Few people would argue against the idea that marketing is in need of great change (marketers too, for that matter). Not only are the things it used to do no longer working, but they were probably the wrong set of things to do in the first place. Let’s go back to one of our favorite Peter Drucker1 quotes: “Because the purpose of business is to create a customer, the business enterprise has two—and only two—basic functions: marketing and innovation. Marketing and innovation produce results; all the rest are costs. Marketing is the distinguishing, unique function of the business.”

That boiled-down approach, of course, is not what most marketers have been doing for the past century. Perhaps that is the reason why we should start thinking of marketing as a way for organizations to behave in the marketplace instead of as a department. Knowing that there is little chance that most companies will toss out their marketing departments altogether, the way Ducati2 did, and remain successful, let’s instead focus on what marketing should be in view of its business purpose: creating a customer and keeping that customer for as long as possible.

Looking at this simple definition through our Hyper-Social lens, creating a customer can happen in multiple ways—the old way and the way it should have been happening all along. In the old days, we would define a market segment based on people’s individual characteristics. We marketers would then target them and interrupt them with information blasts about our products and our brands. Next, we would isolate them from their tribes so that the information that they had about us came only from us, and we would work hard to inhibit them from talking to any other vendors. John Hagel calls these the three I’s of marketing: interrupt, isolate, and inhibit.

As marketers, we never recognized that the buying process is an inherently social process that is influenced by our tribes and our status within them. Marketers never tried to communicate with their customers in a way that was reciprocal, instead just bombarding them with (sometimes useless) information through mass channels of communication. The 4P’s of marketing placed all aspects of the offering (product, place, price, and promotion) squarely at the center of all marketers’ programs. We developed militaristic marketing approaches: fighting the battle for the mind,3 targeting niche markets, outflanking competitors, and developing go-to-market strategies and campaigns. Everything became hierarchical and operationalized to the point where marketing became like finance—interchangeable from one industry to the next.

Now that our customers can be Hyper-Social, those old ways of doing things no longer work. Our customers and prospects reject and mistrust the information coming directly from our companies, and they make buying decisions based on online user reviews and knowledge-based conversations within their tribes that don’t involve us. Some still want to talk with us—but in a meaningful and reciprocal way, and in their social context.

John Hagel suggested an alternative approach to the three I’s of marketing, one that involves the three A’s of marketing: attract, assist, and affiliate.4 In order to attract prospects, we have to find ways to add value to their knowledge-based conversations. We need to assist both existing customers and prospects by making ourselves findable and by being helpful. And wherever possible, we have to affiliate with other solutions providers to satisfy the customer’s real needs, not our need for sales revenue. We believe that maybe there is a fourth A for marketers, that of being the passionate advocate for the customer within our company. Instead of thinking of the CMO as the chief brand advocate in the marketplace, we should think of the CMO as the chief customer advocate, who represents the voice of the customer at the executive table. Let the customers be the product and brand advocates within their tribes—that makes for a nice reciprocal relationship.

Let’s now take a closer look at the different parts of marketing through our Hyper-Social lens and see what happens.

We’re not suggesting that you should do away with brand messaging and positioning altogether, since you cannot control it anyway. People need to know what bucket to put your offering in, and if they can’t figure it out, they won’t know how to assign value to what you have to offer. TiVo ended up in that pickle, with consumers not being quite sure what category of products TiVo occupied. Was it more like a DVD player, or was it more like a computer?

Rock-solid positioning will still affect your revenue and your profits. It’s important to realize that you still have a seat at the customer’s decision-making table—it’s just a much more crowded table, and the size of your seat has been significantly reduced. You need to develop a point of view about your positioning and try to get your tribe to accept it voluntarily. As in most social interactions, your chances of getting someone to adopt your point of view are going to increase if you involve him early on. The more say you give him in the process of cocreating your products and services, and the earlier you get him involved (preferably at the product concept stage), the more he will embrace a shared view of the brand and the product positioning. An added benefit of cocreating products with your customers is that those who are involved in the design of new products will typically pay higher prices for those products.

Marketing executives have come to understand, sometimes the hard way, that brand perception is only as good as the last interaction that the customer had with the brand. When we spoke with Mark Colombo, senior vice president of digital access marketing at FedEx, he described the challenge as follows: “In the 50s and 60s, brands used to be built on a set of attributes. Now brands are built by customers, one experience at a time, and those experiences are, obviously, more and more often online experiences.” You cannot just convey a brand’s promise or a product’s positioning through advertising and packaging anymore; you also need to deliver against that promise across all your other customer touch points, and at any time. That idea becomes especially challenging when you have complex product distribution channels, high numbers of people involved in your service delivery, or a high level of interaction between your customers and your customer service and support center. And remember, even if you are a B2B company, most of those touch points are staffed by humans. This is further complicated by user-generated touch points that people will encounter, such as online reviews, blogs, and online communities. All those touch points can make or break your brand, product, or service promise and position. Like many other things in marketing, this idea is not something new; it’s just that we used to get away with problems in this area because our customers, prospects, and detractors could not behave Hyper-Socially and hold us accountable for our actions.

The way you control a brand promise through multiple touch points is not with the elaborate process manuals that we have grown accustomed to in business. The way to do it is by embracing Hyper-Sociality and all the messiness that comes with it, and allowing all the people involved in the process to behave like humans. Some companies, such as Zappos and JetBlue, achieve this through a shared values-based culture that creates a common sense of belonging among their employees. Others, like Western Union, achieve it by becoming customer-centric to a fault. Still others, like IBM, are doing it by encouraging all of their employees to set up communities with whomever they want, wherever they want, and about anything they want.

The key to success is to embrace all four tenets of Hyper-Sociality: think tribes, knowledge networks, customer-centricity, and willingness to accept some of the messiness that comes with Hyper-Sociality.

“Where are my leads, and why am I getting crappy leads from my marketing department?” If you have been anywhere near the intersection of sales and marketing recently, these are questions that you have probably heard—perhaps many times over. Many senior sales executives are still looking for a predictable flow of leads at the end of a lead acquisition and nurturing “funnel.” And while many marketers have been struggling with setting expectations for predictable lead delivery for more than a decade, their sense of panic and angst about this issue has risen to alarming levels.

So what’s going on?

For starters, the funnel metaphor is broken. People no longer make buying decisions in a linear fashion, going from awareness, to familiarity, to consideration, evaluation, and purchase (or perhaps they never did). Second, people are now turning to their peers, friends, and other users of a particular product for advice instead of to the company. Third, the potential number of choices that prospects can have in their product consideration set is much larger than it has ever been before, and the information sources through which those products can become part of buyers’ consideration sets has grown exponentially as well.

So how should you think differently about lead generation?

First off, ditch the funnel concept, and educate sales on why the funnel no longer works. It’s neat to think of our buying process as a linear and rational process, and in the corporate world, this concept has certainly paid its dues as a reliable sales and marketing management tool. The problem is that we don’t buy that way—the actual process is much more social and much messier. We buy because we bought the same thing before and it feels right, we buy because the purchase is going to make us look intelligent or help us snare a better mate, we buy to increase our status, or we buy for no good reason and make up a rationally acceptable story after the fact. We try to eliminate choices from our consideration set as quickly as possible and for seemingly random reasons. And for some products, we gladly switch our consideration set at the point of purchase. Our buying decisions are emotional ones. Now, that does not look like a funnel—does it?

In a Hyper-Social world, people don’t want to be sold to. They prefer to make their buying decisions as part of a social process (even if they make decisions all by themselves), and they want the company to be involved only at the last minute, when they think they are ready to buy.

That does not take away the need for the company to become part of the buyer’s consideration set. However, since that set will be heavily influenced by Hyper-Social activities and touch points that are out of your control, you will need to think differently about lead-generation activities and in some cases let go of traditional ways of creating leads.

So how do you increase your chances of becoming part of a prospect’s consideration set? You can use traditional marketing programs, such as advertising, direct mail, e-mail marketing, and event marketing, to increase your chances of being noticed by potential customers and their tribal mates. You can also opt to take a more Hyper-Social approach and fuel the word of mouth that happens naturally within your customer tribes by designing the information about your offerings so that it can easily become part of their knowledge conversations, and by knowing where and when those conversations take place.

The good news for marketers who want to follow this path is that most buyers leave a digital trail as they move through their buying journey. When they ask friends on Twitter, you can see it. If they ask peers in communities, you can find it. And when they read or contribute to online reviews, you can get alerts on it. By engaging with your tribes through relevant content at the right times and in the right places, you may actually find that they will grant you a seat at their table. In order for that to happen, though, you need to be Hyper-Social—to act as humans who are part of those tribes and not corporate spokespeople, be willing to help members even if that means recommending things that are not part of your company’s offerings, and listen more than you talk. You want to make customers’ buying journey and all the social contraptions that surround that process as smooth as possible—and since people are self-herding, you want to give them reasons to switch to your offerings rather than stay with the one that they are familiar with.

One of the authors of this book used this method to set up a hugely successful lead-generation program for a large technology vendor. We found that the people we wanted to engage with were especially active on Twitter, so we hired two people with relevant domain expertise. Our two hires were clearly identifying themselves as representatives of our client and started to be generally helpful to prospects who were looking for help. They would point them to valuable resources, sometimes on the client’s Web site or community, and sometimes on competing sites. Within two months, both of them had hundreds of followers, and the program became the most successful lead-generation program that our client had seen for that product line.

If you are still on the fence in terms of whether to engage directly with your tribes and thereby amplify word of mouth or to continue using more traditional marketing programs, let’s review some other evidence that may sway your vote. Research has shown5 that people who become customers as a result of positive word of mouth have twice the lifetime value of customers who become customers because of traditional marketing programs. They also bring in twice the number of new customers because of their word-of-mouth activity than the ones who were sold to.

How is that for a no-brainer?

Now, if you decide to leverage communities as part of your word-of-mouth efforts, which our Tribalization of Business Study shows is being done by more than 40 percent of companies that leverage online communities, you also have to prepare yourself for some counterintuitive consequences. Another research project6 found that while the overall sales of products and services increase in communities, the leaders of your online communities may actually buy less from you. Sure enough, the main culprits here are again Human 1.0 reasons, not Web 2.0 reasons. Researchers found that the people with the highest status within the communities bought less because purchasing did not add to their status anymore—they felt at ease with their status. People who had less status, on the other hand, bought more, and the buying decisions of people with no status were not influenced by the community one way or the other.

Another counterintuitive aspect of increasing word of mouth is that the impact of that increased chatter on sales will be greater if it comes from your nonloyals rather than from your most loyal customers. It’s also worth noting that the same research project7 that came to that conclusion found that while the biggest buzzers among your most loyal customers are the opinion leaders, that is not the case among your nonloyals.

Finally, we could not have a section on lead generation without talking about search engine marketing or search engine optimization techniques to improve the relevance of your content in natural searches. These techniques allow you to deliver information in an ambient and contextual way when the prospect is searching for information about products and services. It’s the low-hanging fruit that should be part of any comprehensive marketing plan. Unfortunately, the increasing competition for keywords may eventually result in decreasing returns for this method as well, so marketers shouldn’t get complacent and come to rely exclusively on search marketing for lead generation.

Another low-hanging fruit that is not always used effectively is to proactively engage with customers about new products and services when they interact with you through your customer service and support center. But please don’t give your service reps incentives to start selling product. Train them instead to ask how people use your product and see if they can perhaps suggest better alternatives, and above all, let them be Hyper-Social when they have the customer at the other end of the line. You’ll see: amazing things can and will happen in Hyper-Social environments.

Setting up a page or buying banners on Facebook or MySpace may seem like a good idea because of the targeting capabilities—and some will see it as a way to become Hyper-Social. In reality, you will find that most people will not befriend a brand’s fan page unless there is some serious incentive or heavy couponing associated with it. So while it taps into a Human 1.0 trait, it’s hardly a Hyper-Social one. Discounts and coupons affect the pleasure side of our brain, the part that gets addicted to things and constantly needs more of them in order to derive the same pleasure. These incentives destroy revenue and profitability for all the players in the long run.

Even though advertising is not a marketing process, but an activity in support of various marketing processes (awareness creation, lead generation, brand positioning, and so on), it is important enough to merit its own section in this chapter. Considering the budgets that companies are allocating to advertising, it’s important to understand how fundamental market changes will affect the role of advertising in the future marketing mix.

Let’s first take a look at advertising through the Hyper-Social lens. Most advertising is focused not on tribes, but on market segments. When it does focus on tribes, as much of the MINI Cooper advertising does, it strengthens the link between the social activity that happens in those tribes and the brand itself.

Most advertising is channel-focused, meant to reach a mass audience through mass channels of communication. Sometimes it is focused on the networks that matter, though, and when that happens, ads go viral. A good example of that is the Dove Evolution ad, targeted at normal-looking women rather than models, which got 44,000 views in its first day, 1,700,000 views in its first month, and 12,000,000 views in its first year. Many ads are product-or brand-centric, touting the features and benefits of particular brands and products. Some are human-centric, and even reciprocal—think of the ones that entertain and make you laugh. The problem is that we often forget the brands that brought us these entertaining ads.

This brings us to one of the underlying drivers that will change the face of advertising in the future: people have limited attention, and they are increasingly tuning out brands and products. In fact, all the drivers that allowed advertising to work are undergoing deep transformations. First, the number of media outlets available to advertisers is exploding. Next, an increasing number of products are vying for our attention—which is limited and which we can increasingly direct toward where we want it. Last, the advertisers themselves are getting fed up with the diminishing returns of eyeball-based advertising. When enough companies shift from paying for impressions and click-throughs to paying for engagement, which some companies have signaled they will do, the whole eyeball-based business model that sustained traditional media will start falling apart. Underlying most of these tectonic shifts is Hyper-Sociality at work.

Moving forward, what do you think advertisers will do? The early signs of where they will focus their attention and assign their budgets are already here. Some, like Kodak, will rally around product placement on popular TV shows like The Apprentice. Others will extend the product placement concept to online social games, like Farmville or Mafia Wars. While doing so may deliver great results in the short term, especially for the game producers, saturation of product messages will inevitably reach its peak, and people will once again tune out the brand messages. Almost all companies will try to capitalize on the psychological “halo” effect—a Human 1.0 bias in which we project certain characteristics from a particular situation onto the evaluation of other traits of a person or brand. So if companies allow us to do good and to feel good in the context of their brand, we will automatically extend that feeling to the brand. Most corporate social responsibility programs are the result of companies trying to capitalize on that halo effect.

Some brands take this idea one step further and integrate their programs with social networks or let you participate in their socially feel-good, do-good programs. Kellogg brought its Kellogg Cares social responsibility program, focused on relieving hunger in America, to Facebook in the hope that members would join its cause—and they did, to the tune of more than 200,000 members. American Express, through its Members Project,8 is turning part of its charitable program into a Hyper-Social process by allowing people to submit their causes and letting others vote on which ones Amex should fund. While there is plenty of research to show that people will switch to socially responsible brands and buzz about them more than others, we predict that this too will have short-lived marketing results. As more and more brands become socially responsible, making this switch will become a norm for doing business, much like product quality, and not a competitive differentiator.

Still other brands are resorting to crowdsourcing their advertising to their user base. A successful example of that concept is the network Current TV, which turned it into a semisocial process by allowing its audiences to create and vote for viewer-created ad messages (VCAMs) on behalf of its advertisers. While the use of this model may reduce the cost of ad creation and increase the likelihood that ads are more customer-centric, the end result is still eyeball-based, a broken business model.

We need a fundamental shift in how we think about engaging customers and prospects. Engagement needs to happen in a Hyper-Social context, focused on tribal networks and human-centric to a great degree. Marketers have to move past individual behavioral targeting and instead engage with their customers and prospects based on what they know about them from their social profiles. This process can happen in online customer communities, open e-commerce platforms like Amazon, or social applications like the LivingSocial Visual Bookshelf on Facebook.

Realizing that the status quo is a powerful force, and that the technology to give users full control over their social profiles is not quite here yet, we know that these changes will not happen overnight. We are also conscious of Paul Saffo’s rule on change:9 “Change is never linear. Our expectations are linear, but new technologies come in ‘S’ curves, so we routinely overestimate short-term change and underestimate long-term change.” Thus, we believe that the future of advertising in a Hyper-Social world will in fact be far more different from what we can now imagine.

In Chapter 5, we talked about how market research in a Hyper-Social world will need to change, and how the data from our in-house customer relationship management (CRM) systems should be used as part of customer support more than as part of sales. Let’s circle back to this topic and highlight two other issues related to capturing and managing Hyper-Social customers and prospects.

Many industry leaders will argue that the return on investment (ROI) of traditional CRM systems has been dismal at best. Combine that with the fact that the latest economic crisis has rendered much of the data in these systems obsolete (people lost their job, some switched industries, many companies “right-sized,” and so on), and you realize that good ROIs for CRM investments are not on the short-term horizon. What will make a difference is if we can combine our in-house CRM data with our customer and prospect dynamic (not static) social profiles that reside in their communities and tribal hangouts. If we host those communities ourselves, it’s easy to marry the two, but if we don’t, getting to those profiles becomes a whole lot trickier. Either we have to rely on the people who own the community platforms to give us access to those profiles, which could be fraught with complex privacy issues, or we have to wait until the members themselves can control their profiles and decide how much of those profiles to share with us. One way or the other, the future of CRM systems will have to include a social component—some call it social CRM.

Capturing customer social profiles will give us the ability to identify who has the most influence in a community and who has the biggest megaphone. For instance, it’s easy to see, on Twitter, whose announcements are “re-tweeted” by more than 100 people more often than not.

Herein lies a danger, though. The knee-jerk reaction of most marketers will be to give preferential treatment to those people, extending better pricing to the influentials or demonstrating a greater willingness to bend the rules for those with bigger megaphones. Creating special pricing for the influentials is like giving them special leadership status. In the short term, it often leads to solid gains, but in the long run, it could ruin your ability to attract new customers. You see, leadership status is something that humans covet, and when they reach it, they hoard it and sometimes bend the rules to keep it to themselves and away from others, especially newbies. When communities do not refresh their leadership, but, instead, make it hard for new members to become leaders, they start repelling new members. The long-term prognosis for those communities is always the same: a slow but certain death. This is a problem with which all too many online gaming companies are already familiar.

No one will argue that knowing who has the biggest megaphone in social media is not immensely valuable. As Pete Blackshaw, the executive vice president for Nielsen Online Strategic Services, said to us when we spoke with him,10 “The people who typically use the customer service back channels are the same people who tend to use megaphones to express their dissatisfaction. If you do it right you can use that information to develop a so-called user contribution system, where consumers help one another and become advocates for the brand—reducing not only your customer support cost but also other costs like consumer research.” What you cannot do is allow your company to become a hostage of those with the biggest megaphones by showing a higher willingness to bend the rules for them. Marty St. George, the CMO at JetBlue, is very adamant about this point. He told us that catering too much to the most influential users in the community at JetBlue not only would undermine the decisions made by the company’s front-line employees, but could eventually bring down the whole values-based culture that allows the company to be Hyper-Social in the first place.

In case you missed it, traditional media is under siege. As we said in the advertising section, it does not look as if the eyeball-based business will survive Hyper-Sociality. The results so far: 30,000 reporters have left the industry since 2008.11 Combine that statistic with the ongoing increase in people who are vying for the attention of the remaining mainstream media reporters, and you end up with a pretty bleak picture. PR and thought leadership will have to change fundamentally in order to deliver the same results.

Most PR agencies have seen the writing on the wall and have jumped on the social media bandwagon. They will now monitor your online chatter and deal with social media bloggers and influencers the same way they deal with traditional journalists. The problem is that they approach these influencers as representatives of a channel, not as the leaders of their tribes. For most of the PR agencies, social media is not a platform that enables Hyper-Sociality, it’s another channel through which to send free messages to prospects.

In the face of dwindling traditional media outlets, companies like Procter & Gamble, MasterCard,12 Microsoft, IBM, and H&R Block13 are compensating by creating their own media outlets. P&G does it both online and offline with its Rouge magazine,14 while companies like H&R Block and MasterCard set up YouTube channels to run customer contests, generate consumer-generated support tips, or otherwise engage with their audiences. Both Microsoft and IBM created online publications, but with very different approaches.

Unfortunately, most of those initiatives rely on the old media models. They are company-centric information channels focused on specific market segments. Take one retailer as an example. It originally hired a team of frugal moms (there are now more than 20) who normally blog about frugal shopping, and gave them all a free video camera to record video tips on how to shop frugally. Those videos are posted on a YouTube channel, where other frugal shoppers are encouraged to upload their own video clips. Periodically the company gives away one year of free groceries to the producer of the best video clip. Now this makes for a nice marketing program—one that probably does well for the retailer.

If the company had decided to take a more Hyper-Social approach however, it may have ended up with a movement that no one could stop. It could have augmented its YouTube channel with a Twitterlike system to allow people to post their frugal finds in real time. Along the way, the company would have enabled these moms to establish status within their tribes through the number of their followers, thereby inspiring a competitive streak and probably better “content” as a result of their individual efforts to get more followers. In a tribal environment like that, you would not even need monetary rewards—the program would work on reciprocity, the glue of Hyper-Sociality.

Sony took a different approach. The company recruited a number of dads to form the DigiDads.15 The site describes the program as follows: “Each participant will receive various Sony products on loan and will be given different assignments that capture their family experiences using the products.” In a lot of ways, this approach is not all that different from sending sample products to review editors at mainstream media publications. But here again, while Sony may have ended up with a nice marketing program, it could have tapped into the Hyper-Social nature of its buyers. Some of these blogger-dads may be the leaders of real tribes (their families), but they are not leaders of consumer electronics enthusiasts’ tribes. And even if Sony had identified the right tribal leaders, it did not to provide a place for these tribes to engage and form stronger social bonds in the context of its products, the way Jeep did with its online and offline communities. Instead of approaching the program with a PR mindset, the company could have taken a more Hyper-Social course.

The difference between Microsoft’s approach and that of IBM, which we described in Chapter 4, lies again in the Hyper-Social approach. IBM created the Internet Evolution online magazine16 the same way you would create a mainstream media property. Microsoft, on the other hand, took a more Hyper-Social17 approach. It set up its FASTforward thought leadership blog, focused the blog on the Enterprise 2.0 tribe (people who are passionately convinced that Web 2.0 tools within the enterprise will forever change the way we work), and recruited the leaders of that tribe to develop original content for the community instead of traditional reporters.

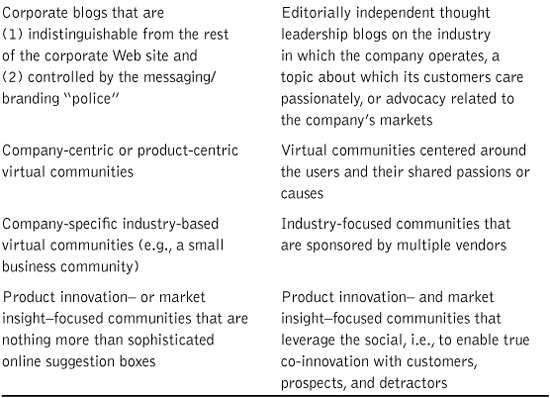

A majority of the Marketing 2.0 efforts that we are seeing today are timid attempts to leverage Hyper-Sociality. More often than not, they are extensions of what companies already do today. Table 14-1 gives some examples of what we are likely to see in the short term, and what could happen if those same companies were to fully understand Hyper-Sociality.

When designing social media–based marketing programs, companies have to make sure not to think of them as timid, bolt-on

Table 14-1 Potential Marketing Shifts Driven by Hyper-Sociality

programs, but instead think about how to turn traditional marketing processes into socially enabled processes.

Other than customer service, marketing is probably the part of your business that is most affected by the Hyper-Social shift. It is likely that Hyper-Sociality has already invaded all aspects of your marketing activities—whether you like it or not. Hopefully your leadership team is not resisting this shift, as doing so would be futile. If you want to challenge the thinking of your team and help steer it in the right direction, make sure to ask the following questions when you review marketing plans.

Why are we still wasting so much money on advertising? How has the efficacy of our lead-generation programs changed over time? Are we thinking about all the customer touch points when we talk about brand management? How are we amplifying word of mouth? Are we having success? Are our customers embracing our position, or is there a disconnect between what we think we stand for and how they perceive us? Are we getting our customers involved in our marketing activities? Do we understand how people make buying decisions for our products, or are we hanging on to the old funnel metaphor? Are we getting our customers addicted to coupons and discounts, or are they buying for other reasons? Do we have an idea of how long customers stay with us and why they defect? How are we conducting market research? Does it really tell us something about the future? Have we allowed the Hyper-Social shift to affect how we do PR and thought leadership? Do we have the right customer information in our CRM system?