![]()

When I travel to a city, I come with two simple objectives: to walk a lot and to eat a lot, goals with a certain symbiotic kinship. I’ve dedicated many days to doing both in Madrid: as a cerveza-soaked teenager first on the loose in Spain, as a young journalist eating elaborate feasts of fish and fowl on someone else’s dime, as a new husband looking for nothing more than a weekend of memories with my Spanish bride. The longer I spend in the capital, the more I come to realize: Madrid isn’t a place you want to take sitting down.

Hemingway had it wrong: He spent most of his time here holed up in Sobrino de Botín, where Jake and Brett sought refuge in the final pages of the The Sun Also Rises, bathing himself and his loyalists in wine and nostalgia for hours at a time, saving the peripatetic pleasures for the cafés of Paris. Now more than ever, Madrid is a movable feast.

And Madrid looks pretty damn good when it moves; it would give Milan a run for its money as the world’s best-dressed city. Walk the streets midday and find yourself in a sea of soft fabrics and custom-cut suits that conform to Spanish bodies in ways they will never conform to yours or mine—an animate expression of the word you most often hear other Spaniards use to describe Madrid: señorial. Stately, like those wide avenues and smooth stone columns; regal, like the gold trim and the horse-and-chariot fountains. Those Italian loafers look good beneath the red and gold of the Spanish flag; that confident step, the one that leads with the chest, marches perfectly to the rhythm of the capital’s traffic.

Don’t be fooled by the good looks and svelte figures—these suits eat more, drink better, and stay out later than the rest of Spain. You’d be wise to follow them. If you do, you’re likely to end up in Ibiza, in a few-block section just to the northwest of Retiro Park known for the density of its quality, polished restaurants and tapas bars.

One o’clock is the hora de aperitivo, the warm-up ritual observed by the better part of Madrid’s workforce—a bridge between the grind of the morning and the slow pleasures of lunch ahead. Any good wolf pack of suits will start with a caña—say at Arzábal, where a well-poured beer (does anybody in Spain know how to pour a beer better than a madrileño?) and a plate of anchovies from Cantabria make for a bracing transition to the more serious eating that lies ahead.

Laredo is where the well-heeled form like Voltron Vutton—a loud, lively mass united by their dedication to good food and navy blue. Men with ties slung over their shoulders excavate the protein from mountains of shellfish; groups of stunning women—who may or may not be returning to work, depending on whether Rosio orders a glass or a bottle—nibble on the ribs of rabbits, fried and dipped into puddles of aioli.

I survey the room and have what everyone else is having. The salmorejo, the satiny orange union of blended tomato and fruity olive oil, thickened with bread and garlic, further proves that Spain is the king of cold soups. A loose scramble of blood sausage and baby fava beans—sweet and funky with a gentle undertow of iron. And the star of the bar: fried shrimp and asparagus bound in a cloak of Japanese mayonnaise, a plate nestled on every table I see (two next to Rosio and her crew, now on their second bottle of Albariño).

A few blocks down on Calle Ibiza, you’ll find one of the newer kids on the block, Taberna Pedraza, owned by Santiago and Josefina Pedraza—husband works the floor while wife holds down the kitchen. If Madrid is a quilt of regional Spanish food culture, Taberna Pedraza is where it all comes together.

The couple both lost their jobs during Spain’s economic downturn and decided to bend the crisis into an opportunity. They spent a year traveling around the country, eating their way deeper into the DNA of Spain’s regional cuisine. They ate fabadas and cava-aged cheeses in Asturias, fried fish and stuffed mussels in Cádiz, migas and acorn ham in Extremadura. Taberna Pedraza presents the diner with the greatest hits of their travels—not just the recipes, but the ingredients they found along the way: the thin, lightly spiced chistorra of Lasarte, the poetic olive oil of Casas de Hualdo, the finest I’ve tasted.

The croquetas have earned a dedicated following around town (they won best in the city at Madrid Fusion in 2014): a shattering crust just barely contains a lava flow of béchamel that tastes like a jamón milkshake. Some say the tortilla is even more of a category killer, made with eggs from pampered hens and thinly sliced Galician potatoes that Josefina fries to order in individual batches. As if she was making a good French omelet, she works the eggs over a low flame, and it arrives to the table soft and pale, jiggling like a waterbed; slice into it and it exhales across the plate. (So popular is the tortilla that a ticker counts off the number ordered since the restaurant’s inception; mine, number 11,421, is a fine specimen, if not a little shy with the salt.)

“The more history you have, the less liberty you have to play,” Santiago tells me. “We have better products, better techniques. If we can improve a classic recipe in a meaningful way, why wouldn’t we?”

Move down the menu and move across the peninsula: boiled artichokes peeled open like blossoming flowers and drizzled with olive oil, tigres, mussels stuffed with sofrito and a prick of spicy smoked paprika, funky aged beef from Galicia kissed on the plancha and served black and blue. And back to Madrid with a plate of callos, the offal obsession of the capital. Finish in Cantabria with quesada pasiega, the precocious love child of flan and cheesecake, a wish that all Spanish meals ended along the northern coast.

Santiago Pedraza, slicing tortilla number 11,421.

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

Everywhere you eat and drink in this part of town will leave you wondering if the guy on the stool next to you shoots elephants with the king. Another day takes me to Ave, a restaurant dedicated to creatures of flight. The food is fine, but the clientele is better. I run into the cabinet of the Real Academia de Gastronomía, a distinguished body of men and women whose official charge is to “positively influence the gastronomic offer of Spain and improve the quality of life of Spaniards.” The median age of today’s crew hovers somewhere north of the Warren Buffett neighborhood. Some wear suits with the group’s emblem emblazoned on the right breast.

We exchange business cards like a Japanese boardroom, stopping to admire each other’s rank and purpose. The oldest in the group, Pedro Aznar, presses a card into my palm with a number scribbled on the back.

“Here you go, young man. That’s my personal number. Anytime you’re near Logroño, you’re welcome to stay and drink with me.” Later, I discover he owns Marqués de Riscal, one of Spain’s largest wineries, and the accompanying hotel, designed by Frank Gehry. I put the card in a safe place.

Say what you want about the affectations of a governing body of gastronomy, these guys know how to eat better than you and me combined. They leave me with a list of first-rate bars and restaurants that I work my way through over the coming days, until I’m ready to pledge my allegiance to this august gathering of gastrocrats.

My favorite place on the list is Asturianos, an unsuspecting restaurant in Vallehermoso serving superlative versions of Asturias’s soul-soothing cuisine: plump sardines swimming in an emerald stream of olive oil, golden nuggets of potatoes bathed in a sharp Cabrales cheese sauce, fabada, the iconic pork and white bean stew, that would make an Asturian coal miner weep.

I eat here with Victor de la Serna, an old-school scribe with a big appetite, strong opinions, and a crop of loyal readers who feed off of both. He forms part of a tradition of writers—critics, essayists, reporters, novelists—who have played an outsize role in shaping the culinary landscape of Spain. With biting critiques and challenging think pieces and stirring love letters, guys like Néstor Luján, Josep Pla, and Manuel Vázquez Montalbán—and Victor—imbued cuisine with an academic and cultural gravity, laying the foundation for generations of thoughtful cooks and eaters.

Born in Cantabria, Victor has been writing about food and wine in the capital for the past fifty years. “Madrid, more than anything, is a collection of regions. This is the city that migration built, one that attracted the Galicians and Andalusians and Asturians.” What do immigrants do when they come to a new land? They open restaurants.

As I drop the last sardine in my mouth like a cartoon cat, the chef, doña Julia Bombín, comes out of the kitchen to ask how much more we’re prepared to eat. We tell her that we have a long night of eating in front of us, but she won’t let us leave before tasting her arroz con leche—tender rice cloaked in Asturian cream and crowned with cinnamon and caramelized sugar, so staggeringly delicious I am tempted to cancel my other eating plans and pitch a tent in the dining room.

As we knife through the backstreets of Malasaña and Chueca on our way to the next destination, Victor finds something to celebrate on every block. “They have the best pescaito you can imagine here. Better than the fry joints in Cádiz. . . . I wish we had time to try this Galician restaurant. Incredible seafood. . . . My sources tell me this new Murcian place is doing fine work.”

In the hands of a guy like Victor, you get the sense that the feast in Madrid knows no bounds. You could happily spend a lifetime eating your way around Spain without ever leaving the capital, Victor insists, and in many cases, doing so better here than you would on native terrain. But I am not after the flavors of Spain at large; I want the pure taste of Madrid, and Victor knows where to find it. Tomorrow, we will not eat marmitako from Bilbao or migas from Cáceres or arroz negro from Alicante, but the one dish that represents Madrid and its cuisine better than any other.

![]()

“Spain is the strongest country in the world. Century after century trying to destroy herself and still no success.” Keep in mind that Otto von Bismarck, the engineer of a unified Germany, said this in the late nineteenth century, more than fifty years before the Spanish Civil War and the decades of internal turmoil and national soul-searching that followed.

Even in the nineteenth century, though, Spain had more than 1,500 years of internal strife behind it. The Visigoths versus the Moors. Catholics versus Moors. Catholics versus Jews. Catholics versus everyone, including themselves. The Reconquista, the Inquisition, the Civil War: in some form or another, all involved one group of Spaniards violently questioning the legitimacy of another.

The subtext behind the constant infighting, political maneuvering, and at times naked violence employed by the various factions vying for supremacy was the same question Italy, France, Greece, and others across the Mediterranean were struggling to answer: What makes a country? A political decree and a national army? Shared language and culture? A collection of lines on a map?

In 1469, Isabella of Castile married Ferdinand of Aragon, thus uniting the two largest and most contentious factions of Christians on the Iberian Peninsula. Together, in 1492, they drove the Moors from Granada, ending 781 years of Islamic rule and uniting Spain as one country for the first time. The Catholic monarchs went on the march, undertaking two hundred years of empire-building at a breadth and scope the world had never seen. Columbus cracked open the New World for the Spanish crown, and two men from a dusty corner of Extremadura in western Spain gathered their horses and their men and crossed the Atlantic in search of gold and glory.

What followed were two of the most impossible stories of empire expansion in human history. Hernán Cortés, with a crew of 500 men and a plague of European diseases riding shotgun, toppled the Aztec empire, one of the largest and most sophisticated civilizations of its age. Inspired by his distant cousin’s success, Francisco Pizarro set sail to Peru in 1531 with 180 men and 27 horses and, over the next few years, brought the two-million-strong Incan empire to its knees. With the spoils of the New World, the Spanish crown had the resources needed to expand its empire across Europe and into Africa and Asia. Three hundred years before British rule reached its peak, the sun never set on the Spanish empire.

The Siglo de Oro, Spain’s golden age, wasn’t just about territorial expansion, but a flourishing of art, literature, music, and architecture that would dramatically reshape intellectual thought around Europe and beyond. These were the years Cervantes and Lope de Vega transformed literature and drama, when Velázquez and El Greco developed a new language on the canvas. But for all the remarkable political and intellectual achievements of the Siglo de Oro, it failed to create a coherent vision for a unified country.

Over the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Spain lost its territories to revolts, piracy, military defeats, and fractured internal politics. By the time King Amadeus of the House of Savoy was tasked with uniting the country in 1870, he proclaimed the people of Spain ungovernable and beat a trail across the Mediterranean to Italy.

Today, a not-insignificant part of Spain would rather not be a part of Spain at all. The Basque separatist campaign dates back to the late nineteenth century, fomented in the wake of the Carlist Wars. By the 1950s, the most extreme faction of nationalists began to wage war on central Spain, a campaign that resulted in a red tide of car bombings, kidnappings, and political assassinations. ETA’s reign of terror subsided at the dawn of the twenty-first century, even if the Basque dream of secession has not.

Catalunya has been trying to escape this country since 1714, the year it became part of it. Catalans have always viewed themselves as an independent body, with their own language, culture, and national identity. In recent years, with the residue of Franco finally dissipating and the collapse of Spain’s economy exposing a new set of regional grievances, that belief has taken on a new momentum. The forceful Catalan campaign, based not on violence, but on popular uprising and savvy political maneuvering, has positioned the region a few steps from independence. (At this rate, I could be living in a separate country by the time you read this book.)

But it’s not just the two most visible separatists that dream of independence. In Galicia, the gallegos still have their own language, their own cuisine, their own temperament. You’ll find pockets of radical independent factions scattered throughout Asturias, as I did one morning at 2:00 a.m. in Avilés, when a local friend pinned an Asturian flag to my jacket before we walked into a bar: “Trust me, we need these to drink here.” Even Andalusia—home to so many of the toasted brown stereotypes of Spanish culture—has its strains of nationalism; southern factions have been trying to separate from Spain on and off since the Duke of Medina Sidonia attempted secession in 1641.

So what holds this nation of nations together? King and constitution? Catholicism and castellano? Perhaps, but they do little to explain what it means to be a Spaniard—to live and eat and drink like a Spaniard. More than anything, it might be food that connects the disparate peoples of this country in some meaningful way: a common pantry, a shared palate, a handful of emblematic dishes that surface in bars, restaurants, and markets across the country. Tortilla, gazpacho, paella—these may be the country’s most famous culinary creations, but if one dish represents a centralized Spain, a Spain connected by history, culture, and circumstance, it is cocido.

Cocido started off as a Jewish dish dating back to the Middle Ages, known then as olla podrida—a collection of meat, beans, and vegetables gathered in a clay pot on Friday nights and left to simmer in the embers of the fire for eating on the Sabbath. When Catholics reclaimed the country, pork went into the pot, an edible litmus of sorts to test your allegiance to the Holy Roman Emperor. If your stew didn’t have swine, then you must have been a Jew or a Muslim in disguise.

Like the other great peasant stews of Europe—pot-au-feu from southern France, bollito misto from central Italy—cocido is a simmering pot of necessity, crisis turned into opportunity through patience and ingenuity. What Néstor Luján called “the peak of the cuisine of evaporation.” None less than Sancho Panza, one of the world’s great fictional gastronomes, was an avowed enthusiast: “This great steaming plate that I believe to be olla podrida, because of the diversity of things it contains, I won’t stop bumping into ones that I like.”

Cocido madrileño, with its garbanzo base and mixture of pork, chicken, and beef, is the mother of all cocidos, but every region of Spain has its version. In Murcia, the garden of Spain, cocido comes filled with plant matter. Asturians replace garbanzos with fat white beans in their smoky, pork-heavy fabadas. In Catalunya, escudella i carn d’olla unites meat and vegetables and a giant pilota, a meatball made from ground pork, breadcrumbs, and egg. The puchero valenciano, bullit mallorquín, berza gitana, cocido montañés—the list goes on and on. “If there’s a meeting place for Spanish cuisine, it’s cocido,” Victor de la Serna tells me.

Many madrileños insist that cocido needs to be eaten at home—like our family friend Rosa, who has been making the same fantastic version for forty years, and who carries gallons of Madrid water to make cocido whenever she travels. But you’ll find restaurants across Madrid serving up perfectly solid versions of the staple, especially on Wednesdays, cocido day in the capital.

For the best cocido, though, you’ll need to travel outside the city, to El Escorial, the great granite monastery and royal retreat erected by Philip II in the seventeenth century, tucked into the foot of the Sierra de Guadarrama. There, a few blocks from the magnificent stone structure, you’ll find Charolés, opened in 1977 by the Minguez family.

Cocido comes in three stages, called vuelcos, a staggered meal meant to stretch the bounty of boiled meat and vegetables and the very limits of human digestion across a few hours of exaggerated feasting. Things begin innocently enough; the first pass, like a good bouillabaisse, is simply a bowl of the caldo, the rich, complex cooking liquid, usually with a drift of short noodles floating on the surface. In the second vuelco comes the ostensible star, the garbanzos, cut from the mesh sack they’re simmered in and drizzled with olive oil. Unless you live in the Middle East, and even if you do, these are likely to be the best garbanzos you’ll ever eat. And finally, the third vuelco: the meat from the simmering cauldron.

That’s the basic blueprint, but Charolés takes the whole production to ludicrous extremes: stewing hen from Santa María; plates of bone marrow with tiny spoons for excavating the semi-solid innards; two types of tocino, back fat so rich and luscious it eats like goose liver; pink chunks of salted ham; snappy red coils of smoky chorizo; muted brown beef ribs meant to be played like harmonicas.

Along with the protein procession comes a tour of the garden: boiled Galician potatoes dressed with olive oil, stewed cabbage lashed with smoked paprika, spinach and chard studded with chunks of jamón, whole simmered carrots that owner Manuel Minguez assures us have been out of the ground for less than forty-eight hours. By the time the tuxedoed servers nestle the last plate onto our enormous table, there is not a square of visible tablecloth remaining.

Minguez, justifiably proud of his restaurant’s Herculean creation, comes out frequently to offer us new parts of beasts plumbed from the depths of the pot. He straightens his suit and tie, rubs his hands like a traveling salesman, asks if we might like to hear a story—about the provenance of the pork, the secret to the garbanzos, the history of the bowl itself.

“I come from a humble family and we ate cocido every day growing up—not this cocido you’re eating, but one with a few garbanzos, a bit of chorizo, maybe a piece of hen.” You’ll hear that same sentiment echoed from the older generation across Spain—cocido being less of a recipe and more a manner of making the most of what you had on hand. Once upon a time, when Spain was starving, owls, eagles, and rats found their way into cocido.

“It used to be a serious plate, an important plate, the kind of meal you ate once or twice a week,” says Victor, wistfully. “Now with the modern diets, it’s no longer the same. It’s a niche plate. Maybe eight or ten good places in Madrid still serve it.”

Chief among restaurants still dedicated to cocido is Lhardy, located a few steps from the Plaza del Sol.

Ask a madrileño where to eat a good cocido in the city and odds are they’ll say Lhardy. By some accounts, Lhardy was Spain’s first fine dining restaurant, in operation since 1847. Milagros Novo, the great-granddaughter of Emilio Lhardy, the restaurant’s founder, makes a lovely hostess. Before lunch, she shows me the rooms where heads of state dine, the favorite tables of kings and kingmakers. The wooden floors groan with history. “This was the only place the queen could eat—either the palace or Lhardy’s. Since then, it’s been a meeting place for the most important artists and politicians of Madrid.”

Beyond cocido, people come here to eat Madrid’s other most iconic dish: callos, tripe simmered into submission with aromatics and chunks of chorizo and blood sausage, a potent bowl of texture and substance that dates back to the late sixteenth century. Both cocido and callos have been humble cuisine for most of their history—of cuts sold cheap and worked long and slow until they give up the ghost and take on some other incarnation. The story has it that the founder’s son used to bring his Bohemian friends to eat at Lhardy’s, and they introduced callos and cocido as soul food for the free thinkers of old Madrid. “The bohemians are always hungry,” says Milagros.

Something of the soul-warming essence is lost in the pageantry. Men in suits are fed by men in suits who serve soup from silver chaffing dishes. It feels like eating lunch in the Prado. The cocido is a perfectly fine specimen: the quality of the individual components—from the lighter broth to the less-precisely cooked proteins—can’t compare with Charolés, but it gets the message across forcefully enough. Surrounded by suits and suit pants, it’s impossible to imagine that anybody eating here has afternoon ambitions. After a bowl of tripe, a three-course cocido, and Lhardy’s take on a baked Alaska, I barely have the strength to make it back to bed.

Tuxedoed cocido service at Lhardy, Spain’s oldest fine-dining restaurant.

Matt Goulding

Lhardy doesn’t fit in the way it once did. It feels like a character from a Goya painting wandered off the canvas and is looking for his place in a city he no longer recognizes. “My son told me we should go for something a little more minimalist,” says Milagros. “I just about died.”

This is old Madrid, la España castiza, ripe with history and majesty—the culinary equivalent of Neptune fountains and royal portraits—and long may it live.

![]()

Sacha Hormaechea is short and spacious, with a wide nose and salt-and-pepper hair that long ago migrated from his head to his cheeks and chin. He speaks with a soft but commanding voice, filled with delicate details and tantalizing turns of phrase—the poet laureate of the Madrid kitchen.

In a way, Sacha’s story is the story of Madrid: His father, Carlos Hormaechea, was Basque, his wife, Pitila, Galician. They opened a restaurant in the northern part of the city, just beyond the Bernabéu soccer stadium, in 1972, and named it after their son. Over the years, Sacha developed a reputation for serving simple but sophisticated fair to a mix of politicians, thinkers, writers, and artists.

If Lhardy is old Madrid, Sacha is middle-aged Madrid—mature, self-assured, equal parts classic and contemporary.

Sacha took over the restaurant in 1996 and has created a rare species of supper club, with old paintings on the walls and flickering candles at the tables. Madrid’s elite feel at home here, as do off-duty chefs—precisely because Sacha cooks the kind of food he himself loves to eat. When I ate here years ago with a crew of international chefs, Morgan Freeman and a Spanish film director sat across from us, chewing on steaks. We ate a wild mushroom tortilla that seemed to melt onto the plate, a pile of briny-sweet sea urchins, and a microwaved potato that years later I still talk about every few weeks.

I catch Sacha outside before service on a warm spring day and he offers me a fishbowl gin tonic. His reservoir of knowledge for Madrid is deep and his mind is restless, so conversations turn into slow-migrating monologues, as if he were playing a game of telephone with himself.

“Madrid is an island of lambs. It’s totally absurd. You have a city built on a mesa with nothing but lamb grazing around, and inside you have the second largest fish market in the world. We auction off a greater variety of seafood than anyone else in the world. You won’t find a barrio in Madrid without shrimp, without barnacles.”

Catalans and Basques have a reputation for regional chauvinism, but madrileños know a thing or two about pride too. “The most important thing to know is that besides San Sebastián, Madrid is the best place to eat in all of Spain—thanks to the migrants, who have brought all of the best of Spanish food together in one place.”

In Sacha you will find a flood of fascinating table talk—that the original sauce for patatas bravas, Spain’s most famous fried potatoes, comes from the leftover cooking liquid from cocido, that there were no kitchens in the Alhambra, that the concept of clandestine restaurants was born in Madrid during the time of Cervantes. Occasionally, the man goes overboard, like when he calls the pepita de ternera, the madrileño steak sandwich, the greatest sandwich in the world. But all the great ones go overboard, because that is how they show the world how much they care.

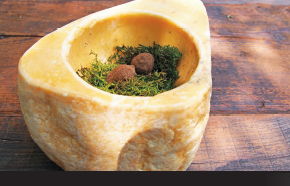

At the table, though, there is no questioning Sacha’s taste. First, a single lightly cooked red shrimp, head separated from the body and placed beside a granite mortar filled with roasted garlic, grassy olive oil, and a battery of leafy herbs. Sacha instructs us to squeeze the shrimp head, extracting its brains into the mortar, then use the tail meat to stir it all together and eat. Genius.

Next, a spring gazpacho made from wild asparagus, radish, and dill, a complex convergence of bittersweet notes and soft and snappy textures—a bracing reminder that gazpacho is an idea, not a recipe. Sea cucumber can be an expensive mistake in most hands, but Sacha’s team teases from it a supple elegance that makes you question if you’ve ever truly tasted it before. For dessert, a jiggling cylinder of tocino del cielo, basically a pork flan, a totem of Spain to slide your spoon into.

There’s a strange comfort in the restaurant’s confidence: The server might not have a clue what went into the dish, but he’ll stir you the coldest fucking martini of your life, the kind where a thin shelf of ice forms on the surface. I’m told by some that not everyone is treated the same here, that important madrileños are the ones being feted with table-side truffles and regaled with stories of the city’s underbelly. If Madrid had a mafia, they might find a fitting home in a low-lit corner of Sacha, working over a femur of bone marrow.

After dinner, we sit around drinking mezcal with a group of young actors and academics—the kind of scene Vargas Llosa might paint with his pen. There is no shortage of intellect or opinion among them, but we are in Sacha’s house; he pours the liquor, he sets the table. As the agave takes gentle hold, he returns to Spain’s Siglo de Oro.

“What we’ve never done well is we’ve never explained to the world that it all began here: Pizarro brought the first tomato plant to the port of Vigo. Ceviche wouldn’t exist without lemon. Fish and chips don’t exist if we don’t bring back the potato. After Spain, you didn’t need to go out looking for spices. We were the ones who changed the history of the world.”

![]()

If much of Madrid seems content to celebrate the glories of the past, others occupy themselves with the triumphs of the future. David Muñoz is the apostle of New Madrid, sent down from the heavens to give the finger to conformity and rescue Madrid from the long shadow cast by the more famous kitchens to the north.

Dubbed an enfant terrible by the Spanish press, his Mohawk, his model wife, and his fuck-’em-all attitude form a vital component of his personal brand. He has a penchant for picking fights with culinary heavyweights both here and abroad. In this way, Muñoz has positioned himself as the wunderkind outsider in a world too rigid to understand his brand of radicalism.

Muñoz comes from humble roots. Born in 1980 in a working-class barrio of Madrid, he took to the kitchen at a young age; some of his earliest culinary adventures include baking squid and seaweed cakes in the microwave. After years cooking high-end Asian food in London, he returned to Madrid to open DiverXO in 2007, and quickly gained a following for his brash style and discordant combinations. By 2010, it had its first Michelin star; two years later came the second. When Michelin anointed DiverXO as Spain’s newest three-star restaurant in 2013, the country went nuts. Yes, there were already seven gods and goddesses atop Mount Michelin, but all but one resided in Catalunya and the Basque Country. The Basques had the Arzaks and Andoni, the Catalans had the Adriàs and the Rocas. In Muñoz, Madrid finally had its homegrown hero. (A hero with a powerful sidekick; in 2015 he married Cristina Pedroche, a television personality whose fame in households across Spain dwarfs her husband’s.)

With all of this in mind, I sat down to dinner at DiverXO with trembling anticipation—ready to taste the latest iteration of the Spanish revolution. The restaurant announces its ambitions to disrupt at the doorway: spinning circles of psychedelia, black butterflies fluttering on the wall, and everywhere, the famous flying pigs that Muñoz has chosen as his spirit animal. Servers wear monochrome jumpsuits, a cross between a posse of break-dancers and a chocolate factory of Oompa Loompas.

On the plate, Muñoz deploys flavors that haven’t commonly been harnessed at the upper echelons of Spanish fine dining: miso, chilies, hoisin, XO sauce. On the fork, he concentrates energy like a black hole: a corn and lychee soup that will make you question whether you’ve ever tasted either before, duck hearts wearing a cloak of warm Indian spices that override your brainwaves like a hallucinogen, or a play on pad thai that will make you forget the millions of mediocre Asian fusion dishes clogging up the world’s fancy restaurants. The so-called show reads stronger as an aesthetic and an attitude than as groundbreaking cooking, but it’s still outrageously delicious.

David Muñoz’s food concentrates energy like a black hole. Here, StreetXO’s club sandwich.

Matt Goulding

DiverXO remains the most difficult reservation in Spain, but Muñoz has taken his brand of audacious dining to the top floor of an El Corte Inglés department store. This is an area more in need of a shake-up in Spain: the midlevel restaurant. Not just modern tapas bars, which grow on olive trees in these parts, but casual, outward-looking, well-priced restaurants that take their food more seriously than they take themselves. And that’s exactly what StreetXO is: loud, arresting, the kitchen a kinetic mass of cooks grilling proteins, wok-frying noodles and plating dishes with a street fighter’s intensity. If the team—rocking the tattoo/bandanna/scowl uniform of the modern line cook—has inherited the swagger of its leader, they channel most of it onto the plate. The “club sandwich”—a soft, saucy amalgam of pork jowl, shrimp paste, and quail egg—detonates across the palate in waves of sugar, salt, and fat. Pork dumplings come enhanced by the sweetness of strawberry hoisin, the funk and crunch of braised pig ears, and the explosive visuals of a Pollock plating. It’s stoner food with a PhD.

From my perch at the bar, I watch a rotating cast of chefs assemble the famous Korean lasagna: an Asian-inflected ragù made with forty-five-day-aged Galician ox, layered over sheets of pasta, and goosed with a cardamom-spiked béchamel, kimchi-tomato puree, and coconut powder. (They call it Korean, but I count at least six flags planted on the plate.) One sweaty chef in a bandanna turns it into an MMA demonstration, arm-barring and hammerfisting his way through the saucy mass. The young Asian woman who takes over uses tight, precise movements to build this geologic pasta invention, more sculpture than collision. It’s the kind of counter spectacle I want in every restaurant. A flotilla of effervescent, citrus-forward cocktails perfectly matched for the occasion makes the food and the scene down all the easier.

StreetXO is an important restaurant in Spain, reinforcing a decade-long groundswell of international restaurants to hit the capital: Punto MX, Kabuki, Soy Kitchen. You won’t find this diversity of riches anywhere in the country, not even cosmopolitan Barcelona. If you want good Thai or Chinese or KoreViet-JapaMexi, you come to the capital.

![]()

Sometimes Old Madrid and New Madrid make surprisingly good bedfellows—like the tangle of businessmen I spot drinking jalapeño-infused gin tonics at 4:00 p.m. on a Friday at Macera, a beautiful new cocktail lab in Malasaña where Narciso Bermejo infuses hundreds of spirits with flavors of the season—wild fennel, chestnut, asparagus. Taken by the owner’s artistry and hospitality, the group vows not to leave until they’ve tried the entire fall lineup.

Other times, strange things can happen when the two worlds combine. One afternoon, I find myself in a windowless locker room with the chef José Andrés and eleven men (and one woman), captains of industry gathered to discuss a business deal that could alter the fate of the free world. One of the suits, a sharp and serious eater who takes great pride in his insider knowledge of Madrid’s sprawling culinary scene, has invited us to the Academia del Despiece, “one of the hottest new places in Madrid. It’s going to blow your mind.”

Javier Bonet, the son of Mallorcan butchers, earned a name for himself at the Sala de Despiece next door, a long marble bar with a reputation for foo]d that strikes the right balance between pleasure and playfulness. The Academia is the next iteration of the Despiece, a three-hour interactive meal served to a single group of diners.

“Chefs from Madrid used to go to Barcelona to look for inspiration,” Bonet tells me, behind him a chalkboard with formulations for mysterious infusions and extractions. “Now it’s the other way around. For the past three or four years, the young chefs in Madrid have been driving the creative conversation in Spain.”

Apparently, that conversation involves uniforms for the diner. Staff pass out rubber aprons for us to wear, and the suits begrudgingly slip them over their Massimo Dutti jackets. Bonet tells us to surrender our cell phones and personal belongings in little safes before entering the dining room. The room tenses up. People look at the boss man. “Why would we do that?” he asks, mildly annoyed. José, sensing mutiny, drops his phone into the safe. “¡Vámonos!”

We sit at a single long white table in a room made to look like the inside of a meat locker. Everyone is given a set of tools: knives, spatula, metal chopsticks, a mini kitchen torch. The concept starts to take shape: The sala de despiece is the room where animals are butchered, and we are now temporarily enrolled as students in the academy.

Before each course, the lights dim, sounds come pumped in from hidden speakers, and instructional videos are projected onto the table. Students must use their tools and their wits to add the finishing touches to the day’s dishes—sometimes it’s as simple as adding clipped herbs to a vegetable composition, other dishes require more finesse, like toasting a scallop “marshmallow” over an open fire.

Somewhere near course three of twelve, the suits start to stir.

“I didn’t know I was going to have to kill my own lunch.”

“It’s just not comfortable.”

“Would it kill them to put a couple of pillows out?”

“We can’t talk. You can only talk about the food.”

“I love to eat, but I don’t want to talk about food for three hours.”

Everything is meant to be interactive, expansive, genre-bending, but the food falls short—underseasoned, mismatched flavors, a puzzling progression of dishes. Bonet’s creative drive is hugely admirable, but the shortcomings reflect a larger problem in post-Bulli Spain, one where the rabid search for culinary innovation often outweighs the objective to serve paying customers delicious food in a comfortable setting. You can only eat so many spherified tortillas and deconstructed patatas bravas before you pine for the real thing.

Ferran and Albert Adrià’s pioneering work at El Bulli freed Spanish chefs from the shackles of tradition and the formalities of haute cuisine, but it also created an arms race of innovation that doesn’t always make for great dining. Chefs do R&D in laboratories and forge esoteric interdisciplinary collaborations—with structural engineers and marine scientists and Parisian perfumists—and share the discoveries ad nauseam at culinary conferences around the country.

Sometimes the results are stunning, but often they can be punishing. At Sublimotion in Ibiza, Paco Roncero charges diners $1,800 per person for a theatrical meal filled with holograms and self-mixing cocktails—a dinner which he has called “the cheapest life-changing experience anyone can have.” This type of attitude has long threatened certain unhinged strains of Spanish gastronomy. Serving seafood on top of an iPad with a loop of the ocean playing isn’t innovative; piping in music of rustling leaves while you eat some autumnal composition doesn’t make the squash soufflé taste more like squash. You can’t eat smoke and mirrors.

As the chef at Lhardy told me as we discussed my eating itinerary: “You have young chefs leaving culinary school playing with siphons and nitrogen and they can’t even cook lentils.”

Dessert arrives for the disgruntled students: a painter’s palette of matcha tea powder, Pop Rocks, fruity sauces. The room perks up. Soon cuff links clank and ties swing as the class excitedly paints, sculpts, and shapes edible works of art. And right before we are about to devour our creations, we are instructed to pass our plates to the left. The whole room sighs in unison.

![]()

You can feast for hours at a single table in Madrid and linger over coffee and digestivos until the sun goes down and rises again, but I always come back to that same formula: walking and eating, movement to maximize the feast for all the senses. And the more I move about Madrid, the more I begin to see it not as a sprawling metropolis but as one endless pastiche of pueblos.

In Chueca, Madrid’s gay district, bearded bears drink wine and listen to jazz in cozy cafés. Next door, in hip Malasaña, the wine is traded for Negronis, the Coltrane for Kendrick Lamar, the soft pillows for distressed folding chairs. The upwardly mobile slurp oysters and champagne at the stands of the San Miguel market; the downtrodden take shelter in Vallecas and Villaverde, the outskirts of the city where a beer still buys you a free bite. Occasionally these frames in the comic strip of Madrid converge, like on Sundays at El Rastro, where princes and prostitutes and the penniless pluck what they can from Spain’s largest flea market. (Beyond cocido, maybe it’s the love of a bargain that binds Spain most convincingly.)

Maybe that’s been my problem all along—looking for the soul of the city as if it were Waldo, occupying some hidden part of the urban landscape. Or the fact that Madrid doesn’t conform to some easily articulated identity, one that I can describe in a few sentences to friends when they ask me about my trip. The great cities of the world are both canvas and palette; it’s up to us to figure out the picture we want to paint.

MADRID IS NOT A DENSE METROPOLIS, BUT AN ENDLESS PASTICHE OF PUEBLOS.

![]()

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

I like to paint mine on the other side of Retiro, in Lavapiés, a web of narrow, hilly streets where a colorful coalition of students, young professionals, and immigrants converge—nearly all of them adopted citizens of Madrid. The neighborhood trades in cortados and curry, punk rock and pawnshops, ignorant of the whims of the more self-conscious corners of the city.

Here, you don’t follow suits; you follow dark jeans and plumes of hash smoke. Tonight, that smoke and those jeans belong to Liliana López Sánchez and Sergio Fanjul, a hard-puffing young couple who have been living in the neighborhood for the past seven years. We are on the hunt for a particular breed of bar, according to Sergio an animal threatened with extinction in the twenty-first century: the grasabar.

GRASABAR (def): A dive bar whose decided lack of ambiance is overshadowed by cheap booze and fatty food. Common characteristics: waxy napkins, hospital lighting, surly bartenders, the acrid aroma of reused oil. See also Bar Manolo, Bar Paco, bareto, bar de toda la vida.

Sergio is Asturian, born and raised in Oviedo, but has lived in Madrid for years, working as a journalist for El País. Like most Spaniards his age, he’s quick with a joke or to light up your smoke—exactly the guy you want leading a grasabar offensive.

“A lot of the grasabares in the neighborhood have been bought in recent years by young entrepreneurs. They change the bright lights for lower wattage, make a few other small adaptations, and raise the prices. The real thing is a dying breed.”

We start a few steps from the Lavapiés metro stop, at a place called Bar Madroña. Tube lights, gurgling oil, bad pictures of the menu items out front: textbook.

Once the neighborhood fishmonger, the space was transformed into a family-run bar back in the 1960s. The menu on the wall reads like a greatest hits of Spanish bar food: fried potatoes, anchovies, ensaladilla rusa, stewed tripe, fried calamari, bocadillos packed with every pig part conceivable.

Two Chinese guys play pai gow and chew on chicharrones. Back on the plancha, the wife renders a mountain of bacon with a giant spatula.

A drink gets you a free bite—in this case wedges of fried potatoes, reheated in the microwave and covered in squiggles of an unidentifiable sauce. A second drink brings a plate of chicken wings, sweating out fat and gelatin onto the plate. But we’re here for the albóndigas, the springy pork meatballs, which come bathed in a dark yellow sauce with hints of curry spices—a nod to the neighborhood’s constantly evolving demographic.

“Sometimes it feels like nobody in Madrid is actually from Madrid,” says Sergio. “They adapt to the city and make it theirs, but the idea of a native Madrid culture isn’t as clear here as it is elsewhere in Spain. Maybe that’s why Madrid doesn’t sell itself as well as Barcelona.” I tell him about my pueblo posit—that Madrid is a patchwork of little villages—and he nods his head: “Madrid es un pueblo sin fin.” An endless town.

Liliana is from Barcelona, but moved to the capital in 1998 to work in television. “My first year was rough. I missed the sea and the mountains and the whole Mediterranean vibe. But Madrid grew on me, especially the social life. In Catalunya, nobody goes out during the week, and when they do go out, groups don’t mix.” Everywhere you turn in Madrid, you see large groups moving about the city, splintering and reforming throughout the evening, a constantly evolving force of eaters and drinkers who wouldn’t think of going from the office to home without a beer and a tapa.

We move up the street to Café Melo’s, a Lavapiés institution—stampeded from the moment the metal shutter comes up at 8:00 p.m. The place is loosely Galician, and the entire menu—all eight dishes—is built around four key ingredients from the region: Padrón peppers, blood sausage, tetilla (a cow’s milk cheese shaped like a woman’s breast), and lacón, salted and dried pork shoulder—sweeter and less intense than traditional Spanish jamón.

Presiding over the chaos of abandoned plates and cries for more is Ramón, captain of this sweaty closet of a bar since 1979. “He’s famous in the neighborhood for his prodigious memory,” says Txema. “He never writes anything down, and always remembers exactly what you ate and drank.”

You can eat fried Padrón peppers or a convincing croqueta roughly twice the size of every other croqueta in Spain, but the real star of the menu, the reason why the place buckles at the knees at any given hour, is the zapatilla, a melted ham and cheese sandwich of Flintstonian dimensions. A young woman works a large griddle paved with thick slices of ham and melting blankets of tetilla. It looks like she has enough protein to make four or five sandwiches for the hungry crowds, but all of this material is stacked and wedged between two massive slices of toasted bread and served as a single zapatilla. The name, meaning slipper, must be ironic; the three of us struggle to put down one among us. It’s equal parts art and science: the art in the layered beauty of the melted beast; the science in its place as a preemptive strike against tomorrow’s hangover.

We ask for the bill and Mr. Memory doesn’t blink. “Six beers, two wines, two croquetas and a zapatilla. Twenty-eight euros.” It’s only as we waddle out that I spot the sign: PORTIONS HERE ARE ABUNDANT. PLEASE, ORDER WITH MODERATION.

We end the crawl in El Chiscón, a grasabar covered in thirty-six posters, each one announcing the same message in a different language: No smoking joints inside. We order calimochos, the drunkmaker of the Spanish youth: box wine mixed with off-brand cola, served over ice in one-liter glasses. A party in a plastic bathtub.

Liliana surveys the scene, smiles like someone half her age. “Now it’s hard for me to go back to Barcelona.” I can’t promise that it will be the same for me, but I can start to see her dilemma.

Outside, everyone smokes and rails against the assholes in government in a flurry of accents: the clipped-consonant patter of Andalusia brushes up against the melodic rise and fall of Galicia, which gives way to the sun-soaked syllables of the Canarias. Txema tells me that before I board the train tomorrow, I must eat the gallinejas on Calle de Embajadores—fried lamb ventricles, a sacred weekend ritual, he assures me. (Nine hours later, as I chew through the gristle, I will curse this parting advice.)

As I wobble home at 2:30 a.m., the neighborhood shows no signs of slowing down. The kebab kings slice their spicy towers of spinning meat; the hash dealers do brisk business on the dark street corners. Inside the bars that dot these hills, most have traded beer and wine for gin tonics and whiskey colas. Beneath the curtain of a half-shuttered storefront, the man of Melo’s with the prodigious memory scrapes the last of the caramelized cheese scraps from his battle-tested griddle.

Somewhere out there, in the never-ending pueblo of Madrid, a man with a mohawk shows his cooks how to turn a cocktail into a salad, a mezcal-soaked restaurant owner captivates clients with tales of the greatness of Spain, a pot of simmering bones give up their marrow for tomorrow, and a group of suits still crisp from the workday decide there's enough time for one last round.

Small Plates

Matt Goulding

What began as an inventive way to cover drinks in the fly-infested heat of southern Spain has turned into a style of eating that has fundamentally altered dining in this country and beyond. Tapas may have been born in Andalusia, but small plates reign all over the Iberian Peninsula. From Basque pintxos to Galician seafood to Andalusian fry bars, regional styles abound, but the following represent a tasty (if incomplete) snapshot of the titans of the Spanish tapas world.

Matt Goulding

PATATAS BRAVAS

Fried potatoes with spicy paprika sauce

ALBÓNDIGAS

Braised pork meatballs

CHIPIS A LA ANDALUZA

Fried baby squid or calamari

ALMEJAS A LA MARINERA

Clams cooked with garlic and white wine

SETAS AL AJILLO

Garlic-heavy sautéed mushrooms

ANCHOAS

Cured anchovies from Cantabria

BOQUERONES

Marinated white anchovies

ALCACHOFAS FRITAS

Artichokes fried in olive oil

Matt Goulding

PIMIENTOS DE PADRÓN

Fried Padrón peppers with coarse salt

NAVAJAS A LA PLANCHA

Razor clams cooked on the flattop

CROQUETAS DE JAMÓN

Cured ham croquettes

ACEITUNAS

Marinated olives

SARDINAS EN ESCABECHE

Sardines in garlic, herbs, and vinegar

RULES OF THE CRAWL:

![]() Find the balance. For every crispy croqueta you'll want a briny clam to keep your palate primed for more.

Find the balance. For every crispy croqueta you'll want a briny clam to keep your palate primed for more.

![]() Keep moving. The point is to work your way from one bar to the next, sampling the best of each.

Keep moving. The point is to work your way from one bar to the next, sampling the best of each.

![]() Fill it up. Tapas culture is as much about drinking as eating. Not getting drunk, but enjoying good wine, sherry, or your poison of choice.

Fill it up. Tapas culture is as much about drinking as eating. Not getting drunk, but enjoying good wine, sherry, or your poison of choice.

TORTILLA DE PATATAS

Potato omelet

GAMBAS AL AJILLO

Shrimp sautéed in spicy garlic oil

Matt Goulding

9:00p.m.

–

STAY LOOSE

This ain’t Paris circa 1968. Enjoyment and cost should have a direct relationship in the dining world, so let loose. Dress casual (anything beyond a T-shirt and jeans will do), make jokes, tell stories, get drunk. Have a big night. The service staff and the chefs will thank you for it.

9:30p.m.

–

SMOKE AND MIRRORS

The meal starts with a flurry of small bites that deliver bursts of taste, texture, and surprise. (That stone ain’t a stone. It’s a potato!) The bait and switch is a well-worn Spanish conceit. Delightful when it’s delicious; a buzzkill when it leaves you missing the genuine article.

10:05p.m.

–

BANISH THE BREAD

The bread basket looks like a box of crayons, colored with everything from tomatoes to saffron to squid ink. Don’t be fooled: You have three hours and twenty courses in front of you, and even the best bread is still your foe. There’s nothing worse than being too full for the finale.

11:20p.m.

–

DIVE DEEP

Spanish chefs value the quality of their seafood above all, and tasting menus typically play out like a marine geography lesson: Galician razor clams, Catalan red shrimp, tuna from Cádiz. Most meals will end with a single plate of pristine protein—suckling pig or lamb or even game.

12:15a.m.

–

HALF-WINE IS FINE

Do a wine pairing and you’ll end up with a dozen vintages on your table, which can be thrilling or overwhelming, depending on how you roll. A more restrained option is a half-wine pairing, or sharing a few bottles. The best restaurants go beyond wine and play with sake, beer, and spirits.

1:00a.m.

–

TOUR THE TEMPLE

Why yes, the chef would be happy to show you the kitchen. Expect to find a silent, sparkling, lab-like environment. What’s that crazy device, you ask? (One of so many!) It’s the machine responsible for all those distillations you didn’t know you were enjoying. Score one for science!

Michael Magers (lead photographer)

Matt Goulding

NOT INVENTED, JUST PERFECTED

Gin and tonic may have been born in India in the nineteenth century, but “gin tonic” is a uniquely Spanish culture, one that began to take shape in the early 2000s in corners of Madrid and Barcelona. Now, it’s common to find even dive bars selling dozens of customized creations.

SIZE MATTERS

No highball or rocks glasses, a Spanish gin tonic must be made in a big-bellied wineglass, like the ones used for powerful reds. Same goes for the ice: normal ice means instant dilution. Good bars serve two to three massive cubes that will hold the cold.

MIX AND MATCH

Bars stock up to fifty gins, half a dozen tonics, and an arsenal of garnishes: citrus peel, fresh herbs (thyme, rosemary, basil), whole spices (cardamom, peppercorns, juniper), and fresh produce (cucumber, ginger, chile). You want harmony between gin, tonic, and garnish.

DRINK IT LIKE A SPANIARD

Spaniards don’t drink gin tonics (or any hard liquor) before a meal (just one of these on an empty stomach will get you going). Gin tonics are most commonly consumed as a digestivo after a big meal, or at the bar in the early-morning hours.