REMARKABLE PEOPLE TEND TO BE focused; it tends to go with the territory. But no one, and I do mean no one, is more focused than Mickey Hart, drummer of the Grateful Dead, the seminal psychedelic rock band from the 1960s to the present day. Mickey’s ‘thing’ is rhythm. And he is all in.

On the occasion our paths first cross, I hear him before I see him. There’s a beat – a knocking, tocking sound – and a haunting wail coming from a secluded, fire-lit corner in this remote part of the Guatemalan Highlands where we’re staying.

Intrigued, I move towards the beat and find Mickey, cross-legged on the floor, eyes closed, gently swaying in front of the fire, with four Mayan shamans blowing, shaking and hitting their traditional ceremonial instruments, the same ancient rhythms and noises the Mayans have been making among these rainforest-clad hills for millennia. And Mickey is feeling it.

He’s flown into this far-flung spot to jam with the shamans in his never-ending search for new sounds and beats. This is what he does. He does rhythm.

To put this into context, this is a man who has a specially built lab at home in which he sits wearing his own specially built rhythm helmet, a device wired up to an MRI scanner to measure the effect on his brain of the different beats he plays. This is the same man who has worked with NASA to listen to the rhythm of the universe, recording the distant beats and rumbles from remote galaxies, describing the Big Bang as ‘the first note, the downbeat of the universe’. It’s all pretty cosmic, in every sense of the word, but these are serious endeavours. His latest project has him working with doctors on a study of the effect of different rhythms on disease: are there certain frequencies that can affect unhealthy cells and help them? If anyone can find out, it’s Mickey.

His advice, therefore, came as no surprise.

‘If I was to give one piece of advice, it is this: life is all about rhythm. Your heartbeat, great sex, the seasons, how often you call your parents, your good days versus your bad days, your DNA, the universe: everything has a rhythm. You have to develop a well-stretched ear and listen. The more you listen for the rhythm of your life, the more you will hear it. Find your rhythm. Live your life to its beat.’

But for now he is back with the shamans. They’re still playing in their trance-like state, summoning past ancestors, gods and monsters. Mickey is reverential to the shamans and respectful of their traditions, but he’s also a perfectionist. To his ear, something’s not quite right, something’s a little off. It’s the conch shell. Or more specifically it is the way the conch shell is being blown. Mickey knows a better way. He stops the proceedings, explains via the translator the nature of the issue, and in one short blast Mickey improves on 5,000 years of technique. The shamans look impressed.

‘FIND YOUR RHYTHM. LIVE YOUR LIFE TO ITS BEAT.’

– Mickey Hart

HAVING WORDS WITH CLARE BALDING

I THINK I’VE JUST BEEN CALLED a ‘beta male’. I’m with Clare Balding and we’re talking about gender equality and she said that the growth of the beta male is a positive thing, and looked approvingly at me. I’m not quite sure how I feel about being seen as one. I think I may secretly like it, which, if so, basically proves her assertion. And presumably makes her alpha female, at least in this conversation.

Certainly when it comes to presenting Clare Balding takes first place, no contest. She’s been in front of the camera at six Olympic Games, five Paralympics, three Winter Olympics, two Wimbledons, countless horse-racing events and a never-ending stream of TV shows and radio programmes. Add to that a best-selling memoir, constant public speaking and a new kids’ book, and you get the sense of an ambitious woman who works as hard as the athletes she interviews.

When the word ‘ambition’ comes up, it gives rise to a moment of reflection. ‘It’s funny, I have had so many old-fashioned newspaper critics write, “She’s very ambitious”, as if it’s negative because I am a woman. But I think, “Too bloody right I’m ambitious, why shouldn’t I be? Should I want to come second?”’

Sexism is unfortunately nothing new to Clare. She’s been exposed to it since the day she was born, quite literally. ‘My grandmother took one look at me in the crib and said to my father, “Oh, it’s a girl. Never mind, you’ll just have to keep on trying.”’ That set the tone for a family life in which Clare was constantly told women can’t do certain things and should behave in a certain way. Fortunately, it had the opposite effect and she’s been proving them wrong ever since.

A background radiation of homophobia is another thing she has had to grow used to. ‘A lot of people throw stones at me on social media and a lot of those stones are labelled “dyke”.’ It took her seven years to come out to her parents, because ‘I was so concerned about the shame of it, but I eventually woke up to the fact that I was complicit in the shame.’ Her advice to anyone in the closet is to get out of it damn quick. ‘You’re not protecting yourself and you’re not protecting others, you are in fact protecting the prejudice. Be proud, not ashamed.’ And she is optimistic that the world is becoming increasingly accepting of the LGBT community, recounting a sweet conversation she had recently with her five-year-old niece. ‘She said to me, “You’re married, aren’t you, Aunty Clare?” I said, “Yes, I am,” and she said, “So girls can marry girls and boys can marry boys?” I said, “Yes, they can.” And she said, “Well, that’s good, isn’t it?” So for this generation it will always have been normal.’

As well as the ambition and optimism, you also get the sense of a woman who is perpetually interested. It is in fact one of the main pieces of advice she passes on: ‘everything you do is an opportunity to learn, every person has a story to tell, if you think someone is dull it is because you’re asking the wrong questions’. With a natural curiosity, she has found her true vocation in a career that involves researching, interviewing, presenting.

She takes the gig seriously, and is rightly respected for having won every gong that’s going for presenting. In her view, it’s about helping the viewer experience at home what she is experiencing being right there in the middle of the action. ‘It is almost creating a virtual reality but without the glasses.’ To be able to do so, according to Clare, you have to remove all ego: it is never about the presenter, but about what is going on around you. The other critical thing is vocabulary. You need to build evocative sentences easily and quickly. Her trick for that is to read a lot of literature, especially poetry, so she has the language to hand to bring what she’s seeing to life in words.

Maybe it is a coincidence, but her most valuable piece of advice is about words, in this case specifically adjectives:

‘In life, we are not what we look like, we are not our gender, sexuality or religion or race, we are how we act and the impact that we have on others. And the best way to think about the impact we have on others is in adjectives. I ask myself “What person do I want to be?” But in adjectives, not nouns. How about kind? Healthy? Ambitious? Does thinking like that get me to a more fruitful and satisfying place? I think it probably does.’

It’s an original way of thinking about personal growth and leaves me with just one question: is ‘beta’ an adjective?

‘I’VE HAD OLD-FASHIONED NEWSPAPER CRITICS WRITE, “SHE’S VERY AMBITIOUS”, AS IF IT’S NEGATIVE BECAUSE I AM A WOMAN. BUT I THINK, “TOO BLOODY RIGHT I’M AMBITIOUS, WHY SHOULDN’T I BE? SHOULD I WANT TO COME SECOND?”’

– Clare Balding

NANCY HOLLANDER, JIU-JITSU LAWYER

I’M SITTING DRINKING PEPPERMINT TEA with David, Goliath’s nemesis. But David is not how I expected him to be. Firstly, he is a woman. Secondly, she’s American. And finally, she’s petite and seventy-two.

You have probably not heard of Nancy Hollander, which is a good thing for you personally. As an American criminal defence and civil rights attorney, you’d only come across her if you were, rightly or wrongly, in trouble. But without her, there is a dark part of the world we would know a lot less about: Guantánamo Bay.

Nancy Hollander is the lawyer of two of the men incarcerated in that prison, set up on foreign land by the US government under the Bush administration. It did so, seemingly, with the deliberate aim not to just imprison men they suspected of terrorist activity, but to do so indefinitely, unaccountably, with no charge but with plenty of torture, and in direct contravention of constitutional and human rights. However, if Nancy knows one thing, it is that the law is bigger than the government. So she is fourteen years into a legal fight on behalf of her clients to get the US government to abide by its own laws. It is a painfully slow battle but one she is starting to win.

As a master strategist, she engineered a tactical success by winning the right for one of her clients, Mohamedou Ould Slahi, to publish his Guantánamo Diary, a memoir recounting the extraordinary rendition, dark sites, savage beatings, torture and sexual humiliation he has experienced during his fourteen years in captivity. It made uncomfortable reading, especially for the American government. The furore around the book helped to bring attention not just to the abuses but also to the reality of Mohamedou’s situation, that he had been held in Guantánamo Bay for well over a decade, uncharged with any crime, and even after the former chief prosecutor in Guantánamo had said publicly there was no evidence that Mohamedou ever committed any violence against the United States.

His case, or lack of one, has been a troubling manifestation of the illegal practices that Nancy constantly fights.

But in this case she has fought successfully: after nearly a decade, and as this book goes to print, she has just obtained approval for his release, although an actual date is still to be given. Her work continues.

In conversation, Nancy is absolutely focused on due process. She will not reveal a single piece of potentially classified information about any of her clients or the conditions in which they are held, even if that information is already in the public sphere. She will not do anything that could potentially give the US government opportunity to undermine her or her achievements to date. Her one action outside formal procedure is the metal kangaroo badge permanently pinned to her lapel, a silent protest of the ‘kangaroo court’ style of justice her clients are being subjected to.

As a young woman growing up in Texas in the 1950s, she was no stranger to injustice. Aged ten, she was the only student in a class debate to support the Brown vs Board of Education court case that said segregated public schools were unconstitutional. Her teachers rang her parents to say they were worried about her for being so strident. But as ‘intellectual lefties’ they supported her. At age seventeen she would follow police paddy wagons around Chicago at night, taking photos of cops beating up people. She has been arrested on three separate occasions for peaceful protest and has spent her entire life fighting for people’s rights, irrespective of what they may or may not have done. She may be a small woman, but she stands tall and resolute in front of power.

What comes out in our conversation is that Nancy is an avid practitioner of martial arts, and jiu-jitsu in particular, and she uses the principles taught by her sensai in taking on opponents much bigger than herself:

‘Whatever you do, do it with intent. In martial arts we call it “one plus one”. Just one good kick and one good punch is better than twenty you didn’t have any intent behind. Do not say something unless you mean it, do not do something unless you are committed. Do not confront by shouting, but confront by using your intellectual powers and the power of a better argument, by standing your ground, by keeping your centre, by never transgressing so they cannot attack. Ultimately, the trick is to absorb and redirect their energy. You use their own power against themselves.’

None of this is at small cost to herself. Her tireless work has meant she’s been accused of being a terrorist sympathiser or a flat-out terrorist, purely for her insistence that the government follows its own constitution and prosecutes people fairly. She says that the people who have criticised her the most savagely have been those within, or connected to, the Bush administration. Which she says is ironic, as they are the ones who, by falsifying reports, condoning torture and signing off on extraordinary renditions, have been breaking the law. And who, therefore, one day may need her services most.

Absorb and redirect indeed.

‘WHATEVER YOU DO, DO IT WITH INTENT. JUST ONE GOOD KICK AND ONE GOOD PUNCH IS BETTER THAN TWENTY YOU DIDN’T HAVE ANY INTENT BEHIND. DO NOT SAY SOMETHING UNLESS YOU MEAN IT, DO NOT DO SOMETHING UNLESS YOU ARE COMMITTED.’

– Nancy Hollander

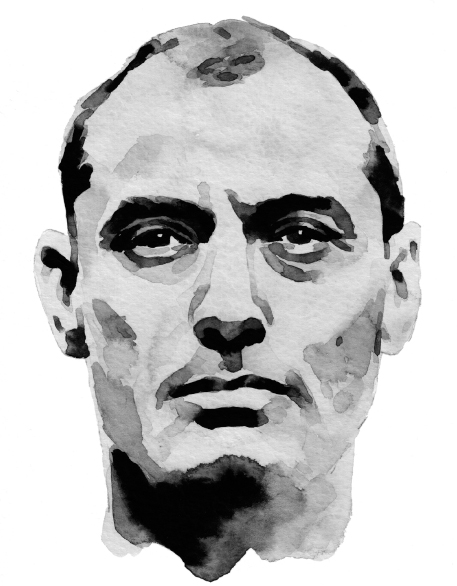

ON THE DAY WE MEET, time is running out for Jude Law. Not in respect to life generally, but on his parking meter. To avoid the faff of finding loose change and re-parking, we decide to sit and talk in his car, pulled up on the side of Shaftesbury Avenue, a kind of poor man’s Carpool Karaoke.

We chat about our respective childhoods. I mention I grew up in Huddersfield, and to my surprise Jude says he’s going there at the weekend. No disrespect to my hometown, but it’s not normally a place where international movie stars go to hang out. When I enquire what takes him there, he explains it is to meet with the uncle of a young Syrian boy who Jude befriended when he visited The Jungle, the makeshift refugee camp in Calais. The child-refugee in question had seen his mum, dad and siblings die in the crossing from Africa and was in the camp all alone, so Jude offered to pay the legal fees and oversee the process of getting him out of the camp and into the arms of his one remaining family member up in Huddersfield.

The fact that Jude went several times to the refugee camp in the first place, is doing all this personally for the young lad, and, most tellingly, it only comes up in conversation because of an unlikely coincidence says a lot about the guy off screen.

In fact, Jude Law has a long history of going the extra mile to support important causes. On previous occasions he travelled to the Democratic Republic of the Congo and to Afghanistan with the peace-making organisation Peace One Day; he was part of an initiative that managed to broker a twenty-four-hour ceasefire agreement between the Taliban and the American military in Afghanistan, the result being that during the brief cessation 10,000 health workers were mobilised and inoculated 1.4 million children.

He puts his track record of stepping out of the limelight and into pretty tough places down to several things. One is to make sense of this strange thing called fame. ‘I’m in no way comparing myself to him, but my hero John Lennon said, “If you’re going to poke a camera in my face, then I am going to say something important.” That’s the worth of media and fame, to help important things get noticed.’ He also says if he were to stick to just the movie-star life of five-star hotels and VIP experiences then he would ‘feel fat with guilt’. On the most basic level he has a curiosity about the world and a desire to engage with as many different aspects of it as possible. His perspective is essentially, ‘Why wouldn’t you want to go to these places?’

This ethos of experiencing life for its own sake is echoed in his advice for people who want to make it as an actor. ‘There is such a large amount of luck needed to get your moment, so you have to be in acting for the right reasons: do it because you love the thing, the process, because you’ll enjoy doing a no-pay play in a room above a pub. You have to be happy doing it that way, because what happens otherwise if you don’t get your break?’ He says it is having that love of the actual thing that will keep you sane if you do make it because otherwise ‘it can fast start to feel like a business and you will need to keep that original flame alight or you can lose your way’.

When I ask for his single best piece of wisdom, we revert back to talking about his childhood, and he credits his dad with his favourite piece of advice, given to him as a young boy:

‘If you are going to be late, enjoy being late.’

It was a piece of advice he meant literally: that if you are late, rather than panic and get stressed, enjoy the extra time it is affording you. But as a piece of advice it has served Jude as a wider metaphor for life, reminding him to ‘relish the moment, be in the moment, do the right thing in the moment, whatever that moment is’, be it in a refugee camp, a room above a pub or the set of your latest blockbuster.

And with that, he has to go. He’s running late.

‘If you are late, enjoy going to be being late.’

– JUDE LAW

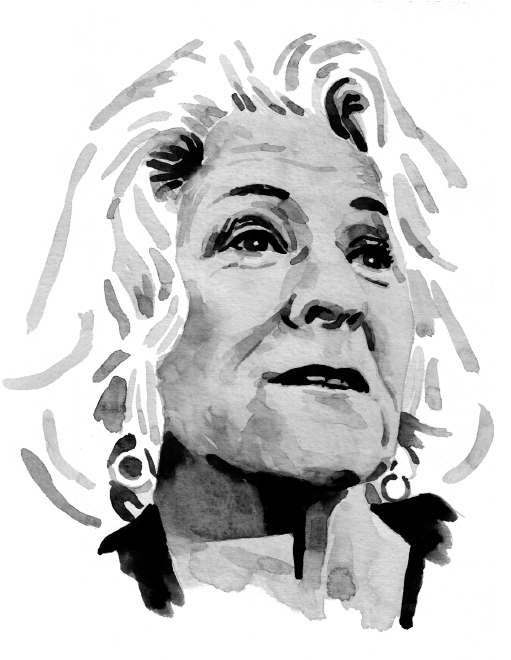

PILLOW TALK WITH JOAN BAKEWELL

AGED EIGHTY-THREE, JOAN BAKEWELL, THE much-loved BBC presenter, writer and member of the House of Lords, is a woman who has no time for getting old. Not only is she too busy to pay it any regard, she simply rejects the whole concept of it in the first place. ‘I don’t believe in the so-called declining years. Every day is a full twenty-four hours, with sixty minutes in each hour, and it is the same amount of time whether you are twelve, twenty, forty or eighty. You’re getting as much daylight as anyone else and the same amount you’ve ever got. It’s up to you what you do with it.’

We’re having this conversation in her bookish town house set in the corner of a leafy North London square. And when I say bookish, I mean it literally. Books really are everywhere. ‘I know, I’ve got so many of the damn things.’ She tells me she has a solution. Every Saturday and Sunday she has started putting a box outside her house of the books she’s read and passers-by help themselves. It’s a solution that neatly matches her career of spreading ideas and putting things out there.

In conversation, Joan comes across as a woman with her yin and yang right where she wants them. She talks about the two lives we each have – our inner life, which comes alive ‘when you’re walking alone or sitting quietly or listening to a piece of music’, and our outer life, when ‘you’re going, hello world, here I am, I’m doing lots of things, watch me do them’. And she has found that it’s better to ‘let the inner life lead, and let the outer life conform to it’.

She’s specifically talking about what she calls the ‘hunches within us’, deep-seated urges that can guide us to what we will find most gratifying. ‘People look for good jobs with good hours and pensions, and none of that is going to be relevant to how you feel about your life. It really isn’t.’ She counsels that life is more nourishing if we follow our instincts instead.

But we have to listen carefully for this quieter, inner guide. To this end, she advocates deliberately making the time and space to let such voices be heard. She tells me that she has recently come back from a month by herself in a tiny one-bedroom cottage, to just write and spend time with herself. ‘While I was there my social life consisted of walking to the stream at the bottom of the garden. Most of us are normally choked with activities, so bouts of solitariness can be very rewarding.’ Building in such time to just be means that ‘really extraordinary things can crop up in your head that you didn’t know were there, sort of like waking dreams, fantasies, ambitions. They come out of somewhere that is pre-language, and finding your way back to that place is very important. Once you start articulating ideas in words you’ve already lost some of the options.’

It’s surprising to hear someone who is professionally eloquent recommending getting back to a pre-language, wordless state, but she says it is a characteristic of anyone creative she’s ever known. And she believes we all benefit from allowing time for things to settle, ferment and rise to the top. ‘The answer to most people’s problems tend to be embedded somewhere inside themselves already and will make themselves felt if given the opportunity to.’

The one counter point she makes to the importance of our inner guide is that you have to keep an element of critique as well. There should be no self-delusion; you need to be clear-sighted about what you can and cannot do. And there also has to be, at some point, action. She is not advocating spending the rest of your life daydreaming by the stream at the bottom of the garden.

The advice she passes on reflects this view on life and is the same advice she has always given her children:

‘If you put your head on a pillow late at night and think it hasn’t been a good day, wake up next day and change something. It might be your ideas or attitude, it might be to leave a job or husband. It could be anything, but change something. Don’t just drag on a set of circumstances which just aren’t falling into the right places. You’ve got to listen to and then act on that inner spark.’

It’s an approach that taps into her first point about ageing: if you nourish your inner self and act in line with it, ‘you can go on being as fruitful and as full of ideas as the day is long. You’re only declining if you think you are.’

She cites Robert Plant, her neighbour, as an unexpected inspiration in this regard. ‘He’s fantastic, incredibly productive, and he’s sensational to look at too, very rugged, like Mick Jagger, and with this incredible hair. He’s showing no signs of these so-called declining years at all.’

And neither, it has to be said, is Joan Bakewell.

‘IF YOU PUT YOUR HEAD ON A PILLOW LATE AT NIGHT AND THINK IT HASN’T BEEN A GOOD DAY, WAKE UP NEXT DAY AND CHANGE SOMETHING. IT MIGHT BE YOUR IDEAS OR ATTITUDE, IT MIGHT BE TO LEAVE A JOB OR A HUSBAND. IT COULD BE ANYTHING, BUT CHANGE SOMETHING. DON’T JUST DRAG ON A SET OF CIRCUMSTANCES WHICH JUST AREN’T FALLING INTO THE RIGHT PLACES. YOU’VE GOT TO LISTEN TO AND THEN ACT ON THAT INNER SPARK.’

– Joan Bakewell

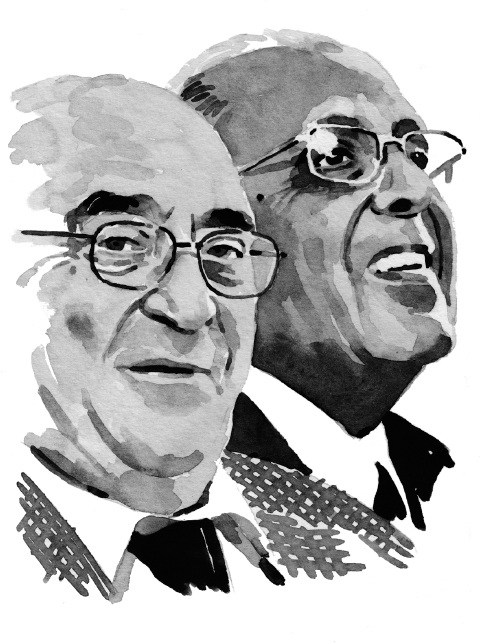

AHMED ‘KATHY’ KATHRADA AND DENIS GOLDBERG, FREEDOM FIGHTERS

I ENTER THE MAYFAIR HOTEL ROOM to interview Ahmed ‘Kathy’ Kathrada and Denis Goldberg, two of Nelson Mandela’s fellow freedom fighters, who stood trial and were imprisoned with him for nearly three decades of hard labour. The first thing that is pointed out to me is the modestly sized bed.

‘That bed is bigger than the cells we were kept in on Robben Island for twenty-seven years.’

In a small, simple way it brings to mind some of the deprivations these men endured in dedicating their lives to fighting apartheid in South Africa.

Between them they have experienced the worst of what humans do to one another – torture, violence, the murdering of loved ones, unjust imprisonment, solitary confinement, thirty years of separation from their families (Denis’s wife was allowed to visit twice in the whole period of his imprisonment).

Despite these experiences, not once did they withdraw from the fight. They made a pledge as young men to overthrow apartheid and they spent every waking hour of the next sixty years doing so.

So where did this commitment to cause, this resilience to hardship come from?

Kathy can pinpoint the moment. It was aged twenty-two, on a visit to Auschwitz as a young man after the end of the Second World War. Here, among the profoundly disturbing reality of what had happened (evidenced by the human bones still scattered casually around the ground), that a dark truth dawned upon him. ‘Stood there, I realised that the logical conclusion of racism was genocide. It became clear to me we had to end apartheid to prevent the same happening to the South African people.’ After seeing what he saw, and having reached the conclusion he did, it meant he had to take up and never give up the fight.

An understanding of the history of man’s struggle for freedom also helped to form their resolve. Denis recounts that as a young white man he was raised by socially aware parents who not only made sure he respected all people who came to their house irrespective of colour, but also educated him about the Gandhi-led movement for Indian independence, told tales of the lesser-known German resistance and explained the hundred years of struggle by indigenous South Africans against British colonisation. These stories of resistance against an oppressor inspired him and showed him that freedom was not only worth fighting for, it could also ultimately be won.

They are two of the most remarkable men imaginable. As they recount without any bitterness the extreme costs of their sixty-year fight, the humour remains constant (How did you manage to cope with the hardship of prison? ‘We got lots of practice.’) and their energy and fight is undimmed.

The morning before we met, Denis had been invited to 10 Downing Street to meet David Cameron. Denis’s opening salvo to the Prime Minister: ‘So when are you bloody Imperial Brits going to stop beating up on South Africa?’

Denis is the more fiery of the two gentlemen. In some ways his story is even more pronounced, as he was a white man fighting for an end to apartheid, which was virtually unheard of and meant he was shunned by his own community in a way the other fighters were not. But all men paid the same price for fighting for freedom: life imprisonment.

In fact, even worse had been expected. During the infamous Rivonia court case (1963–64), where Denis, Kathy, Nelson Mandela, Andrew Mlangeni and others stood trial for their action against the South African apartheid regime, everyone expected them to receive the death penalty. They had signed up to their campaign from the beginning knowing it was the most likely outcome.

Following a three-hour speech by Nelson Mandela, the final verdict shocked everyone: life imprisonment. When Denis’s mother, who was hard of hearing, called from the gallery, ‘What is it? What’s the verdict?’ Denis replied, ‘It’s life. Life is wonderful!’, a response which gives a sense of the undying resilience and granite-hewn optimism of the men.

An uncomfortable lump in my throat forms as I consider that this moment of relief was then followed by more than twenty years in prison, experiencing the hardest of incarcerations. Understandably, they prefer to dwell on the outcome, not the experience, the victory, not the battle.

So I ask them about how they achieved the success. What brought about the end of apartheid? With totally clarity, the men cite four factors: the armed struggle, which meant the government undermined itself by increasingly spending more and more money on fighting its own people; themselves as political prisoners, which gave the movement respected figureheads unjustly treated; the international solidarity movement, where governments and civil organisations boycotted South Africa and signalled their opposition to the regime; and finally, the people’s struggle in South Africa – the United Democratic Front, the trade unions, civic organisations – the majority of the country coming together to protest, to disrupt, to say No More.

Kathy is clear that, of the four aspects, the mass struggle was the most important. As Nelson Mandela said to the Minister of Justice from his prison cell in Robben Island, ‘The future of South Africa can be by bloodshed and in the end the majority will win, or it can be by a negotiated settlement.’ With the majority of the people actively protesting and pushing for change, the government eventually conceded.

When I ask what has been the main lesson from their most remarkable of lives, the answers are the most profound of all I have heard.

From Denis:

‘I am going to quote John Stuart Mills from the mouth of Nelson Mandela, “To be free it is not sufficient to cast off your chains, you must so live that you respect and enhance the freedom of others.” It’s the same concept of what Archbishop Desmond Tutu calls Ubuntu. I am who I am only through others in society. We’re humans in the end, and that’s what it’s all about.’

And then Kathy quietly, gently but definitively states his truth:

‘And ultimately, the fight for justice will inevitably lead to success. No matter what the sacrifices are.’

As these men know.

LILY EBERT, AUSCHWITZ SURVIVOR

‘WE WEREN’T SEEN AS ENEMIES, we weren’t seen as humans, to the Nazis we were just cockroaches. They completely industrialised their killing of us.’

I’m sitting talking with Lily Ebert in a quiet room in North London’s Holocaust Survivors Centre, the first of its kind in the world. Lily is a proud, defiant, eloquent lady, but as she recounts her experience of Auschwitz she pauses many times. Seventy years on, the pain of mankind’s most horrific genocide remains acute. As Lily says, ‘It is very difficult to explain something that is unexplainable.’

‘The lucky ones died’ is her reflection on the transportation to Auschwitz: hundreds of people rammed into railway cattle trucks in the heat of the summer, with no food or water for five days, surrounded by the dead bodies of those who didn’t make it. Lily recounts the last thing her mother did before the train arrived. She made Lily swap shoes with her. Hidden within the heel was a small piece of gold, the last of their family’s possessions. Call it a mother’s intuition, but when they arrived at Auschwitz, Dr Mengele, the Angel of Death, separated the masses into two groups: half were sent left to what would be their immediate death in the gas chambers, and the others were sent right to the slow death of starvation in the camp. Lily’s last memory of her mother, younger brother and sister is of seeing them being pushed left.

Inside the camp, Lily and her two younger sisters were stripped of their clothes and dressed in rags, fed on one piece of bread a day and housed in sheds crammed with ten times the number of people they were built for. Every day there were constant ‘selections’, where anyone deemed not fit enough to work was sent off to the crematorium next door.

Lily says the worst thing of all was the terrible smell emitted from that factory-like building, with the chimney that smoked twenty-four hours a day. It was only when she asked some fellow campmates what was made there that people explained that it wasn’t a factory, it was where they burnt Jews, and the only way out of Auschwitz was up that chimney. ‘We told them they were mad, that we didn’t believe them. But very quickly we found out it was true.’

In the hell of this experience, Lily promised herself that if she did somehow manage to survive she would spend the rest of her life telling people about Auschwitz so it couldn’t happen again. A promise she is keeping for the thousandth time by telling me her story today. That sense of purpose and the responsibility she felt to look after her two younger sisters gave her reason to stay alive in a place where she would otherwise rather have been dead.

It also gives context to one of the pieces of advice she wants to pass on: ‘To always have hope against hope. I was as down as a human being can go but look at me, I survived. I have gone from nearly starving to death to, seventy years later, being sent to meet the Queen and being given a BEM. So no matter how bad the situation, try to do what you can and don’t give up.’

However, her most precious piece of advice is:

‘Make always the best from what you have, no matter how little it is.’

She brings the thought alive by referring back to that one piece of bread they each had to survive on each day. ‘Some in the camp could not make the best of it, they ate it in a second and they dreamed to have something else, but there was nothing else, and they were the ones that didn’t survive. I would always eat the one piece of bread as slowly as possible and keep some for the morning hidden under my arm. And that helped me survive.’

At the end of our meeting, Lily proudly shows me a small gold pendant round her neck, which she has worn every day since being freed. She explains it is the piece of gold that her mother hid in her shoe, which she managed to keep hidden throughout her whole time in Auschwitz.

I reflect on what this piece of gold and its owner have seen and had to endure. The starvation, the brutal conditions, the worst of mankind. But it also creates a small question in my mind: given that she lost her shoes in the camp, how did she manage to keep the piece of gold? Eyes sparkling with triumph, Lily says: ‘I told you, you have to make the best of whatever you have. The only thing I had was that piece of bread, so I hid the gold every night in that and they never spotted it. I was cleverer than them.’

Lily Ebert: pure gold.

‘MAKE ALWAYS THE BEST FROM WHAT YOU HAVE, NO MATTER HOW LITTLE IT IS … I WOULD ALWAYS EAT THE ONE PIECE OF BREAD AS SLOWLY AS POSSIBLE AND KEEP SOME FOR THE MORNING HIDDEN UNDER MY ARM. AND THAT HELPED ME SURVIVE.’

– Lily Ebert

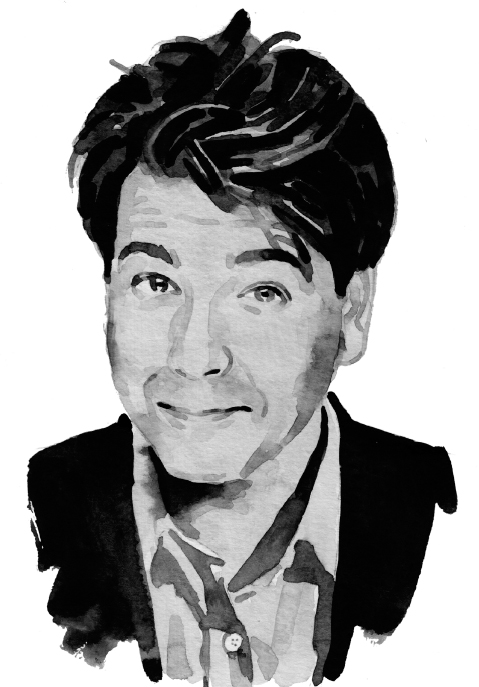

THE HEART-BREAKING GENIUS OF RICHARD CURTIS

IF THE OSCARS HAD a category for Best Human, Richard Curtis would get nominated. Not for the pleasure his script-writing has brought to the masses, abundant though that is, with Four Weddings and a Funeral, Notting Hill, Love, Actually and other such treasures to his name, but for his decades-long commitment as co-founder, leader and/or chief agitator for such era-defining social initiatives as Comic Relief, Red Nose Day, Make Poverty History and Live 8. No other person has done more to make development aid and charity part of the mainstream.

From such an evolved human being, I have high hopes for his best piece of advice, especially when he says he’s thought about it in advance and committed his wisdom to paper. ‘So here it is,’ he says, as he opens his writerly, leather-bound notebook. He sits forward, clears his throat and announces:

‘Don’t let your mum cut your hair. That’s important.’

Closes book, sits back.

He’s serious, sort of. ‘My mum did mine once and I didn’t talk to her for three weeks.’ This recollection triggers a follow-up insight. ‘And if you’re a mum, don’t cut your son’s hair, he’ll hate you.’

It’s not just his wisdom on hairdos that is rooted in childhood, most key attributes of his life have an invisible string that, when pulled, brings up a story from his younger years. He confesses to having scripted so many romantic movies ‘because I had my heart broken at university’, and he writes a ‘Hapless Bernard’ into every movie, an in joke-revenge of a man who once stole his girlfriend.

More significantly, it was during one of his younger, love-struck, feeling-sorry-for-himself moments that his father said something that changed Richard’s perspective on life in general. ‘My dad, not unkindly, described his own life at eighteen, which was finding himself fatherless and cleaning toilets on a ship to earn money, and compared it to what my life was like. And I was absolutely fixed after that. It gave me a sense of perspective between my problems and other people’s that I have kept forever.’

A second slice of childhood wisdom from his dad has also reverberated through his life: ‘He always said you can’t be happier than happy.’ The idea that if you are content and things are good, do not be disturbed by the possibility that they could be better. ‘Don’t let a lovely day out in the countryside be ruined by the fact that it’s not sunny.’

As with his movies, though, there is a twist. ‘I say that, but I am an unhappy person almost all the time.’ I assume he’s joking, but in response to my protestations he explains that raising money for the development of the world’s poorest nations means he gets his heart re-broken several times a day.

‘With the charity work I feel the pressure of every phone call, that if I can talk this person into doing something, kids survive, if I don’t, they won’t. Just today I got a call from a lovely guy saying he won’t be able to do a sketch and of course I have to lie and say “It’s OK, you helped last year,” but inside I am dying.’

So his best piece of advice comes directly from his experience of trying to change the world, but also reflects the frustration and heartbreak that comes from knowing people talk a good game but often fail to help when the need for aid is so vast.

‘None of us should ever underestimate our ability to change people’s lives. There is a direct cause and effect of what we do here and what happens there. But if you want to help you have to actually do something. You can’t just talk about it. My motto is “If you want to make things happen, you have to make things.” Create an object, a slogan, a film, a little book, a badge, a hashtag, a Red Nose Day … make something so wonderful that it captures people’s hearts and minds so they can’t help but be dragged in and help. And even better, make it funny too. That’s all I have ever done.’

And there is no one who does it better.

FOR SOMEONE RUNNING ONE OF the world’s largest and most complex cultural institutions, Jude Kelly, artistic director of the UK’s Southbank Centre, has a simple description of what she does. ‘I tell stories. That’s what I have been doing all my life.’

It is a statement she means literally. Throughout her career she has directed more than a hundred plays, including for the Royal Shakespeare Company and in the West End, and now has the biggest job in the arts in the UK, but it all started with her as a young girl putting on plays in her back garden, using the neighbours’ children as cast members and their parents as an audience.

Those childhood plays not only gave clarity on what to do with her life (at the age of eleven she declared she was going to be a theatre director and has been making it happen ever since), but those early exploits also provided the defining attribute of her approach to story-telling: the absolute imperative of making the arts fully inclusive. ‘I loved the idea that the whole neighbourhood would gather together to watch the plays, and I felt very upset if everyone wasn’t there. I hate people being left out. Not just for their sake, but for our sake too.’

It is an organising principle that has driven Jude ever since: that both the community and the art of that community are better served when everyone is included. ‘We need people with different life experiences so we can hear each other’s stories, to add to them, to understand them, to disagree with them, to help people stop feeling self-conscious about bumping into other tribes and help people feel there could be something richer if they experiment with other human relationships.’ In short, making the arts inclusive deepens society’s empathy and cohesion.

The Southbank Centre is publicly funded, which furthers her resolve to make all welcome: ‘The whole of society pays into the pot, so everybody needs to get a slice: that is my absolute driving energy and belief system.’ And she delivers. On the day I visit the Southbank there is a Pram Jam for parents with young children, an Indian performance artist, a classical concert by refugee musicians, a banging techno night, Jeremy Irons reciting Shakespeare, an a capella beat-boxing show, a circus, some stand-up comedy and a street-food market. Something, in other words, for everyone.

Jude also has a parallel role as founder and leader of Women of the World, a global festival that celebrates women and girls and looks at the obstacles they face. It fits with her mission of getting everyone included, with a clear focus, in this case, on gender equality. She says her awareness of the ever-present issue has been heightened by being a female leader and the sheer number of times young women have come to ‘ask for advice on the things they were struggling with: work/life balance, whether to have children, what would happen to them if they did, the way they were treated at work, the way they were treated by partners, issues of violence, rape, online porn, body image, it goes on and on, but also positive stories too, things women and girls have achieved’. So she decided to start the festival as a place for people to come together, talk about their issues, feel positive and explore what gender equality could one day look like.

Amazingly, she originally received some resistance to the idea. ‘When I started the festival people said “Really? Haven’t we already done gender equality?” But I knew we hadn’t done it by any means. And that was before Malala was shot, before Boko Haram had captured the Nigerian girls, before the Delhi gang rapes, so we need to pick up the stone and look under it. But also celebrate the things that have been achieved, the wonderful stories too, so it gives us stamina and energy.’

Jude says the issue has to be tackled in the arts, too. ‘Most plays, most films, most novels, most artworks historically have been by men, and there’s always been a central doubt expressed over and over again, can women be truly creative compared to men? Historically there has been a view that says, well, women have children, that’s their creativity. It’s a version of the same thinking that says black people have strong bodies but they’re not very intelligent, or the Chinese are very clever but don’t have an emotional life, all these damaging stereotypes framing half the human race inside a patriarchal power structure that has been inherited and internalised over thousands of years.’

This mission to tackle and defeat the ingrained issue of gender equality is much more than a day job. It strikes me as the story she will most want told about her life, and in keeping with such a script she offers her most valuable piece of advice about, and to, women:

‘WOMEN HAVE TO HONOUR THEIR OWN POTENTIAL. WOMEN MUST GIVE THEMSELVES THE RIGHT TO THRIVE IN EVERY SINGLE WAY, AND NOT DEFINE HOW LOVING OR HUMBLE THEY ARE BY THE AMOUNT THAT THEY ARE PREPARED TO STEP SIDEWAYS TO ACCOMMODATE SOMEONE ELSE. THEY NEED TO SAY, “I’VE GOT ONE LIFE, I’VE BEEN GIVEN LIFE, IT HAS BEEN BREATHED INTO ME AND HERE I AM AND I SHOULD USE IT FOR THE BEST POSSIBLE PURPOSE.” WHATEVER EACH WOMAN HERSELF DEFINES THAT TO BE.’

– Jude Kelly

I’M ON THE PHONE TRYING to arrange a meeting with Michael McIntyre, the highest-grossing comedian in the world, but I can’t: he’s making me laugh too much. The experience, however, is at least answering a question I’ve always asked myself: are professional comedians funny when they’re not on stage? In this case, the answer is: oh yes.

When we finally do meet in person, it continues. Michael starts by noting that I’m talking too loudly for a restaurant – almost as noisily as an American, he adds in a faux-bitchy whisper. He confesses to suffering from what he calls ‘restaurant hush’, the British middle class need to speak quietly when you are somewhere a bit posh.

Surprisingly, for a chat with one of the world’s funniest men, we quickly get into the topic of financial planning: the importance of never spending more than you earn, of avoiding the perils of credit cards and compounding interest. The reason: as a struggling stand-up he spent ten painful years spiralling into debt before making it big. ‘By the time I was thirty my career had gone nowhere and I’d got myself £40,000 in the hole. I was sitting in my room and thought, my life is not my life, I’m renting everything: the flat’s rented, the furniture’s on credit, the TV I’m paying off at Dixons … even that video needs to go back to Blockbusters.’

It’s funny material now but was serious back then. The bailiffs were called in. The first time they took his car, then the furniture, then his appliances. On one visit he realised there was a man with a boom microphone accompanying the debt collector. When Michael queried the recording equipment, he explained he was making a documentary about bailiffs for Radio 4. ‘I said, “I can’t be in that,” but then I thought maybe this could be the break I’m looking for, so I started to try and be funny, thinking maybe if I’m on the radio someone will get in touch.’

So what took him from those dire straits to centre stage? A simple but fundamental thing happened: he had Lucas, his first child. According to Michael, comedians get funnier when they become parents, mainly because they have to. For him the effect was instant: the sense of responsibility, the need to provide. ‘I thought I’m going to do whatever it takes to make it before he can speak. I don’t want his first words to be, “Daddy, why is that man taking the video recorder?”’

So the motivation was clear, but how does a comedian actually make themselves funnier?

‘I was crazed with it. I started doing gigs seven nights a week, for less money, for no money, just to keep practising, to get the jokes together, and to get the stage time. I knew if I could get one big laugh, then if I worked hard enough I’d get another and then another.’

Over time he built a twenty-minute set he considered bullet-proof (‘I could make twelve people in a room above a pub who weren’t really listening start to cry with laughter’), then he rang up the biggest agent in comedy, got him down to a gig in a small club, and gave the best and most important performance of his life.

When he came off the stage, the agent simply said, ‘You’re a revelation,’ and booked him for his first TV gig on the Royal Variety Performance. And then, boom. Like most overnight successes, it had taken ten years for him to get there.

Getting the stage time, never mind screen time, is somewhat easier now for Michael, as the country’s most in-demand comedian. But he still works the small gig circuit, doing dingy clubs on rainy Tuesday nights whenever he’s crafting new material. And he still remembers how painful it can be when you don’t have the money, when things aren’t working, when the situation is looking pretty hopeless. So he passes on this advice to those at that stage:

‘You somehow need to find a way to believe, to keep going. But it’s not enough to just say to yourself “be confident”, you can’t just BE confident, you have to surround yourself with people who bring the best from you, who will help you, who will help you grow that confidence. I’m like Britain’s Got Talent. I need my three yeses. I need my wife, my mother and my agent to all say, “Yes, that was good.” Then it’s like, all right, that works, I can keep going. I put my success down to that: my wife, my family, my support network. My three yeses.’

This time, he’s not joking.

NOELLA COURSARIS MUSUNKA, MODEL CITIZEN

THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE Congo is a contradiction rendered as a country. It has more natural resources than any other nation in the world, but is one of the poorest in GDP and life expectancy. It has enough latent hydro-power to fuel most of Africa, but less than 10 per cent of homes have electricity. It has an image in the West of a barren, war-stricken land of heinous crimes, but is one of the most verdant and beautiful countries you could ever hope to visit, with people as friendly and welcoming as any on earth, a fact I can attest to, not just from having spent time there but also because I am sitting opposite one of the DRC’s favourite daughters.

The lady in question is Noella Coursaris Musunka, the international model who splits her time between fashion shoots for Vogue and Agent Provocateur and a parallel life running Malaika, an organisation she founded, providing education and schooling to young girls in the DRC.

Noella’s backstory is that of a woman who has known tough times. She was born to a desperately poor family in the Congo and lost her father at the age of five. In a country where seven million kids don’t go to school and where life expectancy is just forty-eight, her mother took the understandable decision to send her to be raised by her aunt in Europe. But Noella never forgot her childhood and her home, and has used the currency of her modelling career to become one of the brightest lights and biggest advocates for her country of birth.

She was motivated to combine her career in fashion with tackling education in the DRC for defiantly positive reasons. ‘I’m a spokesperson for the beliefs that I want for my country. I want children to be taught that they are living in an amazing country, an amazing continent – that we have nothing to envy in any way.’ At the sharper end, she also wants the people of the Congo to benefit more from the resources of their country. ‘If you get on a plane in the Congo, it’s full of Americans, English, Chinese and Indians, but very few Africans, it’s mad. It seems a lot of people love our resources!’ she says laughing, but meaning it.

Ultimately Noella wants to help end the era where Africa is treated as ‘less than’ the rest of the world and, to do so, education is the answer. ‘Through quality education our own people can become agents of change, become leaders of their own country, so we can work with the West as equals, that is what’s missing.’

She makes no boast about the scale of her work. At the end of the day, she is educating just thousands of children in a country that is failing millions, but it is a start. And she uses her voice and the platform of her career to agitate others to do the same. This mission of encouraging others to act, to get involved, to do something rather than nothing, is inherent in her advice.

‘ANY VOICE YOU HAVE IN THIS WORLD, YOU HAVE TO USE IT. WHATEVER MONEY YOU HAVE THE DAY YOU DIE, YOU DIE WITHOUT IT, SO DONATE IT. IF YOU CAN ONLY GIVE AN HOUR OF YOUR TIME, THEN DO THAT.’

– Noella Coursaris Musunka

WHAT DO YOU DO WHEN ‘the Most Powerful Woman in the World’, as ranked by Forbes Magazine, invites you to dinner? You say yes, of course. The woman in question was Indra Nooyi, the Global CEO of PepsiCo and board member of the Federal Reserve. The context was that Innocent, the juice business started by myself and two friends, had been growing fast and, unknown to us, had got us on the radar of some of the major food and drinks companies. Indra’s people called us out of the blue and said she would like to meet. They suggested dinner next time she was in London.

It seemed churlish to say no, and I was curious about what it took to be a global CEO of a business responsible for operations across the planet, with hundreds of thousands of employees, creating opportunities and issues in every time zone. How did she manage the workload? What was life like? Did she have any good advice? The dinner proved illuminating on all three fronts.

We started the evening with polite chit-chat, questions like ‘So how long are you in London for?’ and other such conversational placeholders. Interestingly, it turned out Indra was leaving that evening, as soon as we finished dinner. Her private jet was fired up and ready to go and would be heading from London to New York after our coffees and mints. Meanwhile, her husband, another global CEO of a big tech company, had his private jet in New York also ready to go, destination London. They had two daughters and a rule that one parent should always be at home with them, and were timing flights so that when she took off, he would too. At around 1 a.m. that night, somewhere above the Atlantic, they would pass each other at a combined velocity of a thousand miles per hour, like proverbial (extremely fast) ships in the night. I found the image memorable. As I did the idea of a two-jet household.

When we got on to her approach to work, she spoke with total passion. She deeply loved what she did, and she did it a lot. At one point in the conversation, Indra asked, ‘You know that buzz you get when you haven’t been to sleep for three nights because you’ve been working on a deal?’ I had to admit to her I did not. In fact, I said, I didn’t even know what the buzz from staying up for just one night was like – well, not for work anyway – an answer that momentarily perplexed her.

She told me that she’d once done eight nights straight without going to bed, such was the size of the deal she was working on. I queried whether this was even physiologically possible, and she admitted, under my cross-examination, she had grabbed fifteen minutes on her office couch on the eighth night. To this day, I still don’t know if she was playing mind games on me. If she was, it worked. I thought that if that’s what it takes to be a global CEO, I’d better stay a local one.

She was brilliant company: charming, eloquent, engaging, but capable of saying the most unexpected things. When I got to asking her advice, she first wanted to dispense a few leadership tips, the most memorable of which was: ‘I get my board to come round to my house once a month and I print out song sheets and we all sing songs together. I really recommend you do the same.’ When I said I wanted her single most valuable piece of advice, this is what she offered.

‘Don’t take holidays. When you get to my age you will regret taking them. Give yourself a maximum of a day or a day and a half a year. And use that to read books on your industry. The rest of the time you should just work.’

The first thing I thought was, ‘Wow, that’s genuinely the worst piece of advice I’ve ever heard.’ The second thing I thought was, ‘You need to go on holiday more often.’ I was going to say just that, but then with my third thought I remembered that she was ‘the Most Powerful Woman in the World’, so I just kept quiet, nodded and ate my pudding.

‘DON’T TAKE HOLIDAYS. WHEN YOU GET TO MY AGE YOU WILL REGRET TAKING THEM. GIVE YOURSELF A MAXIMUM OF A DAY OR A DAY AND A HALF A YEAR. AND USE THAT TO READ BOOKS ON YOUR INDUSTRY. THE REST OF THE TIME YOU SHOULD JUST WORK.’

– Indra Nooyi

THE NORTH FACE OF the Eiger is the most infamous climb in the world. It’s known in the mountaineering community as ‘The Wall of Death’, a mile-high, concave cliff-face covered with ice, loose rocks and tragedy: as difficult and as unforgiving to climb as it sounds and looks.

The first two people ever to attempt climbing it died trying. And so did the next four, starting a death tally that currently stands at sixty-five. When a group did eventually summit the North Face, it took them more than three days. I give this historical context because Ueli Steck, the Swiss climber I’m currently with, recently did it in under three hours, an unimaginable speed made possible only by his gravity- (and sanity-) defying decision to do it without ropes. It was an achievement so disproportionate, so unprecedented in the annals of mountaineering, that it didn’t just rewrite the rules of climbing, it seemed also to rewrite the laws of physics.

As an amateur climber myself (and I strongly emphasise the word ‘amateur’) I tell him I struggle with his decision to climb without ropes, which are the only hope you have of remaining safe if you make a mistake and fall (which, in my experience, happens often).

‘I remember when I started climbing and I heard there were people climbing without ropes I thought to myself that’s insane, I will never do that. But it’s a process, figuring out stuff, doing it better, and that’s what drives me.’

But what about the chance element you can’t control? ‘You just have to accept it, you have to commit.’ And the fear? ‘When I’m climbing, there is no fear. If you feel fear, it’s because you’re not well prepared.’

As advice goes, it sounds potentially like bravado, but in Ueli’s case it’s not. In fact, in Ueli’s view having bravado is deadly: you need an absence of ego to stay safe. ‘You have to make sure you feel no pressure to get to the top otherwise you start making the wrong decisions. On a climbing day, I always say “I’ll just go and have a look.” I never say, “I am going to do it.” And if I have a bad feeling, I just come back down. I believe if you stick to that then you never make a mistake.’

Of course, with Ueli’s approach to climbing there literally can never be a mistake, not one.

‘I really play on the edge. The time on the Eiger, I had to move fast, so I allow myself to hit only once with the ice axe, no compromise, never twice. Full commitment each time I place the axe. And it works, you really concentrate, you really hit precise.’

It’s a way of thinking that turns inside out what other human beings would do: if you were a mile up a vertical cliff-face and your life depended on the ice axe you’re about to put all your weight on, you’d want to check it would hold. Ueli instead uses the consequences of what it would mean if it won’t, to make sure he concentrates hard enough to place it correctly in the first place. That is some advanced-level psychology.

On a deeper level, that degree of commitment is perhaps partly enabled by his personal take on the potential consequence. ‘If I fuck up, it’s over. I’m dead and I don’t have to live with my mistake.’ Amazingly, he says he would rather have that outcome than, say, the pressure of being a CEO, ‘where if you screw up, you have to fire people and they lose their jobs and you know it was your fault and you have to live with that your whole lifetime. I don’t know if I could handle that.’

It’s a final comment that reinforces the huge gap between myself and Ueli. I have actually climbed the Eiger – it took me two days and was by the incomparably easier Western ridge, and involved a lot of ropes and guides, and there were still plenty of moments when, clinging trembling to the rock, I would have happily fired my own grandmother to get off that damn mountain.

But I decide not to mention that to Ueli.

LOOKING BACK, I HAD AN itch of apprehension before making the call. I was due to interview Margaret Atwood, the Canadian-born, internationally renowned Booker Prize-winning novelist; a soothsayer and chronicler with the wisdom that comes from being over forty books old. To gen up, I read a couple of interviews online, but they thrOw up two uncomfortably pertinent facts: firstly, she hates choosing favourites of any kind, and secondly she doesn’t believe in giving advice. The reason for my call? To ask for her favourite piece of advice.

The phone call starts well enough. We talk of Pelee Island, a tiny gathering of land in Lake Erie, south-west of Toronto. She’s recently been hosting the annual ‘Spring Song’ there, a bird race and book-reading event that raises money for the Pelee Island Heritage Centre while drawing attention to the migratory birds that use the island to rest their weary wings. Margaret empathises with them: the island offers her respite too, and a place to write with few distractions: ‘The locals point tourists looking for our house ten kilometres in the wrong direction.’

But I know I can’t hide behind this island talk for long, so I outline my plans for the book, explaining that I am looking for her best piece of advice. Like all her answers, it comes quick and complete. ‘Oh, I never give advice unless I’m asked for it.’ But it’s a better response than I am expecting, so I point out that I am asking.

Unfortunately, it is not the key to the conversation I was hoping it might be. ‘OK, but what are you asking advice about? Advice needs to be specific. For all I know, you could be looking for advice on how to open a jar.’ I explain that I’m OK with overly protective lids (run under a hot tap or gently hit the side to loosen), I’m more looking for advice that she particularly holds to be true or useful in life generally. ‘Yes, but for who? For what? Advice always relates to the person and the situation. For a start, what if you suffer from depression? That can make a massive difference to how you are in life and what you might need or find helpful.’ Ah, I wasn’t expecting that. I know 25 per cent of people suffer from mental illness and I don’t want to imply a sentence or two of wisdom will somehow solve their issues. So I tell her I take her point, and say let’s assume we’re talking about the other 75 per cent. ‘OK. So are these people born to loving parents or not? That is another huge impact on our lives and I think my advice would differ depending on that factor.’ Hmm, now where? On the one hand I agree that a few words of advice are a poor substitute for not being loved as a child, but on the other hand, it’s going to bugger things up for me and my book if I can’t get a piece of advice out of Margaret Atwood.

I take some solace from her tone. She is not coming across as someone whose aim is to undermine, she actually seems engaged and keen to help. In fact, it appears she’ll happily do anything for me, with the exception of one thing. It’s just unfortunate that it happens to be the only thing I want of her.

I decide to call on God for help. ‘Look,’ I begin, ‘if you take religion, you can essentially boil its better teachings down into some human behaviours that are universally beneficial to all.’

‘Ah yes, love thy neighbour, forgive one another, that kind of thing?’

‘Yes, exactly,’ I enthusiastically reply, thinking now we’re getting somewhere. My optimism proves short-lived.

‘Trouble is, I’m more of a revenge kind of gal myself. But when someone smites me I’m normally too lazy to do anything about it. I tend to let karma take care of things.’

OK, so religion didn’t work. I try psychology. I give a simplistic overview of studies into human happiness, which show that people who help others end up feeling happier about themselves. Isn’t there something in that?

‘Sure, unless you do it too much, and then you end up exhausting yourself, and that doesn’t help anyone.’

I’m now starting to confront the uncomfortable truth that I am dealing with someone on the other end of the phone who is just plain smarter and of quicker wit than me. I’m basically in a verbal fencing match with one of the greatest writers alive, and, as you would expect, I am losing.

Margaret senses I’m on the ropes and decides to give me a breather. ‘Look,’ she explains, ‘I’m a novelist. In my world, everything is about the character. Who are they, where are they? Are they old or young, rich or poor? What do they want? Until I know what they are wrestling with, how can I give advice?’

‘President Clinton managed to,’ I protest.

Margaret’s interested. ‘Oh, and what did he say?’ I recount his advice of the importance of seeing everyone: the person who pours your coffee, the person who opens the door for you. I say it’s a piece of advice that strikes me as something relevant to all humans. ‘Unless they’re a writer trying to get a book finished, then I’d tell them the last thing you need is to see people more, you need to stay home and work.’

The conversation has the feel of a cat playing with a mouse. And I’m not the one purring. I resort to pleading: given all that you’ve learnt, there must be something you think is worth passing on.

‘OK, I’ve got something for you. How about this: “When it comes to cactii, it’s the small spikes that get you, not the big ones.’

‘Is that a metaphor for life?’ I ask hopefully.

‘No, no, I mean it literally, I was just in the garden doing the weeding before you called and those little devils are painful.’ I explain that it may be a little too specific for this book, but I’ll bear it in mind for a future volume on gardening tips.

I’m conscious I’m nearly out of time. I have one last go. Still wanting to help, Margaret asks me one more time to focus down the audience for this intended advice. I confess I haven’t narrowed my intended audience down any further than to my fellow Homo sapiens. Margaret lets out a short, sharp laugh. ‘But aren’t you then just talking about a book of trite sayings that you’d read in the toilet, full of things like, “Make a smiley face and you’ll feel more smiley”?’

‘Of course not,’ I reply.

But secretly I think to myself, maybe I can just use that.

‘I’M A NOVELIST. IN MY WORLD, EVERYTHING IS ABOUT THE CHARACTER. WHO ARE THEY, WHERE ARE THEY? ARE THEY OLD OR YOUNG, RICH OR POOR? WHAT DO THEY WANT? UNTIL I KNOW WHAT THEY ARE WRESTLING WITH, HOW CAN I GIVE ADVICE?’

– Margaret Atwood

THERE’S BEEN A SMALL CHANGE in wardrobe since I last met Tony Blair. Back then, he was in Office, and sporting classic PM-wear: smart suit, crisp shirt, party-loyal tie. Now, in his post-premiership world, things have loosened up a little: sports jacket, blue jeans, open-necked shirt. There’s also a pretty healthy suntan going on. Life after Office seems to be treating him well. Tony Blair is looking good.

The same can be said of his private offices too, tucked into a discreet corner of Grosvenor Square. They are beautifully and stylishly appointed, nicer in fact than the rooms in 10 Downing Street; a benefit that comes from being able to choose your building, rather than the building choosing you.

But while things around him may have changed, Tony Blair has not. His most distinctive quality remains undimmed: a catalysing energy that radiates from him. His enthusiasm, engagement and intellect imbues the room with an intangible sense of more-to-come, that things will only get better. Just being in Tony Blair’s presence encourages you to think bigger, to work harder, to do more.

In fact, according to Tony Blair, he’s actually working as hard as he ever has, wrestling with some of the world’s toughest sudokus – religious extremism, African development, peace in the Middle East. Whatever your views on Tony Blair, the man is committed. There’s not a lot of golf going on.

We talk of his time in Office. I say that it seems to me the quintessential experience of being a prime minister is on any given day you work under the most intense and unyielding pressure, and just when you think it can’t get any worse, a completely new issue broadsides you, one that you somehow also have to now deal with. And alongside all of this, your rivals in the House and the media are deliberately giving the very worst possible interpretation to your very best intentions. ‘Tell me about it,’ he says ruefully. ‘I could write a book on that one.’

Alongside this constant stress and pressure, he says that, as Prime Minister, you also feel ‘a sense of inner awe at the magnitude of the decisions you’re taking on a daily, even hourly, basis, which you’re aware affect the lives of people very deeply’.

So how does one cope with the relentlessness of it all? Tony lays out his four-point PM plan to keep on an even keel. Firstly, count your blessings. No matter the pressures, don’t forget it is an enormous privilege to be doing such a job. Secondly, remember, as his wife Cherie would repeatedly point out, it is voluntary, no one is forcing you to be Prime Minister. Thirdly, have a belief in what you are doing, and the people you are doing it for. And fourthly, don’t get too up yourself, you need to keep a sense of humour. Keep those four things at the front of your mind and the stress becomes more bearable.

He also advocates making space for what he calls ‘some personal hinterland’: spend time with the family; play the guitar, as he famously did; take holidays. Not that you’re ever fully off-duty as Prime Minister. Even on the family vacations, Tony Blair would travel with a small office and every day fulfil some PM responsibilities. In his ten years he never got a whole day off. He’d always be working, even if working on the suntan.

It begs the question: did he actually enjoy being PM? ‘Enjoy always struck me as a weird word to use about the job. I would say that I felt a great sense of purpose and passion about it. But enjoy in the sense of pure pleasure? Only at very rare moments, such as securing the Good Friday agreement and winning the Olympics. They felt good. But the main satisfaction came from moving forward on what we wanted to achieve in government, on the programme of reform we set out.’

This commitment to public service, to helping people, to improving things is clearly the internal engine that powered him through a decade in power. But he hadn’t always wanted to be a politician. In fact, it was only when his father-in-law took him into the House of Commons that he discovered this calling, his vocation. ‘Stood there in the House, I just got this sense of “This is where I need to be, this is what I need to be doing.” I was a lawyer at that time and quite a successful one, but it never gave me that feeling. But once I decided to become an MP, I started waking up with a great sense of purpose every day and it never left me.’

Which takes us to his very best piece of advice:

‘People tend not to be accidentally successful. If you see anyone very, very good at something, they tend to be very driven by what they do and they work really hard at it. So find the thing that makes you passionate and do that. And if you can find something you’re passionate about that also makes a difference to others, it will be a greatly fulfilling quality in your life. In the end, the things that give the most fulfilment are the things you do for others.’

‘FIND THE THING THAT MAKES YOU PASSIONATE AND DO THAT … IN THE END, THE THINGS THAT GIVE THE MOST FULFILMENT ARE THE THINGS YOU DO FOR OTHERS.’

– Tony Blair

I AM IN THE PLACE WHERE the ley lines of architecture and gastronomy meet: the kitchen of River Cafe co-founder and million-plus cook-book writer Ruthie Rogers, inside her majestic Chelsea home designed by architect husband Richard Rogers.

The open kitchen is the prominent feature of the temple-dimensioned main room, a gleaming stainless steel altar dispensing bread and wine and whatever’s in season to hungry, grateful mouths. After a few ‘grrr’s and hisses from behind the scenes, two expertly made, bitterly dark espressos appear, along with Ruthie herself, the warmth of each matching the other. If you want to find the spirit of hospitality manifested in a person, Ruthie is it.

The River Cafe is an ode to the Italian way of life, where food and la familia intertwine. Although Ruthie was born in America, her husband is from Florence and thirty years of holidays in the family’s home have infused Ruthie with the passion of Italian cooking. ‘I would walk into Richard’s aunt’s kitchen and find two sisters arguing over whether pappa pomodoro should have water in it or just the tomatoes, and I thought this is the kind of argument I like.’

Richard’s mother, Dada, was dedicated to sharing her secrets of how to cook, eat and live with Ruthie. ‘Even on her death bed she was still passing on tips. Her last words to me were “Ruthie, I want you to put more cream on your face and less herbs on your fish.”’

Inspired by this convergence of love, food and family, Ruthie and Rose started the River Cafe as ‘a restaurant where we could create the kind of food that we ate in people’s homes in Italy’.

While the River Cafe is now in its third decade and seats hundreds of people a day, it started in the smallest way possible. ‘The original space was tiny, only enough to do thirty or forty covers a day. Plus, the council only gave us a licence for lunchtimes Monday to Friday, no evenings, no weekends, and exclusively for the employees in the offices where the restaurant was sited. So we had to sneak customers in, pretending they worked there.’

However, their ambition was about quality, not size: the goal was to become the best Italian restaurant in London. And word spread quickly about the authenticity of the cooking, even though customers weren’t technically allowed to go. Paradoxically, the opening line of the River Cafe’s first-ever review (in the Evening Standard by Fay Maschler) was, ‘I’m going to tell you about a restaurant that you can’t go to.’ But, as Ruthie puts it, the restaurant grew as they grew with experience. Over time more space was acquired, planning permissions were gradually improved and it evolved into the big, beautiful restaurant it is today. And that experience is why she advises that if you are going to open a restaurant or business ‘start small, think big, grow with control’.

Part of the enduring success of the restaurant is seeing the team as important an ingredient as any of the seasonally sourced ones coming into the kitchen. ‘People often talk to me about how much they love the food, but they always start by saying how good the people were.’ Her advice here is:

‘Give and you get back what you give. Treat everyone as individuals: understand how people are and encourage them. There is real discipline too underpinning the work they do. I strongly believe that you achieve more in a work environment with hope rather than fear … the whole concept of people shouting or bullying or intimidating is foreign to me.’

This River Cafe family is unusual not just for its closeness but also because, in an industry dominated by men, it was headed by two matriarchs, the second being Ruthie’s partner and fellow chef Rose Gray. ‘Our relationship was remarkable. We cooked together, worked together, wrote together, went to Italy together, we even wore the same clothes.’ The symbiotic nature of their partnership made Rose’s death in 2010 all the more painful, and daunting to deal with. ‘Rose was a force. When she died it was like becoming a single parent, but with eighty-five children. But I thought the greatest tribute would be to make the reataurant better and better.’

One year later Ruthie lost her twenty-six-year-old son, who died suddenly of a seizure in Italy. Ruthie likens this to ‘a tsunami. One minute you are safe on the beach looking out to sea, and then it strikes and you are drowning.’ I ask, if there is any advice she can pass on to someone being hit by such a tsunami of their own. Her answer reflects just how terrible an experience it is.

‘As much as I would like to, I don’t think I can, because people were giving me advice and none of it worked. The only thing that got me through it was the love for my children, the closeness and tightness of our family. I would be somewhere and one of my children would appear. I’d come down in the morning and a friend would be on the sofa. They would just somehow happen to be there for Richard and me.’ A beautiful tribute to the power and strength of her close friends and family.

Ruthie sticks with the water analogy and says that five years on ‘the waters are still rough, but you learn how to navigate, you learn what you can do, what you can’t do, the times you need to be prepared for’. And while it would be misunderstanding the depth of the emotions to say her work provided consolation, it did sometimes help bring distraction. ‘I found it too difficult to cook, it was too contemplative, I would stand there stirring the risotto and cry. The nights were better as they were busier.’

And the love and sense of family she had always shown to her team, the insistence she and Rose always had of treating people kindly, respecting them, encouraging them, meant at least she was in an environment that felt safe. ‘Obviously nothing is more important than your family, your children, the people you love, but I think that there’s an intertwining of work and family with the River Cafe and when I walk in I just think how great they are.’

She pauses for a moment, reflecting on what role the River Cafe has played in her life. ‘People say to me, “Gosh, you’re still here,” and I think to myself, “Well, where else would I want to be?”’

Which, to me, sounds like the ultimate measure of success.

‘Put more cream and less herbs on your face on your fish.’

– DADA ROGERS, VIA RUTHIE ROGERS

OUTSIDE SPORT, IT’S HARD TO claim that someone is genuinely number one in their respective field. How can you judge who is the best artist, writer, actor or whatever in the world? Jony Ive, the head of design at Apple Inc. and the most successful industrial designer of the modern age, is an exception to this dilemma. He is the man who crafted that convergence of artistry and technology currently residing in your pocket, and who worked with the world’s most famous and revered founder to create literally the most valuable company in existence.

For a man who genuinely is the ‘Big I Am’, he does not act like it. I meet him at a burger van eating some chips. Admittedly, it’s a burger van at a private party, and they are very nice chips, but with his extraordinary success also comes a high degree of humility and self-deprecation. It seems to be a trait among genuinely successful and credible people: they tend to be, for want of a better description, nice. He even offered me some of his chips.

I decline on the food, but ask for his number-one piece of advice instead. It was neither original nor complicated, but it is probably the single-most important driver of success – and certainly fits with the laser-like focus of his company:

‘You have to really focus. Just do one thing. And aim to become best in the world at it.’

He admits that wasn’t necessarily how he used to think. With a brain as creative as Jony’s, there are a thousand different things he would want to do. ‘I learnt the importance of focus from Steve [Jobs]. His view was you have to say “No” a lot more often than you say “Yes”. In fact, he used to ask me each day what I had said “No” to, to check I was stopping things and saying “No” to things and not getting distracted.’

My favourite thing about this story is that when Jony told it to me he paused and then confessed that he used to make up projects that he could then tell Steve he had stopped, so he always had an example of something he had said ‘No’ to when Steve came by. Which brings me on to a second thing about successful people, even the brilliant ones: like the rest of us, they are, at times, still faking it a little.

‘JUST DO ONE THING. AND AIM TO BECOME BEST IN THE WORLD AT IT.’

– Jony Ive

PARENTAL GUIDANCE WITH BARONESS HELENA KENNEDY QC

‘What people always say to me, even my mother, is “Why can’t you have some nice clients?”’ recounts Helena Kennedy QC, one of the UK’s most active and outspoken advocates of civil liberties and human rights. Admittedly, one can understand where that question comes from: her client list is chilli-peppered with the most controversial people in modern British history: the child murderer Myra Hindley, the IRA bombers behind the Brighton Hotel attack that aimed to kill Margaret Thatcher, and the ‘Liquid Bomb’ terrorists who we have to thank for not being able to take more than 100ml of fluids onto flights any more.