MEETING PLACE OF NORTH AND SOUTH

French’s early years in Washington were full of firsts. Mingling with people from around the country, working to expand the national reach of his party, seeing the South and plantation slavery: all of it was new, and its impact was mixed.1 On the one hand, he felt the bonds of Union as never before. On the other hand, he saw firsthand how fragile those bonds could be. Such was the paradox of political life at the national center: sectional differences were never as apparent as when Northerners, Southerners, and Westerners lived, worked, and played side by side.

Party loyalties sometimes bridged such divides, particularly the divide over slavery. When it came to the South’s “peculiar institution,” many a Northern Democrat like French was more than willing to appease Southern allies for the sake of the Union, their party, and their careers; the South reigned supreme in Washington in more ways than one. Such negotiations were part of the business of Congress. There—as nowhere else—French saw the working reality of the complex shifting balance of section and party that kept the Union as one.2

French’s Congress was a sprawling mix of men. Spawned by the rise of the Jacksonian “common man” and all that came with it, a wide range of people found their way into Congress, many of them figures of local prominence who served a term and then went home, sometimes vanishing from public life and even from the public record, often without a single portrait or photograph left behind. They are literally faceless names long gone. Scene-stealers like Henry Clay make it easy to forget the mass majority that profoundly shaped the human reality of the antebellum Congress.3

Given the brisk turnover, both houses were filled with a shifting cast of freshmen, particularly the House with its two-year terms; roughly half of every House was new.4 Regardless of their talents, these men mattered. They registered their opinions, defended the rights and interests of their constituents, supported their party, and countered their foes. Some of them threw an occasional punch. They were a center of gravity in Congress, an anchoring reality beneath the highfliers, a shaping influence on the texture and tone of congressional proceedings, and, through sheer force of numbers, the ultimate arbiters of what got done. It is impossible to fully understand the antebellum Congress without acknowledging their presence and influence.

Photographs are a good starting point; these men were part of the first generation to be captured on film. To French, history itself was like a photograph. A good historian should produce “a daguerreotype of the times he writes about,” he thought, preserving on paper realities great and small—the “minutia of existence.”5 Photographs capture some of this minutia, revealing very real people in the clothing, postures, and attitudes of a very different time.

Yet photographs can be deceiving; they show how congressmen wanted to appear. Taken collectively, they form a parade of self-importance, jaws set, faces unsmiling, dressed in black almost to a man, with starched white collars and cravats tied at the neck. A few strike a Napoleonic pose, one hand thrust in their vest. Many try for grim dignity and achieve it. Some have their life experiences etched on their faces. Others show a flash of the charisma that won them office. A few are simply homely. (According to acquaintances, Globe editor Francis P. Blair’s charms far outweighed his looks.)6 They all convey a certain congressional gravitas, forward-looking, farseeing, serious of purpose: the “National Statesman” that each wanted to be.

So much for the image of the antebellum congressman. What of the reality? Demographics help to fill this gap. Collect and analyze broad sweeps of data and you find that between 1830 and 1860, the average member of both houses was a college-educated lawyer in his forties with experience in public office. In the House, roughly half the members fit this description; in the Senate, significantly more.7

A composite photograph of the members of the Thirty-sixth Senate (1859–61) from the work of the famed photographer Mathew Brady (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

There aren’t many surprises here. But demographics can be deceptive; they tend to sacrifice gritty human realities in favor of assembled portraits, and when studying past peoples whose lives and habits are dramatically different from our own, minutiae matter. For example, take John B. Dawson (D-LA). Forty-three when he entered the House in 1841, he was a college-educated planter and newspaper publisher from a well-to-do family with an unsuccessful run for governor, fourteen years as a parish judge, and two years of state legislative experience; he served two terms in Congress. Demographically speaking, Dawson is the virtual embodiment of the typical representative. But look for him in Congress and you find a man who routinely wore both a bowie knife and a pistol, and wasn’t shy about using them in the House chamber, threatening to slash one man’s throat and cocking his pistol at another, among his many moments of congressional glory.8 Dawson—the hands-down winner of the Frequent Weapon Wielder award—is a reminder that tidy demographics can mask messy realities.

Look beneath that mask and you can see it: the mix of men in the antebellum Congress. In addition to sons of privilege who attended Ivy League schools, you see men who were schooled at local academies and colleges, as well as men with catch-as-catch-can educations with little more than a few years at the local “common” school, like 98 percent of all white American men.9 French’s hodgepodge education was typical of many; he bounced from ill-equipped tutors (his father’s law clerks), to the local common school, to a “commoner, if possible” local academy (“taught by a numbskull named Johnson”), to his preoccupied uncle Revevend Francis Brown, and ultimately to an academy in Maine, picking up some grammar here, some ancient history there, a splash of Latin someplace else.10 Education was patchy and erratic in early America, ranging from the systematic order of New England to some virtually unschooled portions of the South and West.11 Some virtually unschooled men found their way into Congress.

So did men who worked with their hands before entering politics, like the wagon maker Charles Bodle (J-NY), the gunsmith Ratliff Boon (J-IN), and the iron furnace operator Martin Beaty (AJ-KY). Statistically speaking, there weren’t many such congressmen, and they’re often hard to spot in demographic studies, which tend to lump people into broad bucket categories: farmers, lawyers, merchants.12 But they were there. So were growing ranks of newspapermen. Include the many men like French who served stints as editors in their youth, and the congressional contingent of newsmen is yet more striking.13

Even the teeming multitude of lawyers holds surprises. While there were accomplished scholars such as Senator Rufus Choate (W-MA)—“he knew everything,” French marveled—there were far more men who fell into the law as the path of least resistance. Legal education requirements collapsed amid the democratic upsurges of Jacksonian America; by 1851, four states had no educational requirements at all, simply declaring that any citizen of good moral character with a minimal amount of study could be admitted to practice.14 For an ambitious young man searching for a livelihood with some prestige, lawyering was the answer, particularly if he had political ambitions; given the vast number of lawyer-politicians, a law career was a virtual bid for political power. The 1830s was the first decade in which at least 60 percent of new House members were lawyers; in the Twenty-third Congress alone—French’s first—69 percent of the House were lawyers, as were 83 percent of the Senate.15 Of the fifteen men in French’s boardinghouse, only one wasn’t a lawyer. He was a newspaper editor: Isaac Hill. “He is a bitter enemy to the gentlemen of the bar and often abuses them very unreasonably,” French noted, adding wryly, “Every gentleman who boards at this house, except him, is a lawyer.”16 Clearly, Hill lived something of an uphill life.

For every Choate in Congress there was a ream of less-educated and sometimes less-polished members from a wide range of backgrounds—men like Senator Thomas Morris (J-OH), an Indian fighter, store clerk, and lawyer with only a few months of common schooling. Morris sprinkled his speeches with verses from the Bible, one of the few books in his childhood home. Like many of his congressional colleagues, he went from humble beginnings to the practice of law, to his state legislature, to Congress.17

Highborn and not-so-highborn, educated and not-so-educated, gruff and crude, sophisticated and worldly: increasingly in the 1830s and beyond, all of these men found their way into political office, broadening their horizons through the national power networks of their party and in some cases finding their way into Congress. The nation’s political elite was more diverse than facts and figures let on.

A CITY OF EXTREMES

Of course the city of Washington was even more diverse. In fact, its sectional diversity was its hallmark, and people had high hopes that it would unify the nation. The “social collisions” of living in Washington would “erode sectional prejudices,” enthused one writer, “and the East and West, the South and North, thus brought into closer intimacy, become cemented by more enduring ties.”18 Even regional accents seemed likely to fade. As the linguist George P. Marsh (W-VT) put it, “Many a Northern member of Congress goes to Washington a dactyl or a trochee, and comes home an amphibrach or an iambus.”19 Bringing together peoples and customs from throughout the nation, Washington was a city of cultural federalism.20

It was also a city of extremes. In part, this was a product of drunkenness. Much like the Capitol, Washington was awash in alcohol.21 In 1830 alone, the city granted almost two hundred liquor licenses.22 French saw liquor everywhere he looked. There were saloons on almost every corner, stinking of “tobacco smoke[,] bad cabbage & unmentionable mixtures of villainous smells.”23 Porter houses, hotel bars, dram shops, and groceries: they served liquor too, the latter two in handy gulp-sized portions. (The grocery near the Capitol did a particularly brisk business.)24 Even the lobby of the National Theater seemed like little more than a drinking hole. “If Heaven should be located here,” French thought, “there would certainly be a grog shop in one corner!” Everything in Washington seemed “contaminated by haunts of dissipation—even the Capitol itself has not escaped.”25

French’s father had feared as much when his son headed south. “You are now stationed in a land of trials & temptations beyond your [vaunted] experience,” he warned not long after his son arrived in Washington. “Theatres, Balls, gambling tables, riots … & unlawful assemblies are all before you.” Knowing full well his son’s rebellious streak, the elder French could only pray: “God grant that your choice shall obtain the smiles of an approving conscience.”26

For the most part, French’s conscience remained clear; a wavering but enthusiastic temperance supporter, he wasn’t much of a drinker. But some people let loose in Washington in ways that they didn’t dare back home. The whirl of diversity, the city’s notorious “floating population” of residents who came and went with Congress, the many men who left their wives and families back home: the “bachelor-life” of Washington “was not conducive to moral restraint,” noted an observer with marked understatement. Even staid Northerners sometimes went to extremes.27 “Many of our best men are … giving a loose rein to their ambition & their appetites,” worried Robert McClelland (D-MI) in a letter filled with misbehaving Northerners.28 Amasa Dana’s (D-NY) friends despaired when he befriended Felix Grundy McConnell (D-AL), a hard-drinking, “all-round, all-night man about town.” McConnell liked to swagger into saloons and invite everyone “‘to come up and licker.’” (French liked him fine when he was sober, but refused to commit McConnell’s witty “vulgarisms” to paper.)29 Once, at a party, thoroughly soused and with a woman on each arm, McConnell teetered up to President James K. Polk and toasted him, insisting that Polk drain his glass in a gulp, calling out, “No heel taps, Jimmy.” With McConnell by his side, Dana transformed from “a sober, steady, modest & sedate man … into a perfect rake.”30 Franklin Pierce didn’t fare much better. He hit an alcoholic low in 1836 when he and two drinking buddies, Edward Hannegan (D-IN) and Henry Wise (W-VA)—the three of them a case study in national diversity—got drunk and caused a ruckus at a theater when Hannegan got into a fistfight and pulled a gun; the rumble nearly sparked a duel.31

Drunken congressmen were the stuff of legend; newly arrived members looked for each session’s hard drinkers. “Gov. [John] Gayle [W-AL] and a man by the name of [John] Jameson [D-MO] … are the only members I have seen drunk,” David Outlaw (W-NC) reported in 1848 within his first months in office, the word only revealing his expectations.32 Diaries and letters describe men too drunk to speak clearly, too drunk to leave their lodgings, even too drunk to stand; they matter-of-factly note that one or another congressman is out on a drinking bout, called a “breeze” or a “spree.”33 In 1841, French saw a remarkable before-and-after performance by Thomas Marshall (W-KY), nephew of the renowned Chief Justice John Marshall and a self-described member of the “spreeing gentry.”34 On August 23, Marshall—“for a rarity, sober,” French noted—gave an eloquent speech that “enraptured” everyone, including the not easily impressed John Quincy Adams (W-MA), who praised its “beautiful flights of fancy.” Two days later, Marshall gave a ranting, raving speech while “three sheets in the wind,” forcing his way onto the floor, ignoring calls to order, and draping himself all over his desk, at one point leaning so far back that he was virtually lying on it. French considered it “a most disgusting exhibition.”35 (The Globe said only that Marshall “further continued” the debate.)36

Some men were surprisingly functional when boozy, even chairing the House, as did George Dromgoole (D-VA) in 1840. (“Drunk in the chair,” Adams observed matter-of-factly.)37 Others became master orators under the influence. Some of Senator Louis Wigfall’s (D-TX) most stingingly bitter and effective speeches were supposedly a product of the Hole in the Wall.38 Even the overindulgent Thomas Marshall had his moments when sloshed; Adams summed up his “peculiar style of eloquence” as “alcohol evaporating in elegant language.”39

But other men were overcome. James McDougall (D-CA) became a staggering drunk in Washington, falling off his horse on Pennsylvania Avenue, even lying in the gutter. “The temptations of the Capital were too strong for him,” a friend noted.40 Pierce’s drinking buddy Edward Hannegan suffered the same fate for much the same reason.41 A few men paid the ultimate price for their sins. In 1834, James Blair (J-SC) committed suicide due to drink, shooting himself in a state of sodden despair. Blair was a man “of sterling good sense, and of brilliant parts,” noted Adams, but “the single vice of intemperance … bloated his body to a mountain, prostrated his intellect, and vitiated his temper to madness.” Blair once drunkenly fired a pistol at an actress on a Washington stage; he carried a loaded gun to the House every day. Adams thought the “chances … quite equal that he should have shot almost any other man than himself.”42 Most shocking of all was the death of Felix McConnell, who butchered himself with a pocketknife in 1846. According to Polk, a shaky and pale McConnell, probably “just recovered from a fit of intoxication,” came to the White House, borrowed one hundred dollars, dallied at a bar, loaned some money to the barkeep, retired to his room, and killed himself.43 If a congressman was “at all inclined to dissipation,” observed one writer, “an easy and pleasant road is opened to him; and not a few yield to the temptation.”44

Formal congressional privileges sometimes made matters worse. According to Article 1, Section 6 of the Constitution, congressmen were protected from arrest while attending Congress. The fine art of flaunting this privilege has a storied history and it started early.45 According to French, in 1838, when police stopped the “Honorable” John Brodhead (D-NY) from picking flowers on the Capitol grounds, Brodhead replied, “I am a member of Congress, & I’ll let you know I shall do just what I please,” proving his point by grabbing clumps of flowers and “strewing them about.”46

This isn’t to say that all congressmen were boozed up rowdies or that all socializing was a back-slapping, booze-drinking bonanza. There were genteel receptions, parties, dinners, “hops,” and fancy balls galore.47 French and Bess attended and hosted many, though even tame events could have a risqué undertow; one congressman noted a string of colleagues cheating on their wives.48 Nor were the city’s freedoms restricted to partying. The New York writer Anne Lynch loved the “intellectual superiority” born of the city’s “delightful freedom,” particularly for women. Washington wasn’t “hedged round by so many conventionalities,” she thought.49

All in all, Washington’s diversity was a mixed bag, forging cross-regional friendships even as it fostered the city’s turbulent spirit. On both counts, it influenced not only the Washington community but also the community of Congress.50 One reporter said so outright: “The disagreeable, shocking scenes which are so often witnessed in both Houses of Congress, would perhaps not occur, if there were an independent and sufficiently consequential society in Washington, capable of punishing offenders against the proprieties of life.”51 An unfettered Washington meant an unfettered Congress. Washington’s gloriously freeing diversity set the stage for congressional violence.

LIVING IN SLAVE-LAND

French did some moderate dissipating. During his first spring in Washington, he went to the city’s wildly popular horse races and loved it. The excitement, the fighting, the gambling, the drinking: French had never seen anything like it. “[V]ery many honorable members of Congress were—not exactly sober,” he reported to his half sister Harriette, swearing that he “drank nothing, not even a glass of water.”52 Within a year or two, he had learned to play billiards (or as he put it in his diary, “have learned to play billiards!”).53 But the appeal of cockfighting was beyond him: “pah. It almost made me sick.”54

Horse racing, gambling, and cockfighting: some of Washington’s most popular pastimes had a distinctly Southern flavor. In fact, national city that it was, Washington was Southern at its core. As one Ohio congressman attested, the city’s “fixed population” was “intensely southern.”55 In 1830, roughly 60 percent of its permanent white residents were from Southern states or had strong Southern ties, and about a third of the city’s residents were black; the fact that more than half of these black residents were free made Washington a true border-state town.56 Even the city’s town houses, with their back-lot outbuildings for housework, mirrored the layout of plantations.57 In more ways than one, the South reigned supreme in Washington.

Of course, the most obviously Southern aspect of Washington was the ubiquitous presence of slavery. The auction blocks and slave pens, one of them clearly visible from the Capitol’s windows; the cuffed slave gangs; the brutality that infused a slave regime: although Washington wasn’t a central hub of the slave trade, slavery’s grim realities struck Northerners in the face when they first arrived.58 (“Here I am in slave-land again,” reported the Massachusetts Free-Soiler Horace Mann upon arriving in Washington in 1852.)59 Not long after his arrival, Joshua Giddings (W-OH) was stunned to see a slave gang of sixty-five shackled men, women, and children being marched down the street.60

French was stunned to be living with slaves; New Hampshire was overwhelmingly white in 1830, with 602 free black citizens and 5 enslaved people out of a total population of 269,328.61 I have “a servant to wait on me whenever I call,” he wrote wonderingly to Bess during his first days in his boardinghouse. “There are about a dozen or fifteen servants about the house, all negro slaves.”62

Not all of New England was as free of slavery as New Hampshire, where it had never really taken hold; for a time, the nation’s “free states” weren’t entirely free. Slavery was scattered throughout New England in small numbers, and it shaped the region dramatically, enabling it to shift from subsistence farming to a market economy.63 It was also entrenched. Emancipation in most Northern states didn’t come easily; it was a complex process that took decades and introduced new complications; for some Northern whites, disapproving of slavery was one thing and living among free blacks was quite another.64 Slavery and race were very real problems in New England, and New Englanders like French arrived in Washington with their home-born prejudices intact.

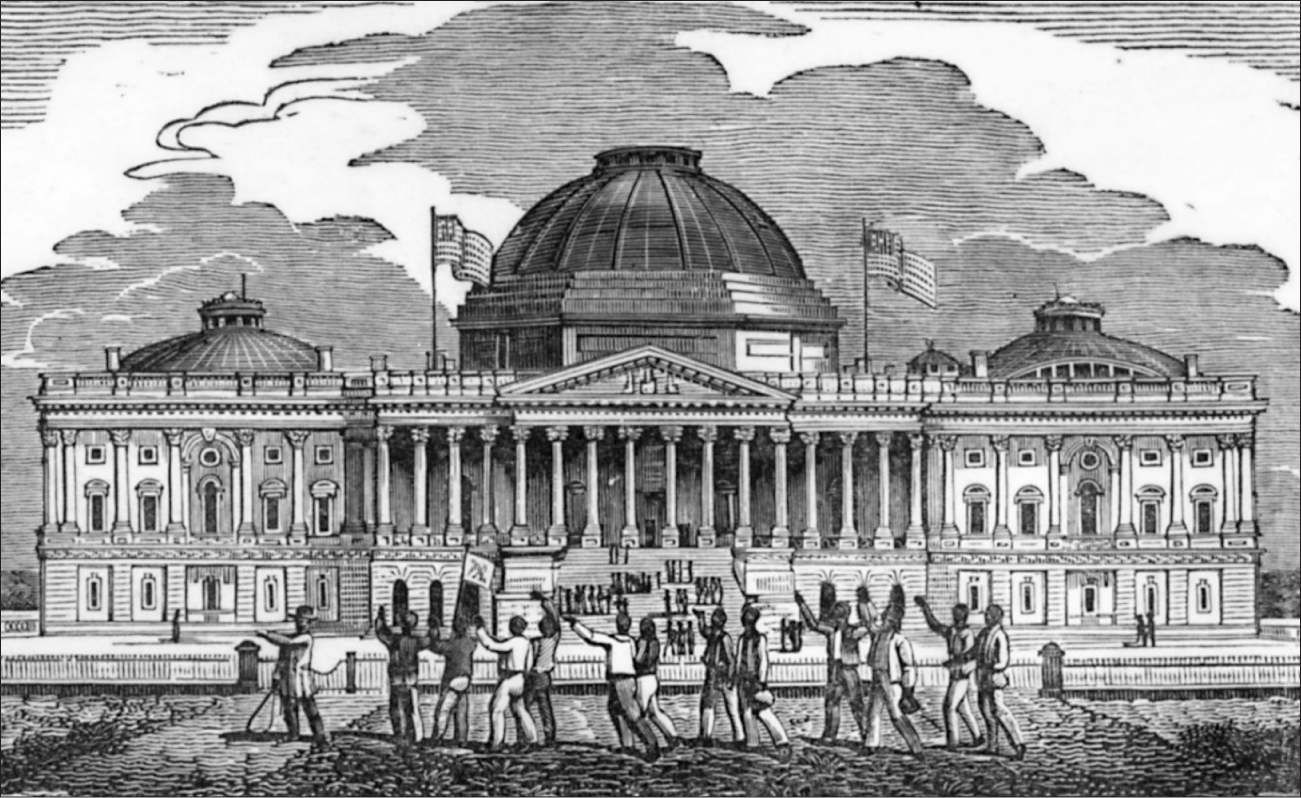

Detail from an American Anti-Slavery Society broadside showing chained slaves in front of the U.S. Capitol (The Home of the Oppressed by William S. Dorr, 1836. Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

But Southern plantation slavery was an entirely different thing. Many Northern congressmen had never seen a plantation or talked slavery with slaveholders. Curious Northerners sought out such encounters, sometimes at the encouragement of Southerners, who were all too eager to free their Northern allies of their “temporary … prejudices,” as one Southerner put it.65 The abolitionist Harriet Martineau experienced this Southern charm campaign firsthand; on her first day in Washington she was visited by several Southern senators and their wives, who pledged their services and invited her to their homes to see plantation slavery for herself.66

French’s friend and fellow New Hampshirite John Parker Hale (D-NH) couldn’t wait to talk slavery with slaveholders. “I have had an opportunity which I have long wanted, viz. a full unreserved & frank conversation with a Southerner, an intelligent & gentlemanly man, on the subject of Slavery,” he told his wife during his first weeks in Congress in 1844. The man was “not only willing, but I thought quite as willing to answer as I was to ask questions.” Two more conversations revealed something that would shock most Northerners, Hale thought: white Southerners were “hard-working people.” One South Carolina congressman even made his own hoe handles.67 Four years later, Hale advanced his slavery schooling by spending a weekend with four wealthy planters at a nearby plantation, discussing slavery.68

Many Northerners made similar visits.69 French did. In 1851, he and his family visited the Maryland plantation of his fellow Mason Michael Carroll, and French was pleasantly surprised.70 Carroll’s slaves seemed well-off; the house slaves were “dressed better than N.[ew] H.[ampshire] Farmers’ wives & daughters.” And Carroll seemed to care about them, almost sobbing over a beloved slave’s recent death. French’s diary account virtually oozes relief, suggesting that as dedicated a Democrat as he was, he’d had his doubts about plantation slavery. His visit eased his conscience and made him roaring mad at abolitionists who were threatening the Union. God sanctioned slavery, he insisted in his diary a few days later: “the old Testament abounds with evidence.” And abolitionists were fanatical Union-busting blasphemers with baseless claims; to prove his point, he attached a newspaper clipping about recent New Hampshire antislavery resolutions that seemed to violate “in spirit, the Holy Word of God.”71 When Carroll died a month later, French’s obituary sang his praises as a “good, generous, and noble-hearted master” and condemned Northern “fanaticism.”72 His plantation visit had had an impact.

But so did other visits. Witness French’s tangled trajectory: As a Northern Democrat, he had come to Washington as a self-described “ultra” on the issue of slavery, so firmly convinced that only slaveholding states had the right to act on it that he didn’t think that people in free states had even the right to petition against it.73 A conversation with the Ohio abolitionist Joshua Giddings in 1849—a mere two years before his plantation visit—changed his mind. After hearing Giddings argue in the House that slaves weren’t property, French had been so intrigued that he went to Giddings’s boardinghouse to chat about it. He came home vowing to help abolish slavery in the District of Columbia.74 Two years later, French would be declaring slavery God-sanctioned after visiting Carroll’s plantation. The following year he devoted himself to promoting Franklin Pierce’s South- and slavery-friendly presidential bid. Yet not quite a month after Pierce’s nomination, French wrote a poem honoring Giddings for a speech condemning Pierce’s proslavery views.75 French wavered on slavery, and he wasn’t alone; for many Northerners, living in Washington put their politics to the test.

“A NEW HAMPSHIRE BOY”

For a time, the bonds of party overcame such sectional fluctuations—or at least, they outweighed them, particularly in Washington, where many people experienced their party as a national organization for the first time. Fragile though they were, political parties of the 1830s forged vital national ties. A far cry from today’s top-down enterprises, they were essentially national leagues of local organizations. Cities and towns had party clubs and committees; county, district, and state organizations fostered and corralled those local efforts; and politicians in Washington helped as best they could, coaching and guiding more than anything else.76 Well into the 1840s there was no central party management and no clear chain of command; party organization stemmed from local organizers like Isaac Hill. Even national party conventions, which had their start in the 1830s, were initially centered on creating party unity, gathering together a far-flung group of allies to hash things out.77 National party politicking was much like the Union: decentralized, localized, and bound by ties of sentiment more than structure.

Thus the novelty of politicking in Washington. Local politicos like French suddenly found themselves banging the party drum with allies from near and far, particularly in Congress, the national center of partisan “slang-whanging.”78 French was a noteworthy cog in the congressional slang-whanging machine. He was a congressional correspondent for Democratic newspapers in New Hampshire, Washington, and Chicago. (Isaac Hill’s brother Horatio co-owned the Chicago Democrat.)79 As an active member of the city’s Jackson Democratic Association and ultimately its president, French corresponded with sister clubs around the country, collecting information and spreading the party line. He helped stage massive celebrations and lavish banquets with guest lists of hundreds of prominent Democrats from around the country and national press coverage that preached the glories of their visibly national party to a widespread audience. In Washington, French forged national party ties.

For much of the 1830s, Whig and Democratic party ties alike centered on the iconic figure of Andrew Jackson. The early Whig Party was a conglomerate of interests bound together by their hatred of “King Andrew’s” polarizing politics.80 The “wiggies” were an “unholy league” of “ites” (“Bank-ites,” “Tariff-ites”) formed “of the odds & ends of disappointed factions,” French thought. They were a blend of “Abolition, Antimasonry, old Federalism & humbug, mingled with drunkenness and dissipation,” and little else.81

For the Democrats, of course, love of Jackson knew no bounds. French virtually genuflected at the mention of his name. Even in his diary, he gushed.82 The magic at the heart of the Democracy was the rhetorical link between Jackson and the Union; in the Democratic cosmos, they were lastingly entwined. At the events that French organized, these polestars of the party almost always led the way. Promoting Jackson would promote the Union; worshiping Jackson was worshiping the Union; national party unity would breed national unity: Jacksonian Democrats north, south, and west joined in singing one song. And French was a choirmaster, a fount of Democratic songs and poems.83

An 1852 Battle of New Orleans dinner was typical of many. The Washington Jackson Democratic Association sent invitations to Jackson’s “friends” throughout all thirty-one states, inviting them to a banquet that would bolster party bonds and Old Hickory’s beloved Union, and promote Franklin Pierce’s presidential bid in the process. The lavish gathering, attended by five hundred people, featured three hours of speechifying, a B. B. French song (“The Altar of Liberty”), and at least sixty toasts, with French—a man with a “pair of lungs admirably calculated to keep order,” according to the Baltimore Sun—repeating the toasts so that everyone could hear. (“I almost split my lungs,” he later groused.)84

So routine were such pro-Jackson fanfares that they became a standing joke. An 1828 newspaper parody caught the parade of excess perfectly. Predicting how that night’s Battle of New Orleans celebration would go (because “it can be predicted with as much certainty as the weather in an almanac”), it described an elaborate banquet featuring half an alligator, and if necessary, eaten words; a series of ridiculous toasts; and a grand triumphal song, heralded with trumpets, bagpipes, gongs, and a “Grand Shout,” followed by the song’s opening lines, “Strike the Tunjo! Blow the Hugag!”—a B. B. French song on steroids. This “famous ‘hugag and tunjo’ article” so perfectly captured the pomp and nonsense of the period’s politicking that satirists mined it for decades.85 But silly or not, such grandstanding worked: it fueled passions powerful enough to bridge sectional divides.

Yet those divides persisted, even for a devoted national party operative like French. Given his party electioneering, his decades in Washington, and his congressional career, it’s hard to imagine someone more national in perspective or Washingtonian in spirit. It becomes harder still when his endless stream of civic responsibilities is thrown into the mix. French was president of the City Council, an alderman, a co-founder of one local charity and active in several others, a trustee of the public schools and a supporter of a school for free black girls, assistant secretary for the Smithsonian Board of Regents, and a lecturer for clubs and societies all over town. As commissioner of public buildings under Presidents Franklin Pierce, Abraham Lincoln, and Andrew Johnson, he repaired bridges, watered down the dusty avenues, and oversaw the Capitol’s extension and new dome, which featured French’s name inscribed on the “Goddess of Freedom” sculpture at its top.86 As Grand Master of the District of Columbia Masons, he even laid the cornerstones of three of the city’s most iconic buildings: the Smithsonian Institution, the Washington Memorial, and the Capitol extension.87

But as dedicated a national organizer and Washingtonian as French was, he viewed the world through a New Hampshire lens. He was looking through that lens when he attended a Democratic rally in Maryland in 1840. Curious to see “how they manage political meetings in this part of the Union,” he was impressed. The speeches—given by congressmen—were just the thing to “tickle the ear & stir up the feelings of the multitude.” But the flagpole! No one from the Granite State would have settled for such a puny flagpole. New Hampshire poles stood one hundred feet high; this one was so short that if the wind hadn’t been blowing, the flag “would have trailed upon the ground!”88 (Competitive pole-raising ran rampant during electoral campaigns, adding a whole new dimension to the manly art of politics.)89 Even amid a crowd of people who were virtually—if not literally—singing his song, French was a Granite State man to the core.

In fact, he was never more a Granite State man than when he was in Washington. He praised New Hampshire in poems and toasted it at dinners. (“New Hampshire!—Before my heart shall forget thee, it must become harder than thy granite.”)90 He sang its glories in songs, as in one that he wrote for the 1849 “Festival of the Sons of New Hampshire,” a celebration of native sons living “abroad” (in foreign countries like Boston and Washington):

Our granite race are every where,

Where man can find employ;

If ever man was in the moon,

’T was a New Hampshire boy.91

He was a virtuoso of the New Hampshire non sequitur. Unexpectedly called to the podium during a St. Patrick’s Day dinner in 1843 and casting about for kinship with the Irish, he came up with this: “it was said that the Emerald Isle rested upon a bed of granite, and he himself was born in the ‘Granite State.’”92 Even in death he salutes his home state; he lies beneath a granite obelisk in Washington’s Congressional Cemetery. To say that French was proud of his birthplace (as he himself couldn’t say often enough) is a colossal understatement.93

French identified just as much with his home region. His writings are filled with references to his “Yankee ears” and “Yankee blood.” He was quick to praise Yankee ingenuity and just as quick to see the Yankee in people he liked; he thought the “very amiable” Charles Dickens looked far more like a Yankee than a Brit.94 His closest friends in Washington were from Maine and New Hampshire. And he wasn’t a lone Yankee fan; he was an active member of the New England Society of the District of Columbia, a club devoted to celebrating “the land of the Pilgrims” and promoting Yankee charity.95 His New England accent was just as steadfast; more than a decade after arriving in Washington, his Yankee twang remained so sharp that even New Englanders noted it.96 An 1849 newspaper sketch put it best: French “retains a deep and ardent love for New England, of which time does not seem, in any degree, to abate the fervency.”97

This reporter was more accurate than he knew. Because not only didn’t French’s time in Washington cool his love of New England; it intensified it. Watching New Englanders mingle with Southerners and Westerners, French gained a new understanding of what set them apart. His writings are filled with lessons learned: Yankees are industrious; Yankees are brave; Yankees can hold their own in a fight. French developed a new and stronger image of New England in Washington; in the process, he learned just how different the rest of the Union could be.98 He was experiencing in person the ultimate lesson taught by life in the nation’s capital: the Union truly was the “Glorious Whole of glorious Parts.”99

The same held true for many congressmen: being in Washington revealed and reinforced regional views. This was as true for Southerners as it was for Northerners. The presence of Northern “he-women” taught Representative David Outlaw of North Carolina just how superior Southern women were. “There is a boldness, a brazenfacedness among the Northern city women, as well as a looseness of morals which I hope may never be introduced south,” he complained to his wife, who was safely and permanently ensconced in North Carolina.100

Caricatures of the stereotypical unpolished Western congressman, starchy Northerner, and swaggering Southerner (Harper’s Weekly, April 10, 1858. Courtesy of HarpWeek)

Some Southerners found Northern men no more impressive. Back home after a term in Congress in 1841, Charles Fisher (D-NC) announced his findings in a speech. “Why is it that the condition of the people of the Southern States, is not as good as that of the people of the Northern States?” he asked. Some “among us … say it is owing to the superior sagacity, & greater industry of the people of these states over our people.” This was untrue, Fisher stated, and he had proof: “We meet them in Congress—are they sup[erio]r there?”101 The reluctance of Northern congressmen to brawl or duel was just as striking; Southern scorn of Northern cowardice was a constant.102 Here was the flip side of cross-regional bonding: familiarity could breed contempt.

In this sense, being in Congress required an internal balancing act. Congressmen were in a national institution doing the nation’s work with a national sampling of colleagues tied to national parties; but doing that work highlighted what set them apart. Although party loyalties often reigned supreme, for most congressmen, as for French, sectional preferences framed their vision of the world.

DOCILE DOUGHFACES

At no time was this balancing act more apparent than when casting votes, because every vote was a statement of priorities. Thus the creative ways in which congressmen dodged vote calls. Such personal compromises were the stuff that the Union was built on, makeshift as they might be.

Northern Democrats were notorious for this kind of dodging, largely because of the problem of slavery. When it came to that seemingly irreconcilable difference, preserving party unity and preserving the Union required dodging and weaving on all sides. Some evasive measures were more successful than others. Sweeping stratagems like gag rules that prohibited discussion of slavery petitions were stereotypically Southern; uncompromising, unapologetic, aggressive, and heavy-handed, they did more to stoke antislavery fires than to slake them.

Subtler strategies were better at smoothing the waters, and when it came to subtleties, Northern Democrats like French were virtuosos. As Northerners, some of them weren’t entirely comfortable with slavery’s morality or realities; by the 1830s, many of them viewed it as both Southern and foreign.103 They also were keenly aware of the precarious balance of power between states slave and free, so the addition of new slave states couldn’t help but give them pause. Many of them had racist fears that freed slaves would head north, as well as realistic fears that attacking slavery would destroy both the Union and their party.104 Some worried that slavery would overrun Western territories and outpace yeoman farming. Yet their support of states’ rights gave them a hands-off policy concerning slavery. For Northern Democrats, there was a brutal bargain at the heart of party membership: the rewards of party power were tied to preserving slavery. In exchange for the former, they accepted the latter. In the Democracy, as in Washington, Southerners held sway.

French’s views were typical of many Northern Democrats, a messy, shifting blend of generalization, distraction, abstraction, and denial. As he put it when pressed on the matter in 1855, he was

so much a Freesoiler as to be opposed to the addition of any more slave territory to this Union—but utterly opposed to the agitation of the question of slavery if it can be avoided, &, although abhorring slavery in the abstract, defending it to the utmost of my power so far as it is tolerated or justified by the Constitution.105

French abhorred slavery, wanted no new slave states, defended slavery, and didn’t want it discussed. His one tangled sentence exposes an internal tug-of-war felt by many Northern Democrats.

There was a word for men like French: doughface. Coined by the acerbic and eccentric Representative John Randolph of Virginia, it referred to Northerners who catered to Southern interests. As defined by Bartlett’s Dictionary of Americanisms (1848), doughface was a “contemptuous nickname, applied to the northern favorers and abettors of negro slavery.”106 The term first gained popularity after the Missouri Compromise of 1820, and it had a sting, particularly in Congress. By implication, doughfaces were servile, docile, and all-around unmanly. Working side by side with slaveholders, congressional doughfaces risked being these things in person. When they responded to proslavery blustering by backing down or making nice, they seemed to prostrate themselves before their slaveholding colleagues. In Congress, the challenges of balancing section and party could be painfully personal.

It makes perfect sense that Randolph coined this notorious slap at Northerners; he was a master of Southern swaggering. Famed for his brilliant, rambling, and sometimes drunken oratory, his razor-sharp wit, his fighting temper, and his shrill, piping voice, Randolph stalked around the House booted and spurred, riding crop in hand and hunting dogs at foot, beating men down with withering insults and tossing off duel challenges, a virtual caricature of a Southern slave lord. He has the dubious distinction of being the only person to have challenged both Henry Clay and Daniel Webster to duels, though only the Clay duel advanced to a dueling ground, with no blood shed. When Thomas Hart Benton solemnly delivered Randolph’s challenge to Webster, who was relaxing on a sofa on the outskirts of the House, Webster was nonplussed, to say the least; he read it, carefully folded it, paused, unfolded it, reread it in seeming disbelief, and wiped his brow.107 Randolph ultimately retracted the challenge.

Although the term doughface has puzzled people almost from the moment that Randolph uttered it—Doe face? Dough face?—in fact, he was referring to a children’s game involving dough masks donned to frighten people. Using the term in 1809, Randolph said that passing a nonintercourse act against Great Britain was equivalent to dressing up in a dough face to frighten people “who may blow our brains out.”108 He used the term again in 1820 during the crisis over Missouri’s admission to the Union. Speaking of Northerners who had voted with the South to admit Missouri as a slave state, Randolph mocked their “conscience, and morality, and religion,” declaring:

I knew these would give way. They were scared at their own dough faces—yes, they were scared at their own dough faces! We had them and if we had wanted three more, we could have had them; yes, and if these had failed we could have had three more.109

As appreciative as he was of Northern supporters, Randolph couldn’t stomach their seeming servility. By his logic, these men had prostrated themselves before the South out of fear of fracturing their party and perhaps the Union. Thirty years later, Walt Whitman echoed the thought in a poem titled “Song for Certain Congressmen,” later retitled “Dough-face Song”:

We are all docile dough-faces,

They knead us with the fist,

They, the dashing southern lords,

We labor as they list.110

For both Randolph and Whitman, doughfaces were cowards who had betrayed their home region.

For Northern congressmen working alongside Southerners, such blows hit hard, particularly given Northern parliamentary acrobatics aimed at sidestepping slavery; in their flagrant attempts to flee the issue—sometimes literally—Northerners looked cowardly. Some of them routinely dodged problem votes; in 1850, during voting over the controversial Fugitive Slave Act mandating that runaway slaves anywhere in the country must be returned to their masters, a pack of Northerners had a sudden urgent need to visit the congressional library. William Seward’s (W-NY) son saw them aimlessly milling about and knew enough to ask what was happening in the House.111 Their absence was duly noted—and mocked; once the bill passed, Thaddeus Stevens (W-PA) wryly suggested sending a page to the library to tell the dodgers “that they may now come back into the Hall.”112

Vote changing was another doughface dodge. For example, at the opening of Congresses between 1835 and 1843, some Northern Democrats routinely voted against a rule “gagging” discussion of slavery petitions, well aware that their constituents might object to it. Later in the session when the rule was no longer in the spotlight, these doughfaces would drift back to the “pro–Gag Rule fold”—and national party unity—for the rest of the session.113

Some Northerners were equally adept at dodging problem Southerners, fleeing the chamber rather than endangering party unity by confronting aggressively proslavery allies. After just one week in Congress, William Fessenden (W-ME) had already fled the House several times. The need to adopt rules for the session had raised talk of a gag rule, sparking a slew of Southern insults about Northern fanatics oppressing the South. Afraid of being “forced into a reply & defiance,” Fessenden and a number of other Northern Whigs left the chamber to avoid “disappointing our friends, & ruining the party.” A few times, “pushed beyond all power of human patience,” he tried to get the floor, “thanking God afterwards that I did not succeed.”114 Fessenden was afraid of being defiant to brother Whigs—striking testimony to the tangled emotions behind Northern party loyalties. “Selfish” Southern Whigs didn’t struggle that way, he grumbled; they lashed out at their Northern allies thinking only of themselves. Such selfishness was the flip side of being a doughface: being disloyal to one’s party for the sake of one’s section. “The truth is that we are cursed with a set of allies who are enough to ruin any party,” he told his father.115 Sustaining the balance of section and party was no easy thing.

Dodging, fleeing, and flip-flopping: many a new congressman was stunned by such spinelessness. Within his first two weeks in Congress, the abolitionist Joshua Giddings was shocked to find “our Northern friends so backward and delicate.”116 John Parker Hale (D-NH) said virtually the same thing during his first term.117 Even Southerners who banked on doughface votes sneered at Northern servility, stirring up sectional discord in the process. To Henry Clay, the two words dough and face with which John Randolph had “rated and taunted our Northern friends … did more injury than any two words I have ever known.”118

Antislavery advocates had more reason than most to denounce doughface treachery. Giddings declared even slaveholders more honorable. “I may be led to confide in the honor of a slave-holder,” he said during debate in 1843, “but a ‘servile doughface’ is too destitute of that article to obtain credit with me.”119 Hale found the “servility of some of the Northern democrats to Southern dictation … humiliating and disgusting to the last degree.”120 Doughfaces were “white slaves,” charged one congressmen; they suffered from “slavery of the mind,” said another.121 The only way to defeat slavery was for free-state congressmen to assume “a bolder tone, and rise above the unmanly fear of slaveholding ‘chivalry.’”122

Clearly, doughface was more than a political label in Congress. It was a personal insult that put one’s manhood on the line.123 Franklin Pierce (D-NH) felt this firsthand during an 1836 debate over slavery in the District of Columbia. To prove that abolitionism was a looming threat, Senator John C. Calhoun (N-SC) claimed that Northern Democrats routinely underplayed the number of abolitionists in their home states in the hope of soothing Southern allies. As proof, he cited a newspaper article that accused Pierce of committing that sin and branded him a doughface. Isaac Hill immediately leaped to Pierce’s defense, as did Thomas Hart Benton after a hasty consultation with Pierce, who had entered the Senate chamber as the article was being read, and blanched. Calhoun apologized to Pierce at least three times in the next few days, during debate and man-to-man. It was a good thing, too, noted John King (D-GA), for “what encouragement did such treatment afford to our friends at the North to step forth in our behalf?”124

But Calhoun’s apologies weren’t enough for Pierce. A few days later in the House, still visibly upset, he fought back. He first justified his claims about the paltry threat of New Hampshire abolitionism (by pooh-poohing the importance of antislavery petitions signed by women, among other things).125 Then he addressed the second charge. He had been called an epithet coined by “one of the ablest debaters of any age” that in the North “was understood to designate a ‘craven-spirited man.’” It was a lie to say he was a doughface, he declared, and he would physically fight anyone who dared declare it true. He didn’t want to “provoke an assault.” He had nothing against Calhoun, who had apologized. But for all other comers, Pierce hereby declared, “once for all, that if any gentleman chose to take that statement as correct, he might put Mr. P’s spirit to the test when, and where, and how he pleased.”126 By this point, Pierce was so wound up that he had to sit down. But he made his point. Accused of being a cowardly tool of slave-driving Southerners, Pierce had demonstrated his manliness by pronouncing himself willing to fight.

New Englanders got the message. John Fairfield (D-ME) proudly declared Pierce just the man to stand and fight.127 Even Whig newspapers offered grudging respect. The Connecticut Courant noted Pierce’s “gallantry, show of fight, and real spunk,” concluding, “Pretty well for New Hampshire.”128 The Democratic New Hampshire Patriot went one step further: not only was Pierce brave, but the “nullifying bravadoes” had “quailed” in response. These “southern nullies” were “the greatest cowards in the world,” the writer scoffed. Though they “bluster and talk big, yet they quail and cower when they are before a yankee that faces them in their own manner.”129 By the Patriot’s logic, Pierce had saved his reputation and asserted his manhood by acting like a Southerner.

FIGHTING MEN AND NON-COMBATANTS

The Patriot was voicing a popular notion that seemed readily apparent in the mix of men in Congress: many a Southerner or Southern-born Westerner was what French called “a hard customer.”130 They talked big and blustered. (“[B]ombastical heroics,” French called it.)131 They strutted and swaggered. They met challengers with fist-clenched or pistol-gripping or knife-wielding defiance; armed and ready, they flaunted their willingness to fight.132

Take for example the frequent weapon wielder John Dawson (D-LA). It’s hard to tell what Dawson was like in the Louisiana legislature. Maybe he had more self-control. Maybe not; this was a violent age of aggressive manhood, and Louisiana in the 1840s had some rough edges, as did Dawson, a self-described man of “malignant hatred” who had a penchant for fighting duels with the aptly named cut-and-thrust sword.133 Given his relative obscurity on the national stage, it’s also hard to tell how others judged him, though there are clues. John Quincy Adams summed him up as a “drunken bully,” and thanks to his 1842 threat to cut a colleague’s throat “from ear to ear,” he became something of a byword for bullying on the floor. Threats were sometimes met with a mocking “Are you going to cut my throat from ear to ear?”134 All in all, it’s entirely possible that Dawson was a blade-wielding charmer wherever he happened to be; when he died in 1845, even his congressional eulogists couldn’t avoid mentioning unnamed “grave faults.”135

But what’s most telling about the congressional Dawson are his literal and figurative trigger points. In one way or another, it was opposition to slavery that galled him enough to wave a weapon. His throat-cutting victim, a Whig Southerner, had been defending John Quincy Adams’s right to speak during a ruckus over antislavery petitions. The outspoken Joshua Giddings was honored by Dawsonian ire more than once. In the midst of an antislavery speech by Giddings in 1843, Dawson shoved him and threatened him with a knife. (“I take it, Mr. Speaker, that it was not an attempt to cut his throat from ear to ear,” Adams joked darkly.)136 Two years later, during another Giddings antislavery speech, in what may rank as the all-time greatest display of firepower on the floor, Dawson, clearly agitated, vowed that he would kill Giddings and cocked his pistol, bringing four armed Southern Democrats to his side, which prompted four Whigs to position themselves around Giddings, several of them armed as well. After a few minutes, most of the pistoleers sat down.137 Dawson may or may not have been a troublemaker in the Louisiana legislature, but he was one in Congress for one central reason: face-to-face attacks on slavery.

This portrait of the knife-bearing, pistol-wearing frequent fighter John Dawson of Louisiana hints at his inner demons. (Gen. the Hon. John Bennett Dawson of Wyoming Plantation, West Feliciana Parish, ca. 1844–1845, by C. R. Parker. Courtesy of Neal Auction Company)

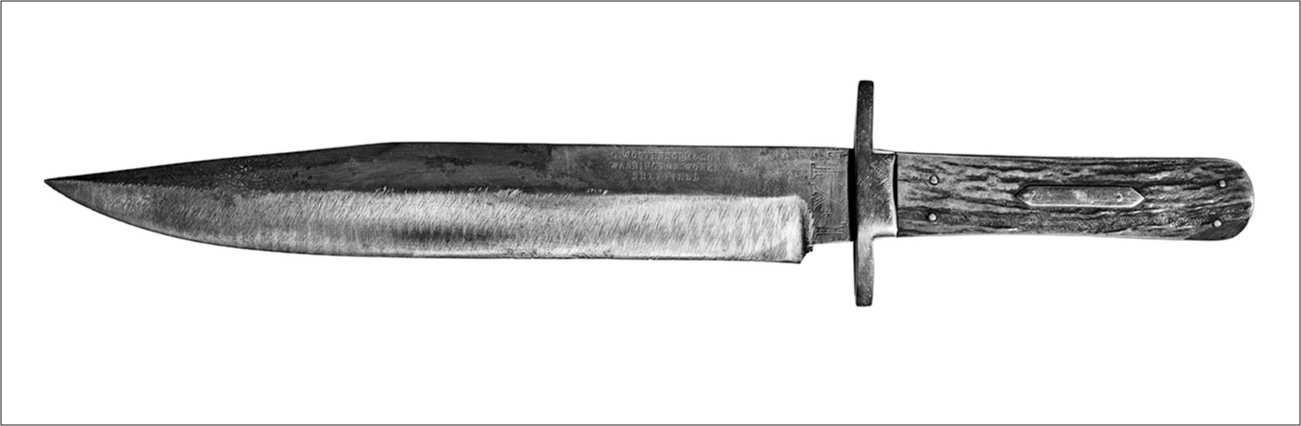

A bowie knife of the sort worn by congressmen in the 1830s (Photograph by Hugh Talman and Jaclyn Nash. Courtesy of National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

In the South, most Southerners didn’t confront open opposition to slavery in their everyday lives. Even in print it was beyond the pale; a flood of abolitionist tracts mailed south in 1835 prompted panic, mass protest rallies, vigilante violence, and bonfire burnings of sacks of mail.138 It’s not surprising then that confrontational antislavery talk in Congress was a challenge that some Southerners handled better than others; many took it as a personal affront that they felt bound to avenge. As John C. Calhoun said in 1836, there were only two ways to respond to the insults proffered in antislavery petitions: submit to them or “as a man of honor, knock the calumniator down.”139 Many slaveholders chose the path of most resistance, even on the House and Senate floors.

In part, this was a matter of custom. Such man-to-man encounters were semi-sanctioned in the South; authorities rarely intervened.140 Southerners were accustomed to mastery in more ways than one. Indeed, their lives depended on it. By definition, a slave regime was violent and imperiled; the chance of a slave revolt inspired a wary defensiveness on the part of slaveholders, making them prone to flaunt their power and quick to take violent action.141 When it came to leadership, violent men—sometimes very violent men—had a popular advantage. Robert Potter (J-NC) was elected to his state legislature after his release from jail for castrating two men he suspected of committing adultery with his wife; when he committed the crime, he was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives. William Lowndes Yancey (D-AL) was elected to the Alabama House and then the U.S. House of Representatives after killing an unarmed man by shooting him in the chest, pistol-whipping his head, and stabbing him with a sword cane.142

Appearances mattered in such a world; authority and power were contained in a man’s person as well as his property. Thus the public-minded nature of Southern violence and its notorious brutality. It was meant to impress.143 Honor culture was of a piece with this world. A man was only as honorable as others thought him to be.144 Duels were more about parading manhood and showing coolness under fire than they were about killing. Cower before a duel challenge and you were no man at all.145

Northern violence was different. This isn’t to say that Northerners couldn’t be savagely violent or that they were immune to the power of honor culture. The “Yankee code of honor,” as French called it, had its own logic and power.146 Less grounded in gunplay, it was no less centered on manhood.147 Canings were common in the North, as were ritualistic “postings”—printed insult-filled public attacks on offenders who refused to defend or take back their offensive words. After a particularly heated congressional election, two of French’s Maine friends in Congress posted each other.148 Mainers were New England’s frequent fighters, partly a product of the young state’s frontier spirit; it had achieved statehood as recently as 1820.

Yet as belligerent as Northerners could be, many were slower to fight than Southerners and quicker to call in the law. In the North, when assaults went too far or rioting erupted, authorities often imposed order. Most casualties in Northern riots were killed by authorities trying to rein people in; in contrast, Southern rioters tended to kill one another.149 Thus the Northern response to violent displays in Congress; more often than not, Northerners turned to the Speaker or chair to enforce the rules. John Quincy Adams dubbed their pleas “lamentation speeches.”150

These sectional styles of fighting bumped up against each other in Congress.151 In congressional lingo, most Northerners were “non-combatants” and many Southerners were “fighting men,” which gave them a literal fighting advantage.152 In essence, some men were willing—even eager—to back up their words with weapons, and some men weren’t, which compelled them to back away from confrontations and risk looking cowardly in the process. The British visitor Harriet Martineau thought that Northern servility was palpable in Washington. With their “too deferential air” and habitually “deprecatory walk,” New Englanders seemed to “bear in mind perpetually” that they “can not fight a duel, while other people can.”153 Southerners, in contrast, used violence as a “device of terrorism” to force compliance to their demands—and they did so with pride.154 Southerners and Westerners “would do these things now and then, and man could enact no laws that would prevent them,” declared William Wick (D-IN) in 1848 after two congressmen flipped a desk and started slugging each other. If the House formally reprimanded the combatants, “the country would laugh it to scorn—at least, all that country west of the mountains.”155 The matter ended in something of a compromise: a formal resolution that the House accept a public apology, and no further action. The final vote was 77 to 69; no New Englander supported the resolution, regardless of party. Even in the realm of settling disputes, Southern mores often prevailed.

Different men from different regions had different ideas about manhood, violence, lawfulness, and their larger implications—enough so that they sometimes required translators. Border-state congressmen often filled this gap.156 Hailing from Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, Missouri, and northern Virginia, many of them were slaveholders but their home states had mixed views about slavery, and their border location ensured ongoing interaction with the free-labor north.157 Border states had prosperous cities—Baltimore, St. Louis, Louisville—that followed a Northern model, with diverse populations and many free blacks. And perhaps most important of all for the purposes of congressional conciliation, border-state political passions often centered more on nativism than on slavery; even abolitionists were sometimes tolerated.158

Culturally bilingual, less defensive about antislavery rhetoric than their deeper south peers, and likely to be law-and-order Whigs, border-state congressmen were perfectly positioned to negotiate fights.159 It’s no accident that the period’s most renowned legislative compromisers were virtually all from border states, nor is it any more accidental that these same men were fight mediators of the first order.160

Fighting men, non-combatants, and compromisers: when congressmen studied pathways of power to chart a legislative course, they knew which men were in which categories and planned accordingly. The personal dynamics of the antebellum Congress were shaped by sectional patterns of violence. In ways that went beyond policies—even beyond the simmering issue of slavery—sectionalism mattered, shaping the balance of power on the floor.

French factored these patterns into his congressional calculations on an ongoing basis. When an argument moved from animated debate into head-to-head nastiness, he did what most of the congressional community did. He sized up the fighters and their grievances, decided what course of action would redeem reputations, watched closely to see what happened, and assessed the outcome. Men who behaved “manfully” earned kudos and clout; men who didn’t were scorned as cowards and their power on the floor fell accordingly. It was the calculus of congressional reputations, and fighting was a major variable.

Such calculations could be complex. French usually flipped through a mental fight checklist. Who was arguing? Were they Southern, Northern, or Western? Were they “honorable & fearless?”161 Had they dueled in the past? Was either man a proven coward, a non-combatant, a clergyman, or elderly? For Southerners, Southern-born Westerners, and fighting men generally, the fighting bar was set high and failing to meet it meant a lot. How serious was the offense? Was it words or a blow? Who witnessed it? Had either man used a hot-button insult? Puppy, rascal, scoundrel, coward, and liar were virtual invitations to duel. In certain circles, so was abolitionist. Were there any special circumstances? Was there a long-standing feud at play? Did the two men simply hate each other? Was one of them drunk? Were both of them drunk?

Almost every serious spat set French to calculating. In 1834, when Senator George Poindexter (AJ-MS) and Senator John Forsyth (J-GA) had a “gladiatorial set too” over Poindexter’s slurs against the Jackson administration, and Forsyth threw the lie (accused Poindexter of lying), French predicted a duel but the Senate settled it in “some way in secret session.”162 In 1838, when Henry Wise (W-VA) and Samuel Gholson (D-MS) exchanged harsh words (Gholson called Wise a “cowardly scoundrel”—a double whammy), French expected a fistfight given the two men’s track records, but Gholson’s arm was in a sling so “he could not make much of a fight.”163 Identifying each season’s best fighters, figuring the odds of a clash, sizing up likely winners and losers, watching for playoffs on the field of honor: in a sense, congressional fighting was a spectator sport.

And Congress was the major league. Although legislatures all over the Union had flash fights and bullying, clashes in Congress had added weight. Precedent-setting national policy was under debate. A national audience was judging the state of the nation by watching proceedings on the House and Senate floor. The Union-busting problem of slavery was never far from sight. And sectional habits gave some men a fighting advantage. It could have spelled disaster, and it ultimately did. But during the 1830s and 1840s, party bonds provided a vital counterbalance.164 Each party had its share of fighting men and non-combatants, and for the most part, parties cared for their own; attack a non-combatant and you risked a comeuppance from his combatant allies. In a very real way, there was safety in numbers.

But sometimes the demands of pride, section, and party pushed even non-combatants into combat. French discovered this for himself in 1838. When a New England Democrat was challenged to a duel, French had a surge of Yankee pride for a countryman and ally who was holding his own. But when things went horribly wrong and the unthinkable happened, French crossed a line. He plotted an assault on a congressman.