A year or so after Evacuation Day, Robert R. Livingston bought a house on Bowling Green—only to discover that the municipal corporation meant to sell off a dozen nearby lots fronting the Hudson River for commercial development. This was a terrible mistake, Livingston warned Mayor James Duane. The corporation should stop construction along the Hudson River waterfront, not encourage it. Ban new streets and wharves. Let the “opulent persons” living in this part of town close off Greenwich Street and extend their gardens all the way to the river. Thus, “instead of the noxious odor of warves & dram shops they will in the midst of a town enjoy the pure air of the country—Few among them are so tasteless or so interested [i.e., selfish] as to permit the sight of wretched houses smokey chimneys & dirty streets to shut off their prospect of one of [the] finest rivers in the world.”

Livingston’s attempt to find a home insulated from the seamier aspects of urban life was as yet far from typical among well-to-do New Yorkers. Like master craftsmen, they were accustomed to living and working in the same building, and the boundaries between “family” and “business” life, between “private” and “public” spaces, were highly porous. Every day their families rubbed elbows with customers and clients, clerks and apprentices, servants and slaves. Indeed the households of prominent merchants ranked among the largest work establishments of the eighteenth century. Typically the first floor contained a store or counting room, with patrons, employees, and family members alike moving freely through adjacent hallways and rooms. Not even the second-floor drawing rooms and bedrooms were ever completely sequestered from this traffic, and the third would be filled with children, clerks, and servants engaged in domestic as well as business-related chores. It was the same story out of doors, for commercial neighborhoods, like commercial households, were spaces shared by all classes. In 1790 merchants constituted only a third of the residents of the dockside area. The majority of their neighbors were artisans, shopkeepers, and the laboring poor.

After 1790, however, Livingston’s peers began to follow his example. The frequency of pestilential diseases, the increasing tempo of business, the construction of ever bigger warehouses, the conversion of older residences into boardinghouses, the proliferation of artisanal workshops, and the profusion of shanties and cellars filled with impoverished Irish immigrants—all of these transformed the waterfront streets that wealthy New Yorkers had called home for a century or more. So, too, the impact of republicanism on class relations meant that gentlemen and their wives could no longer command an easy deference from the mechanics, sailors, and laborers living nearby. Thus, like Livingston, they decided to look for houses in less congested and troublesome parts of town.

More precisely, they decided to live and work in different places. Merchants transferred their countinghouses to their warehouses near the East River wharves, using the ground floors to sell and display goods while keeping the upper floors for storage. They then moved their families across town, into new residences whose richly ornamented interiors, generous yards, and many amenities—carriage houses, smokehouses, icehouses, liquor vaults, private pumps—were clearly designed for domestic isolation rather than trade. Once underway, the movement to separate home and work advanced rapidly. In 1800 one in ten merchants or professionals listed separate houses and workplaces in city directories. By 1810 better than half did so.

The west side of Manhattan meanwhile became New York’s most exclusive quarter. Not only did this part of town lie within convenient walking distance of coffeehouses, storehouses, and offices, but thanks to recent municipal improvements it was acquiring certain unique charms as well. After razing Fort George, the city had extended Broadway through the site, erected a bulkhead from Battery Place to Whitehall Street, and installed a spacious walk along the water’s edge shaded by elm trees. As early as 1793 civic boosters were hailing the emerging little park as “one of the most delightful walks, perhaps in the world,” much frequented by the city’s “genteel folk.” Another local attraction was nearby Bowling Green, recently refurbished with brick or fieldstone sidewalks and planted with stately Lombardy poplars to replace trees lost during the war.

As early as 1786 a notice in one of the local papers called lower Broadway “the center of residence in the fashionable world,” and over the next decade it would be lined with four-story Federal-style mansions occupied by Jays, Gracies, Delafields, Macombs, Lawrences, and Varicks. (Hamiltons, Morrises, and Hoffmans lived close by on Whitehall, Beaver, and lower Greenwich streets.) “There is not in any city in the world a finer street than Broadway,” La Rochefoucauld proclaimed in the mid-nineties. “From its elevated situation, its position on the river, and the elegance of the buildings, it is naturally the place of residence of the most opulent inhabitants.”

The “opulent inhabitants” hadn’t entirely escaped their less affluent fellow citizens, for members of other classes lived on adjacent streets, virtually next door. Greenwich Street, for instance, was home to numerous artisans and shopkeepers as well as a small population of free blacks. Petty crime was a recurring problem, and by the turn of the century weekend crowds of working people converged on the Battery. There, as Washington Irving observed condescendingly, “the gay apprentice sported his Sunday coat, and the laborious mechanic, relieved from the dirt and drudgery of the week, poured his weekly tale of love into the half-averted ear of the sentimental chambermaid.” Newspapers deplored the parties of naked boys and young men who could always be seen swimming off the Battery in hot weather—an offense against refined sensibilities that the Common Council struggled for years to eradicate. Far more disturbing was the neighborhood’s vulnerability to disease. In 1799 Elizabeth Bleecker, who lived on lower Broadway, was shocked when a black man dying of yellow fever “came up our alley and laid himself down on the ground.”

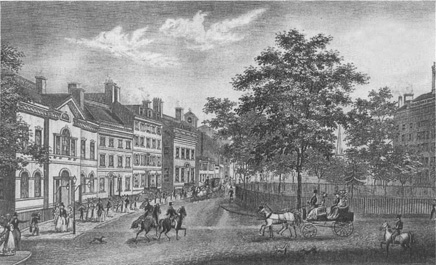

In the early nineteenth century, Bowling Green was a center of fashionable society in the city. The fence encircling the little park still stands. (© Museum of the City of New York)

These plebeian intrusions didn’t precipitate another patrician exodus, but some merchants, professionals, and prosperous master artisans did begin to drift a bit farther north, searching for houses that (as one builder advertised in 1803) were “in so healthy and airy a situation as to render retirement to the country unnecessary during the summer.” Streets running west to the river were popular—Vesey, Barclay, Park Place, and Murray—especially where they fronted open spaces like the campus of Columbia College. Broadway north from Cortlandt Street attracted the likes of John Jacob Astor, who settled on Broadway in 1803, along with assorted Kings, Rutherfords, and Roosevelts. After 1806, when Trinity began requiring its tenants to build with brick rather than wood, genteel housing reached as far as Chambers Street, on the north side of the Park where City Hall was under construction. Indeed it was widely assumed, as the Common Council asserted, that “the Elegance and situation of this Building” would so increase the value of nearby real estate that it was destined to be “the center of the wealth and population of this City.”

When the Englishman John Lambert passed through New York in 1807, the milelong stretch of Broadway from Bowling Green to the Park was firmly established as the axis of respectable society. At the lower end of the street, rich merchants and lawyers and brokers lived side by side in rows of “lofty and well built” town houses. Above them ranged block after block of “large commodious shops of every description . . . book stores, print-shops, music-shops, jewelers, and silversmiths; hatters, linen-drapers, milliners, pastry-cooks, coachmakers, hotels, and coffee-houses.” From eleven to three every day, Lambert remarked approvingly, the whole of Broadway from Bowling Green to the Park was the “genteel lounge” of New York, “as much crowded as the Bond-street of London” with strolling ladies and gentlemen turned out in the latest European fashions.

Few wealthy residents as yet were prepared to venture farther north, however—as Trinity Church found to its cost. Inspired by the soaring real estate market, the ever alert vestrymen decided to develop part of the old church farm near the Hudson River into an elite residential square of the kind that graced London’s West End. In 1807 the church obtained Common Council permission to enclose a grassy pasture bounded by Varick, Beach, Hudson, and Laight (near what is now the entrance to the Holland Tunnel). To lure the right kind of people so far from the center of town, the vestry hired John McComb to put up a suitably refined chapel in honor of St. John, facing the proposed square from the east side of Varick Street. McComb directed the building of St. John’s between 1803 and 1807 while continuing to supervise construction of City Hall, and it proved to be a gem of patrician neoclassicism. Its pedimented portico, supported by four Corinthian columns and topped by a 214-foot clock tower and steeple, made it the most imposing church in the city; its bells could be heard as far south as the Battery and as far north as Greenwich.

Delighted, the vestrymen of Trinity began laying out, grading, and planting their development on the opposite side of Varick. But Hudson Square, also known as St. John’s Park, failed to attract settlers. The vestry’s terms—ninety-nine-year leaseholds on lots surrounding the park—didn’t appeal to the city’s property-savvy upper classes, and except for a handful of stonecutters and other artisans who settled nearby, McComb’s church was left virtually alone in its pasture for another twenty years.

Genteel families would nonetheless venture farther north for summer homes. Some well-to-do city merchants even built or rented country estates for their families on Brooklyn Heights, from which Washington had so narrowly escaped a scant twenty years before. There they had everything—cool ocean breezes, stunning views of the harbor, and ready access to their places of business. “The men go to New York in the morning,” it was said, “and return . . . after the Stock Exchange closes.” Vacationers also flocked to places like Governors Island, Harlem, and even New Jersey; in 1797 President John Adams came up to Eastchester in the Bronx to escape the yellow fever in Philadelphia.

When James Watson, a wealthy merchant, decided to enlarge his Federal style residence on State Street, he hired John McComb, who embellished it in 1806 with a distinctive curved porch and graceful Ionic columns, purportedly carved from ships’ masts. (Watson’s house still stands, sole survivor of an entire block of elegant town houses that once faced the Battery.) The basic elements of the Federal style—brick facade, high stoop, recessed front door, discreet trim—were nonetheless inherently simple, and from the street it wasn’t usually so easy to gauge who occupied a residence or how it was being used. Indeed, the unpretentiousness of its dwellings was a matter of some pride to an elite that took republicanism seriously and eschewed much of the “reserve and haut ton so prevalent in the old country,” as visiting British astronomer Francis Baily put it.

A Federal-style townhouse, therefore, could easily be sheltering people in relatively modest circumstances. Between 1790 and 1820 master builders erected hundreds, probably thousands, of such residences for the prosperous master craftsmen, smaller merchants, and up-and-coming professionals who constituted the city’s middling classes. Other, almost identical domestic structures accommodated commercial or professional operations or had been recycled into boardinghouses. This very uniformity obscured significant and growing differences in wealth and power among residents of the city, and veiled as well important changes taking place within the buildings themselves.

One such change was the expanded use of genteel homes for socializing. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, well-to-do New Yorkers were accustomed to “entertaining” one another in taverns and coffeehouses (with results often verging on the riotous). They continued to do so in the early nineteenth century, taking advantage of the more commodious public rooms in new city hotels to host gatherings of the St. Andrew’s, St. George’s, St. David’s, Friendly Sons of St. Patrick, the German, St. Stephen’s, and New England societies. In 1792 a number of New York gentlemen founded what was perhaps the nation’s first country club, the exclusive Belvedere House, at what is now Cherry and Montgomery streets. It boasted an octagonal ballroom, two private dining parlors, two card rooms, a barroom, and overnight accommodations for members. Dancing-assemblies continued to play a crucial role in determining social status—an invitation from the City Assembly was more highly prized than one from the rival Juvenile Assembly. Subscription concerts were another draw, and at least seven fashionable musical companies—the New York Musical Society, the St. Cecilia Society, the Columbian Anacreontic Society, the Harmonica! Society, the Polyhymnian Society, the Philharmonic Society, and the Euterpean Society—flourished at one time or another during the eighties and nineties. Equally prestigious was the fancy new (1798) two-thousand-seat playhouse on Chatham Street (now Park Row) facing the Common. Designed by emigre engineer Mark Isambard Brunei, the Park Theater, as it came to be known, cost a princely $130,000 and was specifically calculated for the comfort and convenience of the city’s respectable classes.

At the same time, however, the disappearance of clerks, clients, and customers from the genteel household facilitated the redeployment of its interior spaces for less public forms of socializing. Formal parlors, drawing rooms, and dining rooms acquired new prominence as the setting for gentlemen to entertain business associates as well as for those events—suppers, teas, receptions—with which their families solidified ties to others of similar wealth and status. With this shift, too, came a heightened emphasis on the role of upper-class women as domestic managers. On New Year’s Day, when city gentlemen threaded their way through the streets to call at one another’s homes, it was their wives and daughters who remained behind to serve food and drink to visitors—assisted by a growing domestic labor force. The ensuing demand for household help was largely responsible for the brief revival of slavery during the 1790s, after which it fostered the growth of “intelligence offices,” recruiting agencies for waged servants. By the early 1800s, upper-class women in New York were expected to hire, train, and supervise swarms of household workers, overwhelmingly female, who cooked, served, cleaned, washed, drew water, hauled wood, mended clothes, minded children, and emptied the slops. It wasn’t easy, either, as newly wed Eliza Southgate Bown discovered in 1803. “Mercy on me,” she cried, overwhelmed by the myriad details of setting up a proper home, “what work this housekeeping makes! I am half crazed with sempstresses, waiters, chambermaids, and everything else—calling to be hired, enquiring characters, such a fuss.”

When the federal capital departed for Philadelphia, Manhattan’s intellectual life suffered a grievous setback. Losing Thomas Jefferson would, alone, have been a blow to any cultured community. But New York had lost the entire federal establishment, something it could ill afford for, as one French traveler remarked, “this city does not abound in men of learning.”

During the 1790s, however, would-be New York philosophes—primarily youthful merchants and professionals who aspired to be men of letters as well as men of affairs—began to create associations to incubate a worthy municipal culture. In the parlors of their new town houses, and in Manhattan’s taverns and coffeehouses, earnest young men gathered to debate and discuss literary, political, and scientific ideas in their Uranian, Horanian, Calliopean, Law, and Philological societies, or their Sub Rosa, Turtle, Black Friars, and Belles Lettres clubs.

The most fruitful of these group efforts at civic and self-improvement was the Friendly Club, creation of Elihu Hubbard Smith, a twenty-two-year-old, Yale-educated physician who came down to New York from Connecticut in 1793 to join the staff of the New York Hospital. Smith soon became acquainted with a handful of other ambitious men just embarking on what would prove to be distinguished careers. Among them were William Woolsey, future financier and corporate president; James Kent, soon to be one of America’s leading legal scholars and chancellor of New York State; and William Dunlap, who as playwright, theater manager, and drama critic would help establish the professional stage in the city.

In addition, Dr. Smith linked up with Dr. Samuel Latham Mitchill, Manhattan’s closest approximation to a native renaissance man. In 1797 Smith and Mitchill collaborated on launching the Medical Repository—the country’s first professional journal of medicine, and a source of original scientific essays, book reviews, and reports on scholarly work in Europe. The versatile, Hempstead-born Mitchill had attended King’s College, received his medical degree from Edinburgh in 1786, then served as surgeon general of the state militia. After the Revolution he became “Professor of Natural History, Chemistry, Agriculture, and other Arts Depending Thereon” at Columbia; cofounded, with his good friend Robert R. Livingston, the New York Society for Promoting Agriculture, Arts, and Manufactures (1791); carried out the first geological survey of the Hudson River Valley; promoted sanitary reforms in the city; helped found the College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1807; and served, as an ardent Jeffersonian Republican, three terms in the state assembly and thirteen years as U.S. congressman and senator.

Sometime near the end of 1793, Smith’s formidable coterie formed themselves into the Friendly Club and embarked on a program of intellectual improvement. Once a week for the next five years, members assembled in one another’s private lodgings or in taverns to discuss literature, science, philosophy, and politics. As inhabitants of what Smith liked to call the “republic of intellect,” they avidly explored the most progressive ideas of the age. They pored excitedly over William Godwin’s Inquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793), an electrifying attack on monarchy and property. They rejected the “vulgar superstitions” of Christianity, according to James Kent, and cast their lot with deists.

One of the most popular subjects to occupy the all-male membership of the Friendly Club was the rights of women. The works of European feminists were readily available in the United States by the mid-nineties. Many Manhattanites thrilled to Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), her generation’s most articulate statement of what women deserved and what they might become with equality. Only a year or two after its initial publication, pamphlets for and against Wollstonecraft were standard fare in New York bookshops. Newspaper and magazine editors openly competed for readers of “the fair sex” by reprinting excerpts from the Vindication and running lengthy exchanges between its critics and defenders. Articulate and well-informed women sent in essays to local newspapers and magazines, disputing offensive characterizations of female intelligence, attacking the sexual double standard, challenging legal and political discrimination, and questioning the institution of marriage. In 1796 Wollstonecraft’s partisans got their own periodical, the Lady and Gentleman’s Pocket Magazine of Literature and Polite Amusement, which promoted women’s rights with zeal, though not profitably enough to keep it from going out of business after a few issues.

In 1798 the Friendly Club persuaded Charles Brockden Brown to move up from Philadelphia. Described sometimes as the first American to make a profession of literature, Brown was a catch—an authentic man of letters, widely read as well as sociable, whose views owed much to both Wollstonecraft and Godwin. During his three-year residence in the city, besides publishing two novels with female protagonists, Wieland and Ormond, Brown produced an influential women’s rights tract entitled Aleuin: A Dialogue.

Against this background, well-to-do New York families began to place a higher priority on the education of young women. How, it was asked, could respectable wives and mothers contend with their new social and managerial responsibilities without some degree of formal schooling? How could they inculcate republican virtue in their children without some knowledge of history, natural science, and philosophy? Aaron Burr, who had pronounced Wollstonecraft’s Vindication “a work of genius” and vowed to read it aloud to his wife, had their daughter, Theodosia, tutored in Latin and Greek; at the age of nine she was reading two hundred lines of Homer and half a dozen pages of Lucian every day. The Jays, Kents, Duanes, and other prominent families shipped their daughters off to one or another of the many new female boarding schools that had sprung up around the country since independence (the three most favored by New Yorkers being the Moravian Young Ladies Seminary in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, the Philadelphia Young Ladies Academy, and Miss Pierce’s School in Litchfield, Connecticut). Still other well-to-do New York families came to depend upon the academy for women founded in 1789 by Mrs. Isabella Graham, a widow recently arrived from Scotland. The earliest institution of its kind in the city’s history, “Grandmother” Graham’s school was quartered in an old Georgian mansion on lower Broadway, a reputable address for what was still considered daring work.

“The history of the City of New York,” Elihu Hubbard Smith once wrote with some asperity, “is the history of the eager cultivation & rapid increase of the arts of gain”; its residents think of nothing but “Commerce, News, & Pleasure.” From the outset, accordingly, he and other members of the Friendly Club made a special point of disseminating a wide range of literary and scientific “information” to the reading public. By 1793 or 1794 they were providing all the original articles for the New York Magazine, a publication launched in 1790 by Thomas and James Swords and edited initially by Noah Webster. The journal featured a melange of materials ranging from sentimental romances to essays on the rights of man and woman by Godwin and Wollstonecraft. It wound down in 1797, about the time that the members of the Friendly Club disbanded. A number of former members founded the Monthly Magazine and American Review in 1799, the editorial philosophy of which closely followed that of the New York Magazine; it too sputtered out within a year. In 1801 Hocquet Caritat, the emigre proprietor of the most influential bookstore in town, established a “Literary Assembly” in a reading room of the old city hall. Caritat hoped it would become a place where writers, lawyers, scientists, doctors, and clergymen would come to discuss books and ideas, but like the efforts of the Friendly Club, it made little headway against the city’s preoccupation with money making—even after Caritat took the radical step in 1803 of inviting women to attend.

The struggle against municipal materialism finally began to bear fruit when it engaged the formidable energies of city inspector John Pintard. For years, inspired by the example of the Massachusetts Historical Society (1791), Pintard had advocated the creation of a similar institution in New York to improve its intellectual and cultural tone. In 1804 he assembled a group of Friendly Club alumni, merchants, attorneys, and clergymen to found the New-York Historical Society. Its mission was “to collect and preserve whatever may relate to the natural, civil or ecclesiastical History of the United States in general and of this State in particular.”

Historical preservation—especially of relics and records—held special meaning for men who had seen the city’s only two substantial libraries destroyed during the Revolution—that of Columbia College, and the New York Society Library, of which Pintard had been a trustee. The latter had made a comeback, and by the time it moved into its new quarters on Nassau Street in 1795 it owned over five thousand books, but it remained a general reading library for well-to-do shareholders. Pintard hoped the Historical Society would in time “become like the extensive Libraries of the Old World inestimably valuable to the erudite Scholar.”

The Historical Society swiftly attracted prestigious supporters, including Dr. Samuel Latham Mitchill, Dr. David Hosack (physician, botanist, and founder in 1801 of the Elgin Botanical Gardens), members of old New York families (like Peter Gerard Stuyvesant, the director’s great-great-grandson), judicial luminaries (like state attorney general Egbert Benson, the society’s first president), and political leaders (like Governor Daniel D. Tompkins and Mayor De Witt Clinton, who provided the group with rent-free quarters in Federal Hall on Wall Street). Though its finances were precarious, the Historical Society quickly published an Address to the Public (1805) calling for donations of materials and for answers to queries concerning points of local and national history. In 1809—the year the society was incorporated and in which it purchased Pintard’s own library—members gathered to commemorate the bicentennial of Henry Hudson’s voyage by listening to the Rev. Dr. Samuel Miller’s Discourse on the Discovery of New York, followed by a banquet at the City Hotel. Two years later, the Historical Society issued the first volume of its Collections, which featured documents on city life under the Dutch and the never-before-printed Duke’s Laws of 1665.

As it happened, Pintard’s labors on behalf of the Historical Society coincided with a mounting interest among wealthy New Yorkers in painting and the fine arts. Some of the country’s foremosts artists—Ralph Earl, James Sharpies, Charles Willson Peale, Gilbert Stuart, John Trumbull, John Wesley Jarvis—all set up shop in the city at one time or another in the eighties and nineties. Prosperous burghers, as the poet William Cullen Bryant later recalled, “began to affect a taste for pictures, and the rooms of Michael Pfaff, the famous German picture dealer in Broadway, were a favorite lounge for such connoisseurs as we then had, who amused themselves with making him talk of Michael Angelo.” What was more, reformers and civic improvers like Pintard began to sense that art—the right kind of art, under the right kind of circumstances—could also help lift the sights of New Yorkers and teach them virtues vital to a republican society.

In 1802 Chancellor Robert R. Livingston and his brother Edward, the newly appointed mayor, raised several thousand dollars to establish the New York Academy of the Fine Arts (later the American Academy of Fine Arts), with none other than John Pintard as its first secretary. The academy was not an association of artists but of wealthy patrons. Its purpose, Mayor Livingston explained, was to expose New Yorkers to the best European sculpture and painting, thereby affirming “the intimate connection of Freedom with the Arts—of Science with Civil Liberty.” It would also be “useful and ornamental to our city.” That proved overly optimistic. The academy’s first exhibition, which opened in the summer of 1803 at the Greenwich Street Pantheon (formerly Rickett’s Equestrian Circus), was a disappointment. Consisting mostly of plaster casts of “the great remains of Antiquity” owned by the Louvre, it failed to attract popular interest and was cut short by that year’s epidemic of yellow fever. John Vanderlyn, a young artist introduced to New York art patrons by Aaron Burr, was dispatched to Europe to make more casts and paint copies of Raphael, Caravaggio, Titian, Rubens, and other Old Masters. The academy’s shareholders, businessmen ill-prepared to promote art appreciation among the general public, began to bicker among themselves, however, and the academy soon languished.

Its prospects brightened again in 1804, when John Trumbull returned to New York to take over as director. Trumbull was immediately swamped with commissions, private as well as public. Between 1805 and 1808 he produced a series of portraits for City Hall that included such local luminaries as De Witt Clinton, James Duane, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Peter Stuyvesant, Richard Varick, and Marinus Willett (all of which would hang alongside his George Washington in New York, painted back in 1790). Yet Trumbull paid more attention to his own work than to the academy’s affairs, and after his departure in 1808, the organization again went into decline. Its officers ceased to meet, and by 1815 its collections were put in storage.

The academy’s demise did not mean, on the other hand, that the new Historical Society would have to carry on by itself. Business-minded New York wasn’t ready for art, but neither were men like John Pintard ready to abandon the campaign for municipal uplift and enlightenment.

It wasn’t accidental that Pintard, Clinton, Mitchill, Dunlap, and many of their friends were also active in Freemasonry, an international movement devoted to personal betterment, fraternal loyalty, and the diffusion of knowledge to dispel (as Mitchill put it) “the gloom of ignorance and barbarism.” Under the leadership of Robert R. Livingston, grand master from 1784 to 1801, the Masons founded ten lodges in the city. Arguably the most influential was the Holland Lodge, whose masters included both Clinton and Pintard, and whose members included such eminent and powerful residents as John Jacob Astor, Cadwallader D. Golden (grandson of the colonial governor), and Charles King (president of Columbia College).

De Witt Clinton, in particular, was an ardent Mason. From master of the Holland Lodge (1794) he rose to become grand high priest of the Grand Chapter, grand master of the Grand Encampment of New York, and grand master of the Knights Templar of the United States, the highest office of the Cerneau Scottish Rite body. What attracted him, apart from the opportunity lodge work gave him to establish links with powerful men throughout the city, state, and nation, was the fraternity’s lineage of descent from “scientific and ingenious men” and its commitment to having each member “devote to the purposes of mental improvement those hours which remain to him after pursuing the ordinary concerns of life.”

Even when his public life was at its busiest, Clinton found time for an impressive range of intellectual interests. He belonged to, and often led, the most prestigious literary and learned organizations of his day. He studied botany, zoology, geology, ornithology, ichthyology, and chemistry, and his published papers, which earned the praise of scientific societies throughout the United States and Europe, covered such disparate subjects as the fish of New York State, Iroquois language and customs, archaeology, and the cockroach. Justifiably proud of his achievements, Clinton could describe himself with aplomb—others called it insufferable vanity—as “distinguished for a marked devotion to science; few men have read more, and few men can claim more various and extensive knowledge.”

Clinton was never content with private scholarly pursuits, however, and he was among the first New Yorkers to say that people of his class had a duty to improve the lives of others. As early as 1794, in an address to the Black Friars Club, he summoned patrician New Yorkers to reject “selfishness” and enlist in the cause of “disinterested benevolence.” They should rise “from the couch of affluence and ease,” he said, not only to encourage the “polite arts and useful sciences” but to build schools and hospitals, care for the poor, and modernize the penal system. This was an idea practically unknown in New York before independence, and it drew heavily on Clinton’s identification with the Masonic movement (“the most antient benevolent institution in the world” he called it), on his frank admiration for contemporary British reformers, and on his personal connections with such prominent Quaker philanthropists as Thomas Eddy and John Murray Jr. (both of whom he met through his wife, also a member of the Society of Friends). What Clinton added was an emphasis on the urgency of benevolence —not simply to rectify social ills but also to overcome the privatism of the propertied classes and reaffirm their legitimacy.

During the 1790s and 1800s, Clinton and other well-to-do New Yorkers would create a battery of humanitarian and educational associations to improve the lot of their fellow citizens. In time, their membership rolls comprised a who’s who of the city’s most successful and influential citizens—merchants, lawyers, bankers, brokers, physicians, clergymen, Columbia College faculty—many of whose names turn up over and over again in an astonishing variety of causes.

As a rule, these associations were solidly Protestant and determinedly bipartisan. (The Society for the Promotion of Agriculture, Arts, and Manufactures, for example, was founded in the early nineties by George Clinton, John Jay, Philip Van Cortlandt, Edward Livingston, and James Duane, among others, a judicious balancing of political tendencies and temperaments that would be duplicated often in years to come.) Nominally private, they often received generous support from both municipal and state governments—as well they might considering the roster of governors, mayors, legislators, assemblymen, and other public officials who were their founders and managers. They were guided by an awakening sense of civic pride, by compassion, and by an absolute certainty that the best people ought to toil, directly and personally, for the public good—as they denned it. “What a field our large city presents for active exertions & useful improvements!” exulted John Pintard.

No one was more active than Pintard himself. After leaving the office of city inspector in 1809, he became secretary of the Mutual Insurance Company, his sole source of income for the next twenty years (during most of which time he and his family lived frugally in rooms above the company’s Wall Street office). It was abundantly clear by then, however, that his real work lay in benevolence and philanthropy. In all, over the course of thirty-odd years, he would be the prime mover in dozens of similar organizations.

Never far from Pintard’s mind was the knowledge that men such as himself were all too scarce in New York. The city’s wealthiest residents were on the whole unable or unwilling “to attend to the multiplied demands on humanity & benevolence,” he once told his daughter. “Here, these duties fall oppressively heavy on a few public spirited citizens.” But in the end virtue was its own reward. “The further I go down the hall of life,” he added modestly on another occasion, “the more I rejoice in the retrospect of being a coadjutor in some of our great benevolent and charitable institutions and that when I depart—it will cheer me that I am leaving the world better than I found it.”

When genteel reformers like Pintard talked about leaving the world a better place, they meant, above all, ameliorating the misery of their city’s lower classes. Pintard himself admitted that this mass of humanity—immigrants, working poor, the aged and infirm, blacks, widows, orphans—seemed hardly worth the trouble. They were, he said censoriously, “improvident, careless, and filthy.” Yet if Pintard and his colleagues believed anything, they believed in what De Witt Clinton had called “the progressive improvement of human affairs.” Shown the way, they thought, even the meanest people (the bulk of them, anyway) could become decent, productive citizens. This wasn’t simply altruism. A permanent class of paupers, unincorporated into legitimate political and social institutions, posed a threat to the republic.

In this spirit, the Society for the Relief of Distressed Debtors set out in 1787 to provide short-term assistance to some of the city’s neediest residents. Its managers—almost exclusively business and professional men—would include, at one time or another, such luminaries as Clinton, Pintard, Eddy, Dr. Hosack, and Divie Bethune, a wealthy Scottish merchant. At first, the society’s aim was to provide occupants of the debtors’ prison with food, blankets, clothing, fresh water, and firewood. This was no small task. Over five hundred debtors were arrested in New York County every year. By posting a bond with the sheriff, those with means could be released to live within prescribed “gaol limits.” Those without means, rarely fewer than a hundred at a time, were locked up and required by law to supply their own necessaries. Conditions in the prison verged on the nightmarish.

In the later 1790s the society distributed food to indigent victims of the yellow fever, and after 1800 its charitable horizons widened steadily. In 1802 the society opened a permanent “soup house,” near the jail on Frankfort Street, that dispensed soup to the urban poor at four cents a quart—or free, during epidemics and depressions. New Yorkers took to calling it the Humane Society (a change of name that became official in 1803). During the hard winter of 1804-5, their Frankfort Street operation, and a second “soup house” they opened on Division Street, distributed eighty-four hundred gallons of soup to residents of the city’s poorest wards. The group also dispensed soup tickets for handing out to street beggars in place of money and provisions, lest the poor convert such offerings into liquor.

The city’s doctors had meanwhile taken steps to provide impoverished residents with medical care. In 1791, inspired by similar projects in Europe and Philadelphia, the Medical Society opened the New York Dispensary on Beekman and Nassau streets. Supported by private donations, it treated over two thousand patients in its first five years. In 1791, too, the state provided money to reopen New York Hospital, originally founded in the 1770s but soon forced to suspend operations because of a devastating fire and the turmoil of war. Now designated “the public hospital,” it provided free treatment to the “sick poor” from immigrant ships and the city’s emerging slums. It housed the first nursing school in the United States, established in 1798 by the Quaker physician Valentine Seaman, and soon after the turn of the century it absorbed another charitable institution, the Lying-in Hospital, which had been founded in 1799 to provide care for impoverished pregnant women. In time, and at federal expense, the hospital also began to take in indigent seamen from the navy and merchant marine.

Genteel ladies too immersed themselves in philanthropic work among the poor and laboring classes. In 1797, by which time she was earning a comfortable income from her school, Isabella Graham joined forces with others, notably Elizabeth Ann Seton, wife of a successful merchant, to organize the Society for the Relief of Poor Widows with Small Children. Applicants for assistance were to receive only “necessaries,” never money, and only after “particular enquiry” had determined their moral fitness; no assistance would be given, either, unless younger children were sent to school and older ones placed into trades or into service with “sober virtuous families.” Efficient and resourceful, the society expanded quickly. Within two years it was supplying firewood, food, shoes, clothing, and meal tickets to 150-odd widows and some 420 children.

Mrs. Graham followed up this project with a workhouse for needy women. After a protracted campaign for municipal support, she and her followers, organized as the Society for the Promotion of Industry, founded the House of Industry and won an annual appropriation of five hundred dollars from the legislature. At one time or another over the next decade (it failed in 1820), the House of Industry employed more than five hundred women as tailors, weavers, spinners, and seamstresses.

These and other female charities enabled women (well-to-do women, at any rate) to break the male monopoly on the city’s public life and assert for the first time a separate and distinct role in municipal affairs. Although respectable to a fault and indifferent to women’s rights as such, these initiatives worried even reform-minded men. Women calling meetings, women running organizations, women raising money, women contending with local officials about budgets and leases and regulations—where would it end? Many men nodded approvingly when Bishop John Hobart of New York publicly denounced the whole idea “of females laying aside the delicacy and decorum, which can never be violated without the most corrupting effects on themselves and public morals” to become agents of social change.

Although committed to charitable works, New York’s philanthropic pioneers did not trust charity alone to bring lasting improvements in the lives of the urban poor. Their assumption—increasingly common among the mercantile and professional classes, successful artisan-entrepreneurs, and well-off mechanics alike—was that poverty stemmed from moral turpitude, not merely, or even mainly, from misfortune. With the breakdown of traditional relations of production, households and workshops could no longer be relied upon to teach the habits of self-discipline and self-reliance necessary for survival in a wage-labor economy. Prudence, decency, sobriety, thrift, punctuality—these and similar virtues would now, more than ever, have to be instilled through what Pintard described as “the slow process of education & religious instruction.”

Ample precedents already existed, in fact, for using schools to provide poor children with the kind of guidance once supplied by households and workshops. By the mid-1790s there were half a dozen so-called “charity schools” in town, plus a dozen-odd “pay schools” run by free-lance masters. Together, they enrolled better than half the children in the city between the ages of five and fifteen—girls as well as boys, blacks as well as whites, representing a broad cross-section of social classes. Additional charity schools sprang up around the turn of the century, including one organized by Isabella Graham’s Society for the Relief of Poor Widows. The Female Association, founded in 1798, opened a school to teach poor girls the “principles of piety and virtue.”

In 1806 Mrs. Graham and her daughter, Joanna Bethune (wife of wealthy reformer Divie Bethune), conceived the idea of founding an orphanage where working-class children could be brought up to lead productive lives. Orphanages were unknown in the United States—New Amsterdam’s short-lived orphan asylum was now a dim memory at best—but they had been strongly endorsed by European reformers. When Graham and Bethune unveiled their idea before a meeting of prominent ladies at the City Hotel (one of those in attendance was Elizabeth Hamilton, Alexander’s widow), it won enthusiastic approval and led at once to the formation of the Orphan Asylum Society. In 1807 the cornerstone of its first home was laid at the corner of Barrow and Asylum (now 4th) streets in Greenwich. (Nearby Bethune Street commemorates Joanna Bethune’s long career as a philanthropist and educator.)

It seemed doubtful, though, that these scattered, uncoordinated initiatives could bring about major improvements in the manners and morals of the poor. Thomas Eddy, the wealthy Quaker who served as almshouse commissioner and warden of Newgate, raised this problem in his correspondence with Patrick Colquhoun, a London police magistrate active in the famed British Society for Bettering the Condition of the Poor. In 1803 Colquhoun warned Eddy that if American schools weren’t soon put on more solid foundations, the country’s rapidly expanding population would cause a crisis “manifested by extreme ignorance and immoral conduct, as it respects a considerable proportion of the lower classes of society.”

That was enough for Eddy. With the help of Pintard, Golden, Mitchill, Clinton, and other influential friends— and with financial assistance from the Masons—he set about organizing the New York Free School Society (1805). Its purpose, in Pintard’s phrase, was to eradicate crime and pauperism in the city by inculcating “habits of cleanliness, subordination, and order” in the children of the lower classes.

To that end, its first school, which opened the following year in rented quarters in the Fourth Ward, adopted the Lancasterian system of instruction. Devised by the English Quaker Joseph Lancaster, this involved the selection of older and better pupils as “monitors,” or assistant teachers, who were trained to drill information and biblical precepts into their younger charges. The system was cheap and efficient. To speed the morning roll call, pupils were each assigned a number that was posted on the wall against which they lined up, allowing monitors to see at once who was absent. Learning meant rote memorization, imagination was actively discouraged, and while Lancaster prohibited corporal punishment, pupils in need of additional motivation could be shackled to their desks or made to carry six-pound logs on their shoulders.

Pintard had said that the eradication of poverty required religious instruction as well as education, and here too he and other Manhattan reformers took their cues from abroad. William Wilberforce’s Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians (1797), widely reprinted in the United States, urged the responsible classes to spread Christian virtue among their social inferiors via bipartisan, nonsectarian organizations like his own Society for the Suppression of Vice. During the later 1790s and early 1800s, in accordance with this and similar recommendations, New York clergymen and lay leaders assembled an arsenal of specialized associations for moral uplift and humanitarian reform.

In 1794 John Stanford, an English Baptist who had migrated to the city in 1789, helped establish the New York Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge and Piety Among the Poor. Stanford had no regular pulpit in Manhattan, but he conducted a private school, instructed theological students, wrote and distributed religious tracts, and preached frequently around the city. Now his New York Society took up the task of distributing Bibles and religious pamphlets to the poor.

In 1796 the Dutch Reformed and Baptist churches jointly established the New York Missionary Society, which initially targeted Long Island Indians and published the Theological Magazine (1796-99). There was no mistaking the aims of the Society for Aiding and Assisting the Magistrates in the Suppression of Vice and Immorality on the Lord’s Day (1795), of the Society for the Suppression of Vice (1802), of the Society for the Suppression of Vice and Immorality (1810), or of such periodicals as the short-lived New-York Missionary Magazine and Repository (1800-1801), which ran articles demonstrating the divinity of Jesus, the coherence of the Bible, and the like. Hamilton’s Christian Constitutional Society (1802)—an attempt to tap this impulse on behalf of the Federalist party—went nowhere, as direct political intervention breached the separation of church and state, already a sacrosanct element of American republican thought.

Another British import, the Sunday school, reached New York in 1792, when Isabella Graham founded an evening Sunday school for adults, black as well as white, on Mulberry Street. The following year a former slave named Catherine Ferguson opened a Sunday school for both children and adults: Katy Ferguson’s School for the Poor in New York City. After 1800 the Sunday school movement in New York accelerated dramatically. In 1803 Graham, her daughter Joanna Bethune, and her son-in-law Divie Bethune—the Bethunes too were in regular contact with British reformers and followed closely the work of the London Sunday School Society—started a new Sunday school on Mott Street. Using the Bible as a textbook, the school offered reading and writing classes along with religious instruction. A decade later there were fifty Sunday schools in New York with a combined enrollment of six thousand.

As the campaign for popular religious instruction gained momentum, evangelical Protestant clergymen began to preach among the poor (more and more of them immigrant Catholics) confined in municipal institutions. The Rev. John Stanford became the semiofficial chaplain to the almshouse in 1807. He was soon preaching to the inmates of the hospital, debtors’ prison, insane asylum, and penitentiary as well, and in 1810 was joined by Ezra Stiles Ely, a young Presbyterian minister. Stanford and Ely published such shocking details about the physical and moral condition of their charges that Divie Bethune and other prominent reformers resolved to support their work with yet another organization, the interdominational Society for Supporting the Gospel Among the Poor of the City of New-York (1812). Both Stanford and Ely were named New York’s first municipal missionaries. For a score more years, Stanford in particular would maintain a herculean schedule of ministerial rounds, reporting annually on his sermons and the number of deathbed conversions among the paupers.

Never before in the city’s history had its upper classes gone to such lengths to rescue the souls and bodies of working and impoverished folk, or to educate their children. To Senator-Doctor-Professor Samuel Latham Mitchill—Friendly Club alumnus, Freemason in good standing, cofounder of the New-York Historical Society, the New-York Society for the Promotion of Agriculture, Arts, and Manufactures, and the New-York Free School Society—the time had therefore come to spread the good news that New York was no longer solely a center of commerce but one of culture and benevolence too. In 1807, accordingly, he published a pocket-sized volume entitled The Picture of New-York; or The Traveller’s Guide, Through the Commercial Metropolis of the United States, By a Gentleman Residing in this City.

Basically the city’s first guidebook, Mitchill’s Picture of New-York assailed the dearth of knowledge about this “great and growing capital” (even among its own residents) and denounced writers like Jedediah Morse, whose often-reprinted American Geography (1784) had ridiculed New York for its artistic, literary, and scientific backwardness. To set the record straight, Mitchill diligently compiled evidence of the city’s breathtaking growth over the previous twenty-odd years: the multiplication of banks and insurance companies, the upsurge in overseas and domestic commerce, the expansion of municipal services. What made him proudest, however, were the signs of New York’s cultural maturity. Its numerous newspapers, booksellers, reading rooms, theaters, parks, medical and scientific organizations, literary societies, and the new apparatus of reform and benevolence—all of these now put the city far ahead of erstwhile rivals like Boston or Philadelphia. For the men and women of his class who envisioned New York as something more than an island of benighted shopkeepers, this was praise indeed.