THE COMPROMISE OF 1850 AND THE BENTON-FOOTE SCUFFLE (1850)

As luck would have it, French reached his peak moment of congressional power as the nation’s next sectional crisis was taking form. At the time, his private life was going swimmingly. In 1837, he and Bess had had their first son, Frank. Five years later, he had built his family a large, comfortable house at 37 East Capitol Street, replete with an arbor-graced garden that boasted a three-tiered fountain with goldfish—the only goldfish in Washington aside from the fishpond on the Capitol grounds. His Washington insider status was apparent in his home decor; his lush red, gold-fringed parlor curtains were from the Supreme Court, bought by French when the Court was redecorated. His comfy, much-used study was on the top floor.1

French gained the House clerkship in December 1845 (and gained his second son, Ben, in February). That same year, the United States annexed Texas. Texans had declared independence from Mexico in 1836 with the aid of Southern militias and the Southern press, after which Southern settlers had flocked into the territory, exponentially increasing its slave population in the process. Their aim was Texas as a slave state.2

The vote over annexing Texas had been close. Just as Southerners hoped, adding it to the Union was an unequivocal boost to the spread of slavery and the Southern balance of power in the Union. Thus the flood of anti-annexation antislavery petitions to Congress throughout this period. And thus Adams’s continued insistence that the acquisition of Texas was a nefarious Southern ploy to expand slavery’s reach.3

Adams also insisted that the annexation of Texas was immoral. Mexico hadn’t conceded Texan independence, so annexing it was as good as declaring war. Sure enough, less than six months after Texas joined the Union, Mexican-American relations unraveled. When the newly elected president James K. Polk, an ardent expansionist, ordered troops into Texas to protect American claims, President Mariano Paredes of Mexico countered with troops of his own. By May 1846, a series of skirmishes had launched the Mexican War.

The Wilmot Proviso of 1846 was a direct result of that conflict. Proposed by Representative David Wilmot (D-PA) at the start of hostilities and unsuccessfully proposed twice more, each time failing in the South-friendly Senate, it banned slavery in land gained from Mexico. Although voted down, the proviso became a litmus test of loyalties: if you supported it, you were no friend of the South.

Whigs used this logic to tar French in his race for reelection in 1847. Given the House’s small Whig majority and the fact that some Northern Whigs had promised French their votes, the contest was close. Some Whig newspapers thought that French’s skills and popularity might preserve him his job.4 To prevent this outcome, Whigs put the proviso to use, telling their Southern wing that French supported the slavery-banning proposition and their Northern wing that he opposed it.5

It’s hard to say if that scheme cost French the clerkship, but whatever the reason, the former House member Thomas Campbell (W-TN) won by four votes. All but one of the Whig votes promised to French went to Campbell. For the most part, French took it in stride, happy to surrender the immense workload and “wear and tear of lungs.”6 But he was surprised that his friends and talents hadn’t kept him in office. He could only assume that he had lost his job for no sin other than being a Democrat.7 Convinced that he had taken a hit for the Democracy, French concluded that it owed him and looked forward to regaining the clerkship in the next Congress.

The lone Whig who stayed true to his word was John Quincy Adams—ever the contrarian—who told French that although the press said that no Whig would vote for him, “I profess to be a whig, and I shall vote for Mr. French.”8 After the election, the grateful French thanked him in person, little knowing that these would be his last words to Adams, who suffered a stroke in his House seat two months later, on February 21, 1848. Carried into the Speaker’s chamber, he lingered for two days; French made a tearful visit to the comatose Adams before he died.9 Appropriately enough, Adams’s last word on the floor was “No.” Near the end, he murmured thanks to the officers of the House.10 It was a fitting end for a man who had dedicated most of a decade and all of his energies to bedeviling Speakers and challenging clerks with his war against gag rules.

When the next Congress opened in 1849 with a Democratic majority, French felt sure that he’d regain the clerkship, but America’s victory in the Mexican War in 1848 complicated matters. The United States gained new lands whose slavery status had to be reckoned with, as did the national government’s right to restrict slavery in these territories, and a tangle of related issues: the boundaries of Texas, slavery in the District of Columbia, and the problem of fugitive slaves. By forcing the issue of slavery on Congress, national expansion raised fundamental questions about the sectional balance of power, the nature of the Union, and what kind of nation the United States would be.

Primed for the fateful decisions at hand, Northern and Southern congressmen arrived in Washington eager to seize every advantage, launching three weeks of savage, foot-stamping, name-calling arguments about selecting a Speaker. The stakes seemed too high for good faith or compromise. Accusations abounded as congressmen tried to determine the precise loyalties of each and every candidate. Did they favor the Wilmot Proviso? Did they advocate disunion over any and every compromise on slavery? Even nature seemed eager to tear the Capitol in two. Afraid that lightning would strike the building’s ninety-two-foot-tall mast “and kill Congress at a lick,” French joked darkly, Congress had taken down the mast.11

Ten days in, the House reached a breaking point.12 While discussing the speakership, William Duer (W-NY) called Richard Kidder Meade (D-VA) a disunionist. When Meade denied it, Duer called him a liar, Meade lunged at him, and the chamber went wild. The sergeant at arms from the previous Congress ran to Duer’s side to fend off raging slaveholders, but became so alarmed that he ran back for the mace—which did absolutely nothing to stem the tide of fury. Had “a bomb exploded in the hall, there could not have been greater excitement,” he later reported. (According to a more poetically inclined Globe reporter, “The House was like a heaving billow.”)13 Alarmed congressmen hustled to the galleries to protect their families; with no officers elected and no way to impose order, people feared a full-fledged riot and almost got one. They also almost got a duel, though Meade and Duer ultimately settled their differences.

It took some time to return the House to order. But minutes later, there was talk of disunion yet again. Enraged at the idea of Northerners branding Southerners disunionists, Robert Toombs (W-GA) swore his loyalty to the Union, but declared that if the House planned “to fix a national degradation upon half the states of this Confederacy, I am for disunion.” Other Southerners vowed that if the South was treated unfairly, they would keep the House disordered forever.14 Writing to his wife amid the “indescribable confusion,” David Outlaw could only moan, “I most sincerely wish I was at home.”15

Northerners responded to Southern threats as Northerners were wont to do: they demanded orderly debate. But some of them did so with defiance, dismissing threats as bluster and asserting their rights on the floor. Edward Baker (W-IL) met Toombs’s ultimatum by refusing to be “intimidated by threats of violence.… We are here as freemen, to speak for freemen; and we will speak and act as becomes us, in the face of the world.”16 Chauncey Cleveland (D-CT) took the same stand. Did the South expect the North to “forget that we are freemen—the representatives of freemen?” Did they think that the North “should yield our opinions, our principles to their dictation?”17 Both men were refusing to be gagged by threats of violence. It was an echo of six years past, but magnified by a mandate; Northerners wanted their congressmen to defend their rights. To make matters worse, by dismissing Southern bullying as bluster, Northerners threw the lie at Southerners and scoffed at their manhood, raising tempers even higher.

With Congress at a standstill, Meade pleaded for a compromise. Would no Northerner offer an olive branch? It would never happen, replied Joseph Root (FS-OH). After more than a week of Southern threats and grandstanding, no Northerner would dare appease a Southerner. His constituents would scorn his cowardice. (Or as Root more colorfully put it, any such Northerner should tell his children to “get their Sunday clothes on, for they would want to see their daddy for the last time.”)18 Several Northerners privately said the same thing to speakership candidate Howell Cobb (D-GA). Although they wanted to support him, “the threats and menaces of southern men … would destroy their position at home” by suggesting that they had voted “under the influence of these belligerent taunts.”19

After a three-week wrangle, Cobb was elected Speaker and attention turned to the election of the Clerk. Assuming that the Democracy owed him their support given his lost election, French was stunned to find several Democrats running against him. “My notions of honor do not exactly square with the idea of placing myself in the way of any democrat who has been immolated on the political altar,” he fumed in his diary. Even so, he thought that he could win. But Democrats chose the Philadelphia Pennsylvanian editor John Forney, “a peculiarly faithful ally of the south,” as their nominee.20 To French, it was a staggering display of party faithlessness. (In true French form, he dubbed this sin “Forneycation.”)21

Disappointed as he was, French resolved to hold back; his party had made its choice and he would let things play out. But when he heard that some Southern Democrats absolutely refused to vote for him, his “Yankee blood was up at once” and he declared himself a candidate.22 He later regretted it; his Yankee foot-stamping peeled away Democratic votes for Forney, as Forney later grumbled in the press.23 But French didn’t decide the election, although he tangled it; in a close contest with convoluted twists and turns that lasted for a week and twenty ballots, he received only a smattering of votes.24 The tide was turned by eight Southern Democrats who reelected the Tennessee Whig Thomas Campbell, putting section above party to give the clerkship to a Southerner.25 In 1847, French had lost the clerkship for being a Democrat. Now he had lost it for being a Northerner.

For French, a loyal doughface and longtime clerk with supportive friends on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line and both sides of the aisle, it was a stunning betrayal. For two decades, he had worked to preserve party ties between North, South, and West, singing a song of Union and Jackson, playing down talk of slavery and playing up talk of states’ rights. He had done this and more for the Democracy and the Union, pouring his heart, soul, and energies into an organization that he felt sure had the nation’s—and his—best interests at heart. Yet in French’s hour of need, his party had abandoned him. The Democracy had done what it did so often and so well: Southerners had served themselves and Northerners had knuckled under, and together they had cast him aside.26

This stark imbalance of power was nothing new. But in 1849, it had a sharp personal edge that forced French to reckon with some ugly truths; the corrupt bargain at the heart of the Democracy had been exposed. “One thing I have learned, and I intend to make a note of it,” he told his brother not long after his loss: “if a northern man will not bow, & knuckle, & prostrate himself in the dust before their high mightiness of the South, he must hope for nothing.”27 Doughface congressmen, “moulded into any shape their Southern taskmasters choose,” were little more than “whipped puppies,” he fumed, never saying—but surely knowing—that he himself had long fit that mold. French himself was through with such cowering: “I will see the South all d—nd to everlasting perdition before I will ever crook my thumb & forefinger, or open my lips in their defence.” Let Southerners turn to their “own servile race” for support.28 Northerners should defend their rights and interests and stop enslaving themselves. Though still loyal to the Democracy, French no longer trusted Southern Democrats.

His feelings mirrored the mood in Congress. The weeks of ultimatums set the tone for the session. Sectional passions were reaching new heights. Northerners were more confrontational than ever before. And a watchful, wary public was a palpable presence. Slaveholders and free-state men were throwing down.

Remarkably, this strife-ridden Congress produced one of the most famous compromises in American history: the so-called Compromise of 1850.29 A patchwork cluster of bills that occupied the entire ten-month session—the longest session since the founding of the government—it soothed but didn’t solve the slavery crisis. Men who were literally at each other’s throats ultimately came together for the sake of the Union; indeed, the raging sectional fury made the need for a national compromise that much more urgent. This volatile blend of intense sectionalism and intense nationalism would characterize congressional politics for years to come.

At the heart of this standoff were sectional rights: Southerners demanded equal rights in the territories, Northerners demanded equal rights on the floor. The alternative was unthinkable—degradation, a key word throughout the Compromise debate.30 Sectional honor was at stake in 1850, but not as a tool of debate as in “Cilley scenes” of times past. During the crisis of 1850, with the balance of power in the Union in question, sectional honor was the debate. Thus the newfound Northern belligerence.

And thus a shift in Southern bullying as well. Southerners had long held sway with man-to-man threats. Now, with the expansion and survival of slavery at stake, they began to threaten the institution of Congress and the Union with a new power, depicting the nation’s end times with alarming precision. The halls of Congress bloodied, disunion, civil war: Southerners paraded an array of horrors in this politics of ultimatums.31 Southern bullying had expanded exponentially, embracing the entire Union in its reach.

But even now, apart from a few stellar outbursts, Congress didn’t dissolve into a den of furies. Violence continued apace, but so did some degree of self-restraint. Even as they shoved, slugged, and threatened one another in the cross-fire of a crisis—indeed because of that crisis—congressmen abided by informal rules of combat that kept fighting fair, though like the terms of Union as a whole, these customs skewed Southern, compelling non-combatants to fight or risk dishonor.32 In essence, congressional combat was grounded on a South-centric spirit of compromise. And like the bonds of Union, without some degree of cooperation and mutual trust, Congress’s institutional bonds wouldn’t survive.

To see the rising tensions between fighting and fairness, it’s hard to think of a better case study than the dramatic 1850 clash between Senator Thomas Hart Benton (D-MO), the storied champion of the nation’s “manifest destiny” to spread across the continent, and Senator Henry Foote (D-MS), Benton’s far less storied colleague.

The two men had long disliked each other, and their mutual dislike had blossomed in the summer before the opening of the session. Early in 1849, Senator John C. Calhoun (D-SC) had orchestrated what came to be known as the Southern Address, a statement signed by a small group of Southern congressmen denouncing Northern aggression against Southern rights, denying Congress’s right to forbid slavery in new territories, and threatening secession. Not long after, the Missouri State Assembly adopted similar resolutions.33 Disturbed by Southern extremism and its implications for the Union, and eager to prevent agitation of the slavery question, Benton attacked the measures in electioneering speeches throughout Missouri for months, denouncing the extreme claims and downplaying the threat of secession.34 “There has been a cry of wolf when there is no wolf,” he later quipped.35

Alarmed by Benton’s politics and outraged at his implied sneer at Southern threats, several Southerners took him on. Foote did so with verve. Egged on by his friend Henry Wise—now a bullying consultant from afar—he published a lengthy letter to Wise full of abuse of Benton, accusing the Missourian of being willing to “sacrifice southern honor and southern prosperity on the altar of his own political advancement.” He continued in that vein for twenty pages.36 His sniping continued once Congress was in session.

Foote played a leading role in this slavery showdown. His first attempt to get what he wanted reached far beyond Benton; he threatened a mass Southern assault on Congress and civil warfare if a South-friendly bundle of compromises wasn’t hammered out in private—and soon. This was Southern bullying on a massive scale, so massive that few people believed it. But some did, and that meant something. They saw sectional combat in the Capitol as not only possible, but imminent.

When Foote failed to get his way with bullying writ large, he turned to bullying writ small, focusing his sights on Benton, a loud and aggressive opponent of his plan. Hoping to defeat Benton’s influence by damaging his reputation, Foote insulted him for weeks, with Benton grasping at rules and customs to defend himself without losing control and thereby losing the fight.

Finally, on April 17, 1850, Benton snapped. Throwing back his chair, he lunged at Foote, who responded by pulling a pistol and aiming it at Benton. Predictably, this produced chaos. Congressmen stampeded through the Senate to break up the fight (or get a better look). Some of their fellows howled for order in a panic. Mass pandemonium erupted in the galleries. A few moments later, Foote’s gun was taken from him and the chamber regained some semblance of order.

A crisis had been averted. But Benton refused to let the matter drop. The ensuing debate centered not on the simple fact of Foote’s gunplay, but rather on his motives and intentions: had he been fighting fair? After what the Globe might call a “lively debate,” with Northerners pushing for a formal investigation and Southerners dismissing the episode as too trivial to merit one, Vice President Millard Fillmore (W-NY) appointed an investigative committee. The next day, the Senate got back to business, eventually making its way to the subject of … the acceptance of antislavery petitions.37

The Senate committee then went to work. Over the course of several weeks, it examined forty-three witnesses, including senators, congressional staff, newspapermen, personal friends of both combatants, and even the shop clerk who sold Foote a pistol. The resulting 135-page report—filled with people’s thoughts about a fight and its fighters—reveals the patchwork of intricate and sometimes contradictory compromises that kept fighting fair and bridged divides, much like the Compromise of 1850 itself.

French emerged from his lost clerkship battle with his own patchwork of contradictions and compromises. For income, he patched together several jobs, cashing in on his congressional know-how by opening a claims office; doing some lobbying; and serving as a director and stockholder of the Magnetic Telegraph Company, and from 1847 to 1850 as its president. But his hard work didn’t garner much reward. His finances fluctuated throughout this period; neither lobbying nor lawyering promised a stable income. “We have plenty of business,” he wrote of his claims office in December 1850, “but it is of that sort which only pays if we are successful.”38 His loss of the clerkship—the office that his wife, Bess, said he preferred “to any other in the Union”—was a mighty loss indeed.39

By 1849, French’s politics were something of a patchwork as well. The betrayal of Southern Democrats in his election for Clerk had opened his eyes; although he remained a party activist, he no longer saw the Democracy as a forge of Union. From this point on, the Constitution would be French’s political touchstone. Fidelity to the Constitution—to French, “the wellspring of wisdom and concession”—would bind the nation, section to section, state to state, and man to man.40 The fellow feelings of Americans would secure those bonds; French saw the unifying power of such feelings among the Masons, a national brotherhood that came to play an increasingly central role in his life.41 With sectional tensions on the rise, French grasped at what he perceived as the nation’s fundamental spirit of fellowship and compromise.

Yet even as French fretted for the Union, he turned his face north. Convinced that Southern domination meant national ruin, he saw Northern resistance as the only way to level the balance of power: Northerners needed to fight for their rights. French’s near idol worship of Joshua Giddings in the 1850s was of a piece with his new state of mind; he deeply admired the Ohioan’s willingness to risk life and limb battling the Slave Power. French had long admired Northerners who stood down Southern bullies. Now he wanted a league of such men, and he wanted them to fight. And he wasn’t alone. During the debate over the Compromise of 1850, fighting for the Union began to take on troubling new dimensions—for French, for Congress, and for the nation.

THE FIGHTERS AND THEIR FIGHT

When the dust had settled after the tumultuous opening of the Thirty-first Congress, French did what came naturally: he wrote a poem—a “rather patriotic piece,” his twelve-year-old son, Frank, judged after reciting it.42 Alarmed at the sectional uproar (or as French’s poem put it: “That dark and dismal cloud that seems / Our Union to enfold”), French published “Good Wishes for the Union,” a call to arms for compromisers everywhere. His message was captured in the poem’s refrain: “Our Union cannot fall— / While each to all the rest is true, / Sure God WILL prosper all.” With selfish Southerners and faithless Democrats fresh on his mind, French was preaching national brotherhood and loyalty. Yet even in this ode to nationalism, he planted seeds of sectionalism; his poem cites every Northern and Middle Atlantic state by name, even encompassing Western territories, but mentions no state south of Virginia. His wounds were fresh and deep.

French had good reason to be alarmed. Political bonds of all kinds were fraying. Not only were the Whig and Democratic parties collapsing under the strain of sectional tensions, but even sectional allies were at odds. All told, Congress was split four ways over the issue of a compromise on slavery. There was a mix of Free Soilers, Northern Whigs, and Northern Democrats who opposed compromise and thought that slavery should be excluded from the West. There were Whigs who favored compromise and felt that the federal government had power over slavery in the territories. There were Democrats (Northerners and some Southerners) who favored compromise and thought that new territories should decide the issue of slavery for themselves. And there were Southern Democrats who opposed compromise, denied the federal government’s power over slavery, and demanded slavery’s expansion west.43 Even slaveholders were divided on the best way to handle the issue of slavery, as the Benton-Foote conflict shows all too well.

In a sense, the two men were bound to create conflict because their politics clashed and their practices didn’t; both men were congressional bullies of the first order. Forty-six years old, the Virginia-born Foote was slight, short, bald, and none too strong; he had a slight limp from a wound received in a duel.44 But he was a fighter; as a friend put it, Foote was “liable, somewhat, to be involved in disputes and personal difficulties.”45 That was an understatement. Foote fought legislative battles by insulting, belittling, and threatening his foes; at peak moments of oratorical wrath, he stamped his feet. (In the committee report, several observers noted that he barely had time to stamp each foot once before Benton exploded.)46 He earned his nickname—“Hangman Foote”—in 1848 when he told the aggressively antislavery John Parker Hale that if he ever set foot in Mississippi he’d be hanged, with Foote standing by to help. Foote called the nickname the most “severe humiliation” of his life, which was saying something given his congressional shenanigans.47

Not surprisingly, Foote was a frequent fighter. He fought four duels during his political career and was shot in three of them, suggesting that he was far better at shooting off his mouth than his gun.48 In addition, during his five years in the Senate he was involved in at least four brawls with senators, once exchanging blows with Jefferson Davis (D-MS) in their boardinghouse, an episode that prompted two near-duels; once exchanging blows with Simon Cameron (D-PA) on the Senate floor (as Sam Houston [D-TX] put it, the “eloquent and impassioned gentlemen got into each other’s hair”49); once slugging John C. Fremont (D-CA)—Benton’s son-in-law—just outside the Senate door, again raising talk of a duel (Fremont asked Cilley’s second, George W. Jones, to be his second); and once getting into a scratch fight with Solon Borland (D-AR) over the politics of John C. Calhoun.50 He also routinely bullied Northern non-combatants.51 So notorious was Foote’s fighting problem that a journalist set it to music, writing a mock “moral song” for children—and senators:

Grave Senators should never let

Their angry passions rise,

Their little hands were never made

To scratch each other’s eyes.52

Henry Foote, ca. 1845–60 (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Despite the mayhem, Foote was an educated man with refined tastes, as were many bullies; the fine art of congressional bullying went beyond back-alley brawling. Having pursued classical studies before training in the law, Foote sprinkled his lengthy and frequent oratorical forays with learned references, accompanied—as one reporter described it—by the “eloquent gestures of a galvanized frog.”53 Watching Foote perform in the Senate, Representative David Outlaw described him as a “talking machine” who quoted “Greek, Latin, the Bible, Shakespeare, Vattel, and heaven knows what else.” Foote was his “evil genius,” Outlaw groused to his wife, “for it so happens I hardly ever go into that chamber, and remain for half an hour, without [him] either making a speech, or interrupting some person who is speaking.” All in all, Outlaw concluded, “of all the men I ever heard, he is to me the most disagreable.”54

Many found the sixty-eight-year-old Benton equally disagreeable. French thought him the vainest man he’d ever known, citing as proof a time when he had seen Benton point to his signature on a document and pronounce it (with a portentousness that “Doct. Johnson could not have surpassed”) a name of world renown. But Benton had a right to be vain, French thought, ranking him as one of the nation’s greatest statesmen.55 Personally, French liked him. During the friendly house calls that filled most New Year’s days, the French family often called on the Bentons.

Born in North Carolina, Benton practiced law in Tennessee before moving to St. Louis; a notorious street brawl with Andrew Jackson featuring pistols, knives, fists, a whip, and a sword cane probably influenced the move, since it complicated Benton’s place in Tennessee politics, to say the least. (As Benton himself put it, “I am literally in hell.”)56 But in Missouri, Benton was no less combative; in 1817, he fought a duel with the opposing lawyer in a court case and killed him.57

In Congress, Benton’s fighting reputation preceded him; even as a newcomer, French was already factoring it into his congressional calculations.58 It was for good reason that Cilley’s friends turned to Benton for fighting advice. During the Missourian’s many years in the Senate, he came close to fighting a duel three times in addition to his 1850 fight with Foote, in one case throwing the lie at Henry Clay, who threw it right back. (Clay claimed that Benton had once said that if Andrew Jackson became president, congressmen would have to be armed at all times; they settled the matter off the floor.)59 Most recently, after an argument sparked by a debate over the slavery status of the Oregon Territory in 1848, Senator Andrew Butler (D-SC) had commenced duel negotiations with Benton, with Foote acting as Butler’s second. Foote’s delivery of Butler’s opening letter had so alarmed the entire Benton family, that—partly out of disdain for Foote—Benton had refused to act on it.60 Rumor also had it that Benton, a devoted family man who was so publicly affectionate with his children that he almost charmed the formidable John Quincy Adams, had promised his wife that he would never duel again.61 During the 1850 encounter, Foote’s sneering reference to Benton’s alleged cowardice in the Butler affair made matters worse.

Thomas Hart Benton, ca. 1845–55 (Courtesy of the Missouri History Museum, St. Louis)

Physically, Benton was Foote’s polar opposite. A large, hulking man, muscular, powerful, roughly six feet tall, he was an imposing figure when fully fired up. His towering temper matched his size. He “was not only a man of tremendous passions,” recalled Representative George Julian (FS-IN), but he was “unrivaled as a hater.… He was pre-eminently unforgiving.”62 Watching him in one of his rages, the ever-sardonic Adams described him as “the doughty knight of the stuffed cravat” abating “his manly wrath.”63 None too challenged in the ego department, Benton veered toward pomposity. Foote stamped; Benton strutted.64

One of Missouri’s first senators, Benton served in the Senate for a remarkable thirty years, and he never forgot it; in 1850, he was the senior senator in point of service. Foote wasn’t the only man to denounce him as a self-proclaimed Senate patriarch who routinely bullied men into compliance. Like Foote, “Old Bully Bottom Benton”—to quote Henry Wise—had a sarcastic turn.65 “When he wanted to torture an opponent,” a contemporary later recalled, “he had a way of elevating his voice into a rasping squeal of sarcasm which was intolerably exasperating and sometimes utterly maddening” and he used the word sir as “a formidable missile,” as during the exchange that led Andrew Butler to challenge him to a duel.66 When Butler accused Benton of leaking a document to the press, Benton declared, “I don’t quarrel, sir. I have fought several times, sir, and have fought for a funeral; fought to the death, sir; but I never quarrel.”67 (True to form, the Globe summed up the fiery exchange by noting: “[The scene was more than usually exciting at one time.]”)68

In personality alone, the two seemed destined to clash, but their clashing politics guaranteed it. Although both men were Southern Democrats hoping to save the Union, they differed in their views of sectionalism, slavery, and compromise—and in 1850, all three were bound in a bundle of controversy. Fearful that Southern ultimatums would destroy the Union, Benton opposed the expansion of slavery into the territories, a stance that Foote couldn’t fathom. California statehood proved their breaking point. When the state requested admission to the Union as a free state, Benton supported it but Foote wanted a bundled compromise hammered out privately in committee with California as a bargaining chip—to him, the best way to protect Southern rights and interests.69 Benton objected to this proposed “lump” of legislation, unwilling to allow the threats of a Southern minority to awe the majority into concessions.

To defeat Benton’s influence, Foote turned to bullying, attacking the Missourian’s reputation. By his logic, to prevent the South’s degradation, he had to degrade Benton. But even as his anti-Benton campaign began to build momentum, Foote attempted something far more dramatic. He tried to force through his plan of compromise by threatening the institution of Congress and the Union as a whole.

SECTIONAL DEGRADATION AND THE POLITICS OF ULTIMATUMS

Foote wasn’t alone in this politics of ultimatums. Disunion and civil war were topics of debate throughout the session. Southern congressmen had long used such threats to good effect. But in 1850, with a Union-shaping cluster of concerns on the table and sectional hostilities reaching new heights, those threats became more detailed, more violent, and more ambitious.70 Sectional bullying was coming into its own.

In the same way that the threat of a duel challenge had tipped the balance of power toward Southerners for decades, the threat of disunion held that balance in place during the crisis of 1850. In both cases, Southerners didn’t really want to follow through; few if any men wanted to fight a duel or dissolve the Union. During the speakership wrangle, Richard Kidder Meade had lunged at William Duer for suggesting as much. Threats don’t need to be fulfilled to be effective; the power of a threat is in the chance of its fulfillment, and Southerners had been flaunting their collective itchy trigger finger for decades.

The power behind these threats was the power behind all bullying: fear of humiliation and dishonor. Indeed, the entire Compromise debate was infused with talk of degradation and submission, honor and bravery, manhood and power, defiance and pride.71 Northerners, Southerners, and Westerners saw their rights under attack, and rights talk is honor talk; men who surrender their rights without resistance are cowards.72 So a discussion of sectional rights was bound to be painfully personal for congressmen and constituents alike.

This amped-up style of bullying began not long after the speakership contest was settled. While discussing California’s slavery status on January 22, 1850, Representative Thomas Clingman (W-NC) gave a speech so extreme that at least one newspaper editor thought that telegraph transmissions had mangled it. If the North intended “to degrade and utterly ruin the South, then we resist,” Clingman declared. “We do not love you, people of the North, enough to become your slaves.”73 To prevent such degradation, he proposed a Southern one-two punch. First, Southerners would fight as “Northern gentlemen” did, using calls for adjournment and calls for yeas and nays to bring the government to a dead halt. If that failed, then they would fight like Southerners—with violence. If Northerners tried to expel Southern troublemakers, there would be bloodshed. “Let them try that experiment,” he warned. Washington was slaveholding country, and “[w]e do not intend to leave it.” The end result would be a “collision” as electric as the Battle of Lexington, followed by the collapse of Congress.74 Clingman was describing the opening vista of a civil war. He was also offering fair warning.

A few weeks later, Foote took Clingman’s threats one step further. On February 18, free-state congressmen in the House had used the previous question to try to force through a resolution admitting California as a free state. In response, Southerners did what Clingman said they would do: they used parliamentary weapons to halt the debate until midnight, at which point the resolution would have to wait until March 4.75 Three days later, Foote rose to his feet in the Senate and proposed his solution to the California standstill: a select committee to hammer out a bundled “scheme of compromise.” To get his way, he issued an ultimatum: if a committee didn’t devise a compromise by Saturday, March 2—the last workday before the postponed California resolution would return to the House—then “so help me Heaven … during the next week occurrences are likely to take place of a nature to which I dare not do more than allude.” He knew what he was talking about, he insisted. “I have looked into the matter. I have conversed with members of both Houses of Congress; and I state, upon my honor, that unless we do something during the present week, I entertain not the least doubt that this subject will leave our jurisdiction, and leave it forever.”76

What did Foote mean? Newspapers were quick to tell the tale.77 According to unnamed congressional insiders, if no plan was forged by March 2, a pack of armed Southern congressmen would “break up the House.” Rumor had it that they would pick a fight and spark a melee as their opening gambit. Once open warfare broke out in the House, there would be no turning back. The Compromise debate would move to broader fields of battle than the floor of Congress. Foote was bringing Clingman’s threat to life.

Armed warfare in the House: the threat is so extreme that it’s hard to take seriously, particularly given its author, who was all too fond of what one newspaper called “gassing.”78 Thus the Globe’s nonresponse to Foote’s dire warning; it barely mentioned his ultimatum, even on the dreaded date of March 4. Within the context of the Globe, Foote’s threat doesn’t seem different from the rest of the session’s flame-throwing rhetoric.

But dig deeper and the threat’s full impact becomes clear: some people seriously considered its implications and some few believed it. Even dubious congressmen couldn’t rule out such an onslaught. In private, there was talk. North Carolina Whigs Willie Mangum and David Outlaw calculated how many of their colleagues were armed. Mangum thought seventy or eighty men—a third of the House. Outlaw thought fewer, though he was struck that some Northerners were armed.79 However unlikely bloodshed seemed at present, there were some “acts of aggression which will call for resistance, at any and every hazard,” he thought. “Death itself is preferable to degradation and dishonor.”80 To even the most moderate of men, some insults required violent resistance. However much Foote was gassing, there could come a time when his words would bear true.

Much of the press reached similar conclusions. Although a few Northern newspapers bought Foote’s threat wholesale, most considered gunplay possible but not probable. Armed Southerners probably wouldn’t break up the House, they advised, but hadn’t Southern congressmen proven time and again that they were capable of it?81 Here was the power of bullying firsthand. Although most threats were bluster, some of them weren’t, and it was hard to predict which ultimatums would be backed up with force. As Horace Mann (W-MA) put it when discussing three fights that broke out at the close of the previous session, “the spirit of fighting” was a hard thing to predict; it all “depends upon the men.” (In that case, the spirit of fighting had been clear; all three fights had featured a Southerner assaulting a Northerner.)82

A full-fledged battle within the walls of the Capitol was unlikely: so judged congressional insiders and the press. But what of the public? They showed what they thought in the days leading up to March 4. In anticipation of the congressional day of reckoning, people began streaming into Washington, fully prepared to see armed warfare between North and South in the House. Only after the day passed without bloodshed did the “great crowds which assembled here to see the Union dissolved by a general battle in the House of Reps” drift home, Outlaw told his wife.83

To these people, congressional ultimatums weren’t bluster; they seemed real enough to justify a visit to the Capitol—or to require some reassurance, as stray letters from congressmen comforting their friends and family make clear.84 Dangerous words were having an impact. And congressmen couldn’t help but notice. Some fretted about the damage that their extreme language could cause throughout the Union by fostering extremists. Others—particularly Southerners—thought that such language might do some good; as much as he regretted the repeated threats of disunion, Outlaw hoped that they would “cause the North to pause in their career before it is too late.”85

This was bullying writ large—very large. It was bullying as statecraft, and it had an impact, though not as planned. Like Outlaw, many Southerners were counting on its power to quell Northern aggression and resistance. It had worked one year past. After the passage of a resolution to end the slave trade in the District of Columbia, Southerners had threatened to dissolve the Union and then met in private to discuss “what they are pleased to denominate Southern Rights,” John Parker Hale told his wife. Frightened Northerners had responded by voting to reconsider the resolution. The end result, Hale had felt sure, would be “some insipid unmeaning motion for an inquiry into the expediency of doing something instead of the bold and manly resolution” that had already passed.86 In these cases, as in others, Southerners didn’t punch and shoot their way to victory. They used intimidation; they played on the fact that disunion seemed possible, if not probable. And in 1850, with Southerners mouthing plans of disunion instead of mere threats, it seemed more possible than ever before.87

But although a politics of ultimatums sometimes worked magic, during the high-stakes debate of 1850 it backfired, compelling Northern congressmen to dig in their heels and meet strut with strut. They boasted of their bravery in facing Southern threats. They bellowed about their right of free speech. And most of all, they presented themselves as champions of Northern rights. By standing up to slave-state men, they were defending the interests and honor of the North, just as bullying Southerners championed the South. In confronting their sectional antagonists, congressmen were literally and figuratively fighting for sectional rights.

To a certain degree, this had always been true in Congress. Both Jonathan Cilley and William Graves felt that they were fighting for “their people” and their section, Cilley—the taunted New Englander—perhaps most of all. Both men likewise felt that their honor and the honor of all that they represented were intertwined. But in 1850, sectional honor was the debate. This was performative representation of a powerful kind; congressmen were performing sectional rights on the floor, and their actions would shape sectional rights in the Union, though only if sustained by their home audience.

French counted on that fact, telling his brother that once Northerners knew “the game that is playing” in Congress, they would elect men who would fight for their rights.88 He himself reached new heights of respect for Northern fighting men during the 1850 debate, particularly for Joshua Giddings. Although French had long questioned Giddings’s aggressive abolitionism, he had always liked the Ohioan’s down-to-earth honesty; for French, “down-to-earth” was the highest praise that he could give. But during the Compromise crisis, he couldn’t praise Giddings’s manliness enough. Giddings was “one of the great men of this Nation,” French effused, “a high-minded fearless man, who is ready, I know, to become a martyr in a righteous cause.” French felt sure that Giddings, aided by “the God of battles,” would defeat “the oppressors” and save the Union.89

Giddings had pitted himself against Southern “oppressors” in 1849 during debate over slavery in California at the close of the previous session. When Southerners had threatened to rip out the hearts of antislavery men, Giddings scoffed. Richard Kidder Meade (D-VA) responded by bragging that the best way to manage antislavery congressmen was to keep them afraid for their lives. Unwilling to be bullied, Giddings condemned Meade’s words to his face, prompting Meade to grab Giddings’s collar and raise his fist, at which Southerners pulled the Virginian away. One reporter saw “a couple of gray heads bobbing about, and directly saw one of them hustled down the aisle … his arms seeming to be held in constraint by several friends.”90 At a time when French was raging against Southern dictation, this sort of display did his heart proud. Giddings was his beau ideal of a champion, a man who would stand up to bullying Southerners and right the balance of Union.

Senator John Parker Hale received similar praise from friends, constituents, and the press for his defense of Northern rights. When Andrew Butler (D-SC) called him a “mad man” during discussion of an antislavery petition, the normally genial Hale lost his temper, shooting back that Butler would have to “talk louder, and threaten more, and denounce more before he can shut my mouth here.” Northerners weren’t to be “frightened, sir, out of our rights … we are not to be frightened even by threats of danger personally to ourselves.” New Hampshire men would proudly defend their rights in Congress or in battle, let the enemy “come when they will, and where they will, and how they will.”91 Given Hale’s typically jovial style, this combative defense of Northern rights received ample press coverage.

So did his skillful skewering of ranting Southerners, as on May 20, 1848, when he responded to one of Foote’s taunts by asking for a dictionary so he could find the insult’s meaning, playing up the comedy of the moment and bringing down the house.92 In the Thirty-first Congress, the ongoing contest between Foote and Hale was much like the gag rule battle between Henry Wise and John Quincy Adams; the two men were partners in taunt and torment. Like Adams and Giddings, Hale was an antislavery toreador, but whereas Giddings fought with physical bravado and Adams fought with sarcasm and parliamentary savvy, Hale’s chosen weapon was humor. He was a master at deflating Southern bravado by reducing the Senate to laughter.

Such energized Northern resistance was striking. More striking still were the energized fears of congressmen about their safety on the floor. With hundreds of people milling about the Capitol, Joseph Woodward (D-SC) thought that if the Duer-Meade scuffle at the start of the session had been more serious, “in less than three minutes three hundred strangers would have rushed into this Hall” and produced a bloody melee, a scenario that was strikingly close to Foote’s doomsday threat.93 David Outlaw agreed. “In times of great excitement, as upon the slavery question[,] armed men might be admitted into this Hall, and in case of a personal collision this place might become a scene of bloodshed and confusion.”94 The press came to the same conclusion; a “bloody row” fueled by “outsiders” could happen at any time, and “civil war would thus commence in the Capitol.”95 The South’s “new game of frustration, or parliamentary hindrances,” could end no other way.96 Southern threats of civil war didn’t seem so outrageous after all, but the American public—not congressmen—would bring them to fruition.97

The session’s intense focus on bloodshed and sectional degradation is a reminder that sectional rights weren’t ethereal abstractions. They were close at hand and deeply personal, which gave them a special kind of power. As Volney Howard (D-TX) put it in 1850, if the Union was ever dissolved, it would be done not by calculation but as “a matter of feeling.”98 Fellow feeling might hold the Union together, but feelings of degradation could tear it apart. The gag rule debate had shown the importance of such feelings all too well. Northerners with little to say about the rule’s impact on slavery had plenty to say about its violation of their rights of free speech and representation, and the rule’s opponents played on that fact to bring it down.

Fairness, honor, rights, and feelings: the Union was built on these dangerously subjective constructs, as were the workings of its legislative branch. The constitutional pact was just that—a pact—and violating that founding compromise was dishonest and dishonorable. On this all sides could agree. But the precise boundaries and implications of that pact were still up for debate in 1850, so violations were often in the eye of the beholder.99 French’s ode to the Union confronted that challenge by asking each state to be true to the others. To French, fellow feeling and good faith were the Union’s only hope.

But fellow feeling was in short supply in 1850, even for French, who hoped that Northerners would remember “the spirit of ’76” and do all that they could to ensure that “the North is no longer cheated of its rights.”100 Cross-sectional trust was failing and fears of the consequences of that collapse were mounting. “At the very moment when forbearance and conciliation are of the first importance,” said David Outlaw, “these cardinal virtues, so essential to the peace of the country and the preservation of the Union, seem to have departed from our Legislative Halls.”101 Concern for the terms of Union was driving men apart.

THE IMPORTANCE OF FIGHTING FAIR

Ultimately, Foote’s large-scale sectional bullying campaign failed. As was ever his way, he went too far, making a threat too extreme to be believed—except by the people who came to Washington to witness the congressional apocalypse. But in the end, stalwart Northerners held firm, the day of reckoning passed without incident, and the torturous Compromise debate continued, as did Foote’s ongoing assault on Benton’s power and influence.

Opposed to the extension of slavery, disapproving of Foote’s backroom mode of compromise, and detesting Foote personally, Benton was a hulking roadblock of a problem. He was also a formidable opponent. Never a graceful speaker, his power was in the reach and recall of his knowledge. A master at amassing facts and figures, he wielded them like weapons during debates.

But Benton was a vulnerable target. His ambivalence toward slavery had long made him suspect among Southerners, who were more on guard than ever with its future at stake; Benton’s fight with Foote was one of many tussles between Southerners during that session.102 Much like French’s, Benton’s views on slavery were a web of contradictions; he disliked the institution, didn’t want to agitate the issue, disapproved of its extension, yet was willing to protect enslaved people as property. Neither a full Free Soiler nor a loyal Democrat, Benton embodied the mixed views of his home state of Missouri, which was grappling with the problem of slavery on the border of North and South. Many Southerners considered him downright traitorous; he was one of only two Southern senators not invited to Calhoun’s Southern caucus. His habit of dismissing Southern threats as empty bluster only made matters worse. Thus Benton’s nickname during the Compromise struggle: “Tommy the Traitor.”103

Foote seized on this logic in combatting Benton, trying repeatedly to prove that the Missourian was no Southerner and thus couldn’t be trusted with Southern rights. If Foote managed things deftly, he might even hurt Benton’s chance for reelection.104 With such clear benefits in mind, he held nothing back. As the committee report phrased it, Foote “indulged in personalities towards Mr. Benton of the most offensive and insulting character, which were calculated to arouse the fiercest resentment of the human bosom.”105

For Foote, such displays came naturally; he enjoyed Benton-baiting. Benton’s “overbearing demeanor,” his “boisterous denunciation,” his “sneerful innuendo”: Foote hated it all.106 On March 26, two weeks before his most renowned confrontation with Benton, Foote upped the ante. Eager to cut Benton off, Foote unleashed a string of insults, stating that Benton’s refusal to duel Butler had dishonored him, hinting at the possibility of a Foote-Benton duel, and accusing Benton of cowardice for tossing off insults while hiding behind privilege of debate and his refusal to obey “the obligatory force of the laws of honor.”107

Foote’s strategy was ingenious. By insulting Benton personally and to his face, he was daring Benton to challenge him to a duel. For Benton, this was a lose-lose situation. He didn’t want to fight a duel. But refusing to do so could destroy his reputation. So thought David Outlaw (W-NC). Although he detested the practice of dueling, he believed that some situations demanded it, and Benton was “in my judgement in that predicament.” To avoid “degradation,” the Missourian needed to “fight the first man who gives him occasion.”108 But given Benton’s foot-dragging in his near-duel with Andrew Butler two years past, Foote didn’t expect a challenge. And therein lay the power of his punch. He was trying to prove that Benton wasn’t a full-fledged Southern man and thus wasn’t loyal to the South. He drove that point home after each barrage of insults, asking Benton repeatedly: Do you abide by the code of honor?109 If the answer was yes, then a duel challenge was almost mandatory. If the answer was no, then Benton wasn’t a true Southerner. Clearly, Southerners could be bullied as effectively as Northerners.

For a long time, Benton didn’t rise to the challenge. Perhaps he held back for the sake of the Senate; patriarch that he was, maybe he was upholding its status. Perhaps at the age of sixty-eight, he wasn’t eager to fight. A devoted family man, maybe his violent days were past. Perhaps he was preserving his congressional gravitas. Or perhaps he was simply doing his best to advance the Compromise debate.

Whatever the reason, Benton restrained himself, defending his reputation by resorting to time-honored congressional traditions that kept fighting fair. For example, on one occasion, when Foote’s insults became too much for him, Benton magisterially gathered up his cloak and left the Senate chamber. Attacking a man in his absence was unfair and thus frowned upon; it was “not in accordance with what a gentleman should do,” one victim argued.110 By leaving the room, Benton was trying to cut Foote off.111 But Foote continued his “personalities” long after Benton had gone.112

On other occasions, Benton defended himself with a “personal explanation.” According to custom, an embattled congressman had the right to demand a few minutes to “defend himself as a man of honor” before colleagues, the press, and the nation.113 Unless there was an objection—which almost never happened—people who requested personal explanations were immediately given the floor, overriding all formal rules of order, and they couldn’t be interrupted.114 These explanations weren’t without their difficulties; as one Speaker complained, when the rules were suspended, it was near impossible to determine “what language is strictly in order,” and indeed, Benton’s explanations were sometimes filled with threats and personalities.115 But given their national audience, congressmen wanted a fair chance to defend their name.

Most explanations were sparked by newspaper accounts of congressional debates. Newspapers assailed congressmen beyond their reach; personal explanations were safe havens for fighting back. And fight back Benton did. The day after Foote taunted him on March 26, he declared the National Intelligencer’s version of Foote’s remarks “a lying account from the beginning to the end.” According to the Intelligencer, Foote had accused Benton of talking big because he couldn’t be attacked: he was “shielded by his age, his open disavowal of the obligatory force of the laws of honor, and his senatorial privileges.” Foote was calling him a coward. Foote had said no such thing, Benton roared—plus, it was a lie. He wasn’t too old to fight; insult him off the floor and you would know his age “without consulting the calendar.” He decided honor disputes on a case-by-case basis. And he never hid behind his privileges. If the Senate allowed these kinds of insults to continue, he concluded, “I mean from this time forth to protect myself—cost what it may.”

That statement would come back to haunt him. Hearing it, many onlookers—including Foote—thought that Benton was giving Foote fair warning of a pending street fight. It followed the conventional format exactly and was a favorite ploy of non-duelists who wanted to defend their name. In place of a duel, they typically declared that they would defend themselves “wherever assailed.”116 Once fair warning had been given, both parties would arm themselves with weapons and friends, and watch for a chance encounter on the street, which usually involved “pushing, scuffling, pointing of pistols, calling of names, and great disturbance of peaceable bystanders.”117

These “irregular” or “informal meetings” were substitute duels. Understood to be “the usual last resort of the non-duellist,” they became increasingly common in the 1850s with the rise of Northern resistance to Southern threats.118 Onlookers expected one after the Meade (D-VA) versus Duer (W-NY) outburst that started the session, given the involvement of a feisty Northerner.119 Street fights were a sectional compromise that enabled non-duelists to defend their name on equal terms. They made fighting fair.

Thus Foote’s assumptions about Benton’s declared willingness to defend himself, come what may. Foote “expected to be attacked on his way going to or returning from the Senate, and about the capitol buildings,” he told one friend.120 Benton was “a man of courage,” warned another. “[H]e would do whatever he said he would, and … Mr. Foote ought to be prepared to defend himself.”121 A fellow senator later chided Foote and Benton for not fighting on the street. “There is plenty of room out of the Senate,” he scolded. “[T]he streets are large, the grounds are spacious; and it is said there are good battlegrounds, if gentlemen choose to occupy them.”122

So Foote donned a pistol, watched, and waited. Several times, he asked friends if he should challenge Benton to a duel. Did public opinion seem to demand it? Foote, for one, preferred it. Given that “this matter was destined to terminate in a difficulty,” he preferred to settle it honorably in a duel than to grapple on the street, where Foote was bound to lose, though given Foote’s track record, a duel wasn’t likely to go better.123 But Benton never attacked. Even when the two brushed past each other on Pennsylvania Avenue, nothing happened. Foote could only conclude that Benton was “a recreant coward.”124

It was Foote’s renewed and reinforced charge of cowardice that pushed things too far on April 17, the day Benton snapped. A few days after passing Benton in the street, Foote threw the charge at Benton, but had gotten only halfway through the insult when Benton sprang to his feet, kicking aside his chair so violently that he toppled a glass from his desk. (Reporters in the galleries described the “breaking of glass, a movement among the desks, a rising among the crowd in the galleries,” and “a sort of crashing in the neighborhood of Benton’s seat.”)125 On seeing Benton head his way “with an expression of countenance which indicated a resolve for no good purpose,” Foote retreated backward down the aisle toward the vice president’s chair, pistol in hand. In a moment “almost every Senator was on his feet, and calls to ‘order’; demands for the Sergeant-at-Arms; requests that Senators would take their seats, from the Chair and from individual Senators, were repeatedly made.”126

Henry Dodge (D-WI) tried to restrain Benton, who dramatically bared his breast and yelled, “‘I have no pistols!’ ‘Let him fire!’ ‘I disdain to carry arms!’ ‘Stand out of the way, and let the assassin fire!’”127 Witnesses saw him open his jacket and bare his breast as he bellowed. At this point, a senator grabbed Foote’s pistol and locked it in his desk, and for the moment the fireworks were over.

But the controversy wasn’t. Foote and Benton immediately began to argue about motives and intentions. Foote insisted that he had acted in self-defense. Benton insisted that Foote was an assassin inventing excuses—a serious charge because it suggested that Foote had taken “unmanly” advantage; by pointing a pistol at an unarmed man, he wasn’t fighting fair.128 Benton had opened his jacket to prove that he had no gun for just this reason.129 Foote’s howling objections to the charge suggest its seriousness.

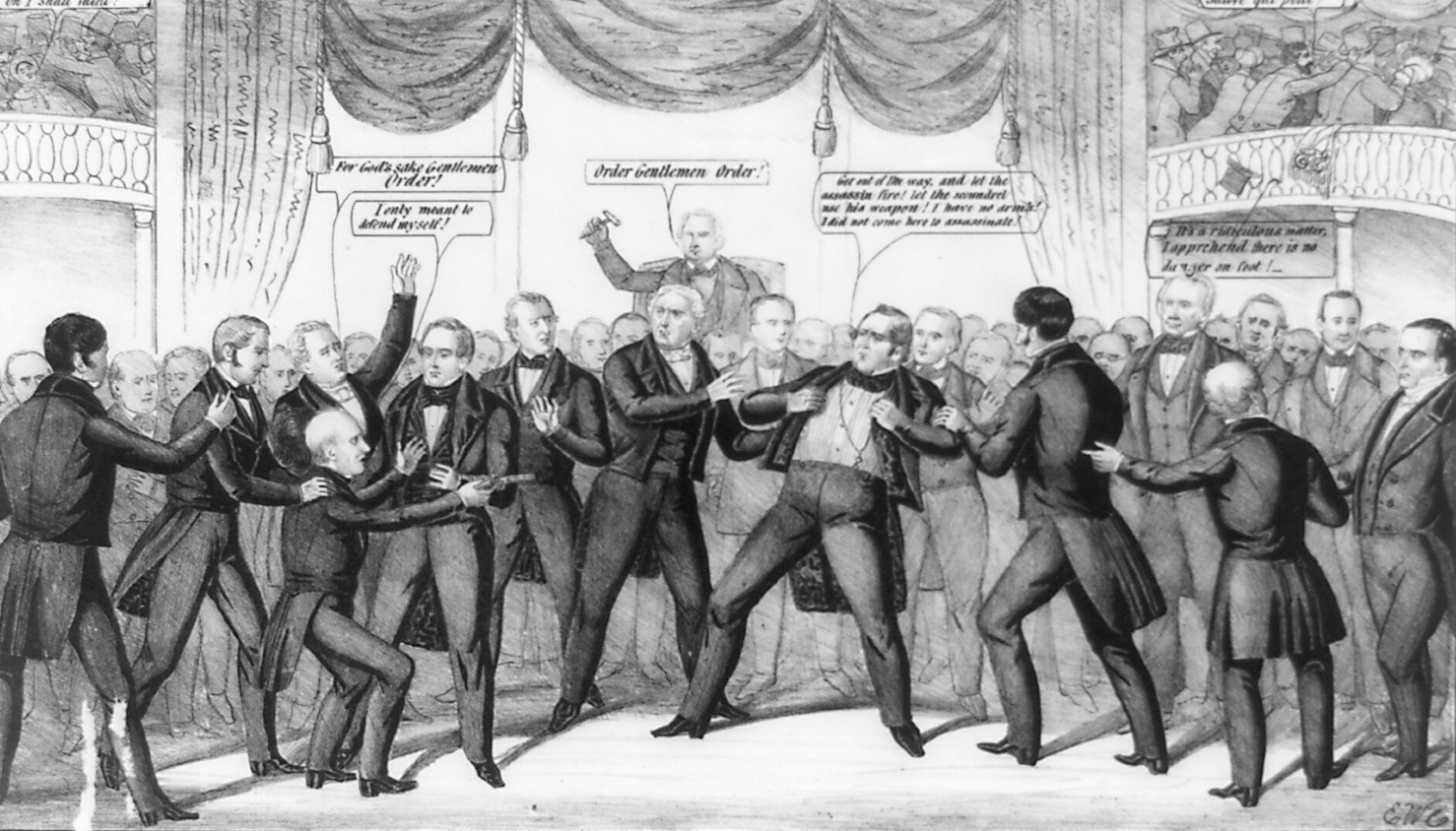

An 1850 cartoon depicting the Benton-Foote scuffle. Benton is throwing open his coat and bellowing, “Let the assassin fire!” as people in the galleries flee in panic. (Scene in Uncle Sam’s Senate, 17th April 1850, by Edward W. Clay, 1850. Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

To prevent such unfair matches, when two men seemed likely to fight, brother congressmen usually did an instinctive weapon check, eyeing jackets and vest coat pockets for the bulge of a gun or a flash of metal. If one man was unarmed, people typically intervened. When no one was armed, the fighters often were left to their own devices; it seemed only fair. In 1858, this scenario played out in the House when Augustus Wright (D-GA) noticed a fist-clenched stranger standing in front of Francis Burton Craige (D-NC); convinced that Craige was the stronger man, Wright went back to work—which speaks volumes about the level of violence that seemed normal on the floor. But when Wright spotted a weapon under the stranger’s coat, he leaped to his feet to prevent an “assassination.” Even then, he held back as the two men wrestled, ready to intervene if the stranger reached for his weapon. (And he had two: a knife and a revolver.)130

The confrontation between Foote and Benton was similarly unbalanced, but it fell to an investigative committee to determine the details and pass judgment. In the meantime, the Senate got back to business. And much as people had flocked to Washington in March to see a whole-House rumble, they filled the galleries the day after the Foote-Benton fracas to see what came next. As the Boston Courier reported, the galleries were jammed full of people expecting something “in the shape of a grand finale.” When business got under way and Foote rose to complete the speech that Benton had “so unceremoniously cut short,” the room hushed and the audience leaned forward. Benton sat nearby, nervously twirling a piece of paper. Would there be “another rush, another melée, another scamper, and another pistol drawn?” The entire chamber was “in an agony of suspense.” But Foote merely surrendered the floor and sat down, at which Benton took an audibly deep breath. Later that day, he sarcastically noted how “harmonious” the Senate seemed.131 With disharmony relegated to an investigative committee, the Senate was moving on.

“PUBLIC EXPLANATION IS NECESSARY”

As dramatic as the events of April 17 had been, in the end not much happened. The investigative committee did little more than condemn “personalities” and the wearing of arms in the halls of Congress, advising the Senate to take no action, which is precisely what the Senate did.132 Given this nonresponse, it’s tempting to dismiss the episode as political theater. But in his testimony, Foote noted that he had planned a path of retreat from Benton that put fewer senators in the path of his gun if he fired it. And many people assumed that Benton would have mauled Foote had he gotten hold of him.133 To the fighters and their audiences alike, the chance of bloodshed was very real.134

And the nation was watching. With the rise of the telegraph, the American public was witnessing congressional scuffles with ever-increasing speed and efficiency. “Washington is as near to us now as our up-town wards,” gushed the New York Express in 1846. “We can almost hear through the Telegraph, members of Congress as they speak.”135 Beginning with a small-scale experiment in Washington in 1844, the telegraph was spreading throughout the country, drastically reducing the news lag around the nation, and congressmen had to grapple with the impact.136 Not only did they have less time and power to tame their words, but it was difficult if not impossible to speak to different audiences with different voices. When the abolitionists Benjamin Wade (W-OH) and Charles Sumner (FS-MA) denounced the Slave Power while in their home states, Clement Clay (D-AL) took offense in Washington: How could these men “who profess to abhor and contemn us” up north “make the acquaintance of slaveholders, salute them as equals,” and “cordially grasp their hands as friends” in Washington?137 By networking the nation during a rising sectional crisis, the telegraph complicated national politics.

Ever and always at the crossroads of history, French played a role in this dramatic transformation; from 1847 to 1850 he was president of the Magnetic Telegraph Company, an enterprise that he discovered through his friend F.O.J. Smith (his son Frank’s namesake), one of three men that Samuel Morse chose to promote telegraphy at the dawning of the enterprise.138 The company had incorporated to create a telegraph line from Washington to New York, accomplishing the task in June 1846. The job not only sent French traveling about on telegraph business, occasionally putting him out in the field stringing wires, but it also made him something of an innovator in the use of telegraphy in politics. The presidential election of 1848 was the first election in which all states voted on the same day, and thus the first election in which the telegraph gathered returns. In preparation for it, French kept the telegraph offices in Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Jersey City open all night from November 7 through November 10, paying workers overtime and urging them to “avoid any partiality … during the excitement” so that biased reporting wouldn’t sway the results—a new fear for a new age.139 Six months earlier, he had paid for the telegraphic transmission of the Democratic Convention out of his own pocket.140 (French also may have been a telegraph pioneer outside of politics; according to one source, the first poem to be telegraphed was written by B. B. French.)141

After reading his first telegraph transmission in 1843, French had immediately grasped its political impact: whatever happened in “the heart here in Washington, will be instantly known to all the extremities of this widespread Union!”142 In the aftermath of the Foote-Benton clash, this realization caused a shock of recognition. Minutes after people settled back into their seats, Henry Clay—ever the great compromiser—followed the lead of Jefferson’s Parliamentary Manual and asked both men to “pledge themselves, in their places, to the Senate, that they will not proceed further in this matter,” meaning they would promise not to duel. Both men refused, Benton declaring that he would rather “rot in jail” than pledge to anything that implied his guilt, and Foote insisting that he had done nothing wrong and would take “no further remedy,” though as a “man of honor” he would do whatever he was “invited” to do, meaning that if Benton challenged him to a duel, he would accept. Sensing a stalemate and hoping for better luck out of the public eye, Willie Mangum (W-NC) suggested closing the Senate doors.

“I trust not,” Foote blurted, as senators echoed, “oh, no.” “I hope my friend will not insist upon it, when public explanation is necessary on my part.” Hale agreed, noting that due to the telegraph’s “lightning speed,” by sundown in St. Louis, it would be rumored “that there has been a fight on the floor of the American Senate, and several Senators have been shot and are weltering in their gore.” The image brought a laugh, but Hale had a point. A formal investigation was essential, not just for “vindicating the character of the Senate, but to set history right, and inform the public as to what did take place.” If the Senate didn’t take immediate action, public opinion would run wild. (The challenges of viral news coverage have long roots.)

Indeed, even with immediate action, news of the encounter spread with lightning speed. The next day, headlines were screaming in Boston and New York, and within forty-eight hours the Milwaukee Sentinel and Gazette announced: “By Telegraph. A ROW IN THE SENATE! COLLISION BETWEEN FOOTE AND BENTON! PISTOL DRAWN!” Just as Hale predicted, the facts got scrambled. Even before April 17, news had spread nationwide that Foote was going to challenge Benton to a duel; one newspaper even reported Benton’s death at Foote’s hand (though the report came from an April Fools’ Day telegraph transmission). Here was the answer to the question asked by countless congressmen. Why bother with the tedium of an investigation if no action was ever taken? Because it would set the record straight and suggest to the public that Congress had taken matters in hand. It would preserve the image—and ideally, the reality—of Congress as the headquarters of national compromise.

The public was watching. Indeed, the dispute was partly caused by the public eye. It was the publicity of Foote’s insults that most riled Benton. From the start of the session, Foote’s ongoing onslaught had received ample press coverage, and Benton was up for reelection. During the investigation, he questioned committee witnesses on this very point: Had they heard Foote say anything about drumming him out of the Democratic Party? Did Foote have correspondents in Missouri? Was he involved in a recent attack on Benton in the Missouri Statesman? More than fifty pages of the report center on newspaper accounts of the two men’s exchanges. Benton and Foote were fighting for public opinion.

The two men were equally obsessed with the written coverage of Foote’s insults. Foote had tampered with the press coverage of their confrontations to make himself look good, Benton told the committee, and it was bad form to privately edit the record of a personal insult after the fact. Far fairer to correct newspaper accounts of fights and insults in person in the Senate before the people who had heard them spoken and could distinguish right from wrong. To Benton, this was “the only way that honor can ever do.… A public correction of public personalities is the only thing that can be endured in a land of civilization.”143

Seconds later, Foote admitted that he had indeed tampered with the press coverage of his insults, but for good reason: he spoke quickly and was hard to hear. But he had made his edits “hurriedly” in his seat and hadn’t changed his meaning. If anything, he had softened his insults, he claimed. On the floor, he had attacked Benton for his cowardice in his 1848 honor dispute with Andrew Butler, now amicably settled. But because a senator sitting nearby murmured to Foote that mentioning a settled honor dispute was an “indiscretion,” Foote removed all mention of it from a reporter’s notes—though he’d be happy to restore it, he sneered.144

The tables were turned when Foote read the National Intelligencer’s account of the scuffle. In a statement published in the paper and reprinted around the country, he protested that he hadn’t “retreated” from Benton, as the Intelligencer reported. He had “glided” into a “defensive attitude.”145 This wasn’t mere silliness on Foote’s part, as silly as it was. Two senators had told him that he shouldn’t have run from Benton: Andrew Butler had blurted it out as Foote dashed past, and Willard Hall (D-MO) thought that Foote’s “enemies might say that he was actuated by fear.”146 Foote didn’t want to look like a coward in the public eye.

Both men were grappling with the challenges of national press coverage in the age of the telegraph. Reporters saw things differently and reported different things for different reasons, news spread with its own speed and logic, facts got scrambled with no time for correction, the public drew its own conclusions, and congressmen didn’t control this process, try as they might. Both Foote and Benton tried to shape their spin, but neither emerged from the episode unscathed.147

Many newspapers berated one or the other combatant with regional flair. Southern writers focused on the code of honor. Benton hadn’t fought fair, one paper argued. “This swearing one’s life against a man … so feeble in health as Gen. Foote” was not “entirely comme il faut.”148 As the “assailed party” (an arguable point), Foote had done right, claimed another. Under the code of honor, Foote had the choice of weapons, and a pistol was the most “Patrician” choice.149 Northern newspapers focused on parliamentary rules, denouncing Southern violence and insisting that someone should have called Foote to order. Reporting for the New-York Tribune, the antislavery advocate Jane Swisshelm—the first woman admitted to the reporters gallery (on the very day of the scuffle)—approved of Benton’s politics but regretted that he had “meditated any personal chastisement,” the product, she assumed, of a Southern education.150 The Foote-friendly Richmond Enquirer countered by playing the gender card, denouncing Swisshelm as “a disgrace to her sex” who was ill equipped to judge “a champion of the South.”151

Some newspapers condemned both men as well as Congress. A Pennsylvania paper took the long view, declaring the incident “a disgrace to the Nineteenth Century.”152 A Vermont paper waxed histrionic: “O Senators and Pistols! O Gunpowder and dignity! O Law-makers and bullets! Shame, shame!”153 The real villains were “Senatorial bullies,” charged a New Jersey paper: “instead of minding the business of their constituents, they—these grave Senators—only think of it!—are daring one another, almost daily, like schoolboys, to knock chips off their hats.”154 The solution was simple, claimed the Boston Herald: “If one-half of our Congressmen would kill the other half, and then commit suicide themselves, we think the country would gain by the operation.”155

Fighting was deplorable and something should be done: it was a lamentation speech writ large. But just as such hand-wringing accomplished little, its press equivalent rang hollow. Even as the press condemned congressional fisticuffs, it cheered and booed combatants with full force. National compromises were being forged by congressional gladiators egged on by a national audience, North, South, and West, and the nation’s ongoing slavery debate gave them plenty to fight about. Fence straddlers on the issue of slavery would find it increasingly hard to find electoral traction. Benton suffered this fate. With his mixed views on slavery, he lost reelection to the Senate in 1851, a stunning defeat after thirty years of service. There were bad times ahead.

For the moment, however, there was peace. Four months after the Foote-Benton scuffle, the Senate passed a series of bills that the House passed one month later. California was admitted as a free state; popular sovereignty would decide the fate of slavery in New Mexico and the Utah Territory; slavery was preserved in the national capital, though the slave trade was banned; a stronger Fugitive Slave Act would require all U.S. citizens to assist in the capture and return of runaway slaves; and Texas gave up some of its western land and received compensation.

Compromise and community had prevailed in Washington—a fact worth celebrating—and on the evening of Saturday, September 7, with California newly granted statehood, celebrate Washington did. Fireworks boomed. There was a hundred-gun salute. The Marine Band marched down Pennsylvania Avenue playing “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “Yankee Doodle.” Crowds went from boardinghouse to boardinghouse applauding congressmen, who were all too happy to speechify in response. According to one onlooker, it was “a night on which it was the duty of every patriot to get drunk,” and congressmen did their duty. (The next day, a badly hungover Henry Foote blamed his stomach trouble on “bad fruit.”) Dr. Jonathan Foltz, an attending physician to presidents and duelists (he was present at the Cilley-Graves duel), noted that he had “never before known so much excitement upon the passage of any law.”156 Congress was receiving an all-too-rare standing ovation, evidence of how dire the crisis had seemed.

But as much as the Compromise soothed a sectional crisis, it had a mixed impact on sectional sensibilities. The sustained Southern bullying campaign had schooled Northern onlookers in the gut realities of Slave Power dictation. Proudly proclaimed a policy and expanded to include the institution of Congress and the Union, Southern ultimatums and threats drove home the power and humiliation of Southern bullying. Just as French hoped, Northerners were seeing Congress’s skewed dynamics for themselves—not for the first time, but with a new power. They emerged from the crisis of 1850 with a keener sense of their rights and a sharper understanding of the power of Southern threats.

They also gained powerful models of resistance. The many men who vocally defended Northern rights on the floor taught home audiences what Northern resistance felt like. A letter to John Parker Hale in April 1850 shows the personal impact of this sectional combat on a home audience; the writer praised Hale for standing up to the Slave Power but worried about “the degradation of the North,” which would inspire feelings of “self degradation.” For constituents as well as congressmen, the link between sectional honor and personal honor was profound, and congressmen were an all-important link between the two in North and South alike.157

Thus the paradoxical outcome of the 1850 Compromise crisis. On the one hand, Americans gained a deeper appreciation of the Union and its fragility—an appreciation born of that fragility. On the other hand, they gained deeper convictions and stronger feelings about the very things that were threatening that fragile Union: slavery, sectional rights, and fear of sectional degradation.

It was both the nation’s and Franklin Pierce’s bad fortune for him to become president in 1853 at this time of tensions and paradoxes. A man with a foot in both sectional camps, a Northerner who catered to Southern interests for the sake of the Union and his party, Pierce was the ultimate compromise candidate, a logical choice at a time of crisis-born compromises. But his concessions would prove deadly. In 1854, when the slavery status of the Kansas and Nebraska territories came up for debate, Pierce’s South-centric statecraft would rekindle the crisis of 1850 and magnify it tenfold, launching a national crisis that would catch French in the cross-fire.

As Pierce’s longtime friend and supporter, French gave the Pierce campaign his all, though it wasn’t easy. It was hard to wage a national campaign at a time of sectional strife, and as a disillusioned Democrat, French faced personal challenges in waving the party flag. But he so deeply believed in Pierce as the man of the hour, so firmly believed that Democratic policies could save the Union, and was so good at the letter-writing, backslapping, hand-shaking, and songwriting that went into successful campaigning, that he devoted himself to the cause. In a sense, French had been training for the Pierce campaign for decades.