![]()

The Trap

The sun rises never the same. This is the Mediterranean, highway of wealth and wisdom, and beneath her surface stirs a silver storm of fish. A great migration, hunted.

With forty men on its way to forty more, the Bermudez cuts up the coast under the red roof of first light. Antonio González, hunched against the hull, takes a fisherman’s breakfast of cigarettes and silence. Dressed for battle—camo jacket, camo hat—he has spent thirty-seven years of his life on this boat, one of a band of brothers that works these waters. Álvaro, Antonio, Miguel, Pepe, José: nearly two centuries of fishing between the brothers González.

“It always begins this way,” Antonio says, “always with the silence and the smoke.”

The engines whimper as the destination nears: a wall of nets, a maze of mesh and nylon meant to break the magnificent motion beneath. One arm of the trap stretches toward Africa, the other toward Spain. Zahara de los Atunes, its sunglass shops and mojito bars, stands starboard, motionless. The men begin to stir—stretching, stripping, shaking daybreak from their bones. A small flotilla bobs in the distance.

A crew of four, the youth of the Bermudez, step into their neoprene skins: the scuba team, the scouts, the ones who will take stock of what moves beneath.

As the boys go under, Captain Pepe surveys the sea. Fifth generation, sun on his skin, salt on his breath. A man of action, he of frosty mustache and granite jaw, wary of the foreign presence on his watch.

“Doesn’t look good,” Antonio whispers to himself. He’s right: cloudless, light wind, but the sea swells and pitches the boats as the captain’s jaw tightens like a guitar string.

The scouts resurface. The youngest, Gonzalo, beams. “They are there!” he says. “The tuna are all there, just waiting for us. Today, luck is on our side.”

The boat’s engines warm again, a raspy throat clearing. Antonio puts out his cigarette, the captain blows a whistle, and thus the almadraba, one of the world’s most ancient fishing traditions, begins.

When the Phoenicians touched down in Cádiz over three thousand years ago, they found a small spit of land jutting out into the sea, a strategic commercial and military base at the mouth of the Mediterranean. In the millennia to follow, Romans and Greeks, pirates and pioneers, kings and conquistadores would impose their will on the peninsula, but Cádiz waited out each visitor like a batch of bad houseguests. Today, Cádiz is a city of 120,000 residents and the oldest continuously inhabited civilization in Western Europe.

On a clear day, you can see Africa from the tip of Cádiz. The province is the southernmost part of Spain, nearly as far south as Europe goes, and the city wears its mix of Moorish, Jewish, and Christian history conspicuously—in the maze of narrow, confounding streets that recall Marrakesh, on the smooth curves and sharp angles of mosques and churches, in the spices and dried fruits and nuts that adorn the food of the region. Despite its history and stature, Cádiz doesn’t take itself too seriously. Its citizens possess a quiet confidence that recognizes they must have done something right to end up here. Indeed, it’s the name that surfaces time and again when the rest of Spain debates its favorite corners of the country.

When people talk about Cádiz, though, they’re not just talking about the city itself, but the constellation of coastal towns, hilltop villages, and inland islands that populate the peninsula. There is Jerez, where the dapper Andalusian gentleman shakes off his siesta with a glass of fino and a plate of jamón. In Sanlúcar de Barrameda, a sun-bleached city known best for its Manzanilla and the horse races on its beaches, you will find the finest fried dish in all of Spain, the tortillita de camarones, a lacy amoeba of tiny shrimp and olive-oil-crisped batter served in bars and freidurías around the region, but nowhere better than Casa Balbino. And if you make it to Vejer de la Frontera, a staircase of whitewashed houses and serpentine streets and quiet plazas of cinematic beauty, you risk never leaving.

A crew of fisherman row into the teeth of the tuna trap.

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

This isn’t exactly the southern Spain most people know—Sevilla, home of flamenco and matadors and oversized cathedrals, is an hour to the north—but it’s not far off. Life moves slower down here than it does almost anywhere else in Spain. Beaches, among the finest in the country, cradle bronzed bodies in their soft sands six months a year. People sit for hours in the amber afternoon light of the smooth tiled plazas, happy enough to feel the sun on their skin and the wine in their bellies. One afternoon, I stepped into a restaurant to ask directions and stayed for three hours, watching bullfights and bullshitting with the old men drinking beer at the bar.

As its oldest city and southernmost gateway, Cádiz has been on the front lines of Spain’s food culture for millennia. This was one of Spain’s earliest wine regions, started with grapes brought over by the Phoenicians in 1000 BC. Today, Palomino grapes for fortified wines, brandy, and sherry vinegar cover the hills and fill the bodegas around Jerez. The gaditanos (the people of Cádiz) have long been recognized as masters of fried food of all stripes, especially pescaito frito, small, oily fish eaten spine and all. And an entire culture of pastries and sweets developed in the convents of the province, nuns long a major driver of Spain’s traditional food culture. The flan-like tocino del cielo, one of Spain’s most enduring desserts, came about as a way for the nuns to use the egg yolks from sherry producers, who only needed the whites to clarify their wine.

But no food has done more to shape the history and the economy of the region than Thunnus thynnus, the Atlantic bluefin tuna, today considered the most valuable fish in the sea. Engravings and cave paintings of the bluefin date back to 4000 BC. Hippocrates wrote of the importance of bluefin, as did Aristotle and Pliny the Elder. Phoenician coins in early Hispania came with two tunas engraved on the face.

For most of tuna’s long history in Spain, its principle value has been in by-products. The Phoenicians set up centers to make Spain’s first salazones, salted and dried tuna products, which they exported to its colonies throughout the Mediterranean.

To catch the massive schools of tuna migrating from the Atlantic, where they fatten up in the winter, to the Mediterranean, where they spawn in warmer waters, the Phoenicians developed elaborate net traps and positioned men on top of towers along the coastline to spot the incoming schools. Later, the same technique would spread elsewhere in the Mediterranean—to Portugal, Morocco, Sicily.

The Romans continued the tuna-hunting traditions popularized by the Phoenicians. They still made salt-cured fish, but placed even greater importance on the oil extracted from tuna’s fermented flesh, skin, and innards, called garum, one of the world’s first fish sauces. Wheat, grapes, and olives, the heart of Spanish cuisine, have been at the center of its economy since before Christ, but it was garum that made the Iberian Peninsula the most valuable corner of the Roman empire. In the centuries to follow, the focus of the catch evolved with the times and tastes of those who did the fishing, but the tradition of trapping migrating bluefin in the spring has continued more or less uninterrupted for three thousand years.

Today, the almadraba takes place in four separate communities along the Costa de la Luz east of Cádiz: Barbate, Conil de la Frontera, Tarifa, and Zahara de los Atunes. It takes fishermen two months of work under water to set this elaborate trap, another two months to take it down. In between, six weeks to catch as many tuna as the year’s quota will allow.

Phoenician fishermen would recognize the system used today by Spain’s bluefin hunters: the wall of mesh net—ten thousand feet long, one hundred feet deep—set up to halt the massive migration; the labyrinth of narrow halls and holes and hard angles that lead the fish ever-closer to their captors; above all, they would recognize the cuadro, the grouping of boats in the final pool of this serpentine system, where each day’s school of tuna meets its demise.

The Hunt

The fish don’t see it coming. The females swim on their sides, steely skin to the sky, sowing the water with millions of eggs. The Spaniards call the discharge a fresa, a strawberry, and the fruit grows best in these warm waters.

Fat from the frigid tides of the Atlantic, they hurtle toward the Mediterranean like a clip of silver bullets. A wall breaks their migration, funneling the fish into the esophagus of a giant digestive system, churning them forward from one compartment to the next until they reach the final bowel. Panic takes over in this web of deceit, but the only way out is up.

The captain’s men are all too happy to lend a hand. A small army clad in blue and orange stands at attention. A whistle signals the levantá and the lifting of the final net begins. As the boats inch ever closer, the net grows ever smaller, the space between life and death collapsing on itself.

The boats are one hundred meters away from each other with nothing but blue sea and frosted tips between. Men muscle the web and speak to each other in tongues. Cranes and metal hooks, the only modern flourish, reel in the nets like a giant fishing rod.

Seventy meters away and still nothing stirs. “You sure they’re down there?” one says. “You sure it wasn’t your shadow you saw?”

Forty and closing. “Let’s go, let’s go! Keep it coming!”

Thirty meters. Across the vanishing space a boat of Japanese men hold cell phones to their ears. Buyers, inspectors, arbiters of quality, the almost-invisible hand of the almadraba. They don’t set the trap, but they move the nets.

Twenty. “Iza! Iza!”

And then, suddenly, the sea explodes. A great churn bubbles violently to the surface like a pot of milk boiling over. Colors change rapidly, from blue to white to silver, as a mass of bodies breaches the surface, frantic in the shrinking space, searching for a way out.

“Imagine a fire in a soccer stadium,” a fisherman says, “and only one exit.”

Now imagine it without an exit.

Bluefin tuna was not always the king of the sea. For the better part of the twentieth century, it was considered a trash fish, so dark and pregnant with fat that fishermen around the world would catch it for sport and throw it back into the water. Sasha Issenberg, in his exceptional book The Sushi Economy, writes about an annual deep-sea fishing competition off the coast of New England. At the end of the day, when the winner had been crowned, hundreds of tuna would be sold off to cat food companies or trucked out to holes in the earth and buried en masse.

Despite the importance of salted fish and fish sauce in the economies of early Spain, by the twentieth century, bluefin no longer carried the same value it once did. A 1933 documentary of the Barbate almadraba shows a process nearly identical to today’s: the same network of nets, the same kind of hard-scrabble fishermen wrangling the catch by hand. It’s not until the tuna reaches shore that the process diverges: the heads, fins, skin, and organs were sundried, then steamed, then pressed for oil used to make soaps. The flesh was salted and dried to make mojama, or boiled and packed into cans with olive oil and shipped across the Mediterranean to Italy. There is only so much value in canned tuna and fish soap: In 1933, a 150-kilogram tuna was worth about 150 pesetas, roughly half a cent per pound.

The Japanese changed all of that. Sushi culture took shape in the Meiji era, when cooks fermented fish in seasoned rice for months at a time, extending indefinitely the life of the country’s primary source of protein. Modern sushi, Edo-style sushi, was born in the mid-ninteenth century, just as Tokyo was rising to prominence as Japan’s new capital. With fresh fish more readily available, cooks traded the deep funk of fermentation for freshly cooked rice, layering slices of the day’s catch—eel, mackerel, halibut—over the top with a swipe of soy for seasoning and a dab of grated wasabi to kill off bacteria. Sushi was street food back then, a few bites of nigiri used to tide over passing pedestrians before they made it home for dinner.

THE SPACE BETWEEN LIFE AND DEATH COLLAPSES ON ITSELF

![]()

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

Still, tuna was considered a lesser species by Japan’s elite, a bluefish with too much fat for their refined palates. They left it for the lower classes, favoring lighter white fish instead. But as Japan’s sushi culture deepened in the wake of World War II, the country’s palate changed with it. Japan, long a nation of pescatarians, had developed a taste for meat, and not just any meat: deep-fried cutlets of pork, charcoal-grilled skewers of odd chicken parts, and, of course, wagyu, the magnificently marbled beef revered in the world’s upper culinary circles. All have one thing in common: fat, an ever-increasing feature of a diet long considered to be among the world’s healthiest. And nothing in the sea has more fat than the big-bellied bluefin tuna.

By the 1960s, with domestic supplies dwindling, the Japanese began to scour the globe in search of bluefin. In the 1970s, Akira Okazaki, an executive for Japan Airlines, worked for the better part of the decade developing an advanced refrigeration system that allowed the Japanese to buy cheap bluefin in areas of abundance—Nova Scotia, New England, the South Pacific—and ship them back to Tokyo in near-perfect condition. The world’s global food economy was born. Thirty years later, bluefin forms the heart of a sophisticated system of buying, dividing, auctioning, portioning, and distributing: Tunanomics.

The tiny coastal towns of Cádiz comprise a central cog in this sprawling tuna machinery. After reaching peak production in the 1930s, the almadraba suffered in the wake of the war, and factories in Barbate and beyond, vital to the coastal economy, began to shutter. But as the Japanese continued to search for ways to satisfy the country’s growing appetite for fatty tuna, they found in the Costa de la Luz a seemingly inexhaustible supply of the fish they valued most. By 1990, emissaries for fish trading companies in Tokyo set up shop in Barbate, giving new life to an ancient culture that stood on the brink of extinction.

Spanish cooks might not have valued bluefin enough to pay top dollar for its meat, but the Japanese did. Between 1970 and 1990, fishing for Atlantic bluefin rose 2,000 percent, while the price for tuna exported to Japan rose a staggering 10,000 percent. A single large bluefin typically sells for anywhere between $2,000 and $20,000 in Tokyo, but occasionally an outlier will command an unthinkable price. In 2013, the owner of a sushi restaurant chain in Japan paid $1.76 million for the first bluefin of the New Year.

To give you a better idea of how Tunanomics works, let’s follow the fish. On the morning of May 12, 2015, the Barbate crew netted 159 bluefin tuna from the morning session. Of those tuna, the Japanese bought 83, with their inspectors on hand to maintain quality control during every step of the process—from the decks of the boat during the levantá to the docks of the Barbate port during the butchering.

After being cleaned and quartered, the tuna go directly into a super freezer. Within eighteen hours, the day’s haul will be frozen to -60˚C, at which temperature they can survive without any discernible loss in quality for, well, forever, basically. All of this is overseen by Fuyuki Nakagawa, general manager in the marine products trading unit for Maruha Nichiro Corporation, one of the world’s largest seafood traders, with more than $8 billion in revenue in 2014 (tagline: Bringing Delicious Delight to the World).

In the next step, the tuna are loaded into a special freezing container built to maintain the fish at -60˚C and shipped off to Japan. (The Japanese abandoned air shipping for more affordable sea transport in the past decade.) Those eighty-three tuna join a conga line of bluefin dancing in cargo holds en route to Tokyo Harbor. If they arrive on a Tuesday, then by 4:00 A.M. Wednesday, they have gone from the harbor to Maruha’s facilities on the outskirts of Tokyo to the Tsukiji tuna auction, the largest in the world. At 4:00 A.M. each day, the country’s major tuna brokers gather around to inspect the catch, somewhere between two hundred and three hundred tuna of varying shapes and sizes shipped in from all corners of the globe: North Carolina, Zanzibar, Morocco, Libya. Tail sections are cut open, allowing for careful analysis of color, aroma, and fat content.

By 5:00 a.m., the morning’s fierce round of tuna bidding draws to a close. The fish move from the auction floor to the buyers’ stalls deeper in the market, where, using a mixture of band saw, katana blade, and fillet knife, the auctioned tuna will be reduced to over a dozen distinct cuts, based on fat content and muscle fibers: from lean pieces of loin to offcuts like collar and cheek. The most prized pieces, chûtoro and otoro, the expensive, fat-flush belly cuts, are reserved for the finest sushi restaurants in Tokyo and beyond—New York, London, even Spain. By the time the tuna make their final voyage from chopsticks to mouth, they will have traveled thousands of miles and passed through a dozen different specialists.

What’s the big deal with bluefin? It’s just fish you say? The boats and the auctions and the prices may all be abstract, but if you’ve eaten a piece of otoro from the hands of a seasoned sushi master in Tokyo or Toronto or Toledo, if you’ve lost your composure over the mix of tender ocean protein and sweet, swaddling fat, you know a bit about what drives this economy. At its most visceral level, Tunanomics is driven by the endorphin-spiking pleasure of a single bite.

That bite has built a $6 billion annual industry that touches almost every part of the globe, and it’s impossible to discuss bluefin without talking about the emptying of the oceans. In scientific and conservationist circles, the sudden surge in interest and the rapid decline in the species population has become the ultimate cautionary tale of what happens when human appetite goes wild. The Japanese have never been known for their restraint when it comes to plumbing the depths of the oceans in search of edible treasures, but the rise of kaitenzushi, conveyor sushi, has transformed tuna from an occasional indulgence into the country’s most important protein.

That bluefin has quickly gone from a pauper to an ocean king responsible for sophisticated economies and multimillion-dollar investments from the world’s largest fishery players underscores just how fragile the world below the water really is. Old-school fishing boats and subsistence fishermen have been subsumed by sophisticated sonar-enabled rigs run by the largest corporations ever to work the water. Careful capturing of the fish during the optimum breeding time has been replaced by a free-for-all fish grab backed by roving airplane spotters—omnipresent eyes in the sky who use their elevated vantage to spot the silver schools from above and relay their coordinates to ready vessels below. Savvy and shadowy maritime corporations have learned to subvert quotas, confounding the world’s management agencies. Against such forces, no animal stands a chance.

More than 1,700 bluefin vessels work the Mediterranean alone. The more they catch, the more prices go down, which means the more these massive boats must catch to meet their annual revenue goals—a vicious cycle with the power to decimate an entire species in a matter of decades. The Atlantic bluefin population has declined 90 percent since Japan Airlines developed its refrigerated shipping system.

Ocean management is tricky stuff—international maritime law, evolving technology, and, increasingly, global warming, all make the subsistence formula a constantly moving target. Perhaps the biggest hurdle for tuna sustainability, and the safeguarding of the oceans in general, starts with the consumer, who remains relatively indifferent to the impact of the fish choices he or she makes. Part of that stems from a basic education gap—a lack of understanding about just how fragile some of our favorite seafood staples really are—but at the most rudimentary level, we’re blind to both the beauty and brutality that is the life and death of a tuna. Bluefin—elegant, sleek, heavy as a bull, swift as a cheetah—is every bit the beast that a lion is, but most of us can better identify a sesame-crusted tuna loin than the fish itself. Human outrage would never erupt over the killing of, say, Tony the Tuna the way it did over Cecil the Lion, shot dead in 2014 in Zimbabwe. Does the fact that we can’t see fish change how we feel about eating them?

The fight to bring the tuna onboard begins.

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

With tuna supplies so volatile and the economy so massive, farming is quickly overtaking the traditional almadraba practice as the preferred method along the Spanish coast. The tuna are still funneled into the nets, but instead of being lifted straight out of the water, they are put into pens and fattened for months before being killed. The taste of wild tuna versus farmed tuna is hard to distinguish, and the farming gives Japanese buyers more control over the age and fat content of the fish. But bluefin require an immense amount of food for fattening—ten times what farmed salmon need by body weight—which in turn means emptying the ocean of tuna’s primary prey: herring, sardines, squid. Anytime we wrest authority from Mother Nature, bad things tend to happen.

Those at the heart of the almadraba are the first to complain about the recklessness of the global fishing industry. For Diego Crespo, fifth-generation tuna baron and president of the Almadrabas de Barbate, overseeing the fishing and distribution of hundreds of tons of bluefin annually, it stings to be roped into the same category as the goliaths of the water. “They’re using airplanes and helicopters and multimillion-dollar tracking systems. We’re using the same nets the Phoenicians used.” Crespo is quick to point out that modern forces threaten both the tuna population and the livelihood of thousands of Spaniards around Cádiz. Bluefin quotas, once above 1,500 tons of tuna a year in these parts, dropped to 500 tons in 2008 and many fishermen, whose families have been catching tuna for centuries, were suddenly out of work. Even those who still had quota left to catch were increasingly coming up empty. “We’d pull up the nets and there would be nothing inside.”

According to Crespo and the other major players behind Cádiz’s tuna economy, the almadraba is the best way forward. Unlike the massive purse seines that haul in a thousand tuna at a time, the almadraba produces very little bycatch, since the holes in the nets are specifically designed to let smaller fish—and young tuna—swim through. And if anyone needs proof of its sustainability, they say, consider its history as three thousand years of proof. There’s a good deal of circular logic in this argument—the tuna will survive because they have always survived—but it’s true that it wasn’t the almadraba that brought the species to the brink of extinction in the early days of the twenty-first century.

Scientists and government agencies have sprung into action in recent years, slashing quotas and imposing strict timetables on when fish can be caught in their life cycle. After Japan scuttled a proposed global export ban on bluefin in 2010, top chefs around the world took unilateral action by banning bluefin from their menus; some fish purveyors still refuse to sell it. Thanks to these concerted efforts, Atlantic bluefin have begun to recover from the historic low hit in 2006 (though Pacific bluefin supplies continue to dwindle). As the fishery community shows signs of cautious optimism, Crespo and his team of fishermen believe it’s time to loosen the quotas and let the fishermen do the work they’ve been doing since the dawn of Hispania.

The Catch

The engines whimper, the rumble replaced by the flapping of fishtails and the grunts of men. The boats surround the catch in the cuadro, a coffin the size of a school bus; now it is man versus fish.

Eight men take the plunge: toreros of the sea set loose to tussle with the thrashing bodies. The panic has left most belly-up, but a few still fight with fins and fishtails to fend off their aggressors. The Moorish meaning of almadraba—a place for fighting—comes into focus.

The mission: wrap a rope around each flapping fishtail, just below the bite of the dorsal fin. But the ample catch and the rising swells turn the cuadro into chaos. Screams and laughter, rage and rapture: the full spectrum of life trapped in a watery grave. “You’re getting old, assholes!” the men shout from above.

A hook and crane lifts the tuna, two by two, from the water. In the piercing sun of midmorning, the colors stick with you: the bright orange slickers, the shimmering silver bodies twisting in the air, the crimson tide below. On board, a knife to the heart brings the ten-thousand-mile journey to an end.

When the water is still and silent, there is nothing left in the cuadro but eight men and a soup of salt and iron. Above, 159 bodies fill the iced belly of the transport boat.

The eight toreros wear the years of battles all over their bodies—dorsal scars, chest cuts, cracked ribs, tail tattoos.

“Protected we are not, son. A beast like this will kill you.”

“I caught a tail to the neck once. Nearly bled out.”

“It’s dangerous, but we have a good time.”

“I heard the Japanese paid a million for one of these a few years back.”

“They should pay us more.”

Pepe Melero doesn’t look like a tuna man. Bald and short with a dense mustache and eyes that dart like goldfish, he looks more like a private detective, the kind of guy used to eating sandwiches in his car and living in the same wrinkled suit for days at a time. But as the head of the restaurant El Campero since 1978—as a chef, a powerful buyer, and one of the foremost bluefin experts in the world—he stands at the intersection of the sophisticated, multilayered tuna economy of southern Spain.

When the ships leave port, Melero knows about it. When the nets come up, he’ll get a call or a text from the boat. If the boys bring in an especially impressive specimen, he’ll be at the docks, waiting to inspect it.

If at first glance Melero seems like a man of few words, it is the tuna that teases out the poet in him. “The noble tuna comes in its natural state, captivated by the Siren song of the Mediterranean, to find peace and tranquility to reproduce in a place where it’s happiest. This is the natural life of the tuna, and it sows its beautiful seed right here in our backyard.”

Barbate is not where you’d expect to find tuna poetry. It feels like the shadow of a town past—the playgrounds are empty, the sidewalks chewed up by time and weather, the stores sell sunglasses and sofas under the specter of liquidation. But on the outskirts you’ll find factories still making salazones and conservas, and on the beaches the same tuna towers used to spot the migrating schools for centuries, and in the center of it all, among an otherwise unremarkable block of apartment buildings, you’ll find Pepe Melero and his shiny white restaurant. If tuna is a religion, then El Campero is the cathedral and Sr. Melero the supreme pontiff.

El Campero wasn’t conceived as a church of tuna. The first iteration of El Campero was started by Melero’s parents back in the 1960s—a casual bar in the center of Barbate where locals would come to drink and snack with friends. Melero was studying to be a pilot in the air force, but he would rise at 3:00 a.m. to be at the bar by the time the fishermen came in for a coffee or a glass of brandy to steel them for the morning ahead. The tuna business was strong back then, but almost everything pulled out of the water went directly to the processing plants on the outskirts of Barbate that would can, cure, and package tuna for distribution around the country. The main tuna staple on the original El Campero menu was Mom’s atún encebollado, chunks of fresh tuna smothered in onions caramelized in pork fat, one of the few fresh tuna dishes with deep history in Spain.

They buck and thrash and use fins like knives to fend off their aggressors.

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

In the end, it was the Japanese who taught the Spaniards how to cook tuna—and, of course, how not to cook it at all. As they took up their exporting posts in Barbate in the early 1990s, the Japanese traders and fishermen would dine at El Campero, but they were distressed to find Barbate’s best restaurant wasn’t taking full advantage of Barbate’s best ingredient. “We let the Japanese into our kitchen,” says Melero, “and slowly they taught us all the different ways they like to eat tuna.”

The only thing the Japanese take more seriously than the trafficking of tuna is the consumption of it. They have hundreds of ways of eating tuna—from broiled collar to stewed offal to fire-blitzed loin. Mottainai, nothing goes to waste, is an underlying Shinto principle with a huge influence on the way Japan eats. More than anything, the Japanese taught Melero and his crew that the tuna is a world of tastes and textures waiting to be explored.

The combination of Japanese guidance and Melero’s persistence—not to mention super-freezer technology that made quality bluefin available year round—prevailed over the years, turning tuna from a one-dish homage to Melero’s mother to the raison d’être for El Campero.

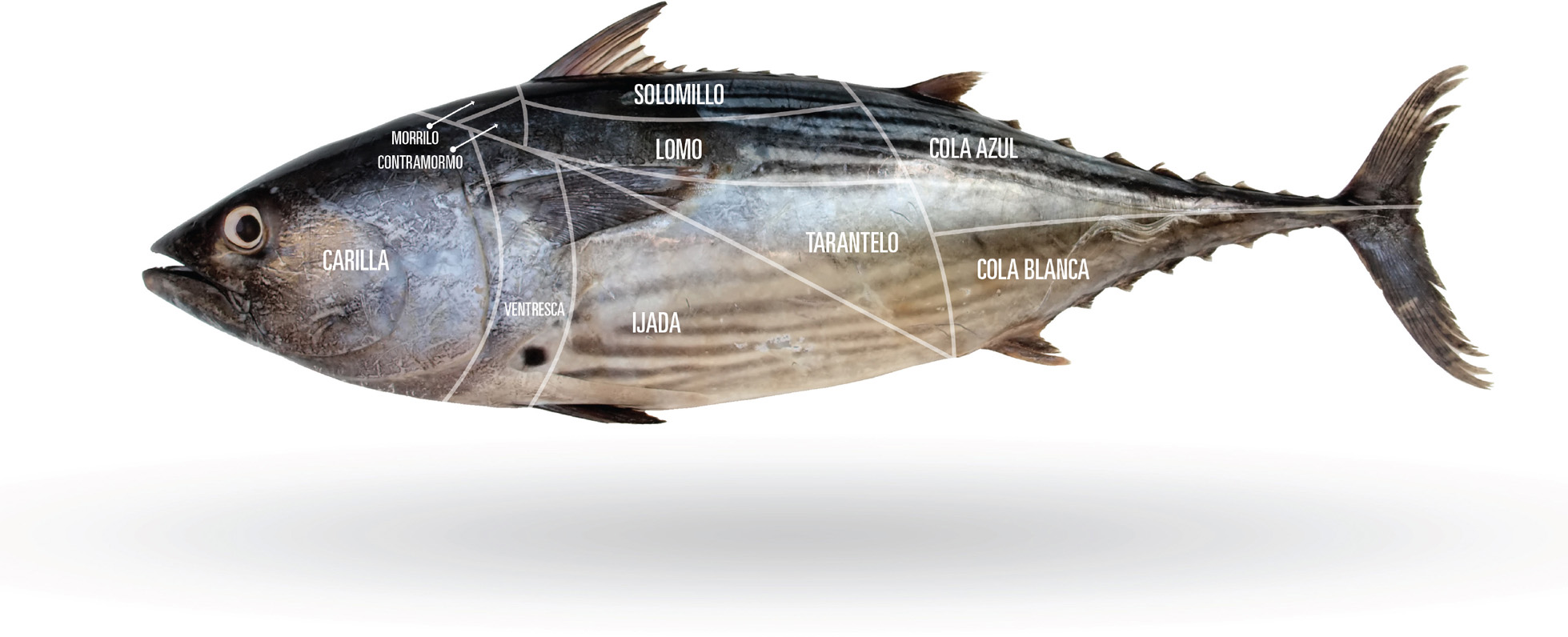

Today at El Campero, mottainai is something of a guiding ethos. You will find a handful of classic preparations along with half a dozen raw dishes that showcase the quality of the product and the reach of Barbate’s tiny but influential Japanese population. But that is just the start of it. Melero and his team divide bluefin into twenty-four distinct pieces, and look at each cut as a different expression of the sea—a unique mixture of muscle, fat, and fibers that demands carefully customized treatment. Tough parts from neck and tail may be subjected to long cooking times; lean parts of the back and center sliced and served raw; and fat-rich specialty cuts may get nothing more than a shower of salt and a quick sear on the plancha, the flattop at the heart of so much Spanish cooking.

Every season brings new challenges and discoveries for the Campero team—new manifestations of the muse to bend to their culinary will. This year’s obsession: el paladar, literally the palate of the tuna, a cut taken from around the lips with a tight texture and deep tuna flavor. They’re also playing with tuna bone marrow, cooking chunks of spine in a thermal circulator, then braising it like rabo de toro, a classic Spanish dish of slow-cooked oxtail. “We haven’t nailed it yet, but we’re getting close.”

I tell Melero I want to taste it all, and he doesn’t disappoint. Lunch starts with a few burgundy slices of mojama, tuna loin salted and cured for three weeks. Mojama is the most famous of the range of tuna charcuterie, a world that includes huevas (pressed tuna roe) and various forms of salted, smoked, and oil-packed meat. It balances the sweetness and funk of the sea with the salt and umami of the curing process, and when made with fatty almadraba tuna like the one Melero serves, the results are extraordinary—the jamón ibérico of the sea.

From there, we move into a series of raw preparations: a rough-cut tartare made from the well-worked muscles of the tail; a ceviche charged with chili and anointed with lime foam; and a plate of dominoes cut from the ventresca, the belly, so densely marbled with fat there’s barely any room left over for protein. In a nod to his Japanese sensei, Melero serves the belly like a plate of otoro sashimi, with nothing more than soy, wasabi, and a few slices of pickled ginger.

Things heat up from there. The paladar, the newest Campero creation, comes atop a bed of lightly mashed potatoes spiked with pork fat and smoked paprika. The meat itself is braised, dark, collapsing—a dead ringer for a beef stew with just the faintest suggestion of the sea. It’s common chefspeak that the creative process starts with the ingredient itself, that the product drives the conversation and the rest falls in line. But that’s not what I see here: at El Campero, Melero imagines a dish he’d like to eat, and then finds the appropriate cut to make it possible.

Next come two plates that transport me a few thousand miles and a few decades back to my days as a meat-and-potatoes poster child: First, tuna “ribs”—thick and substantial bone-in pieces cut from the spine, slow roasted and glazed in a spicy barbecue sauce. The tuna peels off the bone in juicy chunks, the way it used to off my dad’s Weber. The second, perhaps Melero’s most famous creation, the McAlmadraba, is a mini burger made with ground tuna belly spiced with cumin and black pepper and goosed with foie gras and Dijon. All the details are right: the cardboard box, the sesame bun, the drippy special sauce—a Big Mac gone overboard.

The anatomy lesson continues. The deeper I go into the meal, the deeper we travel into the tuna itself.

NECK: Melero’s favorite cut, found just behind the brain, morillo is the apotheosis of all that is great and good about the noble tuna: dense, meaty muscles, rich deposits of fat that swaddle the meat as they warm up. Cooked hard and fast on the plancha with a shower of salt and served with a few sauces on the side that should be studiously ignored.

HEART: Cut in thick planks, marked on the plancha, and served with raw onion and sherry vinegar to rein in the ocean offal.

BLOOD: Cooked and caked and heavily spiced, then stuffed into casing to make maritime morcilla, a convincing riff on Spain’s famous blood sausage.

SKIN: Vacuum-sealed and slow-cooked into gelatinous sheaths meant to recall tripe, Spain’s favorite viscera. To deepen the comparison, they come served in a bowl of braised garbanzos, a riff on callos a la andaluza, the famous tripe stew of the region.

SPERM: The strawberry seed of the migrating tuna, skewered into a lollipop and dressed with onion jam and ginger-peach compote to hammer home the sweetness.

He talks about the Japanese-style creations with reverence and appreciation, but in the end it’s the Spanish-inspired inventions, the voyage into uncharted territory, that moves Melero most. After thirty-eight years of exploration, he has hundreds of recipes in his memory bank, and a few dozen more waiting to be filed. Still, when it comes time to eat, Melero takes his tuna two ways: griddled or smothered in onions, just like Mom used to make it. “I don’t care for raw tuna. I just don’t come from that culture.”

The Breakdown

Giant claws bring the bodies, two at a time, from the bowels of the boat to the floor of the fábrica de despiece, the butchering room of the Barbate tuna factory.

Thirty men with hooks and blades break the bodies into pieces. Chain saws for the head, swords for the loins, kitchen knives for carving out the imperfections. Heads and tails in one bin, organs in another. These were gold once, pressed into service to season an empire. Now they await a less delicious fate.

Beyond the blood, bones, and brawn, the day’s prize: four quarters of flesh, long purple planks placed on metal trays stacked ten feet high.

In the sea of Andalusians, three Japanese: two quartering fish, another talking to Tokyo. All of them look anxious.

The room sings with cracking bones and grinding gears, a disassembly line of fantastic efficiency. With every minute the tuna loses what the world values most. Forklifts push thousands of pounds into powerful blast machines. Super freeze they call it, from cool to cryogenic in fourteen hours, the ideal state for the long road ahead.

The largest tuna weigh up to 1,200 pounds, roughly the size of a bull.

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

But not all tuna will travel. Some have a home in Barbate, others farther north with chefs who know just what to do with it.

The butchers wash the blood from their hands, trade rubber for denim, and step into the daylight. Some set off to Ca Reventa to settle bets and share stories. Others go straight to lunch: steak or stew or maybe another sandwich. Almost no one eats tuna.

Mr. Nakagawa of Maruha Nichiro Corporation doesn’t bother changing. “It was a good day,” he says in between drags in the parking lot. “Too good, maybe. Too many fish in the cuadro. Fear can compromise the meat.”

In six months, at a hinoki countertop in Ginza, no one will taste the fear.

If Barbate is the town that tuna built, Zahara de los Atunes is the town that tuna is building—a thicket of restaurants, bars, and souvenir shops with the coastal mascot at the center of it all. Stores sell novelty cans of tuna with fish heads peaking out; signs and shirts show smiling bluefin drinking beers and singing songs; restaurants bear the name of the most famous citizen—Thunnus, Hotel Almadraba, Cervecería El Atún. Everywhere you turn, menus run long on seared fillets, sashimi, onion-slathered loins.

The centerpiece of this burgeoning tuna economy is the annual Ruta del Atún, a coordinated effort by the local government to turn the fatty flesh of the almadraba into an enduring PR machine for the hospitality industry. Forty odd restaurants participate in the five-day event in May, each offering a single taste of tuna. Up and down the coast, Barbate, Tarifa, and Conil de la Frontera, towns with their own almadrabas, also have their own Rutas. When it first started in 2010 in Zahara, the offerings were what you might expect from a southern Spanish town easing its way into a tuna culture—seared belly, tartare with Japanese whispers. But the ambitions of the event have grown substantially in five years. Now, it’s not just tuna tapas, but tuna butchery demos, tuna conferences and panels, tuna sculptures, tuna poetry, tuna documentary screenings.

At 1:00 p.m. on a Thursday in May the coastal town is electric with the hunger of prowling tunaheads. Part of it, no doubt, stems from the fact that every tuna creation comes with a beer or wine chaser, but everyone, from the servers to the line cooks to the mix of Spaniards and foreigners, seem genuinely caught up in the revelry. Diners carry elaborate maps with glossy color photos of every dish and passports (“tunaportes” one server jokes) for stamping at every stop they make.

I get my first passport stamp at Thunnus, a small fusion spot off the main drag: fillets of tuna marinated in sesame, soy, and sake, wrapped in thin sheaths of shaved shiitake and sauced with thickened dashi. Japan makes for a fitting start to today’s journey.

Vaguely Japanese touches—wakame, wasabi, sesame—show up everywhere, but many restaurants have abandoned the safe shores of the Far East and sailed into deeper waters. Hotel Antonio, a longtime tuna haunt and winner of the best tapa in two of the first four events, calls 2015’s dish Red Hot Tuna Peppers: a squid body stained red with beet juice and chili and stuffed with raw tuna. At Taramanta the tuna comes in a tube of toothpaste to be squeezed over a cracker studded with sunflower seeds. La Tasca calls its creation Canta Atún, a mini record player with a tipsy fish on the record and a microphone to the side. The vinyl is real, but the microphone is fashioned from phyllo dough, stuffed with tartare, and covered with dark sesame seeds to complete the effect.

Taking a cue from El Campero, the restaurants of Zahara have turned the local catch into both canvas and paint: stuffed into tacos, ground into meatballs, suspended in fondue, sandwiched with swipes of dark chocolate. The question isn’t whether these dishes are delicious or not (many of them are); what matters is that they exist, and that people are here, filling out the streets of this tiny coastal town on a Thursday afternoon, brushing their teeth with tuna toothpaste and biting down on marine microphones.

The fact that a single ingredient can essentially elevate the creative and technical prowess of an entire town’s restaurant industry is a testament to the excellence of the tuna itself—something that can be seared, stewed, cured, ceviched, carpaccio-ed, tacoed, pattied, planked, liquefied, emulsified, and stuffed into everything from plastic tubes to cephalopods. But it also testifies to a coastline of industrious souls, Spain’s first civilization, who have shown it’s never too late to adapt. When the week is out, Zahara and its visitors will have consumed ninety-nine thousand tuna tapas, many of which will move on to become staples of the local restaurant scene.

The last stamp in my passport comes from La Malvaloca. They serve a small bowl of cocido, the most traditional dish in all of Spain, fashioned entirely from tuna. The traditional chunk of chorizo is made with tuna tartare stained bright red with the same flavors of the pork version: smoked paprika and roasted red pepper. The morcilla is fashioned from ground tuna heart and tuna blood. A few toothsome garbanzo beans and a puddle of clear tuna broth tie the dish together.

The flavors are as powerful as they are perplexing: it tastes both entirely of cocido and of the sea, a magical bridge between land and water, past and present. It’s not the taste of Japan, not the flavor of fusion or fashion or a passing interest. It is the taste of a culture, still in its infancy, three millennia in the making.

Best Cuts

ATÚN ROJO

TUNA TACTICS

For many years, Spain’s tuna culture was based largely on dried and canned products. But bluefin’s star turn in the Spanish kitchen has created a culture of specialization, where every cut has a different taste and texture to be teased out by fire and finesse.

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

GONZALO SÁNCHEZ

Fisherman, Cádiz

![]()

“Every year it seems to get a bit harder. Less fish, less money. But I’ll still be here. I can’t get enough of the sea.”

Matt Goulding

SISTER CONSOLACIÓN

Nun and Baker, Medina-Sidonia

![]()

“Spanish nuns have always made sweets. Eating sweets isn’t a sin, but you need to eat them after a meal.”

PATRI MANES

Flamenco dancer, Madrid

![]()

“Flamenco is an expression of the soul. It gives voice and movement to your deepest feelings. When I don’t dance, a part of me dies.”

SALEM KHABBAZ

Shawarma master, Barcelona

![]()

“Making good shawarma is like making poetry. You say as much as possible with as little as possible.”

Matt Goulding

KINGDOM OF COLD SOUPS

No country on earth can top Spain’s cold soup game. The desert climes of Andalusia birthed a trinity of sopas frías: gazpacho: ajoblanco, a dreamy puree of garlic and almond: and salmorejo, hailing from Córdoba but found in bars across the region.

FROM SCRAPS TO SOUP

Cold soups accomplished two objectives: providing cooling nourishment for shepherds and manual laborers working under the sun, and utilizing cheap, abundant ingredients (old bread, garlic, olive oil, tomato) to fill bellies in one of Spain’s poorest regions.

SUPER SUAVE

Like most of Spain’s best dishes, salmorejo’s ingredient list is short. The beauty lies in the velvety smooth texture created by blending ripe tomatoes, stale bread, garlic, sherry vinegar, plus enough extra virgin olive oil to achieve a brilliant orange color.

DRESSED TO IMPRESS

The fun stuff goes on top, not inside, a salmorejo. Chopped boiled eggs, chunks of jamón, and a final swirl of olive oil complete a complex picture: salty, savory, sweet, and sharp—a world of tastes in a clay terrine of cold soup.