aural transcription as a practical possibility, given the speed of working and short-term memory feats that would be required, such transmission routes were well developed in many walks of life in seventeenth-century England: Freeman’s chapter in this volume highlights the evidence that sermons and poetry were often written down from memory, for example.28 We also know from Pepys’s diary that audience members sometimes tried to write down excerpts of material they heard in the theater. During a performance of The Tempest in 1668, Pepys attempted to transcribe the “Echo” song, “Go Thy Way,” from act 3, scene 4, but had to seek the help of the actor who had performed it to complete his copy.29

Because Pepys had pressed John Banister to write out the music of the song for him some days earlier, we can be sure that he himself concentrated only on the text in this instance.30 However, Freeman’s assessment of the transmission of lute music from this period suggests that much of that repertory was accumulated initially through aural transmission, particularly in pedagogical contexts.31 Moreover, Mary Chan’s research on surviving manuscripts associated with music meetings held during the Commonwealth period has provided clear evidence that similar aural transmission routes were also used for precisely the genres of music preserved in Henstridge’s pocket manuscript: in a note written next to a transcription in John Hilton’s song manuscript GB-Lbl Add. MS 11608, the anonymous scribe remarks, “The treble I tooke & prickt downe as mr Thorpe sung it.”32 Chan also detected signs of memorized transcription in a related manuscript, GB-Lbl Egerton MS 2013, including the use of shorthand notation of texts and partial transcription of the continuo part.33 Notably, incomplete or missing accompaniment parts are also a characteristic of Edward Lowe’s folio manuscript, GB-Lbl Add. MS 29396, which, taken together with his comments about his “pocket Manuscript” cited above, may suggest that he too entered some of the material in this book via aural transcription.

Henstridge’s eccentric version of Reggio’s “Arise Ye Subterranean Winds” provides the clue we need to identify GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397 as a Restoration equivalent to the manuscripts Chan has found for the Commonwealth period: not only does it include repertory that was entered using “standard” textual transmission routes, but there is also material in the book that Henstridge almost certainly acquired aurally during his musical encounters with colleagues, acquaintances, and fellow professionals. While none of the other pieces sticks out quite as readily as the Reggio song, a number of the pieces Henstridge transcribed contain one or more of four main features that appear to be indicative of memorized transcription:

1. There is evidence that the scribe was relying on what he heard, and could not always fully understand the text being sung.

2. The notation shows an unusual flexibility in the interpretation of rhythm and phrase structure, mainly in declamatory songs.

3. Ornamentation is more densely notated than in printed sources, and is often included in the staff notation rather than through use of ornament signs.

4. The transmission of the melody line is privileged above that of the accompaniment, which is only partly entered, or omitted altogether.

The first of these features is clearly demonstrated by one of the four Italian songs in the book: like the Reggio song, its text must be a pseudo-phonetic transcription of the Italian (see figure 11.3). Clearly, Henstridge was no Italian scholar.34 Beginning “Amanti fuggite” (“Amonte fougete” according to Henstridge), the song’s final line should read “Quel frutto che cade, più dolce non e” (The fruit that falls is no longer sweet), but is transcribed by Henstridge as “kel fruto ke kaudi[,] Pudoulchi no na.”35 The musical setting has what I believe to be its earliest concordance in GB-Cmc MS 2591, one of the manuscripts copied for Pepys by Cesare Morelli, whom he employed as his guitar teacher probably between ca. 1679 and 1682.36 In the “Catalogue” of the contents given on fols. 164v–165r of MS 2591, Morelli clearly identifies himself as the composer of this song, which poses interesting questions about how Henstridge may have become aware of its existence, particularly because he apparently did so in the context of its being performed.37 What is interesting from our perspective is that, in contrast to the text there are no clues in Henstridge’s notation that the music was transcribed from something other than a written source. It is clear to see why this copy should contrast so strongly with “Arise Ye Subterranean Winds”: stylistically, the song is very simple and therefore the kinds of interpretative freedoms that the declamatory style of Reggio’s song invited would simply not have been relevant in performance.38 But this alerts us to the possibility that equally straightforward English dance songs in the manuscript, whose texts Henstridge could have understood without difficulty and whose notation is equally “normal” looking, might also have been transcribed without the use of a notated exemplar.

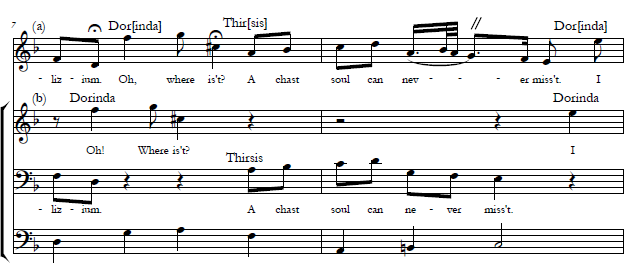

The second characteristic suggesting memorized transcription—flexibility in the interpretation of rhythm and phrase structure—is well demonstrated by Henstridge’s copy of Matthew Locke’s dialogue between Thirsis and Dorinda, “When Death Shall Part Us from These Kids.”39 Although the words here do not differ from the printed version of the song, the dialogue opens in declamatory style, and there are hints of the same kinds of flexibility in interpretation as we see in his copy of “Arise Ye Subterranean Winds.”40

Figure 11.3 “Amanti Fuggite”; GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397, fol. 56V (inv.), © The British Library Board.

As musical example 11.2 shows, the opening phrase is twice contracted in relation to the printed version of the song, while the coronas in the second and third systems imply possible expansion of the held notes at the ends of phrases; indeed, there is clear elongation of phrase openings later in the piece.41 We also have evidence here of the third characteristic of memorized transcription, because quite substantial ornamentation is added in relation to the printed sources, seen both through the use of signs and in the notation, and mainly occurring at cadences, although the elaboration is not on the same level as for Reggio’s song. The addition of the c-sharp in the phrase “is our cell Elizium?” also varies the placement and addition of accidentals in relation to the printed copy, something that features in several other parts of the piece and the manuscript as a whole, and which may suggest that incorporation of these sorts of pitch variants was considered at the time as a form of ornamentation that could be employed by performers or copyists.

As with most of the songs in the manuscript, Henstridge transcribed Locke’s dialogue with only its vocal lines, omitting the continuo accompaniment part—the fourth characteristic of aural transcription identified in the list. Of all the features of this method of notation we have encountered so far, this perhaps has the most significant implications for contemporary performance practices, something that is demonstrated more clearly where Henstridge did provide some or all of a bass line apparently without using an exemplar. The “problem” of the bass seems to have been solved by Henstridge partly through his choice of pieces: an unusually high proportion of the songs in the manuscript are written over a ground bass, which Henstridge usually wrote down on a facing page or at the end of his transcription, and which would have given a transcribed melody a ready-made accompaniment. But there are indications that for non-ostinato pieces the absence of a transcribed bass part was remedied in another way: several of the songs for which bass parts are provided or partially provided show significant variants in relation to other extant sources, or are completely unrelated to them, suggesting that Henstridge created his own new bass parts, or filled in gaps where his aural transcription was incomplete.

One likely example of this is the anonymous song “Could Man His Wish Obtain,” which has a bass part that imitates sections of the vocal melody, but for which only some sections of the bass were entered by Henstridge in GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397 (see figure 11.4).42 The copy gives the impression that he was attempting to transcribe both parts aurally but lost his way in the bass during the second section of the piece. In general, the relationship between this transcription and the printed version of the song in Choice Ayres, Songs and Dialogues (1683) is relatively close, but there are signs of aural transcription in the top vocal part’s ornamented melodic line and some small variants in the words.43 The relationship between the bass part and the treble is sufficiently simple that it would surely have been possible to remember much of the song with ease. However, at the point where the bass stops and reenters in the second section, Henstridge’s notation does not correspond with the printed score, and the final cadence seems simply to have been added as a typical cadential formula, providing a stereotyped ending to the piece. Additionally, the bass part at the end of the first section is entirely different (see musical example 11.3), and shows a different imitative relationship with the top part: perhaps Henstridge could remember enough to know that there was imitation but not in which measure it occurred.

Musical Example 11.2 Opening of Locke’s “When Death Shall Part Us from These Kids;” (a) as copied by Daniel Henstridge in GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397, fol. 18v; (b) as printed in Choice Ayres, Songs and Dialogues . . . The Second Edition (London, 1675), 80.

Figure 11.4 “Could Man His Wish Obtain;” GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397, fols. 12v–13r, © The British Library Board.

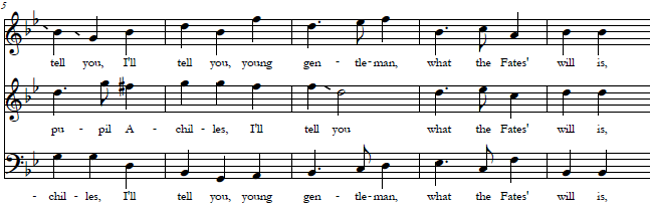

While this bass part seems to have originated as an aural transcription, some of the others in GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397 may well have been added independently after Henstridge completed an aural transcription of the melody line. This is perhaps most likely where the bass part is not laid out in score under the vocal line, but rather was copied as a separate part, and where the bass line itself seems not to be related to those given in other extant sources. A good example of this is “Why Is Your Faithful Slave Disdained,” for which Henstridge copied the vocal line on fol. 41v of the manuscript, and then the bass on fol. 42r, a part that differs substantially from the bass as it appears in two printed sources of 1688.44 As musical example 11.4 shows, both versions of the bass in the second half of the song include imitation again, but Henstridge’s copy has the bass entering at a different point—arguably less successfully—and he also elides the end of the part into the repeat. Apart from at the formulaic cadences in mm. 10-11, there is little in common between the two bass lines.

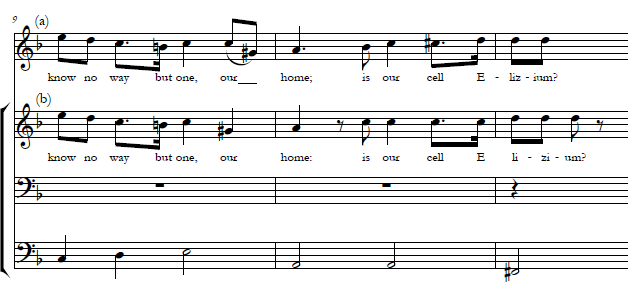

Musical Example 11.3 “Could Man His Wish Obtain,” mm. 8-14; (a) as copied by Daniel Henstridge in GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397, fol. 12v; (b) as printed in J. Playford, Choice Ayres, Songs and Dialogues . . . The Fourth Book, 5.

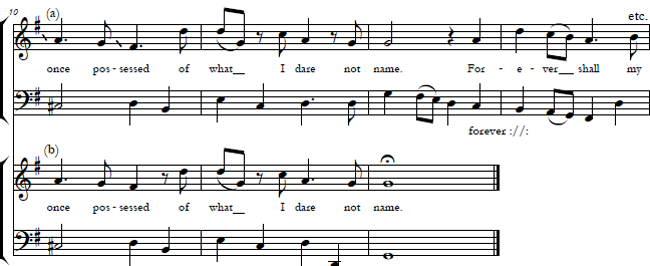

It is entirely possible that more than one version of this piece was in circulation in Henstridge’s lifetime, and that what we see here are revisions that Courteville himself carried out. However, the likelihood that Henstridge composed this bass line to go with the melody line of a song he transcribed aurally is heightened by evidence elsewhere in the manuscript that he did sometimes add in new parts of his own making. This is almost certainly the case for Michael Wise’s “Old Chiron Thus,” printed as a two-part song for treble and bass in Catch that Catch Can (1685) and in The Second Part of the Pleasant Musical Companion (1686), and also circulated widely in manuscript.45 Henstridge initially copied the treble and bass parts in score on fols. 61v–58r at the reverse end of the manuscript, in a version without significant variants from the printed copies, but at its conclusion he notated an additional treble part, lying mainly under the first one, which he signed at the end “D: Hens:,” as Shay and Thompson have noted.46 Henstridge did succeed in incorporating limited additional imitation into the added part (see musical example 11.5), but he was unable to fit in all the text, and the harmony in m. 5 is uncomfortable. In general, the added part uses a fair amount of parallel motion, especially with the upper part, but it is by no means dependent on it.

Musical Example 11.4 “Why Is the Faithful Slave Disdained?” mm. 6-12; (a) as copied by Daniel Henstridge in GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397, fol. 41v–42r; (b) as printed in The Banquet of Musick . . . The Second Book, 5.

These examples suggest that Henstridge’s copying in his pocket book was not just a matter of recording what he heard and transcribing pieces he was able to access in printed and manuscript sources: in some cases he also engaged creatively with the music he encountered, perhaps partly out of necessity, when he was transcribing aurally and was unable to take down all the parts he heard, and sometimes as a method of adapting and developing the material that was available to him. Taken as a whole, Henstridge’s copying in GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397 implies a number of significant adaptations to our understanding of the ways in which Restoration vocal music was performed in the period in relation to the versions of the music that were transmitted through print publication. First, it suggests that declamatory song may have incorporated greater flexibility of tempo than we might imagine today, particularly at the beginnings and ends of phrases, which seem to have been treated very freely. Second, ornamentation appears to have been applied much more extensively than is suggested by notated sources produced via more standard scribal transmission, particularly in declamatory styles, where such decoration was apparently allowed to disrupt meter, at least in the most dramatic music. Although the extreme ornamentation in Henstridge’s copies of Purcell’s Bess of Bedlam and “O Solitude” has been noted elsewhere as two isolated cases, in fact virtually every piece Henstridge transcribed is steeped in both ornamentation symbols—particularly the slide—and in decoration incorporated into the staff notation itself.47 Third, in privileging melody lines over accompaniments when transcribing aurally, Henstridge almost certainly created his own accompaniment parts, so that some pieces were probably performed with entirely different or partially variant bass lines from those transmitted in the notated sources. For a professional organist like Henstridge, it would probably have been easy to improvise an accompaniment for most of these songs, and some other Restoration sources—including Lowe’s songbook, as noted above, and Purcell’s autograph manuscript GB-Lg MS Safe 3—have examples of incomplete bass parts that imply similar practices.48 Finally, Henstridge’s creative engagement with the music he copied into the manuscript is also shown by his addition of at least one extra part, which is again a trait that can be seen in other manuscripts associated with aural transcription, such as Lowe’s songbook and the lute manuscripts discussed by Freeman elsewhere in this volume.49

Musical Example 11.5 Opening of “Old Chiron Thus Preach’d to His Pupil Achilles,” as copied by Daniel Henstridge with added middle part; GB-Lbl Add. 29397, fol. 61v (inv.) and 58r (inv.).

Daniel Henstridge’s tiny pocket manuscript thus holds a wealth of musical treasures concerning the performance of secular song in the Restoration period. The fact that it contains a good deal of material that also happens to have been printed by the Playfords in the 1680s is evidently indicative less of the sources Henstridge used when entering material into the manuscript than of the way in which the Playford prints reflect the popular repertory that was being sung in taverns and other places where musicians met together during the 1680s. Unlike these printed books, however, GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397 preserves something of the living tradition in which the music was performed, just like the group of sources that Chan was able to link to earlier music meetings in the Commonwealth period. Henstridge’s manuscript therefore has the potential to assist us in bridging the ever-difficult gap between notation and practice in Restoration England, as well as helping to create a more rounded picture of the way in which the music making of cathedral musicians like Henstridge involved them in a much wider range of social interactions than their occupational activities alone would suggest.

1. For details of Henstridge’s biography, see Ford, “Henstridge, Daniel,” GMO (accessed June 30, 2012). Ford notes that Henstridge effectively retired in 1718.

2. Shay and Thompson, Purcell Manuscripts, 221–226. On Henstridge’s London connections, see Ford, “Purcell as His Own Editor,” 48–49.

3. See Ford, “The Filmer Manuscripts,” 820–821, and Bailey, “The Challenge of Domesticity,” this volume, 119.

4. As suggested in Johnstone, “A New Source,” 67–69 and 77.

5. These begin on fol. 141 of GB-Lbl Add. MS 30933. For more on Lbl Add. MS 31403 and its possible functions, see Bailey, this volume, 118–119.

6. See Ford, “Henstridge, Daniel,” and Ford, “Minor Canons at Canterbury Cathedral,” 445–447.

7. See White, “Music and Merchants,” this volume, 156–7 and 159–60. Some members of the London Musical Society are listed in the prefatory material to Purcell’s A Musical Entertainment (1683) and Blow’s A Second Musical Entertainment (1684), but White has uncovered information about many more of the individuals who were involved with this “Musical Society.”

8. See Bailey, “The Challenge of Domesticity,” this volume, 114. Jack Westrup’s dismissal of Purcell’s extensive output of catches in a single sentence is typical (Purcell, 169–170): “Nothing need be said here of Purcell’s numerous catches . . . they are too slight to have any permanent significance.”

9. Bailey, “The Challenge of Domesticity,” this volume, 121–122.

10. Shay and Thompson, Purcell Manuscripts, 276. The three books are Lawes, Select Ayres of 1669 and two books published by John Playford: Choice Ayres . . . The Second Edition from 1675 and Choice Ayres . . . The Second Book, from 1679.

11. As suggested in Shay and Thompson, Purcell Manuscripts, 275–276.

12. As argued in Chan, “Edward Lowe’s Manuscript,” 440–454.

13. Ibid., 449.

14. One example occurs on fol. 75r, at the end of the song “How Happy’s That Pris’ner Who Conquers His Fate,” and another at the end of the following song, “Stay, Shut the Gate,” fol. 76r.

15. Ford, “The Filmer Manuscripts,” 823.

16. J. Playford, Choice Ayres . . . The Fourth Book, 45.

17. See Purcell, Secular Songs for Solo Voice, 28 and 281.

18. This passage is also corrected in GB-Cfm Mu MS 118, but the copy is in the unknown scribe’s hand, not Henstridge’s, and the solution differs from that given in GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397. The textual relationship between the pocket book and Playford’s printed edition remains complex, because Henstridge’s copy also incorporates significant additional melodic ornamentation.

19. See GB-Lbl Add. MS 33235, fol. 50r, GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397, fol. 62v, and J. Playford, Choice Ayres . . . The Fifth Book, 60. The Oxford provenance of GB-Lbl Add. MS 33235 is noted in Shay and Thompson, Purcell Manuscripts, 271. The only variants between the manuscript readings comprise some absent ties in GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397 and one variant harmony note in the treble part.

20. J. Playford, Choice Ayres . . . The Fourth Book, 21.

21. See Howard, “Understanding Creativity,” 97, and also the longer discussion of the concept in Herissone, Musical Creativity, 245–258.

22. The following two paragraphs are extracted from Herissone, Musical Creativity, 377–381.

23. In this period, songs printed in the treble clef were considered suitable for men’s voices when transposed down an octave; see Herissone, Music Theory in Seventeenth-Century England, 110. Reggio sang bass at the court of Queen Christina in Stockholm and in the French royal choir, and John Evelyn wrote on September 23, 1680, that he “sung admirably to a Guitarr & had a perfect good tenor and base &c.”; quoted in G. Rose, “Pietro Reggio,” 212.

24. [Shadwell], The Tempest or the Enchanted Island, 30. The variant line is “engender earthquakes, make whole countries shake and stately cities into deserts turn,” which Henstridge copied as “engender earthquakes, make whole cities burn and fateful countries into deserts turn.”

25. The song appears in modern edition in Locke, Dramatic Music, 42–45, using only the printed source (see the editorial commentary in ibid., 235). In addition to Henstridge’s copy, it also survives in two other contemporary manuscripts, GB-Lbl Add. MS 19759 and in GB-Lbl Add. MS 33234. Both these copies contain variants of their own, with hints of aural transcription. Their characteristics are examined in Herissone, Musical Creativity, 381–383.

26. Had the singer been Reggio himself, he would surely have provided his own accompaniment: Pepys noted in July 1664 that Reggio sang “to the theorbo most neatly” (quoted in G. Rose and Spencer, “Reggio, Pietro,” GMO (accessed June 20, 2012)), and Evelyn referred to his self-accompaniment on the guitar (see note 23 above). I am grateful to Alan Howard for this observation.

27. Reggio, The Art of Singing, 9. As Stephen Rose has noted (“Performance Practices,” 132–133), Reggio emphasized subtle dynamic shading as the principal expressive technique for the singer, and there is only brief mention of this kind of passaggi-like ornamentation (in The Art of Singing, 15).

28. See Freeman, “The Transmission of Lute Music,” this volume, 45–7.

29. Pepys, Diary, vol. 9, 195; quoted in Smyth, “Profit and Delight,” 114. Smyth suggests that this kind of transcription was probably widespread in this period, and may account for variants between copies of literary texts.

30. In the entry for May 7, 1668, he wrote that he “did get him [Banister] to prick me down the notes of the Echo in ‘The Tempest,’ which pleases me mightily”; Pepys, Diary, vol. 9, 189.

31. Freeman, “The Transmission of Lute Music,” this volume, 47–50.

32. The annotation occurs on fol. 63v; as quoted in Chan, “A Mid-Seventeenth-Century Music Meeting,” 233.

33. Ibid., 237.

34. Of the other three, “Dite O cieli” (Carissimi) is straightforwardly copied from the 1688 published version in Henry Playford’s The Banquet of Musick . . . The Second Book, 22, but the origins of the other two, “Ecco l’Alba”’(also Carissimi) and “Bel tempo” (anonymous) are not yet clear. Neither appears to have been printed in England in the Restoration period.

35. I am grateful to Michael Talbot and other delegates at the Fifteenth Biennial Conference on Baroque Music, University of Southampton, July 2012, for their assistance in deciphering this text, and to an anonymous reader for assistance in its identification.

36. This is a large and extravagantly copied book with the title “Songs & other Compositions Light, Grave, & Sacred, for a Single Voice. Adjusted to the particular Compass of mine; With a Thorough-Base on ye Ghitarr by Cesare Morelli” (written in Morelli’s hand rather than that of Pepys, despite the reference to the first person). Although the date 1693 is given on the front of the leather binding, Morelli left Pepys’s service to return to Flanders in 1682 (see Short, “Morelli, Cesare,” GMO (accessed June 1, 2015)). This song is found among the “Compositions Light,” on pp. 21–22 (fol. 14). A transcription is given in Morelli, Eight Songs for Samuel Pepys, 17–26. Kyropoulos identifies the text as an extract from a cantata by the mid-seventeenth-century Roman poet and singer Margherita Costa, Oh Dio, voi che mi dite (see ibid., 5).

37. The song must have circulated outside the context of Morelli’s employment by Pepys, because a later reference to the same text occurs in the 1701 volume of Christoph Ballard’s Meilleurs airs italiens, although no composer is listed here. The melody as given by Morelli was later used as air no. 32 in John Gay’s banned ballad opera Polly, act 2, scene 4, where it occurs with the replacement text “Fine women are devils.” See Gay, Polly: An Opera, 31, and the music notation paginated separately at the end of that volume, 7; see also Gay, The Beggar’s Opera and Polly, 118 and 180.

38. Nevertheless, the variants between Henstridge’s version of the song and that notated by Morelli indicate that the singer included added and variant ornamentation, although this is on a scale similar to that given for Locke’s dialogue in example 11.2, rather than being of the more extreme sort that Henstridge notated for “Arise Ye Subterranean Winds.”

39. GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397, fols. 18v–21v.

40. The song first appeared in print in J. Playford, Choice Ayres . . . The Second Edition, 80–84. It was reprinted identically in J. Playford, Choice Ayres . . . Newly Re-printed, 90–93, in 1676, and also in H. Playford, The Theater of Music . . . The Fourth and Last Book, 78–81, in 1687, where the part of Thirsis was placed in the bass clef, and where there is one rhythmic difference and one apparent misprint in the bass, but the text is otherwise identical.

41. Dorinda’s phrase “But in Elizium” begins on an eighth note in the printed copy, but on a quarter note in GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397; Thirsis’s next phrase, “Oh, there is neither hope nor fear,” starts on a quarter note in the printed version but a half note in Henstridge’s copy.

42. GB-Lbl Add. 29397, fols. 12v-13r.

43. J. Playford, Choice Ayres . . . The Fourth Book, 5. The song was also copied by Henstridge in GB-Cfm Mu MS 118, 55, a fifth lower than the versions in GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397 and Choice Ayres. There is a close relationship between GB-Cfm Mu MS 118 and the print publication—thus meaning no direct link between GB-Lbl Add. MS 29397 and GB-Cfm Mu MS 118—apart from transposition and a few examples of background variation, as well as minor variants in the bass line that result from the fact that the bass as given in GB-Cfm Mu MS 118 is apparently not a vocal line, and therefore has some sustained notes that are shown separated in the print publication; the manuscript version also omits four notes of the bass part between mm. 10 and 11.

44. See H. Playford, The Banquet of Musick . . . The Second Book, 5, and H. Playford, Vinculum Societatis . . . The Second Book, 19. Henstridge attributes the song to “Mr Courteville,” but it is anonymous in both printed versions.

45. J. Playford, Catch that Catch Can, no. 52; J. Playford, The Second Part of the Pleasant Musical Companion . . . The Second Edition, part II, no. 6.

46. Shay and Thompson, Purcell Manuscripts, 275–276.

47. S. Rose, “Performance Practices,” 147 n161; Purcell, Thirty Songs in Two Volumes, vol. 1, 30–35.

48. On the evidence for memorized copying in Purcell’s “Gresham” autograph, see Herissone, Musical Creativity, 368.

49. Lowe added parts to several songs in GB-Lbl Add. MS 29396; his addition to “The Thirsty Earth” is analyzed in ibid., 327–331.