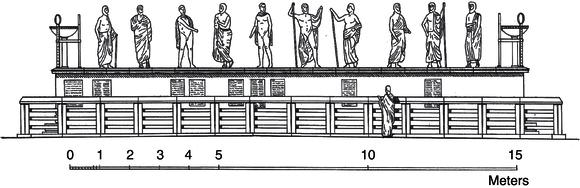

Figure 10.1 Drawing of a reconstructed allotment machine (klērotērion). Courtesy of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations.

Plato was in no doubt about the deleterious effect of democracy on Athenian communal life.

[In a democracy] men are free, and the city is full of freedom and free speech. Indeed, in a democracy there is license to do whatever one wants…There is no compulsion to hold public office in such a city-state, even if one is capable of it. Nor is there any need to submit to rule, if one does not want to. Nor must one fight, when others are fighting [in defense of the city], nor to make peace when the rest are concluding a peace, if one does not feel like it… The climax of liberty of the masses in such a city-state is when bought slaves (male and female) are no less free than those who purchased them. Furthermore – I almost forgot to mention – there are equal rights and freedom in relations between men and women! (Plato Republic 557b–63b)1

On the other hand, Thucydides presents a speech purportedly delivered by the great democratic statesman Pericles that extols the benefits of democracy on civic order:

We participate in public affairs freely and in regard to suspicion towards one another over our day to day lives, we do not look askance at anyone if he enjoys himself. Indeed we associate with one another without hostility in our private affairs and, because of fear, we do not break the laws in public affairs. We always obey those in office and the laws, especially those that have been established to aid those who have been wronged as well as those unwritten laws which bring public shame on those who transgress them. (Thucydides History 2.37)

How do we reconstruct the historical reality behind, on the one hand, the clearly hostile account of an embittered member of the elite like Plato, and the idealizing nature of Pericles’ speech? Was democratic Athens an anarchic free-for-all, or was it an orderly society with great respect for both individual freedom and the laws? In short, what was the lived experience of an Athenian citizen under the democracy and how might we best grasp it 2,500 years later?

Scholars have approached this question in different ways. Some have focused on institutions and argued that the best way to understand the impact of democracy on communal life is to study the complex machinery of the democracy. This approach has been championed above all by Mogens Hansen and Peter Rhodes. Their many studies of institutions such as the Assembly and the Council have shown us not only how sophisticated the institutional design of ancient democracy was but also have made us more attuned to the development of these institutions over time.2

Other scholars, most notably Nicole Loraux and Josiah Ober, have focused on the animating ideals of the democracy and argued that communal relations were largely shaped by the articulation and negotiation of these ideals in public speech. These scholars propose that we can best understand the democracy by looking at the way that relations between (for example) private and public, rich and poor, elite and masses were conditioned by democratic ideals as articulated in public contexts.3

Finally, a third group of scholars have examined the social and cultural life of the democracy: the buildings and monuments as well as the religious rituals, processions, and festivals that instantiated democratic ideals and contributed to democratic experience. As many have noted, it is perhaps not coincidental that the Athenians boasted of having more festivals than any other city and also produced works of high literary, historical, and philosophical value that are unrivalled by any other city.4 While much of this cultural production and social activity was created by and for citizen men, scholars have not failed to notice that women played a prominent part in the ritual life of the community, especially in civic religion. Furthermore, women figure prominently in the social imaginary of much of the literature of the democracy, despite their lack of full political rights. Some scholars, therefore, have investigated the significance of the fact that women were marginal to the democracy in institutional terms, yet vitally central in ideological terms.5

The investigation of the lives of women under democracy has been paralleled by the examination of other “marginal” groups, especially free non-citizens (metics) and slaves.6 It is noteworthy that in Athens these groups emerged in tandem with the rise of democracy and reached numbers unparalleled by any contemporary Greek city-state. Since metics and slaves played an important role in the economy (agriculture, manufacturing, and trade), not to mention warfare, scholars have investigated not only the social impact of these groups on the democratic polis but also the impact of democracy on these groups. One of the striking recent findings in this branch of research is that while in formal legal and ideological terms there was a strict division between male citizens and these other groups (women, metics, and slaves), the lived reality seems to have been quite different.7 Indeed, it could be argued that in social terms the Athenian democracy was a more diverse and free society than had ever existed before. It was precisely this social freedom between genders and social classes that so disturbed Plato (quotation above). It seems that the democratic principles of freedom and equality, so vociferously defended among citizen men in the formal political institutions of the state, did indeed “trickle down” to other social groups. Taking up this point, I shall argue that democracy had a significant impact on the character of the whole community, not just on the narrow group of male citizens.8

I will survey the areas mentioned – institutions, ideals, culture, and society – in order to explore the impact of democracy on communal life. It should be obvious already from the brief overview presented above that consideration of each of these areas is necessary to achieve a balanced view of ancient democracy. I will demonstrate that the democracy created new institutions that changed the ways the Athenians associated with one another, and show how they forged new and strikingly sophisticated concepts of freedom, equality, and free speech. I shall also stress, however, that despite such innovations, these ideals and institutions developed from pre-existing practices and values and, more importantly, that earlier ideals and practices that pre-dated the democracy were not wholly erased by the institutions of democracy.

Although political assemblies of adult males had been held at least since the time of Homer (eighth century), it was with the advent of democracy in Athens in 508/7 that the assembly of the people, rather than magistrates or councils, became the primary locus of power.9 This is not the place to discuss the causes and stages of this momentous shift in power from a narrow circle of elite persons to the people.10 For our purposes, what is important is the impact of this change on the ways that ordinary Athenians engaged in communal life. In Archaic Greece (eighth to sixth centuries), assemblies seem to have been summoned irregularly to test public opinion on important matters affecting the community (especially war), whereas most actual decisions were taken by elite leaders gathered together in a small council. By contrast, under the democracy all matters had to be brought before the full assembly of adult male citizens for debate and decision (Herodotus 3.80.6). The first important effect of democracy on the lives of ordinary Athenians, therefore, was the need and opportunity for regular participation in the political decisions by which the state was governed and its policies determined. It is this opportunity to participate in politics which Thucydides signals as a hallmark of democracy in the claim that the Athenians “participate in public affairs freely” (2.37.2), and Aristotle later theorizes as a key aspect of the freedom that is the basis of all democratic constitutions (1317a40–b1).11

With the increase in the importance of the collective assembly under the democracy came formalization of the rules by which it was ordered. Regular meetings (forty per year) were now held, and the occasions for certain decisions were fixed in the political calendar (Ath. Pol. 43.3–6).12 The right to attend the assembly was restricted to citizens, and citizenship was limited to a relatively small number of adult males (approximately 30,000) who could claim descent from Athenian parents. Accordingly, new formal procedures for determining citizenship were developed: instead of the associations of fictive blood relatives known as phratries (“brotherhoods”; see Lambert 1993; Jones 1999: 195–220), it was now the local assemblies held in each of the 139 newly formalized administrative districts known as demes (Whitehead 1986) that were responsible for accrediting the citizenship of each member through collective vote (Ath.Pol. 42.1–2). The procedures of these demes therefore mimicked those of the larger polis community and added a second venue for political participation by ordinary citizens. On both the polis and deme levels, these assemblies probably replaced older village meetings, but their new importance in the machinery of the democracy demanded a more regular schedule of meetings and more formal procedures.13 In this sense, demes prepared citizens for their civic functions at the polis level, and therefore effectively served as “grassroots democracies.”

The requirements for citizenship were male gender, the age of eighteen years or above, birth from a citizen father (up until 450) and birth from citizen parents (after 450).14 Paradoxically, the limitation of citizenship to those with parents on both sides gave new prominence and importance to citizen women (Cohen 2000: 30–40; Blok 2005) but also led to restrictions on their freedom of movement and lifestyle (Cohen 1991). Since Athenian men needed to be sure of the paternity of their children, it became more important to ensure the sexual fidelity of their wives. Athenian women, in consequence, became subject to stricter norms of gender segregation under the Athenian democracy than they were in other Greek communities (Jameson 1997: 96). As suggested above, however, the lived experience of women did not always conform to these norms. Indeed, despite the exaggerated claims of some men that their wives were so chaste that they had never even come into the presence of males who were not related to them by blood, in real life most women in Athens moved fairly freely about the city and interacted with a range of women and men of different social classes.15 It was only the wealthiest men who could afford to keep their wives secluded within their homes, and even these women played a prominent role in civic cults (section V below). Therefore, despite the ideal of the citizen woman as the virtuous mother of citizen children, whose duties were confined to the household, Athenian women continued to play an important, if mostly informal, role in the life of the community, just as they had before the advent of democracy (Cohen 2000: 30–48; Jameson 1997; Schaps 1998).

Despite this new institutional structure for determining citizenship, in other ways the procedure for determining whether someone was or was not a citizen still relied on the sorts of personal knowledge produced by the rituals of the older fictive kinship groups of the phratry and genos, not to mention the real kinship group of the household (oikos). Although the demes were small enough that “most of the members…must have known each other by sight or by name or both,” in legal disputes over citizenship or inheritance, litigants not only called on fellow demesmen to attest to their parentage but also on their relatives and phratry.16 Older social groupings, then, were not dismantled by the democracy, but co-existed alongside the new structures of the demes, which were themselves built upon the pre-existing village communities of Attica.

Furthermore, the new legal precision and sophistication of the rules for citizenship should not be taken as indicative of the “purity” of the citizenry under the democracy. Despite the much-heralded myths of Athenian “birth from the soil” (autochthony) in Athenian public oratory, the Athenians were far from a closed descent group. Without the bureaucracy and policing power of the modern state (which itself is not particularly successful at preventing illegal immigration), we must imagine that it was not an infrequent occurrence that free non-citizens from other states (metics) and even slaves crossed the legal boundaries and surreptitiously entered the citizen rolls. The periodic attempts to “cleanse” these rolls (diapsēphismos), and the many legal cases in which the status of an individual (citizen, free non-citizen, slave) was in question, suggest that there was much blurring of lines between these groups. Indeed, it was probably only when an individual became embroiled in a legal dispute or was prominent politically, that questions were raised and cases of false citizenship were uncovered.17

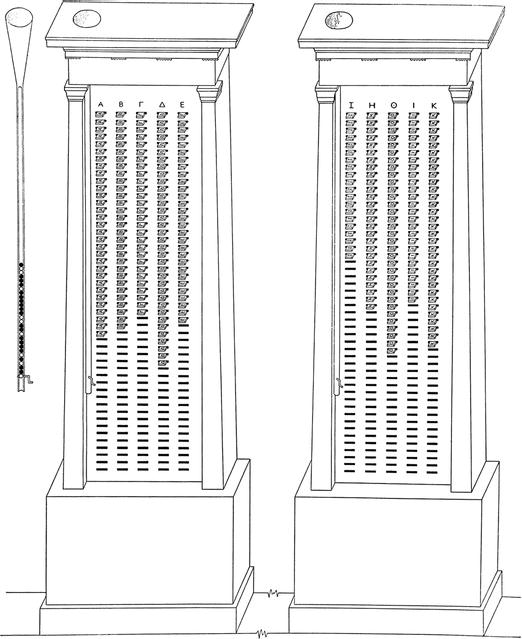

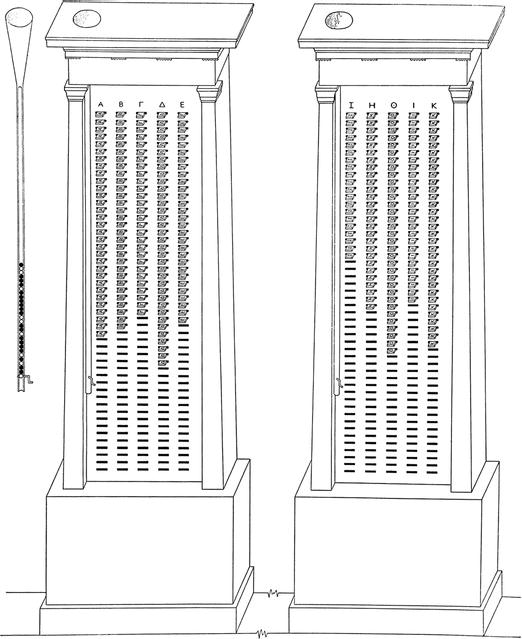

What was truly revolutionary about the democracy was the methods by which it regularly brought together and “mixed up” residents of these deme communities in the newly created tribal divisions (phulai) which were the basis for military, judicial, and political service to the state. The basic mechanism for this “mixing” was the lot, a method of selection that ensured that every Athenian was truly equal, and a practice that became one of the chief symbols of democratic rule. As Aristotle emphasizes, “The following institutions are characteristic of democracy: for all citizens to select the magistrates from all citizens, for all citizens to rule each and each to rule all in turn, selection of all magistrates by lot, or however many magistracies do not require experience or skill” (Politics 1317b19–22; also Herodotus 3.80.2). In Athens, all magistrates, including the members of the Council of 500, were chosen by lot, except for military and a few financial offices which were elective (Ath. Pol. 43.1–2, 61.1). The selection of hundreds of magistrates and jurors was accomplished with the aid of an allotment “machine,” (see Figures 10.1 and 10.2) an example of which was found in the central public place of ancient Athens, the Agora (Boegehold 1995).

Figure 10.1 Drawing of a reconstructed allotment machine (klērotērion). Courtesy of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations.

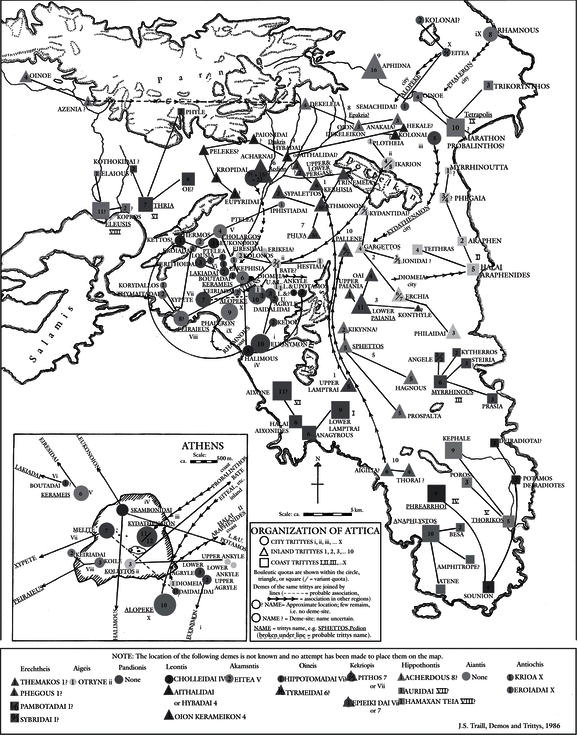

From a modern perspective, the preference for the lot over election seems odd. The ancients believed that election was elitist, since it favored those with high social status due to birth, wealth, or education (Aristotle Politics 1318a1–3); it was only when candidates for public office were chosen randomly that true democracy was achieved. The Athenians therefore used allotment as the mechanism for ensuring that service to the state was performed by a random selection of citizens drawn equally from all regions of Attica (see Figure 10.3). To ensure the equal representation of all regions, ten “tribes” (phulai) were created, each composed of residents of a group of demes from each of three regions of Attica (city, coast and inland; Traill 1975, 1986; Anderson 2003: ch.5).

Figure 10.2 Fragment of an allotment machine (klērotērion). Courtesy of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations.

The use of the lot to appoint magistrates, along with the limitation on terms of office to one year, were the institutional means by which the dominance of any one individual was avoided and the ideal of ruling and being ruled in turn was achieved. As a character in Euripides’ Suppliants responds to a herald who wants to speak to the “tyrant of the land,” so we can imagine an Athenian democrat responding: “This is free city-state and it is not ruled by one man. Rather, the People rules, through yearly rotations in turn…” (404–6).18 Aristotle articulates the same principle more abstractly: “The basis of democracy is freedom. This is what people usually say, as if freedom is only possible in this form of government. For they say that every democracy aims at this. And one part of freedom is to rule and be ruled in turn” (Politics 1117a40–b3).

So far we have established that the advent of democracy both institutionalized and idealized the engagement of citizens in the running of the state on a free and equal basis. But how politically active was the average citizen in reality? How many ordinary citizens attended the assembly? What was the role of elites? How often was a citizen required to hold public office? How much did political activity impinge on everyday life?

Figure 10.3 Political map of Attica by John Traill (1986), from the archives of the Agora Excavations. Courtesy of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations.

Scholars of Athenian democracy working from the institutional perspective, emphasize how the machinery of the democracy required regular and active participation of the majority of Athenian citizens.

Every year the Athenians convened 40 [assembly meetings] and a session was regularly attended by 6,000 citizens; several times a year laws were passed by boards of lawgivers numbering at least 500, and probably 1,000 or more; the council of five hundred met on… ca. 250 days out of 354; on some 150–200 court days thousands of jurors were appointed by lot from a panel of 6,000 citizens aged 30 or more; every year some 700 magistrates…were elected or selected by lot; most were organized in boards of ten; some boards met only rarely but many were active regularly and some even daily; envoys elected by the assembly and sent on a mission to other cities were counted by the score and must, in some years, have exceeded a hundred. To sum up, a majority of the Athenian citizens were frequently, some even regularly, involved in the running of democratic institutions. (Hansen 1989a: 109)

Hansen is here describing the democracy of the second half of the fourth century but, with the exception of the boards of lawgivers (which did not exist in the fifth century), and the number of magistrates (which were if anything more numerous during Athens’ fifth-century empire), his portrait accurately describes the democracy of both the fifth and fourth centuries (see also Mossé, this volume).

Among the various institutions of the Athenian democracy mentioned, perhaps the best example of the need for active participation of ordinary citizens is the Council of 500.19 This Council was established at the time of the founding of the democracy in 508–507 and illustrates key principles of Athenian democracy. First, its membership was drawn by lot from each of the ten tribes, from a list of candidates put forward by the demes (Ath. Pol. 43.2). The number of councillors chosen from each deme was in proportion to the deme population. As we have seen, each of the tribes was composed of residents of demes from three distinct regions of the territory of Athens and therefore consisted of a diverse cross-section of Athenian citizens. The Council drew its membership in equal proportions from each of these internally diverse tribes, and therefore this double process of “mixing up” the population produced a body that was drawn randomly from the whole citizen body from the entire territory of Athens (21.2–4).

Second, a very high percentage of citizens had to serve as council members at some point in their lives, since only those over thirty years of age were eligible to sit on the council (30.2, 31.1), terms were limited to one year, and each citizen could only be chosen twice in his lifetime (62.2). Indeed, Hansen (1999: 249) estimates that about two thirds of all citizens over age forty would have been councilors; therefore ordinary citizens needed to serve if the Council was to be kept at full strength. Furthermore, since the primary job of this Council was to formulate the agenda for the assembly, the ordinary citizens who served in it played a key role in deciding what would be discussed in the assembly. In addition, the fifty members of the Council from each tribe served as a sort of standing executive body for one tenth of the year, and one third of them were on duty twenty-four hours every day. The demands of the state on the ordinary citizen thus seem very steep indeed.

When we turn to the ideals of democratic rule, the picture of a politically engaged citizenry is no less vivid. In his version of Pericles’ speech praising Athenian democracy, Thucydides writes: “It is possible for us to care for both private and public affairs, and even those who must work for a living are not lacking in knowledge of political affairs” (2.40.2). Indeed, in another speech, this time put in the mouth of a politician of the Syracusan democracy, Thucydides notes that ordinary citizens are good judges of public affairs: “the masses, after listening to the arguments, are best at deciding” (6.39). Aristotle explains that the masses together can be better than the few for two reasons: the sum of the knowledge offered by all citizens is greater than that of any individual expert, and, unlike the individual expert, the masses possess diverse kinds of knowledge (Politics 3.1281a40–b10).

Such passages attest to a strong belief in the importance of active decision-making by ordinary citizens in the assembly. In the passage mentioned last, Aristotle even sketches the theoretical basis of this principle by emphasizing that democratic decision-making optimizes the aggregation of knowledge from a diverse citizenry.20 Yet these passages also hint at another truth of Athenian democracy – that ordinary citizens in the assembly often listened to proposals made by elite citizens and then voted. Therein lies a fundamental paradox. The Athenians prized the ideals of the equal right to address the assembly (isēgoria) and free-speech (parrhēsia; Rosen & Sluiter 2004; Saxonhouse 2006). Indeed at each assembly meeting, an invitation was issued to “anyone who wishes” (ho boulomenos) to mount the speaker’s platform and address the assembly. Yet there is significant evidence that a particular group of often well-born and/or wealthy politicians, not ordinary Athenian citizens, gave many of the public speeches in the assembly and therefore played a prominent role in guiding public decision-making.21

Our sources feature a whole string of politicians who enjoyed long-lasting influence with the Athenian people – from Themistocles and Pericles in the fifth century to Demosthenes and Lycurgus in the fourth. These sources are clearly biased towards these prominent individuals – often they report that “many speeches were given” and then focus on those given by one or two influential statesmen – and only speeches of famous speech-writers have survived. Even so, it is undeniable that certain individuals enjoyed unprecedented influence.

This observation forms the crux of a much-debated issue: how are we to reconcile the prominence of certain individuals with the fact that power rested among the people in the assembly? Was there a democracy, or was Athens “in reality the rule of one man,” as Thucydides claims in characterizing Pericles’ ascendancy (2.65)? While few modern scholars accept Thucydides’ extreme assessment of late fifth-century democracy as a monarchy in disguise, some view it as a kind of oligarchy in democratic clothing.22 It is worth emphasizing, though, that, despite the importance of elite leadership, the institutions of democracy required regular active participation by the majority of Athenians, and Athenian texts suggest that the ideal of the politically engaged citizen was based on a clear understanding of the benefits of decision-making by a diverse citizenry.23 Indeed, we are a long way from the aristocratic world of pre-democratic Greece, or contemporary oligarchic states, in which an ordinary citizen like the character Thersites in the Iliad is beaten for daring to criticize the leadership in a public assembly (2.212–270). By contrast, it might even be suggested that under the Athenian democracy it was elite leaders who had to beg for a fair hearing before a mass of highly vocal assembly-goers who did not hesitate to shout down (thorubein) a speaker who said something unpopular. The ordinary farmer in Aristophanes’ comedy Acharnians describes how he will respond to any politician who speaks of anything other than what he wants to hear: “Simply put, I have come prepared to shout, question, and abuse the speakers if they speak about anything other than peace” (37–9). It is clear from other sources that his behavior was typical (Bers 1985). The wealthy politician Demosthenes was so disturbed by heckling in an assembly debate that he interjected: “By the gods! Grant me free speech too, when I speak concerning what is best!” (8.30–2).

Athenian democracy, therefore, required a great deal from her citizens. Did every Athenian participate willingly? Was the obligation to participate oppressive and obstructive to individual freedom and happiness? Did Athenian democracy (by modern or ancient standards) demand an excessively high commitment and sacrifice of individual freedom? There are some hints even in the idealizing speech of Thucydides’ Pericles that not all citizens participated and that those who did not met with social scorn: “We regard the citizen who is inactive in politics not as one who is fond of the quiet life, but as useless” (2.40.2).

Perhaps the best evidence for the potential burdens imposed by compulsory political participation on private citizens was the requirement that wealthy Athenians fund and organize an important civic activity (liturgy; Wilson 2000), such as equipping a warship (the office of the trierarchy), paying for the production of a tragedy or comedy (the office of the chorēgia) or paying for the training and maintenance of a tribal contingent preparing to compete in the athletic competition of the Panathenaia (gymnasiarch). These duties are often portrayed as unduly burdensome on the wealthy, and indeed there is considerable evidence that elites were compelled to put their wealth to work in profit-oriented enterprises (such as raising cash crops or investing in manufacturing or trading enterprises) in order to produce the liquid assets required to undertake these services (Osborne 1991). As an embittered anonymous opponent of democracy (often called the “Old Oligarch”) writes, “The People think that it is right that they earn money by singing, running, dancing, and rowing in the ships, so that they may have [money] and the rich become poorer” (Pseudo-Xenophon Constitution of the Athenians 1.13).

One way of looking at the civic obligations imposed on the rich is that they were simply the institutionalization of a pattern of reciprocity between rich and poor that both predated and postdated the emergence of democracy.24 Indeed, both before and after the democracy, in Greece and in many other pre-modern and modern agricultural societies, communities devised informal and formal mechanisms for the partial redistribution of wealth in an attempt to avoid the outbreak of violent class conflict. In ancient Greece, as in other societies, redistributive mechanisms, such as public feasts and festivals sponsored by the rich, were only partially successful in preventing civil strife. Seen in this light, it is perhaps not too much to say that the remarkable stability of the Athenian democracy was in part due to its successful institutionalization of these redistributive mechanisms. The liturgy system allowed elite families to maintain a private stake in their own economic success, while publicly rewarding them with social capital (“honor”) in return for their use of part of their wealth for public goods. In democratic Athens, as opposed to other contemporary city-states, we hear of no riots of the poor against the rich over land distribution or debts.25 Indeed, the two brief periods of revolution were instigated by the wealthy few, who felt inadequately compensated with political power in return for their services to the state. These tensions were particularly marked during the final phases of the Peloponnesian War (431–404), when the burdens on the wealthy were especially heavy.

As for the ordinary Athenian, there are signs that their participation in public life was also sometimes unwilling. In Aristophanes’ comedy Acharnians, the main character expresses considerable disgust at the tardiness of his fellow citizens as he waits for them to show up for an assembly meeting:

Never before since I first washed as a child

have I felt the sting of my eyes so badly

As I do now, when, at the time of the chief assembly meeting of the month

The meeting grounds are empty early in the morning.

The people are chatting in the market place,

avoiding the purified area of the assembly.

Not even the presiding magistrates have come yet!

Rather, arriving too late, they will push one another

To get the first bench, rushing in all together,

You can be sure! (17–26).

While the theme of lack of enthusiasm for public affairs in this passage may be dismissed as a comic commonplace (and indeed appears in several other comedies), in order for the joke to be funny it must have been an attitude that Athenians recognized in themselves.26

Another possible indication of the less than desirable enthusiasm of ordinary Athenians for public affairs is various new measures that were introduced for compensating citizens for public service. While the nine archons and 500 councillors received a stipend probably from the earliest days of the democracy, new payments were offered for service in the jury courts (from the mid-fifth century) and attendance at the Assembly (c. 403; see Ath. Pol. 41.3, 62.2, 69.2; Aristoph. Ecclesiazusae 289–311, 392). The amount of these payments (between three and nine obols: the average daily wage for an unskilled laborer) suggests that they were designed to encourage attendance especially by working class citizens who would need some financial compensation for lost working time. In Aristophanes’ Wasps, the prospect of jury pay entices those infirm or elderly citizens who, being past their prime, could not earn their livelihood through wage labor. While we should not accept this comic portrait wholesale, it does suggest that financial compensation may have increased public service, and that such service would have been particularly attractive to those in the lower income brackets.

Payments for public service are one area in which we see that the empire may have facilitated democracy. It is perhaps not coincidental that jury pay was introduced around the same time that the Delian League treasury was moved from Delos to Athens in 454. Yet assembly pay was introduced only in 403 after the fall of the empire, and payments for political service continued through the fourth century. Xenophon, however, in On Revenues, written in 355–354, is much concerned with how the Athenian masses can acquire public support (trophē) without oppressing other Greeks (1.1, 4.49–6.3). He proposes a series of measures designed to increase economic activity in Attica, mainly through the exploitation of the silver mines and the encouragement of commerce and trade. Xenophon attests, therefore, both to the difficulty of providing sufficient public support for Athenians without imperial revenues, and the need to find alternative sources of public funds at a time when the imposition of tribute on other Greeks was no longer feasible. Both these pieces of evidence suggest that the empire had a stimulative effect on the democracy, and this relationship probably worked in both directions. Thucydides certainly suggests as much in his vivid depiction of the decision of the Athenians to launch the Sicilian expedition (6.1–32). As he attests, the Athenians were motivated to attack Sicily not least because it raised the prospect of securing a stipend for military service for the foreseeable future (6.24.3). Indeed, the empire began through the mutually beneficial exchange of allied money for Athenian military protection and the connection between pay for rowing in the navy and support for democracy probably only grew tighter as Athens increased in power.

Of course, ordinary Athenians were not only encouraged through financial incentives to row in the fleet and participate in the courts and the assembly but could also be selected by lot to serve on the Council or in one of the many other offices responsible for administering the affairs of Athens and her empire. In contrast to the liturgies performed by rich citizens, public offices such as the archonship were often filled by ordinary Athenians who brought no special skills or resources to their positions. In a court speech (Ps.-Demosthenes 59.72), for example, we hear of an ordinary Athenian “of noble birth but poor and inexperienced in public affairs” who was chosen by lot to be the chief magistrate (archon basileus) and, as a consequence, had the responsibility to oversee important collective activities such as the organization of public festivals and sacrifices. How could an ordinary Athenian serving for his first and only time in this position master such major tasks? One answer is that the citizen selected by lot to fill one of these posts could choose some “assessors” (paredroi) to assist him (Ath. Pol. 56.1; MacDowell 1990: 395; Kapparis 1999: 322), and therefore could draw on individuals with more experience than he himself might possess. In several cases, we see that relatives perform this function, which illustrates the blending of democratic institutions with other kinds of social ties.

The blending of institutions with pre-existing social ties brings up the important topic of the family. Was the private life of the family changed under the democracy? As we have seen, the institutions of the democracy required a greater engagement in the political management of the community by individual citizens than ever before or (probably) since. On the other hand, the availability of pay for political activity meant that not all time spent on politics was a loss to private interests. Even the wealthy elite, who were required to devote a portion of their private resources (time and money) for the public good, were compensated by the increased social standing that they received for such services.

The role of public speech in compensating individuals for their sacrifices to the state is a vital aspect of Athenian democracy since it was the key to convincing both wealthy and ordinary citizens to devote themselves to the common good. In brief, public speech functioned to generate social capital in exchange for service to the state in terms of actual physical labor (rowing in the fleet, serving as a hoplite), leadership (offering advice to the people in the assembly), in administrative and organizational capacities (serving as a magistrate), or through financial contributions (liturgies). It is here that the work of scholars of Athenian ideals such as Nicole Loraux and Josiah Ober have contributed significantly to our understanding of the Athenian democracy. These scholars argue that the key to the success of this democracy was its ability to create occasions for the public negotiation and expression of democratic ideals to which both elites and masses could subscribe. While other city-states certainly also held public events in which civic ideals were articulated, these tended to be one-way communications in which there was very little room for input from the mass of listening citizens.27 What was unique about Athens is that there were multiple and overlapping occasions for contesting and shaping the ideal of the citizen in public speech. Furthermore, these occasions allowed for a mutual give and take between elite speaker and mass audience that resulted in the honing of a delicate balance between, for example, private and public good, the rule of law versus social equity, and the interests of the few versus those of the many.

The principal forum for the articulation of democratic ideals was of course the assembly. It was complemented by the courts where elite litigants presented themselves before mass juries of ordinary citizens.28 In this latter context, we find that elite speakers made an inordinate effort to portray themselves as good citizens and vilify their opponents as bad citizens, regardless of the legal issue at stake.29 For example, in his legal battle with Meidias, Demosthenes spends a great deal of his prosecution speech describing how he himself had performed the liturgies required of a wealthy citizen, while his opponent had not: “This man,… although he is about fifty years old,.. has performed no more liturgies than I have, though I am only thirty-two years old… I have feasted my tribe and served as chorus-producer at the Panathenaia. He has done neither of these things” (21.154–6).

Demosthenes then explains how the jurors should look upon those who spend their wealth for private enjoyment, as opposed to those who devote themselves to the public good: “I don’t know what benefit the majority of you derive when Meidias acquires possessions for the sake of private luxury and advantage… You should not honor or admire such things, nor should you judge a man honorable if he builds a fancy house or has acquired many maidservants or beautiful furniture. Rather, you should grant distinction and honor to a man for his contributions to things in which the majority of you have a share” (21.159). Demosthenes here both appeals to the beliefs of the mass of ordinary Athenians in the jury and shapes their collective beliefs in accordance with his own interest in the present case. It is precisely through this two-way communication between speakers and audiences in thousands of assembly meetings and court cases, that democratic ideals were constantly shaped and reshaped in ways that ultimately optimized the benefit for all Athenian citizens.

A third vital context for the negotiation of democratic ideals was the speech given over the war dead in a public funeral held annually in Athens (Loraux 1986). We have already seen how, according to Thucydides, Pericles used this occasion in 430 to articulate to the Athenians the value of democracy and the reasons why it was worth dying for. Several other funeral speeches survive and each case illustrates how the ideal of the citizen was constructed in ways that not only encouraged citizens to subordinate their private interests to the public good, but explained to them how public and private interest could be best balanced under a free and democratic system of rule. One speech praising the men who died fighting Philip of Macedon at Chaironeia, for example, reminds the Athenians of the many benefits offered by democracy. In particular, these include freedom of speech and the confidence that one’s fellow citizens will fight for the collective interest rather than shirk their duty, as the subjects of autocratic regimes tend to do.

These men were of such a sort… not least because of their system of government (politeia). For autocratic regimes controlled by the few produce fear in their citizens but no sense of shame. Whenever the contest of war approaches, everyone quickly saves himself, knowing that… even if he behaves in the most unseemly way, little shame will ensue for him in the rest of his life. But democracies possess many other noble and just things to which the right thinking man should hold fast, not least of all, it is impossible to deter free speech (parrhēsia), which derives from the truth… For neither is it possible for those doing shameful acts to eliminate everyone, so that even a single individual, uttering a truthful reproach, causes pain [to the wrongdoer]… Out of fear of shame, these men all rightly stood their ground against the danger approaching from their opponents, and they preferred a noble death to a shameful life. (Ps.-Demosthenes 60.25)

The idea that men fight more courageously under a democracy than under autocracy seems to have been a central tenet of Athenian democratic theory (Forsdyke 2001, 2002). The essential idea is that under a democracy men fight more bravely because they have a stake in the outcome of the battle whereas under autocratic regimes men shirk their duty because the benefits of victory go primarily to a small group of leaders (Herodotus 5.78).30 Remarkably, these beliefs are formulated in Athenian public speech by emphasizing largely non-material benefits: citizens of a democracy reap their rewards in terms of freedom (both positive and negative), justice, and equality.

In the final part of this chapter, I turn to the ways in which democracy had an impact on the community’s social and cultural life. As noted at the beginning, the advent of democracy corresponded with an upsurge in the ritual life of the community, particularly in the number of public festivals. The connection between democracy and festival life is expressed again in Pericles’ funeral oration. Immediately after outlining the characteristics of democracy, he states: “And furthermore, we have provided the most relaxations from toils for our spirit, participating in festival games and sacrifices lasting throughout the year…” (2.38; cf. Ps.-Xenophon Ath. Pol. 3.2; Aristophanes Clouds 307; Ps.-Plato Alcibiades 148e). This is no idle boast (Osborne 1993a; Fisher 1998, 2011). Indeed, Fisher (2011; also Wilson 2003) points out that “[t]he ten Cleisthenic tribes were not only central to the organization and running of the political and military systems; they played major roles in providing annually teams of thousands of male athletic competitors, and dithyrambic and dramatic chorus men, of differing age-classes, in a greatly increased number of polis festivals.” At the Panathenaic festival, for example, competitions were introduced featuring tribally based teams of adult males, ephebes (young men in military training), and boys in competitions such as the torch race (lampadēphoroi), the “tribal contest in manly excellence,” a mock cavalry battle (anthippasia), and a boat race.31 At the Dionysia, choruses of citizens sang and danced in tragedies and comedies before the ten judges who were drawn from each of the tribes and cast their votes in accordance with the reactions of the audience.

Again, while other city-states also had a rich ritual life, the Athenian democracy appears to have been particularly successful at harnessing the cohesion-enhancing effects of communal festivity, and in linking this unity to the institutions and ideals of democracy.32 In particular, the tribal basis of many of the competitive events not only brought festival participation in parallel with bouleutic and military service, but also united elites and masses together “in the common concern for victory” (Fisher 2011). In festival life, just as in political life, upper class citizens cooperated with ordinary Athenians in ways that brought together elite financial resources and organizational talents with non-elite manpower. We can imagine that the festive atmosphere and the excitement of the competition would have amplified the cohesive effects of these rituals. In this way, the musical, athletic, and dramatic competitions represented and strengthened the democracy as much as did political and military activity.

Of course, festivals such as the Panathenaia and the Dionysia long predated the democracy, and not all of the earlier, more hierarchical, practices were elided. For example, the grand procession to the acropolis that opened the festivities of the Panathenaia not only featured women from certain elite families in privileged positions, but included a broader portion of the population than just adult citizen men.33 Women, metics, and citizen men marched together in this parade, and were given different roles according to their status. Similarly, in the feasts that followed the sacrifice, the meat was divided both hierarchically (between important cult functionaries and dignitaries from the procession) and democratically (among the Athenians as a whole on the basis of their tribal and deme groups).34 Most strikingly of all, individual competitions continued alongside tribal ones in events that had been traditionally the preserve of leisured elites.

One measure, however, of the expanded role of ordinary Athenians in festival competitions is the evidence for the construction of new public sports facilities. As Donald Kyle observes (1992: 81), “Athens was exceptional in having three major public gymnasia, the Academy, Lyceum and Kynosarges… [along with] many smaller palaestrae (wrestling schools).” Not everyone in Athens was happy with this development. A conservative character in Aristophanes’ Clouds complains that standards of fitness have declined considerably (988–9). Similarly, the Old Oligarch grumbles, “the wealthy have gymnasia and baths and changing facilities at their private expense, but People build for themselves exclusively many wrestling grounds, changing rooms and public baths. And the mob gets more benefit from these than the few and the wealthy” (Ps.-Xenophon, Ath. Pol. 2.10). This evidence suggests that ordinary Athenians were training for individual as well as team events at the festivals (Fisher 1998).35 Furthermore, since athletic facilities were once the preserve of a leisured elite, the expansion of festival competitions under the democracy had a visible impact on the physical appearance of the city.

This brings up a fruitful avenue for understanding the impact of democracy on communal life, namely the ways that the democracy shaped civic space. What was it like to move about the city under the democracy and how might it have differed from life in a non-democratic city?

In addressing these questions, it is important to recognize that much of the built environment of Classical Athens was not the product of democracy per se, but at most a secondary effect of the success of the democracy.36 When Pericles called on the Athenians to admire the beauty of the city, much of that civic glamor was a result of Athens’ empire, not her constitution. Most obviously, the buildings of the acropolis – the temple of Athena Parthenos, the gold and ivory cult statue and the monumental entranceway to this sacred complex, the Propylaea – were all built from the proceeds of empire (Plutarch, Pericles 12).37 The purpose of these buildings, namely to facilitate (albeit now on a grander scale than ever before) proper collective worship of the gods, was an important aspect of Athenian, indeed Greek culture, long before the emergence of democracy. Yet some scholars argue that, just as the rituals of worship were to some extent democratized in classical Athens, so was the artistic program of these monuments. For example, the Parthenon frieze representing the Panathenaic procession may reflect democratic values in the way that it depicts individualized cavalrymen all working towards a common end (Osborne 1994; cf. Neils 1992; Blok 2007). In the same frieze, however, certain groups are marked off from others in the procession, and certain elite characteristics (such as cavalry service or cultic authority) are privileged (Brulé 1987, 1996; Wohl 1996; Maurizio 1998). The most we can say, therefore, is that democratic themes are embedded in cultural forms and ideals that derive from a non-democratic past.

Yet there were buildings and monuments that were explicitly connected with democracy. First of all, a new monumental Council House was built for the democratic Council of 500 soon after 508/7. This building was erected in the Agora – a newly cleared open public space to the northwest of the acropolis that seems to have replaced an earlier central public space to the southeast. Indeed, it was under the democracy that the area to the northwest became the main civic center of Athens (Shear 1994; Papadopoulos 1996). It was here that the archon basileus (above) had his offices. In addition to the daily meetings of the Council in the Council House, the fifty councilors who were on duty (prytaneis) took their meals in a circular building (Tholos) located next to the Council House (Ath. Pol. 43.2–3). Furthermore, the democratic courts met in the Agora, the public archives were kept here, and citizens came here to see notices of public business posted on the monument of the eponymous heroes of the ten tribes (see Figure 10.6, below).

The Agora was the commercial as well as the political and legal center of the city (Millett 1998), and therefore these public buildings stood side by side with fish stalls, blacksmiths and barber shops. The bustle of the Agora is comically parodied by the fourth-century poet Eubulus who writes that “In that place [the Agora] everything will be for sale all together: figs, summoners, bunches of grapes, turnips, apples, witnesses, roses, medlar-trees, sausages, honeycomb, chickpeas, lawsuits, beestings, beestings-pudding, myrtle berries, allotment machines, hyacinths, lambs, waterclocks, laws, indictments ….” (fr.74 Kassel-Austin). It was to the Agora that citizens came for news, gossip, and information, and it was here that not just formal politics of the law courts and the magistrates took place, but much of what we might call informal or “everyday politics.”38 It was here that politicians such as Demosthenes harangued the people in advance of the formal assembly meetings (Aeschines 2.86; Dinarchus 1.32; Vlassopoulos 2007b: 40). It was here that social offenders – adulterers, thieves, and parent-beaters – were put on display for public ridicule (Forsdyke 2008).

Most importantly, the Agora was a space where citizens, non-citizens, slaves, and women came together for a wide variety of public and private matters. We have seen that festivals were an occasion when legal and ideological divisions between citizen and non-citizen, male and female, and free and slave were not strictly observed. The public spaces of the city, and above all the Agora, were another context in which legal and social distinctions were blurred. It is in this aspect of public life – the interaction of all classes, genders, and statuses in the Agora – that we can recognize the ways that politics under the democracy – despite the creation of formal institutions and legal restrictions on citizenship – continued in a pattern that had begun long before, and would continue long after, the existence of democracy. Just as women, metics, and slaves might overhear Demosthenes “haranguing the people” in the Agora, so they might be members of the crowd that stood outside the fences surrounding the Council House (Herodotus 9.5.2; Forsdyke 2008), the courtrooms (Lanni 1997), and the political assembly (below). While these bystanders could not vote, we know that they made their opinions known by shouting (Bers 1985) and at times even acting violently in response to debate (Herodotus 5.9; Forsdyke 2008).

Another important civic space for the democracy was the Pnyx, the area where the political assembly met (Hansen 1989a: 129–41, 143–53).39 This area seems to have been purpose-built under the democracy for the assembly of male citizens, replacing a more informal gathering place in the (old) Agora in the Archaic period. It was carved out of a rocky outcrop and equipped with a speaker’s platform, a retaining wall, as well as temporary wicker fences that enclosed the area for approximately 6,000 attendees (ibid.). Once again, however, this space was not the exclusive preserve of male citizens. We hear of the fences being removed after voting was completed, after which foreigners were allowed to enter and view the proceedings (Demosthenes18.169; Ps.-Demosthenes 59.89; Hansen, ibid.).

If we turn to the many public monuments and statues set up by the democracy in the public spaces of the city, we see that many of its most important symbols and ideals were openly available to be “consumed” by women, non-citizens, and slaves as much as the male citizens themselves. One might even propose that it was these “publications” of democratic ideals in the public space, as much as the daily interaction of citizens, metics, and slaves in the fields, the workshops, and on campaign, that led to a diffusion of democratic culture among these groups.40

Perhaps the foremost monument of the democracy was the statue of the tyrannicides.41 (See Figure 10.4). This statue group celebrated the killing of Hipparchus, the son of the tyrant Peisistratus, by two citizens, Harmodius and Aristogeiton, in 514. As Thucydides is at pains to make clear (1.20; 6.54–9; cf. Herodotus 5.55–65), this murder did not end the tyranny, since Hipparchus’s older brother Hippias continued to rule as tyrant until 510 when the tyranny was overthrown by some Athenian exiles with Spartan help. Nevertheless, the tyrannicides were remembered by the Athenians as responsible for the end of the tyranny and the introduction of democracy.42 Their statues in a dramatic tyrant-slaying pose were erected in the Agora in the late sixth or early fifth century, and, when these were stolen by the Persian King Xerxes in 480, they were replaced by new ones.

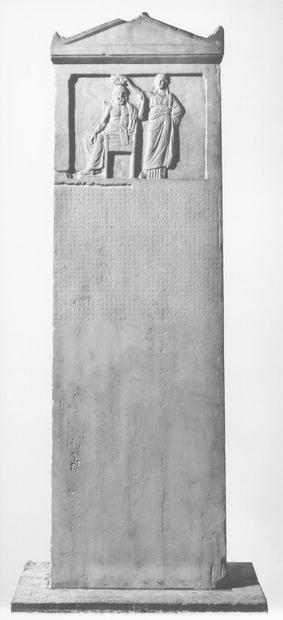

The message of this monument – the evils of tyranny and the heroic act of its overthrow – was replicated and reinforced by several other monuments in the city. Thucydides mentions a public inscription on the Acropolis commemorating the “injustice of the tyrants,” and the fourth century politician Lycurgus reminds his audience of a bronze inscription – apparently made from a statue of a descendant of the tyrant that the People removed from the acropolis and had melted down – recording the names of sinners and traitors (Thucydides 6.55; Lycurgus Against Leocrates 117–19). Perhaps the most impressive example of this commemoration of tyranny is the inscription on a stele erected by an assembly decree that was proposed by one Demophantos after the suppression of the oligarchic revolution in 411–410 (Andocides 1.96–8; Demosthenes 20.159; Lycurgus Leocrates 124–7). This decree was located outside the Council House in the Agora, in sight of the tyrannicide statue group itself. We do not know what the monument on which the decree of Demophantos was inscribed looked like, but a later, fourth-century anti-tyranny decree featured a relief of Demos being crowned by Demokratia.43 (See Figure 10.5).

Figure 10.4 The Tyrannicides. Second-century Roman copy of the mid-fifth century BCE Greek sculptural group. Photo Credit: Alfredo Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY.

Figure 10.5 Athenian Anti-Tyranny Law (Law of Eukrates), 337/6 BCE. Courtesy of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations.

The text of the decree of Demophantos encouraged viewers (citizen and non-citizen alike) to take individual action in defense of democracy by promising them immunity if they killed anyone responsible for overthrowing the democracy, holding office after the democracy was overthrown, or setting himself up as a tyrant or helping set up a tyrant (Ober [n.41]; Shear 2007). Remarkably, the decree required the Athenians to swear an oath, collectively, by tribe and by deme. The collective act of swearing an oath “to kill by word, deed, and vote, and by my own hand in so far as I am able whoever overthrows the democracy” reinforced the Athenian identity as democrats and made defense of the democracy not just a civic but a divinely ordained duty.44 Each time an Athenian passed the monument in the Agora, he would be reminded of his oath and his obligation to the state and the gods to uphold the democracy. Although non-citizens, women, and slaves were not among the initial oath-swearers, they too experienced these monuments as part of the civic landscape. Can we deny that they too might be influenced by the messages about tyranny and democracy?

Figure 10.6 Reconstruction of the Monument of the Eponymous Heroes. Courtesy of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations.

A second major monument in the Agora connected with democracy was the statue group of the eponymous heroes.45 (See Figure 10.6).

As already mentioned, this monument served as a public noticeboard, and members of each of the ten tribes could find announcements posted under the statue of their tribal hero. Besides the visual symbolism of the statues reflecting the key divisions of the population under the democracy, the monument served as a focal point for ritual worship of the heroes by Athenians in their tribal units.46 The heroes themselves were also the source of oral traditions in which civic virtues – especially the willingness to sacrifice private interests for the public good – were articulated.47 For example, the hero Erechtheus is commemorated in a funeral oration as having sacrificed his own children in order to save the land of Attica, just as his tribesmen made similar personal sacrifices for the state. Similarly, Theseus is credited with the introduction of the equal right to speak (isēgoria), one of the key terms for democracy (Herodotus 5.78), and his tribesmen are praised for being willing to die before seeing the democracy overthrown (Ps.-Demosthenes 60.27).

Interestingly, the wives and daughters of the tribal heroes are commemorated for their sacrifices to the public good as much as the male heroes themselves. The daughters of the tribal hero Leo offered an inspiring example: “The tribesmen of Leo had heard that the legendary daughters of Leo had given themselves up to the citizens as a sacrifice on behalf of the land. When those women displayed such manly courage, they thought it was not lawful for them to appear to be worse men than those women” (Ps.-Demosthenes 60.29).48 Once again, women, though denied a formal role, figure prominently in the vitally important social imaginary of the democracy.

Finally, if we turn now from major monuments to the hundreds of publicly displayed laws and decrees, we can see that the Athenians were inundated with the written word. Relative to other city-states, the Athenians were so active in publishing their laws and decrees that scholars have wondered whether the public display of laws and decrees was a distinctive feature of democracy.49 While it is true that non-democratic states made use of writing and that there is no deterministic relation between democracy and the use of writing, the ideals of democracy “no doubt played an important part in motivating the Athenians to inscribe their texts” (Hedrick 1999: 388).50 As Charles Hedrick puts it, “the connotations of Athenian state inscriptions were surely democratic. Athens was (at the least nominally) a democracy. Therefore, to the extent that official writing in Athens was associated with the state, ipso facto it had democratic connotations” (ibid.). Most strikingly, several inscriptions explicitly state that they are being erected for “anyone who desires to inspect [the law or decree]” (skopein tōi boulomenōi).51 In other words, the Athenians understood that the goal of publication of laws and decrees was to keep the citizens informed. Given the importance of information to democratic rule, there is a clear connection between the publication of decrees and the ideals of democracy.52

To move about the city of Athens was to encounter visible reminders of the institutions and ideals of democracy. Typically, a law or decree began with the formula “it seemed to the People that…” (tōi dēmōi edokei), or “it seemed to the Council that” (tēi boulēi edokei), thus reminding the viewer of the fact that power rested with the people, or the subsection of the people who sat on the Council at the time the decree was passed. Most of these inscriptions were erected on the Acropolis, the ancient “heart” of the city (Liddel 2003). It is likely that the religious nature of the Acropolis gave additional divine authority to the public decrees erected there. Yet the Agora, as the democratic center of the city, was also a significant site for the erection of inscriptions. We have already mentioned the Decree of Demophantos outside the Council House. Equally significant was the reorganization of the laws in 410–399, the results of which were displayed on purpose-built walls surrounding the courtyard of the offices of the archon basileus (Shear 2007: 160). Once again, women, non-citizens, and slaves might be viewers of these public articulations of the power of the people and the principles of freedom, equality, and justice entailed therein.

Summing up this rapid overview of the multiple ways in which the democracy influenced communal life, one might resort to the French saying, “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.” In many respects, the democracy radically altered the scope and nature of political participation in the community. In others – for example, in the sphere of ritual and religion – the democracy made only a faint impression on what were robust institutions and ideals that long predated the advent of democracy. The key to understanding the Athenian democracy, I suggest, is to appreciate the ways that tradition and innovation combined in complex ways to produce a hybrid society in which the new did not wholly dispel the old. Finally, I suggest it is vital to recognize that the existence of highly sophisticated formal institutions did not preclude the informal participation of women, metics, and slaves in the life of the community and the propagation of its ideals.

CQ | Classical Quarterly |

FGrHist | Jacoby 1923–98 |

GRBS | Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies |

IG | Inscriptiones Graecae |

JHS | Journal of Hellenic Studies |

RO | Rhodes and Osborne 2003 |

SEG | Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum |

Notes

1 All translations are my own. All dates are BCE.

2 See the articles collected in Hansen 1983a, 1989a (esp. 263–9), and his magisterial overview of 1999; Rhodes 1972, 1981 (the indispensable commentary on the Aristotelian Constitution of the Athenians [henceforth Ath. Pol.). Other important institutional studies are Traill 1975, 1986; Whitehead 1986; Develin 1989; Lambert 1993. For the development of the democracy over time, see n.10 below.

3 Loraux 1986; Ober 1989, 1996. Ober’s recent work (2008), however, has focused more on the institutions of democracy.

4 On the number of Athenian festivals compared to other states, see section V below. On the artistic and intellectual efflorescence under the democracy see, for example, Winkler & Zeitlin 1990; Boedeker & Raaflaub 1998; Goldhill & Osborne 1999, 2006.

5 The work of Loraux (e.g., 1981, 1989, 1996 and 2003) and Zeitlin (e.g., 1996) stands out here. See also Hunter 1994; Humphreys 1993; Pomeroy 1997; Cox 1998; Patterson 1998; Lardinois & McClure 2001; O’Higgins 2003; Blok 2005; Lefkowitz 1996; Connelly 2007.

6 Whitehead 1977; Finley 1980, 1981; Garlan 1988; Hunt 1998; Hunter 1994; Hunter & Edmondson 2000; Cohen 1992, 2000; Zelnick-Abramovitz 2005.

7 See, e.g., Cohen 1992, 2000; Jones 1999; Hunter & Edmondson 2000, and, more recently, Vlassopoulos 2007b, 2009; Forsdyke 2012.

8 Jameson 1997 and Vlassopoulos 2009 make a similar argument.

9 The power of the people in assembly as the primary attribute of democracy: e.g., Aeschylus Suppliants 600–8; Herodotus 3.80.6; Aristotle Politics 1317b29; Ath. Pol. 41.2: “The People has made itself in control over everything, and it manages public affairs through public decrees of the assembly and through the courts in which the People are in control.”

10 Ath. Pol. 41 sketches the steps by which the people gained power and transformed the state into a democracy, placing the beginning of democracy at the time of Solon (9–10) and dating its fully developed state only after 403. Modern scholars suggest various dates, depending in part on how they define democracy (see also Raaflaub, this vol.): Morris (1996) backdates democratic values to the eighth century; Wallace (in Raaflaub et al. 2007: 49–82) proposes the time of Solon, Ober (ibid. 83–104) that of Cleisthenes, Raaflaub (ibid. 105–54) the mid-fifth century, and Hansen (1999) the late fifth and fourth centuries as the period in which Athenian institutional structures were fully developed. For discussion of the significance, in this context, of the revision of the laws in 410–399 and the creation of a new board of lawgivers (nomothetae), see Ostwald 1986; Ober 1989: 95–103; Eder 1995, 1998; Hansen 1999, 2010. For the purposes of this chapter, I treat the period from 508–507–322 as a unit (see also Rhodes 1980; Bleicken 1987; 1994: 61–6), though I will note certain important developments as are relevant to my discussion.

11 On ancient Greek concepts of freedom in general, see Raaflaub 2004; Hansen 1989b, 1996.

12 The regularization of meetings and agenda may have been prompted by the massive increase in business and decision-making caused by the acquisition of empire after 479 (Schuller 1984).

13 The number of deme meetings per year is unknown, and there was probably some variation between demes: Whitehead 1986: 90–2. Demes as replicating procedures of polis: votes were taken by show of hands (cheirotonia) or by ballot (ps ē phisma; Demosthenes 57.13), and deme officials were subject to scrutiny (euthun ē) at the end of their term of office (RO 63; Whitehead, 92–6). On the role of the demes in Cleisthenes’ reforms, see Traill 1975, 1986; Anderson 2003.

14 The requirement that citizens had to prove that both parents were citizens is known as Pericles’ Citizenship Law; for recent discussion, sources, and bibliography, see Patterson 2005.

15 Cohen 1991 discusses the ideal of seclusion and demonstrates, by way of comparative anthropology, the ways that women in practice contravened this ideal. That many women needed to work outside the house, in the fields, in the marketplace, in services and crafts, is shown by Brock 1994; Scheidel 1995–6. See also Schaps 1979 and 1998.

16 The deme as a “face-to-face society”: Whitehead 1986: 226. On the continuing role of the phratry, genos and oikos as source of validation of citizen status: e.g., Dem. 57.19, 20–4, 40; 59.59.

17 On the myth of autochthony and Athenian public oratory, see Loraux 1981, 1986, 1996; Shapiro 1998. Purges of the citizen rolls: Ath. Pol. 13.5 (c. 510); Philochorus FGrHist 328 F119; Plutarch Pericles 37.2, 4 (445/6); Aeschines 1.86 (346/5). Legal disputes raising issues of citizenship: e.g., Lysias 4, 16, 23; Demosthenes 21.149 ff.; 57, 59; Aeschines 1. Demosthenes (18.129–30; 19.249) and Aeschines (2.78–9; 3.172) in their famous feuds accused one another of having less than respectable credentials as citizens. Blurring of lines between legal statuses: Cohen 2000: 76–7, 108–12; Hunter and Edmondson 2000; Vlassopoulos 2007a, 2007b, 2009; Forsdyke 2012.

18 For democratic ideology in Athenian tragedy, see Raaflaub 1989; Goldhill 1990; Forsdyke 2001.

19 This Council probably replaced an earlier Council of 400 (Ath. Pol. 8.4, 21.3; Plutarch Solon 19.1 with Rhodes 1972: 208–9).

20 Ober 2008 argues that institutionally Athenian democracy was designed to optimize knowledge aggregation of a diverse citizenry.

21 On Athenian politicians (rh ē tores), see Hansen 1983a, 1989a: 1–24, 25–72, 93–127; 1999: 266–74. Although originally these men belonged to a few established families of wealth and property, by the second half of the fifth century a more diverse group, including men whose wealth was recently acquired through manufacturing and other enterprises, emerged as leaders; see Connor 1971; Mossé 1995: 131–53.

22 For example, Samons 2004. Ober (1989) and Hansen (1999) agree that while democracy relied to some extent on the advice of wealthy individuals who had the education and leisure to study the issues, the fact that decisions rested ultimately with the people as a whole is decisive evidence that there was a genuine democracy.

23 Hansen 1989a: 93–127 emphasizes that despite the overrepresentation of some political leaders in the record of proposers of decrees, the large number of proposers shows that ordinary citizens were active in this regard.

24 For detailed discussion of the claims in this paragraph, see Forsdyke 2005, 2006, 2008, 2012.

25 For civil war resulting from debts and land issues, see, e.g., Thucydides 3.70, 81 (Corcyra); 8.21 (Samos). For discussion and further examples, see de St. Croix 1981; Lintott 1982; Fuks 1984; Gehrke 1985; Forsdyke 2012.

26 In the mundus inversus of Aristophanes Lysistrata 1–65 it is the women who are late for assembly.

27 For example, at Sparta, the patriotic poems of Tyrtaeus encouraged courageous self-sacrifice of hoplite soldiers for the good of the community, as would the tales of virtuous actions recounted over meals in the messes. The emphasis on obedience to authority in Sparta, however, precluded any public negotiation of the balance between individual and collective good.

28 On the assembly and law courts as contexts for symbolic interaction of mass and elites through public speech, see above all Ober 1989. For an overview of the Athenian court system, see Carey 1997: 1–19.

29 Lanni 2006 argues that the Athenians deliberately chose to favor social equity over the strict application of the law and that this decision explains the emphasis placed in extant speeches on the litigants’ performance of civic duties; see also Lanni, this volume.

30 Of course there was a gap between this ideal and reality (Christ 2006). In reality, there were draft-dodgers, and not every one stood their ground in battle.

31 Neils 1992: 15–17. Boegehold 1996 suggests that the contest in manly excellence (euandria) was a group (choral) song and dance competition.

32 On democracy and religion, see recently Jameson 1998; Boedeker 2007, and Osborne, this volume.

33 For the women who marched in the procession carrying ritual baskets (kan ē phoroi), see, e.g., Thucydides 6.56.1; Aristophanes Lysistrata 641–7. For the variety of important roles played by women in civic festivals, see Lefkowitz 1996; Cohen 2000: 46–8; Parker 2005: 218–52 and passim; Connelly 2007. As Cohen observes, women are “attested as priestesses in more than forty public cults, as holders of many additional subsacerdotal positions, as performers of ritual roles, and as members of choruses.” In Parker’s words, women held a “kind of ‘cultic citizenship’” (1996: 80). Osborne 1993b shows convincingly that women were not excluded from the division of sacrificial meat.

34 RO 81 = IG II2 334 with Schmitt-Pantel 1992: 126–30; Parker 2005: 266–9.

35 Kurt Raaflaub reminds me that these facilities were perhaps also used for training for war.

36 The essays in Boedeker & Raaflaub 1998 explore the “complex interplay between democracy, empire, and the arts” (337). See especially Hölscher 1996, 1998; also Raaflaub 2001.

37 For a summary of the debate about Plutarch’s claim that Pericles used imperial tribute for the construction of temples, and some reasons for accepting this claim, see Kallet 1998: 49.

38 On news, information, and gossip in the Agora, see Cohen 1991: 133–70; Hunter 1994: 96–119; Lewis 1996.

39 The Pnyx was re-oriented in the late fifth or early fourth century, possibly in order to regulate attendance more strictly following the introduction of pay for assembly-attendance (Hansen 1989a: 143–54).

40 For citizens and slaves working side-by-side in the fields, see Jameson 1977, 2001; Cartledge 2002; in manufacturing: Osborne 1995; Harris 2002; in the army and fleet: Hunt 1998.

41 For full discussion of these monuments, see the chapters by Raaflaub and Ober in Morgan 2003: 59–93, 215–50; Shear 2007.

42 See, e.g., the drinking songs preserved in Athenaeus 15.695a = Carmina convivalia 893–6 Page.

43 The Law of Eukrates of 337–336 (RO 79, with Plate 7).

44 One might add to this list of democratic monuments the decree honoring those who fought against the oligarchs to restore the democracy in 403: SEG 28 no.45; Aeschines 3.187, 190–1. Thucydides’ account (8.92) of the killing of Phrynichos in 411 in the agora in broad daylight by one of the watchmen is perhaps an example of this sort of extrajudicial killing of a potential tyrant, albeit before the passage of the decree of Demophantos. Phrynichus was posthumously convicted, his murderer later publicly honored (Bleckmann 1998: 379–86).

45 On the monument, see Aristophanes Peace 1183–4; Ath. Pol. 53.4. The original statues date to the fifth century, although the surviving base of the monument dates to c. 330. See Camp 2001: 157–8.

46 On hero cult in general, see Hägg 1999. On Athenian tribal heroes, Kron 1976; Kearns 1989.

47 Ps.-Demosthenes 60.27–31 recalls the myths of each of the ten tribal heroes.

48 Other women mentioned in the catalog of tribal heroes: Procne and Philomene, daughters of Pandion; Aethra, mother of Acamas; Semele, mother of Oeneus; Alope, mother of Hippothoön.

49 Hedrick 1999 with references to previous scholarship and graphs depicting the chronological distribution of surviving inscriptions. Hedrick estimates the total number of Athenian inscriptions to be “in the region of 20,000” (390) against a total of about 100,000 Greek inscriptions. For discussion, see also Meyer, this volume.

50 For a recent discussion of the variety of uses of public writing in the Greek city-states, with particular attention to the case of Thasos, see Osborne 2009.

51 IG I3 1453 G, 60, 133; cf. Andocides 1.83–4; Demosthenes 24.18. Other phrases imply similar motives, for example, the formula “so that everyone may know” (hop ō s hapantes eid ō si); IG II2 223A.13–15.

52 This is not to imply that democracy required or achieved full literacy among the citizens. Classical Athens was still a largely oral society (Thomas 1992), and publicly displayed texts could serve multiple purposes short of reading by individuals. The monuments alone could serve as symbols of laws and decrees whose content circulated orally. Similarly, literate citizens could disseminate the information contained in these inscriptions orally to non-literate citizens. On literacy levels in classical Athens, see Harris 1989; Missiou 2011. For doubts about the connection between the “disclosure clause” and democracy, see Sickinger 2009. Sickinger points out that these clauses occur primarily on honorific decrees and are designed to encourage others to emulate the deeds of the honoree. Sickinger does not, however, question the general connection between publication and the desire of the democracy to keep citizens informed.

References

Anderson, G. 2003. The Athenian Experiment: Building an Imagined Political Community in Ancient Attica, 508–490 BC. Ann Arbor.

Bers, V. 1985. “Dikastic Thorubos.” In P. A. Cartledge and F. D. Harvey (eds.), Crux: Essays in Greek History Presented to G. E. M. de Ste. Croix, 1–15. London.

Bleckmann, B. 1998. Athens Weg in die Niederlage. Stuttgart.

Bleicken, J. 1987. “Die Einheit der athenischen Demokratie in klassischer Zeit.” Hermes 115: 257–83.

Bleicken, J. 1994. Die athenische Demokratie. 2nd ed. Paderborn.

Blok, J. 2005. “Becoming Citizens: Some Notes on the Semantics of Citizen in Archaic Greece and Classical Athens.” Klio 87: 7–40.

Blok, J. 2007. “Fremde, Bürger und Baupolitik im klassischen Athen.” Historische Anthropologie: Kultur, Gesellschaft, Alltag 15.3: 309–26.

Boedeker, D. 2007. “Athenian Religion in the Age of Pericles.” In L. J. Samons II (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Pericles, 46–69. Cambridge.

Boedeker, D. and K. A. Raaflaub (eds.). 1998. Democracy, Empire, and the Arts in Fifth-Century Athens. Cambridge MA.

Boegehold, A. 1995. The Lawcourts at Athens. Princeton.

Boegehold, A. 1996. “Group and Single Competitions at the Panathenaia.” In Neils 1996: 95–105.

Brock, R. 1994. “The Labour of Women in Classical Athens.” CQ 44: 336–46.

Brulé, P. 1987. La Fille d’Athènes: La Religion des filles à Athènes à l’époque classique. Paris.

Brulé, P. 1996. “La Cité en ses composantes: Remarques sur les sacrifices et la procession des Panathénées.” Kernos 6: 37–63.

Camp, J. M. 2001. The Archaeology of Athens. New Haven.

Carey, C. 1997. Trials from Classical Athens. London.

Cartledge, P. 2002. “The Political Economy of Greek Slavery.” In Cartledge et al. 2002: 156–66.

Cartledge, P., P. Millet, and S. von Reden (eds.). 1998. Kosmos: Essays in Order, Conflict and Community in Classical Athens. Cambridge.

Cartledge, P. E. Cohen, and L. Foxhall (eds.). 2002. Money, Labour and Land: Approaches to the Economies of Ancient Greece. Cambridge.

Christ, M. 2006. The Bad Citizen in Classical Athens. Cambridge.

Cohen, D. 1991. Law, Sexuality and Society. The Enforcement of Morals in Classical Athens. Cambridge.

Cohen, E. E. 1992. Athenian Economy and Society: A Banking Perspective. Princeton.

Cohen, E. E. 2000. The Athenian Nation. Princeton.

Connelly, J. B. 2007. Portrait of a Priestess: Women and Ritual in Ancient Greece. Princeton.

Connor, W. R. 1971. The New Politicians of Fifth-Century Athens. Princeton.

Coulson, W. D. E., O. Palagia, T. L. Shear, Jr., et al. (eds.). 1994. The Archaeology of Athens and Attica under the Democracy. Oxford.

Cox, C. A. 1998. Household Interests: Property, Marriage Strategies and Family Dynamics in Ancient Athens. Princeton.

Develin, R. 1989. Athenian Officials 684–321 BC. Cambridge.

Eder, W. (ed.). 1995. Die athenische Demokratie im 4.Jahrhundert v.Chr. Vollendung oder Verfall einer Verfassungsform? Stuttgart.

Eder, W. 1998. “Aristocrats and the Coming of Athenian Democracy.” In Morris and Raaflaub 1998: 105–40.

Finley, M. I. 1980. Ancient Slavery and Modern Ideology. New York.

Finley, M. I. 1981. Economy and Society in Ancient Greece. Eds. B. D. Shaw and R. P. Saller. Middlesex.

Fisher, N. 1998. “Gymnasia and the Democratic Values of Leisure.” In Cartledge et al. 1998: 84–104.

Fisher, N. 2011. “Competitive Delights: The Social Effects of the Expanded Programme of Contests in Post-Cleisthenic Athens.” In Fisher and H. van Wees (eds.), Competition in the Ancient World, 173–219. Swansea.

Forsdyke, S. 2001. “Athenian Democratic Ideology and Herodotus’ Histories” American Journal of Philology 122: 333–62.

Forsdyke, S. 2002. “Herodotus on Greek History, 525–480.” In I. de Jong, E. Bakker and H. van Wees (eds.), A Companion to Herodotus, 521–49. Leiden.

Forsdyke, S. 2005. “Riot and Revelry in Archaic Megara: Democratic Disorder or Ritual Reversal?” JHS 125: 73–92.

Forsdyke, S. 2006. “Land, Labor and Economy in Solonian Athens: Breaking the Impasse between History and Archaeology.” In J. Blok and A. Lardinois (eds.), Solon: New Historical and Philological Perspectives, 334–50. Leiden.