In May 1787 delegates from a narrow majority of the thirteen states met in Philadelphia to identify “defects” in the Articles of Confederation and propose such remedies “as shall appear to them necessary to render the constitution of the Federal Government adequate to the exigencies of the Union.” To represent New York, the state legislature had chosen Alexander Hamilton and two veteran Clintonians, Robert Yates and John Lansing, declaring that the three would attend “for the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation.” But when the Philadelphia Convention got down to work at the end of the month, it became apparent at once that the delegates were ready to draw up a brand-new frame of government for the United States.

Hamilton treated the convention to a remarkable five-hour lecture in which he confessed his admiration for the British system and proposed his own plan for a “completely sovereign” national government, all but eliminating the states and stipulating the election of a president and senate for life. But he realized that such notions “went beyond the ideas of most members,” and at the end of June, bored and irritated, he returned to New York. Yates and Lansing followed in short order, protesting that their instructions didn’t “embrace an idea of such magnitude as to assent to a general constitution.” In their absence, the convention proceeded to draft a federal constitution. Congress (still sitting in New York) officially transmitted the resulting document to the states, ratification by nine of the thirteen being required for it to take effect.

In New York, the proposed government faced an uphill fight. Advocates of ratification, now called Federalists, looked very strong among the wealthiest classes throughout the state and among all segments of the population in the city—thanks in no small part to Hamilton, who finally signed the Constitution as better than “anarchy and Convulsion.” In the rural upriver counties, however, home to the bulk of the state’s population and the heartland of Clintonianism, it was the “Antifederalists” who seemed unassailable.

Both sides rehearsed their arguments in a heated newspaper and pamphlet war that began in the summer of 1787 and raged for the better part of a year. Hundreds of essays and pamphlets and broadsides, for as well as against ratification, would be published in the city, and no one, it seemed, could talk of anything else. Apologizing to readers who wanted “NEWS, as well as POLITICS,” Thomas Greenleaf of the New-York Journal explained that “the RAGE of the season is, Hallow, damme, Jack, what are you, boy, FEDERAL or ANTI-FEDERAL?” (There were now half a dozen papers published in the city. Francis Childs’s Daily Advertiser, founded in 1785, appeared daily, only the third paper in the country to do so. The New York Morning Post, founded in 1783, became a daily in 1786. John Holt’s New-York Journal, taken over by Greenleaf early in 1787, briefly became a daily in 1787—88 because Greenleaf said he would otherwise be unable to print half of the essays he received supporting or opposing the Constitution.)

Antifederalist opinion drew heavily on the radical Whig conviction that concentrated power was a menace to liberty. Under the Constitution, Antifederalists charged, the federal government’s broad prerogatives—to tax, to raise armies, to regulate commerce, to administer justice—would sooner or later overwhelm the states, pulverize individual rights, and sink the republic under a mass of corruption. Then, too, large republics had always succumbed to tyrants or dissolved in civil war. The great diversity of the American people, to say nothing of the distances separating them, offered no reason to hope that the United States could escape a similar fate.

Under the Constitution, Antifederalists also stressed, Congress would be too small and too remote from the people to represent them effectively. The widely circulated Letters from the Federal Farmer, a pamphlet that first appeared in November 1787 (probably written by Melancton Smith), stressed the inadequacy of representation under the Constitution. “Natural aristocrats” and demagogues, it argued, would have a better chance of winning election to Congress than men drawn from “the substantial and respectable part of the democracy.” No wonder, other Antifederalists said knowingly, that the Constitution was supported by the rich and well-born few.

Federalists, defending the Constitution, asserted that under the Articles of Confederation the country was falling apart. While Congress looked on helplessly, violent factionalism and insurrection had afflicted one state after another—most recently Massachusetts, where insurgent farmers led by Daniel Shays had closed courts in the western part of the state and in January 1787 mounted an abortive attack on the federal arsenal at Springfield. Trade and commerce meanwhile continued to languish, public credit had evaporated, and Congress, powerless to defend its own interests against foreign nations, had become an international laughingstock. The Constitution would end this misery by establishing a stronger, more energetic national government—which of course, Federalists said, explains why it had met with such opposition from popular demagogues and state politicians fearful of losing influence.

Toward the end of October 1787, the Independent Journal ran the first of eighty-five essays by “Publius.” Published together the following May as The Federalist, they were the fruit of a brilliant collaboration between Hamilton, Jay, and Congressman James Madison of Viriginia. Their exhaustive, clause-by-clause defense of the Constitution remains the most famous contribution to the debate on either side and a landmark of American discourse on government. Two crucial arguments of The Federalist, both related to the issue of representation, would have seemed especially compelling to readers in New York.

First, under the Articles of Confederation too many decisions of national importance depended on state governments that had been taken over by the wrong sort of men: men unprepared by wealth or education to conduct public business, “men of factious tempers, of local prejudices, or of sinister designs . . . [who] practice with success the vicious arts by which elections are too often carried”—exactly the kind of “democratical” leaders, in other words, who had followed George Clinton into office in New York after 1776. But the Constitution would set things right by causing an “ENLARGEMENT of the ORBIT” of government sufficient to exclude from power all but the “proper guardians of the public weal.” Congress, having powers commensurate with its responsibilities, would draw more “fit characters” into public life, and large electoral districts would ensure the election of those “who possess the most attractive merit and the most diffusive and established characters”—which was, of course, the very thing that worried the Antifederalists.

Second, it was wrong to think that these “diffusive and established characters”—in New York City, this meant the merchant elite—would be unable to comprehend “the interests and feelings of the different classes of citizens.” They had to stand for election, after all, and would always want to pay close attention to the “dispositions and inclinations” of the voters. Also, by virtue of their ties to all segments of the laboring population, merchants had a very clear picture of what was good for the mass of their fellow citizens. Indeed, honest tradesmen knew that “the merchant is their natural patron and friend; and they are aware, that however great the confidence they may justly feel in their own good sense, their interests can be more effectually promoted by the merchant than by themselves. They are sensible that their habits in life have not been such as to give them those acquired endowments, without which, in a deliberative assembly, the great natural abilities are for the most part useless.”

But for many New Yorkers it was a third contention of The Federalist that must have clinched the case: ratification of the Constitution was indispensable to their future prosperity. By giving Congress the exclusive power to regulate foreign commerce, “Publius” declared, the Constitution would permit the United States to extract “commercial privileges of the most valuable and extensive kind” from Great Britain—above all to reopen the lucrative West Indian markets that had anchored the city’s economy before independence. Similarly, allowing Congress to create a navy “would enable us to bargain with great advantage for commercial privileges” in the event of war between European nations; it would also provide employment for seamen as well as for the many artisans engaged in building and outfitting ships. A string of other powers bestowed on Congress—to borrow and coin money, to establish post offices, to fix the standard of weights and measures, to make uniform laws of bankruptcy—would meanwhile remove annoying obstacles to the expansion of domestic markets. The only alternative to ratification, in fact, was national ruin. “Poverty and disgrace would overspread a country which, with wisdom, might make herself the admiration and envy of the world.”

By January 1788, when the regular session of the legislature got underway, five states—Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Georgia, and Connecticut—had ratified the Constitution, and conventions were deliberating in several others. After stalling for several weeks, the Clintonian legislature called for a ratification convention to meet in Poughkeepsie in mid-June. The election of delegates would take place at the end of April. Each county would send as many delegates as it had assemblymen. And—in an unusual but noncontroversial move—existing property requirements would be waived so that all free male citizens aged twenty-one and over would be entitled to vote.

During February and March upstate Antifederalists organized a network of county committees that distributed literature, nominated candidates, and aroused voters in anticipation of the election. In New York City, though, they moved hesitantly at best. Public opinion there was running strongly in favor of the Constitution, and news that Massachusetts had ratified in early February was greeted with spontaneous demonstrations and a parade. John Lamb, Melancton Smith, Marinus Willett, and other city Antifederalists finally set up a committee in April, but it stuck to dispatching essays and pamphlets to Antifederalist committees throughout the northeast and didn’t even bother to get up a proper municipal ticket for the Poughkeepsie convention. Most of the key Manhattan leaders put their names up in Ulster, Dutchess, and Queens counties, where they were almost certain of victory. By contrast, the New York City “Federal Committee” pulsed with activity. It got up an impressive slate of candidates, including John Jay, James Duane, and Alexander Hamilton, and had its slate endorsed by special meetings of the “German inhabitants,” the “Master Carpenters,” a group of “Mechanics and Tradesmen,” and the St. Andrew’s Society, among others.

When the votes were tallied at the end of April, Antifederalists came out well ahead statewide. Queens went Antifederalist by a five-to-four margin. Kings, Richmond, and Westchester came in solidly Federalist. Manhattan produced a Federalist landslide: all told, 2,836 men went to the polls there—the highest turnout thus far in the city’s history—and John Jay paced the Federalists with 2,735 votes, an impressive 96 percent of the total. Nicholas Low, who trailed the ticket, got 2,651. Governor Clinton received a paltry 134 votes, and Marinus Willett and William Denning garnered just 108 and 102 votes, respectively. Willett, chastened, was said to be coming round to the view that the Constitution “might be right—since it appears to be the sense of a vast majority.”

The convention thus promised a face-off between rural and urban forces, and between delegates whose backgrounds differed in other ways as well. Federalists were predominantly merchants, lawyers, former officers in the Continental Army, Anglicans, socially prominent, well-off, and college educated; most had had experience in high public office. Antifederalists were mostly older than their counterparts and had entered politics later in life. They were the “new men” associated with Governor George Clinton: farmers, rising entrepreneurs, sometime militia officers, Presbyterians, self-educated, self-made, radical Whig in outlook, and utterly lacking the social connections and graces that had been essential to political advancement before the Revolution.

On Saturday, June 14, 1788, while crowds cheered and cannon boomed, New York’s delegates to the ratifying convention boarded Hudson River sloops for the village of Poughkeepsie, seventy-five miles upriver. Governor Clinton and his party left later the same day, almost unnoticed. When the convention got underway in the village courthouse the following Tuesday, however, Clinton had a happier time of it. The Antifederalist majority, obviously in control, settled him in the chair and had two staunch opponents of the Constitution appointed secretaries.

The outnumbered Federalists weren’t without resources, even so. Alexander Hamilton, Robert R. Livingston, and John Jay were three of the foremost orators in the nation. Of them one observer remarked: “Hn’s harangues combine the poignancy of vinegar with the smoothness of oil: his manner wins attention; his matter proselytes the judgment. . . . L pours a stream of eloquence deep as the Ganges. . . . Mr. Jy’s reasoning is weighty as gold, polished as silver, and strong as steel.” Melancton Smith readily admitted that the Federalists had all the “advantages of Abilities and habit of public speaking.”

Time was now on the Federalists’ side too. Eight states had already ratified the Constitution, and conventions in two more, New Hampshire and Virginia, were in session. Ratification by either one would be sufficient to dissolve the old Confederation and launch the new federal union. All the Federalists in New York had to do was keep the opposition from bringing the issue to an early vote. They thus scored an important tactical victory of their own on the opening day when the convention agreed to discuss the Constitution clause by clause before deciding whether to ratify.

Six days later, on June 25, express riders reached New York City and Poughkeepsie with word that New Hampshire had ratified. In Poughkeepsie the Antifederalists insisted that the news didn’t upset their calculations—without Virginia, they reminded everyone, federal union remained highly problematic—but Virginia, it soon turned out, had ratified that very day. The news got to New York City at three o’clock in the morning of July 2. Bells began to peal and continued until dawn, when ten twenty-four-pounders fired a loud salute to the new government. William Livingston, who had set out immediately for Poughkeepsie, galloped up to the courthouse around noon the same day and burst in upon the convention with the story. Federalist delegates cheered, and spectators paraded around the building with fife and drum. With only New York and Rhode Island now out of the Union, it seemed certain that the Antifederalists would accept the inevitable and vote for the Constitution.

They didn’t. Rallied by Smith, the Antifederalists put forward a plan for limited or conditional ratification: they would agree to the Constitution providing that, within a specified period of time, a “bill of rights” was added to safeguard freedom of the press, freedom of conscience, and other individual liberties. If the desired amendments failed to materialize, the state would withdraw its ratification. Hamilton and the Federalists denounced the idea, contending that it would cause more trouble and confusion than outright rejection of the Constitution. The Antifederalists were adamant, however, and for another several weeks it remained unclear what the convention would do.

Down in New York City, the Antifederalists’ demand for a bill of rights raised a hurricane of indignation, not least of all because Congress had already started talking about where to go if the Poughkeepsie convention failed to ratify the Constitution. “You have no idea of the rage of the Inhabitants of this City,” Samuel Blachley Webb wrote a friend, adding that if ratification did not happen soon, “I do not believe the life of the Governor & his party would be safe in this place.”

Many people suggested that the city should secede from the state and ratify the Constitution separately. Newspapers in Pennsylvania and Connecticut as well as New York carried reports that Richmond, Kings, Queens, Suffolk, and Westchester counties were also prepared to cast their lot with a new state if the convention failed to ratify. There was speculation about the likelihood of civil war, and when John Lamb led a party of Antifederalists down to the Battery to burn a copy of the Constitution, they had to fight their way out of the angry crowd that surrounded them.

Federalist spokesmen in Poughkeepsie reminded the opposition that Congress was important to the city and that the city was indispensable to the state. Jay told the convention that Congress pumped a hundred thousand pounds a year into the municipal economy. In fact, he said, “All the Hard Money in the City of New York arises from the Sitting of Congress there.” Chancellor Livingston worried that the state’s isolation from the Union would be economically ruinous and raised the possibility that “the Southern part of the State may separate.”

Hamilton went further: a separation was inevitable, he warned, if New York rejected the Constitution. Although Governor Clinton reprimanded Hamilton from the chair for this “highly indiscreet and improper” threat, Antifederalists were now clearly worried about the mood of the city.

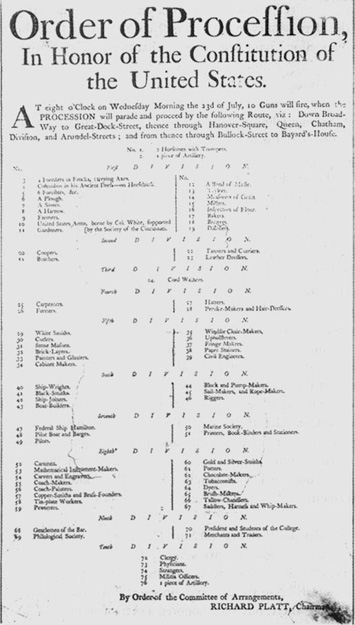

It was in this setting that city Federalists mounted a “Grand Federal Procession” to celebrate the Constitution. Similar events had been staged in Boston, Philadelphia, Charleston, and other cities, and during June, if not earlier, arrangements were underway for something equivalent in New York. Originally scheduled to coincide with the city’s Fourth of July festivities, the New York procession was repeatedly postponed because its organizers kept waiting for word of ratification from Poughkeepsie. Finally, their patience at an end, they called for participants to assemble in the Common at eight o’clock on the morning of July 23.

Five thousand men and boys representing sixty-odd trades and professions showed up despite a light drizzle, all in costume and accompanied by colorful floats and banners proclaiming the happiness and prosperity that would follow from stronger national union. The Bakers, positioned near the front of the column by white-coated assistants with speaking trumpets, held aloft a ten-foot “federal loaf” and “a flag, representing the declension of trade under the old Confederation.” After them came the other trades with banners proclaiming the certain return of prosperity under the new government. “May we succeed in our trade and the union protect us!” declared that of the Peruke Makers and Hair Dressers; further down the line of march were the Black Smiths, hammering away on an anchor and chanting: “Forge me strong, finish me neat, I soon shall moor a Federal fleet.”

Towering over every other display was the “Federal Ship Hamilton” in the Seventh Division. A scaled-down thirty-two-gun frigate, twenty-seven feet in length, it rumbled along behind a team of ten horses “with flowing sheets, and full sails .. . the canvass waves dashing against her sides, the wheels of the carriage concealed.” A “federal ship” had figured in similar processions elsewhere, but none honored a specific individual. Its preeminent role in the New York proceedings was dramatic testimony to Hamilton’s effectiveness in linking adoption of the Constitution to the city’s economic well-being. As the nearby banner of the Ship Joiners proclaimed: “This Federal Ship Will Our Commerce Revive / And Merchants and Shipwrights and Joiners Will Thrive.” There was even talk that day of renaming the city “Hamiltoniana” in his honor.

The marchers headed down Broadway to Great Dock Street, where the Hamilton exchanged salutes with a Spanish packet, then swung over to Hanover Square and moved through Queen, Chatham, and Arundel streets to Bayard’s Tavern on Bullock Street. The Committee of Arrangements, members of Congress, and “the Gentlemen on Horseback” reviewed the marchers outside the tavern, and the Hamilton changed pilots to guide it from the “Old Constitution” to the new. More cannon were fired. Everyone then sat down to a banquet at tables set up around a canvas pavilion designed by a French architect, Major Charles Pierre L’Enfant. After a feast of roast ham, bullock, and mutton, the day-long festivities concluded with a toast to “the Convention of the State of New York; may they soon add an eleventh pillar to the Federal Edifice.”

Artisans dominated the first eight “divisions” in the line of march, followed by lawyers, merchants, and clergy—testimony not only to the depth of support for the Constitution among working people, but also to the importance of the organized trades in the public life of the city after Independence. (© Collection of The New-York Historical Society)

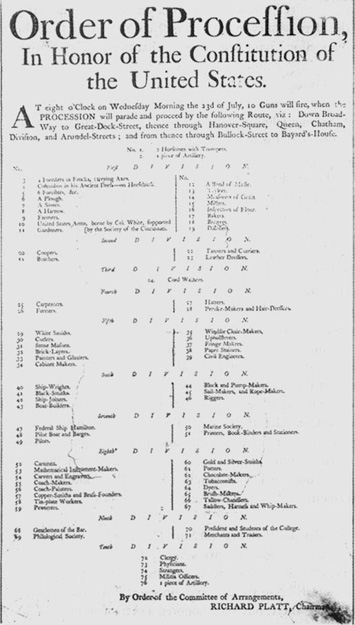

Antifederalists scoffed and sneered, but the Grand Federal Procession was an event of almost transcendent significance in New York’s post-Revolutionary history. Nominally, it dramatized the breadth of local support for the Constitution and, by implication, the city’s determination not to be left out of the new federal union. No less important, arguably even more so, the massed presence of the trades also gave tangible expression to the organized artisanal presence that was already altering the course of municipal affairs. After two decades of upheaval and war, New York’s numerous mechanics had come to see themselves as equal citizens, actively engaged in the life of the community. Their best qualities—their respect for labor, their selfless interdependence, their usefulness to society, their unflinching patriotism—were the very essence of republican virtue.

Up in Poughkeepsie, the Antifederalists had already decided to surrender. That morning, even as the marchers were moving out of the Fields, Samuel Jones, the Queens Antifederalist, made a motion to ratify the Constitution “in full confidence” that a bill of rights would be forthcoming. Melancton Smith supported the motion, explaining that he feared the consequences if New York spurned the Union—“Convulsions in the Southern part, factions and discord in the rest.” Jones’s motion passed. The Federalists, in turn, accepted thirty-two “recommendatory” and twenty-three “explanatory” amendments to the Constitution and agreed to urge a second convention to consider them. A final vote next day produced a margin of thirty to twenty-seven for ratification—the narrowest in any state.

Silk banner carried by the Society of Pewterers in the Federal Procession. (© Collection of The New-York Historical Society)

An express rider carried the news down to New York City on the evening of the twenty-sixth. Jubilant crowds again surged through the streets. One group ransacked the office of Greenleaf’s Antifederalist Journal and made off with his type. Another paraded over to Governor Clinton’s residence, gave three hisses, and beat the rogue’s march; there was talk of going after John Lamb as well, but nothing came of it. More commotion followed a few days later when the Federalist delegation returned from Poughkeepsie. Cheering crowds greeted them at the waterfront, and eleven-gun salutes were fired before each of their houses.

At the end of the summer of 1788, the Confederation Congress designated New York City as the temporary seat of the new federal government. Both it and the City Council then vacated City Hall so the building could be converted into a suitable capitol by L’Enfant. He gave it a complete facelift and turned its interior into a showcase of plush, some said extravagant, neoclassicism. In November, as elections for the new government got underway, the old Congress adjourned for good, leaving the country with no central government for the next five months.

L’Enfant’s work was substantially complete by March 4, 1789, when the new Congress convened in what was now Federal Hall—over which, in honor of the occasion, flew the flag of the “Federal Ship Hamilton.” After waiting anxiously for a month to get quorums, the Senate and House were at last able to count the ballots cast by presidential electors. To no one’s surprise, George Washington was the unanimous choice. Genuinely dismayed by the news, Washington left Mount Vernon for New York in mid-April, hoping to have “a quiet entry to the city devoid of ceremony.” He felt, he said, like “a culprit who is going to the place of his execution.”

His week-long journey to Manhattan proved anything but quiet. Every town, village, and hamlet marked the president-elect’s passage with ecstatic crowds, honor guards, booming artillery, ringing church bells, banquets, speeches, triumphal arches, and rose-strewn streets. New York churned with anticipation. “All the world here are busy in collecting flowers and sweets of every kind to amuse and delight the President in his approach and on his arrival,” one man wrote. Washington portraits went up everywhere. The initials G. W. appeared on front doors, buttons, and tobacco boxes. Local taverns and boardinghouses were besieged by excited visitors, many of whom had to settle for lodgings in nearby villages and campgrounds.

On April 23, Washington entered Elizabethtown, New Jersey, where an official welcoming committee from New York (Robert R. Livingston, Richard Varick, Egbert Benson) was waiting in a red-canopied barge to escort him across the Hudson River. As the barge pulled away from the New Jersey shore, rowed by thirteen harbor pilots in sparkling white uniforms, it was surrounded by a dense mass of vessels, one of which bore musicians and a chorus whose voices were barely audible above the roar of cannon from shore batteries and a Spanish warship in the harbor. One witness, who watched the barge pass the Battery, commented that the “successive motion of the hats” of cheering bystanders “was like the rolling motion of the sea, or a field of grain.” Governor Clinton and Mayor Duane greeted Washington at Murray’s Wharf at the foot of Wall Street on the East River. Clinton said a few words, which almost nobody could hear over the din, and then, preceded by a military guard and two marching bands, escorted Washington up Wall Street through throngs of well-wishers. Turning into Pearl Street, the procession moved slowly along to Cherry Street and the Presidential Residence, a private mansion that had been handsomely refurbished at a cost of twenty thousand pounds (all of it raised by private contributions).

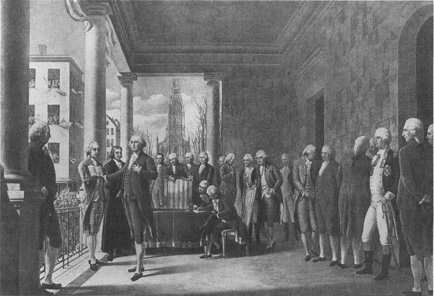

Thursday, April 30, was Inauguration Day, and the city awakened at dawn to a salute from the guns on the Battery. At nine o’clock, hour-long services got under way in all churches. Congress assembled at noon and dispatched a party of dignitaries to fetch the president-elect from his Cherry Street residence. After some inevitable confusion over the formalities—there were no precedents to rely upon, after all, and nobody remembered to bring a Bible—Washington stepped out on the second-floor balcony of Federal Hall, dressed for the occasion in a plain suit of “superfine American Broad Cloth” from a mill in Hartford, Connecticut. He hoped, he had said, that it would soon “be unfashionable for a gentleman to appear in any other dress” than one of American manufacture.

“The scene was solemn and awful beyond description,” wrote one spectator. Chancellor Livingston administered the oath of office, then, overcome by emotion, bellowed, “Long Live George Washington, President of the United States!” The densely packed crowd below responded with “loud and repeated shouts” of approval, and Washington went back inside to deliver his inaugural address. Afterward, he and the members of Congress walked up to St. Paul’s on Broadway for a worship service.

That evening, visitors and residents jammed the streets to gawk at “illuminations”—huge backlit transparent paintings of patriotic subjects erected here and there around the city. One, at the lower end of Broadway, showed Washington with the figure of Fortitude, flanked by the Senate and House and surmounted by the forms of Justice and Wisdom. Another, displayed at the John Street Theater, showed Fame descending from heaven like an angel to bestow immortality on the new President. Even the residence of the Spanish minister was bedecked with moving transparencies that depicted the past, present, and future glories of America. Bands played, houses and ships in the harbor blazed with candles, and the skies above crackled with a two-hour-long display of fireworks. Washington, who watched the show from Chancellor Livingston’s house, had to get home on foot because the streets were too full of people for his carriage to pass.

Inauguration of General George Washington as President, 1789. Engraving by Montbaron & Gautschi. (© Collection of The New-York Historical Society)