The story of modern Basque cuisine doesn’t begin with the towering figures of culinary fame that have become household names across Spain: Arzak, Andoni, Berasategui, Subijana. It doesn’t begin with long, explosive tapas crawls through the Parte Vieja of San Sebastián or Bilbao’s Casco Viejo. It begins in 1946, in the basement kitchen of the Hotel Maria Cristina, where fifteen-year-old Luis Irizar Zamora spent his first days as an apprentice peeling potatoes. It would be three more years before he earned a dime in his role as a young cook, but he was slowly accumulating the skills that would help dramatically transform the shape and trajectory of modern Basque cuisine.

This wasn’t just any hotel kitchen that young Luis apprenticed in. This was sacred ground in San Sebastián, the hotel’s name taken from the city’s most illustrious fan, the young queen regent who in 1893 chose this cool coastal oasis as her respite from royal life in Madrid. Since then, it’s been a summer playground for politicians, celebrities, and royalty looking to escape the heat of inner Iberia. Many of the wealthy—including French aristocrats pouring in from the north—traveled with their own brigade of chefs, who began to slowly impart upon the local cooks a body of knowledge and technique that would have a profound impact on Basque cuisine.

Luis had peeled a few potatoes in his early years. His parents ran a family restaurant in Igueldo, a rural outpost not far from San Sebastián, where as a young boy he pitched in where he could. The family had cows and a garden and served the kind of classic Basque food that helped fuel the region’s industrializing workforce. But his first professional job, one in a busy hotel kitchen responsible for feeding some of Spain’s wealthiest and most powerful people, suggested a great, wide culinary world, and awakened in Luis a desire to explore it all.

The early Franco years was a tough time to be cooking in Spain. Four years of civil war had depleted the national pantry and gutted the agricultural system. Strict rationing made running a high-end restaurant nearly impossible. At his next job, as a kitchen assistant at the polished Monte Igueldo, Luis specialized in culinary contraband, working with French purveyors to sneak caviar, lobsters, foie gras, and other luxury ingredients across the border. “There was no other way to cook seriously during those years.”

Despite the lean times, Luis proved a resourceful young worker, doing whatever he had to do to open the next door and continue sharpening his skill set. From black market border runs, he moved south to Madrid to work at the Hotel Ritz and later cooked classic continental fare at Jockey, the type of top-tier places largely insulated from the whims of the outside world. He butchered game, made salads and terrines, worked on the line, accumulating a bank of knowledge that would take him far in the restaurant world.

Luis was the wandering chef before chefs wandered—kept in motion not by money, but by the promise of the next lesson, the new experience that would shape him into a better cook. Today you can trace the grooves in the earth worn by ambitious young cooks traveling between Noma, El Celler de Can Roca, and the other great restaurants of the world, stacking their résumés with short stints in flashy kitchens. In 1950, in Spain, though, you were lucky enough to have a job, let alone an ambitious life plan.

Recognizing the limit to what he could learn in Spain, Luis traveled north to Paris, the center of the gastronomic world, to cook refined French cuisine at the Hotel California. The chef was a tyrant, more feared than loved by his young cooks, whom he tormented for the tiniest transgressions. Smelling possible peril, Luis studied French and worked twice as hard as his French colleagues. The chef took notice, and rewarded Luis by teaching him the secrets to being one of Paris’s top sauciers. “The time in France was tough, but I considered it my doctorate.”

After France, Luis migrated across the English Channel, following the opportunities as they presented themselves: a stint at a Spanish restaurant with flamenco in London, five years as chef in a high-end Mediterranean restaurant, two years in a classic English pub, where he transposed his scattered biography onto the menu: classic French, Mediterranean, Basque. His next appointment would be his most important to date, as chef at the London Hilton, where he captained a team of cooks responsible for running the hotel’s ecosystem of restaurants and banquet rooms, serving an average of 3,500 meals a day. The five-hundred-room Hilton was one of London’s most important hotels and business centers, where the English elite sought to outdo each other in escalating shows of luxury and ostentation.

In those early years, Luis had the olive-oil good looks of a rising mob boss, his eyes and his tight-lipped smile transmitting a sly disbelief, as if he never thought his crazy plan would actually work out. Throughout his career, he surrounded himself with a trusted crew of captains and consiglieri, guys loyal to him and willing to do whatever it took to execute his vision. A photo from the Hilton in 1965 shows a team of sixty-six chefs in their whites, Luis sitting in the center, arms crossed, grinning.

During the London years, Luis and his wife, Virginia, had four daughters, and after a decade in England, the chef found himself exhausted and homesick. In 1966, an extraordinary opportunity brought him back to his Basque Country: a businessman named Dionisio Barandiarán had purchased and reformed a hotel in the resort town of Zarautz, and he wanted Luis to run the kitchen and the attached cooking school, the first official culinary school in the region.

Spanish cuisine passed through a dark period in the years Luis spent cooking his way around Europe. When people talk about the cuisines of poverty that developed in rural France and Italy, challenging conditions that birthed such rustic masterpieces as pot-au-feu and ribollita, they refer to cultures that transformed scraps of meat and garden vegetables into works of edible art. Spain’s wasn’t a cuisine of poverty; it was one of desperation. One of the most popular recipes of the postwar years was written by Ignasi Domènech, called tortilla de patatas sin patatas ni huevos: potato omelet without potatoes or eggs. Domènech advised his countrymen to use a slurry of flour and water to mimic the egg, and discarded orange peels to approximate the texture of potato.

What began as a profound lack of resources in the famine-riddled postwar years gave way to an overall absence of direction and leadership in the culinary community as Spain recovered in the 1950s. General Franco, who openly espoused a food philosophy of sacrifice and who showed hostility toward anything hinting at decadence (despite his own well-known sweet tooth), did little to inspire his country’s gastronomy. Luis saw in the new position an opportunity to reinvigorate the entire foundation of Basque cuisine. This was a time when required military service and authoritarian rule made it difficult for Spaniards to leave the country. If cooks couldn’t travel through Europe, Luis would bring Europe to them. He taught them the mother sauces he mastered in Paris, the pâtés and charcuterie from a stint in Switzerland, the sense of teamwork and organization accumulated during years of running a sprawling hotel team at the Hilton.

On the other end of those lessons was a student body destined to be some of the most famous chefs in the country. Ramón Roteta, José Ramón Elizondo, Pedro Subijana, Karlos Arguiñano: all formed part of that first class of 1966, later dubbed the Triumphant Generation, a family of chefs that would shape Basque cuisine into a potent blend of European haute and Spanish avant-garde.

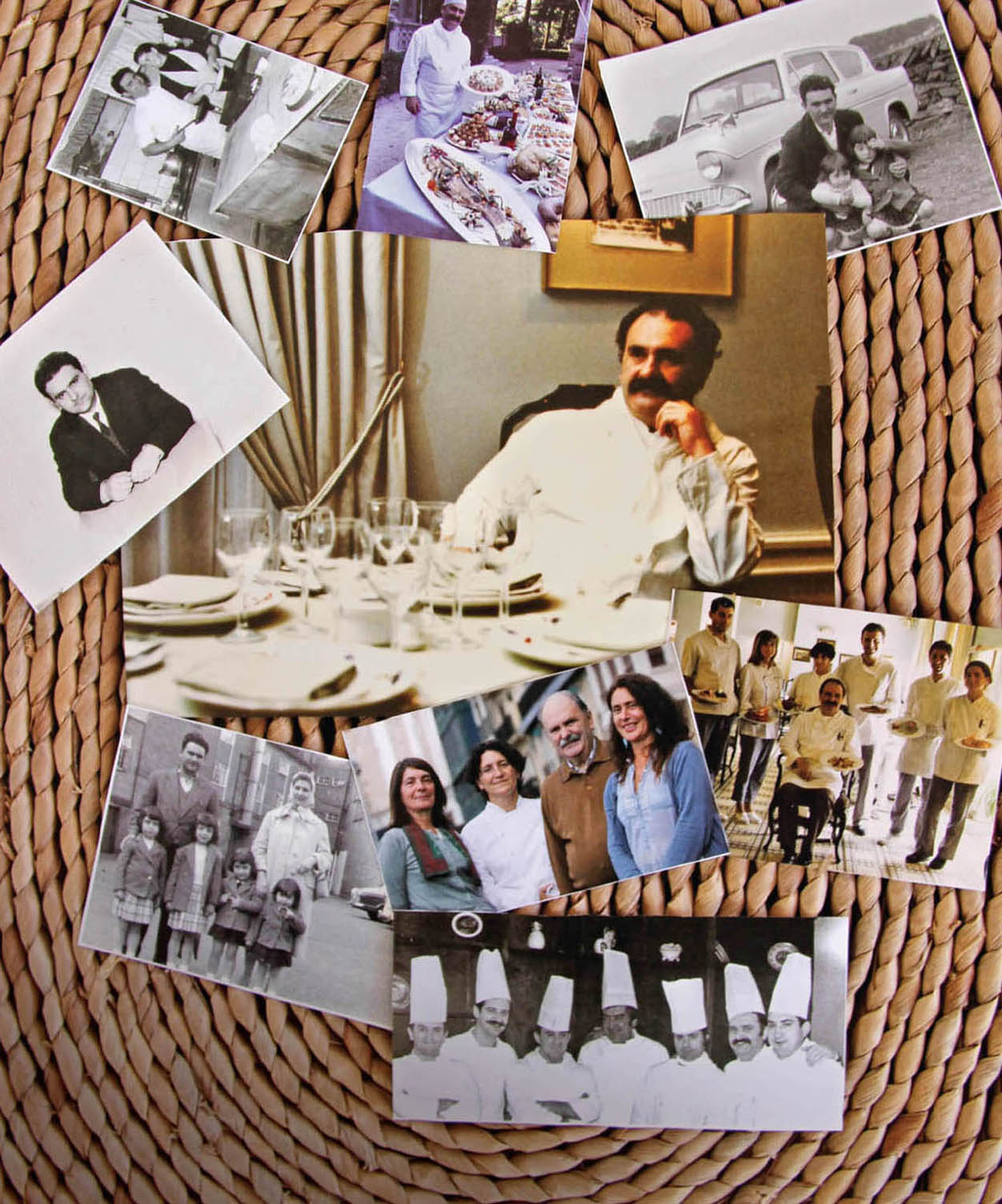

The many faces of Luis Irizar.

Matt Goulding

But before the triumph, a world of challenges awaited Luis and his band of vaunted vascos. Toward the end of the Franco years, a new form of civil war broke out, this one waged between the central government and Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) a vehement group of Basque separatists seeking independence from Spain. Basques have long been known as a proud, independent body. Euskera, the Basque language (an impossible collision of consonants with nothing in common with Spanish), is said to be Europe’s oldest, and many scholars believe that the Basques were the first to settle the Iberian Peninsula. ETA sought to carve out an independent nation on the back of this pride, and turned to increasingly desperate measures of violence to make their point—a terror campaign of kidnappings, bombings, and political executions that gripped the country for more than three decades.

The entire region felt the collateral damage. Tourism disappeared, restaurants suffered, hotels emptied. Luis remembers violent protests that erupted on Christmas of 1970; within days, hundreds of holiday reservations were canceled. Euromar, once a beacon in a culinary world long left to operate in the darkness, shuttered in 1973.

The new generation of Basque chefs had never been better prepared to usher in a new age of gastronomy, but suddenly they didn’t have the clients to cook for. To help fight the growing tide of isolation, and inspired by the young gunslingers of French nouvelle cuisine across the border, a group of fourteen chefs formed the pact of la Nueva Cocina Vasca, with Luis as the group’s patriarch. During their weekly dinners members showcased new recipes and techniques as the group discussed the future of the food they loved so dearly. Groups of food critics, cooks, and favored clients were brought in to taste and evaluate these new creations, and together, they began to form the language of the New Basque Cuisine.

“Luis has always been our guru,” says Juan Mari Arzak, chef of the eponymous Michelin three-star restaurant, long one of Spain’s most famous and important outposts of innovation. “He was the master of traditional cuisine, and he offered his full support to this group of chefs. Whenever there was a problem, there was Luis to help solve it.”

Armed with a new language to spread his message, Luis went on to open a series of restaurants that would unveil to the Spanish world some of the most sophisticated cuisine the country had ever seen. What he, Arzak, Subijana, and others created in the 1970s and 1980s didn’t just form the basis of a new style of cooking in the Basque Country—one defined by a deep respect for classic technique but with an eye toward the future—but in all of Spain, eventually inspiring the likes of Ferran Adrià and other young chefs who would turn the country into the center of culinary innovation in the twenty-first century.

Today, the Basque Country is among the most Michelin-dense regions in the world, but every galaxy starts with a single star, and the Basque’s first constellation belonged to Luis, who earned one in 1975 for his restaurant Gurutze-Berri.

In 1992, he and his daughters opened the Escuela de Cocina Luis Irizar, an intimate cooking school on the edge of the old part of San Sebastián, with a generous view of La Concha, San Sebastián’s famous crescent-shaped beach. With the worst of the Basque Country’s rocky past behind it, Luis and his family looked to pick up where they left off at Euromar.

As they began to equip a new generation of cooks with the lessons learned over a lifetime, the first wave of Irizar disciples spread out across the country, fomenting the revolution that Luis had sewn in 1967, winning their own loyal following, and earning for the man who had taught them a title still used by those that know the true history: el maestro de maestros.

The master of masters.

![]()

But it wasn’t just the masters who passed through Luis’s kitchen. In July of 2002, with the Basque culinary revolution already in high gear, he accepted an unlikely student into his summer course: a young, foolish, infatuated American looking to extend his lease in Spain.

I had come to Spain six months before to study at the University of Barcelona and promptly felt my world turned upside down. It wasn’t just Spain that I fell in love with, but an entire culture dedicated to the earthly pleasures of food and drink. Those were heady days, skipping class to ride my skateboard to the Boqueria to fill my backpack with the cheapest ingredients possible, then transforming them into meals decent enough to fill our apartment with people. Our dinner parties had menus that, like the guests themselves, spanned the world: sushi night, fresh pasta feasts, mole-and-margarita fiestas. Every cook has that moment when he or she recognizes the power of food to bring people together, and this was mine. The lesson hit twice as hard in this foreign land, with foreign faces and foreign tastes; every night was proof of food’s power to cut through color, creed, culture.

Up until then, I had taught myself to cook largely by reading my mom’s magazines and watching endless hours of chefs like Mario Batali and Ming Tsai after school on the newly launched Food Network. I converted my parents’ kitchen into a smoke-filled receptacle for my culinary failures, menacing Teflon and taste buds at every turn, but slowly I figured out how to sear a steak, fold an omelet, whisk a vinaigrette—just enough to impress my friends and woo a few love interests. But there were limits to my DIY approach to cooking, and I wanted to see what waited beyond a makeshift education. I went online and found a small but esteemed cooking school offering summer classes right next to the beach in the town of San Sebastián.

I had been to San Sebastián a few months earlier for spring break and fell hard for the convergence of soft sand beaches, shamrock mountainscapes, and dense clusters of bars and restaurants. I bodysurfed in the bracing pull of the Atlantic, drank wine in old plazas with pockets of young locals, tasted foods I didn’t know existed from glorious bar spreads, and barely touched a pillow for forty-eight hours. As the train pulled out of the station, I scribbled a few words in my journal before passing out: Come back soon. With a purpose.

But I was broke. Six months of decadent dinner parties and all-night benders had depleted the meager funds I brought with me to Europe. My roommate David Klinker agreed to join me in the Basque Country, and together we hatched a multipronged plan to raise capital. We bought cheap European cell phones from departing American students and sold them to the new wave coming in for the summer at a steep markup. We recruited deep-pocketed tenants to rent out the extra rooms in our apartment. In a particularly desperate moment, we took jobs at La Ballena Azul, a new carwash on the outskirts of the city. After a month of suds and cells, we made the nut and headed north.

In a class of Spanish cooks looking to take their interest in food to the next level, I was the lone foreigner—outmatched in kitchen skills and language capabilities, if not enthusiasm. My fellow classmates mostly seemed amused by my presence: by my marginal knife skills, by my Mexican-inflected Spanish, by the fact that David would wait outside the school entrance every evening with a bag of ice and a bottle of whiskey for sundowners. On one of the first days of class, we were left to clean piles of squid. Uninitiated in the finer points of cephalopod anatomy, I accidentally punctured the ink sack, turning my white jacket into a Rorschach test and the classroom into a laugh track.

But Luis went out of his way to make me feel at home in his school. When I’d show up for class, he’d announce my entrance—“¡el californiano ha llegado!”—and throw an arm around me. If he saw me mishandling a monkfish, he’d come by to gently correct my technique (“use the spine to guide your knife”). One day, after spending all night out in Pamplona drinking and all morning being chased by giant beasts down narrow streets, I walked into class late, disheveled, reeking of bull’s blood and bad decisions. Luis stopped the class, looked up from his perch by the stovetop and smiled: “Let me guess, San Fermín?”

For a man of his towering stature, he cut a warm, inviting figure: soft eyes, bushy mustache, a smile that scarcely retreats from his round face. He’s the grandpa you adored as a kid, the one with the bottomless supply of swashbuckling stories that left your mind racing for days. His desire to teach, to share with his students that great bank of knowledge he has accumulated over a lifetime of wandering the world, comes out in everything he does.

By the time I took up the toque, the day-to-day operations of the school were handled by three of Luis’s four daughters: Virginia and Isabel in charge of enrollment and administration, and Visi, who ran all kitchen and classroom operations.

Born in London during the Hilton years, Visi grew up cooking at her father’s side. Like her father, she spent her early years chasing the next lesson, cooking in London, then in Sevilla. Later, she joined him in the kitchen in Irizar Jatetxea, where Madrid’s power class came to eat New Basque Cuisine and debate the issues of the day.

I learned a lot that summer with Luis and Visi: that by adding olive oil in a slow, steady stream to a pan of cooked salt cod, swirling the pan in gentle circles, the fat will emulsify with the fish’s natural collagen, forming a smooth sauce—pilpil—that is to Basques what hollandaise is to the French; that a squid’s body (once carefully de-inked) can be cut into thin, ivory strips that look like rice noodles but taste purely of the ocean; that everything starts and stops at the market; that there are no recipes, only techniques and ideas; that certain contingents in the Basqueland may not have warm feelings for the central government, but their pride for the homeland creates some of the world’s most hospitable hosts.

Above all, I learned that I was hungry. Until then, I spent most of my college years dreaming of penning salty novels in a tiny tropical beach shack, but suddenly, all I could think about was the next meal. Where would it come from? What would it taste like? What were the steps I would need to take to bring it to life?

I had never eaten in fancy restaurants before. In general, I had tasted very little of Spanish cuisine, spending the little money I had in Barcelona on cooking and drinking (the main meal I ate out in those days was Burger King’s two-for-one Whopper special). The dishes we created in class, classics of the Basque canon, were the closest I had ever come to haute cuisine, and they quickly and irrevocably changed my idea about the alchemy at work in the kitchen: stubborn off-cuts of animals transformed into tender, gelatinous stews through slow, steady cooking; seasonal vegetables treated with the gentlest forms of heat and seasoning possible; fish and seafood of every imaginable permutation: salt cod tucked into weeping-soft omelets, squid bathed in puddles of its own ink, fat fillets of white fish blanketed in a warm sauce of roasted peppers.

The little I managed to eat outside of school opened my eyes even wider. A pintxo bar in full bloom is a creature of arresting beauty—where oil-slick anchovies and golden-fried croquetas and stuffed piquillo peppers like puckered red lips could arouse even the most prudish passerby. Spread out in the open, covering every square centimeter of bar space in a tapestry of plants and protein, they suggest a food world of infinite possibility. I could feel myself slipping ever deeper into its possibilities.

My mom, perhaps sensing I might never return, convinced a neighbor to hire me as a fry cook at his seafood institution in downtown Raleigh, a development which she shared via e-mail. (Subject: Good News!)

By the time I pulled myself out of San Sebastián, destined to spend the next few months frying catfish and hush puppies, the pioneering chefs who had passed through Luis’s school were well on their way to transforming San Sebastián and the surrounding region into one of the most important food destinations in the world.

And I was well on the way to my own transformation.

![]()

Spoiler alert: I didn’t turn out to be a chef. It wasn’t for a lack of trying, though. I took the lessons of Luis and Visi back with me to North Carolina, where my family lives, tried to employ some of the savvy cooking that the father-daughter team imparted upon me in my new role as a grease jockey. But as it turned out, it’s hard to find hake chin in Raleigh, and the eaters of the Deep South prefer red-eye gravy to squid ink. The old battery of cooks, most of them ex-convicts with cornbread hearts and buttermilk souls, took to calling me “tender hands,” due to the fact that I was unable to reach directly into the fry basket and remove incinerating bits of fried shrimp and oysters with my uncallused mitts. I lasted a few months before heading West to finish my college career.

FOR THE BASQUES, IT’S A BIRTHRIGHT TO EAT AND DRINK AS WELL AS POSSIBLE.

![]()

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

During my last year at UCLA, I helped open a café in Brentwood, the kind of earnest eatery that sells eighteen-dollar mixed green salads to rich Angelenos. Also the kind of place that packs two cups of heavy cream and four cups of sharp cheddar into a serving of “organic” mac and cheese. The first time I was left in charge of the kitchen, a well-intentioned young cook from Mexico tossed a handful of chilies into a massive pot of roasted vegetable soup, thinking they’d add a gentle glow. Turns out they were a mutant breed of habaneros, and the chef berated us both for days. I got tired of Los Angeles, tired of trudging back and forth between the library and the kitchen, tired of being tired.

I graduated, moved to Chile, lived in a cabana close to the beach north of Valparaiso smoking lots of pot and cooking elaborate meals for anyone who would come over. One guest was a young woman who cooked on a boat in Patagonia. Weeks later she called and offered me her job. The boat took small groups of passengers on weeklong trips through the fjords and archipelagos of an impossibly lonely and beautiful stretch of earth. I cooked elaborate meals for them—mostly based around fish bought from the old fishermen who rowed those majestic fjords.

When summer drew to a close, the owner of the boat recommended me for a position running a kitchen at a resort being built nearby. For my tryout, I cooked the managers a fish dish I learned from Visi and they gave me the job. Seven miles of virgin Patagonian coastline fringed with old-growth forest, all part of a high-end eco resort years in the making. I signed on to run the kitchen, with a close friend growing the food and raising the animals I would cook. An incredible project, but one that would take years more to develop—years I didn’t have to spend on a cold, wet coastline in Patagonia. (Years later, I’d watch in shock as Bourdain dined on the dishes of my replacement, overlooking the same wild beach I could see from my cabin, on an episode of No Reservations.)

All along the way, I wrote. Mostly bad poetry or hip-hop lyrics or tortured short fiction. But when I decided that maybe I wasn’t cut out for a life behind the stovetop—that professional cooking demanded a level of physical exertion and geographical commitment I wasn’t prepared to give—I needed a new source of income. The first publication to pay me for my words was a magazine distributed on college campuses called Student Traveler. I wrote for them the most interesting story I knew: about being the only foreigner in a Basque cooking school.

Seeing my name in print felt better than seeing my face in the mirror after a long night of searing salmon and drinking Greyhounds. I also came to accept that I was better writing about food than actually cooking it. My career as an aspiring chef came to a sudden halt, and my career as an aspiring writer, while many years from being an actual career, lurched forward—both built on the back of that same half-moon slice of heaven, San Sebastián.

![]()

Somewhere shortly after my first paid writing gig, the food world exploded. The first decade of the new millennium saw a tidal wave of unprecedented interest that infiltrated every level of the culinary world. Chefs became the new rock stars, complete with tattoos and groupies. A new class of television and print media emerged to feed the growing appetites of the food-obsessed while online forums and bloggers cataloged every calorie consumed in pursuit of the perfect meal. And the travel world began to undergo its own transformation. Suddenly, the same people who once traveled to Spain to see the works of Gaudí now came to taste the works of Adrià.

In this delicious new world, the Basque Country was born to be a star. Towering restaurants of avant-garde adventurism, concentrations of bars proffering small bites and bonhomie, a reenergized class of old-world artisans now feeding a new-world audience—it had all the ingredients of a culinary uprising. In short order, the world’s new class of gastronauts came pouring into the Basque Country.

I returned more than a few times myself over the years. With glossy magazines paying the way, suddenly I could afford the towering temples where once I only window-shopped. At Arzak, the first restaurant in Spain to receive three Michelin stars, father-daughter team Juan Mari and Elena served me bonbons of foie, packages of apple and pig’s blood wrapped in seaweed, hunks of lobster scattered atop a video screen with a seaside scene on loop. At Mugaritz, I ate Andoni Luiz Aduriz’s edible potato stones and braised cod tripe and charcoal-coated veal, dishes that combine the modernist techniques favored by Spain’s new guard with a heavy dose of naturalism to create a cuisine that is both beautiful and befuddling. In Bilbao, which writers and chefs in this country correctly call Spain’s most underrated food city (overlooked because it lies in the skirt folds of its sexier sister down the coast), I went on pintxos crawls that alternated bites of extraordinary imagination with ones of sublime simplicity.

Most remarkable of all is Etxebarri, in the mountain village of Axpe, where Bittor Arguinzoniz has created a restaurant like no other in this world—one fueled entirely by the flames of the hearth and his own relentless pursuit of perfection. Everything from the smoked goat butter to the just-cooked red shrimp stands as a resounding reminder that the beauty of Basque cuisine stretches well beyond pintxos and pyrotechnics. If forced to choose just one restaurant to eat at for the rest of my life, Etxebarri would be it.

At first glance, the lines between these modern meccas and the man I called maestro might not be so obvious. Ask the new guard of gastronauts who come to the Basque Country expressly to eat about the name Luis Irizar and they’ll likely just keep chewing. Most Spaniards don’t know the name either. Such is the nature of the teacher, bound to be forever overshadowed by his students. But Luis was more than just a talented teacher; he was a catalyst.

In the modern culinary world, the actions of a few powerful forces can have a profound impact over the years as the effects travel outward. In 1966, a rock landed in the center of the great Basque sea. Fifty years later, its ripples continue to work ever outward.

The first ripple, the one that set into motion dramatic changes in the world of Spanish fine dining, came from the mustachioed phenomenon named Pedro Subijana. From his education at Euromar, he would go on to teach his own students: in the classroom, on television, and in the professional kitchen. Since taking the helm at Akelarre in 1975, it has been a constant presence on the list of the world’s best restaurants—a perfect bridge between the classical, technically refined cuisine of Luis and the first wave of new Basque chefs and the more radical innovators who would come later on.

In Getaria, a small fisherman’s town between San Sebastián and Bilbao, I encounter another ripple in the sea, Pablo Vicari, class of 2003. He now runs the kitchen at Elkano, a family-owned restaurant a few steps from the Atlantic. This is no small charge: Elkano is considered by some to be one of the world’s finest seafood restaurants. Started in 1964 by Pedro Arregui and now run by his son Aitor, Elkano is best known for its heroic servings of whole turbot and sea bream grilled over oak.

Pablo hails from Argentina, but came to the Basque Country and fell in love with Luis and his school. “I learned everything I know about being a cook from the Irizar family—not just how to do things well in the kitchen, but to do them with respect and humility that have characterized Luis’s career.” The recipes of Elkano come from the Arregui family, pioneers of the open flame, but you see in Pablo—in the way he works the fire, in the care he puts into plates of barnacles and anchovies and lobster—the other side of Basque brilliance, not a burning desire for innovation, but a religious respect for perfect product and perfect technique.

Karlos Arguiñano walks the vines at K5, his txakoli vineyard above the Atlantic.

Matt Goulding

One of the ripples wasn’t a ripple at all; it was a tidal wave, and its name was Karlos Arguiñano. One day I make my way up to the foothills of Zarautz to see the most famous student to pass through the School of Irizar.

For many people around the world, including millions in Latin America who watch Karlos every day, Basque cuisine, if not all of Spanish cuisine, begins right here. “When I started on television, I thought, okay, I’ll give it six months until people get tired of me. But it was the opposite: every month more people were watching.” Six thousand episodes, eight thousand recipes, and fifty-five books later, Arguiñano is one of the most influential chefs on the planet, responsible for inspiring the daily creations of countless home cooks.

Karlos shows me around the studio where he films all episodes of Karlos Arguiñano en Tu Cocina. He runs around the kitchen, playing with puppets, inspecting ingredients, dispensing one-liners with a comedian’s ease and timing. Later, he takes me up to his vineyards, where he grows the most Basque product of all: txakoli, the dry, effervescent wine that lubricates a high percentage of the region’s eating and socializing. We drink cold streams of K5, the only txakoli served in all of the Basque Country’s three-star restaurants, while Karlos cooks us fried eggs with jamón and tells jokes about the guy who drowned in a cider tank. This is the Arguiñano that most of the Spanish-speaking world knows: frenetic, hilarious, unstoppable.

Not everything that Karlos cooks is Basque—at some point, you exhaust the encyclopedia of dishes. And given the controversy surrounding the Basque Separatist movement, he’s always been careful not to make Basque pride part of his television persona. But deep down, he bleeds for his homeland. “You have so many things that make this region so great. The climate, the sea, the proximity to France, to Navarra for vegetables, to the Rioja for wine. The hundreds of gastronomic societies scattered throughout the region. In a small space we have a lot of a gastronomic life. You know what they say? The Basques screw little but they eat a lot.”

Karlos was sixteen and enrolled in a local cooking class (“forty women and me—they all thought I was gay”) when he saw that a new culinary school had opened down the road, run by the ex-chef of the London Hilton. He didn’t have the money for the school, but Luis accepted him anyway, an act of generosity that still visibly moves Karlos to this day. “It’s hard to make money being one of the good guys. You end up making it for everyone else. Luis has always been an example of that.”

Karlos formed a part of the Triumphant Generation, the first class of Irizar students that would move on to reshape the Basque culinary landscape in the decades to follow. “He was an extraordinary professor, someone who transmitted everything he had seen and done to his students.” Luis taught them not just how to clarify stocks and emulsify sauces, but how to handle themselves in the world. “Luis was a magnificent cook, a fantastic professor, but an even better person.”

Back in the center of San Sebastián, I do a few laps around the city, eating at dozens of pintxos bars and restaurants. Some of these places—Astelena, Txubillo, the Michelin-starred Kokoktxa—are run by Irizar alums. Others are not, but wear the mark nonetheless. The terrines of foie, the seafood gelées, the plates of wild game all carry more than a few strands of Irizar DNA. The chefs behind these creations may not have trained down the street. Some may not even know the name. That is how the ripple works. It hits you, whether or not you know it.

If you find yourself in the Parte Vieja of San Sebastián eating hake chin, or in the center of Bilbao feasting on fattened duck liver, or in a wine bar in SoHo sipping K5, it’s safe to say the ripple has hit you too.

![]()

I’ve passed by the school countless times over the years, peeked through the windows into the sunken classroom to see a new wave of young students dressed in their crisp white jackets, boning turbot or braising oxtails or sweating out a pastry lesson. One day, I see a group out front smoking and I ask them how class is going. “Man, I love Visi, but she’s tough. The other day I got in trouble for overcooking asparagus.” How about Luis? “He comes by in the mornings and likes to watch us cook. Seems like good people.”

But I can never bring myself to walk down those stairs. I was only there for part of a summer, and that was fourteen years ago. Will they remember me? Do they care? It’s like meeting your favorite musician or author—someone who has impacted your life so deeply without them even knowing it. What do you say?

Instead, I take the easy way out. I send an e-mail from my rented apartment a few blocks down the road, tell the Irizar family who I am and that I’d love to say hello if they have a free moment. Virginia writes back immediately: “Of course we remember you. Luis would love to see you while you’re in town. Come by tomorrow at eleven a.m.”

The last time I saw Luis, I was twenty-one years old, on my way to an underwhelming four-year career as a wandering cook. He looks the same: same quiet elegance, same prodigious mustache, same endless smile.

We talk for a while downstairs in the school’s office while students in the classroom behind us take in a lesson on fish fumets. The smell of monkfish and root vegetables fills the room.

“What have you been up to all these years?” he asks me. I give him a condensed rundown, tell him about my time as a fry jockey and a boat cook, that I married a Spaniard and am writing a book on his country. “You don’t say. And that all started here?” He stares out the window, scanning something on the horizon. He’s been a part of hundreds of genesis stories, but this one, admittedly, has a few unexpected twists.

Mostly, though, we talk about his life, about the years on the road, raising a family while accumulating an encyclopedic understanding of classic European cooking. When he tells me about those tough first years running contraband and scraping by in an industry threatened by famine, he lowers his voice and leans in—a habit you’ll find with older Spaniards when they speak about the Franco years. But when it comes to the kitchen, he’s as animated as I remember him: eyes wide, hands darting here and there, plucking anecdotes from the bookshelf of his mind. “All I ever wanted to do was share what I was fortunate enough to learn.”

He doesn’t get around like he used to, but he still loves to walk the old streets of his home city and pay his respects to the cooks he and his family helped shape. Luis and Visi take me to one of their favorites, Casa Urola, an institution in the old part with the typical two-pronged approach of good Basque restaurants: pintxos on the bar, ready for immediate consumption, and a longer menu of prepared dishes for those sitting down for a full meal. It’s a place I’ve walked by a dozen times without ever noticing—a testament to the top-to-bottom potency of this eating town.

Visi goes back into the kitchen to have a word with the chef and soon the plates come rolling out. First, guisantes lágrima, teardrop spring peas studded with slices of raw wild mushrooms and a veil of acorn-fed jamón. The tiny peas pop like caviar against the roof of my mouth, releasing little depth charges of spring across the palate.

“The Basques take eating more seriously than anyone I’ve met in my travels. They believe it’s their duty to eat as well as possible,” says Luis. “And they never get tired of it. Even the old couples still go out on tapas crawls.”

“Women set aside a night each week to go out with their friends,” says Visi. “The men may have their societies, but we go out and eat and drink on our own too.”

Years ago, on one of the early episodes of No Reservations, Visi took Bourdain out with her female posse and they all ate a ton and got pretty loaded. In a separate scene, Luis brought him to his local society, one of the 1,500 all-male gastronomic societies that dot the region, places where men gather to cook, drink, and sing homages to the Basqueland. Luis taught him how to make hake with salsa verde, a Basque classic, in the heavily accented English of his Hilton days.

“How is Anthony doing these days?” asks Luis.

The chef brings out a plate of farm eggs scrambled so softly they’ve barely coagulated, covered in thin shavings of St. George’s mushrooms, one of the many foraged fungi that drive Basques wild in the spring and fall. They have the impact of truffles on the loose scramble, pulling us all in close to the plate with hunks of bread for mopping. Visi pours another round of txakoli.

We talk about the latest crop of students—a group that has started to skew more international as the Basque reputation has grown. (The school’s waitlist swells with each passing year.) Visi has worked sensibly to evolve the school to fit the times, incorporating the types of lessons that the modern student wants to absorb before heading out into the restaurant world: how to thicken a sauce with xanthan, cooking sous vide, folding in flavors from the global pantry.

Luis, though, belongs steadfastly and proudly to a different era, one where everything starts with product, where surprise isn’t an ingredient, where a bowl of peas sure as hell better look and taste like a bowl of peas. He can’t tell you how the big names today spherify olives and turn liquids into powder, but come over for dinner and he’ll make you a liebre a la royale that would make Escoffier weep. (About the time he made Arzak and a group of French chefs wild hare covered in blood sauce at Arzak’s house, Luis says proudly: “They said it was the best they’d ever had.”)

The master of the masters, with an admiring student.

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

The chef plants a plate of kokotxas, hake chin, in the center of the table. Luis sits up. “This is one of the most important plates in Basque cooking.”

Visi, the perennial professor, breaks it down: “You make it with olive oil and a pinch of chili and a splash of txakoli to temper the oil. You always make it with the skin side down with a pinch of salt. In just a minute the gelatin will start to release.”

I ask them why you never find kokotxas outside of the Basque country. “Let’s hope it stays that way,” says Luis, growing increasingly animated with the wine. “We don’t want the price to go up. It’s like jamón. If the Americans ever find out about true Spanish ham, there won’t be any left for us.”

“We have an inferiority complex here in Spain,” adds Visi. “We’re possessed of this idea that other people’s food is better than ours. We always stress to our students that they need to care about the local culture, they need to defend great producers and old traditions. Nobody wants to go to a city where the food doesn’t have its own identity.”

Listening to her talk brings me instantly back to the classroom: strong jaw and fixed eyes and sharp hand movements, with a gentle urgency that tractor beams you in and a generous smile, the same one that her father has, that opens you up to whatever message she’s delivering. I can see it doesn’t just work on me; whenever Visi talks, Luis closes his eyes and nods his head emphatically.

Subijana and Arguiñano and half a dozen other Irizar alumni may have gone on to be titans of the culinary world, but Visi will always be the most important student to emerge from the school of Luis. Of all the ripples Luis has left behind, none matters more than Visi, the one who carries on the Irizar name, who is responsible for teaching a new generation how to handle themselves inside the kitchen and out. “She’s me. She’s my daughter, but she’s always been me.”

A plate of candlestick white asparagus lands on the table, one of the region’s most treasured ingredients, served with olive oil and bread crumbs. Luis sees the scantily clad plate and gives it a nod of approval.

“What matters most to me is that Basque cuisine remains Basque, that it doesn’t fuse with Japanese or South American or anything else. That it remains ours.”

Despite his loyalty to his home, as the conversation wanders across the Iberian landscape, Luis admits that he’s worried about the future of Spanish food. “We’ve gone too far. There used to be an invisible line between the world of restaurant food and industrial food producers. These are the ingredients we use, these are the ones they use. Until one day someone crossed that line.”

Visi sees him getting worked up and puts her hand on his forearm. “Come on, Pop. You shouldn’t worry so much.”

“What? You know it’s true! One day soon you’ll be eating a pill that tastes like a raspberry instead of an actual raspberry. I won’t be around to see it, but when you taste it, think of me.”

The last dish of the day comes out of the kitchen: torrijas, Spain’s lavish take on French toast. Urola’s version is stunning, so outrageously soaked with cream and egg that it tastes like flan.

I pass Luis a fork and gesture toward the dessert, but he waves me off. “You need it more than I do.” By now, Luis has had his share of txakoli and his eyelids are slowly starting to shutter. He likes to head home in the afternoon, time enough to work in a nap before evening sets in.

He pays his respects to the chef. “Better than ever, my friend. Thank you for taking such incredible care of us.”

He turns to me, sticks out his hand, shakes mine like he’s shook so many before. “Best of luck to you, californiano.”

The owner holds the front door open. Luis puts on his hat and grabs Visi by the arm and the two of them step out of the restaurant and into the orange light now bathing the narrow street, disappearing into the crowds that wander the old part of San Sebastián in search of the next bite.

Grill Gods

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

With all due respect to Argentina, Uruguay, and the Deep South, the grill culture of northern Spain may be the greatest on earth. From the mountain villages of the Basque Country to the coastal hamlets of Asturias, you’ll find asadores, family-run restaurants powered by fire and protein, where meals consist of flame-grilled meat and fish, a token vegetable or two, and plenty of local vino. These four destinations are where world-class ingredients and unimpeachable technique conspire to ruin you for all other grilled food going forward.

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

Bodega El Capricho, León

RAISING THE STEAKS

Eating at Bodega El Capricho will be the most intense meat experience of your life. José Gordón is a man possesed by the pursuit of the perfect steak, a journey that starts by raising his own bueyes (oxen) on a special diet of grain and grass, then drying aging primal cuts of meat based on the age and race of the animal. A meal at El Capricho starts with ruby veils of raw aged ox loin, then moves on to cecina (dried beef cured and aged like jamón), ox blood morcilla, and an outrageously good tartare. But all of that is a minor prelude to the main event: chuletón de buey, massive rib steaks, cooked over oak with nothing but coarse salt until charred on the outside and barely warm throughout. The meat packs deep concentrations of umami and mineral intensity and a rim of dense, yellow fat that tastes like brown sugar. Warning: It will be hard to go back to regular beef after El Capricho.

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

Matt Goulding

Elkano, Getaria

THE TURBOT KINGS

Perched above the Atlantic in a small coastal village pinched between Bilbao and San Sebastián, Elkano is best known as an asador de pescado—a family-run restaurant with a hyper focus on grilled fish and seafood. The main attraction is rodaballo, wild turbot cooked whole over charcoal—a technique perfected by Elkano’s founder Pedro Arregui in the 1950s and continued today by his son Aitor and chef de cuisine Pablo Vicari. After a heavy shower of coarse salt and a twelve-minute ride on the grill, the turbot is served whole at the table, then divided into its various constituents—dark, fatty back sections; light, meaty fillets; gelatin-rich ribs that leak juice down your forearms. The end product eats like an essay on the astounding potential of the sea, a range of tastes and textures you didn’t think possible in a single fish.

Matt Goulding

Etxebarri, Axpe, Basque Country

MAN ON FIRE

“In the flames of the fire lives something that can help ingredients reach their fullest potential.” These are the words of Bittor Arguinzoniz, high priest of the low flame who abandoned his job as a forester years ago to create one of the world’s most astounding grill shrines. Everything—from the homemade goat butter to the caviar-sized spring peas to the grass-fed Galician beef to the apple tart—gets hit with smoke from wood the chef chops right outside the back door. But this isn’t the hard smoke of a pitmaster; this is the delicate finesse of an artist in full control of every bite that passes into the dining room. Ask ten of the best chefs from around the world where they’d eat their last meal on earth, and half would tell you here, at the high-mountain altar of Etxebarri.

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

Güeyu Mar, Playa de Vega, Asturias

FISH TALES

On a quiet stretch of Asturian coastline, sandwiched between the Cantabrian Sea and the Camino de Santiago, Güeyu Mar at first blush looks like a chiringuito, a mellow seafood shack, but inside, nothing about husband and wife Abel and Luisa’s work is the least bit laid-back—not the remarkable wine list or the specialized hand-cranked grills or the constantly rotating, individually sourced menu of fish and seafood. Depending on the day, your meal might begin with tiny, candy-sweet quisquilla shrimp and grilled oysters with caviar and conclude with any of half a dozen whole grilled fish: from the pull-apart flakes of grouper to big-bellied king fish rippled with fat and gelatin. Afterward, waddle your body down to the nearest stretch of sand for a siesta.

Matt Goulding

THE LONG MIGRATION

Of all the rare, exceptional seafood pulled from the waters of northern Spain, baby eels may be the most revered. Born near Bermuda, they make the long, slow migration to Northern Spain in search of freshwater rivers along the Basque coast.

SPARE NO EXPENSE

Spaniards pay top euro for delicate marine treasures—the Basques most of all. Like many of Spain’s lavish and rare foodstuffs, angulas are most popular during the Christmas season, when they command up to EUR 1,200 a kilo.

SWEET MEETS HEAT

Angulas are usually served a la bilbaína, cooked in crocks with olive oil, sliced garlic, and spicy guindilla—a foil to their delicate oceanic sweetness. A single serving, costing up to one hundred euros, could have more than three hundred baby eels.

SOCIETY’S EELS

You’ll find the dish on high-end menus across the northern coast. There may be no better place to consume them, though, than in a Basque gastronomic society, where locals gather to drink and sing and cook rare delicacies from the sea.