CHAPTER 3

THE TRIALS OF THE CENTURY

When it came time to adopt a new pistol, the US Army went about it in an eminently reasonable fashion: they held a contest. They told those who wanted to enter, “This is what we want” and then “This is what we'll do to it.” When they had enough prospective models to try, they arranged for everyone who could to be there, thrashed the sample guns, and afterwards told each what was wrong, what broke, etc. They then told those who wished to continue, “Come back with improved pistols, and we'll do it all over again.”

This was such an eminently practical model that the government got away from doing things that way just as quickly as possible.

Now, the Army had been testing pistols for the entire first decade of the 20th century. The usual explanation is the experience of the US Army in the Philippines, where it faced the Moro tribesmen. Typically, those slightly-built combatants would soak up multiple hits from the then-issue .38 Colt revolvers, and still whack people with their sharp machetes. That the .38 Colt was underpowered is not debated. A 150-grain lead round noise bullet at an uninspiring (and probably factory-inflated) 755 fps, it was typically loaded with black powder at the time of the Philippine fracas. When the bad guys didn't fall down fast enough, Colt 1873 revolvers were hastily re-issued, and performed well.

When the bad guys didn't fall down fast enough, Colt 1873 revolvers were hastily re-issued, and performed well.

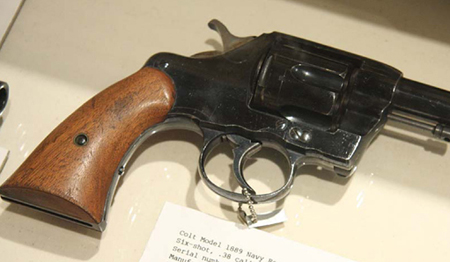

This is an 1889 Navy Model, a .38 Colt revolver such as was used in the Philippines. This was also the first successful double action revolver with a swing-out cylinder.

Before we go and heap all the blame on the little .38 (of which a goodly portion it certainly deserves) let's consider the dynamics of the situation: someone running at you, screaming, waving a big, sharp knife. Armed with a .38 double action revolver, you're going to empty the pistol of all six charges, and perhaps hit with some or all. Will they be solid, center hits? Unknown; probably not. At least some were. I've read reports from the scene of Moros taking five and six hits — but all peripherals: arms, flanks, edge hits — and surviving. I mean, when you see a photograph of a Moro sitting for the camera, pointing to his bullet wounds, you know they weren't center hits. Now, change the sidearm to a single-action revolver. You're only going to be able to get one shot off before the bad guy closes with you. What are the chances that you'll bear down, use the sights, and make sure that your one-and-only shot centerpunches the little dude? That dynamic alone increases the observed efficiency of the .45 versus that of the double action .38.

Add to that the disdain in cavalry circles with the puny little service revolver, and it is no wonder the drumbeat was “.45” for a decade.

Not that the Army didn't look at alternatives. In 1900 they placed an order with Deutsche Waffen und Fabriken Munitions for 1,000 Lugers, for test and evaluation. They acquire holsters, spare magazines, and ammunition and issued the pistols to selected cavalry troops across the United States. The commanding officers issued the pistols, and tracked their use, malfunctions, etc. Generally, the pistols worked well. There was some concern that the troops might have found find a self-loading pistol a bit too complicated, and there were maintenance issues, but overall, the test was positive and paved the way to the adoption of a self-loading pistol for general issue.

An M-1900 Luger Army Trials pistol in .30 Luger.

Meanwhile, Colt was making first the M-1900, and then the M-1902. The Army bought batches of those for testing, too. Large pistols, chambered in .38 Auto, they worked quite well. The idea of autoloading pistols still being quite new, Colt and Browning still had a lot of details to work out, things like safeties, magazine release location and function, slide stops (should it lock open when empty or not?)and capacity.

At first glance, the M-1900 .38 Auto seems just a bit odd. Look deeper and it gets odder. First, there are links under the barrel, both front and back. When the barrel swings down to unlock, it does not tilt. It simply swings down parallel to where it was before. As a design it is very cool. It removes the need for a bushing, and barrel fit can simply be the barrel propped between the swing-up pin and the inside top of the slide. The drawback is the assembly: there's a cross-bar at the front to keep the spring and guides in and the slide on. If the slot where the cross bar cracks and breaks off, the slide may exit to the rear. Now, in all the years of reading about guns I've never read of that actually happening. I imagine it seemed like a big deal in 1929, with the unveiling of the .38 Super. Using the same case dimensions, the Super fired a 130-grain bullet at 1300 fps, compared to the M-1900 and its 130-grainer at 1050 fps.

That the M-1900 would snap like a twig at the difference seems unlikely, Still, I'm not willing to test that, at least not with my own two hands and a firearm I own. Now, if a police department with a confiscated M-1900 slated for the smelter is willing to let me clamp it in my Ransom rest for some testing, I'll be eager to report back.

The early Colts (this is a Model 1903 Pocket Hammer) all had the wedge out front. If the wedge came loose, or the slide broke, you were in a world of hurt.

As noted, the original M-1900 design had a “rear sight” safety. The rear sight moved, and by pushing it up or down you could safe or ready the pistol for firing. Besides being less than sturdy, the design required rear sight movements, which were not good for accurate aiming.

The slide stop was a small tab on the left side, just ahead of the grip panel. It the magazine was empty and could be pressed down to release the slide. Other than being small, it was entirely sufficient. The magazine catch was dead-simple: a pivoting lever at the bottom rear of the magazine well. It hinged forward and latched into a crossways slot in the spine of the magazine. To release the magazine, you simply squeezed your hand closed at the bottom rear of the magazine well. This pinched the lever to release the magazine, and positioned your hand to catch the magazine as it came out. In a characteristic bit of cleverness, Browning made the trigger return spring do double-duty: above its attachment point it returned the trigger. Below, it actuated the magazine catch.

However, this was more than half a century before IPSC and the idea of dumping empty magazines willy-nilly to maintain volume of fire. A magazine was a rare and valuable thing, and you needed it later. (An attitude that has continued in the military up to this day.) So a thumb-button magazine was not a high priority. Luckily for us, the Army saw things differently.

The magazine catch was dead-simple: a pivoting lever at the bottom rear of the magazine well. It hinged forward and latched into a crossways slot in the spine of the magazine.

The M-1900 was an unfinished pistol, a work in progress, but it showed the future. It also gave clear signs of its shortcomings. In researching this book, I've run into a number of tales. One concerns John Moses Browning in the early development of the M-1900 pistol. Having made another prototype, Browning went to test-fire it. The test-fire ranges being full of production work, he hiked out to the Connecticut River with the pistol and a supply of ammo. There, he test-fired it into the banks of the river. So there Browning away, watching the is, blasting away, watching the pistol, its function, and probably the ejection pattern, when the slide breaks off and goes zipping past his head.

The Colt Model 1900 (this is serial #141) was a huge advance and a fragile pistol.

Whether it happened or not, the M-1900 has always had a reputation for fragility, and that fragility could only have been a spur to further design, testing and development by Browning. It is apparently pretty common in the collector's world to find M-1900, 1902, 1903 Hammer and 1905 pistols with cracked slides. Some collectors even work to acquire pistols with pre-war frames, and post-war slides, as those were clearly pistols that had suffered a cracked slide and had to be re-built at the factory. Sort of like the Glock collectors who seek out “Factory mis-match” guns: Glocks in which someone blew up the slide or barrel and had it factory repaired.

They used pistols in calibers from .30 Luger up to .476 Colt, from a 93-grain bullet at (a listed, and hopelessly optimistic) 1420 fps to a 288-grain bullet at 729 fps.

Now, not everyone was willing to simply adopt a Browning locked-breech pistol. A lot of countries still figured a blowback would do fine. Who needed a lot of recoil and power? As a result, we had countries adopting Browning designs like the M-1903 and copies of Browning designs. It was not uncommon for armies of the world to adopt .32 and .380 pistols when they switched from revolvers. You know, I can't imagine what would be going through the mind of an Infantry officer, contemplating the .32 his country had issued him, and what the heck good it was going to do him if his unit was about to be overrun.

The US Army still hadn't decided what they wanted. They hadn't even determined the caliber. To get some info on that, two officers — infantry Colonel Thompson and Medical Corps Major LaGarde — were tasked with finding out. It is popular today to be a bit scornful of the Thompson-LaGarde tests. After all, they didn't do things in a thorough and scientific method. Me, I reserve my scorn for the 1980s 9mm trials, where great effort was put into properly formulating a lab-grade formula for mud, when the results were probably even more predetermined than that of the Thompson-LaGarde tests.

As everyone knows, during the Thompson-LaGarde tests they fired on a dozen slaughterhouse animals, testing various calibers. However, they also fired on suspended cadavers, noting the movement of the body or the limbs to bullet impact. Yes, they were using corpses as ballistic pendulums. They used pistols in calibers from .30 Luger up to .476 Colt, from a 93-grain bullet at (a listed, and hopelessly optimistic) 1420 fps to a 288-grain bullet at 729 fps. The results and the report were favorable toward large-bore handguns, and so the recommendation was that the Army adopt a pistol not less than .45 in caliber.

This put Colt and Browning in a spot. Their pistol was in .38. Undaunted, they acquired a supply of the current .45 ammunition.

Today we tend to view the 1911 as a given; we also assume the ammo was a given, too. Such was not the case. The Army, through the Frankford Arsenal, kept fiddling with the case length, bullet weight and shape, and velocity. You could be working on a pistol and find that the next change wouldn't work in yours, and you'd have to figure out why. No wonder Georg Luger had fits, getting his design to work with American ammunition.

Browning quickly made a .45 prototype of the M-1900 in .45, and broke it even faster than he had the .38s. A brief aside here. Doing research for the book, I visited the Connecticut State Library, which has a display of early Colt firearms. (No kidding, a library with a gun collection.) In it, there is a Colt M-1902 Military Model that clearly shows that Colt and Browning were anticipating the Army requirement. It is a 1902 Military Model, but it is rollmarked “Model of 1903” and it is chambered in .41. Which .41? Bore diameter, case length, velocity? No one knows. But Browning was clearly looking to move up in terms of caliber.

The .45 in the M-1900, known as the M-1905, had problems that needed to be solved. Browning found the more robust cartridge created a downlink speed and force greater than his links could take. So, he added underlugs. The underlugs struck recesses in the frame, halting the barrel progress before the impact could be taken up by the links. Thus, for a time, he was able to offset the weakness of his initial design.

The mystery Colt. A Military Model 1902, marked “Model of 1903” and chambered in .41.

The marking is not an overstamp, nor an error on the part of the curator.

Shoulder stocks were all the rage on pistols a century-plus ago. This is the stock/holster for the M-1905 commercial pistol.

The first Browning M-1905 military prototype, an enclosed-hammer model. The Army didn't like that, so John M. Browning exposed the hammer for them.

You can see that John Moses had some new ideas. Notice that on this M-1905 proto-type, the slide stop is on the right side.

The M-1905 sold reasonably well, more for its caliber than the strengths of the design itself. As was the taste in the period, it was offered with a holster/ shoulder stock, so you could use it as an impromptu carbine.

In the 1907 pistol trials, it was neck-and-neck between the Savage and Colt pistols. In fact, the Savage beat the Colt in the dust test and was not far behind in the rust test.

Having tested various commercially-available pistols for the first few years of the decade, the Army was ready to conduct some head-to-head tests. The organizers of the first test, the planned-to-be-1906 test that actually ended up happening in 1907, invited a whole slew of manufacturers, but only a small number of them had something to offer and brought or sent it. These were Colt, Savage, DWM, White-Merrill, Knoble, Bergmann, and Webley. Only the Colt, Savage and DWM designs were considered far enough along to spend time with. The rest were politely told their products were not up to the tests to come. Planned for September of 1906, the trials began in January of 1907.

Let's take a look at the subjects of that exam.

In the 1907 pistol trials, it was neck-and-neck between the Savage and Colt pistols. In fact, the Savage beat the Colt in the dust test and was not far behind in the rust test. The Luger was well behind both of them in both tests, suffering particularly badly in the rust test.

Before we get too far into the test, let's take a walk around the Savage, and kick the tires and look under the hood. I had the great fortune to connect with a collector who has not one, or even two, but four of the field trials Savages from the contract that was let after the 1907 armory trials. He had a fifth at one time, but sold it. (“I wish I hadn't,” he said, to no great surprise.)

Keep in mind that the pistols we're looking at, Savage and Colt, are the “field trials” guns, not the armory trials guns. The armory trials guns were true one-offs, handbuilt in extremely small lots, while field trials guns were built in greater number and issued for further testing. While the field trials guns are rare, the armory trials guns are truly unique.

The Savage M-1907 field trials pistol, an eight-shot .45 ACP pistol.

The thumb safety pivots at the front, and is not very ergonomic to use. I suppose with time you could get used to it.

The Savage M-1907 in .45 is a single action pistol with a thumb safety and grip safety. It is a locked-breech design using a rotating barrel, and feeds the rounds out of a semi-kindasorta double stack magazine. The controls are not where we expect them to be. The thumb safety pivots on the front, so you use the base of your thumb to rotate the safety lever. The grip safety is up at the web of your hand and is pressed straight into the frame. This is actually a good thing, as I cannot see how anyone could fail to depress it. Those of you who have the problem of a too-high grip that fails to fully depress the grip safety on a 1911 would find the Savage a lot more amenable. However, that plus is offset by the design, which is a curved paddle raised above the rear of the frame. It is possible for stuff to get under the paddle and thus prevent the grip safety from being depressed.

An interesting design element of the Savage is its rear sight: it doubles as the extractor. The sight and extractor are a single piece of steel that simply rests in a recess in the underside of the slide top. At the rear, the sight pokes through a rectangular slot, and up front, the forward tab is the extractor hook. It also cams up, when there is a round in the chamber, so you can feel the extractor. Yes, a loaded chamber indicator, circa 1907. Even while I was admiring it, I could see all kinds of problems. First of all, nothing holds it in place except the cocking piece assembly. It falls out when you take the pistol apart, and it can easily become lost. Also, the rectangular slot for the rear sight is a stress point. I can predict that if the Savage made it to production, the rectangular slot would be the point of origin for many a slide crack.

The magazine catch is in the front of the frame, at the bottom, and recessed into the magazine well boss. To drop the mag, you have to use your pinkie finger. The slide stop is a deeply recessed lever on the right side of the frame, behind the trigger. To lock the slide open, you have to hold the slide back and use your trigger finger. But you have to press straight up towards the slide, an awkward movement. To fill out the list of non-ergonomic features, the grip angle is the same, too-right-angle that many pistols of the period had.

The Savage's grip safety is much better than the Colt's in ease of being depressed, but it has a gap under it where crud and debris can collect.

As an area of study, ergonomics was just getting started in the first decade of the 20th century, so it should not come as a surprise that early designs might be a bit awkward. After all, if the first step is coming up with a reliable and durable design, you follow what works. Then, once you have it working, you adjust to make it fit the worker — in this case, the soldier.

The Savage's extractor is also the rear sight and the loaded chamber indicator. And, as a loose part, it's something I can see being easily lost in cleaning.

The magazine catch is small, recessed, not easily used, and cleverly kept out of harm's way.

The slide stop is even more awkward to use than the mag catch, but you can always just yank back on the breechblock and “slingshot” the pistol closed.

What looks like a hammer is simply the cocking piece indicator.

The Savage has what looks like a hammer, but is simply the cocking indicator for the striker. Not a striker as we now know it, for the Savage was not a Safe Action kind of design. When the slide cycled, the bottom of the striker indicator bore against the inside curve of the rear of the frame. The bottom of the striker indicator was pushed forward, and thus when pivoted it drew the striker back. Once the striker went back far enough to clear the sear, it was fully cocked and remained so when the slide returned. Meanwhile, the trigger bar had been depressed as the slide cycled, taking it out of line with the sear. When you released the trigger, it moved forward, and the trigger bar popped up in line with the sear. When you next pressed the trigger, it bore on the sear, cammed it out of the way of the striker, and you fired the pistol again.

To disassemble the Savage, you have to hold the slide halfway open. At fully closed, or at fully open, the cocking assembly is kept from rotating. But in between, there is a spot where you can pinch the cocking indicator between your thumb and forefinger and give the assembly a half-turn. In that regard it and what follows is exactly like the .32 and .380 pistols. Once the cocking assembly is out, release the slide and ease it forward off the frame. The trigger assembly wants to do a backflip and disassemble itself when the slide comes off, but it is easy to push back into place.

However, the trickiest part of the Savage is the lanyard loop. What, you've never seen a photograph of a Savage .45 with a lanyard loop? That's probably because all the photos you've ever seen are the same photo, copied repeatedly. What you're seeing here are probably the first new photographs of a Savage .45 in the last few decades, perhaps half a century.

The lanyard loop is hinged up into the magazine well. What looks like the main-spring housing pin is the lanyard pivot pin. If you want a lanyard loop, drop the magazine, reach into the mag well with the tip of your little finger, and pivot it down, Re-insert the mag, you're done. No loop? Drop the mag, push the loop back into the frame, re-insert the mag. In either position the magazine keeps the loop from pivoting out of place. And if, during a mag change, the lanyard loop should move a bit, the magazine will body-block it back to where it belongs.

The Savage takes a bit of getting used to in order to disassemble it, but you get better with practice.

All in all, it's a relatively simple design, as gas-era designs go. However, it was much more complex than the Browning design, which would doom it in the future.

The lanyard loop out

The lanyard loop being pivoted in or out.

The lanyardard loop, stored out of the way

What caused problems at the time was the Savage's locking design. The barrel was made to rotate. It had two lugs on it: the bottom one rode in a slot in the frame, and the slot allowed the barrel to rotate. The top lug rode in a cam slot in the slide, and the dogleg in the cam slot is what rotated the barrel. The rotating barrel has always had a certain fascination for some designers. In the mechanical engineering world, it is the equivalent of a “wet paint” sign. Some designers just can't stay away from it. In theory, it is fine. The idea is simple: you use the twist of the rifling as a means of pre-loading the barrel against unlocking. If I may coin a seriously ugly term of art, the “dynamic inertia” of the bullet's being forced to rotate delays the rotation of the barrel in unlocking. The idea is appealing but seems to not be nearly as effective as its advocates would claim. At least not then, anyway.

The test-firers of the time remarked on the recoil of the Savage. Now, when a group of full-time shooters, who test-fire pistols on a regular basis, note that one model has markedly greater recoil than another, there has to be something there. One tester remarked that he'd “rather shoot two thousand rounds from the Colt, than 500 from the Savage.”

If I may coin a seriously ugly term of art, the dynamic inertia” of the bullet's being forced to rotate delays the rotation of the barrel in unlocking.

Ouch. I asked the owner of these pistols if he'd ever fired them, and what his impression as. “Not a problem, they kick about the same as the Colts.” Now, I've had occasion to fire rotating-barrel pistols. I own a bunch of Savage .32 and .380 pistols. As pocket pistols go, they are not any less snappy in recoil than their blowback brethren. I've fired the MAB-15, a French 9mm from the 1960s. It is an all-steel, high capacity 9mm, and as such it is one portly beast. It weighs more than a 1911A1 Government model, and despite the 9mm chambering, kicks worse.

The cam slot in the slide of the Savage. The rotating barrel design is like catnip to some designers.

Here is one of the Colt M1907 field trials pistols, #16. The grip is nicely-shaped but oddly-angled.

Why the harsh recoil? Simple: there is no pre-unlock dwell time with a rotating barrel. As soon as the slide begins moving on the Savage, it is rotating the barrel. So, very little of the initial recoil force is soaked up by the act of unlocking. On the 1911, the slide and barrel move together for a short distance before the barrel is linked down out of the way. During that short time, the recoil forces are exerted on both the mass of the slide and the barrel. On the Savage, the recoil force is exerted on the slide and is used to rotate the barrel. Rotational friction is much less effective.

The Colt offering was a pair of M-1905 pistols. They were only slightly changed from production models. The field trials guns were upgraded to include a loaded chamber indicator, and while they had a grip safety they lacked a thumb safety. Apparently, the grip safety requirement was a new one. I can well imagine that the cavalry officers would insist on such a thing. Whether the idea was to produce a pistol that was actually safe, or simply a matter of the old cavalry hands putting their foot down (and attempting to quash this pistol idea), who knows, but it seems prudent. After all, if a cavalry trooper dropped his pistol, things were bad enough in a melee without it discharging when it hit the ground, or repeatedly discharging as it jounced around at the end of the lanyard. The sample pistols I was able to handle and photograph are in the collection of Wayne Novak, the well-known 1911 pistolsmith and sight designer. I asked Wayne why the loaded chamber indicator was missing. “They all came out in the tests,” he answered. I guess the Army figured that they didn't really need one all that much and didn't insist on one for the 1910/11 trials.

The 1907 had the same wedge in the front of the slide as the 1900-1905 models had.

The Army insisted on a lanyard loop, so Colt simply shortened the grip and stapled a ring to the side of the frame.

The slide stop was a fitted slider, not a pivoting lever. At least it was where you could use it.

The grip angle on the M1907 Colt was the same as that of the M1905. To our modern, 1911-centric tastes it is a bit too right angle. But not so much that it would be objectionable to use.

The third entrant in the 1907 trials was DWM's Luger pistol. The Luger had been the darling of Europe already by then. It had been adopted by the Swiss and the German Navy. The German Army was ready to adopt it, as soon as all the bugs were worked out of the 9mm cartridge to their satisfaction. The Luger had not been bought by the French, but then I can't imagine either the Germans offering it, or the French accepting it. In that time period, the French would rather have gone to war with sharp sticks than use anything German. But the US Army wasn't interested in 9mm. They wanted a .45 pistol. So, reluctantly, Georg Luger designed and built a .45. In the summer of 1906, Frankford Arsenal shipped 5,000 rounds of the ammunition to be used in the tests to DWM. By February, two sample pistols were forwarded to the US army for testing. It is unknown how many were made in total, perhaps three or four, perhaps six or eight. Serial #1 was pretty much used up in testing, and no one knows what happened to it. (Probably unceremoniously pitched into the trash, when the tests were done.) Number 2 remained at Springfield Armory until after WWII, when it was sold to collector Sid Aberman.

The test results were not encouraging. The Luger suffered badly in the dust and rust tests. Clearly, with two hand-built prototypes, there wasn't any chance to test parts interchangeability. The Frank-ford Arsenal ammunition and the Luger hadn't gotten along well, and the Army gave DWM permission to use their own ammunition. It still wasn't all that reliable.

Despite their recoil, the Savage pistols worked well, shot accurately, and scored well in the tests, compared to the Colt. So the Army, being the thorough and conservative organization that it was (and still is), asked for more testing.

They extended a contract each to Colt, DWM and Savage for 200 test pistols. The Army wanted to take the nearly-finished but not yet debugged designs and issue the pistols to units in the field. There, they would get feedback on what worked, what didn't, what the troops liked or disliked, and what was prone to breakage. Meanwhile, the two were asked to go back to the drawing boards, improve the shortcomings, and come up with better guns for the next round of trials.

You might ask why field trials? Why not simply continue armory, or laboratory tests? Simple: as much as I favor the scientific method and extol its virtues, there are things the lab can't test. The firearms trainer John Farnam once put it best: “You can lock two Marines in a bare room, each with a ball bearing. Come back in fifteen minutes; one ball bearing will be missing, the other broken, and neither Marine will know what happened.”

The Army simply wanted to subject the prospective new pistols to the same environment that the current pistols had been undergoing during their service.

The reactions of the three companies could hardly have been more different. We look at both Colt and Savage as respectable old companies, with rich traditions of design and manufacture. DWM is the exemplar of an old-school European firearms manufacturer. But in the 1900s, that wasn't the case. The Savage company was new. They made rifles, in particular the Model 1899 lever action. It was the personification of modern: sleek, slim, and with significant advances in design. The rotary magazine meant shooters could use ammo with the new pointed bullets. The '99 had a solid lock-up, and could be chambered in higher-pressure rounds than other lever-action rifles. They took advantage of that in the coming decades, much to the chagrin of Winchester.

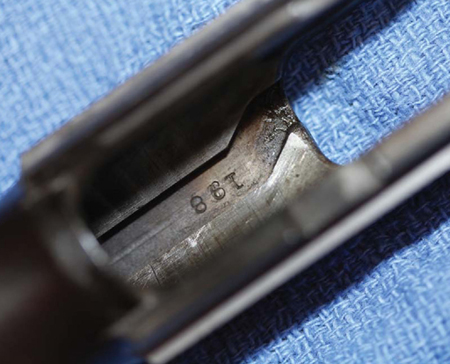

A rare pistol, with a low serial number and the inspector's initials below it.

The Army wanted a grip safety, so Browning designed and installed one.

The missing loaded chamber indicator. Apparently few remained in the pistols after a while in the field and being shot a bit.

You can see below the barrel the arresting slots Browning had to put into the M-1905/7 to make it able to stand up to the .45 cartridge.

The slide and wedge, removed from the pistol. That's all that keeps the slide from coming off the rear and toward you.

Colt at the time was suffering from a shortage of product. Their bread and butter had been the Single Action Army, which was clearly going to be toast as soon as the tests were done. The New Service was selling well, but it, along with all other double action revolver designs, had a clearly limited life, what with the Army going to pistols. Their rifle and shotgun lines were slow sellers. Colt had bet the company on these new pistols, and if they didn't get the government contract they were going to be in a world of hurt. Of course, DWM had their hands full filling the contracts they already had.

The Army offered contracts for 200 pistols. Colt said okay and then delivered them early, at the contract price of $25 each.

Savage grumbled. They were tooling up for their .32 and .380 pistols (which would make them a lot of money in the times ahead). Their rifles were selling well. The Army wanted only 200 pistols? Well, all right, they could do that, but only at $65 each. The Army agreed, Savage was late on delivery, and worse yet, the 200 they sent didn't all arrive. The shipment was five pistols short. While Savage was wrangling with the railroad about that, the Army inspected the pistols and declared them unsuitable. Not what was ordered. They sent them back, and to add insult to injury, another 70+ pistols disappeared en route. The Army, tired of this nonsense, told Savage 1) to deliver 200 pistols without delay, and 2) that losses in shipment were not their problem. So, in the end, Savage had to make nearly 300 .45 pistols.

DWM declined to produce more pistols. Partly, they felt they had been used, held up as a sacrificial lamb and whipping boy for the two American entrants. That, and the American-supplied ammunition wasn't up to snuff, and the German-made ammo had not been refined enough to be reliable. DWM had lots of other clients, clients who were not persnickety enough to demand a .45 handgun. So after much correspondence between DWM and the US Army, DWM walked off, to make trainloads of 9mm Lugers for their other clients.

The Colt field trials pistols were shipped in March of 1908 and issued to the troops that year. The Savage pistols came later.

The thumb safety was another layer of safety, one that allowed the prospective new pistol to be carried with a chambered round, without requiring the hammer to be lowered for safe carry.

In the time between the 1907 trials and the 1910 trials, Browning and Colt had been busy. Browning completely over-hauled the design. He ditched the dual-link system in favor of a single link and a closed-front slide. No more embarrassing slide launchings. He swapped out flat springs for coil springs wherever he could. He added a thumb safety. The Army had insisted on a safety of some kind, and the quick response had been the grip safety. The thumb safety was another layer of safety, one that allowed the prospective new pistol to be carried with a chambered round, without requiring the hammer to be lowered for safe carry.

In 1910, the Army had the two come back for more endurance testing. The lack of work Savage had done, or not done, was embarrassing. While the new Colt design showed great improvement, it still had shortcomings. The Savage hadn't changed at all. It broke parts, it had malfunctions, it didn't stand up well. It was obvious that Savage had dropped the ball. However, there was still a chance. You see, the Colt wasn't flawless, either. In addition to breaking parts, the Colt experienced some pretty severe frame cracking. In order to make the pistol a bit lighter, Colt machined the openings under the grip plates pretty large. That meant relatively small cross sections in some areas. The 1910 Colt had the frame crack on half a dozen critical areas in firing the scheduled test ammo. One area it cracked in, that is not critical, is still seen today: the thin web of rail above the slide stop tab clearance hole often cracks on high-volume pistols. It doesn't hurt anything. In fact, when Colt came out with the 10mm 75 years later, they simply machined that section away, rather than have owners complain about the crack after a couple of hundred rounds.

The Springfield Arsenal Museum has a Savage on display.

Pistol, .45, Model of 1911, serial number 1. One of the last batch of test pistols, subjected to onerous trials, and surviving to win.

Since the Colt still had problems, the Army ordered another test. This one would be it. If Savage could get their act together, they had a chance. If not, too bad. We all know the results: the Colt fired 6,000 rounds without a malfunction or parts breakage.

Despite having fulfilled contracts with Great Britain, France and Russia for small arms, the American Army had not been granted the budgetary authority to expand.

The rest is history.

Messy history, true, but history. America joined the war effort woefully under-equipped. Despite having fulfilled contracts with Great Britain, France and Russia for small arms, the American Army had not been granted the budgetary authority to expand. Despite the Philippine Insurrection and the 1916 Punitive Expedition against Pancho Villa in northern Mexico, the US Army had not been in active combat on a large scale. They had no real experience above company-sized formations. And they did not have enough small arms to go around. In fact, the Army had shrunk some since the turn of the century, being just under 80,000 men.

While the Army had shrunk, the Navy had expanded. At the beginning of The Great War, the American Navy was among the largest and newest afloat. While we did not have the total size of the fleets of Great Britain, Germany, or Russia, a larger percentage of our largest ships were brand-new. The Great White Fleet, four squadrons of American naval vessels which circumnavigated the world from 1907-09, were not even the newest part. By 1917, nearly half of the US fleet had been built after 1910.

However, the Army did not benefit from the same largesse. Curiously, however, the just under 80,000 men in the Army had an inventory of just under 70,000 1911 pistols.

Remember, as we step into the history of WWI, that those involved fully expected by 1916 for it to last until the Fall of 1919, perhaps even into the Spring of 1920. They planned for men, materiel and supplies to be built during that entire time. While the US Army of Spring 1917 was under 80,000, those in charge fully expected that for the Fall offensive of 1919 they would be commanding and equipping an army of just under a million men. Keep that in mind as you learn about production wrangles, contract volumes and disagreements between companies.