12

Living Longer

Telomeres, tardigrades, insulin, and zombie cells

The longest life ever authenticated was Jeanne Calment of France, who lived to be more than 122 and died in 1997.1 There doesn’t appear to be anything remarkable in her diet, exercise routine, or other lifestyle details, at least nothing that would suggest a life span longer than anyone else’s. Jeanne enjoyed desserts. She smoked two cigarettes a day from the age of 21 to 117. (Why she quit at 117 is not clear. Of course, quitting can be difficult—maybe it just took her that long.)

What was Jeanne’s secret? Maybe it’s as simple as the old Groucho Marx quote: “Anyone can get old. All you have to do is live long enough.” Or maybe not. When scientists talk about aging we’re not talking about chronological age, because there is a wide variety of ways that people age. What we’re really interested in is the accumulated effect of things that happen to our bodies that cause difficulties. Neuroscientists use the word senescence—just a fancy Latin-rooted word that means to grow old or to age. You can’t do anything to turn back your chronological age, but you can decrease the likelihood of senescence by adopting simple practices.

It has been accepted wisdom for decades that the life span of humans is limited to around 115 years, with only a few exceptions popping up every now and then. A number of explanations for this have been offered, without proof, such as a cellular clock that preprograms our death (which begs the question of why we would be preprogrammed to die). One thing remains constant, however: People do die. As does the hope of reversing income inequality and the illusion that humans are rational. Also pets die. And houseplants. Novelist Chuck Palahniuk (Fight Club) writes that “on a long enough time line, the survival rate for everyone will drop to zero.” Or, as economist John Maynard Keynes famously quipped, “In the long run we are all dead.” The ubiquity of death suggests to some that eventual death is foreordained at the cellular, and therefore genetic, level.

But wait. In the wild, a great number of animal deaths are caused by predators. Our ancient human ancestors typically died at the claws of predators or from infections. Among modern humans, 90 percent of deaths overall are from cancer and cardiovascular disease. If you could remove injury and disease from the equation, might we live forever?

Immortal Animals

When I was eight years old my friend Barbara lived around the corner. Normally, as a self-respecting eight-year-old boy, I would not have played with girls, but Barbara had three older brothers, and she had a BB gun. She climbed trees. She loved playing in the mud in the creek behind her house, and we would spend hours there catching salamanders. She had a scout knife and one day she cut a worm in half. “You can’t kill them,” she said authoritatively. “Both halves will grow into a new worm.” I watched in amazement as both halves squirmed and slithered and eventually found their way back into the water. (Fortunately I am not a Freudian, or I would have to confront an early female archetype during my presexual development cutting a worm in half.)

A few years later in science class we were to collect eight different butterfly species and pin them to a corkboard. I couldn’t find it in me to do it and took a failing grade on the assignment. My college professors brooked no such sentimentality and I found myself working in a monkey lab during my sophomore year.

It turns out that Barbara was wrong about that earthworm. If it survived at all, the part that contained the head would have grown a new tail, but the tail would have continued to writhe and wiggle for a while before dying. But some worm species do regenerate entire new selves from just a small piece of tissue.2 Biologist Mansi Srivastava discovered the gene, EGR, that allows for worms and other animals to regenerate damaged limbs and tissues and functions as a switch turning these regeneration processes off and on.3 This same gene is present in other animals and humans. In an experiment Barbara would have loved, Michael Levin and Tal Shomrat of Tufts University cut the head off of a planarian flatworm and found that the tail, in which no brain tissues remained, could regenerate a new brain.4 The amazing thing is that the new tail-generated worm retained the long-term memories of the old worm. How that works we don’t know yet.

Biologists have identified several species that can theoretically live forever, if only they can avoid predators, accidents, and nosy scientists; they just don’t seem to age or to die of old age. One is a species of jellyfish (Turritopsis dohrnii). When it encounters a life-threatening stressor, it can revert to what is essentially a younger stage of its life and start over. Another is hydras, a collection of several species of freshwater organisms that are about a third of an inch long. Instead of their cells gradually deteriorating over time, they are constantly renewing and staying young, due, we think, to the large amounts of a gene they have called FOXO that encodes for the protein FOXO. (But there must be more to the story than that, because artificially overexpressing FOXO in other animals doesn’t seem to increase longevity.)

Lobsters are not immortal, but they don’t die of aging and disease because of their ability to regenerate missing parts (it’s no coincidence that the word gene is part of the word regenerate) and their ability to have continuous cell multiplication—they just keep on growing and growing. We think lobsters do this through action of the enzyme telomerase. You may recall telomeres from the perception chapter (Chapter 3), the protective caps at the end of DNA sequences that become shorter with each replication. Telomerase rebuilds these end caps. And lobsters have lots of it, in every part of their bodies. Telomerase is plentiful in human embryos, but after we’re born our levels drop dramatically, leaving insufficient amounts to perform all of the telomere repair we would need to extend our lives. That’s probably a good thing, because telomerase also repairs cancer cells, preferentially so over normal cells, allowing the cancer cells to replicate indefinitely.5 So if you were thinking that telomerase therapy might protect you from the effects of aging, as it does for lobsters, the telomerase would somehow need to be adapted to distinguish cancer cells from normal cells, and we don’t know how to do that yet.

My favorite example of a long-lived and possibly immortal animal is the tardigrade, a microscopic (about half a millimeter long) eight-legged creature who looks like something from a sci-fi movie, wrapped in a burlap sack. Here’s one magnified about 250 times:

Tardigrades can survive harsher conditions than any other animal we know of, including exposure to pressure extremes, radiation, lack of oxygen, dehydration, starvation, and even extreme temperatures: They can be frozen or heated past the point of boiling water.6 They can even survive in outer space. (NASA has tested this!) When stressed by adverse conditions, tardigrades enter a kind of superhibernation state in which their metabolism is suspended by 99 percent. They can survive thanks to an unusual type of protein (IDP) that replaces the water in their cells, causing them to transition into a glassy (vitrified) state as they dry out.7 Another protein, called Dsup, protects them from the effects of radiation.

Human Life Span

The study of human longevity has been marked by a great deal of controversy, and a bifurcation of efforts—focusing either on statistical studies of thousands of people at a time or on individual cells and cell assemblies. At both ends of inquiry, scientists study the interaction between genes and the environment (and, to some extent, culture). Epidemiologists and other population scientists have looked at entire groups of people (such as Mediterraneans, with their famous “diet”) to identify trends in lifestyle choices and to conduct genetic studies to better understand the genetic component to longevity—no one doubts that there is one, but the question is how much of the variability in aging can be attributed to genetic differences. Cell biologists and geneticists are trying to understand cellular communication, repair processes, gene expression, and other details. The population studies have suffered from a lack of controlled experiments. Nearly all of the data come from naturalistic, opportunistic experiments. The cellular-level studies are conducted mostly in worms, flies, and other nonhuman organisms, and although these are model systems for humans—all cellular organisms kinda sorta work the same way—translating this knowledge to any practical interventions for human longevity is far from straightforward.

As an example of the first kind, the population analysis, a 2016 study published in Nature argued for a limit to human life span. Analyzing global demographic data, molecular geneticist Jan Vijg and his colleagues argued that improvements in survival rates with age tend to level off after age one hundred and that the age at death of the world’s oldest person has not increased since the 1990s. They surmised from this that the maximum life span of humans is fixed and subject to natural constraints.8 I found this argument odd when I read it. Vijg did not base his conclusions on biology or genetics. Rather than demonstrating the kinds of “preprogrammed cell death” that some have speculated about, or demonstrating that regeneration processes simply become exhausted at some point when accumulated damage becomes too great, Vijg’s approach used only population statistics. He looked at ages of death around the world across several decades and found that for many years, life expectancy, as well as the life span of the oldest living humans, steadily increased and then reached a plateau. If there is a plateau, he reasoned, it must be that human life is limited.

Many scientists questioned Vijg’s data collection methods and his argument; neither Vijg nor his coauthors are demographers or statisticians. “They just shoveled the data into their computer like you’d shovel food into a cow,” said Jim Vaupel, director of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research.9 And there’s a big hole: A cornerstone of scientific reasoning is that just because you didn’t find something doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist. If you had looked at men’s times for the one-mile run between 1850 and 1950, you would have concluded that because no one had ever run a mile in less than four minutes, no one ever would. Although the world record running times improved over this period, from 4:28 to 4:01:4, it seemed to many that four minutes represented a physical limit, a plateau. Then came Roger Bannister, and since then, eighteen new records have been set, the most recent in 1999 by Hicham El Guerrouj, at 3:43:13.10 We don’t know if there is a limit to human longevity, but if 115- and 120-year-olds are dying of diseases, perhaps those diseases can eventually be eradicated. If they’re dying of “parts wearing out,” perhaps medications or technology can extend life, as it already does with artificial hearts and pacemakers. The Achilles’ heel as of today is the brain—we don’t know yet how to fix an aging brain. But that could change.

Two McGill biologists, Bryan Hughes and Siegfried Hekimi, challenged the Nature paper, showing that Vijg’s mathematical assumptions were flawed.11 Based on their own analysis of death records, they came to the opposite conclusion, that no evidence exists for a limit on human life span, and if such a limit exists, it has not yet been reached or identified. Hekimi says he doesn’t know what the age limit might be and believes that “maximum and average lifespans … could continue to increase far into the foreseeable future.12 … No limit to human lifespan can yet be detected.” He’s also quick to point out that a longer life span, say, living to 150, doesn’t mean that these older adults will spend their extra years in miserable health. “The people who live a very long time,” he notes, “were always healthy. They didn’t have heart disease or diabetes.” Thus, a longer life span usually means a longer health span. Sociologist Jay Olshansky, at the School of Public Health at the University of Illinois, disagrees.13 “Hekimi needs to spend some time in a nursing home or Alzheimer’s ward,” he says, “to get a dose of reality.” (Academics can be competitive.)

Shortly after all this brouhaha, an Italian statistician at the University of Rome, Elisabetta Barbi, conducted a thorough analysis of thousands of elderly Italians who had lived to 105 or longer.14 Normally, the risk of dying increases with age—an 80-year-old is significantly more likely to die within the next five years than a 40-year-old. But Barbi’s team found that after 105, the risk of dying flattens out to a plateau, so after that age, your risk of dying in the upcoming year holds at fifty-fifty. Hekimi, who was not involved in the study, praised it.15 It suggests that there may not be a limit, especially if we can figure out how to control diseases that typically afflict people between the ages of 80 and 104. Statistically speaking, if you can make it to 104, it’s smooth sailing from there on. As one research group put it, “Current understanding of the biology of aging points firmly away from any idea that the end of life is itself genetically programmed.”16

That little drop in risk of death that is visible at the one-hundred-year mark would seem to indicate that people who get close to the age of one hundred want to stay alive to see their one hundredth birthday. I know I would.

Blue Zones

So-called blue zones made headlines in 2008 when demographers discovered the four places in the world that had the highest number of people over age one hundred: Nicoya, Costa Rica; Sardinia, Italy; Ikaria, Greece; and Okinawa, Japan (some lists add Del Mar, California). Most people living in the blue zones have the following in common:17

- They are physically active, not through weight and endurance training, but through chores, gardening, and walking as an integrated part of their lives—they move a lot.

- Their lives have a sense of purpose by doing things they find meaningful.

- They have lower levels of stress and a slower pace.

- They have strong family and community ties.

- They follow a varied diet with a moderate caloric intake, but mostly based on plant sources and high-quality food.

Now, all this is appealing because it’s consistent with what we know about healthy lifestyles. But the blue zones are not evidence that they work, because there are a number of statistical flaws in this line of work. Few in the scientific community are taking the blue zones seriously—there are fewer than a dozen papers on the blue zones in peer-reviewed journals, and none in top-tier journals.

First, the people living in the blue zones tend to engage in these positive lifestyle factors, but still only a very, very small number of them live beyond one hundred. Doing these things does not guarantee a long life by any means. Moreover, we don’t know if the particular individuals who do live beyond one hundred are among the ones that practice these behaviors, or if they practice them more or less than the average person.

Most important is the well-known statistical principle of variability and sample size. In small samples (that is, small datasets) you’ll more often encounter observations that deviate from the average (the mean) than in large samples. For example, we know that there are roughly an equal number of male and female infants born. If you look at the ratio in a small hospital, say, where there were only six births, you might find four girls and two boys—67 percent girls. In a large hospital with sixty births, you might find thirty-four girls and twenty-six boys—57 percent girls. With increasing sample size you will tend to get closer to the true distribution. And so it is with aging. The number of people over one hundred years is very small compared to the population of the world—there simply aren’t enough of them for the statistics to be reliable. (Another methodological brouhaha.)

Genetics versus Environment

There’s an old saying that if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Geneticists look for genes that recur in familial patterns that appear to confer certain behavioral or physical predispositions. The problem, though, is that not everything that runs in families is genetic. Consider French speaking, which does run in families. Some would say that there is a gene for speaking French. But they’d be wrong. Children of French-speaking parents are more likely to be taught French than children of non-French speakers. And a couple who speak the same language are more likely to raise children together than a couple who don’t.

Graham Ruby, a bioinformatics scientist, took a hard look at the longevity data from 400 million people.18 It turns out that the true heritability—the influence of genes on longevity—is only around 7 percent, much less than had been previously assumed. It’s true that longevity runs in families, but in Ruby’s study, longevity was almost as likely to show up in nonblood relatives, like in-laws, as in blood relatives. That’s because of a concept called assortative mating. When selecting a mate, most of us tend to be most comfortable with someone who is somewhat like us in terms of physical attractiveness, intellect, sociability, and other traits. That means that we’re choosing people who possess some genes similar to ours, even though we are not closely related. What this all means is that culture and environment—the healthy lifestyle changes you make—are more important than genes for predicting how long you’ll live. (An obvious exception is if you have a gene that strongly determines a fatal disease.) What makes it look like longevity runs in families, then, is all the things other than genes that families share—homes, neighborhoods, access to education and health care, culture, and cuisine.19 So it’s true, for example, that a good, protective variant of the APOE gene keeps showing up again and again in centenarians and, yes, in blue zones and quasi-blue zones.20 But it seems to be telling such a minor part of the story that efforts toward living a longer life are probably better spent elsewhere.

Worms, FOXO, and Insulin

But genetics isn’t just about what traits are inheritable. Your genes play a daily role in encoding the protein sequences that instruct your body in everything it does to keep you healthy and alive. Anything that can interfere with gene expression or replication can impact longevity. Earlier, I mentioned the protein FOXO, which seems to contribute to cellular renewal in hydras. When those FOXO proteins are prevented from functioning, the hydras start to age. We’re just beginning to unravel the role of FOXO in humans.21 We all have FOXO genes; in fact, there are several different kinds, but the way they behave may be different across individuals and across the life span. It turns out that people who live to be ninety or one hundred have a certain form of FOXO that others don’t.

Cynthia Kenyon was able to double the life span of the worm C. elegans by manipulating FOXO, which in turn activates a number of cellular repair and fortification mechanisms that normally decline with aging—it’s as though the cells have some kind of clock in them that is winding down and FOXO reverses it.22 Kenyon explained it this way:23

You can think of FOXO as being like a building superintendent … maybe he’s a little bit lazy, but he’s there, he’s taking care of the building. But it’s deteriorating. And then suddenly, he learns that there’s going to be a hurricane. So he doesn’t actually do anything himself. He gets on the telephone—just like FOXO gets on the DNA—and he calls up the roofer, the window person, the painter, the floor person. And they all come and they fortify the house. And then the hurricane comes through, and the house is in much better condition than it would normally have been in. And not only that, it can also just last longer, even if there isn’t a hurricane. So that’s the concept here for how we think this life extension ability exists.

But get this: Under conditions of stress, FOXO sends out a signal that starts activating the mechanisms that improve the ability of the cell to protect and repair itself. Adding 2 percent glucose to the bacterial diet of C. elegans completely reversed this life span extension, highlighting the important role of insulin in longevity. Upon finding this, Kenyon immediately switched to a low-glycemic diet. “I tried caloric restriction,” she explained, “but I didn’t like being hungry all the time; I gave that up after two days!”24 But you have to follow a diet that’s right for you, or it will be hard to stick to. After a couple of years of the low glycemic diet, Kenyon switched to intermittent fasting, which she still does today, skipping dinners a few times a week.

Kenyon also found that removing part of the worms’ gonadal systems could extend their lives significantly.25 This parallels a finding that castrated men tend to live an average of fourteen years longer than uncastrated men who are similar on all other factors—and the younger they were when castrated, the longer the life span extension, in some cases up to twenty years.26 Italian castrati were also reputed to live longer. The connection between gonads and aging is not yet understood. It clearly involves something more than testosterone—probably something more fundamental—because the worms don’t have testosterone (although exposing them to it can cause adverse neural changes).27

The biology behind human childbirth may also hold clues to aging. By the time we have children, we are no longer children ourselves, and for many of us, the signs of aging are pretty clear. And yet, we give birth to babies—young, unwrinkled humans that show no signs of aging. How can an aged body produce an unaged one? Kenyon studied this in C. elegans and found that just before an egg is fertilized, there appears to be a massive burst of housecleaning in which the egg is swept clean of age-damaged, deformed proteins.28 Kenyon then showed that the same thing happens in frogs. Whether this happens in humans also is an open question, but if it does, the trigger that causes this housecleaning to take place may help to stanch aging.

The Hayflick Limit and Telomeres

You might be thinking that living longer only means that you’re more likely to get Alzheimer’s disease or cancer and have a longer but less pleasant existence. Scientists used to think that too. But we now know that many gene mutations and other interventions that increase longevity also postpone age-related diseases.29

In 1961, anatomist Leonard Hayflick at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia was having trouble getting his experiments to work. For decades, it was accepted wisdom that human cells would continue to duplicate indefinitely. But Hayflick could not get his to. He considered a number of possibilities—that the temperature or humidity in the lab was wrong, that the samples were contaminated, or maybe there was a problem in the way he had prepared the cells. In looking more carefully at his experimental logs, he discovered that it was only the oldest cells that had stopped dividing, while the younger ones continued to divide.

To rule out the possibility of contamination, he put old cells and younger ones in the same glass bottle—it was only the old ones that stopped dividing. He subsequently documented that the limit to human cell division was between forty and sixty cell divisions, or replications (the Hayflick limit is usually cited as fifty).30 Hayflick didn’t know what caused the limit but speculated that cells had some sort of a replicometer, a kind of counter that kept track of how many replications had occurred and then stopped further replications beyond a predefined limit. One of the startling discoveries was that Hayflick could freeze the samples for up to five years, and, when thawed, they’d begin replicating as before and still stop at the forty-to-sixty limit.

Hayflick (now ninety) recalls,31

I proposed that normal human cells have an internal counting mechanism and that they are mortal. This discovery allowed me to show, for the first time, that unlike normal cells, cancer cells are immortal.

I concluded also that these results were telling me something about human aging. This is the first time that evidence was found suggesting that aging might be caused by events occurring inside of cells. Until my discovery scientists thought that aging was caused by events outside of cells (extracellular events) like radiation, cosmic rays, stress, etc.

What I clearly had shown was that the cessation of cell division is a function of the number of times the cell divides or more exactly, that the DNA in the cell copies itself. DNA copies itself only a finite number of times in normal cells and cancer cells must have a method to circumvent this mechanism.

Researchers later found that the Hayflick limit is caused by the shortening of telomeres, the disposable protective cap at the end of each chromosome. Telomeres have been likened to the plastic tips at the ends of shoelaces (aglets) that keep them from unraveling, but it’s a bit more complicated than that. Imagine that your job is to record a music performance. You need to record from the first note, but you don’t necessarily know when that note will be. What you need is a buffer—a count-off (1-2-3-4) or some other signal that tells you things are about to start. This is the role played by the telomeres—they let the transcription factor that copies DNA know that it is time to start transcribing.32 But in this case, it’s as though you hear the count-off (1-2-3-4) and the band starts playing at 4. Your recording has missed one note. Later, a friend wants to record your recording off the radio, but he’s not very alert, and he misses the first note you recorded, meaning his recording is missing two notes altogether. That’s what happens with telomeres—the transcription factor misses a few sequences each time there is a replication, making the telomere a little shorter each time. For the first fifty replications or so it doesn’t matter because telomeres contain filler DNA sequences that don’t carry important information. But after fifty divisions or so, the telomeres have been completely used up, and they can no longer protect the genes. If copying were to start at that point (which it doesn’t), a few strands of important genetic material would fail to be transcribed and all heck could break loose. Thus, when the telomeres get too short, cell division—and thus cellular repair and renewal—stops.

When DNA cells stop dividing, you don’t die immediately—the human body has around 10 trillion cells, each carrying DNA—although it’s well-established that people with short telomeres die younger than people with long telomeres.33 One leading hypothesis is that when telomeres shorten, and cells stop replicating, they enter a state of senescence and begin to gum up the works. But it is still not certain that the telomere shortening is the cause as opposed to simply a marker of trouble.

Telomere length is mediated by a number of factors. Remember Conscientiousness—the propensity to be planful, reliable, and industrious and to adhere to social norms and tolerate delayed gratification? It turns out that childhood Conscientiousness predicts telomere length forty years later, as shown by Sarah Hampson and her colleagues.34 Exercise is associated with increased telomere length and remediating the negative effects of stress.35 A diet of whole foods is associated with increased telomere length, whereas processed foods, especially hot dogs, smoked meats, and sweetened beverages, are associated with decreases in telomere length.36

Social and cultural factors are also important: Neighborhoods with low social cohesion, where people don’t know one another or trust one another, are bad for telomeres, and this is true at all income levels.37 It doesn’t matter to the telomeres whether you’re living in a sketchy part of a major city or you’re in a mansion on a suburban hill—if you do not have friendly relationships with your neighbors, if you don’t actually enjoy talking to them, chances are your telomeres are getting shorter by the day. Human evolution has made us a social species, and friendly human contact mitigates stress—even at the genetic level.

Not all kinds of stress shorten telomeres. Short-term, manageable stressors are actually good for you because they keep you challenged and give you a repertoire of coping skills, strengthening cells through a process called hormesis—this describes anything that in a low dose is helpful but in a high dose is toxic.38 Other examples of hormesis are ultraviolet light (you need some to stimulate the pineal gland and synthesize vitamin D, but too much causes skin cancers and cataracts) and vitamin A (you need a small amount for normal development and eye function, but too much leads to anorexia, headaches, drowsiness, and altered mental states). The kind of stress that shortens telomeres is long-term, chronic stress.39 In particular, long-term caregiving for a family member, job burnout, and serious traumas such as rape, abuse, domestic violence, and bullying are damaging to telomeres. And in general, it takes a long period of stress before your telomeres are damaged—a monthlong crisis at work probably isn’t enough. But when stress is an enduring, defining feature of your life, that’s when your telomeres will get shorter.

As we’ve seen as a theme throughout The Changing Mind, an important moderating factor in the relationship between stress and telomere length is your response to stress. If you’ve developed good methods of coping and you can stay calm, and find reasons to be happy, your telomeres may not take a hit at all. Some people approach difficult events with a “can-do” attitude, a “bring it on” mentality, seeing these events as a challenge and an opportunity to learn; other people cave in to despair. The physiological response to a sudden stressor is that your adrenal gland releases cortisol. In short bursts that is a good thing, a hormetic response that increases your energy. Athletes who have this kind of healthful challenge response during competitions win more often; Olympic athletes and successful people in many domains tend to see life’s problems as challenges to be overcome.40

Mindfulness meditation (the kind favored by the Dalai Lama) increases the activity of telomerase and lengthens telomeres.41 Whether this will eventually lead to increased or decreased cancer risk is not yet known. And, as with the distinction between dietary supplements and food sources of helpful molecules, such as antioxidants, it may turn out that injecting yourself with telomerase has a completely different physiological effect than organically increasing telomerase through healthful activities, such as meditation and exercise.

Chronic pain is a stressor, and stress decreases telomere length. Jeffrey Mogil has just collected new data indicating that the relationship between pain and telomeres might be bidirectional—that telomere dysfunction can cause pain. “We think the reason that telomere dysfunction turns into pain is because after four months—but not before—we start to see cellular senescence in the spinal cord correlating robustly with the amount of pain the mice were in.”42

I’ve heard a lot of patients say that they “can live with” the pain they are in, and I wonder if this is some effort to display toughness and hardiness. If they knew that living in pain could shorten their lives, would they still eschew the physical therapy and medications that might relieve their pain?

Telomerase—a Goldilocks Zone?

Surprisingly, it turns out that excessively long telomeres are also bad for you. In one large study of more than twenty-six thousand people, overall cancer risk increased by 37 percent with doubled telomere length.43 And some cancers were more impacted than others. For people with the longest telomeres, lung cancer risk increased by 90 percent, breast cancer by 48 percent, prostate cancer by 32 percent, and colorectal cancer by 35 percent. The most troubling effect was a more than doubling of the risk for pancreatic cancer. But just to show how complicated the relationship is between telomere length and cancer, those who had the shortest telomeres also had increased risk for certain cancers: 63 percent greater for stomach cancer and 41 percent greater for liver cancer. In a study of 9,127 patients and thirty-one cancer types, telomeres were found to be shorter in tumors and longer in sarcomas and gliomas.44 (Sarcomas are cancers of connective tissues such as bones, tendons, cartilage, muscle, and fat; gliomas are tumors that start in glial cells of the brain or spine.) The relationship between telomere length and telomerase activity in this study remains unclear.

In their book The Telomere Effect, psychiatrist Elissa Epel and molecular biologist Elizabeth Blackburn describe the situation this way (Blackburn won the Nobel Prize for discovering telomerase):45

We need our good Dr. Jekyll telomerase to stay healthy, but if you get too much of it in the wrong cells at the wrong time, telomerase takes on its Mr. Hyde persona to fuel the kind of uncontrolled cell growth that is a hallmark of cancer. Cancer is, basically, cells that won’t stop dividing; it’s often defined as “cell renewal run amok.”

You don’t want to bomb your cells with artificial telomerase that may goad them into taking the road toward becoming cancerous. Unless the telomerase supplement field comes up with more thorough demonstrations of safety in large—and long-term—clinical trials, in our view it’s sensible to skip any pills, cream, or injection that claims it will increase your telomerase.

Siegfried Hekimi concurs, and adds that we would do well to avoid “anything else that is claimed to increase your longevity as clearly no experiment could yet have shown that it does.”46 The research is just too recent for us to have seen long-term effects of any of the potions, tinctures, oils, essences, and supplements that are being marketed to gullible consumers.

Elizabeth Parrish, the CEO of a biotechnology company called BioViva, must not have read Epel and Blackburn’s book or talked to Hekimi.47 Using herself as an experimental subject, she found a doctor in Colombia who was willing to inject telomerase into her intravenously (this is illegal in the United States). So far, four years later, she reports that her telomere length has increased. But telomere length measurements are notoriously imprecise—the change that she reports is well within the margin of error of measurement. The telomerase injections could well fuel cancer and actually shorten her life span and we wouldn’t know it yet because she’s still young at forty-eight. It’s been speculated that telomere shortening evolved as an anticancer adaptation.48 Scientists have labeled Parrish’s self-experimentation pseudoscience and unethical. A pathology professor who was on the board of Parrish’s company resigned when he heard what she had done. The MIT Technology Review called it “a new low in medical quackery.”49

Maybe Parrish should have read the paper coauthored by Leonard Hayflick, Jay Olshansky, and Bruce Carnes in which they stated, unequivocally:50

Disturbingly large numbers of entrepreneurs are luring gullible and frequently desperate customers of all ages to “longevity” clinics, claiming a scientific basis for the antiaging products they recommend and, often, sell. At the same time, the Internet has enabled those who seek lucre from supposed antiaging products to reach new consumers with ease.

Alarmed by these trends, scientists who study aging, including the three of us, have issued a position statement containing this warning: No currently marketed intervention—none—has yet been proved to slow, stop or reverse human aging, and some can be downright dangerous.

People are living longer and longer on average, and this is owing to a number of positive environmental factors such as medical advances, access to clean water, and so on—not to longevity products. Olshansky doubles down on this view in a 2017 paper in which he notes that the best we can hope for now is essentially to increase health span, but that extending life span artificially is still out of reach.51

That doesn’t stop a lot of people from trying, nor does it look like it will slow the multibillion-dollar antiaging industry. I remember reading about the death of Robert Atkins, the physician who popularized the low-carb, high-fat, and high-protein diet bearing his name. He did not live particularly long, dying at age seventy-two after slipping on some ice in New York City and hitting his head. A running, dark joke in my lab was that while the Atkins diet did great things for your heart, it caused people to slip on ice. In fact, at least in Atkins’ own case, it wasn’t so great for his heart, either, as medical records released posthumously revealed that he had hypertension, a heart attack, and congestive heart failure—all the reasons we were told not to eat diets high in animal fat.52 (If you’ve got to choose, it looks like you’re better off getting your calories from fat than from sugar.) Roy Walford, who pioneered and practiced caloric restriction himself, died of ALS at age seventy-nine—that’s pretty old, but not an advertisement for longevity.

Journalist Pagan Kennedy tracked down a number of people who famously tried to live forever, using various for-profit schemes, diets, concoctions, and routines, to see how long they actually lived and what they died of.53 None of them lived especially long and most died young—not of causes directly related to the self-experimentation they were doing, but who really knows? The irony award goes to Jerome Rodale, the founder of Prevention magazine.54 Taping an episode of The Dick Cavett Show in 1971 at age seventy-two, he boasted, “I’ve decided to live to be a hundred … I never felt better in my life!” He died onstage, right there in the interview chair.

We don’t know how long these people would have lived if they hadn’t practiced their favorite longevity regimens, and we don’t have enough people practicing the same regimens under controlled conditions to really track what’s going on. All we have so far are intuitions about what might work.

The Cellular Garbage Problem

Shortened telomeres cause otherwise healthy cells to go senescent. Senescent cells are a double-edged sword. On the one hand, they can’t divide, meaning they don’t go cancerous; cellular senescence is a way to prevent tumors from forming. On the other hand they produce SASP (senescence-associated secretory phenotype)—toxins and inflammatory mediators that do most of the damage that we associate with aging and mortality. You might be thinking, “Why can’t I just take ibuprofen or naproxen sodium, NSAIDs, to cure this?” The reason is that this kind of inflammation doesn’t respond to them. It’s what some people are calling stealth inflammation. (When you examine the tissue under a microscope, you don’t see the standard markers of inflammation, and yet cytokines and chemokines and toxic inflammatory chemicals are being released anyway.)

Normally, when cells die, they are cleaned out by cellular housekeeping processes. But these cells, like zombies in a horror movie, won’t die. So basically, unless the uncontrolled cellular reproduction of cancer gets us, we die in a pile of senescent cellular garbage of our own making. (Memo to self: Lighten up. Enjoy life.)

Biochemist Jan van Deursen and his colleagues found a chemical marker that distinguishes certain senescent cells from healthy ones and then administered a drug called AP20187 that causes those cells to die. Drugs like this are called senolytics (combining the first part of the word senescence with lytic, which means destroying) and the proposed treatment is called senotherapy. Van Deursen found that clearance of these zombie cells in young mice delayed aging.55 In already aged mice, it slowed the progression of age-related disorders. Removing the senescent cells appears to jump-start some of the tissues’ natural repair mechanisms.56 Subsequent work in mice has shown that removing the zombie cells in this way can repair damage from lung disease and damaged cartilage, and it can extend life span by 25 percent.57 It can also prevent memory loss.58

So far, fourteen different senolytics have been identified and tested, but each one works on a different type of senescent cell.59 “There is no doubt that for different indications, different types of drug will need to be developed,” says molecular biologist Nathaniel David.60 “In a perfect world, you wouldn’t have to. But sadly, biology did not get that memo.” As I write this, David’s company, Unity, is in the middle of a clinical trial to inject senolytics directly into damaged tissue, such as arthritic joints. The drug they’re using acts specifically on the kinds of senescent cells that accumulate in the knee.61

Now, the complicated part of all this is that cellular senescence is a good thing—if a cell becomes damaged it could start to divide uncontrollably and cause cancer. One of the risks of using senolytics is that they could interfere with the processes that normally inhibit cancer growth if they target presenescent cells that could go either way—toward zombies or cancer. There are other problems. In rats, senolytics slow down the wound-healing process. None of the known senolytics are yet safe in humans. As one researcher says, “Everything looks good in mice and when you get to people that is where things go wrong.”62 But if they prove otherwise safe in humans, we still run the risk that senolytics could promote cancer. If only there was a way to somehow check the progression of cancer before it takes over.

Two immunologists, Jim Allison and Tasuku Honjo, received the 2018 Nobel Prize for their work on immunotherapy cures for cancer. (Again, cancer is uncontrolled cell division.) Allison has been working on what he calls immune checkpoint blockades. (I mentioned his work in Chapter 5, on emotion.) The goal was to use your own body’s immune system to attack cancers as they form, something our immune system does all the time without our knowing it. Allison says:

The immune system doesn’t know what kind of cancer you have, it just knows there are cells that shouldn’t be there.63 I thought, we can ignore the specific cancer and just create a blockade to the factors that are inhibiting the body’s natural immune response.

T-Cells circulate throughout your system, looking for foreign objects. In 1982, I worked out the structure of the T-Cell, the TCR receptor. Unfortunately a tumor cell doesn’t turn T-Cells on, it requires a second signal, which comes from antigen presenting cells. Specifically the protein CD28 sends the signals that generate the army of immune responses. Now the molecule CTLA-4 turns it off—it’s an inhibitory system. Without CTLA-4 you die, because the immune system attacks everything, nondiscriminately, willy-nilly, including healthy cells and tissue. Another T-Cell off switch is PD-1.

Cancer cells don’t send out the 2nd signal that the immune system needs, the antigen presenting cells, so they get a head start. There is a window during which you can turn off the inhibitory action of CTLA-4 or PD-1 (putting on the brakes) for a few weeks to kill the cancer. This checkpoint blockade should work with any cancer, theoretically.

The US FDA approved the drugs ipilimumab (for CTLA-4) and nivolumab (for PD-1) based on Allison’s work for the treatment of melanoma; the two drugs are sometimes given together. A course of treatment typically involves four intravenous administrations of the drug on separate occasions separated by about three weeks (some melanomas require additional treatments). These are among the first of many immunotherapies on the market, and as such, they are of limited value due to the potential for serious side effects. For ipilimumab alone, the adverse effects include colitis, hepatitis, or severe inflammation of the pituitary gland in 60 percent of patients; 1 percent of patients develop diabetes. It hasn’t been tested on pregnant women, but scientists speculate that it is probably toxic to the fetus. “Unleashing the immune system can have very bad consequences,” Allison says in a wry understatement, “so it needs to be done carefully.”64

According to one analysis, within the first three years after treatment, 80 percent of patients die.65 But for the 20 percent who get past those first three years, the ten-year survival rate is very close to 100 percent. It’s important to put these numbers in perspective. Survival outcomes for patients with advanced melanoma have, historically, been very poor, with a median overall survival around eight months and a five-year survival rate only around 10 percent. Immunotherapy doubles the five-year survival rate. And these drugs, as well as others like them, have now been approved for use in a range of cancers, including melanoma; renal cell carcinoma; Hodgkin’s lymphoma; bladder, head, and neck cancer; Merkel cell carcinoma; and colorectal, gastric, and hepatocellular cancer. For some forms of prostate cancer, a checkpoint inhibitor, Keytruda, that I mentioned earlier in connection with Jimmy Carter, was just announced in 2019 to have received FDA approval. One patient had his PSA levels reduced from over one hundred to less than one within just a few weeks of therapy, and his cancer was eradicated.

The challenge in the coming decade will be to find ways of mitigating side effects, perhaps by targeting the on-off switch to cancer cells and not allowing the drugs to affect other systems. And interactions with other systems need to be studied more closely. If the microbiome in your gut is underdeveloped, perhaps damaged by antibiotics or chemotherapies that cancer patients often use, these therapies don’t work at all. The more diverse your gut biome, the more effective the immunotherapies are. But we don’t know why that is.

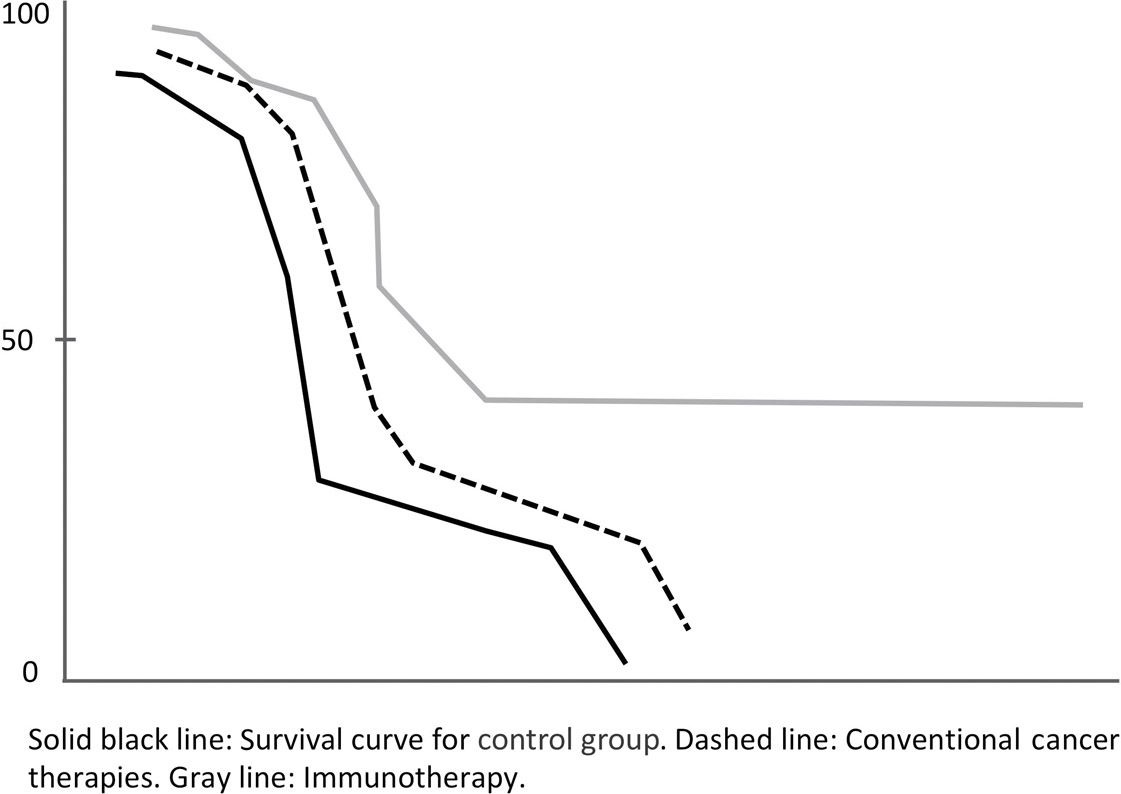

Immunotherapeutic approaches to cancer are getting a lot of laboratory attention. As the techniques become more refined over the coming five to ten years, I predict that they will become increasingly important for longevity, wiping out one of the biggest killers that prevent us from living longer. As the curves above show, conventional therapies have a survival rate of close to zero. Immunotherapy allows for the curve to level off.

All of this is great news, but it’s not the end-all answer to longevity; it’s been calculated that even if cancer were eradicated, it would only extend average life span by seven years—that’s because if you survive cancer, you’ll die of other things, like cardiovascular disease or neurodegeneration. I began this chapter with a hypothetical question: If we could remove all disease, might we live forever? Maybe, but that’s a long way off. Most diseases are caused by the basic biological process of aging. Removing diseases present today would permit a new set of diseases to get you—like a game of Whac-A-Mole. And we probably wouldn’t like those diseases very much either.

Earlier I mentioned prions, misfolded versions of a protein that can spread like an infection by forcing normal copies of that protein into the same misfolded shape. Stan Prusiner won a Nobel Prize for discovering them; it was the first time anyone had shown that a disease could be transmitted not just by an infestation (for example, through bacteria or a virus) but through an infectious protein. Prusiner had long thought that prions were involved in Alzheimer’s disease, but few took him seriously. Recall that Alzheimer’s disease is defined based on the presence of amyloid plaques and tau tangles in the brain, accompanied by cognitive decline.

In 2019, Prusiner and his colleagues at UCSF, Bill DeGrado, Carlo Condello, and others, published an exciting new study based on a postmortem analysis of seventy-five Alzheimer’s patients, in which they found a self-propagating prion form of the proteins amyloid beta and tau.66 Higher levels of these prions in their patients were highly associated with earlier onset forms of Alzheimer’s and a younger age of death. This new finding could lead scientists to explore new therapies that focus on prions directly. “This shows, beyond the shadow of a doubt,” Prusiner told me, “that amyloid beta and tau are both prions, and that Alzheimer’s is a double-prion disorder in which these two rogue proteins destroy the brain.”67 DeGrado adds, “We now know that prion activity correlates with the disease, rather than the amount of plaques and tangles at autopsy.”68 For years, scientists worked on drugs that might clear out the plaques and tangles and made no progress. Now, they can focus on therapies that will target the active prion forms.

Living Forever (Senescence, Revisited)

Aubrey de Grey is the chief science officer of the SENS Research Foundation (Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence). De Grey raised eyebrows when he told the Financial Times that in theory, humans could live to be one thousand.69 De Grey believes he has identified seven types of molecular and cellular damage that he thinks can potentially be repaired: cell loss, cell death resistance, cell overproliferation, intracellular and extracellular “junk,” tissue stiffening, and mitochondrial defects.70 If true, this repair would not just slow down the effects of aging but could actually reverse them. Ethicists and sociologists have already begun speculating what this will mean for things like marriage vows. (Will we stay married to the same person for eight hundred years, or will it be acceptable to change partners every, say, two hundred years?) Or age differences in couples. (Will society consider it scandalous for a five-hundred-year-old man to date a three-hundred-fifty-year-old woman?) If I live to one thousand and have more than ten generations of offspring, I’m going to need to get a bigger table for Thanksgiving dinners.

De Grey’s ideas fall apart when you apply what we actually know about science to them. I’m reminded of the time when the inventor of the PalmPilot, Jeff Hawkins, came to give an address at the Montreal Neurological Institute on how he was going to use technology to improve memory. After taking the podium, he said that he had carefully avoided reading any of the research literature on memory and the brain so as not to be constrained by what other people were doing or had thought about it. This is a typical brash Silicon Valley or start-up approach. Disrupters want to disrupt the status quo. The problem is that every single thing Hawkins suggested stood in direct contradiction to hundreds or thousands of papers about how memory actually works in the brain. To purposefully avoid finding out what are known facts is to waste time pursuing things that either can’t work or are so unlikely to work as to be foolhardy.

So it is with de Grey, according to a great many biologists, immunologists, gerontologists, and neuroscientists. If you are an outsider it all sounds very impressive. To solve the various problems of aging, you employ “senescence marker-tagged toxins … total telomerase deletion plus cell therapy … IL-7 mediated thymopoiesis … allotopic [mitochondrial]-coded proteins … stem cell therapy and growth factors … genetically engineered muscle … periodic exposure to phenacyldimethylthiazolium chloride.”71 Those are impressive-sounding words and it’s easy to be dazzled by them. We may not know what they mean, but it sounds like he knows what he’s doing. A red flag is that among these ideas, he does not propose a testable hypothesis or a specific experiment that will move his research agenda forward.

I get emails like this: “We could teach people to be better musicians just by rewiring their brains surgically. I don’t understand why no one is doing this.”

First of all, we don’t know how to “rewire” the brain—you don’t just connect things up differently, the way you might rewire the electrical outlets in a house. Even if we do figure out a way to move connections between one pair of neurons to another, you’d have to do this to tens or hundreds of thousands of neurons to make a difference. And even if you could do this—automating, for example, with nanorobotic technology we don’t yet possess—how would you know which neurons to rewire? I’m not even mentioning the fact that brain surgery is dangerous and that recovery times are many months. Of the infinity of ideas that are out there, part of the scientist’s job is to select those that are consistent with demonstrable facts and that are actually doable. This is one of the most difficult things to teach graduate students, and many never learn. Those who run successful laboratories choose experiments and research directions that they have theory-based reasons to believe will pan out, and even then, it is typical that 50 to 75 percent of things that we try in our laboratories don’t work for one reason or another.

A 2011 paper pointed out that one of de Grey’s ideas is wholly inconsistent with what we know about mitochondria, the providers of energy in cells (and nothing we’ve learned since then changes that conclusion).72 Another paper in 2014 took issue with his repair-based approach as oblivious to the plethora of unknown variables embedded in the world of cells.73

Other papers have found flaws in de Grey’s ideas. But the real nail in the coffin is something that I’ve hardly ever seen happen in science. A consortium of twenty-eight scientists from different universities and research centers from around the world took it upon themselves to publish a joint, sweeping article debunking his claims.74 They began by quoting H. L. Mencken: “For every complex problem, there is a simple solution, and it is wrong.” Many of the things de Grey has proposed as solutions have already been tested and have never been shown to work in animals, let alone in humans. Other proposed solutions, based on what we know about human physiology, are likely to have harmful side effects that would prevent their use. Those “senescent marker-tagged toxins” de Grey mentions don’t exist. The consortium points out, soberly, what all of us in science know but what journalists and the public often fail to appreciate—that “most therapeutic ideas, even the most plausible, come to nothing—in preclinical studies or clinical research, the proposed interventions are found to be toxic or induce unwelcome side effects … or, most often, simply fail to work.” And the development time for these ideas is decades, not mere years. The twenty-eight scientists conclude quite solemnly—perhaps to counteract the media frenzy that surrounds de Grey’s SENS Research Foundation:

The idea that a research programme organized around the SENS agenda will not only retard ageing, but also reverse it—creating young people from old ones—and do so within our lifetime, is so far from plausible that it commands no respect at all within the informed scientific community.

They continue to say that none of them believe that de Grey’s plans to prevent aging indefinitely, or to “turn old people young again,” have even the remotest chance of success.

We can and must insist that speculation based on evidence be discriminated from speculation based on wish fulfillment alone …. Presenting buzzwords as substitutes for carefully selected and testable hypotheses about ageing … might be clever marketing, but it is a poor substitute for scientific thought.

Aubrey de Grey’s work is a textbook example of pseudoscience, a kind of quackery. Fortunately, there is a lot of evidence-based work that offers hope.

On the Horizon

Drugs like resveratrol and Chloromycetin may mimic the effects of caloric restriction without your actually having to fast.75 Two big studies were conducted with monkeys starting in the eighties, but they had contradictory results. That might be because the control conditions differed; we don’t really know.

A new use for a drug that prevents coronary transplant rejections, rapamycin, may also mimic the effects of caloric restriction. It’s an immunosuppressant, so potentially full of side effects in humans, but in mice it can extend life by 25 percent.76 It’s been tested in other mammals; in dogs it’s too early to tell if it will extend their lives, but it does improve cardiac function, and in human and mouse cell cultures, it appears to have antitumor properties. A study by the drug company Novartis found, counterintuitively (because it’s an immunosuppressant), that weekly doses of rapamycin increased immune function in elderly adults.77

Another experimental treatment is using the diabetes medication metformin—the drug I mentioned in Chapter 9, on diet—to combat aging.78 Researchers aren’t sure why it works, but in mice and humans without diabetes, it appears to mimic caloric restriction and reduce inflammation and oxidative stress, and its use leads to lower risks of getting diabetes, heart disease, cognitive decline, and possibly cancer. The US FDA just approved a study to test it (TAME—Targeting Aging with MEtformin), and we’ll just have to wait a few years to see if it improves health span as hoped.79 One idea about why it might have antiaging effects is that it enhances an enzyme called AMPK (adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase). AMPK helps mimic the beneficial effects of calorie restriction and it can also reduce insulin-like growth factor, or IGF-1, a protein that promotes tumor formation. And if that weren’t enough, it appears to reduce those toxic inflammatory products of senescent cells. Because metformin is one of the oldest and most widely prescribed drugs (it was discovered in the 1950s), many doctors feel safe prescribing it for the off-label use of retarding aging.

Perhaps the most famous new antiaging product on the market is NAD+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide). NAD+ is produced in the brain, and our levels of it decline with age, although fasting increases naturally produced levels. NAD+ supplements may be able to mimic the effects of caloric restriction and have been made famous by articles in Time magazine, Men’s Journal, Good Housekeeping, and others. NAD+ regulates cellular metabolism, cellular signaling, DNA repair, and circadian rhythms and maintains normal mitochondrial function.80 There are several different compounds that raise NAD+ levels in the blood, including nicotinamide riboside (NR), pterostilbene (PT), and nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN).

It’s no coincidence that the first three syllables of NAD+, nicotinamide, sound like nicotine. NAD+ is a form of vitamin B3 and was one of the first vitamins ever discovered. Nicotine, the addictive substance found in tobacco, interferes with absorption of nicotinamide and B3 in the body because of the similarity between the two molecules.81 If you’ve heard that smoking compromises the immune system, this is one of the reasons why.

Geneticist David Sinclair from Harvard is one of the leading players in this field. His work has shown in a number of studies with mice that NAD+ has antiaging properties. After just a week of supplementation, his team could no longer tell the difference between a twenty-four-month-old mouse and a two-month-old mouse—that’s like saying a sixty-year-old human looks like a twenty-year-old.82, 83 (This caused Siegfried Hekimi to quip, “Apparently working too much with NAD makes you unaware that you need glasses.”)

A randomized controlled trial led by MIT biologist Leonard Guarente studied the effects on people who took a combination of two NAD+ precursors, NR and PT.84 Participants were divided into three groups randomly and given either a placebo or a single dose or a double dose of the supplement for eight weeks. The supplement significantly increased levels of NAD+ by 40 percent in the single-dose group and 90 percent in the double-dose group. No serious adverse events were reported. (The study considered a standard dose to be 250 mg of NR and 50 mg of PT per day, and some participants took double that.)

An important complication is that Guarente is the co-founder of a company called Elysium Health that is selling the very compound he tested. This certainly has the appearance of bias. Few scientists will take this finding seriously until it has been replicated by someone who does not have a profit motive. A small study was performed by University of Delaware physiologist Christopher Martens, who used 1,000 mg per day of NR and also found significantly increased levels of NAD+, by 60 percent.85 But this was a very small, exploratory study with only fifteen participants in each experimental group—not nearly enough to make any generalizations.

Another complication is this: All that these two studies showed is that the supplement increases NAD+ levels in the blood—we don’t know whether the risk for cardiovascular events, diabetes, or cancer will be reduced or whether wrinkles will magically disappear and hair become more lustrous. Jeffrey Flier, former dean of Harvard Medical School, has come out against the company for hawking these NAD+ boosters: “Elysium is selling pills [without] evidence that they actually work in humans at all,” a charge that would seem to apply equally to all of the companies selling NAD+ supplements (or antioxidant supplements, for that matter).86 Animal studies on NAD+ have not been easy to replicate, and hundreds of drugs that work in mice never make it to humans. Felipe Sierra of the US National Institute on Aging (NIA), and who of course wants to live a long and healthy life, says:

None of this is ready for prime time.87 The bottom line is I don’t try any of these things. Why don’t I? Because I’m not a mouse.

David Sinclair doesn’t have anything good to say about any of the companies selling boosters. “I have tested the NMN or NR that’s for sale in the market place and I stay clear of those products,” he told me.88 Sinclair has doubts about the purity and contents of the commercially available products, but unlike Felipe Sierra does not harbor doubts about the benefits of boosting NAD+ levels. In fact, the research has persuaded Sinclair to take an NAD+ supplement daily, 1,000 mg of an NMN formulation that is not yet commercially available. He also takes metformin, by the way, 1,000 mg per evening, and 500 mg of resveratrol (pterosilbene) every morning. My advice, based on what I’ve learned from the literature and from Sinclair himself, is to wait for the dust to settle on this whole NAD+ thing. If it becomes approved by the FDA as a drug, rather than a supplement, the purity will be tightly regulated, which it is not now—and it will have been shown to work in humans, not just mice.

Another idea being studied is the possibility of harnessing the power of regeneration that some amphibians possess. The Mexican axolotl, a type of salamander, is about nine inches long and has astonishing abilities to regenerate severed limbs, damaged brain tissue, and even a crushed spinal cord.89 Its genome was just recently sequenced, and you can be sure that researchers on aging will be looking for clues about how genetic therapies might help to regenerate aging human tissue. Interestingly, axolotls do not live particularly long, unlike, say, hydras, but their ability to avoid dying after accidents that would be fatal for most species is a promising direction for future research.

A large number of other drugs are being tested for antiaging properties. One that received a great deal of attention is thioflavin T, a chemical that extended life dramatically in a number of different species of worms, which, perhaps counterintuitively to nonscientists, differ from one another genetically more than mice and humans do. In one species, it doubled life span.90 But of course (to echo Felipe Sierra), humans are not worms.

One of the pernicious difficulties, as you may have gathered from the preceding pages, is that not everything that has a theoretical basis works in practice, and even when it does, not everything that works in a laboratory setting works in the real world. As Richard Klausner, CEO of Lyell Immunopharma, says:91

70–80 percent of findings in science that industry tries to translate to drugs or therapies just don’t work. They worked in one particular cell line in the lab, or one particular set of people. We’ve seen a history of faulty translation. For example, “low fat!” That was a boon for the food industry; less fat, less calories, you can eat more. The current obesity epidemic is a direct result of that faulty translation.

Where Do We Stand?

An octogenarian today can count on living another eight years, four years longer than eighty-year-olds had in 1990. Centenarians live longer than ever before after they have reached one hundred.92 And the number of people over eighty who are making meaningful contributions, to their families, to their communities, and to the world, is increasing as we find health spans increasing dramatically. We are living in a time during which being old means more health and more opportunities than at any point in recorded history. Sixty-year-olds are doing the things that forty-year-olds used to do. It is no longer surprising to hear about people in their eighties who still work. In the United States, eight out of one hundred senators are in their eighties. In the House of Representatives, generally a younger group, nine members are in their eighties. Among Fortune 500 CEOs, five are over seventy-seven. Jane Fonda, eighty-one, is starring in the hit TV show I mentioned earlier, Grace and Frankie, Jiro Ono, aged ninety-four, is considered the world’s greatest sushi chef and still works in his world-class Tokyo restaurants, and Rita Moreno, eighty-eight, just finished a three-year run in another hit TV show (One Day at a Time).

We really don’t know how to extend health span or life span with any certainty. You could avoid smoking, and war, and getting repeatedly hit in the head. You can be conscientious about vaccination, hygiene, exercise, not working too hard, being warm in the winter and cool in the summer, and eating noncontaminated fresh produce all year long …

Or you could be like Jeanne Calment and smoke until you’re 117. Or like Richard Overton, the oldest surviving World War II veteran (at the time of his death), who lived to be 112 and whose secret to a long life was cigars (twelve a day), whiskey, and coffee (with three teaspoons of sugar).93 Fate is capricious.