25

THE HAMMER

I got a tip to phone Swarthmore psychology professor and social constructionist Kenneth Gergen, who had a close relationship with Rosenhan during his time at Swarthmore. I shared with him what I knew about the study, about Rosenhan’s involvement, and about my inability to pin anything to the ground.

He interrupted my ramblings.

“To meet [Rosenhan] and talk with him, he was almost charismatic. Nice, deep voice with a very personable way of relating to people. He was a good networker. He kind of knew people who knew people, and he played the network. He was an excellent lecturer. I mean he just had a certain drama about him. But… a number of us in the department, and it wasn’t me because I was kind of a friend of his… people would say, ‘He’s a bullshitter.’”

Then he laid the hammer down: “If you’ve [only] got one or two examples of things that really happened as they are written in the paper, then let’s assume most of the rest was made up.”

I hung up the phone and sat still for a moment to take in his words. Could there be any truth to Kenneth Gergen’s offhand remark? Exaggerating findings and altering data to fit his conclusions were troubling enough, but inventing people out of whole cloth? That was inconceivable.

Or was it?

People I interviewed kept mentioning one young woman—with beautiful hair, they always added—who worked as Rosenhan’s research assistant as an undergraduate at Swarthmore and then continued on in the same capacity at Stanford. If anyone had the answers, they told me, it would be that student. Luckily, Bill remembered her first name: Nancy. With a few educated guesses about the year she graduated, I tracked down a Swarthmore alumni Flickr page, and there, among the middle-aged revelers, I found a picture of a striking woman with long gray hair. She looked straight at the camera, her eyes smiling but her lips sealed, as if flirting with the camera, saying, You got me. Her name listed on the page: Nancy Horn.

Over the next few months, I spoke to Nancy Horn four times. We discussed her eclectic work as a therapist, which combines different treatment approaches. We discussed her son, who lives with serious mental illness and has spent time hospitalized and homeless. She regaled me with stories from her undergraduate years at Swarthmore, where she majored in psychology, played volleyball, and met a “charming, witty, incredibly smart” professor named David Rosenhan. She helped him with his altruism research, corralling the children into the testing trailer, rigging the bowling game so that each child would win or lose. She took on a variety of roles in Rosenhan’s life: administrator, teacher (sometimes she would help with his classes), researcher, and friend.

“I think he always made people feel special,” Nancy said.

The two had lost track of each other in the final years of his life. She learned of his death from a newspaper or academic journal announcement—she couldn’t remember which. But she never stopped thinking of him. “I do think about him often… I think he was my biggest influence as a role model of a great psychologist, absolutely, a truly great psychologist. And he was great because he was well read, he was wise, he didn’t have some sort of narrow-minded sort of focus for himself. He was open to ideas and smart and definitely cared about people, which is what I got into psychology for.”

Down to the real reason I called: the pseudopatients.

She recalled working with two graduate students at Stanford—Bill Underwood and Harry Lando—as their point person. She was the one whom Harry contacted from the pay phone and the one he read his medical records to. She also said she visited both men in their hospitals.

“Did Rosenhan prep you for what to look for? Did he say look for certain…”

“No.”

“He just trusted that you would…” As I trailed off, I thought about myself as a recent college grad. I would never have been responsible enough to monitor someone’s mental health. (I’m still not.) Wise beyond her years, Nancy devised a method to examine them for any signs of distress. She looked at their speech patterns, asked them what they were doing to pass the time, inquired about their medications, made sure they weren’t emotionally unstable.

“I looked for fifty things at once,” she said. “You know, if you’re in a crazy situation, it can be crazy-making. So you have to be sure somebody isn’t going nuts from being in the situation.”

Despite Nancy’s maturity, the fact was that Rosenhan left a huge responsibility in an assistant’s hands. This was at best unprofessional. Forget the paper’s transgressions: Even if the study’s data were flawless, there’s no way the Institutional Review Board (IRB), which oversees academic research to protect “the rights and welfare of human research subjects,” would approve it today. It would pose too great a danger to participants, hospital patients, and, to some degree, its research assistant.

But what of the other six pseudopatients—the Beasleys, Martha Coates, Carl Wendt, and the Martins?

Nothing. Despite their closeness, Rosenhan had kept the identities of all but two of the paper’s pseudopatients hidden from even his research assistant. I walked her through the information that I had gathered from Rosenhan’s notes and manuscript. I told her about Sara Beasley, #3, who almost swallowed her medication to drown out her anxiety, and Robert Martin, #6, the pediatrician who developed paranoia about his food.

“He thought his food was being poisoned? That’s not good.”

“No. And if you heard that, you would have said we need to get him out, right?”

“Oh, are you kidding? Oh my God, he’d be out in a heartbeat. That would be ridiculous. Oh, I’d be so upset if I heard that,” she said.

When I described Laura Martin, #5, the artist, she asked, “That was the one at Chestnut Lodge?”

“Chestnut Lodge?” Listening back to my recording, I hear my voice pitch up. This was a solid lead at last, a counterweight to Kenneth Gergen’s suggestion that they might be made up. Chestnut Lodge was a famous private psychiatric hospital located in the shadow of DC, where Washington’s “eccentric” elite lived out their unraveling in style. Two popular novels, I Never Promised You a Rose Garden, which author Joanne Greenberg based on her hospitalization there and treatment by famous in-house psychotherapist Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, and Lilith, the story of a relationship between a patient and her attendant written by a former employee of the hospital, were huge bestsellers that were made into movies. Chestnut Lodge, I would find, was a dividing line in the battle between the brain and the mind—the place from which psychoanalysis sent its final flare.

Chestnut Lodge was founded on the idea that the asylum should be a safe place for a rich person to live with dignity. The end goal wasn’t really a “cure” per se; instead, patients would spend years (in some cases, a lifetime) on the gorgeously manicured grounds, going from tennis to art therapy and, of course, to daily talk therapy. The hospital did not partake in the hideous treatments that checkered psychiatry’s other venerable institutions—no lobotomies, insulin coma therapies, or electroshock here—and it even put off prescribing drugs. And then came Dr. Ray Osheroff, a depressed forty-one-year-old kidney specialist, who was admitted to Chestnut Lodge in 1979 and was diagnosed with “narcissism rooted in his relationship with his mother.” The Lodge employed “attack therapy” and “regression therapy” over the course of nearly a year, which only worsened his condition, as he lost forty-five pounds and paced almost constantly, upward of eighteen hours a day. Osheroff’s parents intervened and moved him to a more traditional psychiatric hospital, where he was diagnosed with depression, treated with antidepressants, and released nine weeks later. Osheroff sued Chestnut Lodge for malpractice (settling out of court for a rumored six figures)—a case that became about something larger than Osheroff, by proving that “psychiatry was a house divided,” said Dr. Sharon Packer in a belated obituary for Osheroff written in 2013. “The hallowed walls of psychoanalysis were tumbling down.”

Knowing all of this history, it is hard to believe how little Chestnut Lodge left behind. The Lodge’s heyday ended without fanfare when the veritable institution filed for bankruptcy in 2001 and the property was sold to luxury condo developers. Then, on July 13, 2009, the barking of an “aggravated dog” alerted the neighborhood that the historic building had gone up in flames. Everything was lost. Chestnut Lodge had hardly left a footprint.

But there are some among the hospital’s former employees who keep the memory of Chestnut Lodge alive. One psychologist, who also works at the NIMH, brought a scrapbook of pictures from her time there during our first interview. (How many former employees keep pictures from their old jobs—especially jobs located at psychiatric hospitals?)

“This is a summertime photo. See? The grounds are beautiful,” she said, pointing to the chestnut trees. She showed me the gym, and the pool, and recalled the time when a wedding party wandered among the trees in search of the perfect photo op, without realizing they had stepped onto the grounds of a psychiatric hospital. The psychologist had felt so proud, even as she shooed them away, to know that the setting was as beautiful and peaceful to outsiders as it was to her. “Please be kind to Chestnut Lodge,” she said to me. “I really loved it.”

I told her about my mission—about the Rosenhan experiment, about tracking down the pseudopatients, about the possibility that one of the undercover agents had infiltrated the Lodge. She had not heard about the study happening at Chestnut Lodge, but she admitted that it was long before her time. Luckily for me, when the hospital was being dismantled and picked apart after its bankruptcy and before the fire, she had squirreled away a metal filing cabinet that held the hospital’s patient records—three-by-five cards printed with the names of and information on each patient who had visited the Lodge since its inception: length of stay, diagnosis, dates of admission and release—files that would have been thrown out without her intervention. I was thrilled: This would be more than enough to find my pseudopatient. She agreed to see if anyone matched the artist’s description and length of stay, though she refused my offer to help her dig, citing patient privacy laws.

She went her way, and I went mine.

If Chestnut Lodge checked out, and I could find Laura Martin, pseudopatient #5, I would feel somewhat better about the whole enterprise. There was hope: Rosenhan had visited DC for six days in 1971—smack-dab in the middle of the study, and likely the time when Laura Martin, the only pseudopatient who attended a private hospital, went undercover—so it was possible that he had visited Chestnut Lodge then.

I returned to Rosenhan’s manuscript to study the parts about Laura, the famous abstract artist who was hospitalized for fifty-two days and the only subject to receive the diagnosis of manic depression. I reread a chapter in his unpublished book that recounted the time Rosenhan was summoned to Laura’s hospital to consult on an “interesting case,” only to discover it was his own pseudopatient.

Rosenhan took detailed notes on the case conference of his pseudopatient, quoting Laura’s psychiatrist, who used florid terms to diagnose her using her paintings—“The ego is weak,” the doctor said as he examined one of the six works she created at the hospital. Despite his gross misjudgment, Laura did use the opportunity to do some work on herself, and, in Rosenhan’s description of that process, the outline of a woman and an artist emerges. Rosenhan described the worries that she faced about her pediatrician husband, whom she feared was working himself into an early grave (this was Bob, who in his own time as a pseudopatient would obsess about the food); her concerns about the younger of her two sons, Jeffrey, who had begun experimenting with marijuana; and her issues with honing and maintaining her creativity as a painter.

I then asked dozens of people who knew Rosenhan if he had befriended any famous female artists in his lifetime, but no one had any solid suggestions. I made lists of famous female abstract artists from that era and phoned art historians. They floated several names: Anne Truitt, Joan Mitchell, Mary Abbott, Helen Frankenthaler, all dead ends. The National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington sent me a list of books. There were false positives. The mother of one of Rosenhan’s Swarthmore students was a pretty famous sculptor. No dice. I emailed Judith W. Godwin, an abstract artist from New York whose work hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She responded to my email with the kind but firm: “I didn’t take part in this study. Good luck in your research.”

And then a hit.

Grace Hartigan, who was born in Newark in 1922 and died in 2008, began her career as a draftsman in an airplane factory. With no formal training, she started re-creating Old Masters. In the 1960s, she incorporated images from popular culture into her intensely colorful work—an early version of pop art. “I didn’t choose painting,” she said. “It chose me. I didn’t have any talent. I just had genius.”

She married four times. Her first husband’s name was Bob. Ding, ding, ding! Only issue: Her first husband was out of the picture by 1940. Not so ding, ding, ding-y. Here’s where I wanted to take a victory lap: Her fourth husband, Dr. Winston Price, an art collector whom she wed in 1960, was a famous epidemiologist from Johns Hopkins University, obsessed with finding the cure for the common cold. There was little he wouldn’t do for his research—he even injected himself with an experimental vaccine for viral encephalitis, which gave him spinal meningitis, starting a decline that went on for a decade until his death in 1981.

Could these two have been my Martins? Winston Price put his life on the line for his work, so admitting himself to a psychiatric hospital wouldn’t be a stretch. Grace, who struggled with her own demons, including alcoholism, had a vested interest in the study of madness and its overlap with creativity. It seemed plausible to me and to Grace’s biographer, Cathy Curtis, who added this: Grace Hartigan’s son Jeffrey (same name as Laura’s son, according to Rosenhan’s notes) had lifelong issues with drug abuse, just as Laura worried that her son Jeffrey smoked marijuana. But Cathy tempered my confidence. “At the tender age of 12 [Grace Hartigan] sent him to live with his father in California. She really had very little to do with him the rest of his life,” Cathy said. “She would tell people she hated him.”

“On the bright side,” Cathy added in an email, “if I had to quantify the Hartigan possibility I’d say 80 percent.”

Eighty percent. I’d take those odds. Yes, Grace had only one child, not two, and likely didn’t care enough for the child to worry about him, but these are things that could have been exaggerated or miscommunicated to or by Rosenhan. To shore up the possibility, Cathy recommended I contact Grace’s longtime assistant Rex Stevens, who worked with her for twenty-five years.

“It’s not Grace.” This was Rex Stevens. He said it with such authority that it felt like a shove. The timeline was wrong, he said. The description of her painting was wrong. The relationship with her art, with her husband, with her son—all wrong. But the most damning part from his perspective? She would have told Rex.

“I know everything about her,” he said.

I brushed this phone call off as a product of resentment. I’m sure I would have been dismissive if I heard that someone I knew for that long was hiding something this big. I contacted a researcher at Grace’s archives at Syracuse University, which contained twenty-five linear feet of correspondence, notebooks, and diaries from the bulk of her career. But the researcher could not find one letter to or from David Rosenhan. The odds were dropping precipitously that Grace Hartigan was my Laura Martin.

Pseudopatients #5 and #6 were still unaccounted for.

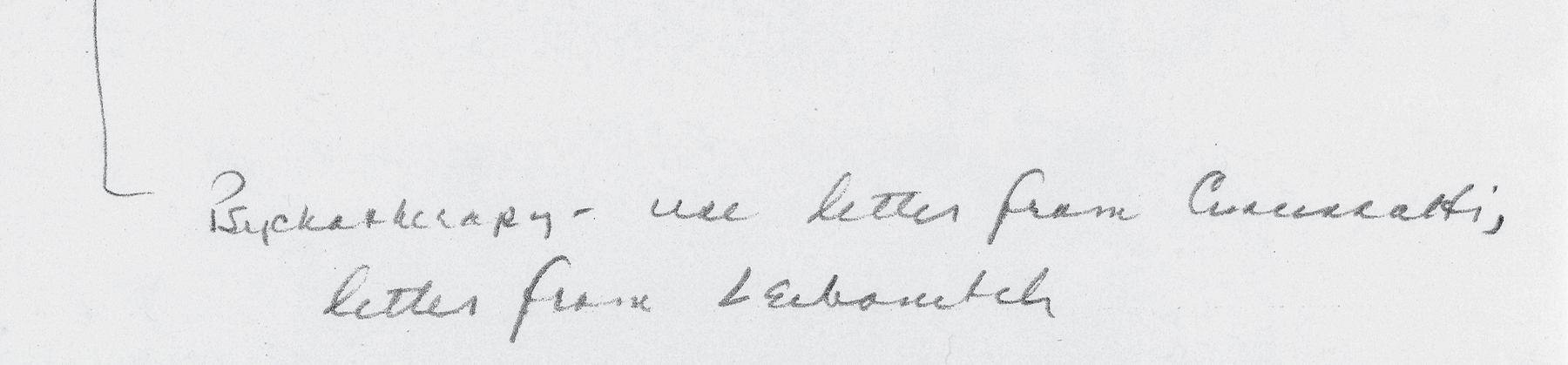

During one of my earlier research trips in Jack’s condo, when I had stumbled across the outline of Rosenhan’s unpublished book with handwritten notes that eventually led me to Bill Underwood, two other unexplored clues had intrigued me, too. Beautiful but almost indecipherable letters (that took the help of both Florence and Jack to decode) spelled out: “Letter from Leibovitch”; above it: “Psychotherapy—use letter from Cincinnati.”

I had kept them in the back of my mind as possible leads, but I didn’t know how to connect them until I stumbled on a series of letters written by a woman named Mary Peterson nestled in a draft of the sixth chapter of Rosenhan’s unpublished book. The letters detailed Mary Peterson’s experience at Jewish Memorial Hospital in Cincinnati.

Cincinnati.

One letter to Rosenhan from Mary Peterson described the twelve days that she spent on Jewish Memorial’s psychiatric ward. Mary narrated the story of her hospital stay into a recorder and sent the tapes to Rosenhan, who asked his secretary to transcribe them. The transcriptions, which were only partially completed, detailed an extensive cast of characters, among whom quite a few names matched the descriptions of patients in Rosenhan’s notes on Sara Beasley, pseudopatient #3. Mary and Sara also had similar descriptions of their first anxious night on the ward, when Sara almost swallowed her pills.

“Got one of them!” I scrawled in the margins of my notes.

Rosenhan had kept Mary’s envelope, so I had her address, which helped me track her to Cleveland, Ohio—only to find out that she had recently passed away and that her husband (named John, also the name of the husband of Sara, pseudopatient #2) predeceased her. Her obits made it clear: This woman was filled with vigor. I read through the cooking columns she had written for the local paper and ordered her self-published book of adoring short stories about living in the Queen City. “An angel on wheels” is how a local writer described Mary Peterson, who was often spotted on her pink bicycle. “Sometimes I think there are angel wings protruding from her back when I see her biking!” Now I was doubly disappointed—not only would I never get a chance to ask her about the study, but I would never get to meet this remarkable woman.

But my excitement masked some problems. First, Mary Peterson would have been too young to fit Rosenhan’s description of someone “gray-haired” and “grandmotherly” in 1969. Mary’s occupation—an economics professor instead of an educational psychologist—didn’t fit. Mary Peterson’s stay in the hospital was longer than Sara Beasley’s, another issue. Her husband, though also named John, was an architect, not a psychiatrist. But perhaps Rosenhan had changed autobiographical details to preserve identities, as we’d now seen him do to some degree with both his own and Bill’s records (though age, occupation, and physical description remained intact). Why else would these letters be filed with drafts of his unpublished book?

A quieter issue was that Mary Peterson spoke to Rosenhan about her long-standing history of depression and anxiety. She confessed as much in her letters, telling Rosenhan that she had spent the last decade on tranquilizers and regularly saw a shrink. Would Rosenhan have sent a woman with a history of mental health issues in as a pseudopatient?

But the hardest fact of all to assimilate into the narrative was the timing: If her notes were correct, Mary was admitted to Jewish Memorial Hospital in 1972, right around the time Rosenhan handed in his first draft of “On Being Sane in Insane Places” to Science, making it impossible that she was Sara Beasley, the third pseudopatient who helped kick-start the study in 1969.

I contacted Mary’s surviving sister and childhood best friend. Neither recalled any mention of the study. Neither had heard of David Rosenhan.

Finally, I shared the letters with Florence, the keeper of the files, to get her take. With her clinical eye, honed from years as a psychologist at an acute care facility and working with the “worried well” in her private practice, I believed her when she concluded: “There’s no way that Mary was a pseudopatient. She was a real patient.”

Why, then, did Rosenhan file this inside his unpublished book on the pseudopatients? If the letter had arrived only after his study, I wondered if “use letter from Cincinnati” could mean that he’d planned to supplement his discussions in the book with Mary’s experiences. It was a possibility, at least, though he had not yet used any hospitalizations other than the pseudopatients’ in the existing drafts of the book.

In addition to Mary’s letters, Rosenhan kept among his notes two journals: the first, one-hundred-plus pages from a Swarthmore undergraduate who in the summer of 1969 spent a month at Massachusetts General Hospital observing their psychiatric unit; and the second, unfinished diaries from two Penn State undergraduates, who, following the publication of Rosenhan’s study, went undercover in Pennsylvania psychiatric hospitals. Why had Rosenhan kept these files, yet retained none of his own pseudopatients’ notes?

More questions—zero answers.

Despite a glimmer of hope, the Beasleys, pseudopatients #2 and #3, and Martha Coates, #4, remained at large.

I naively thought that Carl, the recently minted psychologist whom Rosenhan feared was becoming addicted to the pseudopatient charade, would be simple to track down, thanks to reporting done before me. Several people had suggested that Martin Seligman, considered “the founding father of positive psychology,” who coined the term learned helplessness, was a pseudopatient. His biography matched up with only one: Carl, my #7. When I reached him and eventually interviewed him, however, he delivered the bad news—he was not Rosenhan’s pseudopatient, though he did go undercover at Norristown State Hospital with Rosenhan for two days in 1973 after the publication of “On Being Sane in Insane Places” to help Rosenhan gather more color for his book. Medical records I tracked down confirmed this.

So it was back to square one. If Rosenhan’s notes were to be believed, Carl’s age distinguished him. He seemed to be somewhere between thirty-eight and forty-eight, high for a newbie psychologist who had only recently received his clinical PhD. I knew he wasn’t at Stanford because the university didn’t offer an advanced degree in clinical psychology, meaning that Carl likely came from another institution, and, let’s be honest, that institution could be anywhere on the East or West Coasts (really anywhere in between, too). Even though I now considered Rosenhan to be at best an unreliable narrator, he was the only guide I had. But after hundreds of emails exchanged with anyone ever connected with Rosenhan, hours spent on the phone, and days sorting through his papers and correspondences to find any legitimate clues, I was giving up hope. No one fit the bill—until one finally did.

I kept coming across the name Perry London. It’s too bad Perry isn’t here, people kept saying to me. He’d know everything. Rosenhan and Perry worked and played together, co-authoring over a dozen papers, mainly on hypnosis, and writing two abnormal psychology textbooks together. Both were larger than life (though Perry, unlike Rosenhan, was large in stature, too); both had big booming laughs with big booming personalities. Perry would know all there was to know about the study—if anyone did—but he had died in 1992. The past was largely buried and gone until I arrived in the Londons’ lives, reopening old wounds in an effort to resurrect a man I’d never met.

His daughter Miv, a psychotherapist in Vermont, responded to my email and connected me with her mother, Vivian London, Perry’s ex-wife. I was properly vetted enough for Vivian to Skype with me from her home in Israel. She reminded me of my mother, and not just because they were both born in the Grand Concourse area of the Bronx, but also because they both have tough, take-no-shit exteriors. She shared the origin story of Perry and Rosenhan’s long-standing friendship. Vivian had connected them when Rosenhan worked as a counselor at the summer camp that her family owned.

“Everyone loved David,” she told me. He was the kind of counselor who could calm any homesick child, curling up beside a particularly upset one and soothing him to sleep. One summer when Rosenhan couldn’t attend, he sent a friend of his to take his place as a counselor. The following year this friend couldn’t make it and sent another friend in his stead, a boisterous young man named Perry London. Vivian and Perry started a summer fling that led to a wedding that also led to Vivian’s introducing Rosenhan to Perry.

When I mentioned “Carl Wendt,” my seventh pseudopatient, and the brief description that Rosenhan had included in his notes, Vivian stopped me. “Was he an accountant in Los Angeles?” she asked.

“He may have been.”

“That outline kind of matches a good friend of Perry’s in Los Angeles.”

“What was his name?”

She hesitated. I pressed. She pushed back. For the next five minutes, we debated. What if he doesn’t want to be found? she asked. If he kept this secret for this many years, maybe he didn’t want to expose it? I countered, explaining that there was nothing to be ashamed of and if his family wanted him to remain anonymous, I would follow their wishes. Eventually, she relented.

“Maury Leibovitz,” she said.

The name sounded so familiar. Vivian told me a bit more about this Maury character: Maury, like Carl, left behind a lucrative accounting gig in his early middle age to return to school and get a doctorate in psychology. He landed at USC, where Perry London became his teacher, mentor, and close friend. It was not implausible (at all!) that Rosenhan would have reached out to Perry for help in finding pseudopatients or that Rosenhan would have met Perry’s students during, say, a Friday-night Shabbat party (there were lots of those happening then). There was only one degree of separation between Rosenhan and Maury. And Maury fit the Carl bill to a T. Maury was even a fan of tennis, according to Vivian, which matched Rosenhan’s comment in a draft of his book that called Maury “athletic.”

When we logged off Skype, Vivian sent me a follow-up email. She was nearly as excited as I was. “It has become obvious to me that Maury is your man. I don’t even understand how I could have doubted it.”

I put on a pot of coffee, opened up my filing cabinet, which was filled with photocopies of Florence’s files, and resumed my dig. I was sure I had seen that name, Maury Leibovitz, before at some point, but I couldn’t place it. It didn’t take me long to find a reference. In that same outline of his book, marked in pencil—right by the CINCINNATI note that (mis)led me to Mary—Rosenhan wrote the word: LEIBOVITCH.

Did he mean Leibovitz?

It made so much sense. Not only did the two have a friend in common, but Rosenhan, I found, actually wrote a letter of recommendation for Leibovitz in November 1970, which meant that they also had a working relationship. This couldn’t be a coincidence, could it?

Maurice (“Maury”) Leibovitz wasn’t exactly difficult to track down. A Google search yielded a glowing New York Times obituary, published the same year Perry died. He was a major figure in the art scene in New York as the vice chairman and president of the Knoedler Gallery (now defunct after lawsuits for fraud long after Leibovitz’s death), a New York institution. New Yorkers regularly walk by the Gertrude Stein statue sculpted by Jo Davidson in Bryant Park, which Maury donated to the city.

With Maury Leibovitz came a theory about how a famous painter—pseudopatient #5, Chestnut Lodge’s “Laura Martin”—got involved with the study. Maury Leibovitz was a man deeply embedded in the art world. He could easily have been the bridge between Rosenhan and Laura.

Leibovitz was survived by three sons, an ex-wife, and a girlfriend. Of the sons, Dr. Josh Leibovitz, a Portland-based addiction specialist who had inherited his father’s interest in the mind, was the easiest mark. I left a message at his office and waited.

The next day a man’s Southern California drawl greeted me on the phone.

“I have reason to believe that your father was one of [Rosenhan’s] pseudopatients, one of the volunteers. Does this make sense to you at all?” I asked Dr. Leibovitz.

“Really?” he asked.

“Yes.” I could feel my heart jumping up to my throat. Seconds passed before he spoke again.

“No,” he said steadily. “I don’t believe that is true.”

I sighed. Over the course of the next twenty minutes I tried to make my case, which Dr. Leibovitz batted down: Maury would have been too old to be my Carl (Maury was fifty-two, when Rosenhan listed him as anywhere from thirty-eight to forty-eight, depending on the document, though, really, how much could we trust Rosenhan’s descriptions at this point?). He also was famously claustrophobic and would never have allowed himself to be confined to a mental hospital. And finally, the family was out of the country in Zurich during the time that the study took place.

“I’m sorry to disappoint you,” he said. “But it’s not my dad.”

But it was. It had to be. I pushed, positing the delicate question: Could it be possible he didn’t know his father as well as he thought he did?

“I’ve got to tell you, my dad was not a man to keep secrets. We were extremely close, so I doubt he would withhold something like that. I mean, I knew every detail of his life,” he said. “My dad would have probably written a book about it. He would not have been quiet about it.”

But why, I added, would the name Leibovitz, though spelled wrong, be in Rosenhan’s notes? I was like a bloodhound on a scent, and nothing he could say or do would knock me off it. I asked him to speak with his mother—she would have noticed that her husband was absent for at least sixty days (this was another issue with Carl: Some of Rosenhan’s documents said he was in for sixty days over three hospitalizations, while others said seventy-six days over four hospitalizations), so to my mind she would be the deciding vote. He promised to get back to me with an answer but denied my request to speak to her directly, effectively asking me not to waste his elderly mother’s remaining moments on earth.

At this point, I was clinging to the hope that this would all work out like a Doomsday cult member clings to her belief that the end is nigh even as the sun rises the next morning.

Another setback came that same week, this time in the form of a text message from the Chestnut Lodge psychologist, who had finished going through the hospital’s patient files.

“No one with the name or initials [of Laura Martin] was admitted in the late 60’s or early 70s.” Worse still, no person from 1968 through 1973 stayed at the hospital for only fifty-two days. The average stay, even into the 1980s, was fifteen months. “There was no way that this patient and her art work would have been presented during a [fifty-two-day] stay,” she wrote. To get a patient conference, you had to be in Chestnut Lodge for much longer. Doctors didn’t feel they knew their patients well enough to present a whole case study five weeks in. But Nancy Horn had recalled that someone had been there. Did she get it wrong or had Rosenhan lied about that, too?

As I was reeling from the news, I received this email from Dr. Leibovitz: “I spoke with mother and she is really confident that my father was never involved in such a study. She is 86 and a very private person. She was not interested in discussing any further. Good luck with the research. Keep me posted if you ever find out who that person was.”

Why did every single one of my leads go nowhere? Why had Rosenhan so obscured the path to these pseudopatients? What was he protecting? I felt betrayed by a man I’d never met. Had I spent my time pursuing phantoms in a fictional universe?

I returned to Laura Martin’s file one more time, this time with a furious, skeptical eye. I reexamined Rosenhan’s description in his unpublished book of the patient conference, where Laura’s psychiatrist used her paintings to reveal the underlying symptoms of her mental illness. Rosenhan quoted him directly: “The upper portion of the painting is the patient’s wish. Unable to handle the impulse life that surges beneath, she wishes for blandness. And perhaps in her better moments she can mobilize that blandness. But in the main it is difficult. She lacks the ego controls, on the one hand, and the impulses are too strong on the other. The blandness that she desires, representing both peacefulness and absolute control over her impulses, simply cannot be achieved. At best she can achieve moments of calm, punctuated alternately by depression and loss of control.”

The psychobabble continued. Her doctor moved on to four other paintings and then arrived at her sixth, and final, one. “The bottom half of the painting [is] much less intense… the colors here are better integrated… Mrs. Martin’s impulse life is better integrated.” A thick line separating top and bottom became proof to the doctor that Laura had improved under the watchful eye of his care.

Knowing now how far Rosenhan was willing to stretch truth, the problem here seemed unmistakable. This scene was too on the nose. Even the psychoanalytic interpretation of her paintings sounded clichéd, too much of a New Yorker cartoon depiction of a pipe-smoking analyst. And then the unlikely coincidence that Rosenhan himself was consulted on her case—he wasn’t a clinical psychologist and hadn’t worked with patients since his early days after getting his PhD, so why would someone in Washington, DC, call him to travel to see one of his own patients? Then there was the issue of how he managed to pay for these hospitalizations. He wrote in his private letters that he funded the hospitalizations himself (to avoid insurance fraud and other possible illegalities). Fifty-two days in one of the swankiest hospitals in the country would have cost a fortune, even then. Where did he get the money?

Kenneth Gergen may have been right after all. Did any of this even happen?