Chapter 4

Cultural Impact

Your girl catches you cheating…Fifty fucking girls? Goddamn…You try every trick in the book to keep her. You write her letters. You drive her to work. You quote Neruda. You compose a mass e-mail disowning all your sucias. You block their e-mails. You change your phone number. You stop drinking. You stop smoking. You claim you're a sex addict and start attending meetings.

Junot Díaz, 20121

It seems an axiom of modern sexual addiction that the ailment is both widespread and ever increasing. ‘Sexual compulsivity seems more prevalent now than ever’, warned the Handbook of Clinical Sexuality for Mental Health Professionals (2003). Even these rather restrained advisors were somewhat unrestrained in their estimates that up to 22 million Americans were addicted to sex in 1998 and that perhaps 40 million had ‘online sexual problems’ by the year 2000.2 The Sex Addiction Workbook (2003) said ‘Although we have no good data on the prevalence of such problems, they appear to be escalating at an alarming rate, possibly because of the impact of modern technology, in particular the Internet.’3 A 2008 article by a clinician in Psychiatric Clinics of North America, with the obligatory reference to Carnes and the rather negating use of the words ‘possibly’ and ‘may’, claimed that ‘Possibly 4 out of 10 adults in United States culture may be sexually compulsive.’4 One believer was blunter still: ‘Like it or not, sexual addiction is a rapidly growing problem, and predicted to be the next tsunami of mental health.’5

There is little doubt that much of the hype around sex addiction – either in endorsement or in denial – has been media-driven: ‘Duchovny in rehab for sex addiction’, ‘Are people becoming addicted to sex because of the financial crisis?’ and ‘Are you addicted to sex?’ were just some of the titles in the late 2000s.6 By the end of 2011 ‘The Sex Addiction Epidemic’ was the cover story in Newsweek, that gauge of the US cultural mainstream.7 The concept rapidly achieved a taken-for-granted status. The now deceased Cleveland kidnapper and rapist Ariel Castro allegedly blamed his crimes on sex addiction.8 And police officers have added sexual addiction as a coping mechanism for the trauma and stress associated with their work.9

One of the concerning aspects of this familiarization, and we will return to it later, has been the lack of critical inquiry in the reporting, even in quality publications like The New York Times, The Guardian and The Independent. Hence Joanna Moorhead's piece ‘Sex Addiction: The Truth About a Modern Phenomenon’ that seriously reported a psychotherapist's claims that 10 per cent of the sex addicts she surveyed were under 10 years old when their sex addiction started, and 40 per cent were under 16. This (retrospective) claim for ‘how young sex addiction starts’ was never questioned.10

If The New York Times can be used as a rough guide to educated popular usage, there has been an increasing familiarization with the concept of the sex addict since the early 1990s (Table 1).11

Table 1 References to ‘sex addict’, ‘sexual addiction’ and ‘sex addiction’ in The New York Times

| Years | No. of references |

|---|---|

| 1971–1980 | 1 |

| 1981–1990 | 11 |

| 1991–2000 | 87 |

| 2001–2009 | 129 |

It is worth pausing for a moment to consider the dynamics of the media's role in this habituation, where hardcopy combined with digital delivery and printed stories were reinforced by the moving image. Television, newspapers, magazines and the Internet converged in what became, in effect, the marketing of a concept. News blurred with entertainment in the form of reality TV, chat shows, celebrity culture, documentary and film, while the sex addiction industry itself, the subject of this familiarization, made impressive use of these myriad forms and genres of media delivery. We will see later that the Clinton/Lewinsky affair of 1998 was pivotal in this media merging and that sex addiction featured in the discourse surrounding the scandal. But what we are concerned with here is the public's habituation with a term, a relatively un-interrogated concept with an appeal that resided in its simplicity. What is remarkable is the ease with which ‘sex addiction’ became part of what Fedwa Malti-Douglas has dubbed (in another not unrelated context) the ‘American imaginary’.12 This process did not have the dramatic intensity of 1998, when, as it has been observed, ‘One could literally spend 24 hours a day watching, listening to, and reading about the Clinton scandal.’13 Sex addiction's media legitimation was a far more protracted affair – a drip, drip rather than John Fiske's event of ‘maximum visibility and maximum turbulence’ in his ‘river of discourses’ metaphor for media culture.14 But it did share some of that late 1990s moment's characteristics, including the unlimited number of sources with rather limited perspectives (a kind of inverse relationship between quantity and quality), and the folding of the distinctions between hard news and entertainment and producer and consumer.15 Though its genesis preceded such developments, the rise of sex addictionology was arguably facilitated by what has been called the ‘collapse of media gatekeeping’.16 Over time, it would become, like addiction culture generally, to quote Trysh Travis, ‘a matter of common sense, a concept so familiar that it seemed to evade – or perhaps not even require – definition’.17

Newsweek's cover story, we have seen, was an iconic instant. However, a better example of the phenomenon is its rival Time magazine's earlier feature at the beginning of 2011, ‘Sex Addiction: A Disease or a Convenient Excuse?’, with its follow-up piece on NBC's daily American morning TV, The Today Show, and then on the Internet on Today.com. The author of the written piece, John Cloud, started with a time-honoured technique, personalization, as he outlined the case of an individual addict, Neil Melinkovich. If the accompanying photograph of the said addict reposing in bed puzzled the reader, the reason for it soon became evident:

A difference between an addict and a recovering addict is that one hides his behavior, while the other can't stop talking about it. Self-revelation is an important part of recovery, but it can lead to awkward moments when you meet a person who identifies as a sex addict…within a half-hour of my first meeting Neil Melinkovich…he told me about the time in 1987 that he made a quick detour from picking up his girlfriend at the Los Angeles airport so he could purchase a service from a prostitute. Afterward, he noticed what he thought was red lipstick on himself. It turned out to be blood from the woman's mouth. He washed in a gas-station bathroom, met his girlfriend at the airport and then, in the grip of his insatiability, had unprotected sex with her as soon as they got home – in the same bed he said he had used to entertain three other women in the days before.

The feature was by no means an uncritical acceptance of its subject. Cloud noted both the financial and cultural implications of acknowledgement by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychiatric Disorders (DSM): ‘recognition of sex addiction would create huge revenue streams in the mental-health business. Some wives who know their husbands are porn enthusiasts would force them into treatment. Some husbands who have serial affairs would start to think of themselves not as rakes but as patients.’ He was ambiguous about definitional aspects of the alleged disease. Martin Kafka's diagnosis of the threshold of hypersexuality at seven or more orgasms a week was problematic; ‘by Kafka's definition, virtually every human male undergoes a period of sex addiction in his life. It's called high school.’ The general tone of the piece was noncommittal: ‘they are still trying to address very basic questions. Should we regard out-of-control sexual behavior as an extreme version of normal sexuality, or is it an illness completely separate from it? That question lies at the heart of the sex-addiction field, but right now it's unanswerable.’18

The video follow-up on NBC and Today.com was less guarded. ‘This disease, this particular affliction is so misunderstood’, declared ‘sex addict’ Melinkovich as he outlined marital infidelities that in his opinion became life threatening. Cloud, the Time journalist, seemed less circumspect when in front of the camera, as the segment cut to his explanation of his subject's almost hallucinatory sexual needs: ‘The urges were so strong that he was powerless to overcome them.’ The anchor's commentary referred briefly (very briefly) to critics, and immediately moved on: ‘But medical experts say sex addiction can be a serious problem.’ The item then moved to ‘Dr Jeff Gardere, Psychologist’, a widely known media medical expert, for the stereotypical seconds of authoritative sound and visuals: ‘For someone who has a real sexual addiction to the point of their being destructive in their lives there is a major treatment option available and that's checking yourself into an in-patient program that's based on a 12-step-system.’ The video was, in other words, sex addiction 101. The addict Melinkovich explained that his recovery was ‘a process that will last a lifetime…it just envelops you, it takes your being, when you're in it and you don't think you can get out, it's a very dark place’. Cloud reappeared to state that the sex addicts that he had met reminded him of drug and alcohol dependents in their descriptions of the power of their needs. Then Dr Gail Saltz, a psychiatrist and another well-known TV commentator, clarified that she saw the problem more as compulsion than addiction, ‘a compulsive, incredibly overwhelming, urge: I need to do this and it destroys their functioning, that's the operative part.’ And the programme ended with Saltz's words: ‘you keep doing it and you cannot stop’.19 The likelihood was that viewers of this item would have been left with the opinion that sex addiction was real, characterized by overwhelming, uncontrollable sexual impulses, and was best conceived and treated as an addiction, like alcoholism. The original Time article, while guarded about aspects of the diagnosis, never really questioned its ontology, and, like NBC's Today, helped to popularize the concept. An article in the Columbia Journalism Review has referred aptly to the manner in which an all-too-common, uncritical journalism has effectively fetishized sex addiction.20

Hence the term ‘sex addiction’ has become firmly entrenched in twenty-first-century popular culture. Season 1 of the UPN sitcom Girlfriends (2001) has an episode, ‘They've Gotta Have It’, that features sex addiction, when one of the principal characters, the lawyer Joan (Tracee Ellis Ross), dates a man who refuses to touch her. When confronted, he says ‘I'm a sex addict.’ She looks sceptical: ‘What man isn't?’ The man, Sean, explains: ‘I'm a recovering sex addict…Once I get turned on, there's no turning off.’ The episode also includes a scene in a sex addiction meeting. Despite the laughs (it was situation comedy), and Joan's friend Lynn (Persia White) registering positive to every item on the sex addiction self-test, and Joan's initial scepticism and recoil at the number of women that Sean had ‘slept’ with (‘almost three hundred’), sex addiction was taken seriously in the episode. As another friend Maya (Golden Brooks) says, ‘Do not take that lightly. Michael Douglas is a sex addict…It's real.’21

Sex addiction figures similarly in Charlie Sheen's comedy series Anger Management, when Charlie gets sexually involved with a recovering addict. Again the malady provokes comedy, heightened no doubt by the actor's own alleged real-life addiction, but its authenticity was never questioned: ‘She has a disease…sex addiction.’22

From its beginnings, sex addiction seemed perfectly suited to the issue-oriented format of what has been termed the ‘first generation of daytime talk shows’ (their beginnings coincided).23 We will see later that Patrick Carnes was appearing on Donahue in 1985.24 The baseball star Wade Boggs claimed that he first realized that he was a sex addict when he watched an episode of Geraldo (1989) that dealt with the subject:

I was watching Geraldo Rivera a couple of weeks ago, and there was a show on about oversexed people, and things like this, and Geraldo had psychologists on there and everything, and they were calling it a disease, and I feel that's exactly what has happened – that a disease was taking over Wade Boggs, and it just did for four years.25

Marion Barry, the disgraced mayor of the District of Columbia, was a guest on the Sally Jesse Raphael show in 1991, presenting along with other sex addicts: ‘ “You get caught up in it”, said the former mayor,…“The women. This disease is cunning, baffling, powerful. It destroys your judgment.” ’ The audience responds: ‘The audience aaahed.’ They intervene: ‘What about taking responsibility for your own damn self?’ The host glosses: ‘Our guests today say they have all brought some measure of shame to themselves and their loved ones.’ She warns, adding a frisson to the proceedings: ‘Addicts can lie…They're cunning.’26 Those who did not watch daytime tabloid television could (in this instance) read about the show in The Washington Post.27

Sex addiction was an ideal topic for a genre that thrived through exploring topical social interest problems at a personal level and which combined audience participation, indeed performance, with guest expertise and facilitated such interaction – almost a mirror image of the conceptual success of sex addiction in wider American society and culture. It dealt with sexual excess, of course, another characteristic of the talk shows. And it was therapy. Jane Shattuc estimated in 1997 that about two-thirds of the talk shows were devoted to psychological matters. A strand of therapeutic discourse was promoted by a medium known for the power of its public therapy.28

The topic was still appearing in the later generation of more confrontational talk shows. Maury presented a steady offering of sexual addiction themes based on a perceived threat to the family and in keeping with the show's penchant for marital infidelity and teenage sex: ‘My Teen Daughter is Addicted to Sex’ (1999); ‘I Need the Truth – Is My 13-Year-Old Addicted to Sex?’ (2004); ‘Take the Test! Is My Teen Daughter a Sex Addict?’ (2005); ‘I'm Addicted to Sex…I Don't Think Our 2 Kids Are Yours!’ (2006); ‘Young Teen Girls Addicted to Sex and Violence!’ (2008); ‘My Wife's a Sex Addict…Am I Her Baby's Father?’ (2010).29 Presumably the focus on female sex addicts increased the shock factor in what was often presented as a male-dominated issue.

Ricki Lake featured female sex addicts in 2004, an interesting programme because three of the four admitted to being sex addicts but were defiant about it: ‘Yes, I am a sex addict…Hi Ricki, I love your show…I don't think I have a problem.’ One woman with more than 700 claimed sexual partners responded that her only problem was that she did not ‘get enough’. Another, aged twenty-three and with a total of over 150 male contacts, said ‘Yes I am addicted to sex…I've done it with ten guys [in a day], but usually it's five!’ Only the fourth admitted to being in any kind of quandary and needing help.30 Though the first three interviewed women remained unrepentant in a loudly subversive manner (probably to provoke the engagement and controversy required of the genre), the programme was structured so it finished with the addict who was willing to enter therapy.31 The other principal participants – an ‘expert’, Catherine Burton (a Texas family and marriage therapist), and a recovered sex addict and memoirist, Sue William Silverman – were there to reinforce the problematic nature of sex addiction, to emphasize that the recalcitrant three were in denial, to advocate therapy and to ensure a master theme of disapproval – reinforced by Ricki Lake's wrinkled nose as she commented ‘Clearly she has a problem.’ Furthermore, the sex engaged in is presented as addictive, a message that was never challenged: ‘I love sex, it's like a drug to me’; ‘I have to have it’; ‘She likes sex all the time…She eats it, sleeps it, dreams it’; ‘My friend Lynette is a very big sex addict. She says that sex is like coffee in the morning for her.’32 All the tropes of sex addiction were present: the ubiquity of the malady, even in women (‘Yes, it's very common…it's not at all unusual’), acknowledging (or not acknowledging) a problem, shame (‘You have a lot of shame’), seeking self-worth from men and then feeling bad and immediately requiring another man to provide that sense of identity again, and sexual melodrama (‘A road to death’).33

Phil McGraw's talk show Dr. Phil has also included discussion of sex addiction. The ‘Suburban Dramas’ episode in 2011 featured McGraw's trademark polygraph test: ‘Brett says he's addicted to sex, online pornography and talking dirty to other women…Brett insists he's never had a sexual relationship with anyone other than his fiancée. Mandy says she doesn't believe him and wants to know if he's lying.’34 The ‘Secret Life of a Sex Addict’ episode in 2013, which had both the critic David Ley and the advocate Robert Weiss as guests, actually came out against sex addiction as the prime explanation of the subjects’ woes. Marcos had had more than 3,000 sexual partners (both male and female) in only seventeen years. His wife of nine years, Yvette (‘I didn't know he was a sex addict’), was unfaithful too: ‘I'm obsessed with hooking up with other men. I cannot maintain monogamy in a relationship with one guy. I have a wandering eye.’35 However, the experts concluded that sex addiction was the least of their problems. Dr Phil himself listed off a range of possibilities – narcissism, borderline personality disorder, anti-social personality – that might have contributed to what he termed a ‘highly dysfunctional family’; ‘Sex addiction might wind up on the list but it wouldn't be near the top.’ Yet the banner headline was ‘Secret Life of a Sex Addict’.36 The sidebars on Dr Phil's website for the shows included links to sex addiction tests and advice and support centres.

If sex addiction was ‘real’ in Girlfriends and Ricki Lake, it was positively surreal in the highly rated, adult animation South Park's sex addiction episode, ‘Sexual Healing’ (2010), which is merciless in exposing the concept's weaknesses. The nation embarks on a school-wide screening to determine how many elementary schoolchildren are suffering from the disease. They are shown a picture of a naked woman – ‘Holy moly, what's that between the lady's legs? It's all bushy…I've never seen that part of a lady! Do they all got a hedge like that? Do they?’ – and then asked what colour was the handkerchief that she was holding? ‘Did you see the bush on that lady? What the heck was that?’ Those who had not even noticed that there was a handkerchief – ‘Fuck no, I wasn't looking at a handkerchief’ – are declared to have tested positive for sex addiction and sent off for treatment; ‘It was just so big and bushy sir. Why does it look like that?’ The results of the survey are proclaimed with confidence: ‘In fourth graders, five percent of male students were found to be sex addicts. By sixth grade the number goes up to thirty percent. At high schools, nearly ninety-one percent of male students answered, “What handkerchief?”…We're facing a sex addiction epidemic in our country.’ The fourth-grader Kyle (‘Well, I just found out I'm a sex addict. I'm so scared, I haven't even told my mom yet’) is the only one to question the concept: ‘I mean, maybe this isn't really even a disease.’37

When some of the films about sex addiction are examined more closely it soon becomes evident that sex addiction has become a convenient, one might say easy, term to describe what was once termed promiscuous sex. Paul Schrader's film Auto Focus (2002) about Bob Crane, the star of the famous 1960s television series Hogan's Heroes, a man who traded on his fame to have sex with (and film) hundreds, perhaps thousands, of women before his death in 1978, was immediately classified by an article in The New York Times as a film about sex addiction. Crane was a ‘sex addict…His sex addiction overwhelmed his career’ – even though the term was never used in a film set in a period before the invention of sex addiction.38 Auto Focus is about sexual obsession, the banality of the culture of swinging, the opportunities and transience of celebrity, and the homoeroticism in heterosexual sex.39 It is a subtle film about sex and addiction that loses any analytical complexity once the two words are combined in that limiting designator ‘sex addiction’.40

The same could be said of a more recent film, Steve McQueen's Shame (2011), which appears to have prompted the earlier-mentioned article in Newsweek – an interesting example of the circularity of popular culture – written, significantly, by the magazine's entertainment reporter.41 Shame's director Steve McQueen and co-screenwriter Abi Morgan have said that the initial idea for the project came from a conversation about sex addiction, that they talked to ‘sex addicts’ in their preparatory research, that the film's title came from a word frequently used by those addicts, and that it is about a man who used sex in the same manner that others used alcohol. Despite his recognition that it was a ‘grey area’, the film's main actor, Michael Fassbender, also consulted a ‘sex addict’ in preparation for his role. Clearly, the creative team thought that sex addiction was genuine – McQueen: ‘sexual addiction is real’ – and when interviewed invoked several of sex addiction's keywords: ‘shame’, ‘compulsion’, ‘self-loathing…the shame that these people talk about’ and ‘lack of intimacy’; ‘Brandon is a sex addict. He has problems with intimacy…That's classic sex-addict behavior.’42 The scene in Shame where Brandon purges his pornography collection is a recurring sex addiction trope.43 The hinted (past or looming) incestuous relationship with his sister in the film was perhaps prompted by the sex addiction literature's suggestion of sexual abuse as a contributor to the malady, though it is not an aspect of the film that has been much discussed. In the printed version of his Sight & Sound interview with Nick James, McQueen descended into exaggerated stereotypes that could have come (probably did come) straight from a sex addiction advice book when asked what the tipping point was between promiscuity and addiction: ‘When you find that in order to get through a day, someone is on the internet for 20 hours a day or more looking at pornography or having to have a sexual activity at least ten times a day, it's incredible.’44 His reported discussion in Newsweek was positively hyperbolic: ‘It's not like alcoholism or drug addiction, where there's some built-in sympathy. It's almost like the AIDS epidemic in the early days. No one wants to deal with you…You're a fiend. That stigma is still attached.’45

It is intriguing that Shame is far more nuanced than that. Brandon does not spend most of his day on the Internet and does not have ten-times-a-day sex. The terms ‘sex addict’ or ‘sex addiction’ never appear in either film or script. The word ‘shame’ is also absent from the film (apart from its title) and only occurs twice in the script in narrative descriptions: once when the protagonist Brandon (Fassbender) looks in the mirror ‘full of shame’ after his sister has discovered him masturbating (the mirror-looking does not occur in the film), and then after anonymous sex in a hotel room when ‘HOTEL LOVER’ pulls on a ‘tiny thong’ and Brandon ‘looks away, fighting back the cold flutter of shame’ (the tiny thong and cold flutter are also absent from the moving image rendition).46 It seems more a film about the contemporary world, the current era of on/scenity referred to earlier, where sex has become quotidian. This is captured perfectly in several sections of the film. One is in the lingering looking that begins and ends the narrative – framing the film – the mutual staring on the subway train that might have led to something more between Brandon and ‘PRETTY SUBWAY GIRL’.47 Another sexually evocative moment occurs when Brandon (and the viewer) gaze upwards to a full-length apartment or hotel window with a naked woman facing outwards, her hands and body pressed against the glass, being fucked from behind. The silence of this watched encounter adds to its distancing.48 Elsewhere, the noise-scapes of sex (the groans, grunts, gasps, laboured breathing and whispers, the muffled computer porn) are as important as the Bach in the film's soundtrack. It is a masterly filmic portrait of a sexualized society.

Shame is also about the Internet's facilitation of that easy sexualization. The film could almost have been called ‘Porno’. McQueen juxtaposes Brandon's boss David's use of the Internet to chat to his son on Skype, retaining everyday family contact, with Brandon's employment of the same medium to access porn and to participate in online sex. Brandon's consumption of online porn is certainly central to several of the movie's scenes.

Your hard drive is filthy, all right. We got your computer back. I mean, it is, it is dirty, I'm talking like hoes, sluts, anal, double anal, penetration, inter racial facial, man, Cream pie. I don't even know what that is…It takes a really sick fuck to spend all day on that shit:

David's monologue is interrupted by his son, still on Skype, ‘Daddy…Daddy’.49 Later, when Brandon's sister Sissy (Carey Mulligan) opens his laptop she discovers a series of windows, a

blurred smorgasbord of porn sites, graphic and obscene, their colors reflecting across her face and body. An escalating collage of graphic images, obscene sexual messages and a provocative sexual conversation hanging mid sentence addressed to a live sex chatroom. The images haunting, brutal, from the weird to the sadomasochistic. The open windows, an endless stacking of obscene chatroom conversation, emails posted with graphic sexual photos and live webcam images of every combination of fucking disappearing into the screen in infinite form.50

That is in the script. This kaleidoscope of sexual imagery did not make it to the screen. But the live webcam scene survives as a panty-clad beauty beckons Sissy from Brandon's laptop: ‘Hey, where's Brandon? Are you Brandon's girlfriend? Do you want to play?…Do you wanna play with my tits? I know Brandon would really like it…And I know exactly what Brandon likes.’51 In discussion McQueen stated that Shame is about ‘our relationships with sex and the Internet. It's about how our lives have been changed by the Internet, how we are losing interactions…We've been tainted, it's unavoidable.’52 One of the starting points for his interest in the film, he explained in a press conference for the British Film Institute (BFI) London Film Festival in 2011, was the contemporary ‘accessibility of sexual content’.53

Shame is also a film about casual sex in twenty-first-century New York, where sex is just sex, readily available, and without commitment (Brandon's longest relationship is four months). He engages in a series of escalating, paid and unpaid encounters involving nameless women, a man, and a threesome with two women. The close-ups of wedding rings convey the message that it is not just singles involved in this culture. David (James Badge Dale), who fails and then succeeds in such encounters, is, as Brandon reminds his sister Sissy, married: ‘You know he's got a family, right? You know he's got a family?’54 (Of course uncommitted sex is especially available if you look like Michael Fassbender. One of the film's collusions with the very culture that it is allegedly critiquing is that all of those engaged in such sex, even when it is being paid for, are always so desirable: the script refers to ‘PRETTY SUBWAY GIRL’, ‘PRETTY ASSISTANT’, ‘ATTRACTIVE WOMAN’, ‘CUTE NEIGHBOR’, ‘A stunning leggy COCKTAIL WAITRESS’, ‘HOT GIRLS’.55)

So Shame could also have been called ‘Promiscuity’, though that would have had an outdated feel and might not have conveyed the intensity and compulsion that McQueen envisioned. But whatever the intentions of its makers, it seems more about alienation or ennui than addiction. Brandon's sadness is conveyed, hauntingly, in the window shot after he fails in what might have been committed sex with his colleague Marianne (Nicole Baharie), but the next moment he is engaged in vigorous sex against the same window with an unnamed woman.56 His suppressed anger, his self-destructive impulses, his sheer desolation, build in brilliant editing – standing in the subway train, in the darkened street, fingering a woman in a bar (‘I want to taste you…slip my tongue inside you…just as you come’), tasting his fingers, being beaten by her boyfriend, engaging in gay sex, the threesome, woman kissing woman, prolonged fucking, brutish facial contortions to the point of exhaustion – as the film reaches its climax with Sissy's bloody anguish and Brandon on his knees in torment, in the rain, sobbing. But then the film ends as it had begun with the attractive woman on the subway, the longing looks, the wedding ring. Perhaps it will all begin again. Sukhdev Sandhu came closest in his review in Sight & Sound when he described Shame as depicting sex addiction as ‘a species of anomie’.57

Yet much of the coverage of Shame has persisted with that restricting ‘sex addiction’ billing: ‘The acclaimed new film Shame portrays the harrowing world of sex addicts’ (The Guardian); ‘chilling story of a New York sex addict’ (The Observer); ‘Sex Addiction and the City’ (Newsweek).58 Robert Weiss thought it ‘a dead-on portrayal of active sex addiction’ and worried that some of its scenes might ‘trigger a sex addicted client's desire to act out’!59 The classification could even survive content that suggested that Shame was about something else or more. Thus Mark Fisher in Film Quarterly declared McQueen's creation ‘a study of sex addiction’ and wrote of ‘sex addict Brandon’ while he simultaneously referred to ‘such an overwhelming sense of affectlessness that it could be about depression as much as sex addiction’.60

The incongruity of Shame is that the subtlety of its exploration of what its creators have persisted in labelling as sex addiction exposes the limitations of other representations of this supposed complaint – including the shallowness of the concept itself. We do not need sex addiction to explain Brandon's world.

Sex addiction has certainly featured in some forgettable cinema. In Joseph Brutsman's truly awful Diary of a Sex Addict (2001) we follow the exploits of sex addict Sammy Horn (yes, Horn), a restaurateur and chef in his fifties (one online reviewer referred to him unkindly as a pensioner), who recounts his exploits to his therapist (Nastassja Kinski) as he takes us through a seemingly never-ending, five-day parade of thrusting sex (Sammy does not believe in foreplay) with improbably beautiful, female sexual partners. Sammy, played by the woeful Michael De Barres, is a kind of Jekyll-and-Hyde character – sexual addiction of the most basic kind – whose saccharine, family-devoted Dr Jekyll (‘I love my wife’, ‘I love my [young] son’) is even worse than the sex-addicted Mr Hyde. An IMDb.com reviewer, who described it as a B-grade sexploitation film attempting to ‘masquerade as a study of sexual addiction’, captured its nature perfectly. But with Rosanna Arquette and Kinski as stars, this softcore pornographic film/video/DVD, best classified as unintentional comedic drama, is still an example of the popular familiarization, if not legitimation, of the concept of sex addiction.61

I Am a Sex Addict (2006) is more memorable (see Figure 6). Caveh Zahedi's whimsical, low-budget, ‘fictionalized documentary’ is about this Woody Allen-like independent filmmaker's long-running obsession with prostitutes. He is a sex addict with honesty, who insists on telling his girlfriends about his problem and musing about the ethics of prostitution: ‘I had always considered myself a feminist’. It is never clear how seriously we are supposed to take his addictions – repeatedly asking street prostitutes ‘Will you suck me?’, grabbing the breasts of massage parlour receptionists and then fleeing, masturbating in the confessional – but the film narrative is framed by Zahedi's attendance at sex addiction meetings and ends with the claim that he is cured.62

Thanks for Sharing, a film that was in production when we first began work on this project and out on DVD by the time our book was completed, is certainly a film about sex addiction – undigested, unquestioning sex addictionology straight from Patrick Carnes's A Gentle Path Through the Twelve Steps and Out of the Shadows, which appear, almost like clumsy product placements, in several scenes in this (for these writers) irritating romantic drama. Set in the context of a sex addiction support group, and starring some well-known names (Tim Robbins, Mark Ruffalo and the singer Pink play the addicts, and Gwyneth Paltrow and Joely Richardson are among their loved ones), the film rehearses all the themes of addictionology. Indeed it follows the format of Alcoholics Anonymous a little too closely with its meetings, sponsors, sponsees, fellowship, sobriety medallions (ambiguously, ‘freedom from masturbation and sex outside of a committed relationship’), and frequent references to ‘sharing’ (hence the film's title), ‘one day at a time’, ‘Friend of Bill’ (recovering alcoholic), and invocation of ‘a higher power’.63 The concept of the partner as co-addict also features, with Katie (Richardson) advising Phoebe (Paltrow) that as a partner she consider ‘What are my issues that I have to deal with? After all, I picked an addict.’64 Alcohol and drug dependency intersect with sex addiction throughout the film to convey the nestling theme discussed elsewhere in this book. Mike (Robbins) is a recovering alcoholic and sex addict. Dede (Pink: Alecia Moore) is in a Narcotics Anonymous programme as well as attending the sex addiction group (‘The only way I know how to relate to men is sex’).65 Phoebe's ex-boyfriend was an alcoholic and she is a fitness fanatic with food issues. Neil (Josh Gad) is both a food and sex addict. It seems ironic that Edward Norton, who plays the self-help- and group-therapy-obsessed narrator in the movie version of Chuck Palahniuk's satirical Fight Club (1999), was one of the executive producers of Thanks for Sharing.

There are hints of a counter-narrative. Neil lies to the group. Phoebe's double mastectomy and recovery from cancer are juxtaposed with Adam's (Ruffalo) rather obsessive five-year sobriety (televisions are removed from hotel rooms to eliminate any likelihood of sexual stimulation). The drug addiction of Mike's son Danny (Patrick Fugit) actually serves to contrast the seriousness of his habit – and ability to overcome it alone – with the triviality of the sexual dependency of the main protagonists and their inability to combat it without group help. The viewer may also wonder what the frotteurism and up-skirt voyeurism of Neil (and uncomfortable sexualized relationship with his mother) and the obvious childhood sexual abuse of Becky (Emily Meade), one of Adam's casual contacts, have in common with the promiscuity of Adam, Mike and Dede.

Then there is the archetypal tension between sex addiction's anti-sex message and the sexualization of elements of its message that will be discussed later in this book. Paltrow's objectification is blatant. A clip of her stripping was used to market the film – one journalistic puff-piece mused whether the clip would promote a fresh outbreak of sex addiction in New York – and her publicity interview on the talk show Chelsea Lately managed to focus on her body (‘what a vision…thank you for showing your body in this movie because you're naked a lot’) while almost totally avoiding any discussion of sex addiction and with only fleeting reference to the actual film that she was ostensibly promoting (see Figure 7).66

Yet the directorial message in Thanks for Sharing is unmistakable: sex addiction is a genuine disease. Adam says ‘I have to remind myself every day where this disease could take me.’ ‘That's the disease. It makes you do things that violate everything that you believe in.’ The character Mike puts it more bluntly – ‘This disease is a fucking bitch’ – and makes it clear early in the film (counter to his son's message) that giving up alcohol was easy compared to shedding his addiction to casual sex. ‘This thing is a whole different animal. It's like trying to quit crack while the pipe's attached to your body’ (a simile that does not really bear deeper analysis). The seriousness of their malady, ‘the darkness’, is constantly impressed. Adam's lack of access to a laptop (odd, given his occupation as an environmental consultant: a blocked MacBook Air is specially brought in by an assistant so that he can Skype Phoebe while on a business trip!) is ‘saving his life’. ‘You think I like not having a television or a laptop? It fucking blows. But guess what? It's saving my life, so I do it.’ Dede's counselling would supposedly save her from suicide: ‘There's gotta be another way. There has to be, or I'm gonna fucking kill myself.’67 This sentiment echoes the addictionology language of sex addiction as not only a disease but a progressive and fatal one.68

The film's earnestness has convinced commentators who do not share the scepticism of the authors of this book. The movie columnist for the Chicago Sun-Times wrote that the film made a ‘convincing case’ for sex addiction, ‘makes you care about sex addicts’.69 The reviewer for The Washington Post thought that the film and its script took seriously the idea that ‘sex addiction is a real illness’ and showed ‘real respect for the power of these programs’.70 These were surely understatements given that Carnes himself might almost have written the screenplay. Weiss, the founder of the Sexual Recovery Institute in Los Angeles, and Carnes-trained, highly recommended Thanks for Sharing to ‘therapists interested in what sexual recovery looks like’.71 The most nauseating instance of the film's endorsement of addictionology is in its closing moments when Billy Bragg's song Tender Comrade (1988), a poignant, homoerotic homage to returned, working-class, British soldiers, is played to evoke battle-weary, male camaraderie in the wake of the fight against sex addiction – as if those struggling against sexual urges are in any sense comparable to those engaged in mortal combat.

Even when the references to sex addiction have been humorous or mocking they were still invoking the concept. Victor Mancini, the main character in Chuck Palahniuk's novel Choke (2001), is a sex addict who has sex with the female addicts whom he sponsors – in toilets, in a janitor's closet – while meetings are in progress. He never advances beyond the fourth of the Twelve Steps, the listing of his sexual contacts, and he treats sexaholics’ meetings as ‘a terrific how-to seminar. Tips. Techniques. Strategies for getting laid you never dreamed of. Personal contacts.’ ‘Plus the sexaholic recovery books they sell here, it's every way you always wanted to get laid but didn't know how.’ He hangs about in the recovery section of bookshops to pick up female sex addicts. It is a hilarious novel about casual sex (‘her name's Amanda or Allison or Amy. Some name with a vowel in it’) that positively revels in its subject matter, but with serious things to say about the addiction industry and American culture. And not just sex with women:

We don't need women. There are plenty of other things in the world to have sex with, just go to a sexaholics meeting and take notes. There's microwaved watermelons. There's the vibrating handles of lawn mowers right at crotch level. There's vacuum cleaners and beanbag chairs. Internet sites. All those old chat room sex hounds pretending to be sixteen-year-old girls. For serious, old FBI guys make the sexiest cyberbabes.72

Its message is the antithesis of everything that believers in the concept of sex addiction hold dear: ‘The magic of sexual addiction is you don't ever feel hungry or tired or bored or lonely.’73 When the film from the novel appeared in 2008, its distributors (in the spirit of Palahniuk) promoted it with gifts of anal beads.74

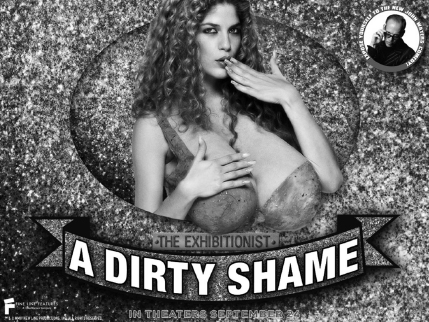

Similarly, John Waters's outrageous comedy A Dirty Shame (2004) (see Figure 8), in which a Baltimore suburb is taken over by sex addicts – ‘Straight, gay or bi, there's a new sex act just waiting for you. Sex for everybody! Fuck your neighbors joyously…Let's go sexing’ – could hardly be said to take the subject seriously.75 Sex addiction in this film is always the result of concussion, a rather quaint nod in the direction of nineteenth-century, physiological explanations of hypersexuality that modern believers in the malady are hardly likely to endorse. Nor are they likely to be amused by the flippant portrayal of their problem (‘I'm a sex addict too. I'm a cunnilingus bottom, and I'm your mother…Let's go down to the Holiday House and fuck the whole bar. Okay, Mom. Let's go sexing!’) and their meetings (‘My name is Paige, I'm from Roxton and I am a sex addict. My drug of choice…frottage…“Excuse me”, I'd say, while I'd grind my crotch into an unsuspecting passenger on a crowded airplane’).76 When asked if he had attended Twelve-Step meetings in preparation for his film, Waters reportedly replied: ‘I felt that would have been condescending…But if I were a sex addict, I would definitely go to sex addiction meetings, and for the same reason that they do in this movie – someone's going to slip.’77

And yet as Patrick Carnes reportedly observed, ‘The fact that pop culture is making jokes about sex addicts is a sign that awareness of the condition is percolating in mass consciousness.’78

One television series that seems deliberately to have avoided invoking the concept – despite media stories doing it for them – is Showtime's Californication (Seasons 1–7, 2007–14). Season 6 began with the main character, womanizing writer Hank Moody (David Duchovny), sent to the wryly named rehab facility ‘Happy Endings’. Despite his numerous sexual encounters and the way his sexual behaviour impacts negatively on his life, writing, friends and family, Hank is never described in the series as a sex addict: he is in rehab for his drinking. The absence of the label of sex addict is all the more striking because the actor Duchovny has reputedly been treated for sex addiction. Californication is strident in allowing Hank (in line with most of the other characters) his sexual proclivities (‘holes is holes’) without judgement, though definitely with consequences for the life he thinks that he wants. The characters are framed as creatures of excess, instant gratification, opportunism and a debauched Hollywood lifestyle. Even his fellow rehab inmate, the character listed as ‘Tweaker Chick’ in the credits (Angela Trimbur), is not described as a sex addict in either the dialogue or the credits, despite her sexual exploits: she shoves Hank's hand down her pants at the end of a group therapy session and then has non-consensual sex with him while he is asleep. Sexually inappropriate and aggressive, ‘Tweaker Chick’ screams ‘I want drugs’ as she leaves Hank's room, raising the possibility that she, like Hank, is in rehab for substance abuse, with her sexual behaviour not under scrutiny.79 When Hank returns to rehab (to sneak drugs in) and sees her again, he good-naturedly says ‘hello rapist’ as she straddles him, gyrating and pleading ‘Feed me some fuckin’ inches dude.’80 The drugs that Hank brings into rehab fuel a sexually charged party. The message seems to be that, given the opportunity, anybody (in or out of rehab) will engage in polyamorous sexual encounters. This is a message about excess and access rather than addiction.

Some material should not be taken seriously. Dr. Drew's Sex Rehab (2009), three weeks in the Pasadena Recovery Center under the care of Dr Drew Pinsky, is entertainment rather than treatment, its format, editing, casting and much else determined by the parameters of reality TV, the genre that combines documentary and soap opera, reality and unreality, where viewers look for glimpses of authenticity amidst all the acknowledged, staged fakery.81 Significantly, Dr. Drew's Sex Rehab is a spinoff from Celebrity Rehab with Dr. Drew (2008–12). The patients (cast) of porn stars and former porn stars, models and ex-models, a (minor) rock star and a pro-surfer were hardly randomly selected – the women had the same agent and the surfer, allegedly, was paid for product endorsement (which may explain the frequent clothing changes, his mismatching sneakers – ‘Interesting shoes’ – and the fact that he brought his surfboard with him to the treatment centre!), and were either self-declared non-addicts (the 3,000 women that the rock star slept with were a potential part of any performer's CV) or multiply addicted (sex being the least of their worries). Amber Smith was addicted to antidepressants and opiates. Kari Ann Peniche was a methamphetamine addict. Drummer Phil Varone had a cocaine dependency, as did Nicole Narain, a former Playboy Playmate. Several became almost professional celebrity addicts: Jennifer Ketcham, Peniche and Kendra Jade Rossi would also appear in Sober House, Season 2 (2010), and Peniche (again) in Celebrity Rehab, Season 3 (2010). Smith had already featured in Season 2 of Celebrity Rehab (2008) and Season 1 of Sober House (2009). One of those ‘treated’, Duncan Roy, a gay English film director who had some knowledge of production, wrote later of blatant playing to the camera, that he was concerned that some ‘might not be on the show for the same reasons as I was. That they might not have any desire for sexual sobriety. That I might be part of a huge pantomime.’82 Rossi blogged that when she signed up for the show it was for the money and she did not know what sex addiction was.83 Varone recalled that his agent phoned and said

‘OK, we have a supermodel, we have a porn star, we have a Playboy Playmate, we need a rock star.’ They need this cast. Do you want to do it? And I said, ‘Well to be on television I guess I will.’ That's the decision. Those shows are scripted out a certain way.

He did not consider himself a sex addict; he just had access to a lot of groupies and took advantage of it.84 After the show he produced his own sex DVD, The Secret Sex Stash, and commercially manufactured a dildo replica of his penis called the ‘phildo’: not much shame there.85

It is all staged. The mise en scène is sexualized in ways totally incongruent with the declared aims of detox. The publicized three weeks of celibacy (including no masturbation), the very public confiscation of sex toys, the ban on digital contact with outside temptations (cell phones, laptops, tablets) only serve to heighten the flirting, sexual innuendo, flaunted cleavages, the very sexualized avoidance of sex by those who include porn stars whom the viewer may well have seen elsewhere engaged in very explicit activity – why else would the producers want such actors!86 Gareth Longstaff has argued that when the former reality TV celebrity Steven Daigle became a porn star, the visual techniques of reality TV merged with those of pornography: ‘the mixture of intimacy, liveliness, extreme-close-up, amateur and hand-held camera work, and surveillance imagery associated with the visual rhetoric of both Reality TV and pornography were reworked and repositioned as dual markers of both reality and fantasy’.87 With the female porn stars in Sex Rehab the movement is in the opposite direction, a fascinating example of the intertextual relationship between pornography and sex addiction that we will return to later in the book. Unsurprisingly too, given the presence of those porn stars, there are many emotional ‘money shots’, those moments of raw feeling – crying, rage – integral to the talk show and reality TV, named by Laura Grindstaff after pornography's famed ejaculatory money shots, visible signs of pleasure rather than grief.88

It is perhaps appropriate that reality TV, a media form that our colleagues Misha Kavka and Amy West have characterized as standing outside history to achieve emotional intensity and immediacy, should, in this case, have been promoting a concept (sex addiction) whose proponents, we are arguing, have been so lacking in historical awareness.89 But the point with this, and other such television, is that it was publicizing the concept. As a blog for the show put it: ‘I think after watching this show, a lot of people are going to think, “Am I a sex addict?” ’90

We have been focusing on the sometimes-dramatic examples of film and television to explain the dissemination of an idea. Yet the quiet insinuation of the concept is perhaps best illustrated by its acceptance by the humble library cataloguer. The Library of Congress established ‘sex addiction’ as a new subject category in 1989 (revised in 1997) alongside a long list of variants: ‘Addiction, Lust’; ‘Addiction, Sex’; ‘Addictive sex’; ‘Compulsive sex’; ‘Erotomania (Hypersexuality)’, ‘Hypersexuality’; ‘Lust addiction’; ‘Obsession, Sexual’; ‘Sexaholism’; ‘Sexual Addiction’; ‘Sexual compulsiveness’; ‘Sexual obsession’.91 Libraries throughout the world are now able to use these influential Library of Congress subject headings in the cataloguing of their own holdings.

This infiltration may have been unproblematic for nonfiction. It may even be of some utility where sex addiction is a legitimate component of the subject matter of some fictional forms: McQueen's Shame and Waters's A Dirty Shame appear as ‘Sex addiction – Drama’ in the University of Melbourne Library Catalog. Murray Schisgal's Sexaholics (1995), first performed at the 42nd Street Workshop Theatre in New York in 1997 and now part of ProQuest's Literature Online, is in fact about sexual addiction. The play's two acts are framed by a couple's unlikely off-stage attendance at an addicts’ support group after an episode of energetic casual sex:

These people…They meet a couple of nights a week and they discuss their problems and they help each other, they help each other to stop ruining their lives…The idea is the same for all addicts. And it works. It works because we also have a sickness over which we have no control. For weeks I've been trying to get together the courage to go to a meeting. There's one tonight. If…If you'd go with me …92

John Franc's Hooked: A Novel (2011), about a group of male friends visiting brothels, at least contains fleeting reference to the syndrome. But it is more concerning when the term is used to classify any work that contains multiple or non-monogamous sex. Novels as various as Patrick McGrath's Asylum (1997) (obsession), Pier Paolo Pasolini's Petrolio (1997) (perversity and fascism), Stephanie Merritt's Gaveston (2002) (infatuation), Howard Jacobson's Who's Sorry Now (2002) (infidelity) and Kathryn Henderson's Envy: A Novel (2005) (grief and transgression) have all been catalogued as fiction about sex addiction when they are not about sex addiction at all and the words never appear between their covers other than, perhaps, in the Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data after the title page.93

One of the more intriguing effects of this phenomenon has seen the reclassification of the reprints or newer editions of older classics under the term ‘sex addiction’ – Djuna Barnes's Nightwood (1936), Paul Morand's Hecate and Her Dogs (1954, 2009) and Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita (1955, 1958) are jarring examples.94 Our own University of Auckland Library lists the 1995 edition of Philip Roth's controversial Portnoy's Complaint (1969) under the subject heading ‘Sex addiction – Fiction’ despite the fact that sex addiction did not exist in 1969 and Roth does not use the term in the novel. Such retrospective classifications superimpose narratives different to those envisaged by their authors, essentially dehistoricizing these works.95

Any literary masterpiece about uncontrolled passion, sexual fixation or unconventional sex is in danger of being classified under the reductive term ‘sex addiction’. This was the fate of Oscar Hijuelos's stunningly vibrant The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love (1989). The sexual conquest and longing, the masculine posturing and vulnerability, only part of a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel that was about so much else, was enough for an influential text on addictive disorders to condemn it as a case study of sex addiction; the novel's central character, the philandering musician Cesar Castillo, is a sex addict.96 Life is effectively squeezed out of the work.

Since Janice Irvine's initial analysis of the place of sex addiction in modern American sexual history, then, the phenomenon has become the default explanation for any kind of promiscuous or obsessive sexual interaction. Jesse Fink, who (we will see later) went on a ‘three-year sex binge’ with hundreds of women and who wrote about his activity, said that his memoir was promoted as sex addiction against his better judgement. The publisher characterized him as a sex addict but he did not see things in that way and thought the concept, in typical Australian style, ‘a crock of shit’. He said that dating four or five women a week in this Internet age was not unusual and certainly not indicative of any addiction.97

When Erica Jong published Fear of Flying in 1973 – with its famous zipless fucks – her female protagonist Isadora Wing (Jong) may have had ‘Nymphomania of the brain’ and have been ‘a nymphomaniac (because I wanted to be fucked more than once a month)’ but she was definitely not suffering from sexual addiction.98 In 1990, however, Wing, now the central character in Jong's Any Woman's Blues, ‘a fable for our times’ according to its fictitious editor, is indeed ‘a woman lost in excess and extremism – a sexoholic [sic], an alcoholic, and a food addict’.99 The Twelve Steps, AA meetings, frequent references to obsession and addiction are integral to her story:

Sex was what blotted out the world for me. Sex was my opium, my anodyne, my laudanum, my love. Sex was what I used to kill the pain of life – the pot and the wine were just my avenues to bed. Open your mouth and close your eyes. Open your legs and close your eyes. Open your heart and close your eyes…I lived for sex, for falling in love with love, for breaking (or at least collecting) hearts.100

Alcohol addiction and sexual addiction are intertwined in Any Women's Blues. ‘The Program is like Mary Poppins's elixir: it becomes the specific medicine for whatever ails you. You ask for a cure for sex addiction? You got it.’101 Wing uses AA as a (not exactly successful) way to battle her sexual obsessions. ‘I drew the line at Sexoholics Anonymous. For one mad moment, I thought of going to Sexoholics Anonymous to meet men, but I couldn't quite bring myself to. The very notion made my mind giggle.’102 Irvine rightly referred to this work by a best-selling author as evidence for the popularization of the idea of sex addiction.103 Works such as Jong's both reflected and facilitated this cultural spread.

However, the story did not finish there, for in 2011, as part of the publicity accompanying the republication of her bestseller, Jong decided retrospectively that Fear of Flying had been about sex addiction after all. Both the early Wing and her creator are sex addicts: ‘That was my life. I had been a sex addict, a man addict.’ Needless to say, in this age of consolidation of the concept, sex addiction was part of the billing. The piece in The Huffington Post was called ‘Erica Jong on Feminism, Sex Addiction and Why There Is No Such Thing as a Zipless F**k’.104

Sex addiction has become part of popular culture. That is why Junot Díaz's character could trot it out as one of his lame excuses in a novel in 2012 in the epigraph to this chapter.