When dealing with metrics, we need to be careful and walk a fine line between practicality and innovation. Metrics are often hardwired in companies’ DNA, and it may be difficult, if not impossible, to change them or to gain acceptance of new metrics that might better reflect the actual health of your business. It is important for our purposes to look at metrics through the Hyper-Social lens and to see how companies are measuring the impact of their Hyper-Social activities on their business.

Hyper-Social companies consider tribes to be more important than market segments; they are human- and customer-centric instead of company- or product-centric, and they think about knowledge networks instead of information channels. While many companies have adopted customer-centric metrics like customer loyalty and customer equity–based metrics [focusing on the net present value (NPV) of a customer’s future purchases], few have adopted tribal equity–based metrics or knowledge-based metrics. Few also truly measure the impact of word of mouth on customer equity, even though research has shown that customers who are acquired by positive word-of-mouth activity can have twice the customer lifetime value of customers who are acquired via marketing-induced programs, and that word-of-mouth customers can bring in twice the number of new customers through their referrals.1

Hyper-Social companies also consider their customer interaction departments, including marketing and customer service, as investments in customer equity, not as cost centers. They also consider their talent to be assets, not disposable commodities the way most other companies do. Alan Webber, the cofounder of Fast Company, talked to us about this phenomenon as follows: “It’s my sense that in large publicly traded corporations, where the finance function and the mandate to drive up shareholder value is still the default mindset, those organizations are locked into a mental model that prohibits them from really valuing the human dimension. They want what people can contribute, but they don’t want to give value to it, because it’s very complicated to manage people, and it’s very easy to manage numbers.”

In the next section of this chapter, we explain why it is important to be practical and argue that companies should measure the impact of Hyper-Social activities on their business processes, just as they measure the impact of any other program. We will also review why companies should focus on the metrics that matter, not just the ones that they can measure easily. And finally, we will take a walk on the wild side and talk about potential new metrics that Hyper-Social organizations might want to monitor.

It’s exciting to invent new metrics that may be better at gauging the true health of your business than the ones that are currently in place; however, you need to balance that excitement with deep practicality. You see, most people who are in charge of business processes already have fixed ways in which they measure their business—and in most cases, the number of key performance indicators that they are tracking is in single digits. Chances are that if you don’t report the impact of your Hyper-Social activities on these business processes using the same metrics, your programs will remain on the fringe of the organization and never become mainstream.

That is exactly what we have found in our yearly Tribalization of Business Study, where we gather information from more than 500 companies on how they measure the effectiveness of their community and social media initiatives. Many companies are struggling with how to measure the impact of Hyper-Sociality on their businesses. In what we interpret as signs of an early market, we found many companies using advertising metrics when measuring the impact of online communities—time spent on the site and number of page views. Needless to say, most of those companies are not satisfied with their community initiatives and are not making much progress on scaling their Hyper-Sociality.

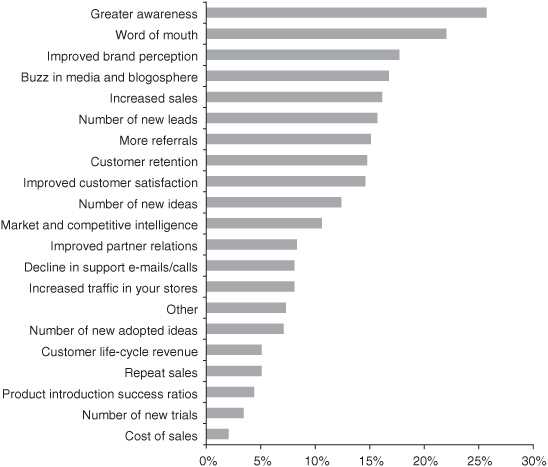

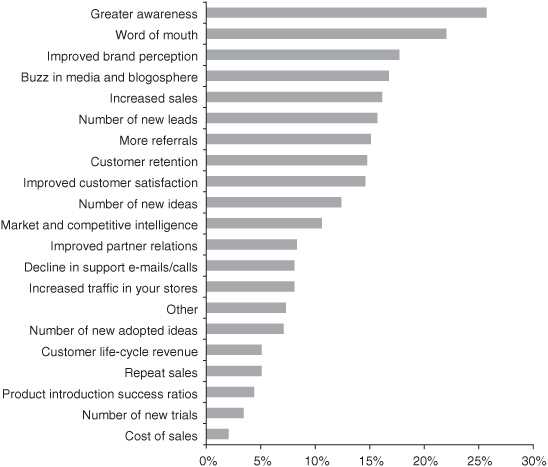

In fact, we could characterize the whole social measurement space as one of mass confusion. Take a look at the results shown in Figure 11-1, which illustrate our point. We found that the top five business objectives for communities are generate more word of mouth (38 percent), increase customer loyalty (34 percent), increase product or brand awareness (30 percent), bring outside ideas into the organization (29 percent), and improve customer support quality (23 percent). The same study found that the top five business measures are greater awareness (26 percent), word of mouth (22 percent), improved brand perception (18 percent), buzz in media and the blogosphere (17 percent), and increased sales (16 percent).

You see the disconnect? Referrals, customer retention, and customer satisfaction are in seventh, eighth, and ninth place—even though increasing customer loyalty ranked as the second most important objective. And the number of new ideas and number of newly adopted ideas are in tenth and sixteenth place, respectively, even though bringing in new ideas is the fourth most important goal. And look at customer life-cycle revenue and product introduction success ratios, two measures that you would expect companies that care about customer loyalty and bringing new ideas inside the company would measure—they did not show up until seventeenth and nineteenth place, respectively.

Figure 11-1 Top Five Business Measures of Community Success

Those organizations that are happiest with their online community initiatives are those that measure the impact of those communities the exact same way you would measure the impact of any other program on a particular business process. So, if you measure the impact of a focus group on product innovation in a certain way, or the impact of your call center on customer loyalty, then you should also measure the impact of your product innovation community or your customer support community the exact same way. Some companies, like Intuit, take this idea a step further and create centers for excellence, cross-functional teams that are funded by the different business units that derive benefits from those initiatives. If you extract funding from the various operating groups within your company, that will naturally force you to report the benefits to those groups in the same way as they measure the impact of other programs. This model is especially suited for companies that have more mature online communities, where community members start crossing organizational boundaries by giving product ideas in your customer support forums or supporting complaints in your product innovation communities.

So first and foremost, be pragmatic—by demonstrating that your Hyper-Social programs affect the various business processes that they are supposed to support, you will help those programs gain much-needed legitimacy. Once you get there, you can start looking for alternatives that best measure the long-term impact of Hyper-Sociality on your business and compare it to that of other, more short-term-focused programs.

In an online world, almost everything can be measured. The result: people become enamored with what they can measure, and measure far too many things. As Alan Webber, the cofounder of Fast Company, told us: “If you measure too many things, you might as well measure nothing.” Some people become obsessive, compiling statistics that don’t reflect a program’s impact on their business. Many also confuse analytics with business metrics. Analytics are helpful for optimizing a particular process, like your natural search engine ranking or how to find influencers in communities, but they will rarely tell you anything about the impact of a program on your company’s bottom line and future health.

Some companies measure the wrong things. In one particular case, a company set up a community whose members would communicate with one another primarily though SMS text messaging and e-mail. What did it measure to track its progress and success? Time spent on the site and page views—even though the whole effort could be successful even if people never went to the site. Needless to say, that community never became a mainstream marketing program and was eventually shut down.

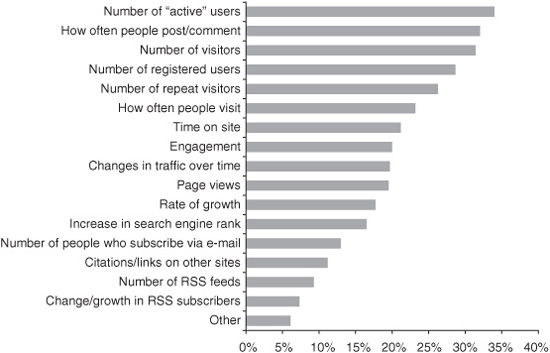

When we conducted the Tribalization of Business Study, we found another anomaly in how people measure progress and success for their Hyper-Social activities. The study found, as shown in Figure 11-2, that the top five analytics being tracked are the number of

Figure 11-2 Analytics Used to Measure Community Success

“active” users (34 percent), how often people post and comment (32 percent), number of visitors (31 percent), number of registered users (29 percent), and number of repeat visitors (26 percent).

Not surprisingly, the same study found that the biggest reported obstacle to success was getting people to engage and participate (30 percent). While it is inevitable that larger communities will end up with 1 percent of their members being very active users who provide enough value for the 9 percent of somewhat active users, who together provide enough value for the 90 percent of lurkers, the largest form of participation in online communities happens to be active lurking. Active lurkers, who may make up 40 to 50 percent2 of your community membership, are those who may take something from the community and pass it along to others using different channels, so they end up contributing to your word of mouth.

Active lurkers also include those people who visit a customer support community and find a solution to their problem without contributing to the community. Those people derive a lot of value from that community interaction, and so does your company, since they do not clog up your customer call center. Active lurkers also include those who will contact the original poster through a different channel, such as telephone, e-mail, or perhaps a face-to-face meeting, in effect continuing the conversation outside of the visible public side of the community, but not outside of the community itself. Fortunately, we found that 18 percent of the companies that participated in the 2009 Tribalization of Business Study are starting to track “lurker” metrics. It’s not easy to measure the impact of active lurkers, but without some sort of measure of their activity, you could miss a lot of the value that they bring to your Hyper-Social processes—especially in a world in which the customer lifetime value is directly proportional to word-of-mouth activities.

Much of the reasoning that leads people to worry about participation levels comes from years of thinking in terms of company- and product-centricity. People look for signs of customer engagement with their brand, their product, and now their communities and other Hyper-Social programs. They have a hard time letting go of that worldview and replacing it with a human- and customer-centric worldview.

Because communities do not align properly with organizational lines or business processes, you should also, wherever possible, measure the indirect effects of your Hyper-Social programs—for example, the impact of your customer service community on your new product development process. Not only will people who participate in your customer service community give you new product ideas, but research has shown3 that informal knowledge-sharing environments like online communities will in fact improve the effectiveness of your formal organizational processes. For example, a sales-driven customer feedback community might improve the efficiency of your formal customer service escalation process as well as that of your formal product definition process.

If we could develop new Hyper-Social metrics, what would they look like? Some of the newer metrics that are already being bandied around could actually be considered Hyper-Social.

Don Peppers, the coauthor of Return on Customer and Rules to Break and Laws to Follow, talks about return on customer, a metric based on customer equity. Don’s take, supported by research,4 is that not all customers are created equal and that we should focus on retaining the ones we have and attracting those with the highest potential customer lifetime value.

Retaining the customers we have is what most customer loyalty programs are focused on. Increasing customer loyalty can have tremendous benefits. When we spoke with Mark Colombo, the senior vice president for digital access marketing at FedEx, he told us that for every percentage point that the company improves its loyalty score, it adds about $100 million to the bottom line. Loyalty is important because as customers stay longer, they tend to buy more, require less help, and pay higher prices. Conceivably they also spread more buzz on your behalf, bringing in more customers through their positive word of mouth.

As we have seen earlier, the customers with the highest lifetime value potential are not necessarily those who convert to customers as a result of your traditional marketing programs. Their total lifetime value also has to include the significant percentage of additional business that will come in because of their positive word of mouth. Don Peppers also reinforced the need to consider customer referrals when calculating customer lifetime value, and he mentioned research pointing to the fact that your highest spenders are not necessarily those who buzz the most about you: “I saw an academic study recently5 about customer referral value being separated out of customer lifetime value. What’s interesting about the study was that these academics found that the highest spenders are often not the same as the highest referrers. A lot of times the customers who refer the most business to you are not spending as much. And if you don’t try to at least understand the value of their referrals, you may not be treating those customers with the kid gloves that they deserve.” In defining return on customer, and in favoring it over return on investment (ROI), Don argues that the number of customers you can have is finite, or, to use economic jargon, customers are the scarcity. Investments, on the other hand are plentiful, as you can always get more.

ROI is a poor indicator for measuring anything that is customer-related. Let’s apply the concept of ROI to marketing programs to illustrate our point. Assume that you have a new product version, for which you develop a special upgrade price and an extra sales incentive. Let’s further assume that you have done well in the past and therefore enjoy some positive word of mouth in the marketplace. You now decide to launch this product upgrade with a massive e-mail campaign and by participating in an industry trade show. What does the ROI on the e-mail campaign tell you about the efficacy of e-mail marketing in this case?

Answer: nothing!

The e-mail campaign could bomb because you could have the wrong offer for that audience, or because you have a sales incentive that competes with a better one, causing the channel to push an alternative product. You could have had a few of your products explode a few weeks before the campaign (it happens; remember the exploding computer batteries),6 resulting in negative word of mouth. Or you could get 30 percent of the good leads that both read the e-mail and went to your show. How do you then determine ROI? And assuming that you can, what does it tell you?

Nothing! With so many variables, you cannot accurately predict the behavior of the whole system that is in play during a launch by understanding the individual parts. Also, the system exhibits emergent behavior, which cannot easily be measured with standard ROI metrics. Let’s assume that you could find a method of measuring ROI that takes into account all of the interdependencies and variables that rule your market at this particular point in time. What would it tell you about the future performance of your marketing programs, incentives, and promotional pricing schemes?

Nothing! Because ROI is a trailing indicator, not a leading indicator.

John Hagel, a renowned business thinker, author, and the co-chair of the Center of the Edge at Deloitte, also takes umbrage with the traditional ROI. Rather than looking for the standard return on investment, he prefers instead to focus on return on information—a leading indicator. You measure this ROI both from your company’s point of view and from the customer’s point of view. As John says: “From a company perspective, the question becomes: How much effort and cost did I invest in acquiring information about an individual participant and how much value have I been able to generate in return, both for the participant and for me? From a customer perspective, the key question is: How much information about myself and my needs have I provided, how much effort did it require and, relative to both of these, how much value have I received in return from the information provided?”

You could, of course, extend this concept to also measure the amount of information you would need to provide a prospective buyer to induce her to make a buying decision. Two other leading indicators that John introduces are return on attention and return on skill set (the latter should really be return on talent, but return on skill set is preferable, since ROT is such an unfortunate acronym).

While many of those metrics are steps in the right direction (they are much more customer-centric than many of the older metrics, and they are also leading indicators instead of trailing indicators), they still suffer from some degree of company-centricity. They center on the interactions between the customer and the company, and the rich Hyper-Sociality that is part of any buying decision is not embedded in them.

Another interesting metric comes from marketing professor Rob Kozinets, who was also the coauthor of Consumer Tribes.7 When we spoke with Rob, he talked about “share of community time” as a metric.8 The problem with calculating share of community time is that there is a huge spread in the estimates of the number of people that participate in communities—between 100 million and 1 billion.

One of the widely adopted metrics that comes close to measuring what we’re looking for is the Net Promoter Score (NPS), which is also elegant in its simplicity. NPS is based on the assumption that companies have three types of customers: promoters, passives, and detractors. You identify those people by asking them a simple question: “How likely is it that you would you recommend [Company X] to a friend or colleague?” Those who score 9 or 10 are promoters, those who score 7 or 8 are passives, and the ones who score between 0 and 6 are detractors. The Net Promoter Score is the percentage of promoters minus the percentage of detractors. So in effect the NPS has elements of loyalty, and also indicates the amount of buzzing that customers are likely to be doing on your behalf. While NPS has proved to be a great tool for many companies, it still lacks the ability to let you focus on those tribal groups that really matter. You can correlate NPS with certain aspects of the offering, but it does not give you cause and effect. As Marty St. George, the CMO at JetBlue, reminded us, “It’s not because there is a strong correlation between NPS and on-time arrival that we should rip out the entertainment centers in our planes.”

In a world in which most buying decisions are social decisions based on knowledge flows that happen within our tribes, and in a world in which tribal word of mouth results in much higher customer lifetime value and customer equity than traditional marketing programs, we should be able to map tribal equity and return on knowledge flows. No one will argue that the tribal equity that exists in the Fiskateers community, where people talk about how the community changed their lives, is much higher than the tribal equity that exists in a company’s Facebook group where a majority of the members join because of couponing.

But how do we measure tribal equity?

For starters, let’s look at the field of sociology, where researchers have developed a large body of knowledge concerning social capital in communities—something that is very close to tribal equity.9 The World Bank even developed a toolkit to help measure social capital in communities.10 The problem with those methods is their complexity. If the process of measuring becomes too complex, people will most likely fail to monitor their tribal equity adequately.

We propose two barometers for monitoring the health of your Hyper-Social programs. The first one is the Reciprocity Barometer, which measures the degree of reciprocity that exists among your community members. Just as with NPS, you could periodically gauge your communities with simple member surveys asking the question:11 “Do you expect to give back and help others in the community?” The second one is a Trust Barometer for your Hyper-Social environments. While trust is not part of social capital or tribal equity, it results from it.12 Trust allows knowledge to flow more freely and encourages reciprocity between strangers. A Trust Barometer could be based on a simple survey question like: “Would you base important decisions on advice that you receive from this community?” Losing trust is the last thing you want to have happen in your tribal environments. As with everything else in social spheres, if mistrust takes hold in your community, it will amplify and spread rapidly.

Just like the Net Promoter Score, the two barometers could also be used to develop scorecards: the Net Reciprocity Score and the Net Trust Score. Both of those scores will tell you a lot about the health of your Hyper-Social activities, and together with the Hyper-Social Index, they will give you a good idea of what might happen if your company were to be hit with a crisis. Companies with high HSIs may still suffer from temporary dips in their Net Trust Score or their Net Reciprocity Score, but because of their high HSI, chances are that they will quickly recover.

The ultimate question, in view of this book’s topic, is whether we can turn the business metrics process into a social process. The answer to that question is yes. Many B2B companies have leveraged the wisdom of their collective sales force to forecast sales. Some forward-thinking companies, like Best Buy and Google, are taking this idea a step further and deploying prediction markets to successfully enlist the power of all their employees to predict what will happen—from store opening dates to product introduction successes.

When it comes to measurements, never forget the end goal of all business: to create a customer. Also remember to be practical, first and foremost. As Jeff Hayzlett, the CMO at Kodak, told us: “You know there are some [measurement] tools that you can use … but I’m not a huge, huge believer in them. I think that in your gut, you know what works…. all marketing does exist to drive sales.”

Here are some other questions that you should ask yourself as people report back on their Hyper-Social activities. Do those metrics make sense? Are they in line with what we are trying to achieve? Are they in line with how we measure our business today? Do the metrics tell me anything about the social behavior of my tribes? Are we monitoring trust and reciprocity in everything we do? Are we rewarding people for the right metrics? Are our metrics customer-centric? Do we know where our future business needs to come from? Do we have a handle on the value of our talent in our business? Do we have a handle on the value of our customers in our business? Do we understand the importance of customer and tribal equity for our future?