The summer and fall of 1789 found New York agog with the news of revolution in France. Parisian rioters sack the Bastille! The National Assembly issues a Declaration of Rights! The nobility surrenders feudal privileges! For many residents, this was the death knell of despotism and the dawn of the republican millennium. Manhattan crowds hailed “the Friends of revolution throughout the world,” and French liberty caps enjoyed a sudden vogue. The new Uranian Society, founded by thirty recent Columbia graduates to debate current events, resolved that the French Revolution was a blessing to mankind. Even Alexander Hamilton was caught up in the excitement. “As a friend to mankind and to liberty I rejoice in the efforts which you are making,” he confided to Lafayette.

By the autumn of 1792 the situation had grown more complicated. Prussian and Austrian forces had invaded France; fighting had broken out in the streets of Paris; Louis XVI had been arrested; a new National Convention had abolished the monarchy and proclaimed France a republic. The winter of 1792-93 brought still more astonishing intelligence: the Prussians and Austrians had been repulsed; Louis had been guillotined for treason; France had declared war on Great Britain, Spain, and Holland. In the summer of 1793 word came that Maximilian Robespierre’s radical Jacobins were preparing a campaign of terror against all enemies of the Revolution.

These distant events were made startlingly immediate by the arrival in New York of a stream of political refugees or émigrés—Bourbon absolutists, constitutional monarchists, and republicans, among them such literary and political luminaries as Charles Maurice de Talleyrand, the due de La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, Victor-Marie du Pont de Nemours, Chateaubriand, Volney, and Prince Louis Philippe, the future monarch. “The City is so full of French,” observed the English traveler William Strickland in 1794, “that they appear to constitute a considerable part of the population.” A French and American Gazette was founded in 1795 as a bilingual paper; the following year it became the purely French Gazette Française.

The ferment of revolution was at work nearer home too, in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti). Inspired by appeals for liberty, equality, and fraternity and by the April 1792 decree abolishing slavery, Saint-Domingue’s 450,000 blacks rose against their masters. Troops sent from France to restore order were routed by insurgents under the command of Toussaint Louverture. By the end of 1793, 90 percent of the colony’s forty thousand whites, royalists as well as republicans, had fled to the United States. All told, four or five thousand people, creole planters and black servants alike, debarked in New York City.

Like the French, the exotic Domingans were a conspicuous addition to the population. John F. Watson, an early nineteenth-century antiquarian, remembered well how their appearance caused frissons of excitement among townsfolk who thought they had seen everything: “Mestizo ladies, with complexions of the palest marble, jet black hair, and eyes of the gazelle, with persons of exquisite symmetry, were to be seen escorted along the pavements by white French gentlemen, both dressed in the richest materials of West India cut and fashion; also coal black negresses in flowing white dresses, and turbans of ‘muchoir do madras,’ exhibiting their ivory dominos, in social walk with white, or mixed Creoles.” Altogether, Watson recalled, they formed “a lively contrast with our native Americans, and the emigres from old France, most of whom still kept to the stately old Bourbon style of dress and manner; wearing the head full powdered a la Louis, golden headed cane, silver-set buckles, and cocked hat.”

Maintaining such appearances wasn’t easy, even for the most eminent émigrés. Many found work as dancing masters, fencing masters, milliners, musicians, gunsmiths, jewelers, weavers, furniture makers, watchmakers, booksellers, printers, and the like. Antheleme Brillat-Savarin, the future gastronome, played in theater orchestras, taught French, and, at Little’s Tavern, gave the proprietor instruction in how to prepare partridges en papillate and other delicacies. Other émigrés earned their livelihoods as laborers, dockworkers, hod carriers, or draymen. The widow and children of John Berard du Pithon, once a wealthy Domingan planter, were supported by their slave, Pierre Toussaint, a successful hairdresser—so successful that he eventually became the city’s most celebrated coiffeur and a trusted confidant of powerful society matrons.

President Washington’s cabinet was sharply divided on the issue of how the United States should act toward the belligerents in Europe. Jefferson favored recognition of the French republic, strict compliance with the 1778 Franco-American treaty, and prompt accreditation of the new French ambassador, Edmond Genêt. Hamilton, now concerned that the revolution in France had gone too far, advised withholding diplomatic recognition, suspending the treaty, and ignoring Genêt. A second war with Great Britain, he argued, would ruin his program for national growth and development. President Washington tried to steer a middle course. At the end of April 1793 he issued a Neutrality Proclamation, declaring that while the United States government would abide by the treaty and receive Genêt, it wouldn’t take sides in the conflict. American citizens were advised to act in a “friendly and impartial” manner toward all the warring powers. Three months later Jefferson submitted his resignation.

New York’s merchants applauded neutrality. The city had only just rebounded from the 1792 panic, and the local economy remained dependent on Great Britain. Not only did virtually all foreign manufactured goods come from the British Isles, but many New York importers continued to function on British capital and credit as well. Furthermore, although the export business was gradually diversifying as city traders sought new markets in China and elsewhere, there was still hope on the docks of fully restoring trade with the British West Indies. If war with France, a sister republic, was almost unthinkable, war with Great Britain might well sink the city’s economy.

European war might nevertheless do wonders for business—assuming the United States could remain neutral and trade with all the warring parties. As early as May 1793 the highly regarded mercantile firm Lynch and Stoughton noted that demand on the Continent for American produce was growing fast and should realize handsome profits. The future looked even better after France opened its West Indian colonies to American commerce. Staple exports to the Caribbean soared during the summer of 1793, along with the earnings of more than a few city merchants.

But neither Britain nor France accepted American neutrality for long. Britain said it sustained French colonial trade; France claimed that it reneged on the 1778 alliance and perforce aided the British. Each proceeded by turns to punish the United States for its impartiality, and for the better part of the next decade, New Yorkers contended with a succession of diplomatic crises, international incidents, and threats of war.

First to strike were the British. In the summer of 1793 His Majesty’s government began a massive deployment of naval power to enforce a blockade of France and French colonial possessions. Neutral commerce with the French West Indies was banned under the so-called Rule of 1756, according to which trade with enemy colonies prohibited in time of peace couldn’t be legalized in time of war. This was a direct blow at the United States, whose vessels dominated the carrying trade throughout the Caribbean. Hundreds of American ships, dozens of them from New York, were seized and confiscated by the British over the winter and spring of 1793-94. Numerous American seamen, among them many New Yorkers, were impressed into the Royal Navy or imprisoned in West Indian jails. Lurid stories circulated that the British, who continued to occupy five forts on New York territory in violation of the 1783 peace treaty, were urging the Iroquois to attack frontier settlements.

It was an uprising by some home-grown Manhattan “Indians,” however, that almost put an end to Washington’s neutrality policy.

On October 12, 1792, several hundred New Yorkers in war paint, bucktails, and feathers had gathered solemnly around a fourteen-foot obelisk dedicated to the memory of Christopher Columbus. “Transparent devices” on each face of the obelisk depicted key events in the career of that “nautical hero and astonishing navigator”—Columbus receiving a compass from Science, Columbus wading ashore in America, Columbus at the end of his life, neglected by all but the “Genius of Liberty.” Many of those present would have recalled the figure of Columbus that led the Grand Federal Procession of 1788, but this ceremony— marking the three hundredth anniversary of his initial landfall—was the new nation’s first proper Columbus Day celebration. It was also one of the first public events staged by a new organization in town, the St. Tammany Society, or Columbian Order.

Twenty years earlier, back in the tumultuous 1770s, Philadelphia patriots had celebrated a St. Tammany Day in honor of the mythical chief Tamamend, whom the Delawares credited with carving out Niagara Falls and other heroic feats. After Independence, Tammany Societies arose in many parts of the country as vehicles for the expression of popular patriotism and republicanism; often they represented hostility to the Society of the Cincinnati, an elitist organization of former Continental Army officers. A Tammany Society had appeared in New York in 1786 or 1787 but languished until 1789, when the merchant John Pintard and a onetime Tory upholsterer named William Mooney took it over, charging it with a new sense of purpose.

One of his principal goals, Pintard told Thomas Jefferson, was to “collect and preserve whatever relates to our country in art or nature, as well as every material which may serve to perpetuate the Memorial of national events and history.” Two years later, in 1791, the society’s American Museum opened in an upper room of City Hall; when those quarters proved inadequate, the museum moved to the Merchants’ Exchange on Broad Street. Contrary to Pintard’s expectations, though, its holdings consisted mostly of stuffed animals and doleful curiosities like the “perfect Horn, between 5 and 6 inches in length, which grew out of a woman’s head in this city.” In 1795 the society washed its hands of the whole thing.

More fruitful was Pintard’s wish to put the society on a “strong republican basis” and to endow it with “democratic principles” that would help check the resurgence of New York’s “aristocracy” (a curious ambition given Pintard’s association with William “King of the Alley” Duer). Any citizen able to pay a small initiation fee and modest dues could join, and by the mid-nineties some five hundred residents of the city had done so. Some Tammany members were youthful lawyers and merchants, but most were “artisans” or “mechanics” (masters and journeymen in the skilled trades, as distinct from apprentices, cartmen, sailors, and laborers).

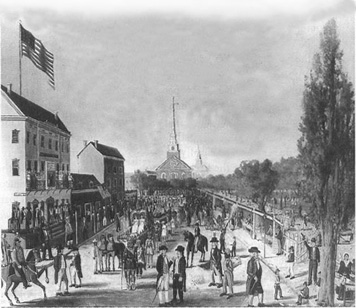

At first Tammany stuck to displaying its republican zeal via comic-opera appropriations of Native American nomenclature and ritual. Rank-and-file members, called “braves,” were assigned to “tribes.” They elected a board of directors or “sachems,” who in turn picked the society’s “grand sachem” (a position Mooney held for many years), and once a month they all congregated in their headquarters or “Wigwam” for an evening of eating, drinking, singing, storytelling, and debates on issues of current interest. The braves’ choicest moments were a handful of holidays—Washington’s Birthday, Independence Day, Columbus Day, Evacuation Day, and the society’s own Anniversary Day (May 12)—when they paraded through town in full Indian regalia, cheered patriotic orations, then sat down for mammoth open-air banquets along the East River. By the mid-1790s their Anniversary Day spree was widely considered the premier public event in the city.

Under the spur of revolutionary events abroad, however, Tammany became increasingly involved in local politics. New York’s laboring population was showing signs of restlessness with Hamilton and the Federalists. The General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen, irate because it had failed to pry a charter of incorporation out of the legislature, had run its own ticket in the 1791 elections, four of its nominees capturing seats in the Assembly. Artisans grew even more disaffected—and drew closer to the rival Clintonians—during the national furor over the Federalist financial program. Though Hamilton’s handiwork remained more popular in New York than elsewhere in the country, its less savory consequences—rampant speculation in public stocks, followed by the unnerving Panic of 1792—raised troubling questions about privilege, greed, corruption, and other antirepublican tendencies in Washington’s administration. The General Society, increasingly vocal on this point, warned city residents against an “overgrown monied importance” and “the baneful growth of aristocratic weeds among us.” Philip Freneau, poet-editor of the antiadministration Daily Advertiser, complained in verse that “some have grown prodigious fat / And some prodigious lean!”

The Tammany Society celebrating the Fourth of July, 1812, by William Chappel. Line of march up Park Row, with the Brick Presbyterian church in the rear and Tammany headquarters on the left. This was one of the last occasions on which the braves and sachems appeared in their original Indian costumes. (© Collection of The New-York Historical Society)

Governor George Clinton, joined by the disaffected Livingston clan, had meanwhile opened lines of communication with Madison and Jefferson. The two Virginians came up for a tour of the state in 1791, saying they intended only to “botanize.” Yet there was enough political talk thrown in along the way to justify the later belief that their trip founded the Virginia-New York axis of a new national opposition party.

The 1792 gubernatorial elections confirmed that the Federalist chokehold on New York was weakening. Clinton survived a tough contest with John Jay to capture his sixth three-year term, drawing 603 votes in the city to Jay’s 739—a substantial broadening of support for the governor, who had received only a hundred or so votes in the city as an Antifederalist candidate for the Poughkeepsie convention.

The spirit of opposition ripened during 1793 as the tempo of the French Revolution quickened. Mechanics, laborers, and some smaller merchants began to believe that international republicanism was in mortal danger—here from the machinations of Tory-loving “moneyed-men” like Hamilton and Duer, there from the armies of reactionary despots, and on both sides of the Atlantic from the malevolent influence of British agents, British arms, and British gold. Did not American neutrality at such a moment smack of political heresy and betrayal?

New York Federalists, on the other hand, shocked by the execution of Louis XVI and the rise of the radical Jacobins, concluded that the revolution had gone off the rails. The upheaval in France was being “conducted with so much barbarity & ignorance,” said Rufus King, that sensible people could no longer countenance it. American neutrality was more imperative than ever, Federalists argued, and the Chamber of Commerce, a Federalist stronghold garrisoned by the city’s principal merchants, reiterated that American involvement in the war would mean economic disaster.

While remaining officially nonpartisan, the Tammany Society began to mobilize popular support for the French Republic. Tammany braves and their friends greeted every scrap of good news from France with noisy parades and raucous banquets. After its Anniversary Day festivities in May 1793, four hundred participants trained through the streets in red liberty caps. When the French warship L’Embuscade (Ambush) docked in New York in June, Tammany men led a tumultuous throng down to Peck Slip, where they showered the arriving officers and crew with tricolor cockades and chorus after chorus of “La Marseillaise,” the Revolutionary anthem. In July, Tammany turned the “Glorious Fourth” into a celebration of international revolution, a day-long carnival of parades, fireworks, bell ringing, singing, guzzling, stuffing, sermonizing, and speechifying.

Later that same month, a British frigate, the Boston, hove into port. Her crew fell to brawling with the crew of L’Embuscade and the pro-French regulars of waterfront grogshops. At one point, a large party of French sailors and sympathetic residents marched down to Bowling Green, where they dug up and demolished fragments of the statue of George III torn down some seventeen years earlier. The captain of the Boston then challenged his French counterpart to a naval duel. On August 1 both ships dropped down to positions off Sandy Hook, trailed by nine boatloads of excited spectators from the city. To their immense satisfaction, L’Embuscade claimed the victory after a fierce two-hour exchange of cannon fire and was escorted back to Manhattan by the French fleet, fifteen ships of the line that miraculously sailed into view just as the smoke was clearing. Thousands of cheering residents converged on the Battery to greet the French. Women collected old linen to make bandages for injured French sailors, and in an emotional ceremony, L’Embuscade’s colors were presented to the Tammany Society as a token of republican fraternalism.

Republican fraternalism had its limits, though. Only days later, Edmond Genet, the French ambassador, arrived on the scene, cockily predicting that New York would give him a hero’s welcome. “The whole city will fall before me!” he crowed. The problem was that “Citizen” Genet had repeatedly thumbed his nose at Washington’s Proclamation of Neutrality by commissioning American privateers to prey on British and Spanish commerce in the West Indies. This undiplomatic behavior caused a furor around the country, and the cabinet had just voted to ask the French government to bring him home; even Secretary of State Jefferson admitted that Genet had become a political liability. His reception in the city was thus chillier than he had bargained on. White Mat-lack of the General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen escorted him to a banquet at the Tontine Coffee House, and over the next few months he dined with various opposition leaders—mostly, it was said, because he had tens of thousands of dollars to spend on refitting the French fleet. (Recalled by the Jacobin regime in early 1794, Genêt applied for asylum, took an oath of allegiance to the United States, and retired to a farm near Jamaica on Long Island. He later married Governor Clinton’s daughter, Cornelia, and settled down to dabble unsuccessfully in business and tinker with steam-propelled balloons and other mechanical gadgets.)

The French warship L’Embuscade off the Battery in 1798, drawn by John Drayton. Washington Irving said the flagstaff on the right looked like a giant butter chum, and the “churn” was a local landmark for years. (I. N. Phelps Stokes Collection. Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

Genêt notwithstanding, the French Revolution still commanded a broad following in New York. In mid-January 1794 boisterous celebrations erupted again over reports (subsequently proved false) that the French had captured the Duke of York. The “lower class of citizens,” Peter Livingston noted with satisfaction, still loved the French so much that they were “almost to a Man . . . Frenchmen.”

Consistent with Livingston’s judgment was the success of a new organization, the Democratic Society. One of forty similarly named groups around the United States—at least some of which seem to have been founded with Genet’s assistance—the New York Democratic Society made its debut in early February 1794, vowing “to support and perpetuate the EQUAL RIGHTS OF MAN.” Its leaders were a cross-section of “old Whigs” and Clintonian “new men” like Commodore James Nicholson (the president), David Gelston, Henry Rutgers, Melancton Smith, and two young lawyers of whom much would be heard in the very near future, Tunis Wortman and William Keteltas. Rank-and-file members, somewhere between one and two hundred strong, included master craftsmen, apprentices, and laborers, among them many recent Scottish and Irish immigrants (Donald Fraser, president of the Caledonian Society, was another of the Democratic Society’s founders).

Resolutely pro-French, the Democratic Society clamored for war with Britain. Throughout the spring and summer of 1794 New York churned with rallies, demonstrations, and marches. When French forces recaptured Toulon, the Democratic Society organized eight hundred working people to parade through town in liberty caps, arm-in-arm with French officers, as thousands of cheering onlookers lined the sidewalks. At Corre’s Tavern the celebrants downed toasts to the armies and fleets of France (nine cheers) and to the destruction of Britain’s “venal and corrupt” government (nine cheers). That evening, republicans and Frenchmen gathered at the Tontine Coffee House to sing the “Marseillaise” and dance the carmagnole. The Tammany Museum exhibited a guillotine, complete “with a wax figure perfectly representing a man beheaded!”

New York’s Federalists were horrified, all the more so when residents of the city, anticipating a British attack, decided to build fortifications on Governors Island. Every morning for nearly a month, drums beating and banners flying, shipwrights, cordwainers, journeymen, tallow chandlers, sailmakers, and Columbia College students trooped down to the Battery, where boats waited to carry them over to the island. “To-day,” wrote an amazed English visitor, “the whole trade of carpenters and joiners; yesterday, the body of masons; before this, the grocers, school-masters, coopers, and barbers.” Never, however, was the demise of the merchant-mechanic alliance more apparent than at the city polling places, where a fledgling “Democratic-Republican party”—a confederation of Clintonians, Livingstons, and popular societies—whittled down big Federalist majorities with organization, discipline, and conscious appeals to the interests and sentiments of workingmen.

New York’s Democratic-Republicans didn’t invent their electioneering practices out of whole cloth. The genealogy of such tactics reached back through the ratification struggle of 1787-88 to the pre-Revolutionary committees, perhaps as far back as the Morrisite “party of the people” in the 1730s or even the Leislerian movement in the 1690s. Nor had political parties or “factions” suddenly acquired legitimacy: their presence continued to be widely regarded as prima facie evidence of corruption and conspiracy. But in the furious press of events, actions ran far ahead of ideas. Federalist foreign and domestic policies had united disparate opposition forces and prompted them to seek power, in concert, by means not yet considered entirely right or proper. Unlike any of their predecessors, moreover, the Democratic-Republicans of New York had already begun to establish close working relations with similar parties emerging in Virginia, Pennsylvania, and elsewhere around the country—not yet a national party in the modern sense, but close.

In the spring 1794 legislative elections, thanks in great part to exertions by the Democratic Society, the Democratic-Republican ticket ran extremely well among small masters, tradesmen, mechanics, and apprentices, especially in the city’s poorer wards. It wasn’t enough to win, but it set the stage for the December congressional elections, in which Edward “Beau Ned” Livingston challenged the Federalist incumbent John Watts for the privilege of representing New York City. This was a race, said one excited Democratic-Republican, between “friends and enemies to the French or the swinish multitude and the better sort” (on the theory that Beau Ned, despite his wealth and connections, was really a man of the people).

Livingston defeated Watts by a margin of eighteen hundred to sixteen hundred—an upset that not only gave local Democratic-Republicans a voice in Congress but demonstrated the party’s increasing strength among the city’s middling and lower classes. Beau Ned did exceptionally well, it was noted, in the uptown wards that were home to the same working people who had so recently trooped out to work on the Governors Island fortifications. Once again, it was the Democratic Society that got them to the polls.

In an effort to avoid another conflict with the former mother country, President Washington dispatched Chief Justice John Jay to Britain to negotiate. It wasn’t a popular mission in Jay’s hometown. When he left for England in May 1794, only a couple of hundred well-wishers came to see him off. The militia, many of whose members belonged to the Democratic society, flatly refused to parade. As Jay’s ship weighed anchor, Governor Clinton, Chancellor Livingston, and the French consul stood together on the deck of a nearby French man-of-war, loudly singing French revolutionary anthems.

Democratic-Republicans worried because Jay, like other New York Federalists of his class, was an acknowledged Anglophile. Indeed, when Jay arrived in England and found his counterparts in a conciliatory mood, he quickly came to terms. By November 1794 Britain had agreed to evacuate the frontier forts, open British ports in the West Indies to American vessels, and submit disputed pre-Revolutionary debts to joint commissions.

But the United States paid a stiff price for these concessions. Jay tacitly abandoned the principle of freedom of the seas. He consented to give Britain most-favored-nation status in its trade with the United States. He promised that foreign (i.e., French) privateers would not be allowed to operate out of United States ports. He accepted a commercial accord in which American ships not exceeding seventy tons burden would be allowed to enter the British West Indies—providing the United States renounced the international carrying trade in cotton, sugar, and molasses. On the impressment of American seamen and compensation for slaves carried off during the war—two issues that had poisoned Anglo-American relations for years—Jay’s treaty said nothing.

In the uproar that followed, Jay and his party were very nearly destroyed. While still in England, and before his treaty’s terms were made known, Jay had been elected governor after George Clinton declined to stand for a seventh term. Soon after Jay returned at the end of May 1795, the U.S. Senate, after weeks of intense secret debate, narrowly ratified the treaty, except for the article limiting American trade with the West Indies. By July 1, when Jay was sworn in as governor, critics had begun a furious campaign in New York and elsewhere to dissuade President Washington from signing the pact. This opposition was bolstered by a new British crackdown on neutral vessels carrying provisions to France. Twenty-seven ships owned by New Yorkers were seized in the course of the summer, more even than in the 1793-94 crisis.

It was in this context that, in mid-July 1795, New York’s Democratic-Republicans scheduled a Saturday noon “Town Meeting” to express their “detestation” of the Jay Treaty. “Our demagogues always fix their meetings at the hour of twelve,” scowled one Federalist, “in order to take in all the Mechanics & Labourers—over whom they alone have influence and who in public meetings have a great advantage as they are not afraid of a black eye or broken head.”

It was by all reports the greatest such assemblage in twenty years and reminded everyone of the tumultuous popular rallies of the 1770s—except, that is, for the French tricolor flying alongside the American flag on the balcony of City Hall and the presence of numerous radical emigres and political fugitives from Ireland and Scotland, overwhelmingly sympathetic to the Democratic-Republicans. Grant Thorburn, an immigrant Scottish artisan whose earlier radical sympathies had by this time cooled, recalled what to him were the most frightening and disreputable elements of the crowd: “The Irish (patriot) laborer, his face powdered with lime, shirt sleeves torn or rolled up to his shoulders, came rattling up with his iron shod brogues; and the clam-men were there; and the boat-men were there; and the oyster-men were there; and the ash-men were there; and the cart-men were there.”

Alexander Hamilton was there too, surrounded by a small contingent of Federalists, who “looked on the multitude like affectionate parents beholding with sorrow the frantic tricks of their erring children.” Hamilton began to speak, Thorburn said, and although “his clear, full voice sounded like music over the heads of the rabble,” he was shouted down and pelted with stones. A large body of demonstrators, led by Peter R. Livingston, newly elected grand sachem of the Tammany Society, then marched off to Bowling Green, where they burned a copy of the treaty.

Later that day a group of Revolutionary War veterans paraded with French and American flags and burned a picture of Jay “holding a balance containing American independence and British gold, the latter predominating.” Hamilton, still full of fight, quarreled on the street with Commodore James Nicholson, head of the Democratic Society and honorary captain of the Federal Ship Hamilton in 1788. Nicholson accused his former ally of being “an abetter of Tories” and used “other harsh expressions.” Hamilton promptly challenged Nicholson to a duel, and Nicholson accepted. Moments later Hamilton had a second confrontation with prominent opponents of the treaty, shouting that he would “fight the whole party one by one . . . the whole detestable faction.” The former secretary of the treasury had become a mere “street Bully,” sneered Beau Ned Livingston.

The following Monday saw another and bigger crowd, perhaps as many as seven thousand people, return to City Hall and adopt a package of resolutions denouncing the Jay Treaty. As for Hamilton and Nicholson, their seconds worked out a face-saving settlement. Hamilton had nonetheless become so worried about the safety of his friends and himself in New York that he asked the federal government to station troops on Governors Island—a striking reversal of fortune for the man who eight years earlier had been the hero of New York’s working people.

Washington assented to the treaty in August, but despite his tremendous prestige, it continued to create controversy. In the city’s volatile, superheated atmosphere it became more and more difficult for organizations like the Tammany Society to maintain even an official political neutrality. Over the winter of 1794—95 Tammany Federalists pressed the membership to endorse President Washington’s criticism of “self-created” societies in the United States—above all the Democratic Societies, which Washington held responsible for the recent Whiskey Insurrection in Pennsylvania. When Tammany Democratic-Republicans, many of whom belonged to the New York Democratic Society, refused, the Federalists pulled out en masse. By spring Tammany allied itself openly with the new Democratic-Republican party, which now began to use “Tammanial Hall”—the Long Room of Abraham (Bram) Martling’s Tavern on Chatham Street (now Park Row)—as a kind of campaign headquarters on election day.

“Gallomania” also gripped the Democratic-Republican wing of fashionable society. Ladies and gentlemen with advanced principles as well as advanced means acquired a taste for French expressions, French food, French waltzes, French opera, French books, and French mattresses. Fancy boardinghouses became pensions françaises; upscale taverns became “restaurants” and began serving dinner at three in the afternoon, in the French manner, instead of noon. Well-to-do Democratic-Republican wives adopted low-cut gowns and gauzed coifs a lafranfaise, spurning the buckram and brocades still favored by Federalist matrons. Similarly, their husbands rejected powdered wigs, knee britches, and shoe buckles as insignia of the ancien regime. Instead, they wore their hair in the radical “Brutus Crop”—brushed forward from the crown—and affected the bloused shirts, linen cravats, and baggy pantaloons that were the uniform of continental revolutionaries.

But this was 1795 not 1775; New York, not Paris. Despite the liberty caps, choruses of “La Marseillaise,” and take-no-prisoners rhetoric, neither the Democratic-Republican party nor the popular societies allied with it were in a revolutionary frame of mind. They were rising enterprisers, successful craftsmen, aspiring journeymen, and respectable mechanics, not a mass of propertyless proletarian levelers. They demanded equality of opportunity and participation, not equality of condition. Their class-consciousness (if that is the word for it) admitted distinctions only between the productive and nonproductive classes of society—between those who came by their money through hard and honest labor, and those, like parasitic bankers, speculators, stockjobbers, and idle landlords, who relied on privilege and politics, money and monopoly to gain their position.

For all its limits, on the other hand, this artisanal republicanism was infused with egalitarian, democratic aspirations scarcely imagined a decade or two earlier. Over the next decade, indeed, it would bring about fundamental changes in the political system of the city.

One day in mid-November 1795 Gabriel Furman, a well-to-do merchant and prominent alderman, set out to return from Brooklyn to Manhattan via the ferry that docked at the foot of Fulton Street. Furman ordered the ferrymen, Thomas Burk and Timothy Crady, both recent arrivals from Ireland, to leave ahead of schedule. They refused. An argument ensued, Furman yelling that he would have “the rascals” thrown in jail, Crady yelling back that he and Burk “were as good as any buggers” and would use their boat hooks on anyone who tried to arrest them. As soon as the ferry got across to Manhattan, Furman summoned a constable and had the two marched off to the Bridewell while he thrashed them with his cane.

After twelve days behind bars, Burk and Crady came up for trial before the Court of General Sessions on charges of insulting an alderman and threatening the life of the constable. Neither man was allowed legal counsel; there was no jury; Furman was the only witness; and the presiding judge, Mayor Richard Varick, was clearly out to make an example of them. “We’ll learn you to insult men in office!” he shouted. The court found Burk and Crady guilty on both counts and sentenced them to two months at hard labor. For extra measure, Crady also received twenty-five lashes on his bare back.

The case took a new turn some weeks later when Burk and Crady broke out of jail and escaped to Pennsylvania. Writing as “One of the People,” lawyer William Keteltas (a youthful newcomer from Poughkeepsie) wrote an account of their ordeals for Thomas Greenleaf Journal. Keteltas denounced the court for its “tyranny and partiality.” Burk and Crady had been punished, he said, merely to “gratify the pride, the ambition and insolence of men in office.” The accusation stung, coming at a time when the mayor and aldermen were under fire for turning nine prisoners from the Bridewell over to a British man-of-war as alleged deserters.

The case of the long-gone Irish ferrymen suddenly blossomed into a republican cause célèbre in which upper-class arrogance menaced the dignity of ordinary citizens. “Do we live in a city,” asked one angry newspaper writer, “where the Mayor or an Alderman or two have a right to strip us naked and give us as many lashes as they please at a whipping post for what they may deem an insult to a magistrate?” Keteltas stoked the fires by petitioning the Assembly to impeach Varick and the magistrates for their “illegal and unconstitutional” conduct. In January 1796 the Assembly rejected the petition. Keteltas wrote another article for the Journal berating the Assembly for “the most flagrant abuse of [the people’s] rights” since independence. The Assembly in turn censured Keteltas for his “unfounded and slanderous” remarks. Keteltas repeated his attack on the Assembly.

Early in March, in an uncanny reenactment of Alexander McDougall’s experience twenty-five years before, the Assembly summoned Keteltas to explain himself. He showed up with two thousand supporters, admitted authorship of the offending newspaper articles, and refused to apologize (amid loud “clappings and shoutings”). When the Assembly then sentenced him to jail for “a breach of the privileges” of the house, the crowd hoisted him into a “handsome arm chair” and carried him off to the Bridewell, chanting, “THE SPIRIT OF SEVENTY-SIX! THE SPIRIT OF SEVENTY-SIX” After Keteltas got out a month later on a writ of habeas corpus, another crowd pulled him through the streets in a phaeton decked out with French and American flags, a liberty cap, and a large picture of a man being whipped, above which was the inscription “What, you rascal, insult your superiors?”

The Keteltas affair helped siphon away more of the Federalists’ popular constituency. A record four thousand residents of the city went to the polls in the spring 1796 legislative elections, and while the Democratic-Republicans failed to capture any of New York’s twelve Assembly seats, they pulled five hundred votes more than the year before. More important, two-thirds of the Democratic-Republican voters were men of little or no property, many of them the immigrants whose numbers had grown markedly in recent years. Six months later, in the September Common Council elections, two Democratic-Republican candidates, including a leader of the Democratic Society, won by substantial majorities.

New York’s Federalists fumbled the 1796 congressional and presidential elections too. Beau Ned Livingston easily beat back a Federalist attempt to capture New York City’s congressional seat, not only solidifying Democratic-Republican control of the wards “chiefly inhabited by the middling and poorer classes of the people” but mobilizing hundreds of new voters as well.

Washington’s decision not to seek a third term set off a scramble in both parties for acceptable candidates. Democratic-Republicans united around Thomas Jefferson but had trouble agreeing on a vice-presidential nominee. Aaron Burr was the front-runner. Many Democratic-Republicans didn’t trust him, however: too young, too pushy, too devious, they said. Some knew that Burr’s notorious love of fine clothes, luxurious household furnishings, expensive wines, fancy carriages, and big houses was driving him further and further into debt. Characteristically, when he acquired the lease for Richmond Hill, the estate in Greenwich built years before by Abraham Mortier, he borrowed huge sums—from friends, from family, from law clients—to refurbish it in the opulent style with which he wished to be identified; General John Lamb alone signed more than twenty thousand dollars’ worth of Burr’s notes, a gesture he came to regret many times over. Burr even dammed Minetta Creek to create a grand ornamental pool by the main gate (approximately the present junction of Spring Street, MacDougal Street, and Sixth Avenue).

The Federalists’ problem was their standard-bearer, John Adams. Because Adams had never quite approved of Hamilton’s financial program—he once described banking as “downright corruption”—Hamilton and a corps of New York Federalists labored behind the scenes to have a narrow majority of electoral ballots cast for Thomas Pinckney, a former U.S. envoy to the Court of St. James. Adams won anyway, leaving a residue of bitterness that would in time help destroy the party. Worse yet (owing to the fact that electors didn’t yet distinguish between presidential and vice-presidential candidates) Jefferson trailed Adams by only three votes and was therefore elected vice-president. Nationwide, the Democratic-Republicans’ organizational sophistication, their mastery of electoral politics, and the mass appeal of their democratic credo had never been more obvious. Locally, their strength was underlined in the 1797 elections, when for the first time Democratic-Republicans won every seat on the city’s delegation in the state assembly.

In 1798 trouble with France abruptly derailed the Democratic-Republican express. A new right-wing government, the Directory, ousted the radical Jacobins and took immediate steps to upset the Anglo-American rapprochement. It embargoed American vessels in French ports, refused to honor bills for goods received from American merchants, and looked the other way while colonial authorities illegally plundered and confiscated American property. Squadrons of French “picaroons,” or privateers, descended on the West Indies over the winter and spring of 1795-96, taking several hundred American prizes and abusing American seamen. In December of 1796 the Directory broke diplomatic relations with the United States. The following March it announced that all neutral ships carrying enemy goods would be liable to seizure and that Americans impressed by the British navy, willingly or not, would be hanged if captured.

John Adams, just inaugurated as Washington’s successor, offered to negotiate, but the attempt fell apart when Talleyrand, the Directory’s minister of foreign relations, demanded a bribe from the American delegation. (Talleyrand’s contempt for Americans owed much to his experiences as a refugee in New York, where he had been reviled as a libertine and intriguer.) In the wake of this so-called XYZ Affair, Congress enlarged the army and navy, strengthened coastal fortifications, slapped an embargo on American trade with France and French colonies, closed American ports to French vessels, raised taxes, and authorized the arming of privateers.

By 1798 a furious quasi-war raged on the high seas. American losses to Caribbean picaroons rose steadily, and French corsairs ranged as far north as Long Island Sound to prey on American commerce, making it unsafe to sail from New York to Philadelphia without a convoy. Maritime insurance rates in New York ballooned, sometimes reaching as much as 40 percent of the value of a ship and its cargo—too high for many merchants, whose inability to carry on business sent ripples of unemployment through the city’s working population. American trade with Great Britain seemed to be in some danger too. The Bank of England had suspended cash payments, two ominous mutinies had shaken the Royal Navy, a rebellion had broken out in Ireland, and the Directory’s brilliant young general, Napoleon Bonaparte, was massing an army in preparation for an invasion of England itself.

As national opinion swung heavily against France, the Federalist Chamber of Commerce and the Federalist Common Council appropriated sixty thousand dollars for another frenzy of fortification building in New York. Congressional Federalists, sensing an opportunity to crush the Democratic-Republican opposition, meanwhile rammed through a series of bills, collectively known as the Alien and Sedition Acts, that set new standards for nativist paranoia and political repression. One, the Naturalization Act, aimed to stanch the flow of immigrants into the Democratic-Republican party by changing the residence requirement for full citizenship from five to fourteen years. The Alien Act authorized deportation of aliens suspected of “treasonable or secret” inclinations. Another measure authorized the jailing, for up to two years, of anyone convicted of publishing “false, scandalous and malicious writing” that might bring the U.S. government into disrepute. President Adams signed all this legislation into law and made it known that he was prepared to ask Congress for an open declaration of hostilities against France at any moment.

New York’s Democratic-Republicans were all but swept aside. Four thousand city residents signed a memorial to President Adams, praising his patriotism and firmness. Federalist crowds tore down a liberty cap from the Tontine Coffee House and gathered at night outside the residence of Representative Livingston, cursing Beau Ned as a Jacobin and singing “God Save the King.” Companies of eager young men began drilling on the Battery every evening between five and eight o’clock. The black cockade, once a Tory insignia, became fashionable again as a symbol of scorn for the French tricolor. Governor Jay, who had taken a leading role in the building of fortifications, won reelection easily, beating Chancellor Livingston, the Democratic-Republican candidate, by the greatest majority to date in a gubernatorial election.

Galvanized by this sea-change in the public mood, Hamilton dashed off a series of newspaper essays called “The Stand,” urging Congress to step up preparations for war, and more or less accusing the Democratic-Republican opposition of cowardice and treason. He soon got a chance to take up sword as well as pen. Washington came out of retirement to head a new fifty-thousand-man Provisional Army and tapped Hamilton for his second in command. Hamilton immediately began preparing a list of “Jacobins” for the army to round up once the shooting started.

Over the next year or so, the demoralized Democratic-Republicans assembled bravely now and then to sing the “Marseillaise.” A liberty pole or two went up in west-side neighborhoods that remained strongholds of Democratic-Republicanism and “Gallomania.” From time to time, too, Democratic-Republicans held their own in street brawls with Federalists (during one melee on the Battery somebody even beat up the president’s personal secretary). Every election nonetheless showed the party losing ground at an alarming rate.

Democratic-Republican gloom was lifted somewhat by a spunky young Irish immigrant named John Daly Burk. Expelled from the University of Dublin as a deist and republican, Burk fled to America. He arrived in New York in 1797 and made a modest name for himself with the production of two patriotic, passionately anti-British plays: Bunker Hill and Female Patriotism, or the Death of Joan d’Arc, In June of the following year, probably with the help of Aaron Burr, Burk became part owner and editor of a small weekly paper called the Time Piece and quickly turned it into one of the hottest, most widely read antiadministration papers in the country. Federalists up and down the continent soon demanded something be done to shut him up. The Time Piece, declared Abigail Adams, was a “daring outrage which called for the Arm of Government,” and quotations from Burk’s inflammatory essays helped speed passage of the Sedition Act through Congress.

Burk vigorously defended freedom of the press, winning the admiration of Democratic-Republicans in every state. They admired him all the more when, as head of the New York lodge of the United Irishmen, he repeatedly expressed his hopes for the success of an Irish rebellion against England and for a French invasion of the British Isles. But Burk’s career as a New York journalist proved short-lived. In July 1798, following the appearance of two provocative articles in the Time Piece—one intimating that President Adams had falsified a diplomatic communique, the other that Secretary of State Timothy Pickering was a murderer—Burk was arrested on charges of sedition and libel. Federal district judge Robert Troup, Hamilton’s right-hand man in the city, applauded the arrest as an opportunity to find out “whether we have strength enough to cause the constituted authorities to be respected.”

Prominent New York Democratic-Republicans, led by Aaron Burr and Tammany sachem Peter R. Livingston, stood bail for Burk. He promptly went back to hammering the administration and denouncing the charges against him as an attempt to muzzle the press. Disputes among the owners of the Time Piece caused them to suspend publication in September 1798, however, and, suspecting that the legal odds were stacked against him, Burk now offered to settle out of court. He would voluntarily leave the country, he said, if the government dismissed the case against him. Adams and Pickering agreed. When Burk boarded a ship for France six months later, British secret agents tried to grab him—or so he charged afterward—at which point “some of the best men in America” persuaded him to go instead to Virginia. He lived there under an assumed name until the expiration of the Alien and Sedition Acts several years later.

New York Federalists had no time to savor their victory over the Time Piece. Party moderates, believing there was still room for negotiations with France, made clear to President Adams that he couldn’t get a formal declaration of war through Congress. Adams, for his part, was annoyed that most of his cabinet took their cues from Hamilton, and he came to see the New Yorker’s hubristic visions of military and imperial glory as positively dangerous. “That man,” he told Abigail, “would in my mind become a second Buonaparty [sic] if he was possessed of equal power.” Though prowar Federalists fought him bitterly, Adams prevailed, and soon American negotiators were on their way to Paris, where the Directory had developed sober second thoughts about war with the United States. The Irish rebellion fizzled. Admiral Horatio Nelson smashed the French fleet in the Battle of the Nile. In the maritime quasi-war, the scales shifted in favor of the United States as a thousand-odd privateers and three new frigates—the United States, the Constellation, and the Constitution—cleared American coastal waters of enemy vessels. By the end of 1799, if not before, they controlled the Caribbean as well. In November of that year Napoleon overthrew the Directory and communicated his readiness to settle quickly. French and American negotiators came to terms in 1800.

Having reaped major political benefits from the quasi-war with republican France, New York Federalists contemplated the prospect of peace with something akin to panic. With the spring 1800 elections at hand, Hamilton appealed to the mechanic vote by arranging a legislative ticket that included a ship chandler, a baker, a potter, a mason, a shoemaker, and two grocers. However, deprived of war with France, none of the Federalists did well at the polls. Dr. Samuel Latham Mitchill, a Democratic-Republican Columbia professor, won the city’s congressional seat, taking over from Edward Livingston. All thirteen of the city’s Assembly seats went to Democratic-Republicans, giving the party a narrow majority in the state legislature. As that body chose the state’s federal electors, the sweep guaranteed that New York would back Jefferson’s second run for the presidency against Adams later that year.

No one deserved more credit for the victory than Aaron Burr. As head of the General Republican Committee, Burr prepared a roster of all voters in the city and had party workers visit every known Democratic-Republican to round up support and contributions. His house was crowded with messengers and committeemen and poll watchers who ate while they mapped strategy and napped on the floors rather than go home to sleep. Burr also introduced “fagot voting” into the party’s political repertoire during this campaign, enfranchising scores of working people who failed to meet the property requirement for voters by making them joint owners of a single piece of property. “Fagot” or “bundle” voters made all the difference in several close contests.

Suddenly, everyone in the country knew about Aaron Burr. Democratic-Republicans hailed the New Yorker as a master of the electioneering arts—a political genius who had found the fulcrum upon which the mighty Federalists could be levered from power. Even Federalists were impressed. One asked Burr how the Democrats had won the election. He replied: “We have beat you by superior Management.” When the congressional Democratic-Republican caucus nominated Jefferson for the presidency, it selected Burr as his vice-presidential running mate.

Among the Federalists, all was confusion and recrimination. In an extraordinary letter to Governor Jay, Hamilton proposed a maneuver to prevent the state legislature from choosing Democratic-Republican electors. Call a special session of the outgoing legislature, he advised Jay, and have it alter the procedure so as to ensure victory for the Federalists. No matter that everyone would see this as a brazen attempt to thwart the popular will. “In times like these in which we live,” Hamilton wrote, “it will not do to be overscrupulous.” Jay, whose sense of rectitude wasn’t so easily laid aside, refused.

President Adams blamed the loss of New York on Hamilton. That “bastard” New Yorker, he said, had organized a “damned faction” of “British partisans” who would destroy the Federalist party unless checked by moderates such as himself. Hamilton struck back with a pamphlet accusing Adams of “disgusting egotism,” “ungovernable indiscretion,” and “distempered jealousy.” As election day drew near, all semblance of unity among the Federalists vanished in a riot of charges and countercharges. “Wonderful,” declared Jefferson from the sidelines.

By mid-December 1800 all America knew that the Democratic-Republicans had captured the presidency by an electoral college margin of seventy-three to sixty-five, that the outcome in New York had been decisive, and that that outcome rested on the Democratic-Republicans’ ability to mobilize the artisans and laborers of New York City. What was not clear was who the president was. As Jefferson and Burr had each received seventy-three votes, the final decision was up to the outgoing House of Representatives, where Federalists would have the decisive role.

Jefferson or Burr? Most congressional Federalists favored Burr, but New York Federalists—notably Hamilton—warned party leaders around the country that Burr was a self-serving, unprincipled rogue and demagogue—“the most unfit and dangerous man of the community.” True, Hamilton said, Jefferson was “a contemptible hypocrite.” The Virginian was nonetheless basically decent, and manifestly the lesser of two evils. The House deadlocked for six days and thirty-five ballots, with talk of civil war growing on all sides, until the lone congressman from Delaware, a Federalist, changed his vote to Jefferson and the thing was done.

On March 4, 1801, rejoicing New York Democratic-Republicans celebrated the inaugurations of President Jefferson and Vice-President Burr. A month later George Clinton dragged himself out of retirement to lead the party in that year’s gubernatorial election. He defeated the aristocratic Stephen Van Rensselaer to win a seventh term; for the first time in his long career, he won a majority among city voters as well.

The Democratic-Republican takeover of the state legislature in 1800 vaulted yet another Clinton to a position of power in New York: the governor’s nephew and political heir apparent, De Witt Clinton. Born in 1769, De Witt was the third son of Mary De Witt and General James Clinton, an Irish-Presbyterian veteran of the Revolutionary War. He graduated from Columbia College in 1786, studied law in the office of Samuel Jones, then served a five-year political apprenticeship as his uncle’s private secretary, during which he was an active Antifederalist and became involved in upstate canal projects and real estate speculation.

In 1796 De Witt married the beautiful Maria Franklin of New York City. She was the daughter of wealthy Quaker merchant Walter Franklin, a founder of the New York City Chamber of Commerce and former owner of the Cherry Street mansion briefly occupied by President Washington. Franklin had died during the Revolution, leaving his daughter a sizable inheritance, including a country estate in Newtown, Queens.

A year after his marriage, Clinton entered politics. His commanding appearance—handsome, heavily framed, and over six feet tall, he would come to be known as the Magnus Apollo—helped him win a seat in the state assembly along with his rival-to-be Aaron Burr. In 1798 Clinton moved up to the state senate. After the Republican sweep of 1800, he was elected one of the four members of the all-powerful Council of Appointment (and its informal leader). Using his command of state patronage, he had former congressman Edward Livingston installed as mayor and rewarded a small army of party regulars with municipal and county jobs.

Behind Clinton and Burr, the Democratic-Republicans were now ready to attack the last bastion of Federalist power in New York, the Common Council. Federalists had controlled the council more or less continually since the mid-1780s, thanks in large part to ancient constraints on political participation. Under the city charter, voting in elections for the Common Council was restricted to freeholders owning property worth at least twenty pounds (fifty dollars) and to residents of the city admitted as freemen. In 1790, out of sixty-seven hundred adult white males in New York, only eighteen hundred (28 percent) were qualified to vote in municipal elections. Federalists likewise benefited from the old practice of viva voce voting. Voters in charter elections declared their preferences aloud in the presence of election inspectors; the Federalist-controlled council naturally took pains to see that at least two of the three inspectors in each ward favored that party. The candidates were there too, making careful note of who voted for whom. Journeymen, small shopkeepers, carters—men whose livelihoods might well depend on the patronage of big merchants or successful master craftsmen—needed more than a little courage to stand up for what they believed when doing so could cost them their jobs.

The formal case for changing all this was laid out by James Cheetham, an admirer of Tom Paine who fled England in 1798 and become a political journalist. His landmark Dissertation Concerning Political Equality and the Corporation of New York, published in 1800, argued with clarity as well as conviction that the city charter violated the Spirit of Seventy-six and broke every precept of republican government. The time had come, Cheetham announced, for the popular election of mayors, for secret balloting, and for the extension of the suffrage in municipal elections to every resident who could vote in assembly and congressional elections—by 1801, an estimated 62 percent of adult city males compared to the 23 percent currently eligible.

The political stakes were evident. The excluded body of voters embraced small shopkeepers, mechanics, and journeymen who were by this time overwhelmingly Democratic-Republican; if they took part in charter elections, nothing would save the Federalists from defeat. Predictably, the Federalist council refused all appeals to democratize the charter. When Democratic-Republicans turned to the state legislature for help, Federalists objected strenuously to legislative interference with the ancient “rights and privileges of the Freeholders.” One newspaper writer warned less high-mindedly that liberalizing suffrage requirements would hand the municipality over to “Irish freemen.” A reform bill passed the Assembly in March 1803, only to be tabled in the Senate.

Then, in the summer of 1803, an audit of the federal attorney’s office in New York revealed the disappearance of some forty-four thousand dollars. The head of that office was Mayor Edward Livingston. Although his own integrity was not in question, Livingston resigned both posts and moved to New Orleans. In his place the Council of Appointment named De Witt Clinton, who only the year before had been sent to the United States Senate by the state legislature. As Clinton told his uncle George, being mayor was the better job because its influence in presidential elections made it “among the most important positions in the United States” (besides, it was worth as much as fifteen thousand dollars a year).

Clinton’s return to New York helped break the deadlock over democratizing the municipal charter. In April 1804 a compromise reform bill passed both houses of the legislature. While rejecting suffrage for all taxpayers, the bill enfranchised twenty-five-dollar renters and introduced the secret ballot into municipal elections. It also defined “freemen” as all freeholders and rentpayers eligible to vote—to all intents and purposes abolishing freemanship as a privilege distinct from the ownership of property. Cheetham hailed the new law as a “Second Declaration of Independence to the Citizens of New York.” And in that year’s more democratized municipal elections, the Democratic-Republicans added the Common Council to their list of conquests.

Whipped by Jefferson and now evicted from City Hall, many party elders—John Jay, Rufus King, Gouverneur Morris, Richard Varick, Philip Schuyler, Comfort Sands, and others—decided to quit public life altogether until the voters came to their senses. After twenty-five years of struggling to contain the democratic impulses unleashed by the Revolution, they had had enough.

Other, typically younger, Federalists drew the opposite conclusion from defeat. As Hamilton advised the King, do not lose hope that “the people, convinced by experience of their error, will repose a permanent confidence in good men.” Elections clearly had their drawbacks, but good men had to go along or they would be doomed to political extinction (a point Hamilton had been making since the early eighties). If they lost this time around, there was no alternative other than to try again the next. Even in New York, after all, Federalists continued to enjoy a strong following in certain trades, and they hadn’t yet fully tapped nativist hostility to the foreign-born, especially Irish, immigrants crowding into the city.

In 1801, accordingly, Hamilton helped establish the New York Evening Post as a party organ, with William Coleman as editor. The following year he unveiled his plan for a new, nationwide Federalist organization to be called the Christian Constitutional Society. As he envisioned it, the society would finance the publication of newspapers and pamphlets in every part of the country. It would “promote the election of fit men.” It would also encourage—especially in “the populous cities”—the formation of clubs, charities, and schools to uphold the true principles of Christianity and the United States Constitution. Initial reactions to the idea were cool. There is no telling where it might have led, however, for two years later Hamilton was dead.

Early in 1804 George Clinton, governor of New York for twenty-one of the last twenty-seven years, announced his intention not to seek an eighth term (rumor had it that he would replace Burr as Jefferson’s vice-presidential running mate later in the year). The state’s Democratic-Republicans, now divided by mushrooming hostility between proand anti-Burr factions, couldn’t agree on a replacement. The Clinton-Livingston wing put up Chief Justice Morgan Lewis; Burrites raised their leader’s standard. Jefferson denounced Burr’s candidacy. So did Hamilton, who, reiterating his belief that Burr was a scoundrel, threw his support to Lewis. Burr narrowly carried New York City, but Lewis won by a huge margin statewide.

His political career in shambles, Burr lashed out at the man who had thwarted him ever since their days as young officers on Washington’s staff. Soon after the election he wrote to Hamilton demanding an explanation for a certain newspaper report that he, Hamilton, “looked upon Mr. Burr to be a dangerous man, and one who ought not to be trusted with the reins of government.” Hamilton let it be known, through an intermediary, that his remarks “turned wholly on political topics, and did not attribute to Col. Burr any instance of dishonorable conduct, nor relate to his private character.” Burr nevertheless demanded an “interview” on the field of honor. Hamilton’s views on dueling had shifted after his eldest son was killed in a political duel only three years before. To run from Aaron Burr, however, was unthinkable. He accepted the challenge.

Early on the morning of July 11, 1804, Hamilton and Burr, accompanied by their seconds, crossed over to Weehawken, New Jersey, on the west bank of the Hudson opposite the present foot of 42nd Street. Their seconds cleared a proper site near the shore, loaded the pistols, and positioned the two men a mere ten paces apart. At the signal, Burr slowly raised his weapon, aimed, and fired. Hamilton, who had previously declared his intention to let Burr get off the first shot, fell mortally wounded. Burr fled the scene at once. Hamilton’s seconds brought him back across the river in a small boat, docking at the foot of what is now Horatio Street in Greenwich Village. He was carried to the nearby home of William Bayard, where he died the next day after what his doctor termed “almost intolerable” suffering.

Hamilton’s funeral two days later was a poignant reminder of the political consensus he had once inspired in New York—and had subsequently done so much to destroy. The Democratic-Republican Common Council instructed “all classes of inhabitants” to suspend their usual business and ordered muffled bells to toll from dawn to dusk. At noon a long, somber funeral cortege wound its way through the streets toward Trinity Church. Every social group and civic organization—military officers, students of Columbia College, merchants, attorneys, the Society of Cincinnati, the General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen, even the Tammany Society—was represented in the procession, trailed by a mass of “citizens in general.” Warships in the harbor fired their minute guns. Merchant vessels flew their colors at half-mast. Gouverneur Morris delivered a moving funeral oration at Trinity.

While tributes to Hamilton poured in from all over the country, Burr kept out of sight. Two weeks after the duel, facing a murder indictment and fearing his house would be attacked by a mob, he slipped out of town into obloquy everlasting.