Chile Today

Modern Chile has gone through some seismic shifts, and we don’t mean an earthquake. Change, ranging from lifestyle to globalization, arrives at record speed in the country with the highest household income in Latin America. At the end of 2017, billionaire and former President Sebastián Piñera was elected for the second time to the country’s highest office, with promises to bootstrap the economy by modernizing infrastructure and slashing taxes for businesses. By banking right, Chile also has stepped in line with the latest regional trend.

Best on Film

Gloria (2013) A fresh and funny portrait of an unconventional 58-year-old woman.

The Maid (2009) A maid questions her lifelong loyalty.

Violeta Went to Heaven (2012) Biopic of rebel songstress Violeta Parra.

The Motorcycle Diaries (2004) The road trip that made a revolutionary.

No (2013) Did an ad campaign really take down a dictator?

180° South (2010) Follows a traveler exploring untainted territory.

Neruda (2016) The communist poet goes on the run.

A Fantastic Woman (2017) Transgender identity and society.

Best in Print

Deep Down Dark (Héctor Tobar; 2014) The gripping story of the 33 trapped miners.

In Patagonia (Bruce Chatwin; 1977) Iconic work on Patagonian ethos.

Patagonia Express (Luis Sepúlveda; 1995) Funny end-of-the-world tales.

Ways of Going Home (Alejandro Zambra; 2011) Meta fiction about a childhood during the dictatorship.

Chilenismos: A Dictionary and Phrasebook for Chilean Spanish (Daniel Joelson; 2005) Translates local lingo.

Mind the Gap

The highest building on the continent, the 64-story Gran Torre pierces the Santiago skyline as an irrefutable symbol of the country’s growing eminence. And yet, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Chile (along with Mexico and the US) has the highest rate of inequality among developed countries. One percent of the population holds half the country’s wealth. While education and tax reform progressed under the last administration, work remains to be done. Inequality has dogged Piñera since the first term of his presidency; now he’s betting that a business-friendly Chile is the solution.

The Changing Face of Chile

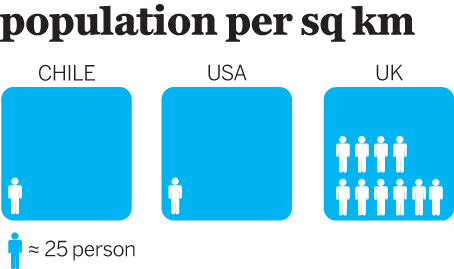

Drive the furthest reaches of Chile to the back roads of Patagonia and chances are that you will encounter a Haitian shop clerk and a Venezuelan running the popular roadside cafe. Far from the cosmopolitan capital, the country is undergoing a sea change. In the span of a decade, Chile has gone from a country with little immigration to one taking on similar proportions as the UK, relative to its population. Chile’s half a million migrants add up to just 3% of its total. Yet, they do represent a cultural shift that makes some Chileans uneasy.

During the 2017 election campaign, nationalist sentiments were stoked on both sides. Both the right and left agree that Chile’s 1970s-era immigration laws are well out of date. President Bachelet has posited that newcomers can fill needed roles as the country’s aging population leaves the job market. Many of the country’s immigrants are fleeing poverty and economic collapse.

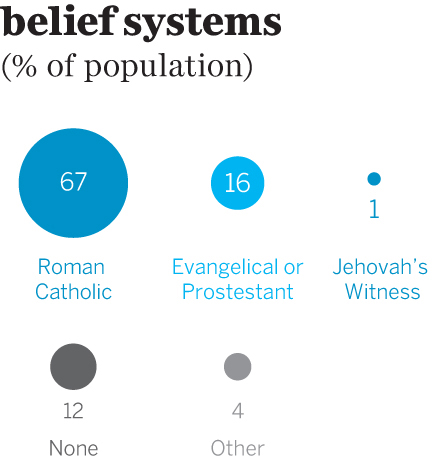

Social progress is on the national agenda. Chile legalized civil unions for both same sex and unmarried couples in January 2015. A bill recognizing transgender rights is in the works. Women have also taken to the streets to protest injustice, in areas ranging from femicide to abortion. Evolving from some of the most draconian abortion laws in the world, in 2017 Chile decriminalized abortion in cases of rape, fetal inviability and life-threatening pregnancies. While many would like to see women’s rights go further, it has not been easy to shake this Catholic country from its staunchly conservative mores.

The Future is Green

Worldwide tourism experts see Chile as a rising star, and it’s little wonder. Spanning diverse landscapes, the country with the driest desert in the world also has 80% of the glaciers on the continent. In 2017 alone, tourism grew by 17% and became 10% of GDP. The country held its first tourism summit and was designated the best adventure tourism destination by the World Travel Awards.

At the same time, Chile’s national parks are being supersized. On March 15, 2017, President Michelle Bachelet and American philanthropist Kristine Tompkins pledged to expand Chile’s national park system by 40,500 sq km, creating five new national parks and expanding three existing parks, amounting to an area larger than Switzerland. With this new designation, Patagonia will boast the highest concentration of parks in the world. The distinction translates to benefits for the local economy and the planet, not to mention the benefit it brings to travelers seeking out the most pristine corner of the world.

Yet conservation requires investment. In Costa Rica, the parks system spends US$16 per hectare for conservation, compared to Chile’s dollar per hectare; a difference that’s staggering. As interest in Chilean parks grows, so will the need for their funding.

Issues have already arisen. At Torres del Paine, Chile’s most popular park, stricter visitation regulations have been long in coming. Facing unsustainable levels of visitation, the park began to require reservations for overnight hikers in 2017. With stakes ranging from inadequate bathrooms to increased wildfire dangers, the casual informality of yesterday is no longer possible. There is no doubt that there is a sustainable future in investing in parks, but until it becomes a priority, all the fame in the world might not be of assistance.

POPULATION:

17.8 MILLION

GDP:

US$247 BILLION

INFLATION:

4%

INTERNET USERS:

12 MILLION

LIFE EXPECTANCY:

79 YEARS

MEDIAN AGE:

34

UNEMPLOYMENT:

6.5%