In February 1775, when the Assembly refused to choose delegates for a Second Continental Congress, the authority of New York’s legal government collapsed. The Committee of Sixty, assuming quasi-governmental power, called for a public meeting at the Exchange in early March to devise a plan for choosing a congressional delegation. To ensure a strong patriot turnout, the Sons of Liberty rallied at the liberty pole on the appointed day, then marched downtown in force, “round all the docks and wharves, with trumpets blowing, fifes playing, drums beating, and colours flying.” The excited crowd that followed them to the Exchange endorsed the Sixty’s proposal that the selection of delegates be entrusted to a special provincial convention of representatives from every county in the colony, to convene at the Exchange six weeks later. Governor Colden talked about preventing the meeting by proclamation, but neither he nor the Assembly had the nerve to do so—which made the royal government look even more ineffectual. New York’s Provincial Convention met on April 20 and put together a congressional delegation. The old Assembly adjourned, never to meet again.

Three days later the city learned that Gage’s redcoats had been bested by mere militia at Lexington and Concord. Isaac Sears, John Lamb, and Marinus Willett quickly gathered a crowd and headed for the East River docks, where they emptied two ships of provisions intended for the British forces. Willett then led a second raid on the City Hall arsenal, removing nearly six hundred muskets, bayonets, and cartridge boxes for distribution among the patriots. Next day, April 24, a crowd of some eight thousand people—roughly a third of New York’s population—assembled in front of City Hall to hear from the Committee of Sixty. Crossing the line between resistance and revolution, the Sixty proposed that all New York patriots subscribe to a General Association, that a Provincial Congress assume control of the colony, that government of the city be turned over to a new Committee of One Hundred, and that immediate steps be taken to defend the city from a British attack—a distinct possibility, given that Gage’s position in Boston was clearly untenable. “People here are perfectly fearless,” Robert R. Livingston told his wife, Mary.

Nominations and elections for the Committee of One Hundred took place within a few days. Though dominated by moderates, its members included such radicals as Daniel Dunscomb, chairman of the Mechanics Committee, whose presence helped push the committee to widen its authority. At a mass meeting of city residents on April 29, the One Hundred promulgated Articles of Association drafted by James Duane and John Jay. Those who signed pledged “never to become Slaves” and to obey the measures of the Continental Congress, the Provincial Congress, and their local committees.

Three hundred and sixty armed men, led by Isaac Sears, meanwhile seized the keys of customs collector Andrew Elliot. Sears declared the port of New York closed until further notice. For another week or two, Sears’s house on Queen Street seemed to be the effective seat of government and headquarters for the company of militia that nightly patrolled the city. William Smith Jr. could hardly believe what was happening. “It is impossible,” he wrote on April 29, “fully to describe the agitated State of the Town since last Sunday, when the News first arrived of the Skirmish between Concord and Boston. At all corners People inquisitive for News. Tales of all kinds invented believed, denied, discredited. .. . The Taverns filled with Publicans at Night. Little Business done in the Day.. . . The Merchants are amazed and yet so humbled as only to sigh or complain in whispers. They now dread Sears’s Train of armed Men.”

This was revolution—“total revolution,” in the words of one Tory. Even if Great Britain and the colonies did manage to compose their differences—the Continental Congress continued to insist that the colonies weren’t seeking independence—the legitimacy of colonial political institutions had boiled away. Governmental power was passing to a network of committees that responded to, and included representatives of, what another Tory called “the lower class of people.” The city is now ruled, said yet another, “by Isaac Sears & a parcel of the meanest people, Children & Negroes.”

Isaac Low, Abraham Walton, and a handful of other prominent Tories, still clinging to the hope of a peaceful solution, remained in New York to take part in the Provincial Congress. Most took flight. James De Lancey, merchant John Watts, and Colonel Roger Morris scrambled to get on the May 4 packet to England. Printer James Rivington fled to the protection of a British warship in the harbor. Governor Golden retreated to his Flushing estate, writing to Lord Dartmouth that “Congresses and committees are now established in this Province and are acting with all the confidence and authority of a legal Government.”

President Myles Cooper of King’s College left town as well, chased from his bed one night in May by “a murderous band.” A student named Alexander Hamilton is said to have helped Cooper escape by delaying his pursuers with a lengthy “harangue” on Cooper’s front porch. Hamilton, who had come up to New York from the West Indian island of Nevis only two years earlier, was already the author of two highly regarded pamphlets supporting the Continental Congress; like other conservative patriots, however, he detested mobs.

The New York Provincial Congress took over the vacant Assembly chamber in City Hall on May 23 and moved quickly to consolidate its authority. It called for the creation, where they didn’t already exist, of “county committees, and also sub-committees . . . to carry into execution the resolutions of the Continental and this Provincial Congress.” It instructed Queens and Richmond counties to send delegates at once. It warned everyone who hadn’t yet subscribed to the General Association to do so by July 15 or suffer the consequences. It also stepped up the pace of military preparations by creating a Military Association—in effect, a revolutionary militia—and launching a campaign to recruit five regiments. Alexander McDougall, the Wilkes of America, personally took charge of raising a regiment from the city; the First New York, as it would be known, consisted largely of workingmen.

Association militia were soon drilling in the Fields and patrolling the streets while gangs of laborers erected barricades, dug trenches, and threw up breastworks. The Committee of One Hundred, assuming the duties of municipal government, meanwhile began to grapple with such familiar problems as regulating wages and prices and providing relief for the poor.

The speed with which both the One Hundred and the Provincial Congress got to work reflected not only the quickening pace of events but also the continued concern among more cautious patriots that popular enthusiasm not be allowed to get out of control. “Good and well-ordered governments in all the colonies,” explained John Jay, would “exclude that anarchy which already too much prevails.” James Duane, who admitted that “licentiousness is the natural effect of a civil discord,” felt “it can only be guarded against by placing the command of the troops in the hands of men of property and rank.” Easier said than done, Gouverneur Morris reflected, inasmuch as “the soldiers from this Town [are] not the Cream of the Earth but the Scum” and are “officered by the vulgar.” Even Alexander McDougall felt apprehensive. “I fear liberty is in danger from the licentiousness of the people,” he confessed.

For many moderates, these fears were underscored on June 6, when the last of the Fort George garrison, a hundred or so soldiers from the Royal Irish Regiment, were withdrawn from the city to the sixty-four-gun warship Asia (in part, according to one source, because too many of them had deserted to the patriots). Led by Marinus Willett, some Liberty Boys intercepted the column as it marched down Broad Street, commandeering its muskets, ammunition, and baggage. Escorts provided by the Provincial Congress and Committee of One Hundred endeavored to stop the outrage, without success. Shortly thereafter, a party of Liberty Boys raided a royal storehouse at Turtle Bay, likewise over the objections of representatives from the Provincial Congress. Knowing that a failure to respond might well explode its authority, the Congress ordered Willett to return everything he and his men had made off with. Independent “attempts to raise tumults, riots, or mobs” couldn’t be tolerated, it said sternly.

Willett backed down, but no one expected that to end the matter. When a crowd burned a supply barge from the Asia in July, the embarrassed Congress built a replacement; when that too was destroyed, Congress again condemned unauthorized attacks on persons and property and ordered the construction of another replacement, this time dispatching militia to guard it.

The rapidly escalating crisis between Britain and the colonies made it all the more difficult for the Provincial Congress to stay on top of the situation in New York. On June 25, 1775, General George Washington passed through town on his way to take command of the troops besieging Gage in Boston. Cheering crowds lined the streets and church bells pealed as a battalion of militia and members of the Provincial Congress escorted him down Broadway to Hull’s Tavern, where he would spend the night.

Later that same day, Governor Tryon returned to resume his duties after a fourteen-month absence. A smaller and much more restrained crowd greeted the governor at the foot of Broad Street and walked with him over to Hugh Wallace’s town house on Bowling Green, where he had lodgings for the night. It was the first of many hard lessons, he said, in the “impotence of His Matys Officers and Ministers of Justice in this Province,” and it now seemed “very probable I may be taken Prisoner, as a state Hostage, or obliged to retire on board one of His Majestys Ships of War to avoid the insolence of an inflamed Mob.”

It came to that more quickly than the governor might have imagined. Only a week before he and Washington reached New York, a second clash between colonial forces and Gage’s redcoats took place at Bunker Hill. Then, over the summer of 1775, Congress rejected a conciliatory plan proposed by Lord North. It offered instead the so-called Olive Branch Petition, pleading with the king to cease hostilities. It also drew up a “Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms,” explaining that the colonists had acted only in self-defense and were “with one mind resolved to die freemen, rather than to live slaves.” In August Congress launched an invasion of Canada to prevent its use as a base of operations against the colonies. “The Americans from Politicians are now becoming Soldiers,” Tryon reported to the home government.

On the night of August 23 John Lamb’s artillery company undertook to remove two dozen cannon from the Grand Battery at the southern tip of Manhattan. While they were at it, they exchanged fire with a boatload of soldiers from the Asia, lying in the East River just off the foot of Wall Street. In retaliation, the commander of the Asia ordered a full thirty-two-gun broadside of solid shot into the sleeping town. Apart from a hole in the roof of Fraunces Tavern, no great damage was done. But for the thousands of halfdressed, panic-stricken residents who tumbled out of their beds into the streets, it was an effective reminder of the city’s vulnerability to naval bombardment. Many made plans to leave.

Isaac Sears soon left town too, albeit for reasons of another kind. In October 1775 the Continental Congress recommended the arrest of all royal officials remaining in the colonies; not only did the New York Provincial Congress seem reluctant to take so decisive a step, but when soldiers pilfered a royal store, the Congress ordered everything returned rather than risk another bombardment from the Asia. Incensed by this timidity, Sears sold his house, moved to Connecticut, and proceeded to organize an armed troop made of sterner stuff. “There are many Enemies to the cause of Freedom” in New York, he declared. Governor Tryon, suspecting that Sears had set his sights on him in particular, slipped off to William Axtell’s Flatbush estate; from there he made his way to a merchant ship, the Duchess of Gordon, anchored safely under the guns of the fleet in the harbor.

The winter of 1775-76 brought a steady stream of news confirming that Tryon would never again set foot in the city without a fight. Parliament rejected the Olive Branch Petition. The king formally proclaimed the colonies to be in a state of rebellion and closed them to all trade. General Gage had been replaced by General Sir William Howe, and a punitive expedition force under General Henry Clinton, General Charles Cornwallis, and Admiral Peter Parker was expected to descend on North Carolina sometime in January.

Throughout the colonies, the reaction to these developments was an eruption of popular resentment against the monarchy that killed the chances of a reconciliation with the mother country. Americans now began to talk openly of independence; the case for it was clinched in January 1776 by Tom Paine’s Common Sense, which denounced “the Royal Brute of Great-Britain” and catalogued all the reasons why the colonies would be better off on their own.

Tryon’s departure left New York’s Tories both demoralized and defenseless. During the late summer of 1775 the pressure on them became intolerable. A series of resolves by the Provincial Congress provided that anyone aiding the enemies of America, or even denying the authority of congresses and committees, could be disarmed, fined, imprisoned, and banished. To Isaac Sears, this was the long-overdue summons to action. He galloped down from Connecticut with one hundred men and smashed up James Rivington’s printshop. After announcing that they acted independently of all congresses and committees, Sears and his band galloped away again singing “Yankee Doodle.” (Who, it will be recalled, stuck a feather in his cap and called it “macaroni”—a deft little dig at the flamboyant style of the same name associated with the upper classes on both sides of the Atlantic.)

Printer Samuel Loudon came in for similar treatment the following March when he printed The Deceiver Unmasked, an attack on Paine from the pen of the Rev. Charles Inglis. Led by Sears, Lamb, and McDougall, a band of Liberty Boys raided Loudon’s shop, destroyed his press, and burned every one of Inglis’s pamphlets.

Lukewarm patriots as well as Tories fled New York in droves. By the end of 1775 more than ten thousand of the city’s twenty-five thousand inhabitants had gone; thousands more would go in the months that followed. By July 1776 only five thousand or so remained. “To see the vast number of houses shut up, one would think the city almost evacuated,” wrote one departing Tory. “Women and children are scarcely to be seen in the streets. Troops are daily coming in; they break open and quarter themselves in the houses they find shut up. Necessity knows no law.”

Outside the city, however, the Tory problem proved harder to resolve. Opposition to the Association ran so high in Kings County that in August 1775 the Provincial Congress dispatched a committee to rally the fainthearted and disarm enemies to the cause. General Nathaniel Woodhull was likewise ordered to secure Queens County, but the task there was so difficult that the Provincial Congress finally appealed to the Continental Congress for help. Congress answered by sending Colonel Nathaniel Heard of New Jersey. Heard marched through Queens in January 1776 with twelve hundred militia and a list of “inimicals” who had refused to sign the Association. Nearly a thousand Tories or suspected Tories were rounded up and disarmed; nineteen were taken away to Philadelphia for questioning. Heard made a similar sweep of Staten Island a month later.

No sooner had Colonel Heard departed than General Charles Lee arrived in New York with two regiments of New England militia. A strange and moody man who surrounded himself with dogs, Lee was already something of a sensation among the patriots. His soldiers adored him, Washington depended on him, and the Continental Congress seemed to think he could do no wrong. For one thing, Lee was a retired British officer with more impressive military experience than anyone else on the American side, experience that had proved vital during the siege of Boston in the summer and fall of 1775. He was also an out-and-out radical who detested monarchy, spoke admiringly of democracy, and advocated immediate independence for the colonies.

To Lee’s way of thinking, the struggle against Great Britain was an authentic popular uprising, which required the kind of grass-roots mobilization that French revolutionaries would later call a levée en masse. If the war continued, he argued, it could be won only by citizen-soldiers who made up the rules as they went along, not by professional troops employing the aristocratic “Hyde Park” tactics of conventional European armies. True to his principles, he made his headquarters at Montayne’s tavern on Broadway, just across from the Fields and once the principal meeting place for radical patriots. It isn’t hard to see why the New England troops and the city’s mechanics loved him—or why he made the Provincial Congress extremely nervous. Paine thought him a marvel well before they met.

Congress wanted Lee in New York partly to keep up the pressure on local Tories (Lee relished that kind of assignment) but mostly because a British attack on the city was becoming more likely every day. The American invasion of Canada had just ended in disaster: General Montgomery was dead, and the First New York had suffered heavy casualties (one of McDougall’s sons had been killed, the other taken prisoner). General Howe was meanwhile preparing to leave Boston, most likely for New York.

Until General Gage had left to occupy Boston in 1768, after all, New York had served as the headquarters for British forces in North America. It was familiar territory, socially and politically as well as militarily. Its central location and unsurpassed harbor and port facilities made it the logical staging area for further operations against the rebels, while control of the Hudson-Lake Champlain axis would isolate rebellious New England from the rest of the colonies. The many Tories in and around the city would surely give His Majesty’s forces a warmer welcome than they had received in Boston; their presence would, of course, eliminate an important center of political and social radicalism and boost the morale of Tories throughout the colonies. Taking New York would be an easy matter, in any case: as Peter Stuyvesant had learned a century before, New York couldn’t be defended without a navy, and Congress had no navy to speak of. “I feel for you and my other New York friends,” said an Englishman sympathetic to the American cause, “for I expect your city will be laid in ashes.”

Lee knew full well that New York couldn’t be held against an all-out assault by an enemy army and fleet; he also knew that handing it over without a fight would give the enemy a dangerous military and psychological advantage. The only course, he reasoned, was to put up a stout resistance and extract as high a price for the city as possible.

As the spring of 1776 approached, Lee threw himself into the business of preparing New York for invasion. To prevent hostile warships from entering the East River, he ordered construction of thirteen forts and batteries on Manhattan and Long Island. To forestall an attack by land, he barricaded the city’s major streets and placed an additional half-dozen forts and batteries at strategic points between the city and King’s Bridge at the northern end of Manhattan; one, near what is now the intersection of Grand and Center streets, was nicknamed “Bunker Hill.” To keep an enemy from taking Brooklyn Heights, the high ground that commanded the city from across the East River, Lee strung a chain of forts, redoubts, breastworks, and trenches between Gowanus Creek and Wallabout Bay (built, for the most part, by levies of Kings County slaves.) He sent Isaac Sears with an armed party over to Long Island to keep the Tories there in line. He also issued manifestos to inspire the citizenry and hosted a dinner party for Tom Paine, who came up from Philadelphia.

After little more than a month of this feverish activity, Lee moved on to organize the defenses of Charleston, leaving General William Alexander in command of the city. He’d done his work well: New York wasn’t safe, but it was getting ready.

In mid-March, as expected, Howe finally pulled out of Boston and headed for Halifax, there to prepare for the move against New York. At once Washington began shifting Continental troops down to the city, then came down himself in mid-April to oversee military preparations. Every able-bodied man in the city, including servants and slaves, was pressed into work on fortifications.

New batteries were built on Red Hook, Governors Island, Paulus Hook, and elsewhere, bringing the total to fourteen, with 120-odd cannon. To prevent enemy ships from entering the Hudson, construction began on a pair of forts that straddled the river between upper Manhattan and New Jersey—one dubbed Fort Washington, the other Fort Lee.

By the beginning of the summer of 1776, the arrival of better than ten thousand troops had transformed the city into an armed camp, and (Washington hoped) more were on the way. Military authorities established two huge bivouacs, one just north of town near present-day Canal Street, the other across the East River on the slopes above the Brooklyn ferry landing, and many other pieces of open ground were crammed with tents, huts, shacks, wagons, and piles of supplies. To build barricades and meet the demand for firewood, work parties ripped up fences and cut down the many trees for which the city had been famous. Warehouses and loft buildings, especially those belonging to departed Tories, were commandeered for military purposes, as were the new city hospital and the classrooms of King’s College.

Town houses and country retreats belonging to the Apthorp, Bayard, Watts, Stuyvesant, Walton, and Morris families—every one a talisman of the old order in the city—were turned over to soldiers who draped their feet on the furniture, tore up the parquet floors for fuel, threw garbage out the windows, and corralled their horses in the gardens. Washington himself settled the army’s general headquarters on Richmond Hill, the country estate of Abraham Mortier. Protests were pointless; indeed protesting seemed only to make matters worse. Oliver De Lancey, brother of the late governor and uncle of Captain James De Lancey, ordered army woodcutters off his estate on the west side of Manhattan at 23rd Street. Once they might have retreated before the wrath of so great a personage; now, fired with a new egalitarian zeal, they brushed him aside and set upon his prized orchards with a vengeance. By June, De Lancey too had fled to the Duchess of Gordon.

Everybody complained about price-gouging by shopkeepers, tradesmen, and ferryboat operators. Nobody knew what to do about waste disposal and sanitation, which—along with the inadequate supply of potable water, always a problem—constituted an open invitation to epidemic disease. The provost marshal imposed a curfew on the troops and struggled to control the sale of alcohol, but drunkenness and rowdyism were a source of constant concern. So was the “Holy Ground” district west of Broadway, where (as one American officer wrote his wife) “bitchfoxy jades, jills, hags, strums, [and] prostitutes” flourished as never before. At Washington’s request, the authorities removed the four hundred indigent residents of the almshouse and ordered that the “women, children, and infirm persons in the City of New York be immediately removed from the said City” to nearby rural counties.

Despite the best efforts of military and civilian officials, the city and its environs were still crawling with Tory spies and sympathizers, many in positions of considerable importance. Throughout the spring and early summer, rumors flew that Tories in New York and New Jersey were recruiting soldiers, stockpiling weapons, and sabotaging military equipment and installations on the assumption that the redcoats would show up any day. Tensions ran especially high on Long Island, where patriot troops didn’t get along with rural villagers and Tory “skulkers” hid out in the Rockaway marshes.

The New York Provincial Congress hadn’t been much help. Since the previous summer—specifically, some said, after the Asia cannonaded the city in August—that body seemed to have come down with a bad case of the jitters. It agonized about prohibiting local merchants and farmers from selling supplies to British warships still in the harbor. It agonized about raising money. It agonized about spending money. It agonized about the havoc wrought by ten or twenty thousand young men under arms (especially Lee’s New Englanders, some of whom were allegedly talking about burning the city if all else failed). After agonizing, too, about the Tories, it created a special Committee for the Detection of Conspiracies to chase them down, but without much success. Washington thought the Provincial Congress was a pack of dithering nincompoops and quarreled with it about almost everything. Patriots elsewhere spoke of New York as the weakest link in the chain.

In New York City, as opposed to the colony as a whole, the revolutionary movement actually gained momentum after mid-1775. The final disintegration of royal authority, the flight of thousands of Tories, the impending attack by His Majesty’s forces, and the presence of a revolutionary army had completed the shift to radical rule. There, in the words of Hugh Hughes, “the people are constantly treading on their leaders’ heels, and, in a hundred cases, have taken the lead of them.” Suspected Tories were forced to recant in public, then tarred and feathered, ridden through town on rails, or forced to parade the streets holding candles.

The well-organized and militant Mechanics Committee (soon referring to itself as the Mechanics Union) had now become the dominant voice in municipal affairs. It carefully watched—and criticized, when necessary—every move of the Committee of One Hundred. When a local printer advertised a pamphlet attacking Common Sense, the mechanics urged him not to sell it; when he refused, they confiscated and burned all the copies. When it seemed the Conspiracy Committee wasn’t moving fast enough, the mechanics ran suspected Tories out of town. When elections were held for a new Provincial Congress in April, the mechanics refused to endorse McDougall because he had stayed in town when his regiment marched off to Canada; McDougall lost. All spring, while the Provincial Congress hemmed and hawed about a final break from Great Britain, the mechanics stressed the essential connection between revolution and independence: revolution needn’t have led to independence, nor independence to revolution, but neither could get very far without the other.

At the end of May, prodded by the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, the Provincial Congress recommended new elections so that New Yorkers could vote on the issue of forming a new state government. The result was an exhilarating, free-wheeling debate over fundamental political principles, in which the city’s mechanics advocated ideas that not too many years earlier would have landed them in jail: republicanism, constitutionalism, unicameral legislatures, limited executive power, annual elections, the secret ballot, universal manhood suffrage, rotation of office, equal apportionment, the popular election of all local officials, religious toleration, and even the abolition of slavery. The Mechanics Union also declared that no frame of government should be adopted for the state without having first been ratified by the people.

When the new Provincial Congress assembled in mid-June, a number of the most conservative delegates had been unseated by men whose views were decidedly more radical—among them Daniel Dunscomb, a former chairman of the Mechanics Committee—and there now appeared to be a slim majority in favor of national independence.

Under the leadership of John Jay, moreover, the Conspiracy Committee finally began to show some initiative in dealing with the Tory problem. Its biggest discovery was that one of Washington’s own bodyguards, a certain Thomas Hickey, had conspired with several others, probably including Mayor David Mathews, to kidnap or assassinate the American general. Hickey was court-martialed and hanged near the Fields in the presence of a huge throng of soldiers and civilians. Matthews was seized at his Flatbush residence and taken to prison in Connecticut.

On June 29, the day after Mickey’s execution, lookouts saw the long-awaited fleet from Halifax streaming past Sandy Hook toward the Narrows between Staten Island and Long Island—better than a hundred vessels in all, bearing thousands of regular troops. To one amazed American rifleman, the harbor resembled “a wood of pine trees.” “I could not believe my eyes,” he recalled. “I declare that I thought all London was afloat.” Within a day or so nine thousand redcoats had been landed on Staten Island and set to work building fortifications.

Washington meanwhile exhorted his soldiers to be ready to fight to the last, convinced that the city was defensible. He wasn’t alone. Colonel Henry Knox, a self-taught artilleryman from Massachusetts, assured Washington that the cannon emplacements now ringing the city would deter a British attack. The Provincial Congress, more cautious, thought it best to move up to White Plains.

The British fleet anchored off Staten Island, 1776. Sketch by Archibald Robertson. (Spenser Collection. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

On July 2, 1776, Congress voted in favor of independence; two days later it adopted Jefferson’s Declaration. New York’s Provincial Congress gave its assent on July 9. At six P.M. that same day, the Declaration was read to Washington’s troops mustered in the Common. A rowdy crowd of soldiers and civilians (“no decent people” were present, one witness said later) then marched down Broadway to Bowling Green, where they toppled the statue of George III erected in 1770. The head was put on a spike at the Blue Bell Tavern near Fort Washington at present-day Broadway and 181st Street; the rest of the statue, some four thousand pounds of lead, was hauled off to Connecticut. There it will “be run up into musket balls for the use of the Yankees,” declared one soldier, “It is hoped that the emanations from the leaden George will make . . . deep impressions in the bodies of some of his red-coated and Tory subjects.”

Within a week the King’s Arms on City Hall had likewise come down, along with other trappings of monarchy adorning Trinity and St. Paul’s. “Every Vistage of Royalty, as far as been in the power of the Rebels, [is] done away,” said Tryon glumly. Reported another observer: “The Episcopal Churches in New York are all shut up, the prayer books burned, and the Ministers scattered abroad. . . . It is now the Puritan’s high holiday season and they enjoy it with rapture.”

His Majesty’s army was ready for a fight too, convinced it would make short work of the rebels defending New York. Despite the recent unpleasantness in Boston, its officers still believed that Washington’s so-called army was a mere republican rabble, without the training or leadership necessary to hold off seasoned veterans. This unshakable class contempt was reinforced by the knowledge that large numbers of recent immigrants had thrown in with the patriots. “The chief strength of the Rebel Army at present consists of Natives of Europe, particularly Irishmen,” observed Captain Frederick Mackenzie of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers.

Symbolic regicide in New York, a nineteenth-century interpretation, painted by John C. McRae, of New York patriots pulling down the statue of George III. Legend has it that the head was later rescued by a British officer and shipped back to England. (© Museum of the City of New York)

General Howe, though, didn’t want an all-out fight for New York. It wasn’t a question of winning but of how much it would cost to win. He couldn’t forget the carnage at Bunker Hill, where a frontal assault against entrenched American positions had cost him 40 percent of the men under his command in a single afternoon, and it was clear that Washington expected him to try the same thing again. Howe knew, too, that if Washington fought well the city could easily be left unfit as a base for further military operations.

As always, there were also political considerations. Sympathy for the American cause had widened steadily among the British middle and laboring classes, who linked it to demands for domestic political reform. London voters chose two Americans as sheriffs in 1773. John Wilkes, installed as mayor of London in 1775, was pressuring the crown to remove ministers hostile to American rights. A new generation of radical Whig pamphleteers—Catharine Macaulay, Major John Cartwright, Granville Sharp, James Burgh, Richard Price, Joseph Priestly—were all the while bombarding the reading public with warnings that liberty was in mortal peril on both sides of the Atlantic. New York readers paid careful attention. Local papers reprinted long extracts from parliamentary debates, British journals, and private correspondence. Local bookstores stocked a full range of controversial books and pamphlets, including Price’s famous Observations on the Nature of Civil Liberty, and the Justice and Policy of the War with America (1776).

Aware that further conflict with America would require expenditures of blood and money that the government could ill afford—resistance to domestic recruiting had already obliged it to hire soldiers from the Landgrave of Hesse in Germany—even moderate Whigs like Edmund Burke were urging Lord North to go easy. General Howe’s brother, Admiral Lord Richard “Black Dick” Howe, was in fact already on his way to the colonies at the head of a commission authorized by the king, reluctantly, to negotiate with Congress.

Both the Howe brothers felt personally well disposed toward the colonies. Both remembered with gratitude that the Massachusetts legislature had erected a monument in Westminster Abbey to the memory of an older brother killed at Ticonderoga during the Seven Years War. Both believed, vaguely, that the Americans had some cause for complaint. Both continued to believe in the possibility of a peaceful reconciliation. Both sensed that the annihilation of Washington’s army in New York would make reconciliation impossible and doom Britain to resolve the American crisis by force of arms alone—an unhappy prospect even for men who made a profession of war.

The course that both preferred, all things considered, was to make the colonies realize the danger they faced without closing the door to negotiations. Confronted with the combined might of His Majesty’s army and navy, Washington and the Congress (so the theory went) would come to their senses and return to the fold. A case could be made, in fact, that General Howe’s arrival off Staten Island was already having the desired effect. Virtually the entire Staten Island militia had joined the British army, and every day, from New Jersey, from Long Island, and even from Manhattan, scores of Tories were slipping through rebel lines to join the fleet. At a moment’s notice, they said, thousands more were ready to rise against the tyranny of Congress; Washington’s army, they said, was disintegrating.

Howe’s first move, accordingly, was a modest but revealing probe of the American defenses. On July 12 a pair of British warships, the gunship Phoenix (forty-four guns) and the frigate Rose (twenty-eight guns), detached themselves from the fleet anchored off Staten Island and crossed the upper bay toward the mouth of the Hudson. American cannon blazed away from Red Hook, Governors Island, Paulus Hook (New Jersey), and Manhattan, but to no effect. While the captain of the Rose and his officers sipped claret on the quarterdeck, the two sailed serenely into the Hudson, past the city, and all the way up river to Tarrytown, some thirty miles to the north.

Washington was appalled. His artillery did more harm to themselves than to the enemy—the only casualties of the day occurred when an ill-trained gun crew on the Battery blew themselves up—while many of his men and officers abandoned their positions to gawk at the spectacle. “Such unsoldierly conduct,” he explained to the Provincial Congress, would “give the enemy a mean opinion of the army.”

Just as unfortunate, casual return fire from the British warships, though doing no great damage, caused pandemonium among the civilian population. A few of Washington’s staff were convinced by what had happened that this was the wrong place and the wrong time for a head-on battle with the British. Washington, however, remained obstinate in his determination to fight for the city. Admiral Lord Howe and his fellow commissioners, who had by coincidence arrived on the evening of the twelfth (along with 150 ships and fifteen thousand more troops), got nowhere with the American commander in the days that followed. He firmly refused to see them; negotiation was a matter for Congress, he explained, besides which Howe had made the mistake of writing to “Mr. George Washington” rather than “General George Washington.”

Two weeks passed. Generals Henry Clinton and Lord Charles Cornwallis, having failed to capture Charleston, came up through the Narrows on August 1 with eight regiments of veterans and several men-of-war. (For Clinton this was a homecoming of sorts: the son of Admiral George Clinton, royal governor of New York from 1743 to 1753, he had spent much of his boyhood in the city.) Several days behind Clinton and Cornwallis came a convoy of twenty-two ships with additional regiments from England and Scotland. On August 12 a fleet of over a hundred vessels crossed the bar at Sandy Hook, bringing in nearly nine thousand Hessian mercenaries under General Philip von Heister. To Ambrose Serle, Lord Howe’s secretary, it was a scene never to be forgotten. “So large a fleet made a fine appearance upon entering the harbor, with the sails crowded, colors flying, guns saluting and the soldiers . . . continually shouting.” In New York, “the tops of the houses were covered with gazers,” the wharves were “lined with spectators,” and apprehension mounted as “ship after ship came floating up” to drop anchor off Staten Island in the distance. Hundreds more residents gathered their belongings and fled. Within days, as Pastor Schaukirk of the Moravian Church described the scene, the city looked “in some streets as if the Plague had been in it, so many houses being shut up.”

General Howe now had at his disposal two men-of-war and two dozen frigates mounting a combined twelve hundred cannon, plus four hundred transports, some thirty-two thousand disciplined and well-equipped troops in twenty-seven regiments, and thirteen thousand seamen. It was the largest force ever assembled in the colonies and the largest British expeditionary force in history thus far, marshaling better than 40 percent of all men and ships on active duty in the Royal Navy. Already the cost exceeded £850,000—a breathtaking sum for the time. Washington, by contrast, had no ships to speak of and probably fewer than twenty-three thousand men under his command, mostly raw militia without adequate equipment, training, or experience. About half of them weren’t fit for duty thanks to an epidemic of camp fever (dysentery) that had broken out in the overcrowded town across the bay.

But still Washington didn’t waver, not even when the fever laid up Nathanael Greene, his best general and the commander of the all-important Brooklyn Heights defenses. Instead, to replace Greene, Washington turned to John Sullivan of New Hampshire. Sullivan not only lacked Greene’s ability, he knew nothing about the terrain on which he was supposed to fight.

By this time six weeks had passed since General Howe’s arrival on Staten Island, and it was clear that he was going to have to do something fairly soon. On August 17 Washington ordered warnings posted throughout the city that an attack was near and urged all civilians to get out immediately. Next day the Phoenix and the Rose dropped back down the Hudson from Tarrytown. Again the American batteries thundered away at them, again with no effect.

On August 22 the British finally made their move. Under the cover of six warships, scores of flatboats, longboats, and bateaux ferried fifteen thousand redcoats across the Narrows to what is now Dyker Park on the Gravesend shore of Long Island. Set against “the Green Hills and Meadows after the Rain and the calm surface of the water,” Ambrose Serle observed, the landing made “one of the most picturesque Scenes that the Imagination can fancy or the Eye behold.” Similarly impressed, a light guard of two hundred Pennsylvania riflemen stationed near the beachhead withdrew without offering any opposition. More redcoats and five thousand Hessians followed on the twenty-third and twenty-fourth, bringing the total enemy force to around twenty-one thousand.

As the British settled in, their positions stretched in a four-mile arc from the village of New Utrecht on the west (site of Howe’s temporary headquarters) through Gravesend to Flatbush (where the Hessians were billeted) and Flatlands (the main British camp, at the intersection of what is now Flatbush Avenue and Kings Highway). Governor Tryon appeared on the scene and called out the local militia, some six hundred men in all, to aid the regulars. Joined by two Tory regiments raised among refugees from New York, they imparted to this invasion the tensions of civil war. Eight hundred slaves had fled to the British as well and were being organized into a labor regiment.

Howe and his officers professed to be delighted by their reception on Long Island. “The Inhabitants receiv’d our people with the Utmost Joy, having been long oppress’d for their Attachment to Government,” said one. “They sell their things to the Soldiers at the most Reasonable Terms & they kept up their stock in spite of the Rebels.” In Flatbush and other Kings County hamlets, however, fear and confusion reigned. Many years later, the elderly mother of Gertrude Lefferts Vanderbilt still remembered when a “rumor reached us that the soldiers were rapidly approaching. The whole village was in commotion. . . . Women and children were running hither and thither. Men on horseback were riding about in all directions.”

On the twenty-third Washington sent reinforcements to Sullivan and went over from New York to study the situation personally. On the twenty-fourth he dispatched more reinforcements under General Alexander, bringing the American total to around seven thousand. He also ordered General Israel Putnam of Connecticut to go over and see what he could do. “Old Put” was a capable veteran of the French and Indian War who had faced Howe at Bunker Hill. “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes,” he is supposed to have said. “Then, fire low.”

Putnam took charge of the Brooklyn Heights defenses, leaving Sullivan with around twenty-eight hundred men to cover the outer line along the Heights of Guan, the rocky, heavily wooded ridge of the glacial moraine that ran down the middle of Long Island. Only four roads traversed this barrier—at Gowanus, Flatbush, Bedford, and Jamaica—and even a relatively small force should have been able to defend it against an army advancing north toward Brooklyn Heights.1

Someone, however, had neglected to place troops at the Jamaica Pass, on the far left of the American line. A civilian spy (probably one of many Kings County Tories who attached themselves to the British army) soon brought word to General Clinton of the gap, and Clinton persuaded Howe to attack it in strength. Just after sundown on the twenty-sixth, a Monday, Howe, Clinton, and Cornwallis led better than ten thousand regulars in a two-mile-long column out of Flatlands toward New Lots in the east; with them went two companies of Long Island Tories under Oliver De Lancey. To deceive any watching Americans, they moved quietly and left their campfires burning. At New Lots they turned north to Jamaica; at about three A.M. on the twenty-seventh, they marched through the Jamaica Pass without opposition. They then turned west along the Jamaica Road toward the village of Bedford—today the intersection of Nostrand Avenue and Fulton Street in Bedford-Stuyvesant—where they arrived around 8:30 A.M. and fired two signal guns to alert the rest of the army.

Two smaller enemy forces now swung into action. At the Flatbush Pass in the center of the American line, five thousand Hessians attacked eight hundred Americans under General Sullivan. Realizing from the signal gun that Howe had somehow worked his way around him, Sullivan tried to fall back but couldn’t. Trapped between Howe’s light infantry coming down from Bedford and bayonet-wielding Hessians pouring up from Flatbush, his men broke and were slaughtered. “The greater part of the riflemen,” reported one German officer, “were pierced with the bayonet to trees.” A jubilant British officer gloated: “It was a fine sight to see with what alacrity they dispatched the Rebels with their bayonets after we had surrounded them so they could not resist.” Hundreds of Americans threw down their weapons and raced to reach safety behind the lines in Brooklyn Heights. Sullivan himself was captured in a cornfield near what is now Battle Pass in Prospect Park. It was over before noon. Although most of the American dead were buried on the grounds of the Flatbush Reformed Dutch Church, area farmers were still turning up bones in their fields well into the next century.

At Gowanus, on the far right of the American line, General James Grant had meanwhile thrown seven thousand redcoats and two thousand Royal Marines, supported by two companies of Long Island Tories, against two thousand troops from Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Delaware commanded by General Alexander. Alexander’s men fought gamely to keep control of the high ground—now called Battle Hill in Green Wood Cemetery—until the collapse of the American center at Flatbush made their position hopeless. Redcoats from Bedford were closing in behind them, while Hessians were crashing through the woods on their left. To give the rest of his force time to escape across the tidal flats along Gowanus Creek, Alexander counterattacked with barely four hundred Maryland troops.

Washington, who watched Alexander advance from a vantage point where Court Street now crosses Atlantic Avenue, reportedly wrung his hands and cried out: “Good God! What brave fellows I must this day lose!” Survivors remembered the “confusion and horror” as the fleeing Americans tried desperately to cross eighty yards of muddy flats under a hail of British canister, grape, and chain. “Some of them were mired and crying to their fellows for God’s sake to help them out; but every man was intent on his own safety and no assistance was rendered.” After savage fighting on the Gowanus Road near the Cortelyou House (now known as the Old Stone House, at Fifth Avenue and 3rd Street), Alexander was captured. By two P.M. all but nine of the Marylanders had been killed or taken prisoner. Thanks to their valor, however, hundreds of other Americans managed to wade or swim to solid ground on the other side of the creek, and hence to safety in Brooklyn Heights.

Had Howe kept up the chase, it is likely that the demoralized remnants of Washington’s army would have been driven into the East River. In only a few hours of fighting roughly twelve hundred Americans had died, and another fifteen hundred were wounded, captured, or missing—among them three generals and ninety-odd junior officers. The British, by contrast, reported only sixty dead and three hundred wounded or missing.

The American retreat across Gowanus Greek, by Alonzo Ghappel. (© Collection of The New-York Historical Society)

Despite pleas by Clinton, Cornwallis, and others to finish what they had begun, Howe halted and began preparations for a formal siege—either because he didn’t have the heart for another Bunker Hill-like frontal assault or because he hoped that the rebels would give up without a struggle. Tuesday evening and all day Wednesday his forces dug trenches and probed the American defenses in a cold, soaking rain that made it impossible for men on either side to build campfires or keep their powder dry. Although the storm ended by noon on Thursday the twenty-ninth, two days after the battle, Howe continued to bide his time—and gave Washington the opening for one of the boldest strokes of the war.

That evening, as night fell, Washington ordered all units to form up and move down from the Heights to the ferry landing on the East River shore. “We were strictly enjoined not to speak, or even cough,” one private recalled. “All orders were given from officer to officer, and communicated to the men in whispers.” At water’s edge, a regiment of fishermen from Salem and Marblehead with commandeered rowboats, barges, sloops, skiffs, and canoes waited to ferry the army across to New York. Working silently, hour after hour, they rowed back and forth, under the cover of a thick fog that concealed the maneuver from enemy sentries. The last of ninety-five hundred men—Washington’s entire force—reached Manhattan just as dawn broke on Friday. Not until 8:30 would a chagrined Howe learn that the Americans had slipped his grasp.

Even though everyone knew that Washington’s audacity had saved the Revolution, there was no celebrating in New York. Pastor Schaukirk, roused out of bed to watch the soldiers straggle into town, saw only shock and exhaustion on their faces. “The merry tones on drums and fifes had ceased,” he reported. “It seemed a general damp had spread, and the sight of the scattered people up and down the streets was indeed moving. Many looked sickly, emaciated, cast down, etc.; the wet clothes, tents—as many as they had brought away—and other things were lying about before the houses and in the streets to dry.”

Washington’s escape from Brooklyn Heights, by J. C. Armytage. (© Collection of The New-York Historical Society)

On September 11 Lord Howe met with a congressional delegation consisting of Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Edmund Rutledge at the stone manor house Captain Christopher Billopp had built around 1680 in Tottenville, Staten Island. If Congress would revoke the Declaration of Independence, Howe repeated, the British would pardon all who had taken up arms against the king (essentially the same offer they had made to Washington a month before). Independence isn’t negotiable, replied the American delegates—with which the so-called conference came to an end.

Now even Washington could see that his days in New York were numbered. His dispirited army was falling apart—in one week six thousand of eight thousand Connecticut militia simply picked up and went home—and the longer he stayed in the city, the greater the danger he would be encircled and destroyed. At a war council on September 12, Washington accepted the advice of his officers to abandon all of Manhattan to the enemy except for Fort Washington at the northern end of the island. Greene (supported by John Jay, among others) argued strongly that New York should be burned as well as abandoned. (“That cursed town from first to last has been ruinous to the common cause,” exclaimed one officer.) Congress firmly rejected the idea. Two days later, leaving Putnam and five thousand men behind to cover his rear, Washington shifted his headquarters ten miles out of town to the home of Roger Morris on Harlem Heights (now the Morris-Jumel Mansion on 162nd Street).

On October fifteenth, the Howe brothers finally roused themselves for another move against Washington. That morning, Connecticut militiamen crouched in trenches a few miles above the city at Kip’s Bay (34th Street) observed so many flatboats of redcoats massing just across the East River at the mouth of Newtown Creek that it looked “like a large clover field in full bloom.” As they pushed off, five warships anchored nearby poured barrage after barrage into the American positions—“so terrible and so incessant a Roar of Guns few even in the Army & Navy had ever heard before,” declared Lord Howe’s secretary, Ambrose Serle. Awestruck spectators on the shore at Bushwick watched as four thousand British troops swarmed toward Manhattan to “the strains of exciting music, and the peals of thundering guns, the tall ships vomiting flames and murderous shot” under “rolling volleys of smoke.” The militia ran off in fear, and the British waded ashore without opposition. “The rogues have not learnt manners yet,” scoffed one of His Majesty’s officers; “they cannot look gentlemen in the face.” By early afternoon the British had taken possession of the Robert Murray farm—atop what is now Murray Hill—and were prepared to descend on the city below.

Washington, racing down from Harlem Heights, found his troops in complete disarray, “flying in every direction and in the greatest confusion.” He tried to rally them in a cornfield north of what is now 42nd Street, near where the Public Library now stands, but the sight of advancing redcoats sent them running again up the Bloomingdale Road (Broadway). At this, witnesses recall, Washington went berserk with rage. “The General was so exasperated,” a Virginia officer reported, “that he struck several officers in their flight, three times dashed his hat on the ground, and at last exclaimed, ‘Good God! Have I got such troops as those?’” Aides led him away, fearful he would be captured. The disgraceful rout became a more orderly retreat only after his panic-stricken soldiers reached McGowan’s Pass at the south end of Harlem Plains.

In the meantime, Howe arrived at the Murray farm and stopped to wait for reinforcements—or perhaps, according to legend, to have some cake and wine with Mrs. Murray, who saw a chance to distract him from the business at hand. Howe’s dallying gave Putnam and the rest of the army, guided by Lieutenant Aaron Burr, time to slip out of New York along the Greenwich Road and reach Harlem Heights before the redcoats crossed Manhattan to cut them off. They left behind about half of the army’s heavy guns and what Greene called “a prodigious deal of baggage and stores.”

The city itself was in a state of utter chaos as thousands of civilians, including the last remaining members of the Mechanics Committee, scrambled to get out as well. Only a few thousand remained when some officers from the fleet rowed ashore that evening to announce that New York was again in British hands. A small but delirious crowd of Tories paraded them “upon their shoulders about the streets and behaved in all respects, women as well as men, like overjoyed Bedlamites,” Ambrose Serle reported. “One thing is worth remarking,” he added: “A woman pulled down the rebel standard upon the fort, and a woman hoisted up in its stead His Majesty’s flag after trampling the other under foot with the most contemptuous indignation.”

The next day, September 16, a reconnaissance party of Connecticut rangers tangled with an advance column of several hundred redcoats on a farm near present-day 106th Street and West End Avenue. As the rangers pulled back toward the Hollow Way, a ravine where West 125th Street now meets the Hudson River, enemy buglers taunted them with the same call that traditionally ended a successful fox-hunt. “I never felt such a sensation before,” wrote Washington’s adjutant, Joseph Reed, who witnessed the retreat. “It seemed to crown our disgrace.” Perhaps even more sharply stung—no one appreciated better than Virginians the upper-class associations of fox-hunting—Washington ordered up reinforcements and counterattacked, driving the redcoats back through a buckwheat field in the vicinity of 120th Street and Broadway before breaking off the engagement two hours later. About thirty Americans and fourteen British had been killed. This “brisk little skirmish,” as Washington called it, was the first time soldiers under his command had bested the British in a stand-up fight; it did much to lift their flagging spirits.

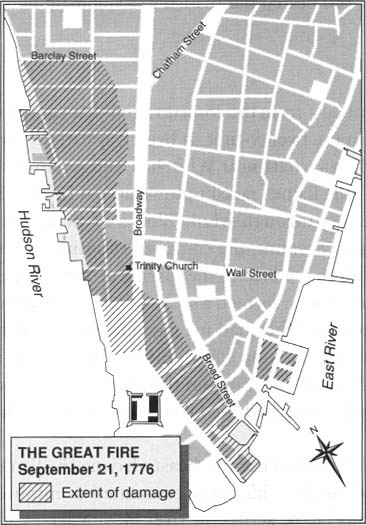

Patriot morale got another boost from the conflagration that engulfed the now-occupied city soon after midnight on the twenty-first. It began, apparently, in a tavern called the Fighting Cocks that stood on a wharf near Whitehall Slip. From there, driven by a brisk wind from the southwest, the flames raced uptown across Bridge, Stone, Marketfield, and Beaver streets, sweeping through whole blocks of houses and shops at a time. According to one newspaper account, the confused shouting of men and the terrified shrieks of women and children, “joined to the roaring of the flames, the crash of falling houses and the widespread ruin. . . formed a scene of horror great beyond description.” Clutching what few possessions they had managed to gather up, hundreds of people plunged through the heat and choking smoke toward the relative safety of the Common, “where in despair they fell cowering on the grass.” Far to the north, on Harlem Heights, Alexander Graydon watched the blaze grow until “the heavens appeared in flames.”

At two A.M. the wind shifted to the southeast, driving the flames across Broadway, then up toward Trinity Church, which was consumed in minutes. A contingent of rebels watching from Paulus Hook, across the river in New Jersey, cheered as its steeple collapsed in “a lofty pyramid of fire.” St. Paul’s, half a dozen blocks to the north, escaped a similar fate thanks to the efforts of a hastily organized bucket brigade. British soldiers and seamen were rushed in at daybreak to provide assistance, but not until the blaze reached the empty lots north and west of St. Paul’s, around midmorning, did it finally burn out. Smoldering in the mile-long swath of destruction were the ruins of better than five hundred dwellings, one-fourth of the city’s total.

Many jumped to the conclusion that the fire was the work of rebel arsonists. Furious mobs killed several suspicious characters during the night—one or two for carrying “matches and combustibles under their clothes,” another for “cutting the handles of fire buckets,” a couple of others for being “in houses with fire-brands in their hands.” Various eyewitnesses remembered other things as well: missing fire-alarm bells, broken fire engines and pumps, empty cisterns, and wagonloads of combustible materials concealed in cellars and basements.

Military authorities rounded up about two hundred men and women for questioning, among them a young captain in the American forces named Nathan Hale. Hale confessed that he had come to New York to spy on the British, and because he was out of uniform, General Howe had no choice under the rules of war but to have him hanged the next morning. Hale’s final words from the gallows (most likely located in an artillery park at today’s Third Avenue and 66th Street)—“I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country,” paraphrased from Addison’s play, Cato—made him famous but didn’t settle the question of whether he, or anyone else, had attempted to burn the city. Although no credible evidence of deliberate arson ever came to light, it was Washington who delivered the final verdict while studying the red glow on the horizon from the balcony of the Roger Morris house on Harlem Heights: “Providence, or some good honest fellow, has done more for us than we were disposed to do for ourselves.”

The clash on Harlem Heights convinced the ever cautious Howe to encircle the American army rather than attack head-on. On October 12, three weeks after the fire, he took four thousand redcoats up the East River to Long Island Sound and landed on a peninsula called Throg’s Neck (Fort Schuyler Park in the Bronx). Their task was to seize King’s Bridge, a few miles to the west and Washington’s only means of escape across the Harlem River to the mainland. A small party of riflemen gave the redcoats some trouble at Westchester Creek, however, and Howe decided to wait for reinforcements. He waited for six days, then put everybody back on the boats and shifted the attack three miles north to Pell’s Point (Pelham Bay Park), where a much smaller force of Americans held him up again on the road to the little hamlet of Eastchester. Washington, meanwhile, moved his army off Manhattan up to White Plains, leaving only a twelve-hundred-man garrison at Fort Washington.

Howe finally worked his way up through Eastchester and New Rochelle to White Plains, which he attacked and drove Washington out of on the twenty-seventh. Again he didn’t pursue the Americans, this time because he needed to return to Manhattan and deal with Fort Washington, which continued to threaten his communications with New York. On November fifteenth, following a heavy bombardment from British batteries on the east side of the Harlem River and a frigate anchored in the Hudson, about twenty thousand Hessians and redcoats converged on Washington Heights. After a brief struggle, the fort’s bedraggled and vastly outnumbered defenders surrendered. “A great many of them were lads under fifteen and old men, and few had the appearance of soldiers,” observed one British officer. “Their odd figures frequently excited the laughter of our soldiers.” Washington, who had meanwhile divided his army and taken part of it across the Hudson to New Jersey, watched in horror from Fort Lee as the last American forces on Manhattan were marched off into captivity. He wouldn’t set foot on Manhattan again for seven years.

The fall of New York didn’t doom the Revolution, as many on both sides had initially expected, but it did change matters profoundly. All told, the American army had taken a terrible beating trying to hold the city. Some thirty-six hundred men lay dead or wounded, and another four thousand, along with three hundred officers, were prisoners of the enemy. Thousands of others had simply gone home in disgust or despair. Mountains of ammunition and equipment had been lost.

This dismal accounting persuaded many army officers and members of Congress to think twice about the best way to carry on the struggle. Lee’s notion of relying on militia and home-grown amateur officers seemed discredited; Washington, among others, now believed the Revolution wouldn’t survive unless Congress created a standing army of regular, professional troops who obeyed their officers, held their ground under fire, and didn’t head for home whenever they wanted (to which Henry Knox added pleas for a military academy to provide the army with proper officers).

Similarly, the loss of Long Island in August and of Fort Washington in November appeared to demonstrate that the British couldn’t be beaten in a Bunker Hill-style confrontation. Instead, Washington decided, he would endeavor to keep the army intact, avoiding the big battle that could lose everything and concentrating instead on striking the smaller, sharper blows that would wear away the enemy’s resolve. Thus when Howe finally retired to New York City for the winter, Washington lashed back with surprise raids on the small British garrisons at Trenton and Princeton in late December and early January, two modest but morale-building victories.

Howe would receive the Order of Bath for capturing New York, but his foot-dragging was the subject of recurring controversy. In 1778, after the loss of Saratoga, he was recalled in favor of Clinton and Cornwallis, both of whom promised to be more aggressive generals. Fortunes also changed for the English radicals who between 1764 and 1776 had spoken out so vigorously on behalf of the colonies. With a few prominent exceptions, they were thrown off balance by the American demand for independence, for while they accepted it as a legitimate expression of the popular will, colonial self-determination would blast all hopes that reformers on both sides of the Atlantic could work together toward the same objective.

Republicanism, too, was a problem. By rejecting monarchy and aristocracy, by insisting on the primacy of reason over tradition and traditional authority, and indeed by at least asserting the principle of full political equality, the Americans had moved far beyond all but their most radical counterparts in Britain.

The outbreak of fighting, finally, dampened public enthusiasm for America. British merchants, fearful of the loss of trade, rallied behind the ministry and sent addresses of loyalty to the crown; British crowds turned increasingly patriotic, snapping the connection between radicalism and working-class discontent. Pottery manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood, a longtime supporter of colonial protest, observed ruefully that the town of Newcastle “went wild with joy” when word arrived that His Majesty’s army had captured New York. Even in London, once a stronghold of pro-American sentiment, there was a noticeable decline of enthusiasm for the rebel cause. Not for another generation, by which time the world had greatly changed, would British and American radicals again come within hailing distance of one another.