What is the value of a customer? Customers’ value is multifaceted: They buy products; they may recommend products to other purchasers, serving roles as comarketers and cosalespeople; and they may support your business model by contributing more data, information, or content (as they do with Amazon’s book reviews). Loyal customers may return repeatedly and buy over and over again. With such repeat business, you have to wonder, what attracted them to come back to you in a world that is brimming with other products? Perhaps it was a marketing message that they received or a word-of-mouth recommendation. Perhaps it was a coupon or some other incentive. More likely than not, however, such return business is the result of their enjoying an exemplary customer experience.

Do you know what sort of customer experience your customers are receiving, both from your company and from other people outside your company? And are you ascribing value to your different customers correctly? Customer experience is the internal and specific response that customers have to direct or indirect contact with a company. Direct contact can be with customer service, sales, or some other area of a company. Indirect contact can include recommendations, advertisements, ease of use, and criticisms or reviews that customers see. The sum of these various touch points determines the customer experience, and an enjoyable customer experience can be used to target specific high-potential customers.1

Customer Service 2.0 is customer service that is socially enabled—it’s where people help one another, not where corporate processes simply work toward minimizing the time spent trying to resolve customers’ problems and complaints. To get to Customer Service 2.0, companies first need to fix what Pete Blackshaw, the executive vice president of digital strategic services at Nielsen Online, calls the great “conversational divide” that exists between marketing and customer service. Blackshaw believes that it is unfortunate that customer service is so frequently considered a nonstrategic part of the business, so that there is little integration among what companies know about their customers from their CRM systems, their social media strategies, the promises they make through marketing, and what actually happens in their customer service departments when service representatives talk with customers.

It is curious how many people fail to realize that Customer Service 2.0 is a strategic part of the business, not just a cost center. Customer service is the one place where customers expect companies to participate in the conversation, and by engaging in those conversations, companies have the opportunity to turn customer service into an extension of their sales and marketing efforts.

Just as with marketing, most early attempts at Customer Service 2.0 have been timid and have failed to take full advantage of the true potential of Hyper-Sociality in customer service. Table 15-1 gives some examples of what we are likely to encounter in the short term and what could happen.

As part of the Tribalization of Business Study, we encountered many companies that have begun creating Customer Service 2.0 initiatives. One company whose program is being copied over and over again is Microsoft, which came up with a “Most Valuable Professional” (MVP) program to reward its most helpful customers. The uniqueness of the program is that people get rewarded for their past performance, not future expectations. In fact, there are

Table 15-1 Potential Customer Service Shifts Driven by Hyper-Sociality

no expectations of MVPs in the customer support communities. Because the MVPs have in essence already shown their inclination and ability to help others, they don’t need to be encouraged to do so in the future. The MVPs have self-selected themselves as helpers, and there is no requirement that they continue to do so in the future. Programs run by other organizations have set future requirements, which has led people to become competitive and to engage in aggressive tactics to become higher rated.

As we’ve said before, it is amazing how few companies consider their customer support and customer service a strategic part of the business. An informal poll that we conducted among 50 companies found that almost none of them was thinking of making social media investments in customer service.

It makes you wonder, “What are they thinking?”

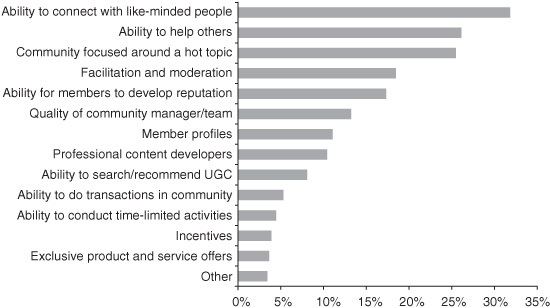

Customer service is a perfect area for companies to use social media and to leverage Hyper-Sociality. After all, most people do love helping other people. Plus, it’s a given that at some point in the customer life cycle, most people do need help. And when people need help, they prefer to get it from other people rather than from organizations. In fact, one of the interesting “unexpected learnings” that we uncovered while conducting our yearly Tribalization of Business Study, in which we interviewed more than 500 companies on how they leverage online communities as part of their business, is this: people actually want to help companies and one another. This reciprocity ranked second among those features that, when included in a community, contributed most to the effectiveness of the community (see Figure 15-1).

It is also ironic how many companies do not consider customer service a strategic part of their business when you realize that the

Figure 15.1 Community Features that Contribute Most to Effectiveness

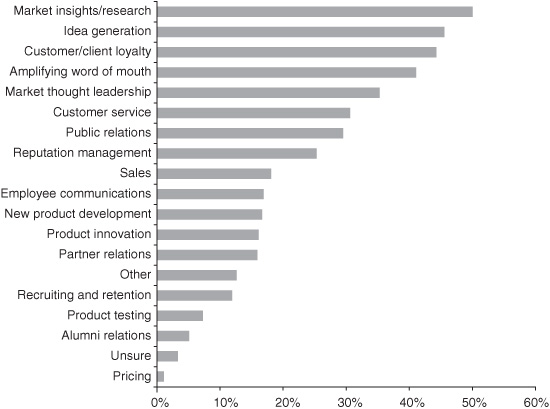

Figure 15-2 Top Five Purposes of Online Communities

biggest brand damage often occurs as the result of a poor customer service experience. Indeed, as shown in Figure 15-2, customer service was ranked sixth in the top purposes of online communities. If companies are, as they universally claim, truly focused on pleasing the customer, then customer service should be at the very top of the list.

Trying to assess how Hyper-Sociality might affect your customer service can be scary. Just ask yourself this question: What happens when nobody calls my help desk anymore? That question should prompt a series of increasingly disturbing questions: Where are customers going to get their support? What happens if they get bad advice? Am I liable if a misused product ends up injuring someone? Don’t I need to protect my organization’s investment in branding and product development by ensuring corporate customer service?

As we discussed in Chapter 3, Hyper-Sociality will eventually invade all aspects of customer service. It will not happen overnight, but it will happen, whether you like it or not. The drive for people to help one another is just too powerful a social force to stop. Just take a look at the popularity of social Q&As,2 which have become the highest-trafficked areas not only on sites like Yahoo! and Linked in, but also on commercial sites like CarSpace. Or visit customer support boards like Dell’s or Microsoft’s, where you will find people helping others who seem to be putting in the hours of a full-time job—except that they are not getting paid for their efforts.3 As we said before, the drive to help one another is caused by a reciprocity reflex—and once people realize that they can do so on a large scale, they will.

Smart businesspeople will see this trend as a positive one and tap the power of Hyper-Sociality through online communities to increase the effectiveness of their customer service departments while decreasing their costs. Visionary business leaders, on the other hand, will go a step beyond this and turn their customer service department into a revenue source rather than a cost center. These leaders are the ones who recognize that customer service is actually one of the most logical points at which to enter the most important conversations that are happening in their marketplace—those that happen between their customers. They will turn their customer service department into an extension of their marketing and sales departments, or, like Zappos, they will turn it into their sales and marketing department by empowering the customer care team to suggest alternative products. And just like TiVo or Ducati before them, they may also find their most promising new product innovation ideas that way.

Note that leveraging Hyper-Sociality in customer service is not the same as crowdsourcing your customer support activities. In some rare cases, there may be enough passion around your offering or a critical mass of users of your products to allow you to crowdsource customer service. In most cases, however, your support activities will remain at the center of the customer service community and will be amplified by that community, not replaced. Microsoft may be able to turn every single one of its support articles into a wiki and expect decent results from cocreating those support articles with its users. For most companies with fewer users, however, this could end up in disaster, with tons of inaccuracies, stale articles, or, worse, content that could expose you to liability. This is especially true in rapidly evolving markets where products are constantly being updated or upgraded, and where product variations introduce new customer support opportunities.

More so than for any other department within your company, taking advantage of Hyper-Sociality in customer support requires that your organization be allowed to behave in a Hyper-Social manner as well. If you truly want to support your customers, you need to empower your employees to engage those people where they are already gathering, and where they will be gathering next month. Sometimes that is at your organization’s site, sometimes it is all over the place, and sometimes it’s at a focused destination that you did not set up. The reason that this is so important is twofold: (1) people will seek help with your products from others in a variety of places, not just your customer support community, and (2) people want to be helped by people, not by faceless organizations.

While it may seem obvious that customers would seek support for your products in your customer support community, in reality, they will look for it across a multitude of sites. That is especially true for products that have complex distribution channels. When you have a problem with your shiny new Canon lens, do you look for help on Canon.com, Bestbuy.com, Amazon.com, or GetSatisfaction.com? Or do you turn to your independent photography enthusiast community, or maybe a photography Facebook group that you belong to? Such was the case with TiVo, where users set up a vibrant TiVo customer support community and ran it independently from the company. TiVo did not try to set up its own customer community and lure people away, which many companies might have attempted to do for the sake of controllable knowledge management—i.e., access to people’s profiles, ability to mine the content, ability to generate reports, and so on. Instead, it engaged people where they were already hanging out, and turned the existing community into a real competitive advantage.4

Another company that allows its organization to behave Hyper-Socially in order to provide better customer support is Best Buy. An employee developed a very simple social media monitoring tool, called Spy,5 that can easily be configured by any individual within or outside of the company. Spy scours the Internet in real time, looking for the terms that the user has defined—perhaps about a product, or perhaps about the company itself. Spy has no workflow system in the background to dictate what information is important or to whom it must be reported, nor does Spy produce the sophisticated reports that you can bring to your staff meeting every week. Instead, managers encourage employees to download the little application, monitor what they think is important, and engage where appropriate and without embarrassing the company. This program has been hugely successful in fostering awareness of the conversations about the company that are taking place. Best Buy realized that in order to take advantage of Hyper-Sociality in customer support, you need to behave Hyper-Socially yourself. Best Buy has since increased its commitment to Hyper-Social customer support by introducing Twelpforce on Twitter, where volunteers and Best Buy employees alike answer users’ calls for help.

We are probably witnessing a change in mindset among customers as well, with customers’ first thought being to reach for a search engine or social media tool and look for DIY solutions to their problem with a product. As a result of the increasing willingness of customers to get involved in problem solving, figuring out Customer Support 2.0 should be top of mind for all companies. The increasing tendency of products and services to have a software component, often updated remotely by the seller (consider MP3 players, GPS devices, and consumer software), will additionally contribute to the expectation of continuing and proactive after-sales care.

Organizations can take a number of actions to begin moving toward Hyper-Social customer service. First, all departments where the customer may go with complaints or questions—and these include sales, product development, and marketing—should be included in the information flow. All of the employees in these departments should be allowed to listen and to go where they need to go, both online and within the company, in order to engage in conversations with consumers. Super-users among the tribes should be cultivated, and resources should be devoted to the Customer Service 2.0 initiative so that content is curated to the extent possible. Super-users probably have important insights into how products and services can be improved, and hold positions of authority with their tribes, so their insights need to be communicated both internally and externally. Adding social Q&A functionality is likely to be well received, and customer service should determine whether customer experience goals, including customer satisfaction, repeat sales, and referrals, are being realized, and what sort of course corrections are warranted by the user feedback. Customer service should also be primarily responsible for making sure that findings are circulated to all stakeholders, and that return on investment (ROI) calculations are both appropriate and circulated to the appropriate decision makers (lest the initiative be shut down because of inadequate returns). For instance, if more loyal customers are being created through Hyper-Social customer service, a value should be ascribed to this enhanced loyalty, and then it should be communicated in terms of ROI.

Management must be thoughtful and innovative about incentives and metrics when it comes to customer care. Too many companies seem to develop metrics that encourage customers to leave the site or get off the phone as quickly as possible. Similarly, using “time on site” or highest number of page views (which we have seen companies measure in the Tribalization of Business Study) as a metric in the customer care realm is probably inappropriate as well. When Customer Care 2.0 becomes Hyper-Socialized, it will include employees outside of the formal customer care group. A salesperson, for instance, might find herself jumping into a conversation with a customer who is having trouble, and given her deep product knowledge and passion, she will probably be able to develop solutions to the customer’s concerns. But if one of those solutions is a used or refurbished product with lower profit margins or a lower price point, will the salesperson be put in the position of pitting her financial performance against what is best for the customer? Has the company properly aligned her goals and incentives so that she doesn’t feel conflicted about suggesting the lower-priced used product, or does the company instead demand that she reach a certain sales quota? Properly thinking through scenarios like this will be a critical process for companies that wish to manage the transition to Hyper-Social customer service successfully.

The best way to attract and retain customers in an increasingly noisy and competitive world is probably to be as helpful as possible, both before and after the purchase. This implies an emerging requirement for customer care people in your company: to enable greater flows of knowledge between your customers and all of the people who can help them with their problems. Implementing social Q&A features, like those mentioned previously, is a strong step in the right direction. You will also have to develop platforms of resources, people, and institutions that are preidentified and accessible to your customers so that they can get more value from your products and services than from those of your competitors.6 The SAP Developer Network, where SAP users can gather to ask questions and help others, is one such example. This Hyper-Social customer care platform is so effective that the average response time for posted questions is about 17 minutes, and about 84 percent of the problems raised are resolved.

When the company has structured its systems to support Hyper-Social customer service, it can work beautifully, as Ram Menon of TIBCO recently told us:

Well, the first thing we did is create a dedicated community for our customers where they had all those things: they had friends, they could post confidential information, they could share information.

... We had this large travel firm post an issue with their production implementation of TIBCO. Normally if they called us for support, they would call tech support and the kind of support we provide costs us $1,000 a call. And within 20 minutes another architect at a big financial services’ firm actually told him how to solve it and sent him a piece of code on this behind-the-moat kind of website.

So, the thing you learn from that is, you created a community and the community helped each other and saved us money, but at the same time provided a positive experience for people within the TIBCO system to work with each other.”7

Other companies, such as Kodak, report monitoring Twitter and then disseminating the top 20 or 30 complaints that crop up to different points in the company on a daily basis.8 Mark Colombo, senior vice president of digital access marketing at FedEx, noted to us recently that using a listening platform that permits the company to immediately engage online with people who are having problems is having a profound impact on customer loyalty. Indeed, Colombo says that customers who have had a problem resolved to their satisfaction are actually more loyal than consumers who have never had a problem!

And when someone does have a negative experience, we can jump into that post that is going on, and offer that customer support and help, where we can actually turn someone from being a negative word-of-mouth into positive word-of-mouth marketing. And what we have found, even on our loyalty work, customers who’ve never experienced a problem have lower loyalty than customers who experienced a problem that was resolved to their satisfaction.9

Colombo explained that FedEx’s research indicated that optimizing key “customer touch points” contributed to loyalty. These touch points include a combination of brand and transactional experiences. FedEx data show that every point by which the company can improve its loyalty score translates into about $100 million added to the bottom line.10 Moreover, Colombo notes that his research shows that if you try to solve people’s problems, and you can’t, as long as you were fair in trying to do so, the customer will continue using your services and promoting the company.11

Clearly there is an enormous opportunity for Hyper-Social companies to manage the customer relationship better. Indeed, customer relationship management (CRM) systems are the organization’s attempt to develop a memory of its customers—to become more Hyper-Social. The customers already have a memory—indeed, they will recall past misdeeds and punish corporations for not doing what they consider to be fair.

It’s important that you develop an accurate picture of your customer and develop better rapport with that customer in order to enhance the customer’s true lifetime value. As some commentators note, customers are becoming the scarce resource in today’s world, because of the plethora of products and services available on a global level.12 The balance of power has shifted from the producer to the customer. As a result, you will need to leverage every touch point with that customer to ensure a superior customer experience, and to tap into both that customer’s value as a buyer today and tomorrow and that customer’s role as an advocate and an unpaid sales agent.

In a Hyper-Social world, your present and future customers interact with your organization in countless new ways. They are likely to be discussing your products and services on many different blogs, enthusiast Web sites, and social networks. They are evaluating your marketing promises, what your products actually provide, and how your organization resolves the differences between the promises and what was delivered. The tool that companies mainly use today to manage customer interactions is their CRM system. But is your CRM tool capturing only purchasers’ information, direct touch points, and complaint info? Does it help you develop more trust in your company within your customer? Does the tool include insight into where the customers came from—word of mouth, marketing campaign, or referrals? Does your system include information about what each person is saying about your company, brands, and products, and does it include information about what he’s saying about your company on social media? Does it capture information on whether that person is a super-user, or otherwise helpful to other customers? And is the information being used to better help the customer? Or is the new information being used in an organizational system of sales rewards and measurements that were better suited for a previous era and are dangerously out of synch with present Hyper-Social customer care expectations?