Given the discussion up to this point about Hyper-Sociality, and about how important social interaction is to humans, it shouldn’t be surprising that “human capital,” the people who actually make up companies, is increasingly crucial to the proper functioning of the organization. Indeed, CEOs and other top executives routinely and regularly remind us that their people are their top priority, the chief reason that their companies have been successful, and that people are the only assets that really matter. And deep down, we all know that this is true—buildings, products, and patents are not the assets that directly generate value. These assets might appear to be the drivers of revenue and success, but all of them are abstractions of human intellect, creativity, and collaboration. They are the artifacts that humans leave behind when they’re done creating. Through various proportions of inspiration, perspiration, and dedication, humans create things and information that they and others can use, or put to work.

But if you’ve watched organizations at work for the past 100 years or so, they seem to have forgotten these apparently self-evident truths. We saw recently that in the face of a global recession, one of the first ways in which companies cut costs was by thinning the human ranks. It is curious, and telling, that the cost-reduction lever that is pulled first is often the one attached to human capital. If companies still haven’t grasped the importance of their human assets, the Hyper-Social shift will bring it to the forefront. As a company undergoes the Hyper-Social shift, the abilities and activities of its human capital need to change as well. In many cases, companies also need to readjust their view of what skills and talents their employees should possess, how they should ideally manage those employees, and how they can recruit and develop those employees more effectively. In addition, managers must become more aware of how their internal talent management philosophy will need to evolve in order to mesh with the increased Hyper-Sociality that is sweeping over the marketplace.

Prevailing in the race for the talent that will excel in the coming Hyper-Social economy requires the engagement of not only the human resources department, but the entire leadership team. This is because effective reengineering of talent will require a rewrite of many of the firm’s operations, structures, and strategies. Indeed, commentators have stressed the need for taking a new view of talent in this emerging networked, dynamic, and increasingly social economy.1 As leaders begin to prepare for the shift to Hyper-Sociality, they must consider whether employees with skills that were developed and selected 10 years ago will be able to interact with users in real time, communicating transparently and authentically, using new social media tools. Do these employees have the depth of knowledge about all of the company’s offerings, and how these might be tailored and delivered to delight a vocal tribe of customers that may stretch around the globe? Are these employees sufficiently trained in what they can bind the corporation to, and aware of where in the company they need to go to convey customer insights and find what they need to develop adequate responses to the demands they are seeing from the market? Are they passionate about the products that they produce and the people who consume them? An organization’s answers to these questions will indicate how closely its human capital philosophy is aligned with the evolving Hyper-Social shift.

Indeed, Susan Lavington, senior vice president of marketing at USA Today, cited some of these challenges in a recent conversation with us:

And I empathize with them [USA Today’s journalists] when they’ve been asked to keep up what they’re doing in print, but now have this really 24/7 community that they are in charge of and people want to talk to them on a regular basis and curate and bring content in and point out the latest happenings…. They’re passionate about their beats, they’re passionate about the content that they create. So, finding other people who are passionate about it too has been very rewarding for them.2

As information technology becomes increasingly ingrained in corporate functions, it will become harder for rigid, rules-based software systems to react to unexpected, human-driven exceptions to what the programmers anticipated. How many existing customer relationship management, supply-chain, or pricing systems were designed to react to customers by providing real-time feedback? How many of these systems’ designers even contemplated allowing users to access them from different departments, silos, or business units (as will surely be the case in a Hyper-Social company)? One way of improving the flexibility of installed IT systems has been to overlay social networking technologies that permit humans to respond to these unanticipated events and to share best practices on how salient information can still be captured in the installed, existing IT systems.3

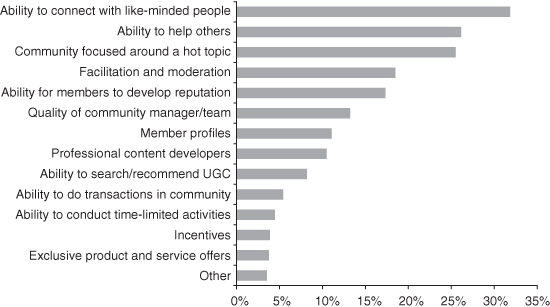

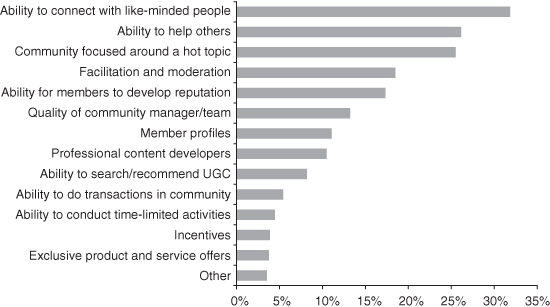

Our Tribalization of Business Study indicates that the traits of those humans who are interfacing between companies and their tribes are critical to the effectiveness and success of these communities. Indeed the quality of the “facilitation and moderation” and the “quality of community manager/team” were cited as numbers four and six, respectively, of the factors contributing most

Figure 18-1 Community Features that Contribute Most to Effectiveness

to community effectiveness as can be seen in Figure 18-1. These factors placed higher, in fact, than incentives or exclusive product and service offers!

Because of their typical command-and-control legacy, many businesses today are expert at disseminating information, policies, and communications downward. Where they are more challenged, however, is in moving information from the rank and file upward, or moving information sideways between different groups or silos. Indeed, suggestion boxes, peer reviews, 360-degree reviews, and anonymous reporting hotlines are all different means of moving information in a fashion that from the corporate perspective is unnatural. No formal mechanisms previously existed to move information upward or sideways—these fixes had to be created to move information in previously unimaginable ways. Communication channels, both formal and informal, have long existed in organizations, but they are likely to see dramatic changes in the near future. As social media become more entrenched, talent will begin to collaborate socially and based on skills, rather than by top-down mandate or within the traditional boundaries of the corporate world.

Since a large part of talent management involves identifying and building on skills and improving weaknesses, Hyper-Sociality will dramatically improve companies’ talent development. Best practices will be better shared, high performers will be able to teach others, nodes of excellence will be easier to identify, and the tendency to hoard knowledge or expertise will be counteracted by the human bias toward reciprocity.

For instance, IBM has developed an internal employee directory called “BluePages” that permits the matching of people looking for career advice with other IBM employees who have the required knowledge or experience. The Web-based system attracted more than 3,000 employees in less than two months, and permits global employees to “see” fellow employee profiles across the entire IBM organization to find advice on everything from promotions to how to innovate.4

Another example of the way Hyper-Sociality is changing talent management is the appearance of tools such as Rypple at companies ranging from software developers to restaurant chains. Rypple permits employees and bosses alike to post 140-character requests for feedback on their performance (“How was my presentation this morning?”), and to quickly see a composite of all anonymized responses from their colleagues.5

Other factors are at work in bringing greater Hyper-Sociality to talent management. One key driver is the increased use of quantitative methods to determine the specific value that individual workers deliver to the corporate bottom line. Building on the analytic rigor already employed by the finance and operations functions, where every asset or process is carefully evaluated, human resource professionals are beginning to assign value to people within an organization. Various systems are used to study corporate communications systems and networks to determine which employees seem to produce valuable contributions, are cited most by other employees, have been most successful in the past, or share common attributes with other identified high performers.

Where individual employees rank in this analysis could be used to determine who gets raises and who gets laid off. Although this might appear Orwellian, it is interesting that the software algorithms closely mimic very human-sounding ways of assessing another person’s value as a team member. Indeed, it’s arguable whether such a transparent system based on member input would provoke a Hyper-Social backlash.

Moreover, as Jeff Howe notes in his book Crowdsourcing, the community is extraordinarily good at gauging the output of other community members and identifying talent,6 and this could reduce the all-too-common example of the terrible employee who, through flattery, office politics, or managerial inattention, rises within the organization. Such careless advancement of unqualified employees could be sharply reduced by the community’s vigilant analysis.

These new systems for using social data to determine the value of employees can also be used to retain employees. One such system creates profiles of good employees who have left in the past, indicating what their skills, relationships, and educations looked like. The system then identifies similar employees who might be at risk of leaving the company.

The Hyper-Social shift will have a profound impact on how talent is recruited into (and sometimes alongside of) companies in the future, and how the firm retains that talent. Given the fact that many companies court volunteers who are technically not employees to assist the companies in reaching their business goals, perhaps “recruiting” needs to be expanded from its conventional sense of applying only to employees to include other people who help the company achieve its business goals (regardless of whether they are employed by the company). But before we look any further at these changes, let’s look at the state of recruiting today.

In contemporary service and information companies, human capital is arguably the enterprise’s most important asset. When knowledge is the key input, and the massaging of information is the key process of an enterprise, buildings, production lines, and physical inventories become less important than human intellect and talent. This alone is a challenging shift from the past, when monolithic, hard-to-replicate fixed assets were often the most important to an organization. It is also a stark shift from when employers recruited people to do specific, well-defined tasks that persisted relatively unchanged over time. Today’s employees need to evolve as technology and the competitive environment change rapidly. Indeed, given this need to be chameleonlike in what one can do and what one’s skills are, it’s not surprising that one of the key aspects that workers today look for in their employment is the ability to develop their skills and talents.

Indeed, commentators like John Hagel, John Seely Brown, and Lang Davison point out that

Compensation and benefits packages are surely important. But the opportunity to develop professionally consistently outranks money in surveys of employee satisfaction. Only by helping employees build their skills and capabilities can companies hope to attract and retain them. Talented workers join companies and stay there because they believe they’ll learn faster and better than they would at other employers.7

Consider the backdrop against which this recruiting reality exists. Cultural changes over the past 30 years have given employees the freedom to job-hop without recrimination, and new technologies have freed people to work anywhere and to expand the set of potential employers for which they can work. The rise of double-income marriages provides either spouse with an income-generating safety net of sorts that enables him or her to leave an undesirable job.

As tribes exert increased influence on companies and drive change across enterprises, from product offerings to marketing practices to organizational structures, recruiting individuals who are able to navigate these shifting tides will become top of mind for corporate leaders. But today’s companies aren’t structured or habituated to encourage workers to develop the new skills and capabilities that they desire. Many companies may have formal training programs, but few have the flexibility or structures necessary to make workers feel that they are learning and developing faster than they could elsewhere. Because of siloed organizational structures and inflexible internal policies, workers are often specifically limited in terms of which information and resources they can access, and which other humans they can collaborate with. Given management’s realization that good product development ideas may well come from outside the organization, it is probably only a matter of time before more companies rethink their policies to allow employees to reach outside of the enterprise and to collaborate with others (regardless of their employment status).8 Such a shift will likely require management’s reassessment of what sort of training and education employees will need to understand what proprietary knowledge and information should stay inside the organization, and what should be more freely shared.

Therefore, organizations that give workers the ability to alter processes so that they can solve problems and provide value more effectively in a Hyper-Social world will stand a greater chance of retaining those employees and attracting more like them. Companies that permit employees to self-select tribes that they would like to work with internally on projects are likely to appeal to Human 1.0 traits, and increase the satisfaction and performance of those employees. Much as companies need to learn to listen to their Hyper-Social customers, they need to recognize that their present employees are either attracting or repelling future recruits by what they say and do regarding their employer. Giving present employees the freedom, tools, and guidance to ensure their continual improvement is truly a win-win proposition from a recruiting perspective; it just remains to be seen how many companies are able to reconfigure their internal policies and habits to foster this sort of employee development.

As John Hagel noted in a recent discussion with us, this desire of employees to be challenged and to develop may have profound implications for corporate strategies going forward. Since it stands to reason that workers will develop fastest in companies that are growing the fastest, companies that pursue slow-growth strategies will find themselves at a competitive disadvantage when it comes to attracting the right talent.

I would argue that training programs at best are maybe 10% of the talent development opportunity, that most of the talent development occurs in the day-to-day job environment, work environment. Your challenge as an executive is to figure out how you can reconfigure that work environment to develop talent much more rapidly.

Ultimately you’ll have to rethink strategy. One example is if you are really committed to talent development, you have to pursue a high-growth strategy. If you are pursuing a low-growth strategy, you will not develop your talent as rapidly as people who pursue high-growth strategies.

So, it’s important to shift your focus on the strategy dimension, how you organize the company and how you define and execute the operations of the company. If you do talent development as your key priority, all of that starts to change.9

Another recruiting disruption that is being driven by the Hyper-Social shift is the increased ability to work with volunteers in a fashion that is tantamount to their being employees. Perhaps recruiting is an imprecise term for this emerging practice, but there is clearly an opportunity to use tribes to recruit supporters and helpers who want to help, but who don’t want to be full employees.10

Recruiting professionals within organizations will also need to recognize that because of the increased and ongoing communication with Hyper-Social stakeholders, a company’s recruiting is likely to become more of a continuous conversation, not just an episodic event driven by an open position. How will your organization match existing talents and emerging needs faster than your competitors? Are you working with the various business functions to anticipate the skills you will need? Are you opening up the process of developing job descriptions more widely, making it more of a social process where future colleagues are given the opportunity to weigh in on needed skills and what the role entails? Given that more than 30 percent of the companies we studied in the Tribalization of Business Study use only a part-time person to manage their online communities (arguably the most Hyper-Social job in any company today), we suspect that comprehensive descriptions of the type of employees that are needed to moderate online communities, for instance, are nonexistent in the majority of firms.

Notwithstanding these compelling reasons for using a more Hyper-Social mindset for recruiting thinking, only 23 percent of the companies surveyed by Deloitte in the 2009 Ethics & Workplace Survey used social networking for recruiting purposes. Our 2009 Tribalization of Business Survey found that only 13 percent of the more than 400 companies polled ranked “recruiting and retention” in the top five purposes of their online communities, and that human resources was involved in the creation of corporate communities only about 6 percent of the time.

There is emerging scientific research that indicates how a Hyper-Social organization should manage talent, and it not only provides management with significant insight into how employees should be managed for optimal performance, but also sheds light on how external groups (such as tribes) may react to an organization’s policies and actions. As David Rock notes in “Managing with the Brain in Mind,” “Although a job is often regarded as a purely economic transaction, in which people exchange their labor for financial compensation, the brain experiences the workplace first and foremost as a social system.”11 Using functional magnetic resonance imaging scans of human brains and other tools, researchers have recently conducted a significant amount of analysis into how humans’ ingrained social nature affects how they perform at work and how they respond to managers’ and coworkers’ actions.

Rock has put together an acronym, SCARF, that captures those factors that affect humans the most in the workplace: status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness, and fairness. Simply put, any workplace developments that reduce an employee’s status in the workplace, certainty, autonomy, relatedness to those around him, or sense that the organization is fair will cause him to exhibit a threat response. This threat response is expressed differently in different individuals, but it typically includes feelings of distress that impair analysis, creativity, and problem solving.12 In essence, the threat response impairs the skills most important to knowledge workers and those dealing with a dynamic environment.

This brain research is important because it provides a scientific rationale for the Hyper-Social nature that we see humans exhibit, and because it demonstrates that the brain is really a social organ that is deeply affected by social interaction. Using these new tools, we can see the actual physical impact that social interaction, positive and negative, has on the brain and on our resulting behaviors.

Looking at these five SCARF factors that are critical to human happiness in the workplace, we can see how Hyper-Social companies should best interact with their Human 1.0 employees and tribes. Why do people contribute their valuable time and effort to developing open-source software or writing product reviews? Perhaps because it raises their status with others in the tribe. Why do people form tribes? Maybe it is because the other members of their tribe are humans with whom they feel a high degree of relatedness. Why do talented employees seek out one another across organizational silos and self-assemble into teams for certain projects? Because it allows them to exercise autonomy, which, in simple terms, makes their brains feel good.

Unfortunately, most organizations still consider their talent rational, economic beings who can be motivated by pay, bonuses, and policies. How likely is your organization to use scientific research like this to structure jobs and reward systems, and to acknowledge the social aspect of workplace dynamics? How likely is your organization to use these principles when dealing with your tribes? Which one of your competitors will begin to do so before you do?

In order to become more Hyper-Social, companies will increasingly need to recruit, retain, and develop employees who can consistently apply the Four Pillars of Hyper-Sociality. Those employees who prove to be especially adept at managing a Hyper-Social business will be in great demand, and will enjoy great power in relation to the companies that are trying to recruit them. Will your organization be able to move beyond outmoded practices that view employees as interchangeable cogs, and begin identifying and retaining those employees that permit your organization to excel in a Hyper-Social marketplace? What is your organization doing to identify these sorts of employees, and what is it doing to learn from them? Is your organization allowing these talented employees to choose the projects and teams for which they have an affinity, and ensuring that they continue to develop so that they don’t go to greener pastures? Has your organization realized that employees view their work experiences through a social lens, and that workplace policies that undermine employees’ status, autonomy, and feelings of fairness have dramatic physical impacts on them?