26

THERE YOU HAVE IT, THE REAL AND TRUE HISTORY OF Bellinas. After three days locked in the schoolhouse, I have finished my testimony, and with little time to spare. No matter what happens next, I have reclaimed my future in some small way. As for reclaiming my body? “Trust the divine timing of the universe,” as the father of my child says when ministering to the Bohemian Club. I hate to give weight to his platitudes, but he is right in this. I always knew that I was meant to be a mother, even if this is not how I expected it to happen.

My animal friends, the gray fox and the bobcat, have deserted me since the creep of softest pink announced the coming dusk and with it, my fate. So eager to finish writing that I missed the three-o’clock rainbow. Not so much as a bobbing quail has appeared for hours. I am not alone here; nor will I be for long. Have I been too harsh on the residents of Bellinas? I have met in my old life, in New York, men who banned their wives from coffee or alcohol or desserts or tired anecdotes at tired artistic dinner parties. Friends and co-workers at the fashion magazine snuck out with me for coffee, for cookies, for pastries if their husbands wished them to alter their diets for reasons of improving their bodies or their moods. And of course there is no shortage of women the world over who drink away their troubles in glasses of wine instead of cups of fragrant tea. Is the problem not with Bellinas at all, then, but with the controlling edge that is excused as artistic temperament? In men, it rarely comes to good, but such mysteries are not for me to ponder. Maybe the problem is with marriage itself. So what if part of me thinks that Guy deserved what he got? I am glad now that he is gone. It is a relief.

A question I have been mulling over as I recount the unlikely events that occurred in Bellinas: What good have the Classics ever done me? I could have been a scholar, that is true. I won an award, you know. For my thesis: “The Rape of Married Women by the Lesser Gods of Ancient Greece.” How did I not see it coming when I made it all happen? I could have been a scholar, a writer. I once was a wife. I am none of those things now. The Father of History has sired a world of men who are liars, invaders, rapists, murderers. It is women who really remember, because it is women to whom all the violence and betrayal is done. I will take this opportunity to nominate my beloved Anna Nováková the Mother of History, though I know only what little Mia has told me of her. Then again, as I contemplate my impending motherhood, I think that every mother is the creator of some history, is she not?

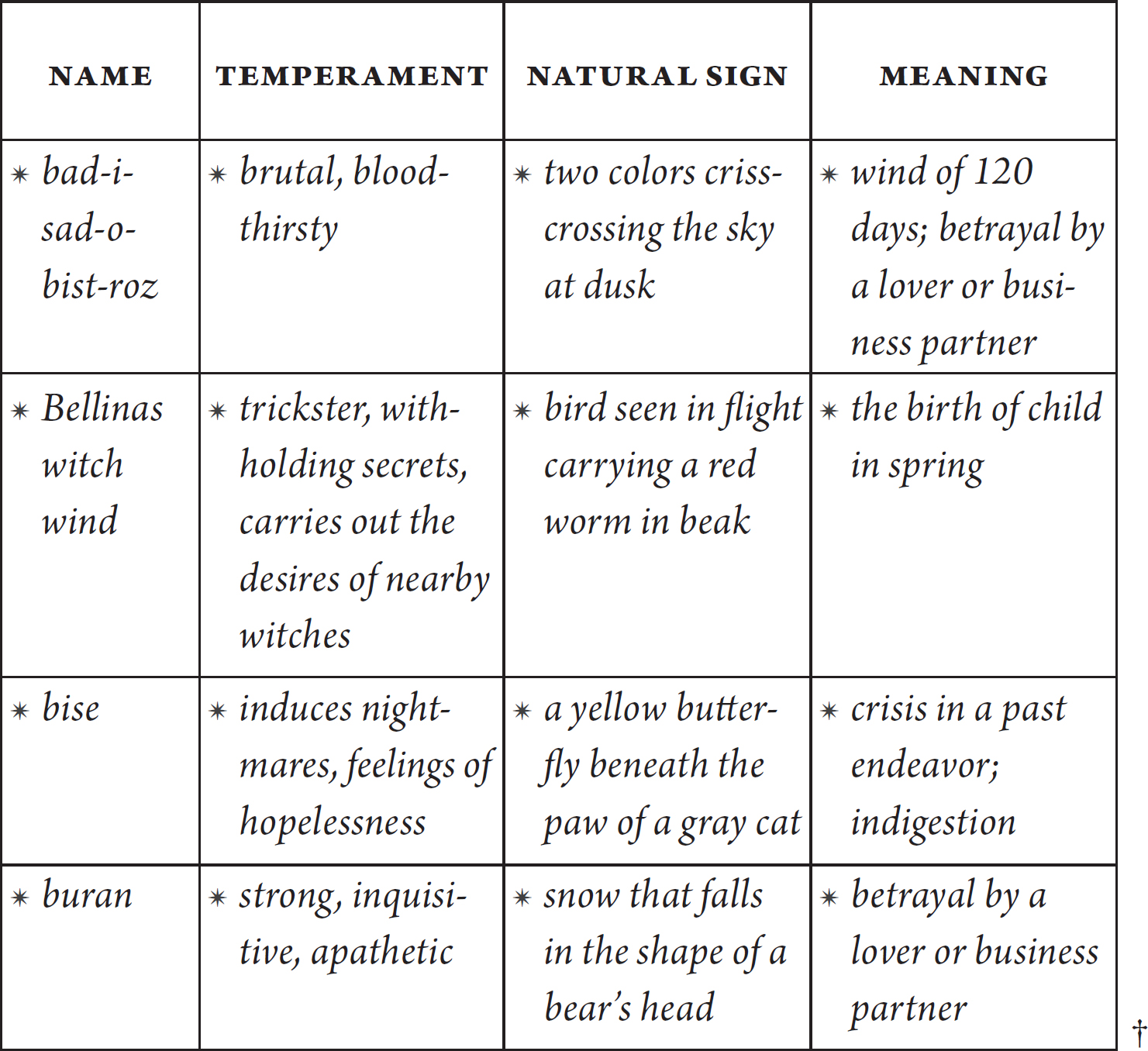

In The Book of Weather, the great winds of history are named and ordered by region and temperament. This pocket-size edition—of which there are too few nowadays!—found me when I was at my lowest point. Have I let my romantic tendencies invite a belief in at least one kind of magic? Guy would call it superstition, but I can say only that the right book has always found me exactly when I needed it.

I am left wondering about a name for the winds of Bellinas. Anna Nováková gives the winds of history their proper names. There are the simoom winds of North Africa, the so-called poison winds. When the Greeks were hard-pressed to defeat the Persian army, Herodotus tells us the simoom had no trouble disappearing it entirely en route to Ethiopia. So hated are these winds that the nation of Psylli, says the Father of History, declared war against them. The khamsin of Egypt are blamed for so much destruction, they are known as the ninth plague of Egypt. And yet they are still less frightening than the clouds of dust that rain blood from the sky—red dirt from Africa—into the streets of Europe. The mistrals of France bring insanity. The Mediterranean sirocco suck all feeling from the pens of poets. Criminals acquit themselves of violent crimes successfully by citing the malevolent influence of the sirocco. The föhn of the Alps brings sickness with such a regularity, the name of the wind is interchangeable with the disease it causes. Virgins and mares were historically shielded from these virile north winds lest they fall pregnant from their violence and produce demon children. The trickster winds that torment in the Sahara Desert are called waltzing djinns, akin to the dust devils that whip dirt and sand into fierce little cyclones on the sides of highways the world over. A waltzing djinn must have more fun leaping between dunes than highway exits, but they go where they are called, like the rest of us.

My Latin is rusty, but I believe the root for the word soul descends from anima, with the double meaning of wind and spirit. It seems as far back as language, the wind has been endowed with mood, with motive, with more destructive will than good. The ill winds outnumber the kindly. Or is it that they are more feared? The Santa Anas of Southern California have their morbid glory. Who has not heard of these fame-hungry gusts that disperse any illusion of Sunset Boulevard’s supposed romance from hills to surf and carry with them murder and divorce, according to the news? Not unlike the bad-i-sad-o-bist-roz of Iran and Afghanistan, except the duration is as long as their name. “The wind of one hundred and twenty days” and detested for each. They bring dust and desperation, drought and death. What name would suit the howls and shrieks sent by the witches of Bellinas? If these winds have caused as many of the suicides and shipwrecks as they say, then surely they are deserving of a name.

Do not discount the truth of the old wives’ tales in The Book of Weather, as wives’ tales too often are demeaned and dismissed. What is this history if not a wife’s tale? A truth revealed by unlikelihoods does not make it less true. A wind that blows against a flock of geese brings sour milk from a goat. A noisy wind that induces tears in children predicts a great fortune. A wind in the shape of a large cat delivers an enemy’s secrets, or a letter lost in the mail. For quickest conferral, Anna Nováková has indexed the winds alphabetically by name, by temperament, by signs to look for, and by the truths they bear.

The winds of Bellinas are something between the maestro and the meltemi. They blow with gale force overnight, and hardly at all in the day unless summoned. The thermometer reads a pleasant seventy-two degrees in the daylight hours here, and never dips below fifty-five degrees at night. The icy gusts of night make the dark feel far colder. Wind chill and loneliness pair unpleasantly well.

Smoke from the wildfires is barely detectable in the winds tonight, though the fires blazing in the surrounding towns must be encroaching by the hour. How black were the hills nearby. Any imperfection is kept at bay and remains on the other side of the forested hills that ring the town from lagoon to the Hidden Coast. To label the winds of Bellinas a basic witch wind would be the simplest, but the phrase feels imprecise. It is dark now, and they are really going. Like Iphigenia, I walk willingly to my fate, but my revenge will be that I have left the truth haunting Bellinas, as the nameless winds have haunted me. If I had been paying any attention at all, I would have noticed the clues that were all around us from the very beginning. How differently things might be today had I taken greater heed of the signs, the symbols—the brochures! Please do not take me for some wilting, sickly Lord Byron, carried to death by sirrocan howls.

What of my baby? I can protect her best with honesty. She will have the same too-blue eyes as the other children of the Bohemian Club. A true child of Bellinas. Conceived in a woozy trance under a Strawberry Moon, as her family—that is what they would call themselves—sang her into existence from a pool of lithium-laced spring water and help from a virile north wind. She will not be the first child born from an act of nonconsensual passion. The Classics are full of them. There is Arca. Despoina and her brother Arion. Helen of Troy, and Heracles the hero. I hope that my child knows none of their names. I will not have her burdened by a history that did nothing to save me.

Guy and I once planned to see a famous poet read at a bookstore at the bottom of Manhattan. We took the subway, a numbered train, from the iron gates of our university and emerged in metallic puffs of cold breath at the wrong stop. We wandered the streets, the snow piled in hard gray hills and not bothering us in the slightest as we ducked in and out of bars whose windows were lit with red neon letters and fogged with the flirtations of other lovers. We missed the poet’s reading, but I didn’t care. In front of a glowing blue-and-yellow sign, an eye and a hand above “Palm Readings,” he suggested we go inside, if only to keep warm. My superstitions and warnings from Constance the Elder were checked by the hope that Guy would kiss me later, and I followed him. A young woman, her toddler asleep in a nest of blankets on the floor of what was her living room, took us separately into her kitchen to read our futures from the lines on our palms. Guy never told me his fortune. He tried, but I stopped him, insisting it was like wishes blown over candles on a birthday cake. Did she predict his death by a witch, his wife, half a world away? Perhaps if I had broken the secret, I might have broken the spell. After all, I never told Guy what she said to me either: “You have too much air. But it’s the fire that will get you.”

It is some small solace that books line one wall of the schoolhouse. Their company is my last source of comfort. After my parents’ car accident, I stayed in bed, escaping into the realm of fantasy when my reality felt too burdensome. In college, when my grandmother died of an ordinary heart attack, I consoled myself by reading the words of Homer and Herodotus recorded in the triangles and the circles, the n’s and k’s of Ancient Greek. What little I have done with my education. The slow slide of blue day into vivid dusk is complete. How quickly my time dwindles. The sky goes now from pink, with bands of orange, to indigo and navy. Tonight is the night. I can feel it. It must be. No guiding divination from Anna Nováková is necessary, though she does warn that a wind that stripes the sky in paint will bring visitors.

I must deface my beloved Anna Nováková if I am to save myself, I think. She has been my saving grace—the mother of witches. If there should be purpose in everything, as preached by Manny, then I take mine in the discovery of her words. My own account, this history as real and true as any recorded by Herodotus, is now folded into the paperback cover of Anna Nováková’s Book of Weather. A tenth Sibylline Book to consult in times of need. It was no trouble at all to pull the pages from their glue, the only scent that rivals for a place in my heart that of mist-covered eucalyptus and bay laurel in the morning light. As everything in the house on Rose Lane returns to its place by morning, I trust that my pages in The Book of Weather will return to our bungalow for safekeeping. My bungalow, I should say. This page, I have kept and folded between my own:

†From Anna Nováková, The Book of Weather, third edition, Československý Spisovatel Press, 1964.

I do not know what will happen to me, but I know it will happen soon. I can hear the whooshes of slim tree branches battling the approaching winds. Darkness has filled these windows at last. I never wanted to be a witch, but after Guy’s death by my magic, I cannot deny what I am. What does it mean not to want to be what you already are? To doubt what you wanted most in the world when it comes to you? If I am to be saved, it will be to deliver another child of Bellinas. I assume that it will be a girl, but a boy is also possible . . . If it is a boy, like Clytemnestra’s, I will whisper into his ears, when the time is right, this history to inspire the revenge on a deserving Father M.

AND THERE IT is. A knock. The scent of bay laurel in a wind laced with smoke and perfume.

History has few happy endings, and the Classics even fewer. Let me imagine one here before I climb across my barricade of school desks and picnic tables to end my claustration and confront my accusers.

“Darling, are you in there?” Mia would ask, knowing full well that I am.

“Are you going to turn me in?”

“Whyever would we do that, darling? Won’t you come out so that we can talk?” she would ask, and then she would sigh or untie a knot on her dress. Then my protection, little as it is, the desks and tables against the doors of the mission-turned-schoolhouse, would untangle itself to land in neat rows.

“I’m a murderer, Mia. I’ve killed my husband. It was an accident, I swear. Even if he deserved it, I did not mean to. Don’t you have to call the police or something?”

“I know it was an accident, darling. Set yourself free of blame. The men at the bonfire saw nothing. I’ve already reported him missing. He went diving for abalone and never came back. We are so very worried, but it does happen. He had been drinking. Just like the others. Another tragedy. Come out, please. The messy part will be over in the blink of an eye.”

“You don’t want revenge? I betrayed your trust. I told Guy about Manny and the baby . . .”

“How sad that your imagination has been shaped by men, and so you can only see what they would do. Come out, Tansy. Come live with us as a witch and a widow. We offer you an entirely new way to see the world. We don’t want to hurt you. The wind does have a mind of its own. He was my cousin, but I must say that we have all felt that Guy was not good enough for you. What you cannot do for yourself, Nature will take into her own hands.”

“What about the baby?”

“We’ll raise her all together as a family. That’s what we’re trying to build here. A perfect community. All the girls have given birth at Rose Manor. Witches make the best midwives. Didn’t you see the volume on your mantel? The Book of Midwifery by Anna Nováková.”

She really does know exactly what to say to calm one’s fears. And how soothing that familiar melody sung by the women and carried by the wind. California is not perfect, but being freed of my marriage, I might be able to embrace the magic in the nature here. It is so beautiful. I shall let the sun pierce the silky gauze of my dress to warm my skin and fill my breasts with milk for my baby. Sunlight is very good for that, I have heard.

“Can you forget this world of men? The rules of societies built on their histories?”

And I would answer as a real and true member of the perfect town of Bellinas, “Yes, I can forget the histories left by men.”

Is that how it will go? I can raise my little Helen in Bellinas. I hope she arrives in time to celebrate the festival of fertility in Bellinas. I believe it’s on the spring equinox. Families picnic on the beach and fly kites. It is Manny’s, her father’s, favorite holiday. It may even align with the ancient Greek festival of flowers, Anthesteria, in honor of Dionysus and the blooming flowers of spring. Manny will want to name our daughter after a flower, however. Anemone, then, perhaps I can convince him. A lovely family of flowers. It means “daughter of the wind” in Greek. I will call her Ann, or maybe Mona, for short, and she can go to school in this very room. Her education will be different, better than mine. When she’s old enough, I’ll introduce her to my Book of History, hidden within Anna Nováková’s Book of Weather so she can know the truth. Whatever happens to me when I get up to answer the door, I now have faith in my magic.

I am counting on discovering this history again, on its appearing in its place on the fireplace mantel by morning. To hold like a life raft this touchstone to remind me who I was before I was a witch of Bellinas. To remind my daughter that a life controlled by men is a life of no magic at all. Surely, there is no spell strong enough to destroy my need for a book, bound by magic different from the weather’s. The wind calls my name, and it is time to answer. I am Tansy Green. I am a flower in bloom. A witch of Bellinas.