Market insights/research (50 percent cited this as a top five purpose of their online community)

Market insights/research (50 percent cited this as a top five purpose of their online community)The cofounder of Sun Microsystems, Bill Joy, has been quoted as saying that there are always more smart people outside your company than within it. With the Hyper-Social shift that we are witnessing right now, it’s important to know that those smart people outside your company can help you design and develop your company’s latest products and services.

Some of the most immediate and exciting applications of how Hyper-Sociality can change your company are in the areas of product development and innovation. Indeed, there has been a significant amount of recent experimentation in this realm, and the astute businessperson need not look far to see how his peers are using tribes to improve, reconfigure, or completely replace product development and innovation. The actual tactics used span a wide spectrum, from users innovating new features to people outside the company being paid to solve thorny problems, to companies receiving virtually all their product ideas from people outside the company. And it’s not only products that we see tribes influencing—business models are also being improved by opening up corporate processes to the tribes and socializing these processes. Companies are using Hyper-Social innovation to improve product development, business models, and corporate processes.

Let’s look first at how Hyper-Sociality is affecting product development. Intuitively, businesspeople know that successful product development, and creating innovative goods and services for the customer, is one of the core goals of most companies. Products that the user desires and that are differentiated from those offered by the competition drive profits and pricing power. Few people want to sell a commodity, a me-too product that is distinguished only by price. Any manager worth her salt wants to develop the new mousetrap for which the world will clamor, and to have the associated pricing power.

Unfortunately, successful product development in the conventional sense has proved to be notoriously difficult to get right. The majority of new products that are introduced fail, and those that work tend not to be followed up effectively with similar hits. And, for the reasons explored by Clay Christensen in his series of books on disruption theory, companies’ incentive plans, corporate structure, and product development and introduction processes are geared more toward regularly giving present consumers “improved” products that are designed more to support existing profitable businesses than to provide customers with what they truly want.

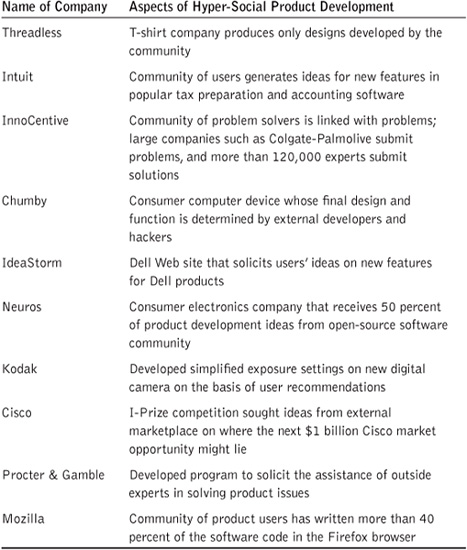

The Hyper-Social shift promises to dramatically reform product development in fundamental ways. First, there are new inputs to consider. Product development today is often an insular process of passing best estimates of customer desires through a proprietary corporate process of determining what can be provided profitably and in conformance with distribution, competitive, regulatory, and strategic constraints. R&D and marketing typically are part of the product development process, and a snapshot of customer demand is periodically checked to see how the new product comports with that screen shot of customer demand. Depending on the competitive nature of the industry and the products that are being created, the specifics of product development vary widely. As Table 17-1 details, however, companies in most industries that have been socializing the product development process have met with great success.

As these companies show, the social humans who are the target consumers of your products and services often are very happy to participate in product development (or to “cocreate”), and can be quite good at it. What we see from the marketplace, however, is that companies are following more of a gradual approach toward tribe-based product development. When we surveyed hundreds of companies for our 2009 Tribalization of Business Study, we found that the top five corporate purposes of online communities were

Market insights/research (50 percent cited this as a top five purpose of their online community)

Market insights/research (50 percent cited this as a top five purpose of their online community)

Idea generation (46 percent cited this as a top five purpose of their online community)

Idea generation (46 percent cited this as a top five purpose of their online community)

Customer/client loyalty (44 percent cited this as a top five purpose of their online community)

Customer/client loyalty (44 percent cited this as a top five purpose of their online community)

Table 17-1 Examples of Hyper-Social Product Development

Amplifying word of mouth (42 percent cited this as a top five purpose of their online community)

Amplifying word of mouth (42 percent cited this as a top five purpose of their online community)

Market thought leadership (35 percent cited this as a top five purpose of their online community)

Market thought leadership (35 percent cited this as a top five purpose of their online community)

Only 17 percent of the companies surveyed cited new product development as a top five purpose of their corporate-sponsored online communities, however. And only 7 percent cited product testing as a top five purpose of their online communities.

We believe there are several reasons for this subordination of product development to more conventional marketing activities in corporate online communities. First, since the marketing function is most likely to be the sponsor of online corporate communities,1 it’s logical that marketing goals would be the primary drivers of those communities. In addition, at this early point in the Hyper-Social shift, companies may be merely porting their prior marketing activities to a new platform—that online place where the tribes are congregating. Many of the executives who are in charge obviously have not made the next conceptual leap to moving product development to the tribes as well. As we discuss in Chapter 10, relinquishing that degree of control to the consumer or to non-customers (and possibly to other functions within the company) frequently challenges management.

Another outcome of product development moving to the tribe is that cycle times are likely to contract sharply, as the community of interested users, fans, and detractors will provide its input immediately and constantly until its comments have been acknowledged (ideally, from the vantage point of the community, by affecting the next iteration of the product or service). Given this dynamic, present product development cycles, which are keyed more to the time of year, what the competition is doing, or technological innovations that enable product innovation, will have to yield to a much better driver: what the customers are asking for in highly visible online forums.

Also, given the networked nature of Hyper-Social product development, companies will need to develop alternative methods for determining when a product is finished or when it is complete. As Susan Lavington, senior vice president of marketing at USA Today, recently told us about the product development process with readers at her newspaper:

We’re in constant evolution. It doesn’t have to be perfect, it doesn’t have to have all the bells and whistles when we launch it and we’re just going to keep working on it and improving it. That’s something that we did embrace in our early years and continue to try to embrace and get to that idea of we’re in “constant beta,” and that’s just the way life is these days.2

Another likely impact on product development will be how companies organize themselves to create new products or enhancements to existing ones. It’s not unimaginable either that in-house R&D or product development will dramatically shrink, or that they will grow to include people with new skill sets. Corporate researchers who formerly spent most of their time researching what the purchaser might want in new products will have new roles as that information is generated in real time through interaction with the tribes. Internal groups that have had the task of forecasting future demand and manufacturing needs would similarly undergo significant change as customer demand becomes increasingly visible and quantifiable.

Yet another change that we can expect in product development will be the emergence of completely new products from perhaps noncommercial locations. Take the open-source phenomenon, for instance, where passionate but unpaid computer programmers write professional-grade software that is then made available for free use and further development by others. Product development may well take place elsewhere (for instance, in the open-source community) and drive immediate and substantial opportunities for your company to develop associated products for markets that someone else has identified and pioneered!

Hyper-Social product development could also serve a critical marketing function, reaching people who are inclined to buy the product or who participated in its creation, and those who became interested in the product through their membership in a tribe. Deloitte’s 2009 State of the Media Democracy Survey indicates that 63 percent of American consumers learned of a new product for the first time while they were online, and 51 percent say that they purchased a product because of an online review. If these people were allowed to participate in the product development process as well, imagine what that could do to improve your commercial prospects. As Barry Judge, CMO of Best Buy, noted in a recent discussion with us, “I think you can really turn consumers on because they’d love to be part of the creation, not just getting feedback on what you created. We have to figure out how to turn that on.”3 Dan Ariely, behavioral economist and author of the book Predictably Irrational, echoes this when he observes that one of the best ways to get more and better ideas from people is to let them see what other people are building on top of their ideas.4

One of the key revelations here, however, is that by adopting a Hyper-Social approach to product development, you are opening product development to smart people everywhere, not just in your company. As prescient executives have noted, no one company will ever employ the majority of the world’s smartest people. Hyper-Social product development won’t be a panacea for everything that ails corporate product development groups, but it could be one of the most potent tools for product development to emerge since disruption theory.

A fair point to raise at this juncture is whether the voice of the communities or the crowd will provide better information, as opposed to just more information. Although we are early in the process of having users materially contribute to product development, and we don’t have a lot of data to rely on, we do see that many of the ideas cannot (for various good reasons) be incorporated into new products. For instance, Caroline Dietz, manager of Dell’s IdeaStorm, notes that product ideas from the online community have to make business sense. “When we’re making decisions on what to do with these ideas, whether or not it plays into our long-term strategy definitely plays a role…. A lot of times there may be something that’s a customer demand, but it may not serve our entire customer population.”5

Another fair issue to flag here is that even though a winning idea may bubble up from the new participants in product development, the size of the market associated with that innovation may not be within the range of potential revenues or profits that the company typically requires. Beth Comstock, GE’s chief marketing officer, recently observed that new product ideas sometimes don’t match up with the size of the opportunity that an organization of GE’s scale requires. Some of these ideas can go on to success, however, if GE attaches them to a larger platform of related products, or if it partners with smaller enterprises that can bring such smaller innovations to market profitably.

Perhaps this portends a new era of partnering between larger and smaller companies, or the emergence of a hybrid model in which a company suggests the basic platform for a new product, based on what can be produced at a certain price point and with a given technological level. Then the crowd will polish it and enhance it with those features and nuances that only a smaller crowd of specialized users would require. And perhaps others will then market the product and continue improving it, leaving manufacturing and distribution to those commercial enterprises that have special expertise or scale advantages in those areas.

In addition, it is arguable that truly breakthrough products cannot be produced effectively through a Hyper-Social committee, so to speak. As Henry Ford wryly noted, if he had given people what they wanted, he wouldn’t have created the automobile; he would have produced a faster horse. But this issue doesn’t point to the failure of Hyper-Socializing product development. Rather, it points to the company acting in a different capacity—as an innovator, rather than as a manufacturer or distributor. Indeed, the rise of Hyper-Social product development is likely to present companies with a critical question that is bound to keep executives busy for the next few years: What business are we in? Are we a product development company, privy to certain little-known technological developments that will enable new products that our customers would never imagine possible, or are we experts at delivering products at the lowest cost? Or are we experts at customer development and customer relationship management, and we will leave product development and manufacturing to others? This atomization of the complex modern corporation, driven by the new lower costs of communication and coordination conferred by digital technologies and the Internet, is an increasingly likely outcome for many companies.

So, it is clear that product development and innovation will be dramatically affected by the Hyper-Social shift. And it is encouraging that some executives, like Kristin Peck, the senior vice president of worldwide strategy and innovation at Pfizer, are asking themselves the right question: “When we thought about innovation, we asked ourselves, ‘how do we make it more social?’” But in addition to changing the structure of the product development team and perhaps the R&D team, what other impacts will making innovation a social process have on the organization and its ability to innovate?

As noted earlier, enabling new innovation processes will spur companies to reconsider exactly what business they are in. For instance, a vendor of witty T-shirts might realize that it’s in the business of product innovation; since it is using crowdsourced designs, it can perfectly predict what its customers want. Why, then, would it continue to produce products, ship them, and handle returns as well? Wouldn’t it be better to offload those functions to someone like Amazon, and focus all its resources on what it does best (assembling and polling its tribes)? This “unbundling” of the corporation is likely to accelerate as various corporate functions become less important or superfluous because of the interaction with tribes.

The changing nature of product development and innovation may well alter other key corporate functions. For instance, in a situation in which the tribes are influencing product design, the organization becomes more of a filter and reality checker (i.e., can that product ever be built profitably?) than a raw innovation house. The firm requires more researchers and more number crunchers to cycle through the possibilities, and fewer creative folks in-house to generate the ideas. It may also require more financial types to position the company with investors and to model capital needs so that it can raise additional funds to bring cocreated products to market.

And if these changes in product innovation occur, will the organization be nimble enough to respond to the collapsed cycle times, negotiate the new codevelopment relationship with its tribes, and make the significant changes in its inventory management and sales channels? The company’s leaders should start thinking about the vested interests of those functions that may be challenged, and what sorts of obstacles they might pose.

Competitively, how will the company capture information and insight before competitors who are lurking in the community are able to appropriate them? How will companies compete on innovation in the future when they are all speaking with, or perhaps cocreating with, the same communities? Developing value propositions and other strategies that attract and retain the most creative tribes will clearly become critical to successful companies.

Companies will also need to avoid thinking that this interaction with passionate cocreators translates only into new product ideas; the interaction might also lead to deeper appreciation of customer frustrations with existing products or corporate processes, culminating in improved customer experiences with the company, its products, and its brands.

Indeed, cocreation can yield many other positive outcomes as well. Not only will products potentially be more aligned with what customers want, but quality can be higher because having more people with a vested interest in the product will ensure that bugs are detected and cured early on and easily. By opening up organizational boundaries and allowing people within the company to interact with people outside of the company, new perspectives and creative juices will begin to flow. New information flows will begin bubbling up between formerly disconnected humans, and teams can begin learning from formerly undiscovered resources, both within and outside the enterprise. These new information flows may create new value for customers or turn into new revenue streams for the company.

As cocreation with noncompany individuals grows, wise managers will give employees greater freedom to self-select the projects that they want to work on. Leaders will also experiment more frequently with new products, services, and processes, running an open laboratory of sorts where the customer is free to experiment and to vote on what the company should tweak or bring to market. Since innovation is more likely when different disciplines are seated at the same problem-solving table, visionary leaders will permit formerly separate groups and tribes to work on the same project and problems, eroding corporate silos, which are more suited to the slow-moving marketplaces of yore. Historically powerful corporate groups that are intent on maintaining the status quo will be kept at bay by those forward-thinking leaders who look to customers and prediction markets as arbiters of what the company should be creating or selling. Managers will realize that they are in fact now managing for creativity, not trying to manage creativity.

Vibrant cocreation with the customer, and the emergence of volunteers who provide invaluable insight into how to improve product and service offerings, will ultimately affect the culture of the company. That much-sought-after human-centricity that we discuss in Chapter 6 stands a much greater chance of taking root and flourishing within this sort of corporate culture as management and employees begin to see the virtuous cycle that can be created by an engaged customer sharing value with a Hyper-Social company.

Hyper-Sociality provides an elegant solution to Bill Joy’s insightful observation that “there are always more smart people outside your company than within it.” By leveraging your organization’s tribes, you may improve and spur product development and innovation. The increased cocreation with customers and business partners may itself lead to business model innovations, and to the organization’s realization that it should focus on certain activities and disengage from others. Is your organization taking the necessary steps to permit Hyper-Social product development and innovation? Is it listening to the tribes and giving them the tools, information, and feedback needed for effective innovation? Is your organization anticipating internal conflicts that might arise as a result of Hyper-Social innovation, and developing systems that reward both employees and customers for participating in Product Development 2.0? Who will own these jointly created products, and what will your organization’s core business look like five years from now?