New York had been the de facto capital of the nation since 1785, but the transition from Confederation to Constitution gave new snap and sophistication to life in the city. Trailing behind President Washington came a multitude of Revolutionary heroes and near-heroes—“the most celebrated persons from the various parts of the United States,” as the French reformer Brissot de Warville wrote in his New Travels in the United States (the first American edition of which appeared in New York in 1792). A brief stroll through the streets of lower Manhattan could bring residents face to face with Vice-President John Adams, Secretary of War Henry Knox, Attorney General Edmund Randolph, Congressman James Madison, or Senator John Hancock; Thomas Jefferson, currently American ambassador to France, would arrive in another six months or so to take up his duties as secretary of state. So many of the republic’s most famous men converged on New York over the spring and summer of 1789 that the painter John Trumbull moved to the city in December to finish the portraits on his monumental canvas The Declaration of Independence.

Washington drew numerous prominent New Yorkers into the new federal orbit. John Jay became the first chief justice of the Supreme Court. Alexander Hamilton was named secretary of the treasury on the recommendation of Senator Robert Morris (Hamilton was “damned sharp,” Morris told Washington, who surely knew it already); Hamilton in turn chose William Duer for assistant secretary of the treasury. Gouverneur Morris took the post of ambassador to France, General John Lamb became collector of the port, and Richard Harison got the office of U.S. attorney. Chancellor Livingston thought he deserved a cabinet-level appointment but came up empty-handed—the only notable New Yorker to be snubbed by the administration. Although James Duane wanted to join General Philip Schuyler in the Senate, Governor Clinton arranged for the selection of Rufus King, a well-connected Massachusetts politician who had just moved down to the city. Instead, Duane got the job of first judge of the federal district court of New York. Richard Varick took over as mayor.

Municipal and state officials did their best to accommodate the federal government’s need for space and quiet deliberation. Congress complained that the ringing of bells at funerals disturbed its deliberations; local authorities obligingly banned the practice. The chief executive’s hemorrhoids flared up, and his doctors insisted that he stay in bed for six weeks; a chain was stretched across the street outside his residence to reduce the clatter of traffic. Additional renovations were required on Federal Hall; officials organized a lottery to raise seventy-five hundred pounds.1

There was even talk about turning lower Manhattan into the federal district envisioned in the Constitution, complete with government offices, residences, parks, and gardens; one plan designated Governors Island, just across the harbor, as the site for a presidential mansion. Eager to cooperate, the city demolished the old Anglo-Dutch fort on the Battery over the summer of 1789, uncovering, among other things, the coffin of Lord Bellomont and the cornerstone of the church erected during Willem Kieft’s regime a century and a half earlier. Once the fort was down, workmen began construction of a three-story brick building with ample quarters for all three branches of the government. When finished two years later, Government House, as it was called, commanded spectacular harbor views and an elegant waterfront promenade.

Provisions were dear and housing hard to come by, as ever, but New York’s cosmopolitan attractions made up for a good deal of discomfort. As wide-eyed St. George Tucker of Virginia recorded in his diary, the “hurly burly and bustle of a large town” held a unique fascination of its own. “You may stand in one place in this City and see as great a variety of faces, figures, and Characters as Hogarth or Le Sage (author of Gil Bias) ever drew.”

There were plenty of other things to do, however. Opposition to playhouses had receded again, and Lewis Hallam the younger had reopened the John Street Theater with a performance of Royall Tyler’s The Contrast, a sentimental comedy set in postwar New York. A new racetrack, the Maidenhead, was now operating just behind the old De Lancey mansion, and two new pleasure gardens had appeared: Brannon’s, near the southwest corner of present Spring and Hudson streets, and the United States, an establishment on Broadway once run by the widow Montayne. Much frequented by students from Columbia College, Brannon’s was renowned for its “curious shrubs and plants” and excellent ice cream; the United States pitched its advertisements to the “Fair Sex” and noted that “select companies or parties, can always have an apartment to themselves, if required.”

But would the federal government stay? The selection of a permanent site for the national capital remained a topic of passionate controversy around the country, New York being a far from popular choice. Its raw juxtapositions of wealth and poverty, its preoccupation with commercial profit, its tolerance (even laxity) in matters of religion and morality, its raucous crowds—none of these recommended the city to the nation’s overwhelmingly rural and agricultural population. Leading the opposition were hard-shell republicans who feared that New York’s “British” and “aristocratic” tendencies, to say nothing of its fleshpots, would sooner or later fatally corrupt the leaders of a free people. Everything they heard or saw over the next couple of years convinced them the end was already in sight.

Much would be made of Brissot’s observation that “if there is one city on the American continent which above all others displays English luxury, it is New York, where you can find all the English fashions.” One evening at dinner he encountered two ladies in “dresses which exposed much of their bosoms. I was scandalized by such indecency in republican women.” And was it really true, as a horrified Senator William Maclay of Pennsylvania reported, that many New Yorkers still observed the King’s Birthday “with great festivity”? Or what about Mrs. John Jay, the former Sarah Van Brugh Livingston, handsome and high-spirited daughter of William Livingston (long-ago editor of the Independent Reflector and later revolutionary governor of New Jersey)? She had married Jay in 1774, accompanied him on his diplomatic missions to Spain and France (becoming a favorite of Parisian society), and had now made their house on lower Broadway the center of New York’s smart society. Had she actually thrown her doors open to Lady Kitty Duer, Lady Mary Watts, Lady Christiana Griffin, and other American matrons not yet reconciled to republican forms of address? And what manner of idolatry prompted the Common Council to hire John Trumbull to paint a portrait of Washington for City Hall? (“Flattery to the living rulers is always dangerous,” scolded “Vox Res Publica.”) If Thomas Jefferson is to be believed, when he arrived to take up his duties as secretary of state in the spring of 1790 he was the only republican in town.

Very worrisome indeed, notwithstanding the suit of plain brown broadcloth in which Washington took the oath of office, was the courtly style of entertaining adopted by the chief executive and his wife. His Tuesday afternoon levees and her Friday evening receptions were, as one observer wrote, “numerously attended by all that was fashionable, elegant, and refined in society; but there was no places for the intrusion of the rabble in crowds, or for the more coarse and boisterous partisan—the vulgar electioneer—or the impudent place-hunter—with boots and frock-coats, or round abouts, or with patched knees, and holes at both elbows. . . . Full dress was required of all.” When the president appeared in public, it was noted, bands sometimes struck up “God Save the King.” His lady, it was noted, always returned visits on the third day, preceded by a footman.

Not overlooked, either, was the president’s cream-colored coach, drawn by a team of six horses—reputedly the finest equipage in the city—or the “bountiful and elegant” dinners served up by Samuel Fraunces, now the president’s head steward, who also supervised a household staff of twenty servants, maids, housekeepers, cooks, and coachmen. It didn’t help that in 1790 Washington moved his official residence from Cherry Street to the mansion built by Alexander Macomb at Number 39 Broadway, an even grander house at a better address. The rent was a breathtaking twenty-five hundred dollars per year. To the Boston Gazette, New York was a “vortex of folly and dissipation” into which republican virtue and simplicity had long since vanished.

New York’s champions, numerous and articulate, pooh-poohed all the commotion. Oliver Wolcott (related to the Livingstons, after all) made the city sound like a bastion of propriety: “There appears to be great regularity here,” he testified; “honesty is as much in fashion as in Connecticut; and I am persuaded that there is a much greater attention to good morals than has been supposed. So far as an attention to the Sabbath is a criterion of religion, a comparison between this city and many places in Connecticut would be in favor of New York.” Other advocates of the city emphasized its beauty and temperate climate (notwithstanding an influenza epidemic and heat wave in 1789 that resulted in numerous fatalities). According to one newspaper, only a single member of Congress fell ill while in New York—a point that became the subject of an extended commentary by Dr. John Bard, a local physician and president of the Medical Society, who pronounced New York “one of the healthiest cities of the continent.” The proof of this assertion, he said, was readily visible “in the complexion, health and vigor of its inhabitants.”

What couldn’t be shrugged off so easily was New York’s growing notoriety as a cauldron of financial speculation. Over the previous half-dozen years, “moneyed men” throughout the United States, often as not in league with European financiers, had come to think of heavily depreciated state and Continental securities as good investments. (As early as 1786, William Duer owned sixty-seven thousand dollars’ worth of Continental paper outright, and another two hundred thousand in partnership with half a dozen other New York investors.) If the American experiment in self-government succeeded, they reasoned, the value of their holdings would be multiplied many times over. The tempo of speculation quickened in the months before Washington’s inauguration, as investors became more and more certain that the new federal government would take immediate steps to put the nation’s finances in order.

New York afforded speculators two advantages. Rapid population growth—and above all a stream of immigrants with cash, credit, and connections—favored the city with an abundance of capital. “More money is to be had in Your City” than anywhere else in the country, a Philadelphia merchant complained to Andrew Craigie in 1789. As the national capital, furthermore, New York churned with valuable rumors, tips, and inside information that took days, even weeks, to reach buyers and sellers elsewhere. There was no substitute for rubbing elbows with important people in the government on a day-to-day basis, Craigie said. “I know of no way of making safe speculations but by being associated with people who from their Official situation know all the present & can aid future arrangements either for or against the funds.”

The early summer of 1789 brought word that southern state securities were both cheap and plentiful, some selling for as little as ten cents on the dollar. Over the next six months, seventy-odd New Yorkers scooped up $2.7 million worth of South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia obligations—roughly a third, all told, of their outstanding debts. Leading the pack was the firm of Herman LeRoy and William Bayard, with a combined investment of over $580,000. Andrew Craigie and four others were each in for a hundred thousand dollars or more. William Constable, another participant, told an English investor that “those in the secret” expected to come away with huge profits in the very near future. “My opinion is founded on the best information,” he wrote. “I cannot commit to paper my reasons, nor explain from whence I have my information, but I would not deceive you.”

Constable’s “secret” was that Treasury Secretary Hamilton (“our Pitt,” Constable called him reverently) would soon go before Congress with a financial plan calculated to boost the value of state and federal securities. How did Constable know? No evidence exists that Hamilton breached the confidentiality of his office. Assistant Treasury Secretary Duer, on the other hand, talked freely to Constable and their other New York friends and was himself deeply involved in speculation. Hamilton surely knew of Duer’s activities and did nothing—which encouraged the widespread suspicion that he was masterminding a corrupt conspiracy against the republic.

The denouement came in mid-January 1790, when Congress received from Hamilton a fifty-page Report Relative to Public Credit. According to Hamilton’s figures, the unpaid foreign and domestic debts of the United States amounted to some fifty-four million dollars. Outstanding state debts came to another twenty-five million. The total—nearly eighty million dollars—was the country’s “price of liberty,” Hamilton said. Yet, he added, neither the old Confederation nor many of the states had fulfilled their duty to pay off this sacred debt as promised. The annual revenues of the new federal government weren’t even enough to cover the interest on the debt (currently around $4 million a year), let alone retire the principal, and numerous public creditors had been waiting for their money for years. This intolerable negligence had brought the nation to a “critical juncture” in its history. Not only was “the individual and aggregate prosperity of the citizens of the United States” in jeopardy, but their very “character as a People” and “the cause of good government” hung in the balance as well.

No one in Congress opposed paying the national debt. At issue was who owed how much to whom, and where the money would come from. Hamilton’s recommendation followed what he, Robert Morris, and other conservative nationalists had been advocating for a decade or more. First, Congress should consolidate the various foreign and domestic debts incurred by both the confederation and federal governments since 1776 and “assume” (i.e., take responsibility for) unpaid state Revolutionary debts, with accumulated interest. Second, it should “fund” the whole amount “at par” (i.e., face value), meaning that it would provide sufficient revenue to pay the interest and part of the principal every year. As to the mechanics of the process, Hamilton gave Congress a choice of six different plans. The one eventually chosen called for state and federal creditors to exchange their old notes for new 6 percent federal “stock.” Accumulated interest, if any, would be paid in 3 percent stock.

Without funding and assumption, Hamilton reasoned, the United States could never achieve the stability, prosperity, and strength it needed to survive. As in Britain a century earlier, the creation of a funded national debt would restore the government’s credit among those persons, at home and abroad, who possessed “active wealth, or in other words . . . monied capital.” The assumption of state debts, Hamilton continued, would bind every public creditor to the new federal system by powerful “ligaments of interest.” If it succeeded, they would profit; if it failed, they would lose. Politically, in other words, funding and assumption together would cement the union by enhancing the authority and reputation of the central government vis-a-vis the states. Economically, too, funding and assumption would do wonders for the country. Public confidence in government stock would enable it to function like money, thereby increasing the money supply, driving down interest rates, and stimulating the development of agriculture, commerce, and industry.

No sooner had Hamilton’s report become public knowledge, Chancellor Livingston reported sourly, than a mania for speculation in public securities immediately “invaded all ranks of people.” New York went wild. Even prominent Antifederalists like George Clinton and Melancton Smith took the plunge. Big investors became celebrities. Stories circulated of their high-stakes derring-do, richly embroidered with talk of secret couriers and chests full of cash.

Prince of the New York speculators was none other than William Duer. After less than six months on the job, Duer abruptly resigned from the treasury—“I have left to do better,” he explained—and promptly threw himself into daring and complex schemes. Through his wide network of connections in the United States and Europe, he arranged for or encouraged the influx of millions of dollars from investors in Boston, Philadelphia, Amsterdam, Paris, London, and elsewhere. Suddenly one of the richest men in the country, he lived like an Eastern potentate in the former Philipse mansion, attended by a regiment of servants and fawned over by important visitors. Jefferson called him “the king of the alley.” The Rev. Manasseh Cutler, who attended one of the chic dinner parties given by Duer and his wife, the former Kitty Alexander, had never seen anything like it. “I presume he had not less than fifteen different sorts of wine at dinner, and after the cloth was removed, besides most excellent bottled cider, porter, and several other kinds of strong beer.”

Outside New York, and to no small degree because of the financial delirium there, Hamilton’s proposals roused fiery resentment. Funding at par, by allowing creditors to swap depreciated obligations for new interest-bearing paper at face value, was legalized fraud, critics said. Speculators with money and inside information—for surely Hamilton was in cahoots with Duer and other New York speculators—were raking in immense unearned profits at the expense of patriotic republicans who had been tricked out of their property. Assumption especially angered the South. Northern states owed a disproportionate share of the debts Hamilton proposed to take over, meaning they stood to gain a financial windfall at the expense of southern taxpayers. Besides, northern speculators had by now bought up so much of the outstanding southern state debt that they would pocket the real profits of assumption—again at southern expense.

In Congress, James Madison of Virginia rallied opponents of Hamilton’s proposals with two of his own: no assumption of state debts at all, and no funding of the national debt without making a distinction between the original and subsequent holders of government paper. The debate over Madison’s alternatives went on, inside Congress and out, for weeks. Toward the end of February, the House defeated his discrimination idea. Assumption failed a preliminary vote in mid-April. By early June, while more or less certain his funding scheme would get through, Hamilton was increasingly fearful that assumption wouldn’t survive a second and decisive ballot.

It was at this juncture, Jefferson later recalled, that Hamilton offered a compromise. The two men chanced to meet one day in the street, just outside the president’s house, Hamilton appearing “sombre, haggard, & dejected beyond despair, even his dress uncouth & neglected.” Hamilton begged Jefferson to reassure southern congressmen that assumption was vital to the well-being of the republic; in return, he would round up enough northern votes to move the national capital to a site on the Potomac River.

Anxious to get the government out of the clutches of New York “moneyed men,” Jefferson suggested that Hamilton and Madison join him for dinner the next evening at his house on Maiden Lane. There the bargain was sealed.2

At the Poughkeepsie convention, New York Federalists had more or less promised that the federal government would remain in New York if the Constitution were ratified. Now, shocked and embarrassed by this latest turn of events, they geared up for a fight to keep the federal government in the city as long as possible (or, failing that, to locate the federal district along, say, the Susquehanna, or even in Baltimore). Hamilton was adamant, however. His financial program, he told Senator Rufus King, was “the primary object; all subordinate points which oppose it must be sacrificed.” King and the others did as they were told. Early in July, Congress voted to build a permanent capital in a ten-mile-square federal district on the Potomac; for the remainder of the decade, pending completion of the necessary construction, the government would return to Philadelphia. In due course, both houses approved assumption as well as funding, completing Hamilton’s victory.

On August 12, 1790, Congress met for the last time in Federal Hall. Two weeks later, on August 30, Washington stepped into a barge moored at Macomb’s Wharf on the Hudson and left Manhattan, never to return. Abigail Adams vowed to make the best of Philadelphia but knew that “when all is done, it will not be Broadway.”

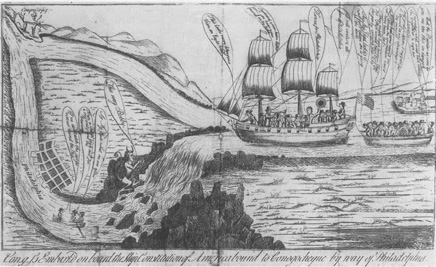

“Cong_ss Embark’d on board the Ship Constitution,” a New Yorker’s satirical view of the decision to move the federal capital to the Potomac. It is the Devil who lures the ship of state onto the rocks, but his words—“This way, Bobby”—echo the widespread belief that Robert Morris and other Pennsylvanians were behind the move. (Library of Congress)

New Yorkers watched the federal departure with both regret and irritation. “No more Levee days and nights, no more dancing parties out of town thro’ the summer, no more assemblies in town thro’ the winter,” lamented one resident. Everyone blamed the Pennsylvanians—to which Senator William Maclay, who had never liked New York anyway, testily replied that its residents “resemble bad school-boys who are unfortunate at play: they revenge themselves by telling notorious thumpers.” Even Washington came in for a share of abuse when he signed the Potomac bill into law. Hamilton, whose role in the deal wouldn’t come to light for years, emerged unscathed.

Yet by the end of the summer, the loss of the capital had been forgotten. Passage of the funding and assumption bills restored between forty and sixty million dollars in hitherto virtually worthless certificates of indebtedness to face value— a sudden accession of wealth that bathed the city (or at least its successful speculators) in prosperity. Even the state government had invested a couple of million dollars in securities that, redeemed at par, brought a tidy sum into the treasury. Eager investors were meanwhile bidding up the price of the new 6 percent and 3 percent federal securities, dreaming of fortunes to come.

To a visiting British diplomat, the city’s future seemed utterly secure, capital or no capital. New York, he said, “is certainly favored to be the first city in North America, and this superiority it will most assuredly retain whatever other spot be made the seat of government.”

It was an arresting thought: henceforth the United States would have two centers, one governmental, the other economic. This separation of powers, as emphatic as anything in the Constitution, had no parallel in the Western world. London, Paris, Amsterdam, Berlin, Vienna, Rome, Madrid, Lisbon—these were capitals in the fullest sense of the word, hubs of national politics, business, and culture (only the rivalry between Moscow and St. Petersburg even vaguely resembled the American case). That New York already promised to become the first city of the United States, independent of the apparatus of state power, was an augury of its uniqueness. Nowhere else in the republic would the marketplace come to reign with such authority, or painters and politicians alike bow so low before the gods of business and finance. No longer the capital city, its destiny was to be the city of capital.

Some New Yorkers wanted the city to become a center of industrial manufacturing too—filled with English-style factories, not just the small artisanal workshops with which it had long been well supplied. In January 1789, over “wine, cakes, etc.” at Rawson’s Tavern on Water Street, a committee of prominent businessmen formed the Society for the Encouragement of American Manufactures, commonly known as the New York Manufacturing Society. The promotion of industry was nothing new: the nonconsumption and nonimportation movements twenty-five years before had inspired similar projects, none of which met with much success. Yet the inception of a new federal government, President Washington’s words of encouragement for the country’s infant textile industry, and the strength of the city’s capital market suggested that large-scale manufacturing was an idea whose time had come. Even Governor Clinton, idol of the state’s rural republicans, had been heard to say that “the promotion of manufactures is at all times highly worthy of the attention of government.” No one was surprised when nearly two hundred investors bought up all Manufacturing Society stock at twenty-five dollars per share.

Before the year was out, the Manufacturing Society had opened a textile factory on Crown (later Liberty) Street. It had a carding machine and two hand-operated spinning jennies, and it employed fourteen weavers and 130 spinners, an impressive labor force by contemporary standards; it was also said to have cost $57,500—almost as much as the city had spent to renovate Federal Hall. A young Derbyshire immigrant named Samuel Slater offered to build and install, from memory, the spinning jennies whose design the British government guarded as carefully as the crown jewels. The factory’s managers turned him away, however, and within a year or two were forced to close their doors. Slater moved on to Pawtucket, Rhode Island, where he built the first successful cotton mill in the United States for the firm of Almy and Brown.

Advocates of manufacturing didn’t quit. The New York Society for the Promotion of Agriculture, Arts, and Manufactures, founded in 1791 by Robert R. Livingston and others, remained for years one of the country’s leading exponents of direct government support for American industrial development. Local organizations of manufacturers and workingmen likewise bombarded Congress with demands to protect infant industries from foreign, especially British, competition. Individual entrepreneurs, including many British immigrants and New Englanders, went on experimenting with cotton mills, iron foundries, pottery works, breweries, and thread mills. One visitor saw a cotton mill at Hell Gate on the East River in 1794.

The demise of the Manufacturing Society was nonetheless a signal that large-scale industrial manufacturing faced immense obstacles in New York. Manhattan lacked the water power necessary for mills and factories. City real estate was already very expensive, almost prohibitively so for high-risk ventures that might take years to show a profit. Inexperienced management, the lack of up-to-date technology, and competition from low-cost British imports compounded the problem. Besides, investors could almost always do better, with less danger, in shipping, insurance, and other mercantile enterprises, to say nothing of land or stock speculation. Over time, more and more of New York’s merchants and financiers came to think of manufacturing as a nuisance. It threatened to open competitive outlets for capital, they charged, while the protectionist trade policies advocated by its proponents posed a danger to the free movement of goods, money, and credit across national boundaries.

Fighting over the direction of the nation’s political and economic future resumed in Philadelphia in mid-December 1790 when Hamilton dispatched a second report on public credit to Congress. Among other things, the report recommended creation of a Bank of the United States. British experience proved, Hamilton said, that a bank was vital to national stability and prosperity. It would facilitate the financial operations of the treasury. Bank stock, a portion of which could be bought with the new public stock, would forge yet another link between public creditors and the federal government. Because its notes would serve as a circulating medium, and because its capital could be loaned out to private entrepreneurs, a national bank would further stimulate the nation’s trade and commerce. Jefferson and Madison protested that the Constitution gave the federal government no authority to charter such a bank, but the necessary legislation sailed through Congress and was signed into law by the president at the end of February 1791.

The new Bank of the United States got off to a shaky start. Against Hamilton’s wishes, the BUS board of directors decided to open a branch in New York, where the Bank of New York had just lost another attempt to get a charter from the state. The BONY’s capital resources were larger than ever, but the number of shareholders had dwindled to twenty-five or so, mostly wealthy merchants like Rufus King, Isaac Roosevelt, and Nicholas Low—exactly the men to whom the BUS branch could be expected to appeal for support. Was there room for two banks in New York? Would the potential danger to the BONY cause a local backlash against the new federal institution? Certainly Governor Clinton and his friends thought a state bank might offset the power of the BUS, and they decided to give the BONY a charter after all, reserving the right for the state to buy a hundred shares of stock for fifty thousand dollars.

None of this had been sorted out when, on July 4, 1791, BUS stock went on sale in Philadelphia at twenty-five dollars a share. Within two hours, frenzied buyers—led, as Madison and Jefferson had feared, by northern and European “moneyed men”—snapped up the entire offering. In no time at all, bank stock as well as federal loan certificates were on the auction blocks in New York as well, and as Madison reported to Jefferson, the Coffee House was in “an eternal buzz with the gamblers.” City newspapers began printing the latest quotations, and special express couriers rode in with current prices on the Boston and Philadelphia markets. “O that I had but cash” was the general cry, reported the New-York Journal, “how soon would I have a finger in the pie!”

The value of BUS “subscription shares” or “scrip” climbed steadily—from $25 to $45 to $60 almost overnight, from $60 to $100 in two days, from $100 to $150 in a single day. Toward the end of October shares in the bank were selling for $170. It was clear by this time that a number of Hamiltonians had acquired big stakes in the BUS as well as seats on its board; some indeed had seats on the BONY board as well, giving the two banks something close to interlocking directorates. (The state of New York hedged its bets by investing sixty thousand dollars in BUS stocks.) In the meantime, according to one of Andrew Craigie’s associates, ordinary mechanics and shopkeepers had begun to dream of making easy money in the market—a danger because “ideas of this kind being disseminated amongst the various Classes of people become subversive of private industry, happiness, & economy.”

Hamilton too worried about the “scriptomania” raging in New York, but his attention was momentarily diverted by another of his projects, the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures. The purpose of the SUM was to promote the industrialization of the United States, diversifying the country’s economy and reducing its dependence on imported, chiefly British, manufactures. SUM shares, valued at a hundred dollars each, could be purchased with either federal securities or BUS stock as well as specie—an ingenious arrangement that not only enabled the project to draw upon the increasing sums of foreign as well as domestic capital sluicing into the New York financial market but would also, in the process, help brake excessive speculation by stabilizing the demand for government bonds.

Although its operations would be located at Paterson, New Jersey, the SUM’s New York connection was repeatedly underscored—by the fact that a majority of its directors were big New York speculators, by the board’s decision to make William Duer its first governor or president, by the speed with which its stock was taken up by New York investors, and by its selection of L’Enfant to lay out a company town (his sense of grandeur proved too expensive, however, and he was let go). As of November 1791 over $625,000 had been raised toward an initial capitalization of one million dollars—the bulk of it from the city, where SUM stock was selling at or above par. A month later Hamilton gave Congress a Report on Manufactures that urged federal support for all such undertakings (because, among other things, idle “women and Children are rendered more useful” by employment in manufacturing).

At the end of December 1791, former assistant secretary of the treasury William Duer mobilized a small group of New York speculators—among them Alexander Macomb, John Pintard, William Livingston, and Royal Flint—for a daring attempt to manipulate the city’s stock market. The plan called for “the Company” or “the Six Per Cent Club,” as it was known, to make massive secret purchases of government paper and bank stocks (Duer himself had bought over half a million dollars’ worth in the previous nine months alone). To keep the market percolating, the club would also announce the formation of a new bank with an initial capitalization of a million dollars, then hint that this so-called Million Bank would merge with both the Bank of New York and the Bank of the United States. Stocks of all three institutions were certain to rise in value. When they had gone up far enough, the club would unload its holdings at tremendous profits—and perhaps (though Duer’s exact intentions remain hazy) seize control of the Bank of New York as well.

Shares in the Million Bank went on sale in January 1792. Excited investors bought the entire offering within a matter of hours, and the ensuing cry for bank stocks of every description threw the city into what startled participants referred to as a “bancomania.” By the end of the month, competing groups of speculators had entered the fray with two more banks having a combined capitalization of $1.2 million. As the financial market surged higher and higher, New Yorkers feverishly bought and sold stocks in all five banks. “The merchant, the lawyer, the physician and the mechanic, appear to be equally striving to accumulate large fortunes” through speculation, marveled one witness to the hysteria. Duer and company plunged deeper and deeper into debt to finance their purchases, Macomb even kicking in fifty thousand dollars from the SUM treasury—practically its entire cash surplus.

Early in March, while promoters of the three new banks maneuvered for money and legislative approval, stock prices leveled off, then declined. Coincidentally, the government notified Duer of a $250,000 discrepancy in his accounts as assistant treasury secretary. Cornered, and no longer able to raise cash, Duer began to sell. On March 10, as panic engulfed New York, he stopped payment on all his debts; two weeks later his creditors had him arrested and thrown in debtor’s prison. Macomb and Walter Livingston soon went to jail as well; John Pintard escaped his creditors by fleeing across the Hudson to Newark.

New York appeared to have been struck by a disaster of staggering proportions. Duer alone owed more than $750,000. Judge Thomas Jones said that estimates of all losses ran as high as three million dollars—a huge sum, representing the savings of “almost every person in the city, from the richest merchants to even the poorest women and the little shopkeepers.”

“Everything is afloat and confidence is destroyed,” one man grieved. “The town here has rec’d a shock which it will not get over in many years.” No one escaped—“shopkeepers, widows, orphans, butchers, carmen, Gardeners, market women & even the noted bawd, Mrs. McCarty,” lost their life savings. “Such a revolution of property perhaps never before happened.” All told, two dozen leading merchants were ruined; the Million Bank and its competitors never opened their doors. Business languished, and ships lay at the wharves with no one to buy their cargoes. Artisans, mechanics, and cartmen couldn’t find employment. Farmers couldn’t sell their produce. Over in Paterson, the directors of the SUM (absent Duer and Macomb) forged ahead with plans for the construction of factories and housing for workers, but the wounds were fatal, and within a few years the project foundered.

Hamilton, watching the nation’s first financial crisis unfold, was appalled. The whole point of his financial program was to transform the nation’s public creditors into a class of proto-capitalists able to lend the government stability and facilitate the production of tangible wealth—not reel off on speculative binges that paralyzed the economy. “There should be a line of separation between honest men and knaves,” he fumed, “between respectable stockholders and mere unprincipled gamblers.” In March and again in April he ordered the treasury into the market in an effort to restore confidence and give “a new face to things.” It helped, but not much. Where, and how, to draw the line between “respectable stockholders” and “gamblers” would remain a central dilemma of American capitalism for the next two centuries. The demise of the SUM had meanwhile soured Hamilton’s interest in such projects, and when Congress refused to act on his Report on Manufactures, he quickly lost interest in the subject.

Duer was lucky to be behind bars. Everyone blamed him for the panic, and threats against his life were commonplace. “I expect to hear daily that they have broken open the jail and taken out Duer and Walter Livingston, and hanged them,” wrote one resident. On the night of April 18 a stone-throwing crowd of between three and five hundred persons, working people as well as merchants, converged on the jail shouting, “We will have Mr. Duer, he has gotten our money. “Nothing much happened, but the scene was repeated for the next several evenings and the mayor prudently increased the guard at the jail. Duer appealed to his old ally Hamilton for assistance. Hamilton advised him, stiffly, to make a clean breast of his affairs and settle with his creditors. “Adieu, my unfortunate friend,” wrote Hamilton. “Be honorable, calm, and firm.”

Like Hamilton, New York’s “moneyed men” came out of the Panic of 1792 eager to draw the line between honest investment and knavish speculation. When trading in public stocks began two or three years earlier, the market was dominated by auctioneers who knocked down consignments of government paper to the highest bidder like any other commodity (and often, indeed, side by side with other commodities). Two of the most active, Leonard Bleecker and John Pintard, formed a partnership in July 1791 and held auctions in the Long Room of the Merchants’ Coffee House, three times a week at one P.M. and three times a week at seven P.M. Although these events were open to the general public, the great majority of stock purchases appear to have been made either by wealthy “dealers,” also known as “jobbers,” who bought and sold on their own accounts (often, like Duer, using borrowed money), or by “brokers,” who acted on behalf of specific customers. Between auctions, dealers and brokers would meet outside to trade stock among themselves. During the summer of 1791 they gathered under a buttonwood (sycamore) tree on Wall Street.

That September, as the volume of sales increased and bank stocks joined public stocks on the market, the city’s auctioneers, dealers, and brokers drew up the first set of rules governing the sale of securities. Five months later, in February 1792, the auctioneers opened a Stock Exchange Office in “a large convenient room for the accommodation of the dealers in stock” at 22 Wall Street. Then, in March, Duer failed and the market collapsed.

In the ensuing panic, the auction system came under heavy criticism for having been too easily manipulated by unscrupulous auctioneers and dealers who rigged prices and circulated false rumors. At the end of March, hoping to restore confidence in the market, a number of dealers and brokers met at Corre’s Hotel and signed a promise to boycott future auctions and find “a proper room” in which to do business; several weeks later, the legislature flatly outlawed the auctioning of federal or state securities.

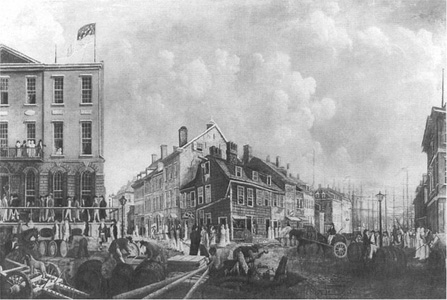

On May 17, 1792, twenty-four brokers and dealers drew up the so-called Buttonwood Agreement, which laid the foundations for a structured securities market without the now discredited auctions. The signers agreed to a fixed minimum commission rate, and they promised “that we will give a preference to each other in our Negotiations.” Early in 1793 the brokers and dealers moved into an upstairs room of the elegant new Tontine Coffee House, situated on the northwest corner of Wall and Water streets. Wags dubbed it “Scrip Castle.” (The Wall Street “curb market” didn’t disappear, however: in warm weather, stock traders continued for many years to assemble on the pavement outside.)

The Tontine Coffee House, by Francis Guy, c. 1820. The Coffee House was the large building on the left, occupying the northwest corner of Wall and Water streets. Note the merchants and traders gathered on its balcony, as well as the presence of women in the street below—a reminder that private residences were still common in this part of town. (© Collection of The New-York Historical Society)

Construction of the Tontine Coffee House symbolized the fear of disorderly capital markets that became a recurring feature of the city’s economic life. It was also an early indication that the Panic of 1792 wouldn’t, as some had feared, cause prolonged harm to the city’s economy. By the following June a local paper could declare that rumors of New York’s problems “have been very exaggerated and falsified. . . . Credit is again revived—and prosperity once more approaches in sight. . . . Trade of every kind begins to be carried on with spirit and success.” Events unfolding in France would accelerate the recovery and thrust New York further ahead of its rivals than anyone could have imagined.