Chapter 3

Business Continuity Planning

THE CISSP EXAM TOPICS COVERED IN THIS CHAPTER INCLUDE:

- ✓ Security and Risk Management (e.g. Security, Risk, Compliance, Law, Regulations, Business Continuity)

- G. Understand business continuity requirements

- G.1 Develop and document project scope and plan

- G.2 Conduct business impact analysis

- G. Understand business continuity requirements

- ✓ Security Operations (e.g. Foundational Concepts, Investigations, Incident Management, Disaster Recovery)

- N. Participate in business continuity planning and exercises

Despite our best wishes, disasters of one form or another eventually strike every organization. Whether it’s a natural disaster such as a hurricane or earthquake or a man-made calamity such as a building fire or burst water pipes, every organization will encounter events that threaten their operations or even their very existence.

Resilient organizations have plans and procedures in place to help mitigate the effects a disaster has on their continuing operations and to speed the return to normal operations. Recognizing the importance of planning for business continuity and disaster recovery, the International Information Systems Security Certification Consortium (ISC)2 included these two processes in the Common Body of Knowledge for the CISSP program. Knowledge of these fundamental topics will help you prepare for the exam and help you prepare your organization for the unexpected.

In this chapter, we’ll explore the concepts behind business continuity planning. Chapter 18, “Disaster Recovery Planning,” will continue our discussion and delve into the specifics of what happens if business continuity controls fail and the organization needs to get its operations back up and running again after a disaster strikes.

Planning for Business Continuity

Business continuity planning (BCP) involves assessing the risks to organizational processes and creating policies, plans, and procedures to minimize the impact those risks might have on the organization if they were to occur. BCP is used to maintain the continuous operation of a business in the event of an emergency situation. The goal of BCP planners is to implement a combination of policies, procedures, and processes such that a potentially disruptive event has as little impact on the business as possible.

BCP focuses on maintaining business operations with reduced or restricted infrastructure capabilities or resources. As long as the continuity of the organization’s ability to perform its mission-critical work tasks is maintained, BCP can be used to manage and restore the environment. If the continuity is broken, then business processes have stopped and the organization is in disaster mode; thus, disaster recovery planning (DRP) takes over.

The overall goal of BCP is to provide a quick, calm, and efficient response in the event of an emergency and to enhance a company’s ability to recover from a disruptive event promptly. The BCP process, as defined by (ISC)2, has four main steps:

- Project scope and planning

- Business impact assessment

- Continuity planning

- Approval and implementation

The next four sections of this chapter cover each of these phases in detail. The last portion of this chapter will introduce some of the critical elements you should consider when compiling documentation of your organization’s business continuity plan.

Project Scope and Planning

As with any formalized business process, the development of a strong business continuity plan requires the use of a proven methodology. This requires the following:

- Structured analysis of the business’s organization from a crisis planning point of view

- The creation of a BCP team with the approval of senior management

- An assessment of the resources available to participate in business continuity activities

- An analysis of the legal and regulatory landscape that governs an organization’s response to a catastrophic event

The exact process you use will depend on the size and nature of your organization and its business. There isn’t a “one-size-fits-all” guide to business continuity project planning. You should consult with project planning professionals within your organization and determine the approach that will work best within your organizational culture.

Business Organization Analysis

One of the first responsibilities of the individuals responsible for business continuity planning is to perform an analysis of the business organization to identify all departments and individuals who have a stake in the BCP process. Here are some areas to consider:

- Operational departments that are responsible for the core services the business provides to its clients

- Critical support services, such as the information technology (IT) department, plant maintenance department, and other groups responsible for the upkeep of systems that support the operational departments

- Senior executives and other key individuals essential for the ongoing viability of the organization

This identification process is critical for two reasons. First, it provides the groundwork necessary to help identify potential members of the BCP team (see the next section). Second, it provides the foundation for the remainder of the BCP process.

Normally, the business organization analysis is performed by the individuals spearheading the BCP effort. This is acceptable, given that they normally use the output of the analysis to assist with the selection of the remaining BCP team members. However, a thorough review of this analysis should be one of the first tasks assigned to the full BCP team when it is convened. This step is critical because the individuals performing the original analysis may have overlooked critical business functions known to BCP team members that represent other parts of the organization. If the team were to continue without revising the organizational analysis, the entire BCP process may be negatively affected, resulting in the development of a plan that does not fully address the emergency-response needs of the organization as a whole.

BCP Team Selection

In many organizations, the IT and/or security departments are given sole responsibility for BCP and no arrangements are made for input from other operational and support departments. In fact, those departments may not even know of the plan’s existence until disaster strikes or is imminent. This is a critical flaw! The isolated development of a business continuity plan can spell disaster in two ways. First, the plan itself may not take into account knowledge possessed only by the individuals responsible for the day-to-day operation of the business. Second, it keeps operational elements “in the dark” about plan specifics until implementation becomes necessary. This reduces the possibility that operational elements will agree with the provisions of the plan and work effectively to implement it. It also denies organizations the benefits achieved by a structured training and testing program for the plan.

To prevent these situations from adversely impacting the BCP process, the individuals responsible for the effort should take special care when selecting the BCP team. The team should include, at a minimum, the following individuals:

- Representatives from each of the organization’s departments responsible for the core services performed by the business

- Representatives from the key support departments identified by the organizational analysis

- IT representatives with technical expertise in areas covered by the BCP

- Security representatives with knowledge of the BCP process

- Legal representatives familiar with corporate legal, regulatory, and contractual responsibilities

- Representatives from senior management

Each one of the individuals mentioned in the preceding list brings a unique perspective to the BCP process and will have individual biases. For example, the representatives from each of the operational departments will often consider their department the most critical to the organization’s continued viability. Although these biases may at first seem divisive, the leader of the BCP effort should embrace them and harness them in a productive manner. If used effectively, the biases will help achieve a healthy balance in the final plan as each representative advocates the needs of their department. On the other hand, if proper leadership isn’t provided, these biases may devolve into destructive turf battles that derail the BCP effort and harm the organization as a whole.

Resource Requirements

After the team validates the business organization analysis, it should turn to an assessment of the resources required by the BCP effort. This involves the resources required by three distinct BCP phases:

BCP Development The BCP team will require some resources to perform the four elements of the BCP process (project scope and planning, business impact assessment, continuity planning, and approval and implementation). It’s more than likely that the major resource consumed by this BCP phase will be effort expended by members of the BCP team and the support staff they call on to assist in the development of the plan.

BCP Testing, Training, and Maintenance The testing, training, and maintenance phases of BCP will require some hardware and software commitments, but once again, the major commitment in this phase will be effort on the part of the employees involved in those activities.

BCP Implementation When a disaster strikes and the BCP team deems it necessary to conduct a full-scale implementation of the business continuity plan, this implementation will require significant resources. This includes a large amount of effort (BCP will likely become the focus of a large part, if not all, of the organization) and the utilization of hard resources. For this reason, it’s important that the team uses its BCP implementation powers judiciously yet decisively.

An effective business continuity plan requires the expenditure of a large amount of resources, ranging all the way from the purchase and deployment of redundant computing facilities to the pencils and paper used by team members scratching out the first drafts of the plan. However, as you saw earlier, personnel are one of the most significant resources consumed by the BCP process. Many security professionals overlook the importance of accounting for labor, but you can rest assured that senior management will not. Business leaders are keenly aware of the effect that time-consuming side activities have on the operational productivity of their organizations and the real cost of personnel in terms of salary, benefits, and lost opportunities. These concerns become especially paramount when you are requesting the time of senior executives.

You should expect that leaders responsible for resource utilization management will put your BCP proposal under a microscope, and you should be prepared to defend the necessity of your plan with coherent, logical arguments that address the business case for BCP.

Legal and Regulatory Requirements

Many industries may find themselves bound by federal, state, and local laws or regulations that require them to implement various degrees of BCP. We’ve already discussed one example in this chapter—the officers and directors of publicly traded firms have a fiduciary responsibility to exercise due diligence in the execution of their business continuity duties. In other circumstances, the requirements (and consequences of failure) might be more severe. Emergency services, such as police, fire, and emergency medical operations, have a responsibility to the community to continue operations in the event of a disaster. Indeed, their services become even more critical in an emergency when public safety is threatened. Failure on their part to implement a solid BCP could result in the loss of life and/or property and the decreased confidence of the population in their government.

In many countries, financial institutions, such as banks, brokerages, and the firms that process their data, are subject to strict government and international banking and securities regulations designed to facilitate their continued operation to ensure the viability of the national economy. When pharmaceutical manufacturers must produce products in less-than-optimal circumstances following a disaster, they are required to certify the purity of their products to government regulators. There are countless other examples of industries that are required to continue operating in the event of an emergency by various laws and regulations.

Even if you’re not bound by any of these considerations, you might have contractual obligations to your clients that require you to implement sound BCP practices. If your contracts include some type of service-level agreement (SLA), you might find yourself in breach of those contracts if a disaster interrupts your ability to service your clients. Many clients may feel sorry for you and want to continue using your products/services, but their own business requirements might force them to sever the relationship and find new suppliers.

On the flip side of the coin, developing a strong, documented business continuity plan can help your organization win new clients and additional business from existing clients. If you can show your customers the sound procedures you have in place to continue serving them in the event of a disaster, they’ll place greater confidence in your firm and might be more likely to choose you as their preferred vendor. Not a bad position to be in!

All of these concerns point to one conclusion—it’s essential to include your organization’s legal counsel in the BCP process. They are intimately familiar with the legal, regulatory, and contractual obligations that apply to your organization and can help your team implement a plan that meets those requirements while ensuring the continued viability of the organization to the benefit of all—employees, shareholders, suppliers, and customers alike.

Business Impact Assessment

Once your BCP team completes the four stages of preparing to create a business continuity plan, it’s time to dive into the heart of the work—the business impact assessment (BIA). The BIA identifies the resources that are critical to an organization’s ongoing viability and the threats posed to those resources. It also assesses the likelihood that each threat will actually occur and the impact those occurrences will have on the business. The results of the BIA provide you with quantitative measures that can help you prioritize the commitment of business continuity resources to the various local, regional, and global risk exposures facing your organization.

It’s important to realize that there are two different types of analyses that business planners use when facing a decision:

Quantitative Decision Making Quantitative decision making involves the use of numbers and formulas to reach a decision. This type of data often expresses options in terms of the dollar value to the business.

Qualitative Decision Making Qualitative decision making takes non-numerical factors, such as emotions, investor/customer confidence, workforce stability, and other concerns, into account. This type of data often results in categories of prioritization (such as high, medium, and low).

The BIA process described in this chapter approaches the problem from both quantitative and qualitative points of view. However, it’s tempting for a BCP team to “go with the numbers” and perform a quantitative assessment while neglecting the somewhat more difficult qualitative assessment. It’s important that the BCP team performs a qualitative analysis of the factors affecting your BCP process. For example, if your business is highly dependent on a few very important clients, your management team is probably willing to suffer significant short-term financial loss in order to retain those clients in the long term. The BCP team must sit down and discuss (preferably with the involvement of senior management) qualitative concerns to develop a comprehensive approach that satisfies all stakeholders.

Identify Priorities

The first BIA task facing the BCP team is identifying business priorities. Depending on your line of business, there will be certain activities that are most essential to your day-to-day operations when disaster strikes. The priority identification task, or criticality prioritization, involves creating a comprehensive list of business processes and ranking them in order of importance. Although this task may seem somewhat daunting, it’s not as hard as it seems.

A great way to divide the workload of this process among the team members is to assign each participant responsibility for drawing up a prioritized list that covers the business functions for which their department is responsible. When the entire BCP team convenes, team members can use those prioritized lists to create a master prioritized list for the entire organization.

This process helps identify business priorities from a qualitative point of view. Recall that we’re describing an attempt to simultaneously develop both qualitative and quantitative BIAs. To begin the quantitative assessment, the BCP team should sit down and draw up a list of organization assets and then assign an asset value (AV) in monetary terms to each asset. These numbers will be used in the remaining BIA steps to develop a financially based BIA.

The second quantitative measure that the team must develop is the maximum tolerable downtime (MTD), sometimes also known as maximum tolerable outage (MTO). The MTD is the maximum length of time a business function can be inoperable without causing irreparable harm to the business. The MTD provides valuable information when you’re performing both BCP and DRP planning.

This leads to another metric, the recovery time objective (RTO), for each business function. This is the amount of time in which you think you can feasibly recover the function in the event of a disruption. Once you have defined your recovery objectives, you can design and plan the procedures necessary to accomplish the recovery tasks.

The goal of the BCP process is to ensure that your RTOs are less than your MTDs, resulting in a situation in which a function should never be unavailable beyond the maximum tolerable downtime.

Risk Identification

The next phase of the BIA is the identification of risks posed to your organization. Some elements of this organization-specific list may come to mind immediately. The identification of other, more obscure risks might take a little creativity on the part of the BCP team.

Risks come in two forms: natural risks and man-made risks. The following list includes some events that pose natural threats:

- Violent storms/hurricanes/tornadoes/blizzards

- Earthquakes

- Mudslides/avalanches

- Volcanic eruptions

Man-made threats include the following events:

- Terrorist acts/wars/civil unrest

- Theft/vandalism

- Fires/explosions

- Prolonged power outages

- Building collapses

- Transportation failures

Remember, these are by no means all-inclusive lists. They merely identify some common risks that many organizations face. You may want to use them as a starting point, but a full listing of risks facing your organization will require input from all members of the BCP team.

The risk identification portion of the process is purely qualitative in nature. At this point in the process, the BCP team should not be concerned about the likelihood that each type of risk will actually materialize or the amount of damage such an occurrence would inflict upon the continued operation of the business. The results of this analysis will drive both the qualitative and quantitative portions of the remaining BIA tasks.

Likelihood Assessment

The preceding step consisted of the BCP team’s drawing up a comprehensive list of the events that can be a threat to an organization. You probably recognized that some events are much more likely to happen than others. For example, a business in Southern California is much more likely to face the risk of an earthquake than to face the risk posed by a volcanic eruption. A business based in Hawaii might have the exact opposite likelihood that each risk would occur.

To account for these differences, the next phase of the business impact assessment identifies the likelihood that each risk will occur. To keep calculations consistent, this assessment is usually expressed in terms of an annualized rate of occurrence (ARO) that reflects the number of times a business expects to experience a given disaster each year.

The BCP team should sit down and determine an ARO for each risk identified in the previous section. These numbers should be based on corporate history, professional experience of team members, and advice from experts, such as meteorologists, seismologists, fire prevention professionals, and other consultants, as needed.

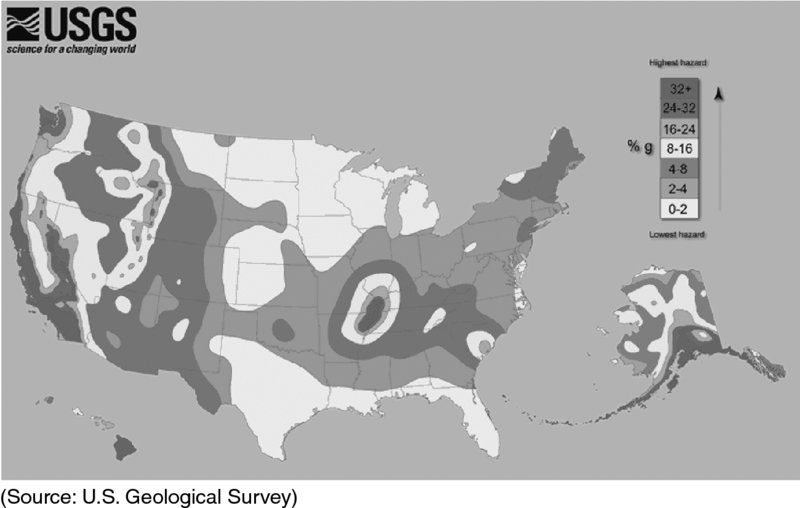

In many cases, you may be able to find likelihood assessments for some risks prepared by experts at no cost to you. For example, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) developed the earthquake hazard map shown in Figure 3.1. This map illustrates the ARO for earthquakes in various regions of the United States. Similarly, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) coordinates the development of detailed flood maps of local communities throughout the United States. These resources are available online and offer a wealth of information to organizations performing a business impact assessment.

Figure 3.1 Earthquake hazard map of the United States

Impact Assessment

As you may have surmised based on its name, the impact assessment is one of the most critical portions of the business impact assessment. In this phase, you analyze the data gathered during risk identification and likelihood assessment and attempt to determine what impact each one of the identified risks would have on the business if it were to occur.

From a quantitative point of view, we will cover three specific metrics: the exposure factor, the single loss expectancy, and the annualized loss expectancy. Each one of these values is computed for each specific risk/asset combination evaluated during the previous phases.

The exposure factor (EF) is the amount of damage that the risk poses to the asset, expressed as a percentage of the asset’s value. For example, if the BCP team consults with fire experts and determines that a building fire would cause 70 percent of the building to be destroyed, the exposure factor of the building to fire is 70 percent.

The single loss expectancy (SLE) is the monetary loss that is expected each time the risk materializes. You can compute the SLE using the following formula:

Continuing with the preceding example, if the building is worth $500,000, the single loss expectancy would be 70 percent of $500,000, or $350,000. You can interpret this figure to mean that a single fire in the building would be expected to cause $350,000 worth of damage.

The annualized loss expectancy (ALE) is the monetary loss that the business expects to occur as a result of the risk harming the asset over the course of a year. You already have all the data necessary to perform this calculation. The SLE is the amount of damage you expect each time a disaster strikes, and the ARO (from the likelihood analysis) is the number of times you expect a disaster to occur each year. You compute the ALE by simply multiplying those two numbers:

Returning once again to our building example, if fire experts predict that a fire will occur in the building once every 30 years, the ARO is ~1/30, or 0.03. The ALE is then 3 percent of the $350,000 SLE, or $11,667. You can interpret this figure to mean that the business should expect to lose $11,667 each year due to a fire in the building.

Obviously, a fire will not occur each year—this figure represents the average cost over the 30 years between fires. It’s not especially useful for budgeting considerations but proves invaluable when attempting to prioritize the assignment of BCP resources to a given risk. These concepts were also covered in Chapter 2, “Personnel Security and Risk Management Concepts.”

From a qualitative point of view, you must consider the nonmonetary impact that interruptions might have on your business. For example, you might want to consider the following:

- Loss of goodwill among your client base

- Loss of employees to other jobs after prolonged downtime

- Social/ethical responsibilities to the community

- Negative publicity

It’s difficult to put dollar values on items like these in order to include them in the quantitative portion of the impact assessment, but they are equally important. After all, if you decimate your client base, you won’t have a business to return to when you’re ready to resume operations!

Resource Prioritization

The final step of the BIA is to prioritize the allocation of business continuity resources to the various risks that you identified and assessed in the preceding tasks of the BIA.

From a quantitative point of view, this process is relatively straightforward. You simply create a list of all the risks you analyzed during the BIA process and sort them in descending order according to the ALE computed during the impact assessment phase. This provides you with a prioritized list of the risks that you should address. Select as many items as you’re willing and able to address simultaneously from the top of the list and work your way down. Eventually, you’ll reach a point at which you’ve exhausted either the list of risks (unlikely!) or all your available resources (much more likely!).

Recall from the previous section that we also stressed the importance of addressing qualitatively important concerns. In previous sections about the BIA, we treated quantitative and qualitative analysis as mainly separate functions with some overlap in the analysis. Now it’s time to merge the two prioritized lists, which is more of an art than a science. You must sit down with the BCP team and representatives from the senior management team and combine the two lists into a single prioritized list.

Qualitative concerns may justify elevating or lowering the priority of risks that already exist on the ALE-sorted quantitative list. For example, if you run a fire suppression company, your number-one priority might be the prevention of a fire in your principal place of business despite the fact that an earthquake might cause more physical damage. The potential loss of reputation within the business community resulting from the destruction of a fire suppression company by fire might be too difficult to overcome and result in the eventual collapse of the business, justifying the increased priority.

Continuity Planning

The first two phases of the BCP process (project scope and planning and the business impact assessment) focus on determining how the BCP process will work and prioritizing the business assets that must be protected against interruption. The next phase of BCP development, continuity planning, focuses on developing and implementing a continuity strategy to minimize the impact realized risks might have on protected assets.

In this section, you’ll learn about the subtasks involved in continuity planning:

- Strategy development

- Provisions and processes

- Plan approval

- Plan implementation

- Training and education

Strategy Development

The strategy development phase bridges the gap between the business impact assessment and the continuity planning phases of BCP development. The BCP team must now take the prioritized list of concerns raised by the quantitative and qualitative resource prioritization exercises and determine which risks will be addressed by the business continuity plan. Fully addressing all the contingencies would require the implementation of provisions and processes that maintain a zero-downtime posture in the face of every possible risk. For obvious reasons, implementing a policy this comprehensive is simply impossible.

The BCP team should look back to the MTD estimates created during the early stages of the BIA and determine which risks are deemed acceptable and which must be mitigated by BCP continuity provisions. Some of these decisions are obvious—the risk of a blizzard striking an operations facility in Egypt is negligible and would be deemed an acceptable risk. The risk of a monsoon in New Delhi is serious enough that it must be mitigated by BCP provisions.

Once the BCP team determines which risks require mitigation and the level of resources that will be committed to each mitigation task, they are ready to move on to the provisions and processes phase of continuity planning.

Provisions and Processes

The provisions and processes phase of continuity planning is the meat of the entire business continuity plan. In this task, the BCP team designs the specific procedures and mechanisms that will mitigate the risks deemed unacceptable during the strategy development stage. Three categories of assets must be protected through BCP provisions and processes: people, buildings/facilities, and infrastructure. In the next three sections, we’ll explore some of the techniques you can use to safeguard these categories.

People

First and foremost, you must ensure that the people within your organization are safe before, during, and after an emergency. Once you’ve achieved that goal, you must make provisions to allow your employees to conduct both their BCP and operational tasks in as normal a manner as possible given the circumstances.

People should be provided with all the resources they need to complete their assigned tasks. At the same time, if circumstances dictate that people be present in the workplace for extended periods of time, arrangements must be made for shelter and food. Any continuity plan that requires these provisions should include detailed instructions for the BCP team in the event of a disaster. The organization should maintain stockpiles of provisions sufficient to feed the operational and support teams for an extended period of time in an accessible location. Plans should specify the periodic rotation of those stockpiles to prevent spoilage.

Buildings and Facilities

Many businesses require specialized facilities in order to carry out their critical operations. These might include standard office facilities, manufacturing plants, operations centers, warehouses, distribution/logistics centers, and repair/maintenance depots, among others. When you perform your BIA, you will identify those facilities that play a critical role in your organization’s continued viability. Your continuity plan should address two areas for each critical facility:

Hardening Provisions Your BCP should outline mechanisms and procedures that can be put in place to protect your existing facilities against the risks defined in the strategy development phase. This might include steps as simple as patching a leaky roof or as complex as installing reinforced hurricane shutters and fireproof walls.

Alternate Sites In the event that it’s not feasible to harden a facility against a risk, your BCP should identify alternate sites where business activities can resume immediately (or at least in a period of time that’s shorter than the maximum tolerable downtime for all affected critical business functions). Chapter 18, “Disaster Recovery Planning,” describes a few of the facility types that might be useful in this stage.

Infrastructure

Every business depends on some sort of infrastructure for its critical processes. For many businesses, a critical part of this infrastructure is an IT backbone of communications and computer systems that process orders, manage the supply chain, handle customer interaction, and perform other business functions. This backbone consists of a number of servers, workstations, and critical communications links between sites. The BCP must address how these systems will be protected against risks identified during the strategy development phase. As with buildings and facilities, there are two main methods of providing this protection:

Physically Hardening Systems You can protect systems against the risks by introducing protective measures such as computer-safe fire suppression systems and uninterruptible power supplies.

Alternative Systems You can also protect business functions by introducing redundancy (either redundant components or completely redundant systems/communications links that rely on different facilities).

These same principles apply to whatever infrastructure components serve your critical business processes—transportation systems, electrical power grids, banking and financial systems, water supplies, and so on.

Plan Approval and Implementation

Once the BCP team completes the design phase of the BCP document, it’s time to gain top-level management endorsement of the plan. If you were fortunate enough to have senior management involvement throughout the development phases of the plan, this should be a relatively straightforward process. On the other hand, if this is your first time approaching management with the BCP document, you should be prepared to provide a lengthy explanation of the plan’s purpose and specific provisions.

Plan Approval

If possible, you should attempt to have the plan endorsed by the top executive in your business—the chief executive officer, chairman, president, or similar business leader. This move demonstrates the importance of the plan to the entire organization and showcases the business leader’s commitment to business continuity. The signature of such an individual on the plan also gives it much greater weight and credibility in the eyes of other senior managers, who might otherwise brush it off as a necessary but trivial IT initiative.

Plan Implementation

Once you’ve received approval from senior management, it’s time to dive in and start implementing your plan. The BCP team should get together and develop an implementation schedule that utilizes the resources dedicated to the program to achieve the stated process and provision goals in as prompt a manner as possible given the scope of the modifications and the organizational climate.

After all the resources are fully deployed, the BCP team should supervise the conduct of an appropriate BCP maintenance program to ensure that the plan remains responsive to evolving business needs.

Training and Education

Training and education are essential elements of the BCP implementation. All personnel who will be involved in the plan (either directly or indirectly) should receive some sort of training on the overall plan and their individual responsibilities.

Everyone in the organization should receive at least a plan overview briefing to provide them with the confidence that business leaders have considered the possible risks posed to continued operation of the business and have put a plan in place to mitigate the impact on the organization should business be disrupted.

People with direct BCP responsibilities should be trained and evaluated on their specific BCP tasks to ensure that they are able to complete them efficiently when disaster strikes. Furthermore, at least one backup person should be trained for every BCP task to ensure redundancy in the event personnel are injured or cannot reach the workplace during an emergency.

BCP Documentation

Documentation is a critical step in the business continuity planning process. Committing your BCP methodology to paper provides several important benefits:

- It ensures that BCP personnel have a written continuity document to reference in the event of an emergency, even if senior BCP team members are not present to guide the effort.

- It provides a historical record of the BCP process that will be useful to future personnel seeking to both understand the reasoning behind various procedures and implement necessary changes in the plan.

- It forces the team members to commit their thoughts to paper—a process that often facilitates the identification of flaws in the plan. Having the plan on paper also allows draft documents to be distributed to individuals not on the BCP team for a “sanity check.”

In the following sections, we’ll explore some of the important components of the written business continuity plan.

Continuity Planning Goals

First, the plan should describe the goals of continuity planning as set forth by the BCP team and senior management. These goals should be decided on at or before the first BCP team meeting and will most likely remain unchanged throughout the life of the BCP.

The most common goal of the BCP is quite simple: to ensure the continuous operation of the business in the face of an emergency situation. Other goals may also be inserted in this section of the document to meet organizational needs. For example, you might have goals that your customer call center experience no more than 15 consecutive minutes of downtime or that your backup servers be able to handle 75 percent of your processing load within 1 hour of activation.

Statement of Importance

The statement of importance reflects the criticality of the BCP to the organization’s continued viability. This document commonly takes the form of a letter to the organization’s employees stating the reason that the organization devoted significant resources to the BCP development process and requesting the cooperation of all personnel in the BCP implementation phase.

Here’s where the importance of senior executive buy-in comes into play. If you can put out this letter under the signature of the CEO or an officer at a similar level, the plan will carry tremendous weight as you attempt to implement changes throughout the organization. If you have the signature of a lower-level manager, you may encounter resistance as you attempt to work with portions of the organization outside of that individual’s direct control.

Statement of Priorities

The statement of priorities flows directly from the identify priorities phase of the business impact assessment. It simply involves listing the functions considered critical to continued business operations in a prioritized order. When listing these priorities, you should also include a statement that they were developed as part of the BCP process and reflect the importance of the functions to continued business operations in the event of an emergency and nothing more. Otherwise, the list of priorities could be used for unintended purposes and result in a political turf battle between competing organizations to the detriment of the business continuity plan.

Statement of Organizational Responsibility

The statement of organizational responsibility also comes from a senior-level executive and can be incorporated into the same letter as the statement of importance. It basically echoes the sentiment that “business continuity is everyone’s responsibility!” The statement of organizational responsibility restates the organization’s commitment to business continuity planning and informs employees, vendors, and affiliates that they are individually expected to do everything they can to assist with the BCP process.

Statement of Urgency and Timing

The statement of urgency and timing expresses the criticality of implementing the BCP and outlines the implementation timetable decided on by the BCP team and agreed to by upper management. The wording of this statement will depend on the actual urgency assigned to the BCP process by the organization’s leadership. If the statement itself is included in the same letter as the statement of priorities and statement of organizational responsibility, the timetable should be included as a separate document. Otherwise, the timetable and this statement can be put into the same document.

Risk Assessment

The risk assessment portion of the BCP documentation essentially recaps the decision-making process undertaken during the business impact assessment. It should include a discussion of all the risks considered during the BIA as well as the quantitative and qualitative analyses performed to assess these risks. For the quantitative analysis, the actual AV, EF, ARO, SLE, and ALE figures should be included. For the qualitative analysis, the thought process behind the risk analysis should be provided to the reader. It’s important to note that the risk assessment must be updated on a regular basis because it reflects a point-in-time assessment.

Risk Acceptance/Mitigation

The risk acceptance/mitigation section of the BCP documentation contains the outcome of the strategy development portion of the BCP process. It should cover each risk identified in the risk analysis portion of the document and outline one of two thought processes:

- For risks that were deemed acceptable, it should outline the reasons the risk was considered acceptable as well as potential future events that might warrant reconsideration of this determination.

- For risks that were deemed unacceptable, it should outline the risk management provisions and processes put into place to reduce the risk to the organization’s continued viability.

Vital Records Program

The BCP documentation should also outline a vital records program for the organization. This document states where critical business records will be stored and the procedures for making and storing backup copies of those records.

One of the biggest challenges in implementing a vital records program is often identifying the vital records in the first place! As many organizations transitioned from paper-based to digital workflows, they often lost the rigor that existed around creating and maintaining formal file structures. Vital records may now be distributed among a wide variety of IT systems and cloud services. Some may be stored on central servers accessible to groups whereas others may be located in digital repositories assigned to an individual employee.

If that messy state of affairs sounds like your current reality, you may wish to begin your vital records program by identifying the records that are truly critical to your business. Sit down with functional leaders and ask, “If we needed to rebuild the organization today in a completely new location without access to any of our computers or files, what records would you need?” Asking the question in this way forces the team to visualize the actual process of re-creating operations and, as they walk through the steps in their minds, will produce an inventory of the organization’s vital records. This inventory may evolve over time as people remember other important information sources, so you should consider using multiple conversations to finalize it.

Once you’ve identified the records that your organization considers vital, the next task is a formidable one: find them! You should be able to identify the storage locations for each record identified in your vital records inventory. Once you’ve completed this task, you can then use this vital records inventory to inform the rest of your business continuity planning efforts.

Emergency-Response Guidelines

The emergency-response guidelines outline the organizational and individual responsibilities for immediate response to an emergency situation. This document provides the first employees to detect an emergency with the steps they should take to activate provisions of the BCP that do not automatically activate. These guidelines should include the following:

- Immediate response procedures (security and safety procedures, fire suppression procedures, notification of appropriate emergency-response agencies, etc.)

- A list of the individuals who should be notified of the incident (executives, BCP team members, etc.)

- Secondary response procedures that first responders should take while waiting for the BCP team to assemble

Your guidelines should be easily accessible to everyone in the organization who may be among the first responders to a crisis incident. Any time a disruption strikes, time is of the essence. Slowdowns in activating your business continuity procedures may result in undesirable downtime for your business operations.

Maintenance

The BCP documentation and the plan itself must be living documents. Every organization encounters nearly constant change, and this dynamic nature ensures that the business’s continuity requirements will also evolve. The BCP team should not be disbanded after the plan is developed but should still meet periodically to discuss the plan and review the results of plan tests to ensure that it continues to meet organizational needs.

Obviously, minor changes to the plan do not require conducting the full BCP development process from scratch; they can simply be made at an informal meeting of the BCP team by unanimous consent. However, keep in mind that drastic changes in an organization’s mission or resources may require going back to the BCP drawing board and beginning again.

Any time you make a change to the BCP, you must practice good version control. All older versions of the BCP should be physically destroyed and replaced by the most current version so that no confusion exists as to the correct implementation of the BCP.

It is also a good practice to include BCP components in job descriptions to ensure that the BCP remains fresh and is performed correctly. Including BCP responsibilities in an employee’s job description also makes them fair game for the performance review process.

Testing and Exercises

The BCP documentation should also outline a formalized exercise program to ensure that the plan remains current and that all personnel are adequately trained to perform their duties in the event of a disaster. The testing process is quite similar to that used for the disaster recovery plan, so we’ll reserve the discussion of the specific test types for Chapter 18.

Summary

Every organization dependent on technological resources for its survival should have a comprehensive business continuity plan in place to ensure the sustained viability of the organization when unforeseen emergencies take place. There are a number of important concepts that underlie solid business continuity planning (BCP) practices, including project scope and planning, business impact assessment, continuity planning, and approval and implementation.

Every organization must have plans and procedures in place to help mitigate the effects a disaster has on continuing operations and to speed the return to normal operations. To determine the risks that your business faces and that require mitigation, you must conduct a business impact assessment from both quantitative and qualitative points of view. You must take the appropriate steps in developing a continuity strategy for your organization and know what to do to weather future disasters.

Finally, you must create the documentation required to ensure that your plan is effectively communicated to present and future BCP team participants. Such documentation should include continuity planning guidelines. The business continuity plan must also contain statements of importance, priorities, organizational responsibility, and urgency and timing. In addition, the documentation should include plans for risk assessment, acceptance, and mitigation; a vital records program; emergency-response guidelines; and plans for maintenance and testing.

Chapter 18 will take this planning to the next step—developing and implementing a disaster recovery plan. The disaster recovery plan kicks in where the business continuity plan leaves off. When an emergency occurs that interrupts your business in spite of the BCP measures, the disaster recovery plan guides the recovery efforts necessary to restore your business to normal operations as quickly as possible.

Exam Essentials

Understand the four steps of the business continuity planning process. Business continuity planning (BCP) involves four distinct phases: project scope and planning, business impact assessment, continuity planning, and approval and implementation. Each task contributes to the overall goal of ensuring that business operations continue uninterrupted in the face of an emergency situation.

Describe how to perform the business organization analysis. In the business organization analysis, the individuals responsible for leading the BCP process determine which departments and individuals have a stake in the business continuity plan. This analysis is used as the foundation for BCP team selection and, after validation by the BCP team, is used to guide the next stages of BCP development.

List the necessary members of the business continuity planning team. The BCP team should contain, at a minimum, representatives from each of the operational and support departments; technical experts from the IT department; security personnel with BCP skills; legal representatives familiar with corporate legal, regulatory, and contractual responsibilities; and representatives from senior management. Additional team members depend on the structure and nature of the organization.

Know the legal and regulatory requirements that face business continuity planners. Business leaders must exercise due diligence to ensure that shareholders’ interests are protected in the event disaster strikes. Some industries are also subject to federal, state, and local regulations that mandate specific BCP procedures. Many businesses also have contractual obligations to their clients that must be met, before and after a disaster.

Explain the steps of the business impact assessment process. The five steps of the business impact assessment process are identification of priorities, risk identification, likelihood assessment, impact assessment, and resource prioritization.

Describe the process used to develop a continuity strategy. During the strategy development phase, the BCP team determines which risks will be mitigated. In the provisions and processes phase, mechanisms and procedures that will mitigate the risks are designed. The plan must then be approved by senior management and implemented. Personnel must also receive training on their roles in the BCP process.

Explain the importance of fully documenting an organization’s business continuity plan. Committing the plan to writing provides the organization with a written record of the procedures to follow when disaster strikes. It prevents the “it’s in my head” syndrome and ensures the orderly progress of events in an emergency.

Written Lab

- Why is it important to include legal representatives on your business continuity planning team?

- What is wrong with the “seat-of-the-pants” approach to business continuity planning?

- What is the difference between quantitative and qualitative risk assessment?

- What critical components should be included in your business continuity training plan?

- What are the four main steps of the business continuity planning process?

Review Questions

What is the first step that individuals responsible for the development of a business continuity plan should perform?

- BCP team selection

- Business organization analysis

- Resource requirements analysis

- Legal and regulatory assessment

Once the BCP team is selected, what should be the first item placed on the team’s agenda?

- Business impact assessment

- Business organization analysis

- Resource requirements analysis

- Legal and regulatory assessment

What is the term used to describe the responsibility of a firm’s officers and directors to ensure that adequate measures are in place to minimize the effect of a disaster on the organization’s continued viability?

- Corporate responsibility

- Disaster requirement

- Due diligence

- Going concern responsibility

What will be the major resource consumed by the BCP process during the BCP phase?

- Hardware

- Software

- Processing time

- Personnel

What unit of measurement should be used to assign quantitative values to assets in the priority identification phase of the business impact assessment?

- Monetary

- Utility

- Importance

- Time

Which one of the following BIA terms identifies the amount of money a business expects to lose to a given risk each year?

- ARO

- SLE

- ALE

- EF

What BIA metric can be used to express the longest time a business function can be unavailable without causing irreparable harm to the organization?

- SLE

- EF

- MTD

- ARO

You are concerned about the risk that an avalanche poses to your $3 million shipping facility. Based on expert opinion, you determine that there is a 5 percent chance that an avalanche will occur each year. Experts advise you that an avalanche would completely destroy your building and require you to rebuild on the same land. Ninety percent of the $3 million value of the facility is attributed to the building and 10 percent is attributed to the land itself. What is the single loss expectancy of your shipping facility to avalanches?

- $3,000,000

- $2,700,000

- $270,000

- $135,000

Referring to the scenario in question 8, what is the annualized loss expectancy?

- $3,000,000

- $2,700,000

- $270,000

- $135,000

You are concerned about the risk that a hurricane poses to your corporate headquarters in South Florida. The building itself is valued at $15 million. After consulting with the National Weather Service, you determine that there is a 10 percent likelihood that a hurricane will strike over the course of a year. You hired a team of architects and engineers who determined that the average hurricane would destroy approximately 50 percent of the building. What is the annualized loss expectancy (ALE)?

- $750,000

- $1.5 million

- $7.5 million

- $15 million

Which task of BCP bridges the gap between the business impact assessment and the continuity planning phases?

- Resource prioritization

- Likelihood assessment

- Strategy development

- Provisions and processes

Which resource should you protect first when designing continuity plan provisions and processes?

- Physical plant

- Infrastructure

- Financial

- People

Which one of the following concerns is not suitable for quantitative measurement during the business impact assessment?

- Loss of a plant

- Damage to a vehicle

- Negative publicity

- Power outage

Lighter Than Air Industries expects that it would lose $10 million if a tornado struck its aircraft operations facility. It expects that a tornado might strike the facility once every 100 years. What is the single loss expectancy for this scenario?

- 0.01

- $10,000,000

- $100,000

- 0.10

Referring to the scenario in question 14, what is the annualized loss expectancy?

- 0.01

- $10,000,000

- $100,000

- 0.10

In which business continuity planning task would you actually design procedures and mechanisms to mitigate risks deemed unacceptable by the BCP team?

- Strategy development

- Business impact assessment

- Provisions and processes

- Resource prioritization

What type of mitigation provision is utilized when redundant communications links are installed?

- Hardening systems

- Defining systems

- Reducing systems

- Alternative systems

What type of plan outlines the procedures to follow when a disaster interrupts the normal operations of a business?

- Business continuity plan

- Business impact assessment

- Disaster recovery plan

- Vulnerability assessment

What is the formula used to compute the single loss expectancy for a risk scenario?

- SLE = AV × EF

- SLE = RO × EF

- SLE = AV × ARO

- SLE = EF × ARO

Of the individuals listed, who would provide the best endorsement for a business continuity plan’s statement of importance?

- Vice president of business operations

- Chief information officer

- Chief executive officer

- Business continuity manager