3

HOW AGILE DO YOU WANT TO BE?

Spoiler alert: the title of this chapter is a trick question. You will soon see why. But let’s start with a different kind of journey altogether.

In February of 1982, Mark Allen was twenty-four years old and had been out of college for two years. A strong swimmer, he had been working as a lifeguard in San Diego, participating successfully in occasional lifeguard competitions. San Diego was the home of modern-day triathlons, long-distance combinations of swimming, bicycling, and running events. The sport was still new, and many questioned whether it would survive.

But Allen was captivated. That month, he decided he wanted to compete in the sixth Ironman World Championship in Hawaii, coming up in October. It would be a grueling race: a 2.4-mile (3.86 kilometer) swim, followed by a 112-mile (180.25 kilometer) bicycle ride, and then a full 26.22-mile (42.20 kilometer) marathon run.

Allen started by benchmarking how fast the world’s best triathletes were running and learned that they were doing close to five-minute miles. So that’s what he did. Running at that rate sent his heart rate to 190 beats a minute, but he trusted in the no pain, no gain coaching philosophy of the times. Unfortunately, it didn’t work. He entered but did not complete the 1982 event.

For two years thereafter, Allen pushed himself harder and harder. “I went too hard all the time,” he later told an interviewer. “Sometimes I did have good results in those races, because you get a certain type of fitness out of that. Long term, it was burning me out, and I was getting some minor injury things that I’d have to take a few days off. After almost every race I ended up getting sick.”1

Allen then met a coach named Phil Maffetone, who had a different training philosophy. Maffetone recommended working at a challenging but sustainable pace, known as the maximum aerobic heart rate. There are sophisticated methods for determining this level for a particular individual, including expired gas analysis or blood lactate levels, but they require expensive equipment and analysis. Maffetone had developed adequate approximations using a few simple variables such as age, physical conditioning, experience, and medical conditions.

Using these guidelines, Allen determined that his target heart rate should be about 155 beats per minute. Running at 155 beats per minute made him slow down. He went from running 5:30 minute miles to 8:45 minute miles, more than three minutes slower. He felt embarrassed, and he wondered if the training was even working. But he also felt stronger. Instead of dreading his next training session, he began enjoying them:

I got faster very consistently for about three years and then the very top speed slowed down. At some point you’re not going to get any faster. After about three years, at the end of the season I was able to run a 5:30–5:45 pace at 155 beats per minute.… What did change is that the fall-off from mile to mile became less over time. You might do your first mile on the track at 5:30 pace, then the next mile at 5:45, then 6:00, then 6:10, something like that. Over time that fall-off became very small, so I could run two, three, or four miles and the fall-off would only be 10 seconds total, so you start at 5:30, and by the third mile you’re still running 5:35–5:40. There are different levels of fitness—there is speed and there is the ability to hold speed over time.2

Allen trained his body and mind to deal with the three-hour physiological barrier, then the six-hour barrier. When his performance plateaued, he employed a wide range of techniques to take it to the next level, including speed, strength, and endurance training; nutrition improvements; stress management; and sleep guidelines. All of these became part of his integrated system of continuous improvement.

Seven years after failing to complete his first Ironman competition, Mark Allen won the 1989 Ironman World Championship in an epic battle against Dave Scott. From 1988 to 1990, he won twenty-one consecutive races. By 1995, Allen had won six Ironman competitions. Triathlete magazine crowned him “Triathlete of the Year” six times.3 An ESPN poll voted him the Greatest Endurance Athlete of All Time.

His transition from lifeguard to those lofty heights offers remarkable insights into any human transformation—including the creation of an agile business system. Organizations embarking on a transformation to an agile enterprise are like triathletes in training. It’s an ambitious project. There is an optimal pace. It’s likely to take years to come to fruition. But successful companies will be able to do things that few others can even contemplate.

As we will see in this chapter, moreover, the challenges are almost directly analogous. So are the pathways that a company must follow if it is to succeed in determining how far—and how fast—it wants to go.

Challenges

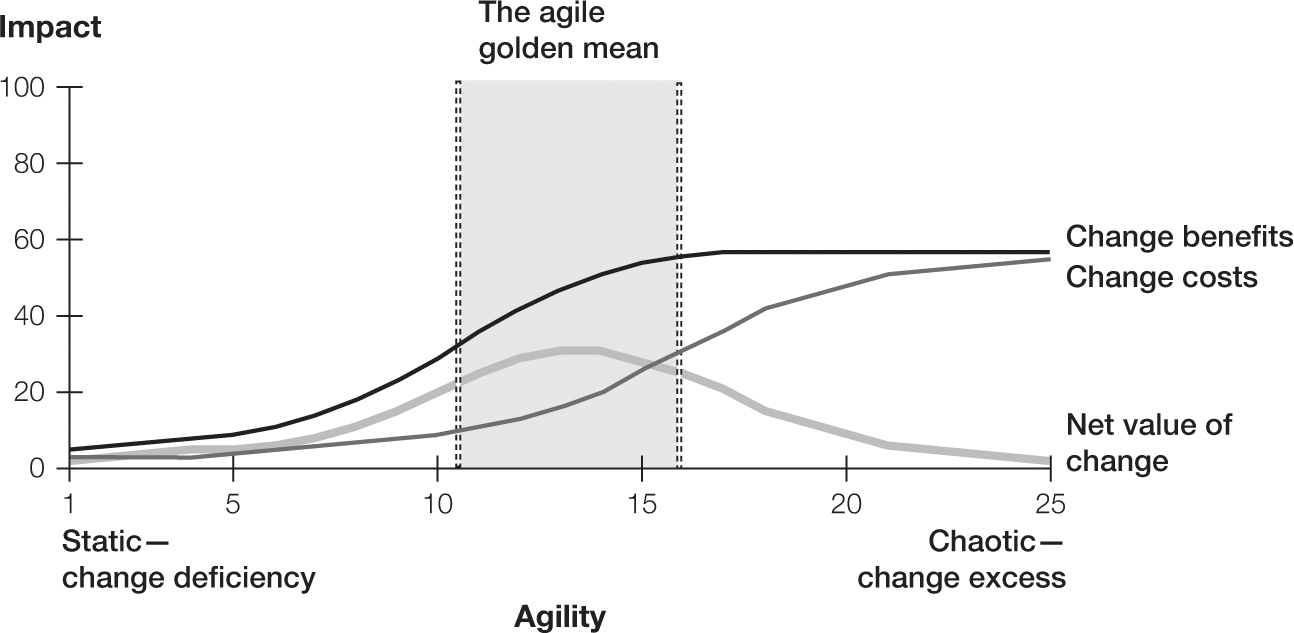

Like the optimal heart rate for an athlete, there is an optimal level of change for every business, and for every activity within a business. Ideally, an agile business system would operate at the golden mean between change deficiency—leading to a static business system that adapts too slowly to survive—and change excess, creating a chaotic business system that constantly risks spinning out of control. When a company is operating in this sweet spot, the benefits of an agile system exceed the costs by the greatest amount, producing the highest net value (the difference between the benefits and the costs of agile) for the business (figure 3-1).

Change Deficiency

Of the two extremes, a static business system is the greater threat for most large companies. Change deficiencies happen more frequently in large organizations, and the impact is more devastating. Bureaucracy slows innovation to a crawl. Sluggish incumbents watch innovative insurgents speed past them. Finding the courage and the investment dollars to catch up with the insurgents grows increasingly improbable. That’s why the average life span of companies on the S&P 500 list has plummeted from sixty years in the 1950s to less than twenty years today, and experts estimate that it could fall to twelve by 2027.4 Horror stories of the crippling declines of once-vigorous companies—Eastman Kodak, RadioShack, Polaroid, Blockbuster, Toys “R” Us, and Xerox—drive terrifying fears of death by disruption.

The agile golden mean

Change Excess

The other extreme, a chaotic business system, is equally dangerous but is more common in small start-ups than in large companies. Research on 3,200 high-growth technology companies shows that the primary cause of failure in fast-moving start-ups is premature scaling—growing too fast before properly validating fundamental business concepts and building repeatable, stabilizing operating systems. Data suggests that start-ups need two or three times as long to validate their market than most founders expect.5

Of course, chaotic systems also afflict large-scale companies. Uber, for example, has been extraordinarily innovative, but its early years were plagued by sloppy operating standards, widely reported in the business press at the time.6 That deficiency led to launching tests of autonomous vehicles without proper permits, false advertising to recruit drivers, accusations of price gouging, claims of sexual harassment, allegations of unethical booking of fake rides at its primary competitor, and privacy violations. Likewise, Tesla’s ingenious CEO, Elon Musk, admitted that his impulsive nature, capricious tweets, and lack of operating experience often created chaos for the company. He set production deadlines and price targets for Tesla’s Model 3 that seemed impossible to meet, and indeed they were. Problems running the business drove Tesla within days of bankruptcy. Musk told 60 Minutes, “Well, I mean punctuality’s not my strong suit. I think, uh, well, why would people think that if I’ve been late on all the other models, that I’d be suddenly on time with this one? … I never made a mass-produced car. How am I supposed to know with precision when it’s going to get done?”7

Finding the sweet spot requires estimates of the benefits and costs of increasing agility. Agility can produce extraordinary benefits, but it requires balance, and the trade-offs should be quantified. Even rough estimates of the benefits and costs can help to set realistic expectations for how much is at stake, how far a company’s agile transition should go, and how fast it should proceed.

Representative benefits typically include the following:

- Greater revenue growth because of better and faster new-product introductions, service improvements, greater pricing power (thanks to higher levels of innovation), new business launches, adding new customers, retaining more customers, and higher customer lifetime values

- Lower costs because of more efficient innovation, fewer write-downs of obsolete inventory, greater ability to attract and retain high-quality people, lower employee turnover, higher morale and productivity, and the elimination of unproductive activities

- Fewer assets because of less work in process and lower inventory levels

The potential costs vary widely from one company to another, but you may encounter any of the following, and so you will want to estimate their effects:

- Transition costs, including the need to invest in new technology, training and coaching costs, and lost productivity while people reorganize and learn new methods and roles

- Efficiency costs, such as lower capacity utilization (to speed up response times), decreased economies of scale, duplicated efforts, the cost of less uniformity in some functions, and the cost of greater experimentation

- Increased risks, such as the risk of more errors resulting from less oversight of individuals with lower skills and capabilities; and the risk of greater variation around forecasts

- Organizational costs, including the cost of coordination across teams, the cost of team colocation, higher turnover of people who don’t fit with agile approaches, and the cost of more frequent changes in assignments and matrix reporting structures

Being up-front about these trade-offs helps to set realistic expectations. It also explains why we repeatedly stress the importance of balance and trade-offs while so many agile gurus seem determined to out-crazy each other with increasingly radical and precipitous recommendations.

Here’s a tip: Before you embark on an agile journey, go online and search for terms such as “agile doesn’t work.” You will see more than 40 million results (we are not making up this number). Sample headlines include “Why Isn’t Agile Working?,” “Back to Waterfall,” “Why ‘Agile’ and Especially Scrum Are Terrible,” and “Why People Give Up on Agile.” Now, nobody should believe everything (or perhaps anything) that they read on the internet. But you should at least check out some of the criticisms, look for recurring themes, and prepare to deal with the challenges.

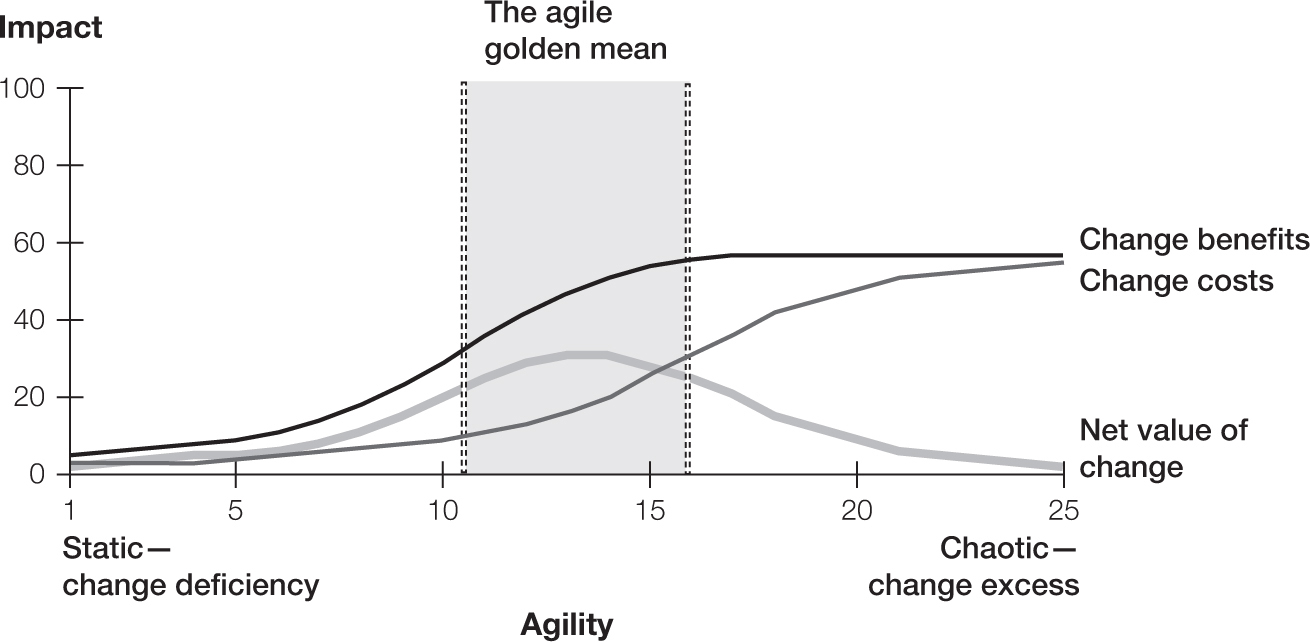

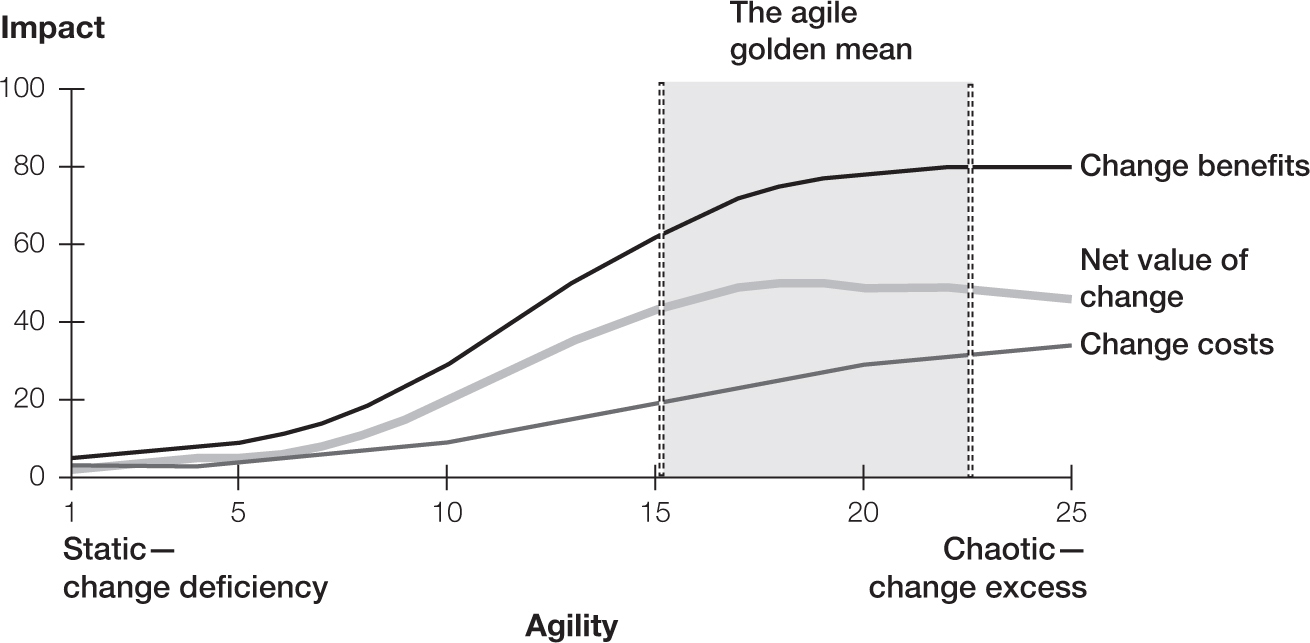

Conceptually, navigating within agile’s golden mean to avoid the dangers of both deficiencies and excesses seems sensible, even simple. Be aware, however, that the golden mean never lies in exactly the same spot for any two companies. The right balance will vary by industry, company, and activity within a business (see figure 3-2). Furthermore, it is likely to change over time and with experience. This is why two of the most common shortcuts to creating an agile enterprise—copying some other company and big-bang initiatives—rarely work. Launching an all-at-once agile transition, for example, requires a guess at the golden mean. But businesses are complex systems that behave in random, unpredictable ways, and predictions usually fail in vague and uncertain conditions. Anyway, we human beings simply aren’t as good at forecasting as we think we are. Dan Lovallo and Daniel Kahneman describe what they call the planning fallacy: people tend to overestimate their own capabilities, exaggerate their ability to shape the future, and underestimate the costs, time, and risks in planning a project.8 Phil Tetlock, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School and coauthor of Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction, suggests that a good starting point is to assume that our predictions are 50 percent accurate, the same as if we were predicting the toss of a coin.9

Typical conditions (top) and favorable agile conditions (bottom)

That’s why big-bang agile restructurings, trendy as they may be, tend to flounder. Leaders may force nearly everyone into agile squads and tribes. They may place people with agile attitudes but little experience in positions that need expertise. They may try to reduce headcount—especially in support and control functions—by 20 to 30 percent. But the golden mean remains elusive. Researchers have now had more than five years to study the results of such programs. Though companies pursuing this approach often add hundreds or thousands of agile teams and reduce the cost of bureaucracy, their overall business agility and results rarely improve.

Pathways to Success

If copying and guessing don’t work, what does? How can a company find its golden mean with the right level of agile and the right rate of change? Think back to Mark Allen. He clarified his goal, winning an Ironman triathlon. He developed critical metrics for tracking his progress. He used those metrics to identify the most important constraints, and he constantly adjusted his program to push through barriers and plateaus. He was thus able to create an integrated system that helped him develop at the proper pace. Let’s look at each of these elements in the context of a business organization.

Determining Your Purpose

Allen didn’t want to get in shape to win more lifeguard competitions, or to lose weight, or to win bodybuilding contests. He wanted to win the Ironman World Championship. Companies need to be equally clear. No company should want to be agile for the sake of being more agile. Agile is a means to an end, and the end is likely to be different for every organization. The tighter the organizational alignment around a clear and shared purpose, the easier it is to trust autonomous teams to do the right things without micromanagement. That’s because everyone is committed to the purpose behind the plans and can adapt effectively to unexpected circumstances.

How you express your company’s purpose matters a great deal. Warby Parker puts it like this: “To offer designer eyewear at a revolutionary price, while leading the way for socially conscious businesses.”10 The people at Warby Parker enjoy significant freedom because the goal is so easy to understand. Barnes & Noble, on the other hand, expressed its purpose this way for many years:

Our mission is to operate the best specialty retail business in America, regardless of the product we sell. Because the product we sell is books, our aspirations must be consistent with the promise and the ideals of the volumes which line our shelves. To say that our mission exists independent of the product we sell is to demean the importance and the distinction of being booksellers.

As booksellers we are determined to be the very best in our business, regardless of the size, pedigree or inclinations of our competitors. We will continue to bring our industry nuances of style and approaches to bookselling which are consistent with our evolving aspirations.

Above all, we expect to be a credit to the communities we serve, a valuable resource to our customers, and a place where our dedicated booksellers can grow and prosper. Toward this end we will not only listen to our customers and booksellers but embrace the idea that the Company is at their service.11

No matter how many times you read the statement, it doesn’t get any easier to understand. Can you imagine agile teams at the company being left on their own to implement that purpose?

There are a couple of purposes, incidentally, that are bad ideas from the beginning: Wanting to be part of a trendy management philosophy. Chopping headcounts without innovating business processes and then blaming the resulting layoffs on agile. It’s better not to do agile at all than to do it for the wrong reasons.

Learning to Measure Agility

Plenty of executives these days would like their companies to be more agile. Some have set up pilots to give it a try. But in our experience, few know how to accurately assess their current positions or track their progress. Nor do they know what to change, or by how much, to improve the organization’s agility. Some have decided to count the number of agile teams that are up and running. Others report the number of people that have been trained in agile techniques. Only a handful measure the impact of agility on cash flows and shareholder value. (Of course, some agile fanatics condemn even measuring shareholder value, which is ridiculous. Just because shareholder value isn’t all that matters doesn’t mean it shouldn’t matter at all.)

Five kinds of metrics

Source: Adapted from the W. K. Kellogg Foundation Logic Model Development Guide, https://

The problem here is easily stated: there are no simple metrics that every company can use to assess its current agility or its progress toward greater agility. Instead, companies must develop their own customized indicators, testing—in good agile fashion—the relationships among the system’s major components, including inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and purposes (figure 3-3). So let’s begin by understanding those components:

- Purposes are the ultimate missions and ambitions of an agile enterprise. They are the long-term cumulative effects of an agile business system, such as Warby Parker’s ambition to lead the way for socially conscious businesses.

- Outcomes are the shorter-term changes and benefits that are achieved by agile activities and outputs, typically in one to three years. They include results such as changes in market share, revenue, shareholder value, profitability, customer buying behaviors, and team productivity.

- Outputs are the direct, immediate results of work. Common examples of agile outputs include higher quality products and services, shorter decisions, faster development cycles and time to market, and increased team productivity and morale. Are parts of the company not operating in agile teams nonetheless embracing agile values and accelerating change? Is the operating model enhancing agility rather than undermining it? Is the entire system collaborating more effectively? You can’t take outputs to the bank, but you can use them to determine whether activities are producing results that should lead to positive outcomes.

- Activities are the actions and processes that generate outputs. They include the actions of senior executives, agile teams, operations, and support and control functions. Are senior leaders using agile practices in their own work? Are they trusting and empowering people? Are they creating a culture that focuses obsessively on customers and adapts quickly to customers’ changing needs? Are the most talented and innovative people working on agile teams? Do the teams adhere consistently to agile values, principles, and practices? Are agile teams deployed in every area where they should be deployed? Are planning, budgeting, and resource allocation processes frequent and flexible enough to quickly shift resources to the company’s highest priorities?

- Inputs are the resources available to help create results. They include financial resources, the quantity and quality of agile experts, organizational structures, software tools, and technology architectures. What is the company’s level of experience with agile methods? What are the leaders’ mindsets and cultural norms? What are the company’s technology capabilities? Industry conditions are another key input: businesses that are particularly turbulent, such as technology, medical products, and retail, require more adaptive innovation than industries such as basic materials or the public sector. Strategic priorities are important as well. For instance, strategies that focus on cost leadership and scale require less agility than strategies focusing on innovation.

Together, these components create the agile business system. Doing agile right means skillfully combining them to perpetually pursue the company’s purposes, even in volatile and unpredictable conditions. Measuring agile requires developing metrics in each area.

We realize that all this may sound a little complicated. In reality, it’s just a way of organizing, visualizing, and helping you address existing complexities in ways that make them more manageable. To improve results, you need to understand where results come from and then improve the processes that cause them. The trick is learning to analyze dynamic systems in just enough detail to be insightful, without being overwhelming—finding balance, in short, and relying once again on the minimum viable solution.

An example may help. One of our retail clients was excited about the growing number of agile teams in its organization and a corresponding increase in revenue growth. But when the people there analyzed what was going on in terms of the various elements, they found some surprises. Revenues (an important outcome) were growing because industry growth was accelerating. But the company’s share of that growth (a more important outcome) was declining. Its existing core customers were as loyal as ever, but it was failing to attract the large and rapidly growing segment of next-generation shoppers. Those shoppers were not impressed by traditional forms of marketing or merchandising. They wanted faster and more reliable online deliveries. They wanted an in-store shopping experience that focused less on brands and more on solutions, such as more natural forms of skin care (outputs). There was an agile supply-chain team, but it concentrated on boosting the efficiency of traditional warehouses rather than improving both cost and speed by offering better options for shoppers to buy online and immediately pick up orders in stores (activities). There were no agile teams focused on buying the right brands, on developing the right displays, or on providing the best service experiences (more activities) for those shoppers. Worse yet, the teams had no members who represented, or even understood, the needs of the next generation (inputs). Once these cause-and-effect relationships were understood, agile teams pounced on them, improving inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and purposes.

Use Agile Methods to Determine How Agile to Be

By now, it should be clear why the chapter heading—“How Agile Do You Want to Be?”—was a trick question. At the beginning of an agile journey, it is nearly impossible to predict the answer. Predicting, commanding, and controlling is a hazardous approach to any innovation but especially to the design and development of a new business system. Ironically, senior executives who expect hundreds or thousands of agile teams to follow agile principles and practices sometimes revert instinctively to bureaucratic methods to envision, develop, and implement the new system. There’s an old saying, dubiously attributed to Albert Einstein, that we cannot solve problems with the same level of thinking that created them. Nevertheless, that is exactly how too many executives approach agile transformations. The missteps take many forms:

- Instead of demonstrating intellectual humility and admitting that the guiding vision is a working prototype that will adapt with experience, leaders attempt to maximize the motivation for change by pretending to have all the answers. They impose inflexible organizational structures. They burn the boats to quell any questions about commitment.

- Instead of recognizing front-line employees as leadership’s most important customers—the people who should collaborate on the innovation process and must ultimately make the system work—executives plot in secret war rooms and unveil the changes through public press releases.

- Instead of viewing feedback from the most experienced employees as valuable opportunities for improvement, leaders regard their opinions as criticisms from recalcitrant resisters who must be fixed or fired.

- Instead of responding to change, program management offices build complex Gantt charts with bright red dots to flag people who deviate from plans.

The value of the metrics above is their ability to focus corrective actions on true constraints. There is always at least one constraint to further progress, but there are usually fewer constraints than most people imagine. Focusing on fixing problems that are not constraints will not improve throughput and is often a waste of time, money, and energy. This is why the rush to reorganize is always less useful than leaders expect. It is usually a cover for other problems, and it typically creates more trauma than value.

Most often, restructuring is only a euphemism for major layoffs. Have you ever wondered how and why companies bounce from decentralization to centralization and back again, each time announcing layoffs to reduce costs? Or why they pursue other sorts of organizational back-and-forthing, such as changing from functional organizations to product organizations to matrix organizations, and around again? How can every change drive more cost reduction? The reason, typically, is that the executive team sets a cost quota first and only then designs an organization structure to hit it, leaving operators to deal with the consequences. Agile transitions may eventually lead to organizational changes, even continuous ones. But organization structures are almost never the primary constraint, and companies seldom require (or benefit from) immediate wholesale layoffs.

Agile itself offers so many ways to advance an agile transition with greater value and lower cost. Focus the fixes on the real bottlenecks. Get the leadership team to behave like an agile team. Clarify a common ambition. Not enough? Stop activities that customers don’t want and teams can’t deliver. Replace ineffective innovation groups with agile teams. Still not enough? Shift planning and budgeting to simpler processes at shorter intervals. Focus support and control functions on changing their business processes to better satisfy their internal customers. If the system is still unbalanced, provide more frequent feedback on performance. If these simpler solutions work, you may be able to pursue continuous improvements while postponing or avoiding some of the most expensive and painful solutions.

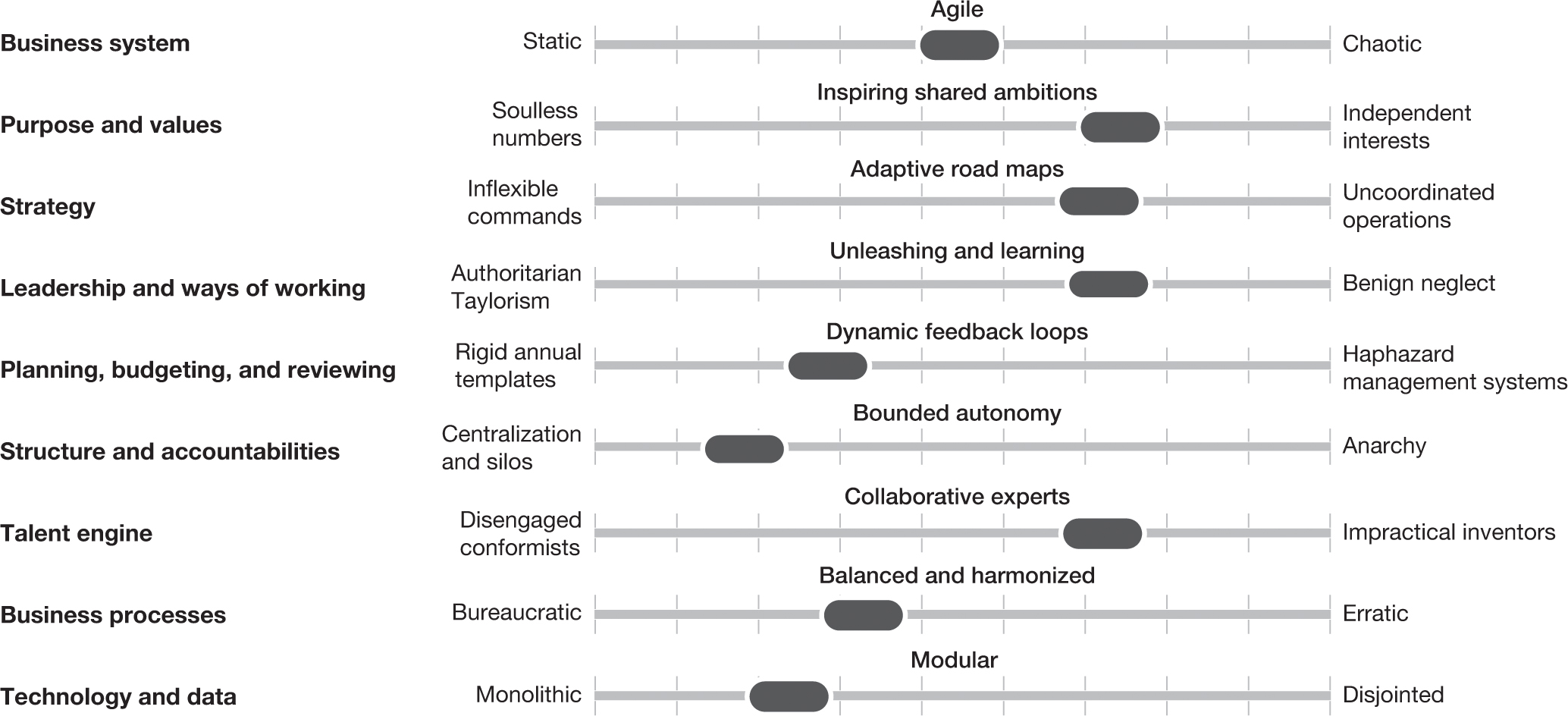

Change levers such as these essentially become the backlog of the agile leadership team. The leadership team is developing a new, highly innovative agile system, and these are the features that will ultimately come together to make the system work. Like any other agile team, the leadership team prioritizes, sequences, and harmonizes these activities to create the greatest value at the lowest cost. Members work together as a multidisciplinary group to create the system, break through impediments, and pivot as unexpected results develop. We think of the process as much like that of a skilled music mixing engineer, part artist and part scientist. If the treble is too harsh but is very hard to change, you tame it by turning up the base. You don’t change more than you need to, since that creates other problems that will then require fixes that will require additional fixes (figure 3-4; see appendix B for definitions).

All of these levers can be valuable when applied to the right problems, in the right sequence, in the right ways. We cannot detail all of the possibilities in this book, but we will discuss how to use several of the most popular change management techniques in chapters 4 through 8.

Balancing the agile enterprise operating model

Nearly twenty years before the agile manifesto appeared, a young Mark Allen was discovering the manifesto’s principles and practices for himself. His purpose was to win the Ironman World Championship. But achieving that purpose required him to hit a moving target. The first winner of the Ironman, in 1978, completed the course in 11:46:58. By February of 1982, when Allen tried to train by copying the results of leading competitors, the winner finished in 9:19:41, and the man in second place finished in 9:36:57. Benchmarking was not only producing extreme physical and mental exhaustion, it was also limiting Allen’s potential. When he won his first Ironman Championship in 1989, he finished in 8:09:14 to achieve his goal.12 That’s more than three and a half hours faster than the pioneers. Allen learned to train by setting a challenging but sustainable pace. He was patient, and he took a long-term perspective. As he exercised at his optimal pace, his performance steadily improved.13

Senior executives could choose worse analogies than imagining themselves and their organizations as triathletes in training. The maximum aerobic heart rate is the organization’s sustainable pace of change. Instead of tools and techniques such as strength training or nutrition improvements to break through performance plateaus, there are leadership behaviors, cultural norms, planning and funding systems, organization structures, people development, business processes, and technology. We’ll discuss how to prioritize, sequence, and implement these techniques in the following chapters.

FIVE KEY TAKEAWAYS

- More agile is not always better agile. There is an optimal range of agility for every business and for every activity within a business.

- It is nearly impossible to predict the right range at the beginning of an agile transition. At that point, what you are trying to develop and how you should develop it are not just unknown, they are unknowable. Too many variables are changing too rapidly and too randomly. Rarely will bureaucratic approaches succeed in such conditions. You must develop and implement the agile business system as a perpetual agile innovation program—testing, learning, and continually adapting as you would on any other agile team.

- Effective agile programs adapt to empirical feedback about inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and purposes. Few organizations currently have sufficient data to assess their present level of agility or their progress in improving it.

- Identifying and quantifying the potential benefits and costs of creating an agile business system is difficult but well worth the effort. Chances are high that the estimates will be inaccurate. That’s OK. They will be sufficient to answer many different questions, such as how much value is at stake and how much investment of time and financial resources is worthwhile.

- Use agile methods to manage agile transitions. Imagine yourself and your organization as triathletes in training. Set a challenging but sustainable pace. Be patient, and take a long-term perspective. As you reach performance plateaus, learn to deploy a wide range of tools and techniques to break through impediments and shift performance to the next level.