The Night Raid

Suddenly, what had previously been a vague concern of grown-ups had become a matter of vital interest of his own, and a tragedy that was to befall a people had become Sunil’s own personal pain. How could his uncle be so callous, so oblivious of what was real, even when facts were pushed right under his nose? Matt the Prof had been right all along, he saw that clearly now. Busy people like his Uncle Vish didn’t understand the forest, or the tigers that lived there, or the Baigas. His short encounter with them had shown him how happy they were in their forest. Jungu, who was only a girl, was quite fearless in the forest, because that was her home. She knew more about plants, which one would heal a wound and which one would cure a fever, than grown-ups from the city. It was just not right that the Baigas should be told to clear out of their forest, their home. No one had the right to make them leave. It was no use saying, well, that was how grown-ups thought. He would be a grown-up one day but, he decided, he would not think like Uncle Vish. He would do what was right by the Baigas, by his little Jungu. Yes, but by then they would all be gone and Jungu would have been made into a servant, ordered about by fat men sitting smugly in chairs in dirty offices. He choked at the thought, and started coughing, so he had to get out of bed and drink some water.

Sleep would not come easily but gradually, despite all he was suffering in his head, he dozed off fitfully, the pain in his heart worse than any he had suffered in his knee. In any case the golden stars and silver moon of his coverlet had once again formed a ring round his wound and were curing him better than any stupid ointment out of that stupid first-aid box. He had fallen into a deep restful sleep when the stars rose from his knee and gathering in front of his eyes blazed forth so brightly that he woke up with a start. Jungu’s face was pressed against the windowpane, and when she saw he was awake, she beckoned him to get up and come out. He dressed hurriedly, pulled on thick socks, his walking shoes and a sweater, and slipped out as quietly as he could. He looked at the luminous dial of his watch. It was just past one o’clock in the dead of night. Jungu had already gone to the edge of the clearing round the dak bungalow and he could dimly see her figure waiting impatiently for him.

She ran on ahead towards the long road leading to the jungle and then jumped into the low ditch that ran parallel to it on one side. He slid in without much difficulty, his knee feeling perfectly okay, he noticed with surprise.

‘Jungu, why are we in the ditch?’ he whispered.

‘We do not want to be seen, that’s why,’ she said. ‘Come on, let’s go as fast as your leg can carry you.’

‘Oh, it is all right. Thank you for curing me,’ he said a little self-consciously.

She didn’t answer but ran on in a crouch, looking watchfully in every direction like a little animal, he thought. He followed as best he could, as noiselessly as he could manage until they stopped under the shelter of some trees.

‘You remember those bad men we saw near the nullah?’

she asked. He nodded. ‘Your uncle’s jeep had been there before.’

‘My uncle’s jeep? How do you know?’ he asked confused.

‘There’s a cut in one of the rear tyres. I had seen that mark in the wet mud there. But I was too frightened then to understand,’ she said gravely. There was a flash of fire in her eyes.

‘You? Scared?…’ he started.

‘No, not for myself,’ she said quickly, ‘but for you. If they had seen you they would have kidnapped you – or worse!’

A chill shot through his body at the thought. ‘But what has my uncle’s jeep got to do with them?’ he persisted.

She turned to look at him, and he saw she looked quite grown up in that moment.

‘Someone in your uncle’s camp goes to meet them. We are going to find out. Come, but remember the path we are taking. That’s important!’

With that they stole through the forest, she leading the way and Sunil reconciling himself to following her every signal while trying to remember the route, as she had instructed him to. She stopped many times, ever watchful, and studied the ground carefully, before deciding on a path. They went through the densest undergrowth but he did not hesitate even for a second for he knew that it would be safe wherever she led him.

Finally, they got to the nullah where she had met the bad men. She bent to study the mud in the pale moonlight that filtered through from above and nodded.

‘That jeep has come here again tonight. See! The track in the wet mud is still fresh,’ she pointed out in a whisper. ‘We have to be really careful. People don’t walk through here, not even us Baigas, for tigers like to keep cool here and don’t want to be disturbed. Come.’

Sunil had no wish to disturb sleepy tigers either, then or ever, but Jungu was already well on her way, bent almost double, so he simply followed. They soon clambered up out of the nullah and forced their way through the brush. Soon, the trees had thinned out into a clearing and Jungu quickly pushed him down into the grass. Th en, both of them on their hands and knees crept forward slowly till Sunil was peering down from behind a rock at an old deserted Gond village.

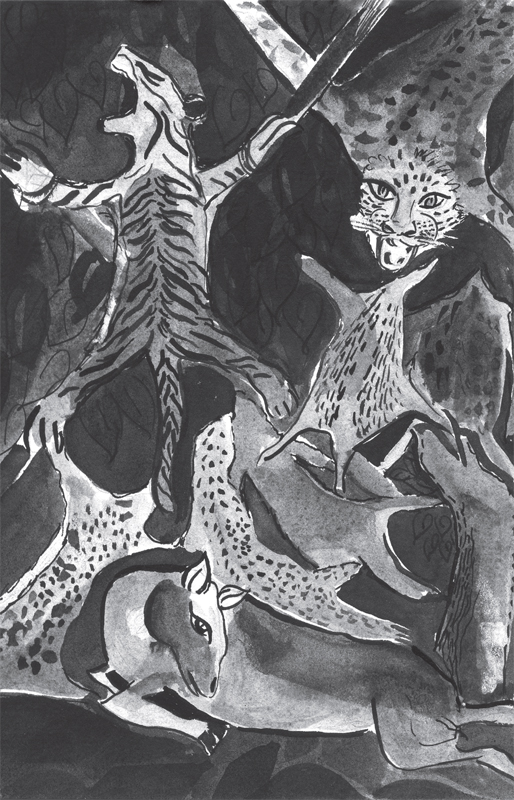

The roofs were all long gone but there was smoke and light coming from a campfire and they both heard drunken laughter. Jungu beckoned to him silently and they circled round behind the rocks to get a better view. Suddenly, they caught a terrible stench and in moments they were able to tell why. A tiger had been killed and hung

up between two crisscrossed poles, blood still dripping from its open jaws. There were skins of all sorts stretched out around it – deer skins in plenty, a leopard skin with the head still attached, a butchered nilgai, the flesh of which was being cooked by the rascals. They could see the jeep parked under a distant tree.

Jungu put her lips close to his ear till he tingled with the sensation. ‘You must go back and get your uncle. Veyne! Go quickly now!’

Sunil understood what he needed to do. He hesitated for a moment about leaving her alone and then said to himself she was the mistress of the jungle and a priestess and no harm could come to her. He wriggled off quietly at first and then after he had put a distance between himself and the poachers’ camp, he set off at a dogged run, skirting the nullah where tigers liked to cool off and keeping to the ground where he could see what he was stepping on. It was close to 3:30 early in the morning when he sighted the dark long dak bungalow with all its lights out. He ran ahead noisily and banged on Uncle Vish’s bedroom door.

Panting, and in between gulps of water, he told Uncle Vish, Mr. Dubey and Matt the Prof what he and Jungu had done and what they had seen. A policeman had come to Uncle Vish’s bedroom by then and after a short low conversation, Mr. Dubey turned back looking very serious.

‘I am afraid, Sir, the boy is telling at least part of the truth. The jeep is missing. No doubt the rascal who drove off thought he would get back before we are up. My orderly has gone to get Motu who undoubtedly knows something. We will find out soon enough.’

In a few minutes Motu appeared, with a long woollen cap pulled over his head and shivering inside a dirty shawl, more from fear than the cold. Mr. Dubey planted himself in front of the cook and fired a few straight questions.

Motu looked around miserably. ‘What can I do, Sahib? I am just a cook, not even from this terrible place, but from Khandwa. I get to see my mother once a year, for just two weeks! What can I do?’ he wailed.

‘No one is asking you to do anything. Just tell us now all that you know. Now!’ Mr. Dubey was most compelling.

‘Big people do whatever they like, but I am a small man, what can I do? I should not even know what they are doing,’ he whimpered. Mr. Dubey impatiently caught him by the arm, dragged him outside and after commanding him in low firm tones, came back a few minutes later, looking even more determined. He said something to Uncle Vish and then said loudly, ‘I am afraid the fellow is a much greater rascal than I had thought.’

They quickly made preparations to leave. Sunil hobbled out on to the verandah, pulling on his sweater. Uncle Vish turned to Sunil with some concern. ‘What, young man, you must be quite tired after your night-time adventure, I think you should stay back and rest your leg.’

Sunil shook his head determinedly. He felt fine, he said, miraculously refreshed. Matt the Prof pressed his shoulder with great understanding and gave him a confidential wink. The party set off at a steady pace through the night, Sunil noticing that the two policemen now carried rifles at the ready. He wasn’t as careful going to the poachers’ hideout as Jungu had been when they first set out for he knew the rascals would all be at their camp, most probably drunk and dead to the world. When they got near the camp though, he signalled that they should go forward as silently as possible. Near the rocks, they circled around as before but this time there were much louder bursts of drunken laughter and raucous hoots and someone was pleading that they should be careful.

When he peeped over, Sunil’s heart almost stopped for he saw a dreadful sight. Jungu was in the grip of a large fat man whose back was turned to Sunil. In front was the man in dhoti he had seen two days before.

‘Remember, she is a witch, a Baiga witch,’ warned the dhoti-clad man. ‘No good will come to us from harming her! No good comes from even touching her!’

Every drunken poacher roared with laughter, the fat man most of all. ‘What can she do, she is dead meat!’ he roared. ‘Yes, perhaps, we will eat the little witch! They say that if you eat a witch she cannot harm you. Shall we eat her?’

They all roared approval while the dhoti-clad man danced in futile anguish.

‘Coming too close to the camp once too oft en was your mistake, witch,’ said the fat man gleefully twisting Jungu’s arm till she cried out sharply in pain.

‘And catching hold of her was your first and last mistake, Chamanlal Singh,’ said Mr. Dubey in a cold clear voice. ‘If one of you makes any move, I will shoot you all dead!’

The camp fell silent all of a sudden. Chamanlal Singh, the fat Forest Ranger, turned around slowly and faced Mr. Dubey whose drawn revolver was pointed unwaveringly at his head. Chamanlal dropped Jungu’s arm and slowly, and slowly raised both his hands above his head. All the other poachers got up unsteadily to their feet and also put up their hands. The two policemen then went forward at a word from Mr. Dubey to handcuff the men, and it was all over very soon.

Even as Uncle Vish, Mr. Dubey and Matt the Prof were going round gloomily inspecting the poachers’ camp, Sunil turned to Jungu and apologized.

‘Jungu, I should never have left you. I am sorry I came too late,’ he mumbled.

She looked him straight in the eye and smiled. ‘No, you came just in time. I knew you would.’