IN 1839, ITS FIRST YEAR, OK WAS NOTHING MORE THAN A joke. It was just one among many clever and not-so-clever abbreviations passed around by newspaper editors aiming to be funny. And as the next year began, there was nothing to suggest that OK was destined for greatness. Just the opposite; OK was poised to die out in obscurity, like OFM (our first men), SP (small potatoes), GC (gin cocktail), and OK’s fellow in misspelling, OW (all right), whenever the joke would get stale and bored editors would be ready to try other amusements.

For OK, then, the year 1840 began uneventfully, with just a jokey OK here and a jokey OK there. But then a funny thing happened: a presidential election. Thanks to the accident of an election with unparalleled popular participation, OK was drafted to serve in the campaign of 1840. And though the OK candidate lost, by the end of the year OK itself was a winner, indelibly impressed in the American psyche across the length and breadth of the Republic. Or perhaps more accurately, just running amok.

For OK wasn’t content to abide by a single meaning in 1840. Once the idea had been planted that OK could mean something in addition to “all correct,” politicians, editors, and would-be poets outdid each other in conjuring fanciful new meanings for the two letters. Where OK had been in danger of fading into obscurity at the start of 1840, by year’s end it was in danger of dissipating from meaning too many things to too many people. As luck would have it, it was saved from the latter fate only by a hoax about its origin—also involved with the election, and also in 1840.

Never before or since that year of 1840 has OK seen such radical change. Evolution, as Charles Darwin was to describe the process two decades later, is a good way to understand the development of OK in that memorable year. The bizarre politicking and editorializing of 1840 created an unusual temporary environment in which the fittest abbreviation to survive was none other than OK.

The campaign of 1840 was a spectacular one, famous for its rallies, slogans, and symbols, in which OK played a prominent part.

The stage was set for OK in 1840 because it happened that Martin Van Buren was president of the United States and seeking a second term. And it happened that his home, where he was born and where he lived while not in Washington, was the upstate New York town of Kinderhook. Earlier in his political career Van Buren was known as the “Little Wizard” or “Little Magician” for his skill in building political coalitions (and for his short stature; he was five foot six). Now, noticing K in the name of his hometown, and noticing that Van Buren was advanced enough in age no longer to be called a young man (he was fifty-seven in 1840), someone in the Democratic Tammany political organization of New York City put that K together with the previous year’s OK, calling Van Buren “Old Kinderhook.” That nickname picked up the 1839 abbreviation like a magnet. OK now could have a double meaning: Old Kinderhook was all correct.

And Van Buren needed the power of OK, because he faced an opponent with some of the most effective campaign slogans of all time. The Whig candidate, old William Henry Harrison, campaigned on “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too,” Tippecanoe reminding voters of General Harrison’s victory over Indians at Indiana’s Tippecanoe River in 1811, and John Tyler being Harrison’s vice presidential candidate. But even more effective was the Harrison slogan “Log Cabin and Hard Cider.” Strangely enough, it came from a derisive invention by an anti-Harrison journalist, John de Ziska, in the Baltimore Republican of December 11, 1839:

Give him [Harrison] a barrel of hard cider, and settle a pension of two thousand a year on him, and my word for it, he will sit the remainder of his days in his log cabin by the side of a “sea coal” fire, and study moral philosophy.

After other Democrats picked up on this and repeated the intended insult, the Whigs decided to turn it around and make the most of it, portraying Harrison as a man of the people, supposedly living in a log cabin in Indiana with a barrel of hard cider outside. Harrison, in fact, lived in a grand Indiana mansion, but ever since the election of Andrew Jackson, Van Buren’s predecessor as president, an association with a log cabin was highly useful in demonstrating that a candidate was a man of the people. So popular was the image of “Log Cabin and Hard Cider” that it even was depicted on elegant tea sets.

The rough and ready Tammany Society of New York City was at the center of Democratic politicking, having supported Jackson for his two terms as well as the election in 1836 of Jackson’s hand-picked successor, Van Buren. On March 23, 1840, exactly a year after the birth of OK, a Tammany newspaper, the New Era, carried this announcement:

THE DEMOCRATIC O.K. CLUB, are hereby ordered to meet at the House of Jacob Colvin, 245 Grand Street, on Tuesday evening, 24th inst. at 7 o’clock.

Punctual attendance is requested.

By order,

WILLIAM STOKELY, President

John H. Low, Secretary

And what happened at that meeting? We can guess what they talked about from what came next. Like the other Tammany clubs in New York City—the Butt Enders, the Huge Paws, the Locofocos, the Simon Pures, the Tammany Temple, and oh yes, the Van Buren Association—the O.K. Club literally fought its Whig enemies. On March 27, the New Era used OK to tell its Tammany readers about a Whig meeting they ought to attend:

The British Whig papers of this city contain a call for a public meeting to be held this evening in Masonic hall.… Those “who would render the right of universal suffrage easy of exercise and convenient to all” are requested according to the call to be in attendance. To all such we say go.

And to that meeting they went, the O.K. Club in particular. According to the Newark Daily Advertiser, one of the many newspapers that next day reported the encounter:

The doors being closed, some 15 or 20 Whigs remained in conversation, when some 60 rowdies burst suddenly in upon them with personal violence—both parties tearing away banisters and benches for weapons. A posse of watchmen soon rushed in and arrested the ringleaders. The war cry of the locofocos was O.K., the two letters paraded at the head of an inflammatory article in the New Era of the morning. “Down with the whigs, boys, O.K.” was the shout of these poor, deluded men. Such were the fearful beginnings of the French Revolution!

Not to be outdone, the Whigs responded with a twist on O.K. The Daily Express commented a few days later,

“O.K.”—Many are puzzled to know the definition of these mysterious letters. It is Arabic, reads backwards, and means kicked out —of Masonic Hall. Vide Loco Foco Dictionary.

In turn, the Democratic New Era quickly picked up on K.O.:

K.O.—O.K.—The Ohio City Transcript (federal) is K.O. (kicked over) and defunct—which is held to be O.K. (oll korrect).

O.K. figured in a Democratic parade on April 10. According to the New Era the next day, marchers carried a banner showing

a huge Cabbage mounted upon legs, singing out O.K. to General Harrison, and chasing him like a racer.

At that point, the Tammany adoption of O.K. was something of a mystery. Why would a political club adopt a misspelled abbreviation for “all correct” as its war cry? On May 27 the New Era provided the explanation:

JACKSON BREAST PIN. —We acknowledge the receipt of a very pretty gold Pin, representing the “old white hat with a crape” such as is worn by the hero of New Orleans, and having upon it the (to the “Whigs”) very frightful letters O.K., significant of the birthplace of Martin Van Buren, old Kinderhook, as also the rallying word of the Democracy of the late election, “all correct.” It can be purchased at Mr. P. L. Fierty’s, 486 Pearl Street. Those who wear them should bear in mind that it will require their most strenuous exertions between this and autumn, to make all things O.K.

Though the Democrats tried to keep O.K. for themselves, the Whigs made use of it too, sometimes in reporting election successes (as in “Cleveland O.K.!!”), sometimes in mockingly reinterpreting the initials, as in this from the Whig Daily Express:

O.K., i.e. “Ole Korrect,” Out of “Kash,” Out of “Kredit,” Out of “Karacter,” and Out of “Klothes.”

It wasn’t just in New York either, though New York’s Tammany is where the political OK began. But the campaign brought OK far afield from the eastern cities. A history of Ohio tells of a memorable day in Champaign County of west-central Ohio, population 16,720 in 1840:

Urbana was early somewhat famed for its political conventions. The largest probably ever held in the county was September 15, 1840, in the Harrison campaign, when an immense multitude assembled from counties all around. A cavalcade miles in extent met General Harrison and escorted him from the west to the Public Square, where he was introduced to the people by Moses B. Corwin and made a speech two hours in length. He was at this time sixty-seven years of age, but his delivery was clear and distinct. Dinner was had in the grove of Mr. John A. Ward, father of the sculptor, in the southwest part of the town, where twelve tables, each over 300 feet long, had been erected and laden with provisions. Oxen and sheep were barbecued, and an abundance of cider supplied the drink for the day. In the evening addresses were made by Arthur Elliott, ex-Governor Metcalf, of Kentucky, who wore a buckskin hunting shirt, Mr. Chambers, from Louisiana, and Richard Douglass, of Chillicothe. The day was one of great hilarity and excitement. The delegations and processions had every conceivable mode of conveyance and carried flags and emblems with various strange mottoes and devices. Among them was a banner or board, on which was this sentence:

(The box is in the original.) And the 1891 history book concludes: “This was the origin of the use of the letters ‘O. K.,’ not uncommon in our own time.” It wasn’t the origin, but the denizens of Champaign County may be pardoned for not perusing the Boston newspapers of 1839.

Meanwhile, in Columbus, Ohio, the Straight-out Harrisonian offered this distinction in its issue of October 9, 1840:

The Whig definition of O.K. is—Oll Koming. Locofoco [Democratic] definition—Orful Katastrophe.

With pundits and politicians gleefully appropriating OK for their peculiar purposes, it began to spin out of control. The Oxford English Dictionary quotes the Lexington Intelligencer of October 9:

O.K. Perhaps no two letters have ever been made the initials of as many words as O.K.… When first used they were said to mean Out of Kash, (cash); more recently they have been made to stand for Oll Korrect, Oll Koming, Oll Konfirmed, &c. &c.

Exemplifying the Intelligencer’s claim, the Democratic New Era was happy to join in the imaginative interpretations of OK. On the eve of the election, the New Era printed a letter proposing nearly a dozen politically charged versions:

Mr. Editor—Everything that we see, hear, or discourse of, is O.K., any thing otherwise is out of my power to imagine, and from mature consideration, I have arrived at the following conclusions:

That Harrison, being the friend and advocate of Hard Cider, which (no doubt he freely uses) is O.K. “Olways Korned.”

That the “immortal Dan” [Webster] being Harrison’s adviser in all political matters, is O.K. because he is Harrison’s “own Konfidential.”

That “Henry [Clay] of the West” is likewise O.K. derived from no other source but his name “Old Klay.”

THAT MARTIN VAN BUREN, is O.K. because what he says is OLWAYS CREDITED, and what he does is OLL KORRECT.

…

That General Jackson is O.K. because he is “Olways Kandid.”

…

That the whigs engaged in committing the frauds on the Ballot Box in the fall of ’33, and spring of ’34, are O.K. because they are “Orful Konspirators.”

That Moses H. Grinnell, the president candidate for Congress, is O.K. because he is at present “Orfully Konfused.”

…

That my article is O.K. because it is Oll composed.

When the election of 1840 was over and Old Kinderhook had lost, Charles Gordon Greene of the Boston Morning Post, the daddy of OK, offered some ruefully humorous new interpretations for OK. In the issue of November 28:

O.K.—After the 4th of March next [with the inauguration of Whig President William Henry Harrison], these expressive initials will signify all kwarrelling. The whig house, divided against itself, cannot stand.

And on December 7:

Why shall we be O.K. after the first of January next? Because we shall be an Ousted Kernel [Greene himself was known as Colonel Greene].

An exuberant writer, known only as C.B., summed up the situation of OK a year and a half after its birth in a poem that was published in the Boston Daily Times on December 15, 1840, and rediscovered by researcher Richard Walser in the 1960s. The poem refers to the presidential election where editor Greene was on the losing side, and to much else. There is no better way to show how widely by then OK had spread its fame and its meanings than to reprint it here in full. The particular political posturings matter less for our purpose than the inventive uses for OK.

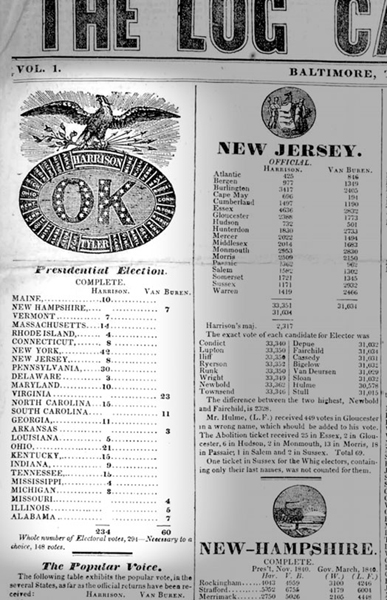

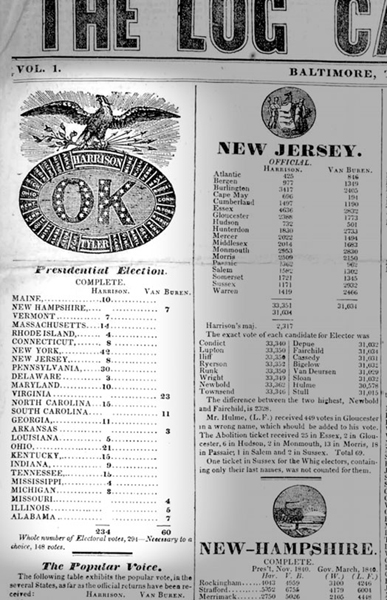

The Log Cabin Advocate of December 15, 1840

Triumphant Pro-Harrison Newspaper Reporting Election Results

PHOTO BY HERITAGE AUCTION GALLERIES.

What is’t that ails the people, Joe?

They’re in a kurious way,

For every where I chance to go,

There’s nothing but o.k.

They do not use the alphabet,

What e’er they wish to say,

And all the letters they forget,

Except the o. and k.

I’ve seen them on the Atlas’ page,

And also in the Post,

When both were boiling o’er with rage,

To see which fibbed the most.

The Major [editor of the Atlas] has kome off the best;

The Kernel [editor Greene] is surprised!

The one it seems meant oll korrect,

The other, oll kapsized!

Processions have been all the go,

And illuminations tall;

Hand bills were headed with k. o.,

Which means, they say, kome oll!

The way the people sallied out,

Was a kaution to the lazy;

And when o. k. I heard them shout,

I thought it meant oll krazy.

They say that Blair, the editor,

Is o. k. off to Kuba,

But what it is he’s gone there for,

Is nothing but false rumor.

K. k., the konkered kandidate,

Must yield to freedom’s right;

He’s a handsome man, but k. k. k.,

He kould not kome it kwite!

There’s Butler too, in whom, Whigs say,

No man kan safely trust;

They tell him oft to k. k. k.,

Keep karefully his krust.

The people thought when he took hold

To prove that votes were bought,

A monstrous fraud would kwick be told,

With Whigs, o. k., oll kaught!

The Merchants too have been o. k.,

Hard times have loudly said it;

It long has been too much their way,

To buy and sell on kredit.

They’ll now adopt as bad a kourse,

Be o. k., over cautious,

Which constantly will prove a source

Of miseries and tortures.

The President, that big steam ship,

Has acted very droll;

She was o. k. her second trip,

For she got out of koal.

K. k. k. is the proper name

Kunard kan konquer on the main

Each steamer that it floats.

The would be swell, whose purse is drained,

Who kannot kut a dash:

To see o. k., his heart is pained,

Bekause he’s out of kash;

He e’en resolved to kut his throat,

But feels somewhat afraid,

He views o. k., his orful koat,

And Earle’s last bill unpaid.

Whene’er you read an accident,

’Tis o. k. that you see;

An orrible kalamity,—

Orful katastrophe.

And when the people rave and rant

About some trifling thing,

You’ll find it’s all o. k., oll kant,

Which makes the kountry ring.

They’re running k. k.’s in the street,

And handsomely they go;

I’ve heard them kalled konvenient Kabs,

By one who ought to know:—

He said he rode in one, one day,

When heavily it stormed,

And thought them just the thing for those

Who are o. k., oll korned [drunk].

The beauteous girls, unkonsciously,

Kause many sad regrets,

They love so well to be o. k.,

Such orrible kokettes!

I know of one whose flaxen hair,

Hangs down o. k., oll kurly;

Her lips the sweets of Eden bear,

And more,—she ne’er speaks surly.

To win this angel’s heart and hand,

I used o. k., oll kunning;

And thought to make my konverse grand,

By great attempts at punning.

’Twas all in vain,—she merely said

She liked me as a friend,

And now she’s gulling a young blade,

Whose love thus sad will end.

The kry of o. k. rends the air,

From north to south it goes,—

It’s on a shop in Brattle Square,

Where negroes sell old klothes!

The world ne’er saw such kurious times,

Since politics were born,—

You’ll see o. k. on grain-store signs,

Which stands for Oats and Korn!

This theme has on Pegasus’ way

Most wantonly obtruded,

And now, with joy, I have to say

It’s o. k. oll konkluded.

Yet four more lines I needs must write,

From which there’s no retreat,

O. k. again I must endite,

And—lo! it’s oll komplete!

Three days later, referring to a reprint of the poem in a weekly newspaper, the Times commented: “O.K. our readers will certainly admit is o.k.” Clearly, the core meaning of OK remained intact, but it was threatening to expand its periphery to encompass a large chunk of the language.

By its very nature, OK had already violated the first rule for survival of a vocabulary creation: blend in, be inconspicuous. Conspicuous coinages can’t compete. Clever comments aren’t incorporated. Jokes don’t blend into the common vocabulary.

The evidence for this principle is overwhelming (and given at length in my 2002 book Predicting New Words: The Secrets of Their Success). For just one example: In the 1980s Rich Hall published five books of sniglets, “words that don’t appear in the dictionary but should,” such as mustgo, “any item of food that has been sitting in the refrigerator so long it has become a science project.” Of all his invented words, the only one that ever caught on was sniglets itself. The others were too clever, too conspicuous.

And OK was conspicuous. It kalled attention to itself by its misspelling, by its use of the konspikuous K (katching, isn’t it?), and by its origin as a joke, which in turn inspired other jokes. Indeed, OK called ekstreme attention to itself. It’s hard to imagine any other koinage of American English evoking a 112-line poem.

Paradoxically, as 1840 drew to a close, the very prominence of OK put it in danger of demise. With so conspicuous an appearance, and such possibilities for dispersion of meaning, OK was on the verge of vanishing into thin air, leaving behind only its smile, a chuckle to be known only to historians of early nineteenth-century American politics. Instead, it was saved by yet another joke, the subject of the next chapter.