On Friday evening, January 16, 2014, the tiny town of La Alberca in the mountains above Salamanca is busy with preparations for the big day ahead: Mariluz Lorenzo is in the back of her sweets shop, sculpting tempered chocolate and toasted nuts to look like links of blood sausage; Demetrio González fills glass bottles with licor de cereza, made with cherries soaked in aguardiente for five months until the fruit and the firewater are nearly indistinguishable; the cooks from La Catedral make patatas meneás, boiling and mashing hundreds of pounds of yellow potatoes, mixing them with olive oil and smoked paprika until they turn orange, then topping with crunchy curls of fried pork belly and points of pickled peppers; María Martín lays out her best blouse, her handkerchief, the stockings and jewelry—the same outfit she wears every year to the festival, plus a few extra layers to fight the cold winds she’s seen in the forecast (“I think this will do just fine,” she says to herself in the mirror); the women of Entrevinos, a small wine bar in an alley off the main plaza, polish wine glasses and fry up chunks of farinato redolent of garlic and crushed cumin seeds; Ana María González works her way through a long prep list for the various feasts that will take place tomorrow: seventeen kilograms of heart, thirty of ribs, fifteen of pork belly, and thirty kilos of ground pork to be made into chorizo; Hilaria García works the streets, selling up the last of the thick book of raffle tickets she started with a month ago; don Poldo dusts off his magical castañuelas and cracks his wrists; Mayor Jesús Pascual Bares runs over the notes for his speech, just a little bit different from the speech he gave last year and the year before that; María Jesús walks the rough stone streets, ringing an iron bell and chanting a prayer to keep away the evil spirits believed to lurk beyond the borders of the village; and in a quiet, damp corner of town, in the same pen he’s lived in for the past six months, Antón the pig sleeps soundly, unaware that tomorrow will be his last day on earth.

![]()

On that same Friday morning, Santiago Martín is having a tough time getting out of bed. Normally he wakes at 6:00 a.m., eats a breakfast of toasted bread soaked with olive oil and salt, and drinks coffee with steamed milk, then makes it into the Fermín factory outside of town by 7:00 a.m., just in time for the day’s sacrifice. He knows that there are 140 pigs to slaughter this morning between sunrise and 10:30 a.m., when the workers break to eat their midmorning bocadillos.

But today Santiago is sick, fighting a nagging cold—a by-product, no doubt, of La Alberca’s biting winter weather—and he hits the alarm, goes back to sleep, and dreams of something he won’t remember when he wakes up two hours later.

Meanwhile, at his plant, the pigs to be slaughtered that day arrive from the acorn patches and begin their inexorable march toward the end. Once in the pen, they sense something is wrong—making little squeals, darting this way and that—but two men slowly and calmly usher them to the edge of the pen and through the small doorway that leads onto the killing floor.

From there, the end comes quickly. A conveyor system moves the pigs onto a narrow, padded escalator, where each animal receives an electric shock, and by the time they land on the belt before the matarife, the factory’s designated killer, they are unconscious. Andrés Luis is young by matarife standards, but he’s been on the floor at Fermín for ten years, which means he’s killed tens of thousands of pigs in his short life. He works with a remarkable economy of motion, the look on his face frozen in the same state of muted seriousness. To kill, he makes two cuts, the first a shallow slice with a short, stubby knife to the neck to expose as much of the heart as possible, the second with a long, thin blade plunged directly into the heart, which ends the animal’s life almost instantly. Combined with the electric shock, this is as swift and painless as death can be.

The pig is attached by its back two feet to a metal hanger, a contraption that hoists the carcass into the air and carries it from station to station until the animal has been divided into its primal parts. The processing is quick and exacting: First, the pig is scalded in hot water, then spun in what looks like an industrial dryer to loosen all the hair from its skin. It passes through flames next to burn off any remaining hairs before arriving to the series of butchers who will take the animal apart piece by piece: first the entrails, then the vital organs, then the front and hind legs, ribs, and loin.

In total, a crew of ten can process 140 pigs in just under three hours. The team works calmly, cleanly. There is no way around it: This is a tough business, and the air in the room—warm with the smell of blood and burned hair—will never let them forget where they are. But they take pride in the efficiency and humanity they bring to the messy business of death. In Spain, they don’t say they “kill” animals; they “sacrifice” them.

By 10:30 a.m., after all of the day’s pigs have been sacrificed, the team transitions from the killing floor into the butchering room, where a conveyor belt moves the primal cuts from one employee to the next, each carving out his or her designated piece with a long, narrow blade before returning it to the belt. Organs and specialty cuts like secreto and pluma will be sold fresh in Fermín’s butcher shop in La Alberca, but most of the pig will be seasoned and cured in some way: loins are rubbed in smoked paprika and garlic and cured for three months to make lomo. Front legs are coarsely ground and turned into chorizo, salchichón, and cabeceros. And the hind legs move up to the salt room, where they are buried in coarse salt for two weeks before spending the next three years curing ever so slowly into jamón ibérico de bellota, the most prized charcuterie in the world, and the heart of Fermín’s business.

THEY TAKE PRIDE IN THE EFFICIENCY AND HUMANITY THEY BRING TO THE MESSY BUSINESS OF DEATH.

![]()

Matt Goulding

By the time I finish my tour of the Fermín factory, Santiago has arrived to the office and is busy taking phone calls and meeting with his top lieutenants. His business consists largely of mobilizing a team of farmers, butchers, inspectors, and sales representatives, and he goes about it with the steady, stoic persistence of a marathon runner. He is a large, imposing man with a thick, black beard that carpets the bottom half of his face. His eyes peak out from the thicket of hair and hard features like two lighthouses in a dark sea, conveying information in concentrated flashes. Despite the framed photos of him in crisp suits shaking the hands of politicians and dignitaries around the world, Santiago looks more like a lumberjack than a businessman, the kind of guy you want on your side when shit goes sideways.

January is the busiest time of the year at Fermín. The acorns begin to fall from the trees in October, marking the beginning of the montanera, the period of intense fattening that will ready the pigs for slaughter. Over the past three months, the Fermín pigs have nearly tripled in size, and with the acorn supply dwindling in the dead of winter, their days are numbered. Santiago talks to Victor, the man responsible for raising the company’s pigs on a one-hundred-acre farm nearby. The big news today is that a wild boar broke into one of the pigpens and had its way with some of the animals. “We will have to kill those pigs,” Santiago says grimly.

His sister Paqui occupies a similar office across the hall, where, as part owner of Fermín, she handles the company’s logistics. His brother-in-law, Halem Guerrero, handles the finances. His daughter, Soraya, helps with marketing and public relations. Somewhere in America, his nephew, Raul, is busy introducing jamón to a public slow to warm to its joys.

At 1:00 p.m., Santiago emerges from behind the closed door. “Let’s eat,” he says to nobody in particular.

![]()

There is no animal better suited for consumption than the pig. Easy to raise, easy to feed, easy to kill, and easy to butcher, with a pitch-perfect balance of fat and protein: cure it, smoke it, braise it, sear it—the variety of tastes and textures you can tease from pork is unrivaled in the animal kingdom. Perhaps the great twentieth-century philosopher Homer Simpson said it best: “Oh yeah, right, Lisa, a wonderful, magical animal!” Hot dogs and headcheese, trotters and tenderloins, though nearly half of the world’s population is religiously precluded from partaking in the earthly delights of cured and cooked pork, pig remains the most essential of edible animals, utilitarian and sensual at equal turns. For every hickory-smoked shoulder, there’s an Oscar Mayer wiener, every plump pork chop a crispy piece of bacon—a ying to the yang, fat and succulence, protein and sustenance, a world of food issues expressed through the flesh of its most despised and beloved conspirator. If this year is the year of the pig, may it forever be so.

As some of history’s greatest civilizations—the Romans and Gauls, the Celts and the Chinese—knew, pork reaches its fullest potential only when salt enters the equation. The first records of salted meat stretch back three thousand years to China, where industrious eaters worked out a crude version of what would become Jinhua ham. In 160 BC, the Roman counselor and epicure Cato the Elder wrote extensively about the union of pork and salt, leaving behind a detailed manual for how to cure, smoke, and dry ham. Later, the rest of Europe—the French and Germans, Czechs and Poles—followed with their own adaptations of the basic formula of pork, salt, and cool mountain air. Even the early settlers of the New World got in on the act, feeding their hogs peanuts and air-drying them in the style of their ancestors to create country ham.

Cured meat is the story of humans no longer living hand to mouth. By adding salt to anything, you initiate a potentially long, complex process of enzymatic breakdown with a few huge upsides. First and foremost, you dramatically inhibit microbial growth, extending the life of meat by months or years. But more important for our story is the other principle benefit of curing: the alchemic transformation of salt and time, which work in tandem to extract water and convert proteins into amino acids, giving cured pork its savory, umami richness. It’s not the history or the ingenuity or the long shelf life that chefs and artisans and distinguished palates the world over crave; it’s the intensified flavor.

The Iberians are ancient masters of salt. From Portuguese salt cod to the fish sauce known as garum made during Roman times to the culture of salted and cured tuna parts dating back three millennia to the Phoenicians, they have harnessed NaCl as effectively as any civilization. Though bacalao and fish sauce are invaluable contributions to the canon of world cuisine, pork was their masterpiece.

The pig has long been a barometer for the complex religious and cultural changes Spain has undergone over the centuries. After enjoying a sporadic place at the table during Roman and Gothic times, pork was banned during centuries of Moorish rule, eaten only in the northern pockets of resistance. Indeed, pork and pork fat became the official flavor of the Reconquista, galvanizing the Catholics during their brutal seven-century-long expulsion of the Moors. During the ensuing Inquisition—when those lucky enough to survive could either convert or leave the country—conspicuous consumption of pork became a way for Jews and Muslims to demonstrate allegiance to their new religion. What better way to throw off the scent of a skeptical Catholic inspector than to hang salt pork in your pantry or stir a bit of bacon into your beans—a tactic that, according to some food scholars, explains how so many of Spain’s iconic dishes ended up with bits of pork in them. In the centuries since, pork has come to dominate Spanish cuisine in a way few animals have elsewhere.

Nearly every region of Spain has developed its own tradition surrounding the killing, butchering, and fabrication of the pig—la matanza, they call it, a two-thousand-year-old technique of turning a single animal into a year’s worth of eating. The list of regional specialties to emerge from the matanza culture is staggering. Mallorcans make sobrassada, a soft, spreadable sausage stained red with paprika. In Burgos, morcilla, blood sausage, comes laced with grains of cooked rice. The Asturian town of Tineo specializes in chosco, a blend of head, tongue, paprika, and garlic smoked over oak and chestnut wood.

Regardless of the region, the most noble part of the pig in Spain has always been the leg, a symphony of skin and sinew, protein and intramuscular marbling, held together by two bones that lend an elegant shape and a sturdy structure for hanging and, later, for ceremonious carving. The front leg, leaner, more vital to a pig’s movements and therefore more muscular, is called paletilla; the hind leg, more prized for its bulk and fat content, is, of course, called jamón.

There are many classes of jamón in Spain—everything from jamón dulce (basic boiled ham used on sandwiches) to jamón serrano (salt-cured for twenty-four months). What makes jamón ibérico (what some people call pata negra for the black feet of the pig, or Jabugo after one of the most famous producing towns) so special is a potent blend of nature and nurture: The breed of pig, a descendant of wild boar, is known for its uncanny ability to filter fat through its muscles. Raised on a diet of grass and cereal grains from birth, the most prized ibérico pigs spend the final months of their lives roaming freely in the countryside, fattening up on the fallen acorns that give the meat its intense flavor and sweet deposits of fat. It’s hard to imagine a happier time for an animal that lives to eat, and the results are reflected in its ever-increasing bulk; in the final two months of its life, a pig gains between 50 to 75 percent of its total body weight eating acorns. (Lucky for consumers, all those acorns convert mainly into heart-healthy oleic acid.)

Roaming the dehesa in search of fallen acorns.

Matt Goulding

After the slaughter and the salting, the legs are hung in a series of rooms carefully controlled for temperature and humidity. Three to four years later, you have what any reasonable soul would recognize as the most elegant and delicious piece of protein in the world. At two hundred dollars or more per kilo, it is also one of the most expensive.

Most parts of Spain produce ham of some sort, but over the years, three regions have emerged as the heart of the country’s jamón industry: Andalusia in the south, Extremadura in the far west along the Portuguese border, and Castilla y León to the northwest of Madrid. Each is home to small mountain towns with skilled artisans and the ideal conditions—cool temperatures and constant airflow—for curing ham.

Salamanca, 120 miles west of Madrid, is the heart of Castilla y León. It’s a city of stone buildings and student bodies, home to the second-oldest university in Europe and a spectacular collection of old cathedrals, towers, and palaces. Few leisure activities in Spain can top a stroll through the old part of Salamanca at night, when the crowds shrink and the subtle lighting against the ancient stonework gives the city a magnificent glow.

Carnivores eat like kings in Castilla y León. Restaurant menus are dominated by oven-roasted milk-fed lamb and crispy suckling pig, inch-thick steaks called chuletones cooked bloody, and offal-heavy creations like chanfaina, a slow-cooked stew of aromatics and vital organs. With Guijuelo, one of the capitals of Spain’s artisan pig industry, close by, cured pork greets you at every turn, in logs of cured sausage and empanadas of chorizo and dangling legs of jamón.

Fifty miles to the south, 3,400 feet up in Las Batuecas Natural Park, La Alberca remains one of Spain’s best-preserved medieval villages: streets of stone, homes of hardwood, citizens made of the stern stuff acquired in the quieter corners of civilization. People have lived here since before the Romans came to Spain, an ever-adapting receptacle for the Christian, Jewish, and Islamic cultures that dominate Spanish history. Tucked into the oak and chestnut groves of the Sierra de Francia, La Alberca is shire-like in its beauty and charm and self-reliance, the kind of town you dream of stumbling upon after a few dozen wrong turns.

You won’t find much in La Alberca in terms of commerce—a smattering of restaurants and bars, shops selling local goods, and, of course, a cluster of butchers selling fresh and cured pork from the Fermín factory down the road. This is a town that survives largely on the bounty of the pig—if you don’t work in the factory or in one of the meat shops, your wife or son or brother-in-law surely does.

It’s only fitting, then, that its most famous citizen isn’t the mayor or a local newscaster or even Santiago Martín, but the pig they call Antón. In the summer, at three months old, he is moved from the countryside to the village, where he spends the rest of the year freely wandering the cobblestone streets, fattening off the generosity of the villagers, who feed him grains and table scraps. The pig is named for San Antón, the patron saint of animals, whose legacy La Alberca celebrates in January in a rousing street party filled with music, dancing, and an abundance of fresh and cured pork.

The tradition dates back to the Middle Ages, when, at the end of the festival, Antón went to the poorest family in town, but these days, the village sells raffle tickets to the hundreds that stream in from around the region to drink cherry firewater and eat blood sausage and maybe, just maybe, win three hundred pounds’ worth of the world’s most prized pig.

![]()

Fermín Martín was always out in front of the pack. As a young entrepreneur he wandered the countryside around La Alberca, going from town to town with a herd of goats, selling them for slaughter. In 1956 he and his wife, Victoriana, moved the burgeoning business to a small house he bought just above the central plaza in La Alberca. The house had two floors—the first floor for killing and butchering the animals, the second floor for family living. Victoriana sold the meat while Fermín handled the business of death. When young Santiago came home from school, he would press his ear to the door to listen for the sounds of sacrifice before entering to avoid any unpleasantness.

Business was slow in the tiny village, so before slaughtering an animal, Fermín would knock on doors and ask the villagers—the town doctor, the mayor, people who could afford to buy meat—if anyone was interested in buying a piece. Back then, every family had their own pig, which they would kill in the streets in December or January, but fresh pork wasn’t available the rest of the year, and Fermín saw a chance to change that.

He worked with a partner in those early years, a neighbor and a friend, but soon they both came to accept that the business wasn’t big enough to support two families. So they made a pact: the two men would draw straws, and whoever drew the short straw would pack his bags and move to France. To underscore the seriousness of the wager, both men got passports for themselves and their families beforehand.

With his partner out of the way—true to his word, he moved his family to France that same year and became a mechanic—Fermín began to slowly expand production, moving the business to a larger house and gaining a reputation in the county for the quality of his fresh and cured meat.

During this time, his son, Santiago, and daughter, Paqui, left to study in Salamanca. Santiago, not seeing a future in the pork business for himself, went to medical school. After doing his residence, he spent years as a roaming family doctor, often with a trunk full of hams for delivery across the region. In 1983 his father had a heart attack and the family brooded on the fate of the business. With a new factory recently built and debt mounting, Santiago put down the stethoscope and stepped in to run Embutidos Fermín. “It was either put aside medicine or sell the business, and a bit of my macho pride as the only son wouldn’t let that happen.”

With his full attention turned to Fermín, Santiago began to expand operations, gradually growing the small space just outside of La Alberca into a factory capable of processing enough pig to expand Fermín’s footprint beyond the region. “Instead of curing people, I cure hams.”

Downstairs, below the factory, is a cavernous brick bunker with a fireplace, a bar, and a long wooden table for group meals. It’s dark and dank like the curing rooms upstairs, without flash or pretense; nevertheless, the Martín family has hosted Spanish royalty, famous chefs, the ambassador of China in this subterranean space.

Santiago has invited the whole family to lunch today: his younger sister, Paqui, and her husband, Halem; his older sister, María, and her husband, Pedro, who own and operate the Fermín butcher store in town; and Ana María González, not family by blood, but by bond. Ana came to La Alberca when she was a teenager and was raised by Santiago’s parents as a fourth child. She has extensive experience in nearly every corner of the business—from butchering and quality control to sales and administration. She even helped raise the children of the three siblings.

Ana is the family cook, and today’s spread, unsurprisingly, centers on a potpourri of pig: wedges of hornazo, a local pastry made with lard and stuffed with all manners of cured pork; wood-grilled hunks of prized parts, fresh from the slaughter; and, of course, plates of Fermín embutidos: rosy pink slices of cured loin, burgundy coins of chorizo, and two wooden boards paved with jamón ibérico de bellota.

Santiago picks up a slice of jamón and holds it between us. “This is the only product that Spain can offer to the world that no one else can.”

Spain has long suffered from an inferiority complex in the culinary world, the by-product of having France and Italy as its neighbors. ¡España no se vende bien! It’s a refrain you’ll hear all over the country: Spain doesn’t sell itself well! It’s hard to argue the power of Spain’s pantry: lusty red wines; bright, bracing whites and sparklings; soulful cheese from goat, sheep, and cow; spices and dry goods worthy of the world’s adulation. Spanish olive oils consistently win the big international competitions, beating out the other Mediterranean powerhouses. When it surfaced that Italians were buying up huge quantities of Spanish olive oil, slapping Italian stickers on the bottles, then selling it for three times the price it fetched with a Made in Spain label, a national scandal erupted.

But Santiago is right when he says that jamón ibérico is different. It’s a category killer, a product so vastly superior to other international interpretations that they don’t even merit comparison. Yes, Italy produces fine cured hams, but next to a slice of three-year, acorn-fed, black-footed jamón, prosciutto tastes like lunchmeat. If Spain wants to flex its soft power, it has no better ambassador than the ibérico pig.

In 1995, Santiago decided it was time to take the taste of Spain to the rest of the world. He targeted wealthy Asian countries like Japan and Singapore, but above all, he wanted to crack into the American market. At the time jamón ibérico was still banned by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), but the Americans had released a set of regulations and guidelines that served as a road map for importation. With a newly remodeled factory and a firm control of sanitary issues, Santiago saw it as a sure bet for Fermín.

“I was amazed that none of our competitors were trying to break into the biggest market in the world,” he says. “I thought we’d be selling jamón in the US the next year.”

Not so fast, jefe. The USDA, with its byzantine laws and joyless enforcers, specializes in keeping culinary treasures out of America. Never mind that the product is two thousand years older than the United States itself, and that jamón has little history of health or contamination issues, the USDA put up every roadblock imaginable for importation: grueling plant inspections, endless paperwork, ever-shifting standards and regulations. As the years dragged on, the future of Fermín hung in limbo.

In 2005, after a decade of denials and disappointments, Fermín became the first company to sell jamón ibérico in the United States. They’ve since been joined by competitors like Cinco Jotas and Joselito but maintain a strong foothold in the young market—selling 80 percent of their total production in the States. As someone whose life was improved immeasurably by Fermín’s breakthrough, I tell Santiago he and the family are doing God’s work, but when he speaks about the troubles of selling Spanish ham in America—the draconian rules of the USDA, the enormous effort it takes to educate a public accustomed to paying a quarter of the price for prosciutto—all the wrong facial muscles go to work. “We thought it would be a gold mine,” he says with a deep sigh. “If we don’t accelerate, we’ll never make our investment back.”

Taste a slice of proper jamón and you will understand Santiago’s frustrations. Acorn-fed ham is so rich with fat that it sweats as soon as it’s exposed to air. Rub the fat on your lips like a balm, then place the slice on your tongue like a communion wafer and wait for it to convert you. First you taste the salt, then the pork, then the fermentation, and finally some deep, primal flavor will rise up and scratch at your throat and leave behind a ghost that can haunt your palate for a lifetime.

As Santiago talks, I indulge my habit: not just lacy veils of jamón, but planks of pluma—taken from the neck—so soft and rippled with fat that it could double as foie and chunks of secreto, cut from the skirt of meat below the ribs, with a salty crust from the fire and a marvelous chew. I hold up a slice of lomo and let the light illuminate the rivers of fat that run through it. Lomo might not have the fame of jamón, but Fermín’s take on it is stunning, with an earthiness and perfume that recalls toasted hazelnuts and shaved truffle.

The rest of the family doesn’t eat much. Maybe they’ve grown tired of their treasure, or maybe they’re worried about tomorrow’s pig more than today’s. For the past twenty-eight years, Antón has been donated to La Alberca by Fermín. It’s a magical tradition, this of the free-roaming village-fed beast, but not one without its unexpected twists. Some unsavory souls in a moving van once kidnapped Antón and made for Salamanca; the police tracked them down on a country road and recovered the pig. A few years ago, a group of hikers found Antón on top of the area’s highest peak, miles away from La Alberca; the mayor had to climb up and coerce him back to town. One year, Antón disappeared without a trace. The people of La Alberca accused an old man who had fallen on hard times of killing and eating him. Years later, they found the skeleton of the pig underneath a building where it had been trapped, exonerating the man who had died months before.

“I’ve never had a problem with a pig in my whole life,” says Santiago, with his pet pig Nino.

Matt Goulding

![]()

At 10:00 a.m. on Saturday, January 17, the fiesta explodes. There is no other verb to describe it. By midmorning, the town has swollen to twice its pre-Antón population and an electric current courses over the rough stones that pock La Alberca’s wandering streets. A band sets up in the center of the plaza and a group of middle-aged men and women form adjacent lines and start dancing—partners organized in two lines that spin, dip, and clap in coordinated sequences. Don Poldo, dressed in black from head to toe, leads the charge with his clacking castañuelas, echoing the rhythm of the band by flickering his fingers.

Antón barely seems to notice the people pouring into this cobblestoned world of his, petting his back, posing for pictures—now and always, his main objective is food. When he arrived on the streets of La Alberca on June 13, Antón weighed just 120 pounds. Today, he weighs more than three times that, and shows no sign of slowing down.

One by one, the people who spent days or weeks preparing for the event take their places in pockets around the village: Marialusa sits at her regular table next to the fountain, a shawl on her shoulder and a scarf on her head, slicing up chunks of her famous chocolate morcilla for a crowd clamoring for a taste. Santiago Hernández Vázquez proudly shows off his collection of killing tools from the matanzas of yesteryear, sharpening blades on a wheel of rough stone powered by a creaky wooden pedal. Demetrio and his young son serve up shots of fruit-spiked firewater, using long metal skewers to stab the cherries floating in the bottle and convey them to passersby. The liquor is sweet and bracing, but the fruit itself delivers all the danger. With the exception of the out-of-towners and their modern-day accoutrements—most come in from Salamanca with smartphones unholstered—this could be a scene from a century of your choosing.

This is my third festival, so the scene has a warm, comfortable glow to it now. Wasn’t always so. The first time I came, with José Andrés and a band of American chefs here to take in the pork culture, we all basically lost our minds. We were a roving spectacle for the locals, almost as popular as Antón himself: a group of eight disheveled chefs and an ill-prepared journalist, hangovers stuck to our clothes like wine stains, blinking and drinking our way through cold morning light until José, the year’s guest of honor, took to the balcony to deliver a fiery speech invoking the greatness of Spain and its unrivaled culture of pig.

Suddenly, wineskins and herbal liquors materialized and our hangovers were painted over with fresh coats of intoxication. People pulled us this way and that, to one tavern to try this liquor or to another to dance this number, until finally we were all gathered around one long table in the backroom of a bar with people slapping us on the back and men dancing on the bar and José spooning caviar onto slices of jamón and placing these absurd little packages directly into our mouths, the pork and the fish eggs caught in a beautiful struggle for the upper hand. I announced then—to a stranger at the bar—that I would be back one day to win Antón.

It is with a small but unshakable sense of pride that I walk the streets this morning, shaking hands with people who remember that day and still call me el periodista—the journalist. “You’re loving this, aren’t you?” my wife ribs me as I introduce her to my drinking buddies. I am not one of them, but she is, and maybe that means something. Or maybe not.

At least we look the part. The Fermín family has dressed the two of us in traditional garb—a charcoal button-down shirt with white pin stripes for me, a billowy flowered skirt, pearls, and a headscarf for her. People mistake us for locals and pose for photos. I carry a wineskin slung over my shoulder, which I refill at the bars around the plaza, and all day, strangers come up and they spray tight streams of red wine into the recesses of their mouths.

How the sausage gets made on the streets of La Alberca.

Matt Goulding

A news crew from Salamanca interviews me about the market for Spanish ham in the States. “Americans love pork, so there is hope.” “But people there know what acorn-fed ham is, right?” “The good ones do.”

A multicourse feast unfolds in the four corners of the plaza. An old woman fries dough in olive oil and dusts it with powdered sugar. Cooks from the local restaurants pass out plates of smoky patatas meneás. María and a group of older women initiate what can only be described as a live sausage demonstration, folding the seventy pounds of pork Ana lovingly ground yesterday with garlic and pimenton and hand-cranking it through an ancient sausage stuffer into long coils of sheep intestine. Taut and tied, the chorizo goes straight into a cast-iron cauldron of olive oil bubbling over a wood fire. Crowds descend, waiting for a piece of this or one of the other porcine treats emerging from that magic cauldron: crispy brown ribs, fragrant chunks of morcilla dark with pig’s blood.

The team I saw yesterday working the killing floor at Fermín is all here: the woman with the thick forearms has traded the cleaver for a golden flower of fried dough, the guy who oversees the salting squeezes through the crowd with plates of potatoes for his kids, the matarife canoodles his wife in the corner.

In the center of the plaza with his wife, Rosa, at his side, Santiago surveys the scene, a look of stony seriousness—his default expression—on his face. In a sea of pork-and booze-fueled revelry, he is a port of quiet containment, working out the challenges of tomorrow. Does Raul have the samples he needs for Whole Foods? The factory in Tamames needs reinforcements on Monday. Kill the wild boar. Please don’t let the pig go to this shit-eating writer with the cheesy wineskin.

From time to time, he breaks from his thousand-yard stare to shake the hand of a villager or an employee who comes to pay his respects.

At noon, with the crowd frisky off the firewater, the mayor takes to a large balcony overlooking the plaza and makes his speech. “We are in the most beautiful town of Spain, if not the entire world!” Then, the year’s guest of honor, a novelist who wrote La Alberca into her latest work, steps up to draw a winner from the five thousand raffle tickets (“a new record!”) sold this year. I clutch the ten I’ve bought over the last few days, including three right at the cutoff line, but luck is not on my side: the pig goes to someone from Salamanca.

The feast, though, goes on. By 1:00 p.m., we’ve been swept up into a bar where wine and swine make the rounds. Santiago’s daughter Soraya shares a few stories from festivals past, and the granite facade of her father begins to show signs of cracking. He saves his smiles for when he means them most, which gives moments like these gravity. The whole family is here, including Noelia and Myriam, Santiago’s two other daughters who have come in from Salamanca for the party. I ask Noelia why she is one of the few in the extended family not to work for Fermín. “I’ve watched my dad go to work every day from six a.m. until nine p.m.,” she says. “I didn’t want to follow in those footsteps.”

We cross the plaza to El Balcón, where the band and the dancers have taken over. Don Poldo, the costar of San Antón, dominates the space with his clacking castañuelas, capable of shaking from these little circles of wood a world of ecstasy and agony. At eighty-three he is still able to turn his entire body into an instrument. A chorus of olés ring out from all over the bar. Wineskins are refilled and passed around the circle, my village people costume by now bloodred around the collar.

One of his daughters lets it escape that Santiago keeps a pet pig at his house: Jacob, with tiny legs and a dark belly that scrapes the ground, his own little Antón, only without the expiration date.

“You can’t work in this business unless you care for the animals,” says Santiago. “I’ve never had a single problem with a pig in my life.”

Santiago invites us to his house above the village for one last feast of Fermín’s finest with his family, and they take off in front of us to get the fire going. We stick around for another drink and a few last rounds of don Poldo’s bittersweet vibrations.

When we exit the bar at 3:00 p.m., the plaza is empty. No fried flowers, no hand-cranked chorizo, no camera crews. The morning revelers are on their way back to Salamanca and the locals are sitting down to lunch at private tables across the village. The only noise left in the plaza is the click-clop of Antón’s black cloven hooves as he waddles his way around the fountain, alone once again. Maybe his new owner has yet to claim him, or perhaps somebody from Fermín will round him up later, but he continues to roam La Alberca like a free radical, wet nose to the cold stone, sniffing his way from crumb to crumb, doing what he was born to do.

There will be another pig next year, and he will also be called Antón, and he will sweep these streets for six months, fattening himself on the generosity of townspeople who long ago stopped being surprised to see a beast on their doorstep, and on a cold Saturday in January, after the last of the cherry liquor has been drank, the chocolate morcillas consumed, the plates of patatas meneás scraped clean, the speeches given, the cameras flashed, the music faded, there will be only two things left for Antón: salt and time.

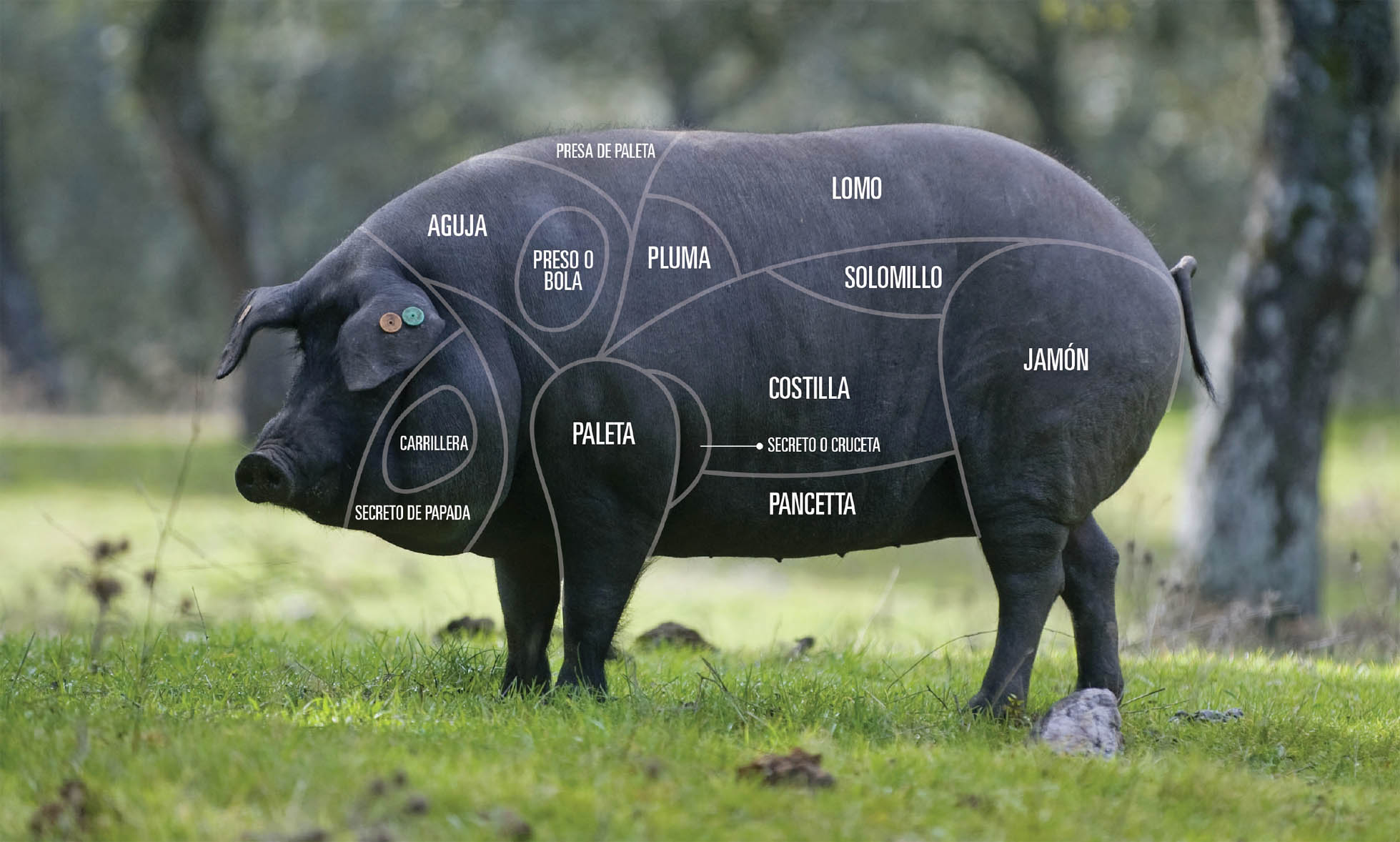

Best Cuts

FROM SNOUT TO TAIL

You can tell how serious a culture is about an animal by how thoroughly they butcher it. When you raise black-footed ibérico pigs on a diet of fallen acorns and open spaces, nothing goes to waste.

Spain is the land of porcine dreams, where regions are defined by the charcuterie (embutidos) they produce. These are six of the provincial stars of the cured pork world.

Matt Goulding

![]() JAMÓN IBÉRICO DE BELLOTA

JAMÓN IBÉRICO DE BELLOTA

The king of cured pork

![]() CHORIZO RIOJANO

CHORIZO RIOJANO

Smoky sausage of La Rioja

![]() LOMO EMBUCHADO

LOMO EMBUCHADO

Garlic, paprika, loin

![]() SOBRASSADA

SOBRASSADA

Mallorca’s spreadable pork

![]() FUET

FUET

Salami a la Catalunya

![]() MORCILLA DE BURGOS

MORCILLA DE BURGOS

Rice, spice, and blood

Life Skills

Douglas Hughmanick

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

![]() ORDER LIKE A LOCAL

ORDER LIKE A LOCAL

Spain possesses one of Europe’s great regional drinking cultures, where the beverage of choice changes from one town to the next. Want to fit into a crowd of Andalusians watching a bullfight in the bar? Order a manzanilla or a fino and brace for the blood.

![]() DRINK IT SMALL AND COLD

DRINK IT SMALL AND COLD

Artisanal beer is on the march in the north, from producers like Edge and Basqueland Brewing Project, but most Spaniards drink light, regional pilsners—Mahou, Estrella Damm, San Miguel—as cold as possible, in small (8- or 12-ounce) servings.

Matt Goulding

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

![]() LET THE VERMOUTH FLOW

LET THE VERMOUTH FLOW

Vermouth culture has made a huge comeback in recent years. Sweet, dark house-made vermú is popular in the late afternoons, and on weekends as a warm-up before a big lunch.

![]() DON’T SIP THE SIDRA

DON’T SIP THE SIDRA

Asturias produces less wine than any other region in Spain, focusing instead on turning its bounty of apples into sparkling hard cider. Sidrerías dominate the social and culinary landscape of the region. There are many rules to cider (discussed in Chapter 6), but most important, don’t sip it; drink it all back in one animated gulp.

Matt Goulding

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

![]() TAKE TO THE STREETS

TAKE TO THE STREETS

Most Spaniards wouldn’t be caught dead drinking on the street, but the youth have mastered the art of the sprawling outdoor boozefest called botellón. Looking to recapture your youth? Grab a bottle and join in.

![]() SKIP THE SANGRIA

SKIP THE SANGRIA

Pass on the goblets of purple potion being proffered along Spain’s most trampled thoroughfares—La Rambla, Plaza del Sol, anywhere in Sevilla. Sangria is largely a tourist trick—a way for unscrupulous restaurants to charge a premium for cheap wine and sugar.

Matt Goulding

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

![]() BASQUE IN THE BUBBLES

BASQUE IN THE BUBBLES

Txakoli is the social lubricant that keeps the bars and restaurants buzzing across the Basque region. A dry, lightly sparkling wine poured from on high to aerate it (a la sidra), txakoli pairs beautifully with the seafood and pintxos that dominate Basque cuisine.

![]() SAVE THE STRONG STUFF

SAVE THE STRONG STUFF

A warm-up beer or a glass of wine is as much as most Spaniards are willing to drink on an empty stomach. Cocktails (especially “gin tonics”) flow freely in the small hours after dinner.

Matt Goulding