From its debut in August 1770, a music sheet was included every month in the London Lady’s Magazine; or Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex, yielding a total of some four hundred songs by 1805, when music ceased as a regular feature.1 The Lady’s Magazine stood at the forefront of education for women in Georgian England, and its music sheets reflected the periodical’s twin goals of instruction and entertainment. As the century progressed, more works by earlier English composers appeared in addition to fashionable airs, demonstrating that the Lady’s Magazine also served as a medium to cultivate the heritage of British song among magazine readers. The monthly periodical format provided a fluid conduit to convey musics from a range of urban venues (theater, pleasure gardens, concert stage, and men’s convivial music clubs) directly into the domicile, thereby creating permeable boundaries between public and private spaces, genres, and repertoire.

On the title page of each issue, the Lady’s Magazine listed a song among the so-called “Embellishments” in the table of contents. While “embellishments” might suggest fashion, the varied nature of the plates is evident from a title page, such as July 1779, that itemized “the following Copper-Plates, viz. 1. An accurate Whole Sheet Map of Africa. 2. A beautiful historical Picture of Omrah restored: and 3. A Song, set to Music by Mr. Hudson.”2

At its zenith, the Lady’s Magazine reached perhaps fifteen thousand subscribers, making it as widespread as the venerable Gentleman’s Magazine (1731–1907), at the same price of sixpence per issue, and spanning more than a half-century before merging with rival publications.3 Despite the extensive circulation of the Lady’s Magazine, Jenny Batchelor cites difficulty of access and unanswerable questions about readership, purchasers, authors, and anonymous editors, all of which have contributed to a lack of definitive scholarship for the periodical.4 The “polite literature” that filled the issues was echoed by music deemed appropriate for the home, such as chaste love songs, but the magazine also circulated favorite airs and duets from English operas, occasional music, and catches from music societies. The Lady’s Magazine printed excerpts from more than twenty of George Frideric Handel’s odes and oratorios, as well as songs by many English composers of merit: Thomas Morley (ca. 1557–1602), William Boyce (1711–1779), Henry Purcell (1659–1695), Maurice Greene (1696–1755), Charles King (1687–1748), Samuel Howard (1710–1782), and Elizabeth Turner (d. 1756). The range of repertoires in the Lady’s Magazine gives a glimpse of domestic study and music making that mixed music from public venues into private or semiprivate, nonprofessional performances along a “performative continuum” broader than just inferior amateur entertainment in the home.5

The phenomenon of “magazine music” in literary periodicals for the general reader began even before the eighteenth century.6 In 1692, Huguenot refugee Peter Anthony Motteux initiated his elegant Gentleman’s Journal, or, the Monthly Miscellany (1692–1694), which contained a regular music supplement.7 Motteux was familiar with publication of engraved chansons in the premiere French miscellany, Le Mercure Galant (1672–1825). He understood the potential for a monthly periodical to deliver London’s culture of music and theater into the private domicile, but few entrepreneurs followed his model until 1731, when Edward Cave began publication of the Gentleman’s Magazine.8 Cave’s literary miscellany enticed a sizable readership with news, serialized fiction, essays, gossip, and advice.9 Cave popularized the term magazine, meaning a storehouse, to describe such a miscellany, but “storehouse” fails to connote the dynamic aspect of magazines to channel experience, spectacle, and fashion from Georgian London into distant towns and rural homes. Printing technologies enabled miscellanies to include illustrations of the latest buildings, monuments, celebrity portraits, theatrical scenes, and music from the stage and pleasure gardens.

Song lyrics were already staples of the “Poetical Essays” in the Gentleman’s Magazine when the first song score appeared in October 1737.10 The London Magazine (1732–1785), Universal Magazine (1747–1815), and other competitors soon added strophic airs and dance tunes for flute or violin to their poetry sections. These poems and song scores frequently cited both performer and venue, confirming that London literary miscellanies regularly brought music into the domicile from the theaters and pleasure gardens. Ranelagh and Vauxhall Gardens mounted nightly concerts that alternated overtures, concertos, and songs to entertain listeners as well as to provide ambiance for crowds as they strolled or chatted. Although the songs were typically genteel, their double entendre could be quite suggestive, whether in pastoral lyrics of love between shepherds and nymphs, or between Scottish lads and lasses.

Following the style and content of the Gentleman’s Magazine, Irish writer Oliver Goldsmith edited the first-titled Lady’s Magazine. Or Polite Companion for the Fair Sex (1759–1763), issued by John Coote.11 Goldsmith’s Lady’s Magazine contained a monthly song but often duplicated those in the Royal Magazine (1759–1771) or James Oswald’s Musical Magazine (1760), all produced by Coote, who attested that he was the publisher of some magazines, and the “proprietor” of others.12 Coote finally achieved a successful blend of content, tone, and features in 1770 with a redesigned Lady’s Magazine; or, Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex that relied less on the look of earlier London miscellanies.13

Many journals of the era promised to unite amusement and information, but the Lady’s Magazine’s pledge of “Entertainment and Instruction for the Ladies of these Kingdoms” was no idle claim.14 The periodical encompassed lengthy travel accounts, historical essays, and biographies of famous lives to improve, as well as to entertain, the household. As in much eighteenth-century literature directed at Englishwomen, ubiquitous tutelage in conduct and morality was encoded in sentimental stories, serialized novels, and sermonizing essays. While the magazine cultivated the British woman’s education, each page also presented models to construct her opinions and conduct.

Magazine music sheets were no exception. The Georgian view of music as a “metaphor for social order” embraced women’s practice and study as means to regulate the potentially disorderly pleasures of music.15 Most Lady’s Magazine scores fall into Leslie Ritchie’s three categories of women’s songs: songs of love, including romantic love as well as Christian caritas; pastoral songs; and songs of British nationalism.16 Although the majority of music was limited to numbers considered appropriate for the drawing room—not too long, not too difficult, and not too racy—the magazine introduced music from some public venues into the domestic realm but not without modifications. References to fashionable pleasure gardens disappeared. Lyrics that were too suggestive of inappropriate sentiments or behavior were revised into inoffensive pastoral verses. The music published in the Lady’s Magazine nevertheless challenges the notions that the songs published in household periodicals were insignificant, if not “pretty terrible,” and belonged to a domestic performance tradition “almost invariably judged to be of inferior or at best mediocre quality.”17

For young women of the upper and aspiring middle classes in Britain, the ability to sing and skill at the piano were desirable accomplishments, as well as pursuits preferable to novel reading or cards.18 “Musick,” declared a 1722 conduct book, “refines the Taste, polishes the Mind; and is an Entertainment . . . that preserves [Ladies] from the Rust of Idleness, that most pernicious Enemy to Virtue.”19 The Lady’s Magazine nurtured the musical tastes of readers with assistance from an unnamed “Music Master,” who was demonstrably Robert Hudson (1732–1815), a versatile singer associated with St. Paul’s Cathedral for sixty years, from choirboy to vicar choral and master of the choristers.20

The summary of composers with music in the Lady’s Magazine (see appendix) reveals that more than 100 selections were by Handel, and almost 150 were songs by Hudson.21 Most composers were British-born musicians or longtime residents such as Handel and Domenico Corri (1746–1825). In 1776, the selections reflected a mix of historical and contemporary numbers, with excerpts from Handel’s Jephtha, Semele, Samson, and Judas Maccabaeus, four of Hudson’s secular airs, a canzonet for two voices by Thomas Morley, an anonymous “Venetian Ballad” in Italian, and a song each by Philip Hodgson of Newcastle, Mr. Hoare of Taunton, Somerset, and an anonymous “correspondent.” Over time, the magazine’s musical offerings swelled to a modest storehouse of English song for the home, a collation of music primarily in English, by British composers, that accorded with English taste in current use and former practice.22

Magazine music inserts found a place in private collections and personal volumes of music, and song titles from the magazines often overlap with sheet music imprints in domestic collections.23 Music selections in the Lady’s Magazine were usually limited to one or both sides of a single loose sheet that facilitated removal to the keyboard or music stand for study or performance. The songs were not intended exclusively for female performers; some excerpts from Handel’s oratorios were tenor or baritone arias in their original clefs.24 Song texts sometimes expressed a male viewpoint, but could have been performed by either sex. While the insert usually indicated “Lady’s Magazine,” the month and year were not added until 1785, making it difficult to assign earlier song sheets with certainty. Monthly tables of contents were often no more specific than “Favorite New Song.”25

Short communications “To our Correspondents” appeared on the reverse side of the title page in most magazine issues. In November 1772, the journal editor wrote, “The song signed Iris, is obliged to be postponed . . . we shall send it as soon as possible to our composer, to be set to music.” Two months later, the musical setting “Iris,” by “Mr. Hudson,” appeared in the year-end supplementary issue. Another communication in March 1777 referred to him as the “Music Master.” Hudson’s three-decade involvement indicates that he valued his role at the Lady’s Magazine. Music instruction constituted a major strand in Hudson’s life. He served as almoner at St. Paul’s, in charge of schooling eight to ten choirboys from 1773 until 1793. Music pedagogy for women was also a personal concern, since his wife and daughter were professional musicians.26

Hudson chose magazine songs with texts that were suitably “polite,” or changed the words to reduce sensual allusions and double meanings in pastoral ballads. Through careful selection and occasional revision, he skirted around concerns voiced by Rev. John Bennett:

Many songs are couched in such indelicate language, and convey such a train of luscious ideas, as are only calculated to foil the purity of a youthful mind. . . . Indeed, church music is, in itself, more delightful than any other. What can be superior to some passages of Judas Maccabaeus, or the Messiah?27

Hudson enacted Bennett’s suggestion through oratorio selections in the magazine that embodied Christian piety and scriptural stories. Hudson’s topical songs celebrated the seasons, holidays, and special occasions of royal commemoration or military victory.

While Lady’s Magazine songs often displayed a prescriptive slant, Hudson injected more works by earlier English composers as the century progressed, interweaving the pedagogical intention of using the periodical as a vehicle to cultivate the heritage of British song for the domestic audience. With its academies and interest in “Ancient Music,” England evinced a burgeoning historical consciousness that Hudson transmitted to magazine readers.28 The historical emphasis in the Lady’s Magazine emerged in 1775, when a canzonet by Morley and catches by Greene, King, and Travers appeared in music inserts. Numerous oratorio excerpts began in 1776, well before the first Handel commemoration of 1784, and indicate the continuing “domestication” of Handel’s music that Suzanne Aspden describes in this volume. Excerpts from Hawkins’s General History of the Science and Practice of Music and Burney’s General History of Music, both published in 1776, soon appeared in the magazine.29

Nowhere did Hudson discuss the monthly music published in the magazine, but his musical tastes and values for domestic song performance have been preserved through his methodical choices. In addition to excerpts from odes and oratorios from English concert life, Hudson made selections from outstanding song collections, such as Boyce’s Lyra Britannica (1747–1759), inserted in the magazine during 1782, or Greene’s 1739 Sonnets to texts from Edmund Spencer’s Amoretti, in 1794 and 1795. He balanced fashion with propriety in selecting popular songs composed by contemporaries such as William Shield (1748–1809).

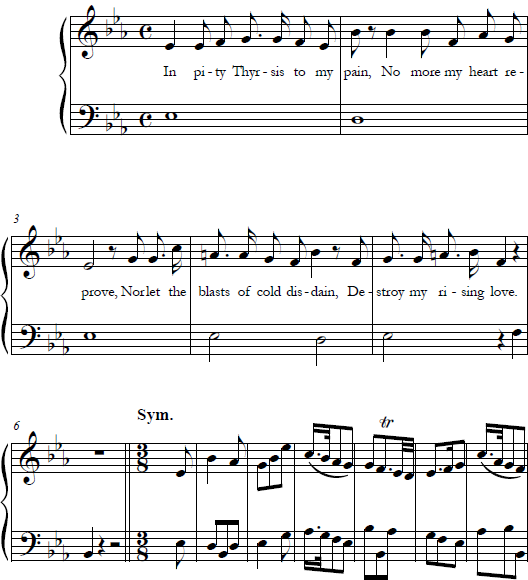

Four selections from the Lady’s Magazine—two composed by Hudson and two that he chose from other composers—illustrate a range of repertoire streams from varied venues that comingled in the periodical: pleasure garden air; patriotic music; part-song from men’s clubs; and “ancient music.” Hudson knew how to write a pleasant tune that fit the voice and sometimes placed it within a small scena that suggested the metropolitan venues of the stage or garden.30 Such a setting is “Thyrsis,” a pastoral scene of unsuccessful love published in December 1785, “at the Request of several Female Correspondents” (musical example 15.1).31 The song was already “ancient,” being a revision of “Love at First Sight,” the concluding song from The Myrtle, a collection of Hudson’s airs in the pleasure garden style of the 1750s.32 The figured bass indications were eliminated in the magazine, but the active bass line implies or completes the harmony when combined with the treble melody.33 The ardent recitative, “When I survey thy matchless Face, sure never raptur’d Lover cou’d in a Nymph such Beauties trace,” was reworded with supplication, “In pity Thyrsis to my pain, No more my heart reprove.” Five strophes beseeched a “heav’nly maid” for “A Med’cine to remove / The cruel pangs . . . from unsuccessful love.”34 The overt physicality of the original verses was replaced by the image of tentative love emerging like a flower in need of care. “Thyrsis” demonstrates how Hudson prepared a song from the public gardens for the genteel space of the drawing room by replacing visceral images with less vivid pastoral metaphors that nevertheless suggested sentiments of love.

Musical Example 15.1 Hudson, “Thyrsis,” Lady’s Magazine 16 (December 1785).

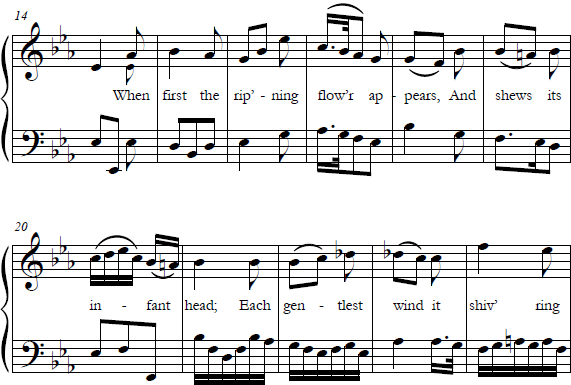

An ebullient example of Hudson’s song style for public celebration is the “Song on Nelson’s Glorious Victory,” a shower of praise following the Battle of the Nile in August 1798.35 This topical song provides a vibrant contrast to the polite amour of “Thyrsis.” The sturdy tune, with its rising scales, cheers of “Huzza,” and frequent unisons, seems to embody an English nation united during the glory days of the British Navy (musical example 15.2). Simple but memorable melodic phrases sung in unison, such as “Let three times three ascend the sky,” were a feature of Hudson’s patriotic numbers in the magazine. These national and occasional songs engaged British subjects far from the centers of political or military power, and contributed to a shared sense of Englishness. If not political enfranchisement, the song at least offered recognition that women, too, shared in the national dialogue and celebration of British identity.

Musical Example 15.2 Hudson, “Song on Nelson’s Glorious Victory,” Lady’s Magazine 29 (October 1798).

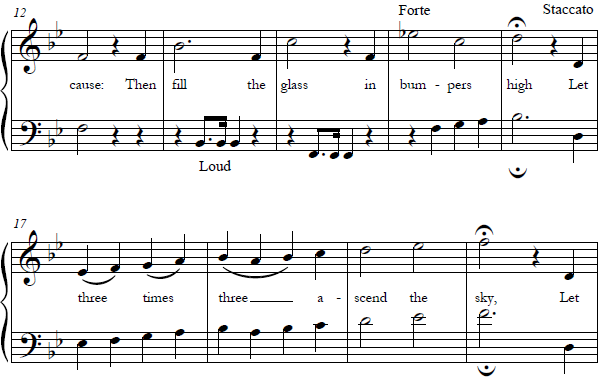

A departure from chaste music in the Lady’s Magazine came from the tradition of music clubs, in which gentlemen convened for dinner, wine, and a cappella glees and catches. Women could not be members, although some clubs presented an annual “Ladies Night.”36 Hudson may have wanted to extend the practice of part-songs and canzonets to women and men at home, but catches were notorious for their naughty lyrics. “On Music,” a catch by organist John Alcock Jr. (ca. 1740–1791), afforded a fresh, lively piece for domestic music making that stopped short of overstepping proprieties without altering John Oldham’s 1685 ode, “For an Anniversary of Musick Kept upon St. Cecilia’s Day” (musical example 15.3).37 The first voice sings the opening twelve-measure phrase, indicated “1” (“Music does all our joys refine . . .”), then proceeds to phrase “2” (“’Tis that gives rapture . . .”) as the next voice begins phrase “1,” and so on. The setting could be described as a round rather than a catch, because there are no “hocketing” rests within phrases that allow humorously inappropriate words from other parts to pop up unexpectedly during silences.38 The glees and catches in the magazine show that Hudson chose carefully to enlarge the range of acceptable domestic music with men’s semiprivate club repertoire.

Elizabeth Turner was the only significant woman composer identified by name in the magazine.39 Probably born during the 1720s, she was a soprano soloist in London concerts and oratorios from 1744 until her death in July 1756.40 Hudson and Turner certainly knew each other by professional reputation; indeed, Turner subscribed to one of Hudson’s Myrtle collections. They were performers well known in London venues, and they may have sung together in oratorios in the early 1750s. Turner self-published two books of songs in 1750 and 1756 with impressive lists of subscribers.41 Although they were not entered for copyright protection at Stationers’ Hall, her collections were never reprinted, nor were her works included in eighteenth-century vocal anthologies. Between 1782 and 1797, eight of Turner’s songs appeared in the Lady’s Magazine, sometimes more than once. Her music had been out of circulation for decades when Hudson incorporated her songs into the periodical, possibly to present the example of a woman composer to the magazine’s many female readers. Turner’s creative voice was effectively silenced until her remarkable second life in the pages of the Lady’s Magazine.

Musical Example 15.3 Alcock, “On Music,” Lady’s Magazine 12 (December 1781).

The songs came from Turner’s 1756 Collection of Songs with Symphonies and a Through Bass with Six Lessons for the Harpsichord.42 “Phillis with Her Enchanting Voice”—Song VI from the collection—was the first of Turner’s songs published in the Lady’s Magazine, inserted in July 1782 and again in 1786 and 1795.43 The anonymous poetry “by a Lady” expressed typical pastoral sentiments, but Turner’s setting was elegant and melodious, as seen in the phrases that begin the first stanza (musical example 15.4). With its ornamental graces for harpsichord and voice, the song was an antique in the stile galant of three decades earlier. Hudson omitted the figured bass indications from Turner’s songs in the magazine, and the eight-measure keyboard introduction disappeared in the 1786 and 1795 reprints, but the lyrical flow of the vocal line and the smooth counterpoint between treble and bass remained intact. Her songs exemplify the English tradition of deceptively simple, tuneful melodies in repeated halves, rather than the typical da capo form of Italian opera arias.

Musical Example 15.4 Turner, “A Song, the Words by a Lady; and Set to Music by the Late Miss E. Turner,” Lady’s Magazine 13 (July 1782), mm. 9–20.

Turner is one of the composers found most often in the periodical after Handel and Hudson. By reprinting her songs, Hudson honored and perpetuated the memory of a respected fellow musician as he did for such colleagues as Boyce and Howard.44 Through Hudson’s efforts, the Lady’s Magazine embraced not only a range of repertoires, but also contained the most serious and historic music of any literary miscellany in eighteenth-century Britain. Hudson’s replacement, William Barre Jr., didn’t abandon the historical approach, but he failed to retain his predecessor’s success.45 Barre’s songs were numerous in the Lady’s Magazine during 1801 and 1802, but music publication in the Lady’s Magazine terminated abruptly during 1805 and never resumed as a monthly feature. This change followed a trend as fashion and domestic skills eclipsed education in the magazine and as sentimental fiction replaced historical or moral essays. But new English periodicals for women—the Ladies’ Monthly Museum (1798–1832) and La Belle Assemblée (1806–1837)—carried the tradition of music inserts into the Regency period after the dowager Lady’s Magazine discontinued the practice.46

In an era when fashions came and went with each season, Hudson’s thirty-year legacy of music in the Lady’s Magazine was no small achievement. Through the agency of the Lady’s Magazine, Hudson relocated selected public musics into the drawing room and allowed nonprofessional music lovers to perform some repertoire that career musicians staged in British centers of culture and privileged male amateurs enjoyed in semiprivate societies. Rarely a mere embellishment, music in the Lady’s Magazine intertwined pleasure with pedagogy, partaking of both public and private as the magazine mingled historical with musical streams from the city venues of concert stage, theater, pleasure gardens, and recreational music clubs for the consumption and education of magazine enthusiasts and listeners.

Named or confirmed composers of music published in Robinson’s edition of Lady’s Magazine, 1770–1805, with number of occurrences, year(s), and specific sources (oratorio, ode, opera, play, masque) as identified in the Lady’s Magazine.

Alcock, J[ohn], younger (ca. 1740–1791)

1: 1781

Arne, Dr. Thomas A[ugustine] (1710–1778)

5: 1789-2 (Alfred, Eliza); 1802 (Alfred); 1804 (As You Like It); 1805 (Abel)

Baildon, Mr. [Joseph] (1727–1774)

3: 1775-2; 1788

Barre, William, junior (fl. 1790–1805)

37: 1791; 1794; 1800-2; 1801-5; 1802-8; 1803-10; 1804-6; 1805-4

Bates, William (ca. 1720–1790)

1: 1794

Boyce, Dr. [William] (1711–1779)

7: 1782-4; 1789 (Solomon); 1797 (The Chaplet); 1798 (The Chaplet)

Brewer, Thomas (1611–ca. 1665)

1: 1790

Chapman, Richard, of Portsmouth

1: 1777

Chard, George (1765–1849)

1: 1783

Corri, D[omenico] (1746–1825)

1: 1805

Finch, Miss

1: 1804

Ford, Thomas (ca. 1580–1648)

1: 1789

Giardini, [Felice] (1716–1796)

1: 1800

Gidley, C.

1: 1775

Gluck, [Christoph Willibald von] (1714–1787)

1: 1775 (Iphigénie)

Greene, Dr. [Maurice] (1696–1755)

10: 1775; 1786; 1794-3; 1795-5

Handel, Mr. [George Frideric] (1685-1759)

107: 1776-4 (Jephtha, Semele, Samson, Judas Maccabaeus); 1777-2 (Judas Maccabaeus, Susanna); 1778-5 (Judas Maccabaeus, Esther, Joshua, Hercules, Theodora); 1779-4 (Alexander Balus, Acis and Galatea, Occasional Oratorio); 1781–2 (Saul, Samson); 1782-2 (Choice of Hercules-2); 1783 (Deborah); 1784-3 (Messiah, Samson, Semele); 1785-7 (L’Allegro, il Penseroso, ed il Moderato-2, Deborah, Alexander Balus-2, Saul, Samson); 1786-4 (Saul, Occasional Oratorio, Susannah-2); 1787-10 (Deborah, Occasional Oratorio, Alexander’s Feast, Hercules, Judas Maccabaeus, Saul, Susanna, Semele, Additional Oratorio, Time and Truth); 1788-5 (Jephtha, Alexander Balus, Messiah, Joseph); 1789-6 (Messiah-2, L’Allegro-3, Esther); 1790-7 (Messiah, Alexander’s Feast, Solomon, Redemption); 1791-7 (Occasional Oratorio, Acis and Galatea-2, Semele, Esther; Theodora, Saul); 1792-6 (Saul-2, Susanna-2, Alexander Balus); 1793-10 (Susanna-2, Dryden’s Ode, Judas Maccabaeus-2, Esther, Theodore, Jephtha-2, Saul); 1794-5 (Occasional Oratorio-2, Joshua, Semele, Saul); 1795-2 (Saul, Deborah); 1797-3 (Judas Maccabaeus, Alexander’s Feast, Joshua; 1798-6 (Saul, Solomon, Susannah, Choice of Hercules, Occasional Oratorio); 1799-2 Hercules, Susanna); 1800-2 (Alexander Balus); 1805-2

Hawkins

1: 1780

Hawkins, Captain A., of the North Devon Regiment

3: 1783-2; 1788

Haydn, [Franz Josef] (1732–1809)

1: 1800

Henly, Mr. Rev. [Henley, Phocion] (1728–1764)

1: 1778

Hilton, Mr. [John, younger] (ca. 1599–1657)

2: 1775-2

Hoare, Mr. R.

1: 1776

Hodgson, Mr. Philip, of Newcastle

10: 1773-3; 1774-2; 1775-2; 1776; 1777-2

Howard, Dr. [Samuel] (1718–1782)

14: 1782-2; 1793; 1796-2; 1798; 1799-8

Hudson, Mr. [Robert] (1732–1815)

142: 1770-5; 1771-14; 1772-9; 1773-7; 1774-9; 1775-6; 1776-4; 1777-4; 1778-4; 1779-6; 1780-10; 1781-8; 1782-2; 1783-4; 1784-5; 1785-4; 1786-2; 1787-2; 1788-6; 1789-1; 1790-2; 1791-2; 1792-2; 1793-1; 1795-5; 1796-7; 1797-4; 1798-5; 1799-2

Ives, Simon (1600–1662)

1: 1784

King, Mr. C[harles] (1687–1748)

1: 1775

Laws [Lawes], William (1602–1645)

1: 1794

Major, Joseph (1771–1829)

1: 1804

Martini, Vincenzio [Vicente Martin y Soler] (1754–1806)

1: 1801

Morgan, Mr.

1: 1773

Morley, Thomas (1557–1602)

5: 1775; 1776; 1783; 1792; 1794

Mozart, [Wolfgang Amadeus] (1756–1791)

2: 1800-2

Pring, Joseph, late chorister of St. Paul’s Cathedral

1: 1792

Purcell, Henry (1659–1695)

3: 1786; 1787; 1792

Ravenscroft, Mr. [Thomas] (ca. 1592–ca. 1635)

2: 1790-2

Reichardt, [Johann Friederich] (1752–1814)

2: 1801

Reynolds, Mr.

1: 1797

Rogers, Dr. [Benjamin] (1614–1698)

2: 1786; 1789

Scarlatti [sic]

1: 1804

Shaw, Mr., of Bath

1: 1777

Shield, Mr. J[ohn], Jr.

4: 1780; 1781; 1784; 1791

Shield, Mr. William (1748–1809)

9: 1774-2; 1778-2; 1801; 1802; 1803; 1804; 1805

Shield, Mr. [William?]

7: 1783; 1784; 1786-2; 1800-2; 1801

Stone, J., Organist at Marlborough; Organist of Farringdon, Berks.

8: 1777; 1778; 1779-3; 1780; 1796-2

Tenducci, Seignior [sic; Giusto Ferdinando] (ca. 1735–1790)

1: 1800

Travers, John (ca. 1703–1758)

4: 1775; 1786; 1789; 1792

Turner, Miss Eliza[beth] (d. 1756)

13: 1782-2; 1783; 1784; 1785; 1786; 1788; 1795; 1796-2; 1797-3

[Weelkes, Thomas] (1576–1623)

1: 1790

Wright, T[homas], of Stockton-upon-Tees (1763–1829)

1: 1791

1. The Lady’s Magazine adopted large, folding music inserts like those included with the Court Miscellany (London, 1765–1771). Since the oversize inserts were not secured in the monthly issues, the music is frequently missing or misbound in library holdings. The most satisfactory source to see music in the Lady’s Magazine is the microfilm series Women Advising Women, Part 3 (1770–1800) and Part 4 (1801–1832), based on holdings from the British Library, Cambridge University, and Birmingham Central Library. While the music supplement sheets are often missing, the song inserts have been photographed in full in Women Advising Women. Music leaves have not been opened and scanned in the digitized volumes of Lady’s Magazine available in the HathiTrust Digital Library, Europeana Collections, and Google Books.

2. The music sheets were not copperplate engravings, but typeset for the magazine, with frequent errors, by the London firm of Bigg & Cox. “Omrah Restored” was a short story set in the Middle East.

3. After 1832, the magazine continued as The Lady’s Magazine and Museum of Belles Lettres, then as The Court Magazine and Monthly Critic, and Ladies’ Magazine and Museum of Belles Lettres from 1838 to 1847.

4. Batchelor, “‘Connections which Are of Service,’” 247. See also Adburgham, Women in Print, 128–158, and Marks, “Lady’s Magazine, The.” The University of Kent is conducting a research project titled “The Lady’s Magazine (1770–1818): Understanding the Emergence of a Genre,” with website http://blogs.kent.ac.uk/ladys-magazine/category/content/, accessed August 15, 2015. An index of music in the magazine prepared by me will appear as part of this project.

5. See Ritchie’s chapter 2, “Women’s Occasion for Music,” in Women Writing Music, 57–86.

6. Miller, “A Mirror of Ages Past,” 883–901. The term magazine music was in occasional use by the mid-nineteenth century, as in Sartain’s Union Magazine of Literature and Art, 8 (1851): 133. The data on magazine music cited throughout this essay comes from the author’s index of music in British monthly miscellanies to 1800, based on collections at preeminent British, Irish, and American libraries; microfilm series English Literary Periodicals, Early British Periodicals, Women Advising Women, Early English Newspapers, History of Women; and subscription databases Eighteenth Century Collections Online, British Periodicals Collection I and II, and Eighteenth Century Journals.

7. Laurie and Price, “Motteux, Peter Anthony,” GMO (accessed November 27, 2013). See also “Index to the Songs and Musical Allusions in The Gentleman’s Journal, 1692–4”; and Radice’s “Henry Purcell’s Contributions to The Gentleman’s Journal, Part I,” and “Henry Purcell’s Contributions to The Gentleman’s Journal, Part II.”

8. Barker, “Cave, Edward (1691–1754),” DNB (accessed May 2, 2014). See Italia, The Rise of Literary Journalism in the Eighteenth Century, 110–122.

9. By contrast, the essay serial or periodical essay contained the work of one author, often with a political slant, such as Joseph Addison’s and Richard Steele’s Spectator (1711–1714). Reviewing journals such as the Monthly Review (1749–1844) published abstracts and excerpts of scholarly or scientific material from learned books.

10. A note below the music for “The Charmer” stated, “N.B. This SONG is inserted by Desire,” presumably meaning by request of a reader, in Gentleman’s Magazine 7 (1737): 626.

11. Few earlier serials written for or by women, such as The Female Tatler (1709–1710) and The Lady’s Curiosity (1738), lasted more than a season or two. See Adburgham’s chronological list in Women in Print, 273–281.

12. Fitzpatrick, “J. Coote,” 57–65.

13. Coote sold the magazine to George Robinson and John Roberts in April 1771, without informing John Wheble, who continued to print monthly issues. The court decided for Robinson but permitted Wheble to continue his edition of the magazine, which lasted until the end of 1772. See Batchelor, http://blogs.kent.ac.uk/ladys-magazine/tag/john-wheble/ (accessed August 15, 2015).

14. Front matter, Wheble’s Lady’s Magazine 3 (1772).

15. Ritchie, Women Writing Music, 11.

16. Ibid., 81–86.

17. Picard, describing songs in the Gentleman’s Magazine, in Dr. Johnson’s London, 245; and Head, “Music for the Fair Sex,” 244.

18. Opinion regarding music study by boys was codified in the Earl of Chesterfield’s letter of April 19, 1749, warning his son not to play an instrument, as it was “frivolous, contemptible, and takes up a great deal of time, which might be much better employed” (Stanhope, Letters to His Son by the Earl of Chesterfield, vol. 1, 170).

19. Essex, The Young Ladies Conduct, 85.

20. The vicar choral was a layperson who chanted portions of the liturgy. Hudson was honored for his long service by internment in St. Paul’s. Husk and Gifford, “Hudson, Robert,” GMO (accessed September 17, 2007). See Spink, “Music, 1660–1800,” 392–398; Dawe, Organists of the City of London, 5–7.

21. The appendix does not include the music sheets from April 1771 until the end of 1772 in the edition of the Lady’s Magazine printed by Wheble (see endnote 13).

22. Many Lady’s Magazine songs were reprinted in Alexander Hogg’s pirated imitation, the New Lady’s Magazine; Or, Polite and Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex (London, 1786–1795). Songs in Hogg’s periodical were newly typeset on regular magazine pages that are rarely absent from library holdings; thus, the copycat magazine provides music sometimes missing from volumes of Lady’s Magazine.

23. The Joly Collection at the National Library of Ireland and the Harvard Theatre Collection contain many song sheets taken from London miscellanies. Jane Austen’s music books lack any song sheets extracted from the Lady’s Magazine, although there is some overlap of titles by Handel (Gammie and McCulloch, Jane Austen’s Music).

24. Examples include “Total Eclipse” from Samson and “Angels Ever Bright and Fair” from Theodora.

25. The annual “Directions to the Binder” indicate that music was to be bound in or near the poetry section, but song sheets were sometimes placed at the beginning or end of the monthly issue or annual volume.

26. Like her husband, Mrs. Hudson sang at the pleasure gardens, and their daughter, Mary Hudson (ca. 1758–1801), worked as a musician and organist in London (St. Olave Hart Street) from 1781 until her death (Dawe, Organists of the City of London, 4; Robins, Catch and Glee Culture, 49–50). Mr. Hudson and Miss Hudson were listed as chorus members for the Handel commemoration concerts in Burney’s Account of the Musical Performances in Westminster-Abbey and the Pantheon, 19–20.

27. Bennett, Letters to a Young Lady, vol. 1, 151.

28. Vocal music from the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries was cited as “ancient music” by the Academy of Vocal Musick in 1726, later called the Academy of Ancient Music. In 1776, the “Concert of Antient Music” broadened the practice to include music composed more than twenty years earlier. Tim Eggington traces the historical movement in The Advancement of Music in Enlightenment England.

29. Burney, “Effects of Ancient Music,” Lady’s Magazine 7 (1776): 81–84, 126–129, and 206–209. Hawkins, “Anecdotes of Mr. Handel,” Lady’s Magazine 7 (1766): 699–700. Hawkins, “On the Marvellous Power and Effects of Ancient Music,” Lady’s Magazine 9 (1778): 321–323, 510–512, and 707–711. See also Aspden, “Disseminating and Domesticating Handel,” this volume.

30. Hudson also composed hymns and liturgical music, but the majority of entries in the British Library Catalogue of Printed Music are items located in, or extracted from, the magazine.

31. Hudson, “Thyrsis,” Lady’s Magazine 16 (1785), following p. 664 in Women Advising Women microfilm, Part 3, reel 8.

32. Hudson published three undated sets titled The Myrtle, the third of which specified, “A Collection of Songs sung at Ranelagh.” “Love at First Sight” was presented in The Myrtle, both as a solo air, 11–12, and duetto, 13.

33. Hudson rarely included figured bass in the Lady’s Magazine after 1790. Song sheets with figured bass had been common in literary miscellanies, and figures can be seen as late as the 1790s, as in “Urbani’s Celebrated Rondeau,” Aberdeen Magazine 4 (1791): 499–501.

34. Significant errors occur in “Thyrsis” from Lady’s Magazine when compared to “Love at First Sight” in The Myrtle, digitized from GB-Lbl G.806.g.(13) in the Petrucci Music Library at www.imslp.org. The magazine imprint has A-flat in the treble in m. 14 (“when”), but “Love at First Sight” uses E-flat, as in the opening ritornello. The treble in “Thyrsis” uses A-natural in m. 28, when “Love at First Sight” has A-flat. The bass in m. 31 of “Thyrsis” begins with A-flat, resulting in parallel fifths with the treble, whereas the bass resolves upward to E-flat in “Love at First Sight.”

35. Hudson, “Song on Nelson’s Glorious Victory,” Lady’s Magazine 29 (1798), following p. 472 in Women Advising Women, Part 3, reel 14.

36. Robins, “The Catch and Glee in Provincial England,” 147–148.

37. Alcock, “On Music,” Lady’s Magazine 12 (1781), following p. 664 in Women Advising Women, Part 3, reel 6.

38. Rubin, English Glee in the Reign of George III, 196.

39. The other example definitely composed by a woman was “The Negro’s Complaint . . . Music by a Female Correspondent—an Amateur,” Lady’s Magazine 24 (1793). The attribution in August 1804, “A Patriotic Song. By Miss Finch,” could refer either to the music or to the poetic text.

40. Yelloly presents the known facts and social context in “‘The Ingenious Miss Turner,’” 72–75.

41. Yelloly discusses Turner’s subscribers, ibid., 68–69, as does Ritchie, Women Writing Music, 66–76.

42. Turner’s 1756 collection can be viewed in the Petrucci Music Library at www.imslp.org.

43. Turner, “A Song,” in Lady’s Magazine 13 (1782), following p. 368 in Women Advising Women, Part 3, reel 6; “Song,” in Lady’s Magazine 17 (1786), following p. 380 in Women Advising Women, Part 3, reel 8; and “Song for the Lady’s Magazine,” in Lady’s Magazine 26 (1795), following p. 432 in Women Advising Women, Part 3, reel 13. The 1795 song sheet is available in the HathiTrust Digital Library, accessed August 15, 2015.

44. While elegiac poets had stressed her beauty, voice, and virtue, Hudson included her songs without comment, thereby granting Turner the same respect that he extended to male colleagues, rather than following “the cult of the beautiful dead,” described by Head in “Cultural Meanings for Women Composers,” 231 and 233.

45. He was probably the William Barre who entered psalm and hymn tunes at Stationers’ Hall in 1800 (Kassler, Music Entries at Stationers’ Hall, 437 and 442).

46. La Belle Assemblée contained regular music sheets from 1806 and Lady’s Monthly Museum from 1816.