CHAPTER 9

NEW COLTS AND NEW 1911S

In 1970, Colt was in a bind: they wanted more people to buy their pistols than were buying them. Despite not having any real competition (the only choices you had back then were a Colt, or a USGI of one vintage or another) they were not selling as well as Colt wanted.

It's not as though Colt was standing still, however. To upgrade the 1911A1, they made some changes. One was the thumb safety, where they changed the always very small shelf to a larger, almost-useful shelf. The other was the bushing. The traditional Colt quality had been slipping for some time. Slapped-together 1911A1s did not shoot as well as earlier pistols had, and the customers were beginning to notice. Rather than crack the whip in QC and workmanship, Colt attempted to improve accuracy by means of a different method: the collet bushing. The standard bushing is a complex part, with its interior not simply being a ring the same size as the exterior of the barrel, but a circle with an oval section and some relief cuts, the manufacture of which was very involved – if you wanted to make it right, that is. So Colt took the bushing and changed the front end to a simple circle. Then they split the rear part of the bushing skirt into four fingers, each bent in to bear on the barrel. Then, they made the bushing out of spring steel instead of whatever alloy they'd been using before.

Slapped-together 1911A1s did not shoot as well as earlier pistols had, and the customers were beginning to notice.

Not only did Colt make unreliable pistols back in the 1970s, they made them with badly rollmarked slides. No, this rollmark was not buffed off in polishing. At least not after it left Colt.

A Colt commemorative, this one for the DEA.

The barrel was changed slightly: the front end was the same diameter as always, but back of that it was relieved just a bit, enough so that you could see the difference in diameter.

The idea was straightforward: the bushing fingers slide over the smaller-diameter section of the barrel without binding. But as the slide goes forward, the bushing fingers ride up on the larger-diameter part of the barrel, centering it up and increasing the repeatability of closing. The barrel will be spring-loaded to center in the slide. Accuracy is therefore improved. And you know what? It actually worked. By using a spring-loaded self-centering part, they increased the accuracy of the barrels. Only one problem: the danged fingers broke. Not often, but when they did, getting the gun apart to replace the bushing was a real hassle. Worse yet, once you found that you have broken a bushing, you are always going to break bushings. Why?

Simple: the same lack of Colt detailwork that got them in the fix in the first place. You see, if the tunnel down the slide, the one the barrel is enclosed by, is not straight and square, then when the slide closes, one of the collet fingers is going to take more of a load than the others. If the bushing slot that the bushing locks into is not milled precisely, the bushing gets held cock-eyed, and one finger takes most of the load. If the dimensional problem is big enough, or you shoot it enough, the heavily-loaded finger will break. And since the problem is lockup and dimensional, the replacement collet bushing won't fare any better than the previous one did.

Soon, shooters who bought new Colts took the collet bushings out and had gunsmiths replace them with properly fitted original-style bushings. The whole episode was a fiasco, and Colt ended up with a new pistol, the MKIV/Series70, that differed from the old only in the thumb safety. I've read that it took as late as 1988 for Colt to replace the collet bushing. Well, maybe as a part in the catalog, but I was working in gun shops starting in 1976 and as an IPSC shooter and gunsmith starting in 1978, and I know that I saw brand-new Colt Series 70 guns with old-style bushings, right from the factory when I worked then. They were definitely sending merchandise out the door without the vaunted new bushing for years before they finally bit the bullet and 'fessed up.

To give you an idea of just how badly Colt had gotten themselves sideways, in January of 1981 I attended the Target-world National Championships. At that early date, with no national organization (the USPSA would not be formed until 1984) practical shooting was kind of like drag racing: any group who wanted to, who was drawing competitors from more than the local states, could call themselves a Nationals. Targetworld, an indoor range and gunshop (and still in business, the last time I drove by in Cincinnati) held their Nationals, and I was there. On signing up, I did a bit of gamesmanship, something that became a hallmark of IPSC shooters in general: I scanned the list of who was where, and decided that I really needed to be in the “Professional” category and not the “Amateur” one. End result: my score won me a gun in Pro, where the same score in the much more heavily-enrolled Amateur would have gotten me nada.

My prize? A brand-new Colt government Series 70, blue, in .45. And that gun, out of the box, could not go through a full magazine without a malfunction. The malfunctions were varied, too. That gun taught me a lot about gunsmithing, and I imagine a whole lot of other Colt customers felt the same way, for that was the beginning of the custom gunsmith build-up. A whole lot of the “1911s aren't reliable, you have to send them to a gunsmith just to make them work” attitude came about because of that era of Colt.

Along the way, Colt also fell prey to the commemorative craze. Begun by Winchester, who would make a special model of anything, with “engraving” and “gold inlays” and whatever doodads seemed appropriate to the occasion that was being honored, Colt made a special set of military battle and theaters of war commemoratives. The whole idea behind a commemorative is that those who want to remember the occasion will be willing to pay a premium, over and above the extra work and cost of the extra work and materials. Well, the Winchester collectors (or enough of them) were looney enough to build the economic scaffolding of a commemorative market. Colt collectors were much less so. Colt did not do as well with the commemorative market as Winchester did.

And they were poised to make matters even worse.

In 1983 they announced their next generation 1911: the Series 80. As a sop to liability concerns (something for which Colt is infamous) they installed an extra safety gizmo. The parts blocked the firing pin until the trigger had moved the special plunger out of the way. The changes meant the Series 80s had four new parts, and two others that had to be modified. Gunsmiths hated it, as it made the work to get a decent trigger job (by then required work on Colts) more difficult. It also meant more parts to lose in cleaning, to break in use, and to go wrong at the worst possible moment. The design also had a drawback in operation: you didn't know if it was working properly, in general or in particular, until you tried to fire it. Just because the hammer would fall in dry-firing, didn't mean that the firing pin was going to set off the primer when the pistol had a round chambered. That right there put a lot of shooters off the design.

Colt wasn't making many commemoratives by the early 1990s, and those they were making were special-orders, but the urge was strong in many places. Colt just made what the customers wanted.

The Colt Series 80, with its internal firing pin block that some don't mind, and that others find a royal pain in the patootie.

As soon as there were other options for a 1911 pistol, the shooting world yawned at Colt's offerings. No one wanted the Series 80 thing, and there was even a com-pany that made a special plate to fill the gap in the frame once you had removed the Series 80 “firing pin malfunction inducer” parts. And this mattered big-time to Colt, because there was a new player in town.

In the late 1970s, a military surplus import/wholesale company by the name of Springfield Armory began. They focused first on the M-14 and made a product that was a semi-automatic-only copy: the M1A. Remember, this was when the .223 was considered “unmanly” and the M-16/AR-15 unreliable, inaccurate and soon to fade away. Target shooters still used the M14 on the firing line at Camp Perry then; heck, a lot were still using M1 Garands. (And the M14 would remain on top for almost another twenty years.) The first guns were built almost entirely with military surplus parts, on new, semiauto-only receivers.

In the early 1980s, they decided to go into the 1911 business. After all, why not? If your only competition is Colt, what's the problem? So they began to offer 1911A1s for sale. The first guns were pretty basic. In fact, they were USGI 1911A1s with a few extras, and shooters loved them. I was shooting in several indoor leagues by that time, and my prize for one of the leagues was a Springfield Armory 1911A1 parts kit: all the parts you needed for a complete pistol, just not assembled. By then I was an established gunsmith and had been working on 1911s for a few years. It took me all of half an hour to assemble that gun (everything fit correctly) and once together it worked 100%. I knew, as of that moment, that Colt was screwed.

And they were. The whole practical shooting universe was about to explode; the market for a 1911 (or 1911-like) pistol was going to go through the roof. And Colt was not going to get any of it.

The new entrant to the 1911 market was not just smart about guns, they were smart about marketing. Springfield jumped in with both feet on this new shooting sport and sponsored matches across the country. They also sponsored people, too. In short order, you could shoot any match of size, from a State championship, up to the Nationals, and win a Springfield 1911A1 as a prize. They also sponsored shooters. The first, biggest, and still the king of the hill, was Robbie Leatham. A kid from Arizona, working in a newspaper behind the scenes, he was to rocket onto the shooting scene. It took a couple of years for him to get a handle on this new thing, IPSC, but once he did, he essentially owned it. One big move that Springfield made was crown him the “Million Dollar Shooter.” They signed Robbie to a ten-year, $100,000 a year contract. In the late 1980s, that was more than just a lot of money, it was a watershed. It was an announcement that practical shooting was here to stay. (Just to give you an idea, in 2009 dollars that comes to $188,000 a year, and taxes were lower then, too.)

Another shooter Springfield picked up for a while was Jerry Barnhart. An ad Springfield used for a few years took advantage of their height difference: Jerry was about six inches shorter than Robbie. It featured Jerry, standing on an ammo crate, looking Robbie in the eye. They both had their arms crossed, and were giving each other a cold stare. The caption: “There's only one thing the two best shooters agree on.”

Poised to become the next professional sport, things didn't work out, for IPSC or most of the other practical shooting sports. Practical shooting was not able to make the next step: sponsorship by non-shooting companies. Why? My take on it was a combination of two things: One, it was just too outré for the Madison Avenue types. Running with guns? Heck, we don't even run with scissors. That, and the in-your-face defensive aspect of it, of shooting bad guys rather than waiting for the police, was just a bit too off-putting to the gatekeepers of greater success. Second, it just wasn't TV-accessible. The scoring system wasn't amenable to a “leader board” like golf, you couldn't see the bullet holes (either on the camera, or on the viewers' TVs) and the courses just didn't lend themselves to being videotaped. However, events like the Steel Challenge are much more TV-friendly, and they have had some success there.

Despite the lack of TV success, the shooting sports continued and Springfield expanded. They went from plainjane GI-type guns to special models and custom builds. The latest 1911 pistol is the EMP, which is and isn't a 1911. You see, the 1911 was designed around the .45 ACP, with a certain overall length. If you shoot a shorter cartridge, you need to use blocked magazines so the feeding geometry is correct. What Springfield did with the EMP was simple in concept, and difficult in execution: they took a 1911 apart, sliced it down the center of the mag well, shaved length off front to back, and put it back together again. Well, maybe the proof-of-concept gun was done that way, but the production guns were built with the intentionally shorter front-to-back mag well.

Robbie Leatham, doing what he does best, running a single stack 1911 better than anyone.

The Springfield EMP, first made to hold the .45 GAP, but since that cartridge shows no signs of taking over the world, the EMP is made in 9mm and .40. There, it excels.

Of course, this means shortening the slide in that area, along with firing pin, extractor, trigger (the bow needs shortening) and ejector. The result is a pistol with a magazine proportioned properly for a 9mm or .40 cartridge. The original intent was to make an ultra-compact pistol in the then-new Glock .45 GAP cartridge. However, that cartridge looks to be a dead-letter issue in any but a Glock pistol, and Springfield wisely ditched it in favor of the much more popular .40 and 9mm chamberings. As a super-compact little gun, the 9mm is a gem. The .40 is much more of a pro shooter's gun; the recoil can be quite sharp. Regardless of your choice, Springfield makes them and sells them like crazy.

A widely known secret is that Springfield 1911A1s are made on forgings from Brazil. The forgings come over with a certain amount of machining already done and finished up here in the States, where they're assembled and shipped. While the operation is subject to trade secrets and Springfield (justifiably) is reluctant to disclose things that might give their competition an advantage, I would surmise that how much machining is done in Brazil and how much is done here is more subject to political whims and exports regulations, than on rational manufacturing decisions.

One aspect of the Springfield 1911A1 that has changed over time is the shape of the frontstrap. The early guns are what are known as “fat frame” guns or “thick frame” guns. The radius of the 1911 on the frontstrap is supposed to have a common center. That is, the thickness of the front material is the same all the way across the front. On the early Springfields, the inner and outer radii did not have a common center. The outside was a larger radius, leaving the frame thicker at the outside edges. I found out, years later, why that had been: it seems that to make the machining faster (and thus less expensive) someone had decided to not have the underside of the front of the pistol machined in three radii: the dustcover, the triggerguard and the magwell frontstrap. Instead, a single-radius cutter was run along that line, cutting all three curves to the same radius. It took Spring-field a lot of wrangling to get the Brazilian maker to attend to that detail. Until then, a lot of gunsmiths (myself included) learned to grind and file the frontstrap radius to a “more correct” contour, prior to checkering, stippling or otherwise adding non-slip surface treatments.

In another part of the country, Cal Foster, an inventor and machinist, ran his own shop, taking custom orders from firearms manufacturers. Some of the parts in firearms of the 1970s were “fabbed up” by Cal and his machine shop. Wanting to offer more, Cal formed Caspian arms and in the early 1980s began to offer what the 1911 world had wished for for a long time but had not had: a source of parts not dependent on Colt or military surplus. You could order up a slide or frame any way you wanted, provided Caspian could make it. I was a new gunsmith then, and I ordered up and built a lot of one-offs and custom guns based on Caspian parts.

One of the ones Caspian made (but which I never owned, alas) is odd in the extreme: the Randall left-handed 1911. I'll let Gary Smith, Sales Manager and long-time employee at Caspian, explain:

Well, here's the story. Back in the 80s we made stainless steel left-handed frames and slides for Randall along with some other small parts. They were totally mirrorimage 45s down to the rifling. After Randall went out of business we found ourselves with a small inventory of left hand parts. Amy, our Vice President, had gone on a scavengerhunt for many years to find enough left-hand parts to complete the pistols we still had. She finally rounded up enough components to make some pistols for the shop as well as twenty complete sets to sell to the public. These parts kits were serialized LH 1 OF 20, etc. We still have a mish-mash of parts in inventoryand are still searching. An interesting footnote is that Storm Lake Machine recently made up some left hand barrels to complete the kits.

That's right, a left-handed 1911, from mag button to ejection port, and rifling that pitches the wrong way. You of course need a left-handed magazine, because otherwise the mag catch slot is on the wrong side. And if you have a left-hander and need parts, Caspian just might have them.

The big news in 1983 was the fact that you could have a stainless steel 1911 that wasn't a Colt. While not the first to offer an all-stainless gun (AMT did that back in the late 1970s) Randall's entering the market made it clear that Colt was not tending to its customer's needs or desires.

Caspian does custom serial numbers; they make the parts pretty much the way you want them. They just don't assemble the parts you order. You'll have to find someone else to do that.

One of the twenty left-handed Caspians, built and customized by Rich Dettlehouser. Photo courtesy Rich Dettlehouser

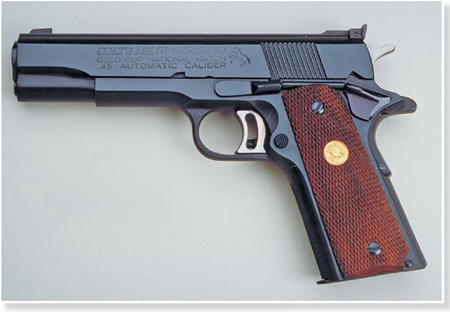

Mk IV Series 70 Gold Cup National Match.

A whole lot of other-name 1911s, some from well-known 'smiths and companies (at least in the early days) were actually Caspian 1911s. The process is called a “marking variance.” Federal regulations require a manufacturer to put their name and the city they are located in on each firearm receiver they make. You can, however, request a variance from the BATFE. You simply send in the paperwork (“you” as in a company wanting to make 1911 under your own name) and the BATFE approves it. Then, on the guns you have pre-ordered from Caspian, once the variance is approved, they mark your name and city, and the serial number sequence you desire, on the receivers so ordered.

There is a very good chance that if you own a 1911 made by a company that was in business for only a short period of time, it was really based on Caspianmade parts.

Caspian still makes custom parts, and if you simply have to have a six-inch slide in 10mm with your name engraved on it, you can get it from them. One thing Caspian also offers (although it depends on the material supplier) is Damascus steel slides. Incredibly expensive, and ferociously dulling on cutting tools, Damascus is the figured steel you see on expensive period sword blades and on some high-end modern custom knife blades. Does it offer an operational advantage over carbon or stainless steel? No, but it looks different, and for some that is more than enough. The danger of Caspian is the same as the danger of Brownells, the famous gunsmithing parts and tools catalog: they can easily melt your credit card.

Jump ahead twenty years, and we find the world an entirely different place. So many people are making 1911s it is difficult to keep track. Each year at the SHOT show (the annual dealers/writers/whole-salers/manufacturers trade show) I see more and more people who are making 1911s. More than one wag has noted that if this keeps up, “in the year 2025, the only guns anyone will be making will be Glocks and Glock-like polymer guns, 1911s, cowboy guns and AR-15s.” The share of guns Colt makes is smaller every year.

Back in the early 1980s, before the change, the market for 1911s probably was not much more than 50,000 a year. Once the IPSC train got up and rolling, the market expanded to 100,000 guns a year and even more some years, and has stayed there for a couple of decades or so. In that time, the Colt total, not just share, has shrunk. Colt barely makes the top twenty-five firearms manufacturers today, and their total annual 1911 production is well under 20,000. Now, a lot of their apparently low numbers are due to making M4s for the government. Those don't get counted, since we can't buy them. So, if you were to add in the hundreds of thousands of M4s they make each year, Colt would be near the top. But this is about 1911s, and they don't make many. However, things are looking up. Colt is offering a new Series 70, with a solid bushing and no Series 80 firing pin lock. They are offering WWI and WWII-era Colt copies, solid guns to build or use as-is.

To see what was up, I visited Colt, at the new/old plant.

Stopping in at Colt is not like drifting into the local museum just to see what's new. In fact, getting into Colt at all is difficult, as they are a primary source of military firearms, primarily the M4. Just getting in requires an invitation (don't ask; few get them) and a chaperone. In walking around Colt, you pass piles and bins of stuff devoted to military contracts. Despite the fact that almost all the parts that are in the M4 are the same parts found in the Colt semi-auto models, the government has no sense of humor about people peering at government parts.

So what you see herein are not the photos I took, but the photos Colt took, with me walking through, pointing and commenting. That is, the photos that passed the multiple layers of security: the government, the production staff, the company lawyers, and the postal service.

Also, in walking through Colt, you are not walking the same paths taken by Samuel Colt, or John Moses Browning. That would be the old plant, the “Onion Dome” building. No, the old plant proved to be too old decades ago, and Colt had to move out. The old plant now sits, empty, right next to I-95. The old plant was the subject of some discussion and planning to turn it into condos, but the cheerful banners announcing the redevelopment are now faded and quite depressing. When I went by the old plant, I had gotten directions from the staff at the Connecticut State Library. One of the guards, on hearing my repeat of his direction, asked “You aren't going to walk, are you?” I paused for a moment, and then asked “Because of weather [it was a bit hot that day] or safety?”

“Well, safety. You go through a bad neighborhood to get to the old plant.”

My reply: “Hey, I'm from Detroit. How bad can it be?”

“Oh, you'll be all right then, but keep the camera out of sight.”

Colt Gunsite Pistol.

Now, in many places I've gotten much the same sort of warning: That's a bad neighborhood, you don't want to go there. Advice I find kind of quaint. I mean, outside of a very few places, such as the South Bronx, Southside Chicago or South Central L.A., there aren't many places as bad as the bad places of Detroit. Not that I say that with any pride, mind you. But for a long time Detroit was Beirut without the RPGs. The “bad” parts of Hartford are simply a bit shabby, comparatively. The old building is impressive, and had to be even moreso in its original days. Now, Colt is in a modern industrial building, with everything on one level.

Commander in .38 Super.

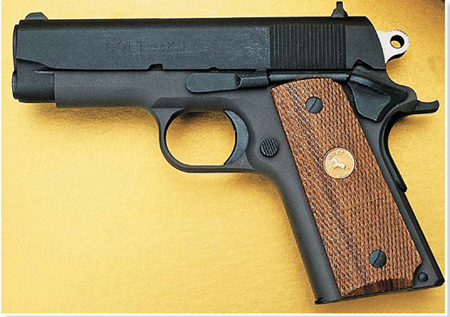

Pre-Series 70 Com-mander.

Once I passed through security and had donned my protective glasses, the plant was, well, a manufacturing plant. Noisy machines, the smell of oil, aisles with painted sidelines, to indicate safety limits and area designations, posters, drums of scrap metal and tables and workbenches. And machines making parts, with stations of workers testing, inspecting, or assembling firearms. But in all that, 1911s are being made. Until recently, Colt had been in the unenviable position of still using large numbers of individual machines to make parts. On my visit, they were replacing a whole wing of individual machines with brand-new multi-axis OKK machines, to make slides. Instead of dozens of mills, they will be able to run two shifts of slide-making a day.

A slide, which takes 320 machine operations and formerly had to be done on nearly a hundred different mills, is now done by a single machine, one that swaps tools, tracks tool wear, checks dimensions, and never mis-reads a dimensional readout. Also, changing slide lengths, configurations or calibers is as simple as loading the correct forgings and the appropriate cutting data file.

So Colt will be able to increase production and be more flexible in model offerings. With the machines I saw, and more coming, they will be able to switch models overnight, even from one shift to the next, instead of the days it used to take.

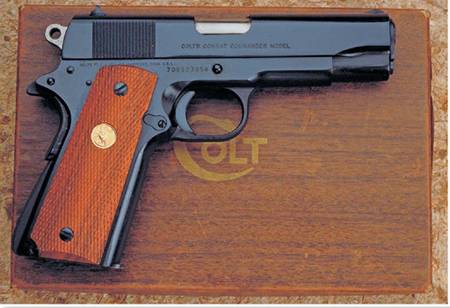

Combat Commander, nickel finish.

Combat Commander, blued finish.

That, however, does not mean an end to some of the old practices. For one, the parts will still be made from forgings. Colt has always made 1911s from forgings, specifically the frame, slide, barrel and slide stop. That's right, the slide stop is a forging. Other parts are made from billet, such as ejectors. Despite the emphasis on modernizing, there are still steps that are done by hand. (And would you expect anything else from a company with the history of Colt?)

Colt Government Model 1991A1.

The magazine wells are just one area that receives hand attention. The operator at that station fits five new frames together and clamps them in his vise. Then he takes specially-sized files and cleans the tool marks off the interior surfaces and deburrs the edges. That kind of attention to detail was evident at every workstation. The work went smoothly, without hurry, and every edge and surface was inspected once it had received the attentions of his file. I wondered, as I walked off, how long a file lasts? I didn't have the chance to ask, because by the time I had formed the question, we were on to the next station and the next fascinating process.

1991A1, stainless finish.

At one point, while we were admiring bins full of raw forgings, long-time employee Dominic Montessori stopped by. OK, we've all learned things about the 1911, usually by reading about it or talking to other shooters. It turns out that there is a whole other language in the Colt plant, with a vocabulary we have to learn. If you have a slide in hand, look at it. Otherwise, look at the breechface in your mind's eye. The sidewall of the breechface, opposite the extractor? That surface is the “J cut.” I worked on that surface for years when I was gunsmithing and no one ever called it that. The machine that makes that cut is a fascinating one, and one that will not be replaced by a CNC machine. You see, the machine that makes that cut works faster than a CNC machine would, and with an experienced operator it does not produce bad slides. So it will remain in use for the foreseeable future.

Mk IV Series 80 Officer's ACP.

Another machine that will remain, Dominic told me, is the machine that cuts the trigger bow slots in the frame. Colt still uses the machine they bought in 1913 to make those cuts. Why? Again, it makes the cuts with clean corners, and it more than keeps up with the CNC machine output.

While Dominic and I were talking, he had finish-machined slides and frames to show the weight differences between forgings and finished. He slid the slide onto the frame, and I was pleasantly surprised to see the slide stop, 3/8 of an inch short of the frame back. That's right, readers. Colt, with the new machines, is now going to be making slide-to-frame fits that have to be finish-lapped to fit. No more of the old guns that rattled when new. And good news for custom gunsmiths. Many of the name 'smiths prefer to work on Colts.

You see, there are a number of top-end custom gunsmiths who prefer to, or will only work on, Colt pistols, partly because of the forged parts, partly due to better quality, and partly due to economics. After all, if you're quoting someone $2-3-4,000 for a full-house gun, the customer will be happier if the name on it is Colt.

The polishing department is filled with machines purchased decades ago from Hammond, in Kalamazoo, Michigan. Each requires an experienced operator, as there are some things a machine just can't do. Each buffing/polishing station requires a different grit, a different wheel or flat-backed loop, and each operation requires a different technique to produce a correct polish.

Meanwhile, ejectors are roughed-out from their billet form on a single machine. The operator takes nine blanks, fits them in the vise, and taps them level. The machine cuts the bottoms, roughing the posts for the ejector legs. Once cut, out they go and nine more in a block go in. Then it is off to the keyholing cuts, and finally the rounding of the posts.

Barrel forgings are first rough-cut on the bottom lugs, then drilled through. They get drilled, reamed, lapped, then broached (cutting, not buttoning) before they see the CNC profiler. That machine then cuts all the exterior surfaces, including the locking lugs and chamber. And then, barrels get another step: they are proofed outside of the gun. Each one goes into a fixture that holds it in place, and a breechblock closes behind it. Then Henry, the operator, fires a proof round in each barrel. So, even if you buy a replacement Colt barrel, it has been proofed.

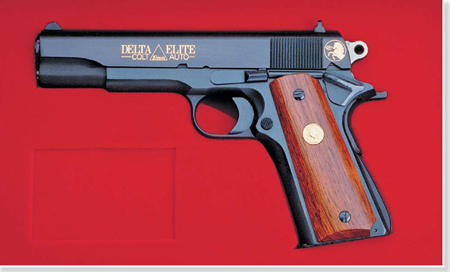

Delta Elite.

Once all the parts have been made, they get assembled. The assembly cell is separate from the manufacturing cell, and each assembler works on one area. I watched the installation of plunger tubes, and the operator was using a set of pliers with a compound linkage, to crimp the plunger tube legs in the frame. “Better than power, you can feel it set home.” You of course would be illadvised to get in a hand-shaking contest with someone at Colt who has worked that station.

Assembled, inspected, now they get test-fired for function. Each Colt 1911 gets five rounds; two hollowpoints and three ball rounds, and if they don't pass they get sent back. Then, it's scrub, box, label and ship.

You'd think, in the early years of the 21st century, that everything would be made by machine. Clearly not, and we are the better for it.

Hypothetical question: What if Colt had had an awakening in the early 1970s? With the collet bushing not well-received, what if they had decided to take the QC problem head-on? They could have prevented many of their eventual competitors from entering the 1911 field and thus kept a larger share of it for themselves.

Alas, it could never really have happened thus. By 1970 Colt was totally in thrall to one or another corporate conglomerate. (In 1970 Colt was a small division of a heavy-equipment manufacturing company. The parent company made machines bigger than the machines Colt used to make its product.) They were also making the parent company a ton of money on M16 contracts, with little or no need for upgrades, equipment or product.

No, best to simply let the curtain gently fall back across what might have been, for it is so unlikely that it would not even qualify as science fiction.